6.6: Byzantine

- Page ID

- 67079

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Byzantine art

The Roman Empire continued as the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople.

c. 330 - 1453 C.E.

A beginner's guide

Byzantine art, an introduction

To speak of “Byzantine Art” is a bit problematic, since the Byzantine empire and its art spanned more than a millennium and penetrated geographic regions far from its capital in Constantinople. Thus, Byzantine art includes work created from the fourth century to the fifteenth century and encompassing parts of the Italian peninsula, the eastern edge of the Slavic world, the Middle East, and North Africa. So what is Byzantine art, and what do we mean when we use this term?

It’s helpful to know that Byzantine art is generally divided up into three distinct periods:

Early Byzantine (c. 330–843)

Middle Byzantine (c. 843–1204)

Late Byzantine (c. 1261–1453)

Early Byzantine (c. 330–750)

The Emperor Constantine adopted Christianity and in 330 moved his capital from Rome to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), at the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. Christianity flourished and gradually supplanted the Greco-Roman gods that had once defined Roman religion and culture. This religious shift dramatically affected the art that was created across the empire.

The earliest Christian churches were built during this period, including the famed Hagia Sophia (above), which was built in the sixth century under Emperor Justinian. Decorations for the interior of churches, including icons and mosaics, were also made during this period. Icons, such as the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (left), served as tools for the faithful to access the spiritual world—they served as spiritual gateways.

Similarly, mosaics, such as those within the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, sought to evoke the heavenly realm. In this work, ethereal figures seem to float against a gold background that is representative of no identifiable earthly space. By placing these figures in a spiritual world, the mosaics gave worshipers some access to that world as well. At the same time, there are real-world political messages affirming the power of the rulers in these mosaics. In this sense, art of the Byzantine Empire continued some of the traditions of Roman art.

Generally speaking, Byzantine art differs from the art of the Romans in that it is interested in depicting that which we cannot see—the intangible world of Heaven and the spiritual. Thus, the Greco-Roman interest in depth and naturalism is replaced by an interest in flatness and mystery.

Middle Byzantine (c. 850–1204)

The Middle Byzantine period followed a period of crisis for the arts called the Iconoclastic Controversy, when the use of religious images was hotly contested. Iconoclasts (those who worried that the use of images was idolatrous), destroyed images, leaving few surviving images from the Early Byzantine period. Fortunately for art history, those in favor of images won the fight and hundreds of years of Byzantine artistic production followed.

The stylistic and thematic interests of the Early Byzantine period continued during the Middle Byzantine period, with a focus on building churches and decorating their interiors. There were some significant changes in the empire, however, that brought about some change in the arts. First, the influence of the empire spread into the Slavic world with the Russian adoption of Orthodox Christianity in the tenth century. Byzantine art was therefore given new life in the Slavic lands.

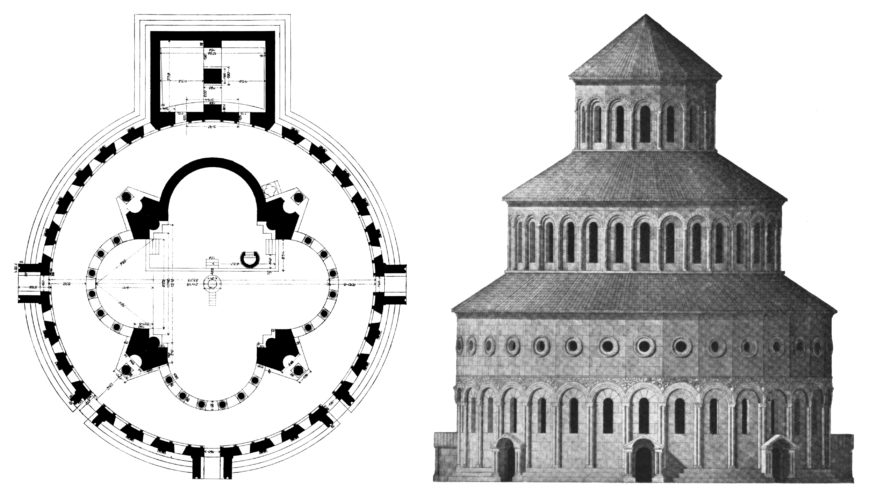

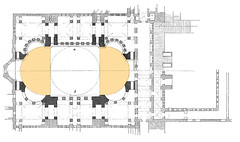

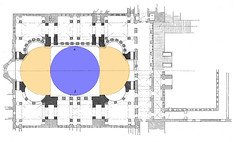

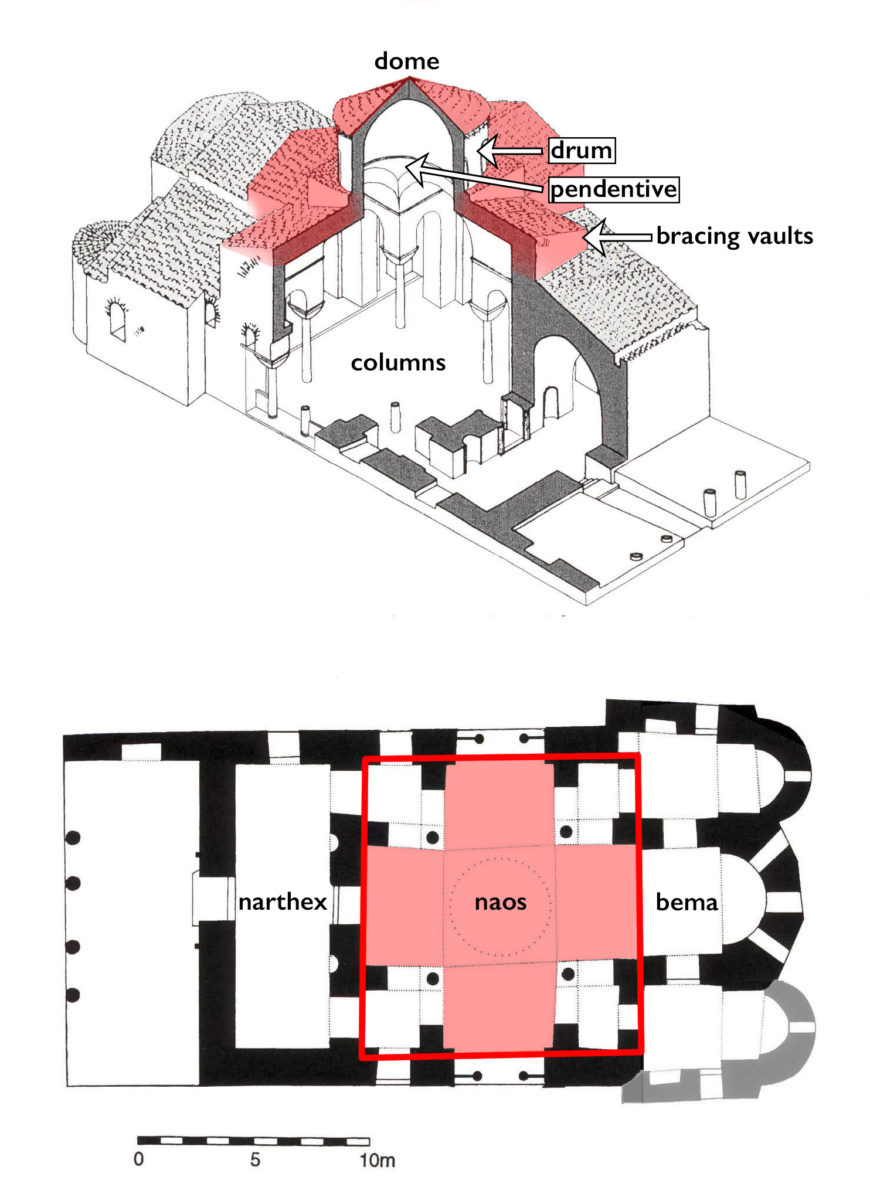

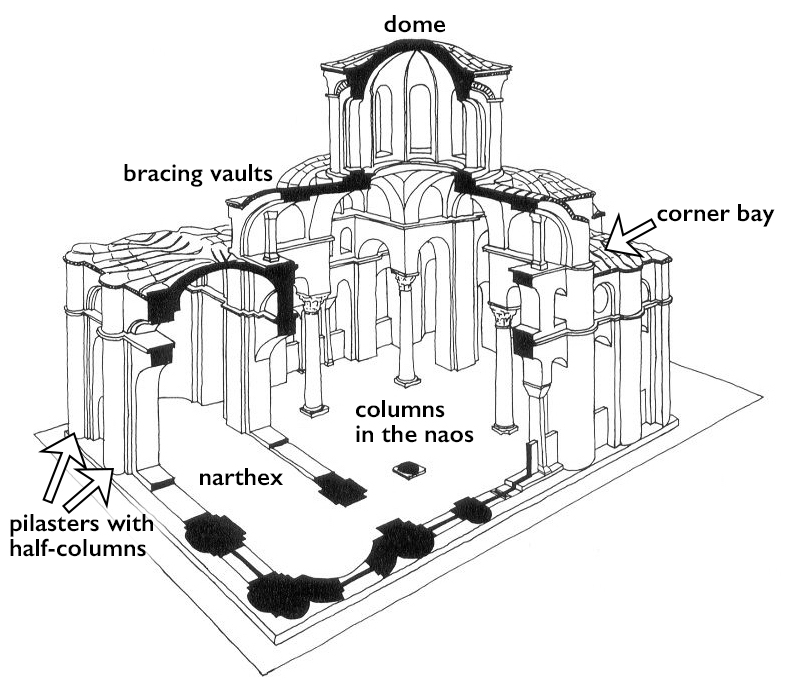

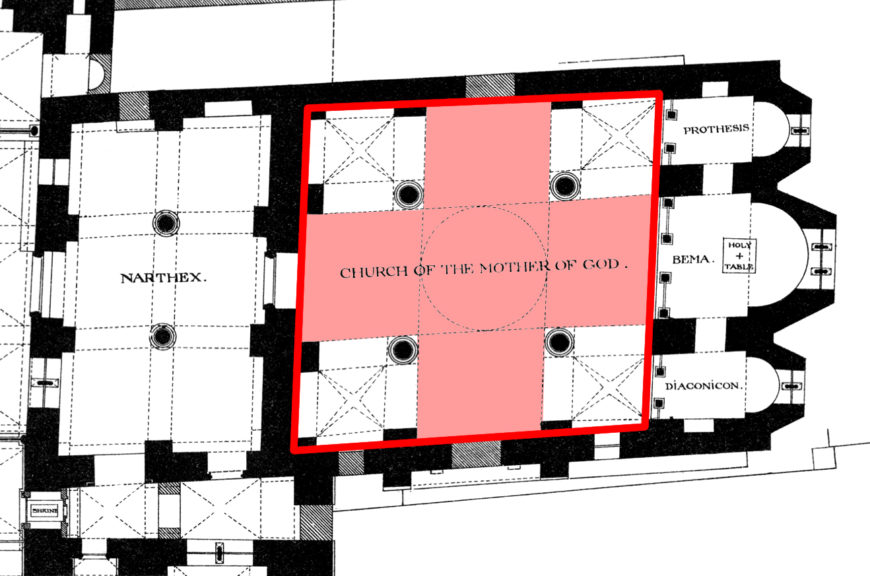

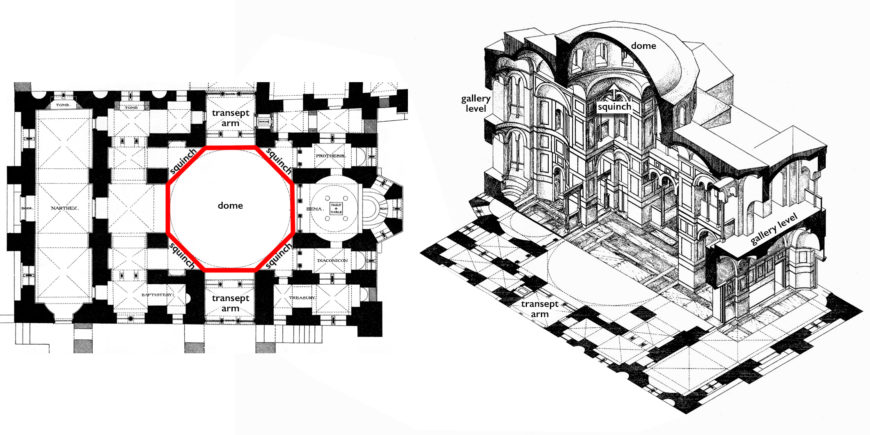

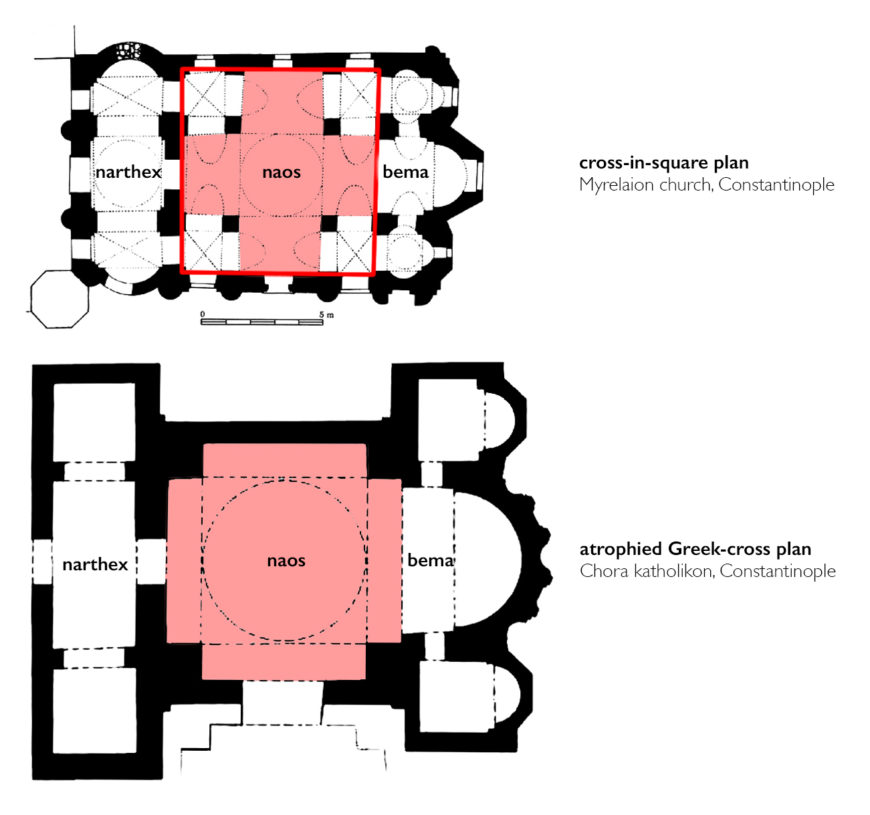

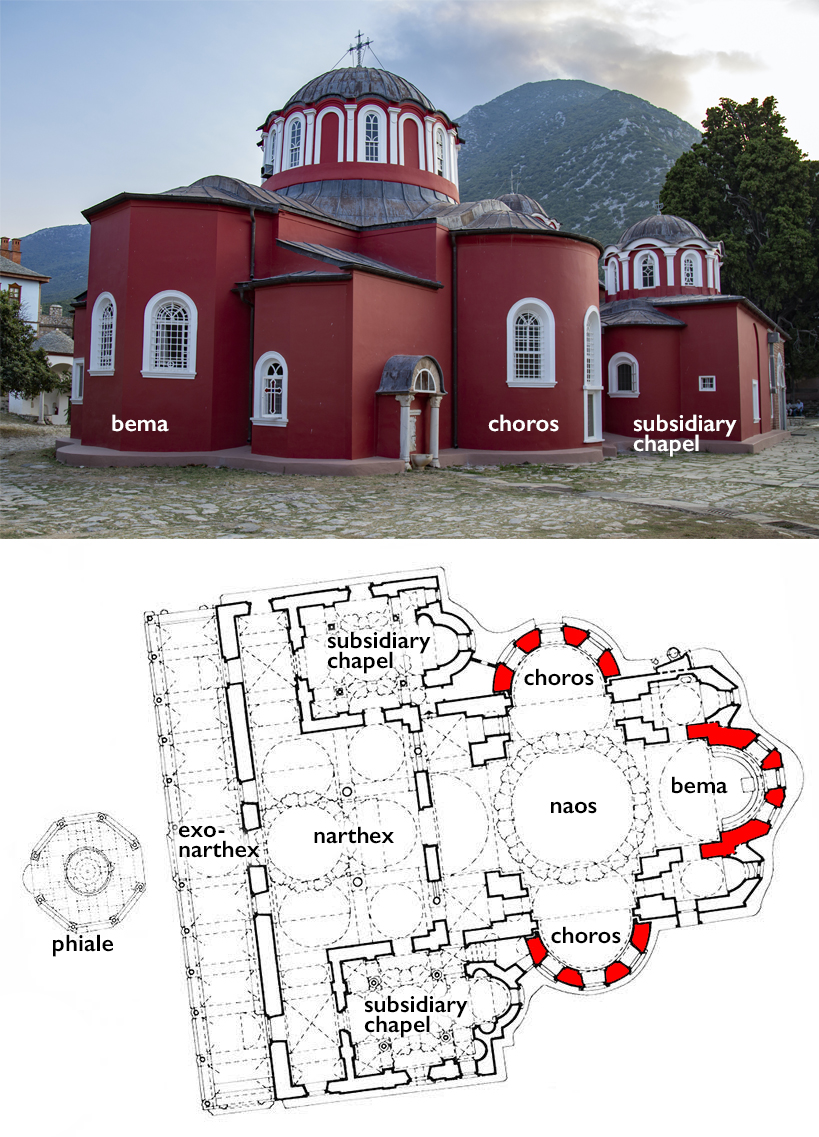

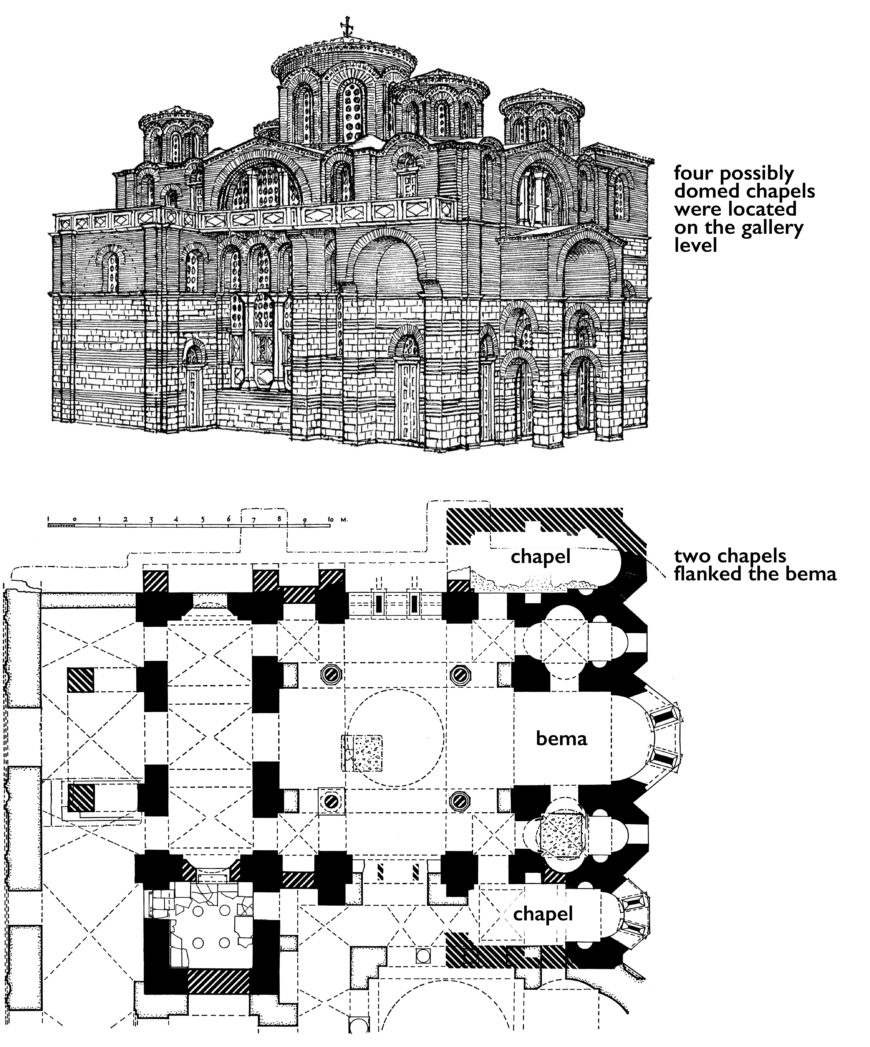

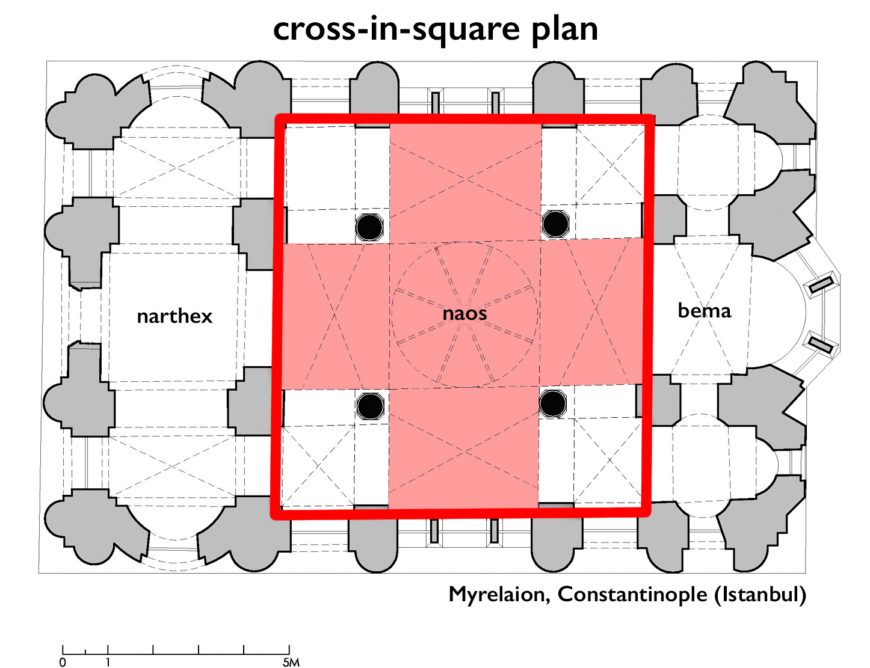

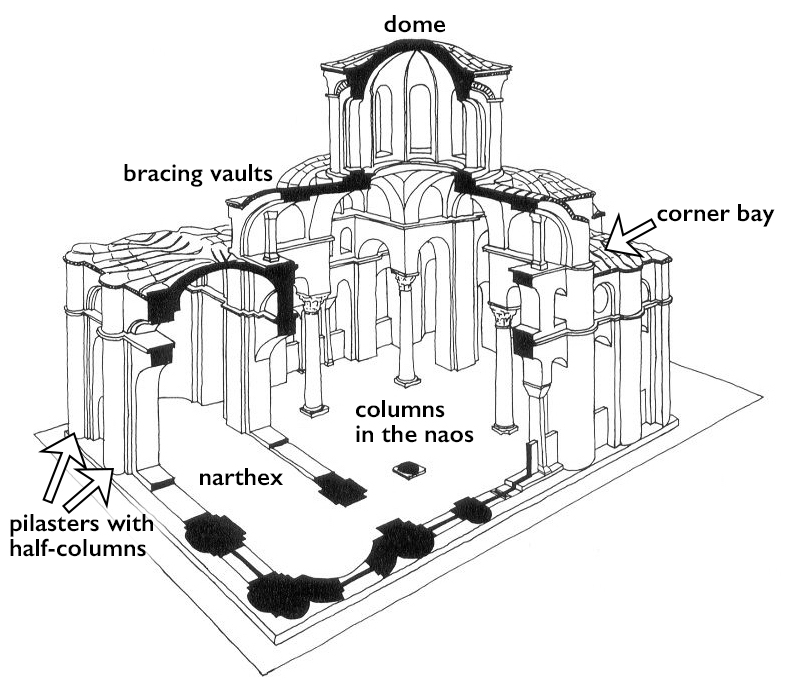

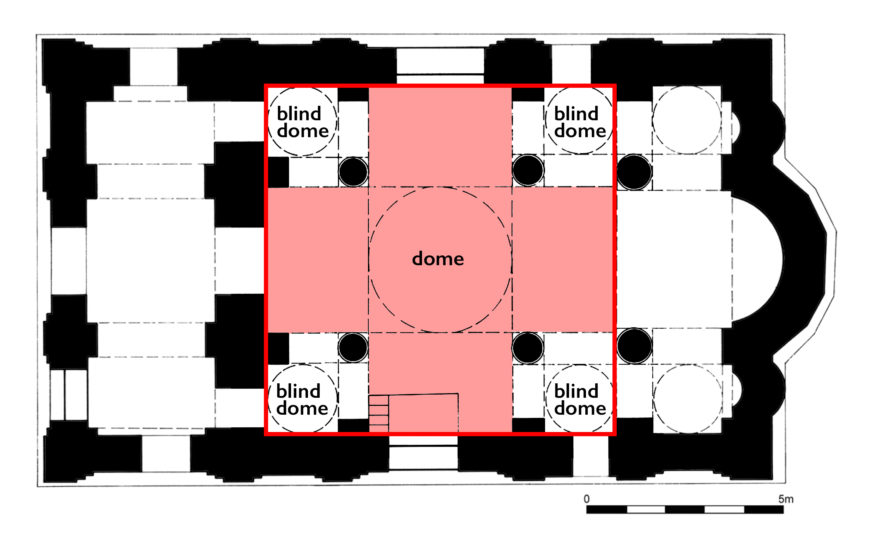

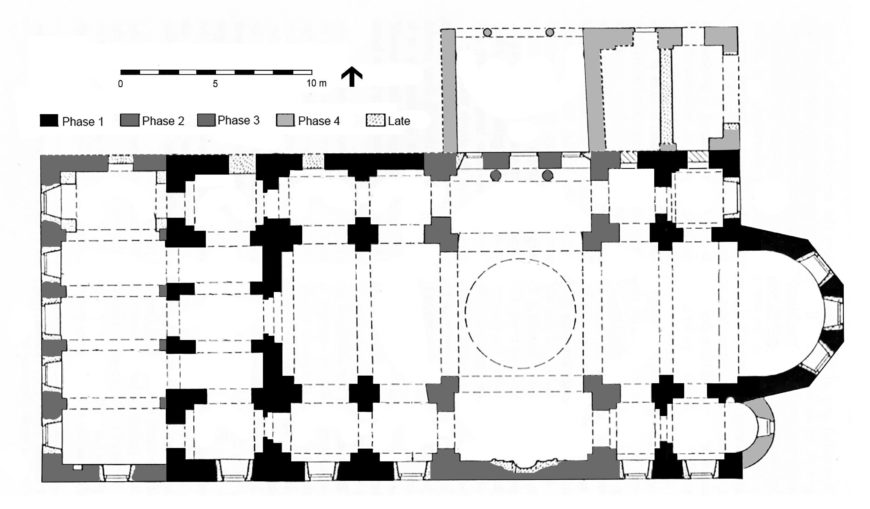

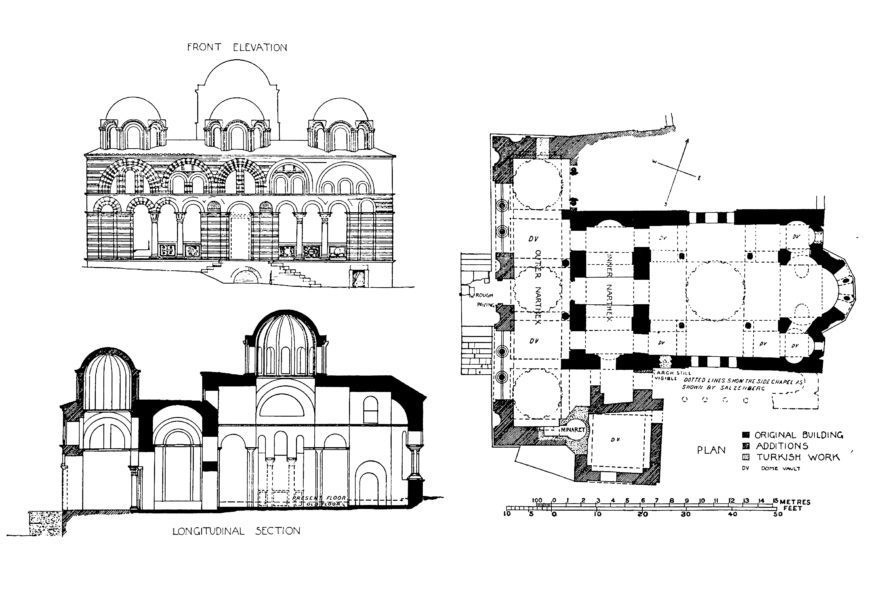

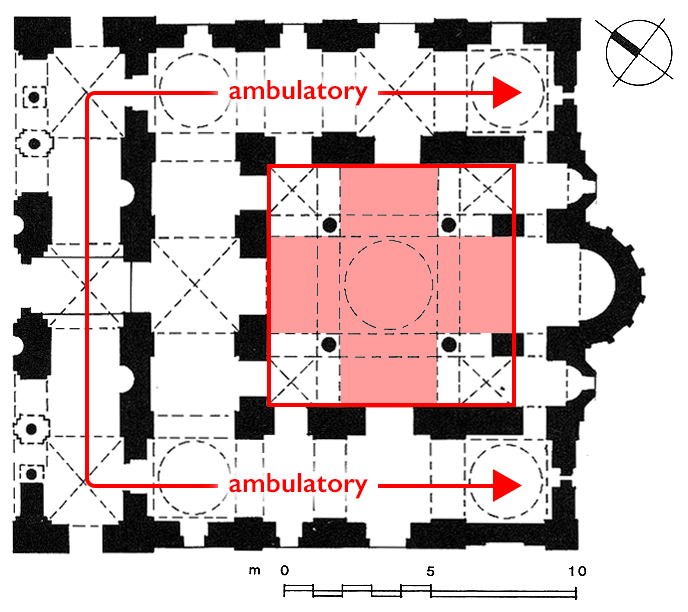

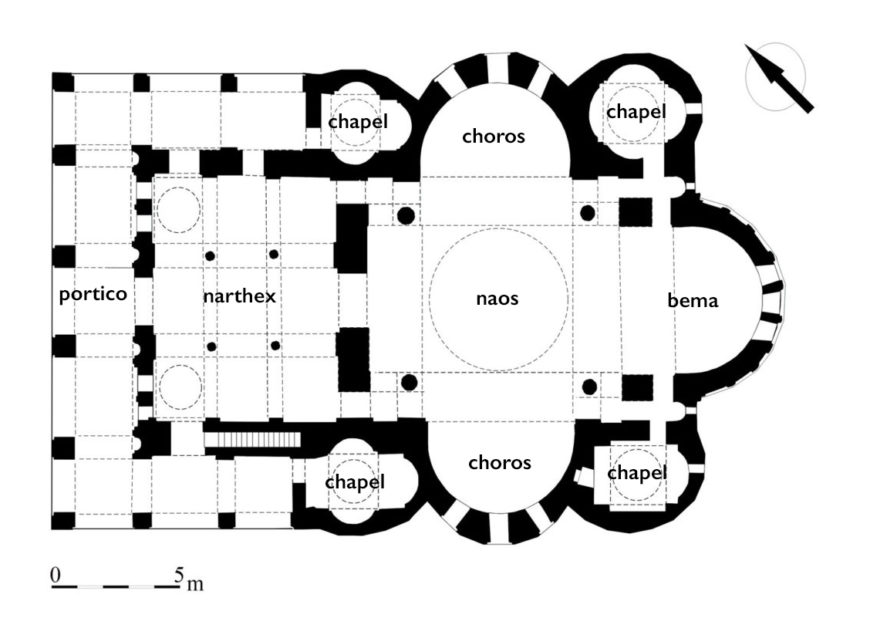

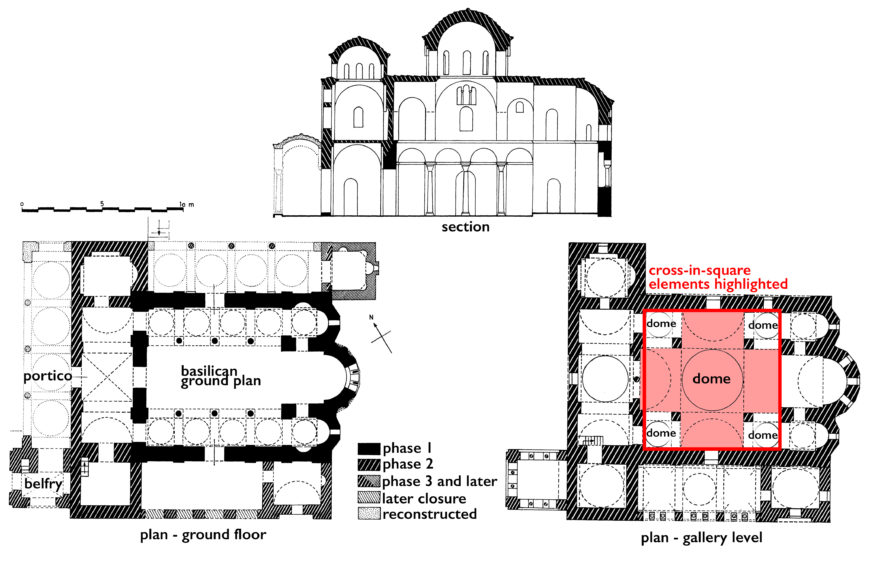

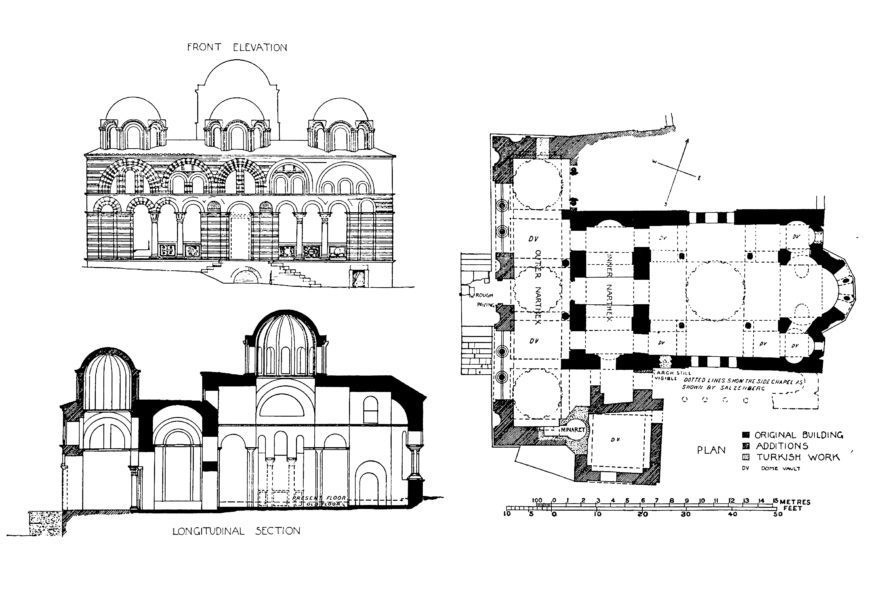

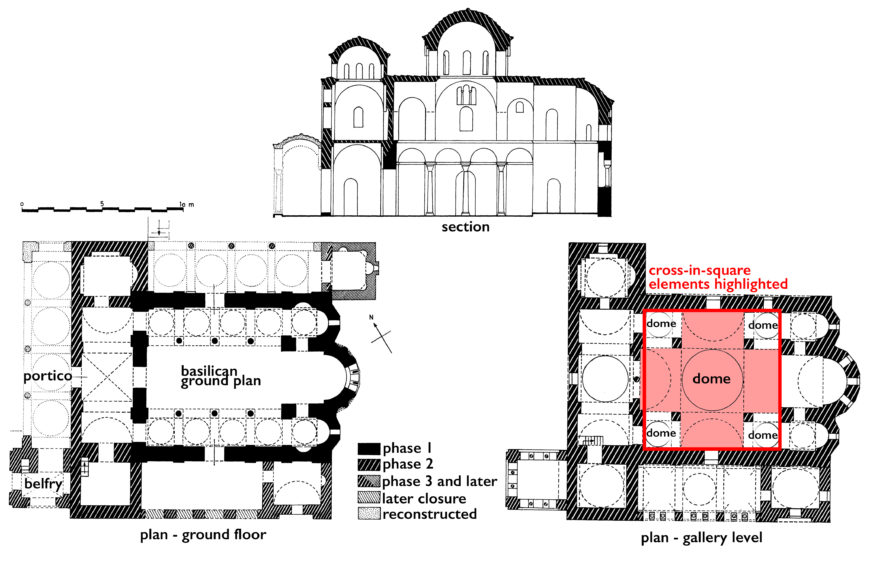

Architecture in the Middle Byzantine period overwhelmingly moved toward the centralized cross-in-square plan for which Byzantine architecture is best known.

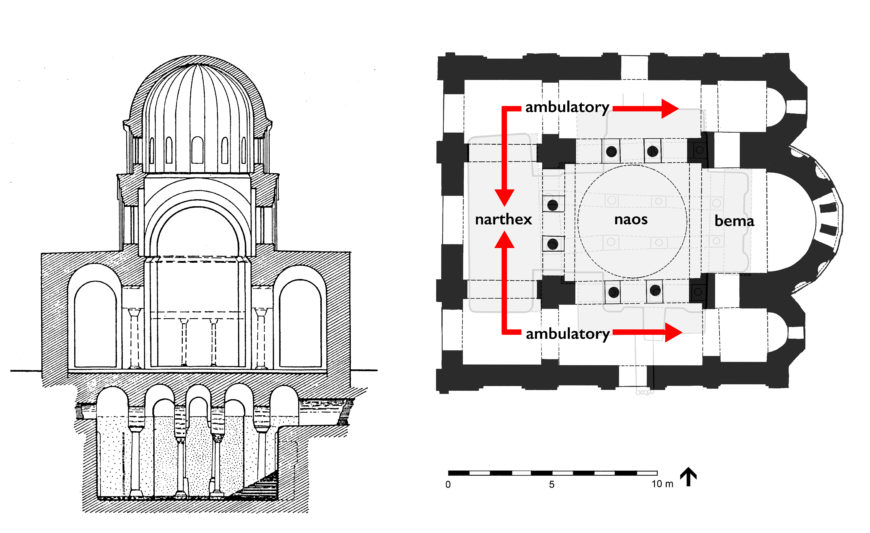

These churches were usually on a much smaller-scale than the massive Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, but, like Hagia Sophia, the roofline of these churches was always defined by a dome or domes. This period also saw increased ornamentation on church exteriors. A particularly good example of this is the tenth-century Hosios Loukas Monastery in Greece (above).

This was also a period of increased stability and wealth. As such, wealthy patrons commissioned private luxury items, including carved ivories, such as the celebrated Harbaville Tryptich (above and below), which was used as a private devotional object. Like the sixth-century icon discussed above (Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George), it helped the viewer gain access to the heavenly realm. Interestingly, the heritage of the Greco-Roman world can be seen here, in the awareness of mass and space. See for example the subtle breaking of the straight fall of drapery by the right knee that projects forward in the two figures in the bottom register of the Harbaville Triptych (left). This interest in representing the body with some naturalism is reflective of a revived interest in the classical past during this period. So, as much as it is tempting to describe all Byzantine art as “ethereal” or “flattened,” it is more accurate to say that Byzantine art is diverse. There were many political and religious interests as well as distinct cultural forces that shaped the art of different periods and regions within the Byzantine Empire.

Late Byzantine (c. 1261– 1453)

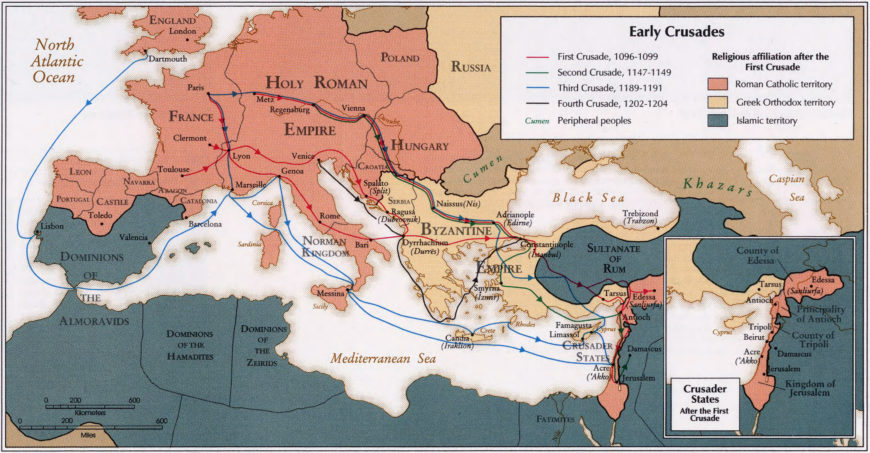

Between 1204 and 1261, the Byzantine Empire suffered another crisis: the Latin Occupation. Crusaders from Western Europe invaded and captured Constantinople in 1204, temporarily toppling the empire in an attempt to bring the eastern empire back into the fold of western Christendom. (By this point Christianity had divided into two distinct camps: eastern [Orthodox] Christianity in the Byzantine Empire and western [Latin] Christianity in the European west.)

By 1261 the Byzantine Empire was free of its western occupiers and stood as an independent empire once again, albeit markedly weakened. The breadth of the empire had shrunk, and so had its power. Nevertheless Byzantium survived until the Ottomans took Constantinople in 1453. In spite of this period of diminished wealth and stability, the arts continued to flourish in the Late Byzantine period, much as it had before.

Although Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453—bringing about the end of the Byzantine Empire—Byzantine art and culture continued to live on in its far-reaching outposts, as well as in Greece, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire, where it had flourished for so long. The Russian Empire, which was first starting to emerge around the time Constantinople fell, carried on as the heir of Byzantium, with churches and icons created in a distinct “Russo-Byzantine” style (left). Similarly, in Italy, when the Renaissance was first emerging, it borrowed heavily from the traditions of Byzantium. Cimabue’s Madonna Enthroned of 1280–1290 is one of the earliest examples of the Renaissance interest in space and depth in panel painting. But the painting relies on Byzantine conventions and is altogether indebted to the arts of Byzantium.

So, while we can talk of the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, it is much more difficult to draw geographic or temporal boundaries around the empire, for it spread out to neighboring regions and persisted in artistic traditions long after its own demise.

Additional resources:

Harbaville Triptych at the Louvre

Byzantium on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

For instructors: related lesson plan on Art History Teaching Resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

About the chronological periods of the Byzantine Empire

This essay is intended to introduce the periods of Byzantine history, with attention to developments in art and architecture.

From Rome to Constantinople

In 313, the Roman Empire legalized Christianity, beginning a process that would eventually dismantle its centuries-old pagan tradition. Not long after, emperor Constantine transferred the empire’s capital from Rome to the ancient Greek city of Byzantion (modern Istanbul). Constantine renamed the new capital city “Constantinople” (“the city of Constantine”) after himself and dedicated it in the year 330. With these events, the Byzantine Empire was born—or was it?

The term “Byzantine Empire” is a bit of a misnomer. The Byzantines understood their empire to be a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire and referred to themselves as “Romans.” The use of the term “Byzantine” only became widespread in Europe after Constantinople finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. For this reason, some scholars refer to Byzantium as the “Eastern Roman Empire.”

Byzantine History

The history of Byzantium is remarkably long. If we reckon the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from the dedication of Constantinople in 330 until its fall to the Ottomans in 1453, the empire endured for some 1,123 years.

Scholars typically divide Byzantine history into three major periods: Early Byzantium, Middle Byzantium, and Late Byzantium. But it is important to note that these historical designations are the invention of modern scholars rather than the Byzantines themselves. Nevertheless, these periods can be helpful for marking significant events, contextualizing art and architecture, and understanding larger cultural trends in Byzantium’s history.

Early Byzantium: c. 330–843

Scholars often disagree about the parameters of the Early Byzantine period. On the one hand, this period saw a continuation of Roman society and culture—so, is it really correct to say it began in 330? On the other, the empire’s acceptance of Christianity and geographical shift to the east inaugurated a new era.

Following Constantine’s embrace of Christianity, the church enjoyed imperial patronage, constructing monumental churches in centers such as Rome, Constantinople, and Jerusalem. In the west, the empire faced numerous attacks by Germanic nomads from the north, and Rome was sacked by the Goths in 410 and by the Vandals in 455. The city of Ravenna in northeastern Italy rose to prominence in the 5th and 6th centuries when it functioned as an imperial capital for the western half of the empire. Several churches adorned with opulent mosaics, such as San Vitale and the nearby Sant’Apollinare in Classe, testify to the importance of Ravenna during this time.

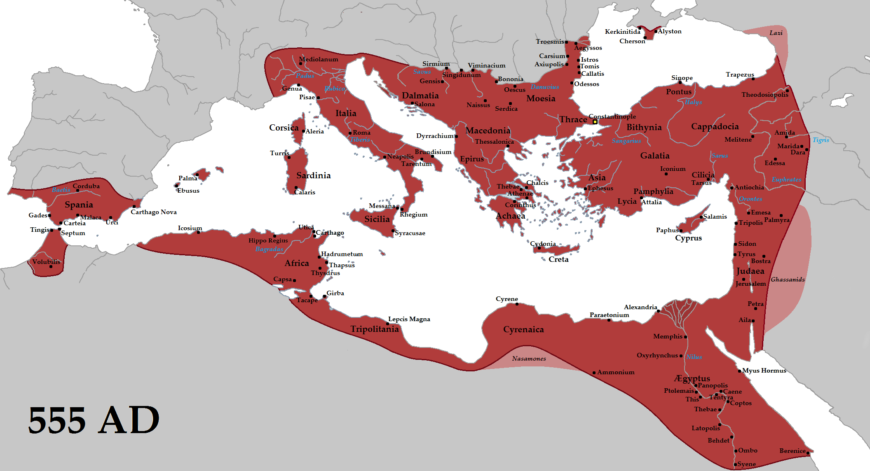

Under the sixth-century emperor Justinian I, who reigned 527–565, the Byzantine Empire expanded to its largest geographical area: encompassing the Balkans to the north, Egypt and other parts of north Africa to the south, Anatolia (what is now Turkey) and the Levant (including including modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan) to the east, and Italy and the southern Iberian Peninsula (now Spain and Portugal) to the west. Many of Byzantium’s greatest architectural monuments, such as the innovative domed basilica of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, were also built during Justinian’s reign.

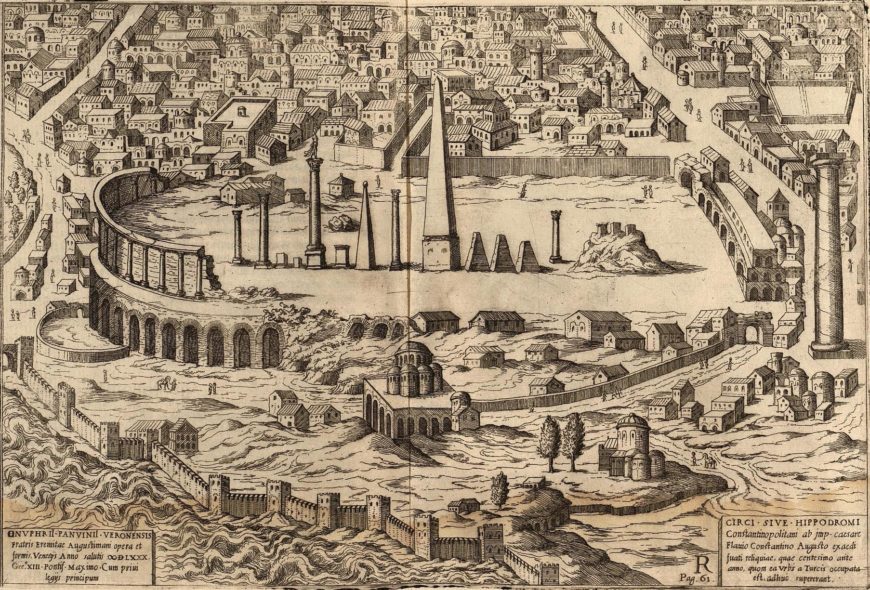

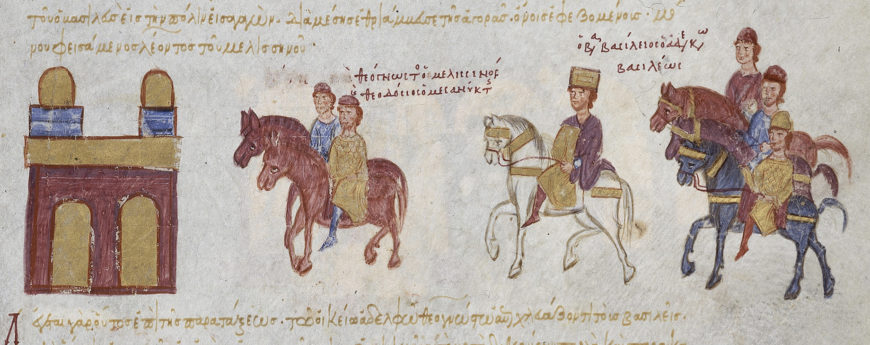

Following the example of Rome, Constantinople featured a number of outdoor public spaces—including major streets, fora, as well as a hippodrome (a course for horse or chariot racing with public seating)—in which emperors and church officials often participated in showy public ceremonies such as processions.

Christian monasticism, which began to thrive in the 4th century, received imperial patronage at sites like Mount Sinai in Egypt.

Yet the mid-7th century began what some scholars call the “dark ages” or the “transitional period” in Byzantine history. Following the rise of Islam in Arabia and subsequent attacks by Arab invaders, Byzantium lost substantial territories, including Syria and Egypt, as well as the symbolically important city of Jerusalem with its sacred pilgrimage sites. The empire experienced a decline in trade and an economic downturn.

Against this backdrop, and perhaps fueled by anxieties about the fate of the empire, the so-called “Iconoclastic Controversy” erupted in Constantinople in the 8th and 9th centuries. Church leaders and emperors debated the use of religious images that depicted Christ and the saints, some honoring them as holy images, or “icons,” and others condemning them as idols (like the images of deities in ancient Rome) and apparently destroying some. Finally, in 843, Church and imperial authorities definitively affirmed the use of religious images and ended the Iconoclastic Controversy, an event subsequently celebrated by the Byzantines as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.”

Middle Byzantium: c. 843–1204

In the period following Iconoclasm, the Byzantine empire enjoyed a growing economy and reclaimed some of the territories it lost earlier. With the affirmation of images in 843, art and architecture once again flourished. But Byzantine culture also underwent several changes.

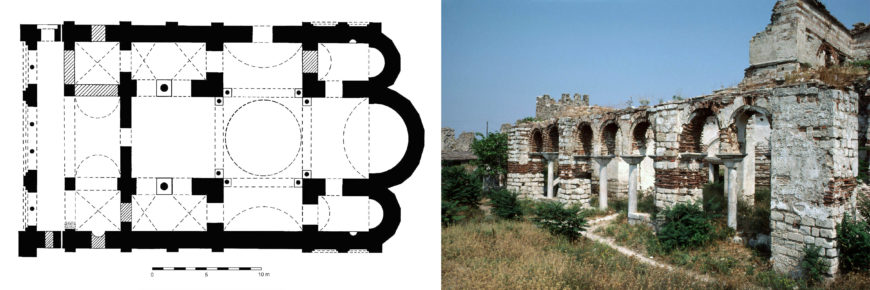

Middle Byzantine churches elaborated on the innovations of Justinian’s reign, but were often constructed by private patrons and tended to be smaller than the large imperial monuments of Early Byzantium. The smaller scale of Middle Byzantine churches also coincided with a reduction of large, public ceremonies.

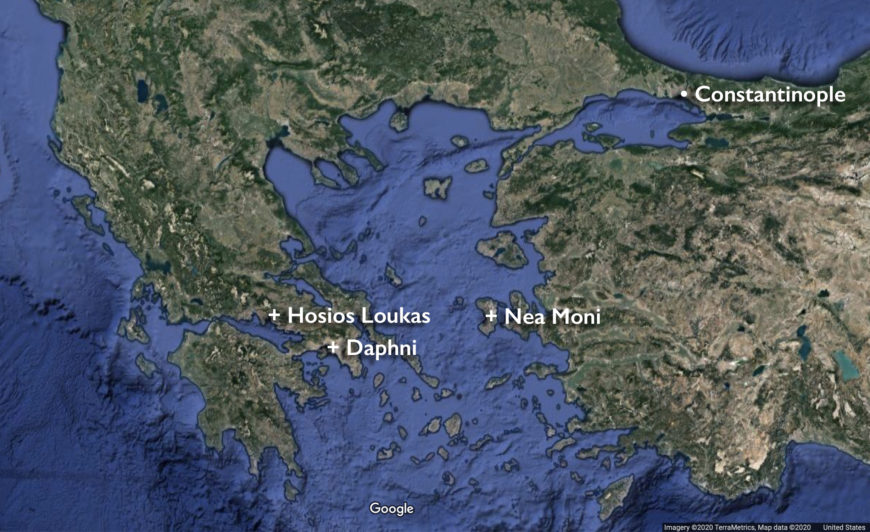

Monumental depictions of Christ and the Virgin, biblical events, and an array of various saints adorned church interiors, as seen in the sophisticated decorative programs at the monastery churches of Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni, and Daphni in Greece. But Middle Byzantine churches largely exclude depictions of the flora and fauna of the natural world that often appeared in Early Byzantine mosaics, perhaps in response to accusations of idolatry during the Iconoclastic Controversy. In addition to these developments in architecture and monumental art, exquisite examples of manuscripts, cloisonné enamels, stonework, and ivory carving survive from this period as well.

The Middle Byzantine period also saw increased tensions between the Byzantines and western Europeans (whom the Byzantines often referred to as “Latins” or “Franks”). The so-called “Great Schism” of 1054 signaled growing divisions between Orthodox Christians in Byzantium and Roman Catholics in western Europe.

The Fourth Crusade and the Latin Empire: 1204–1261

In 1204, the Fourth Crusade—undertaken by western Europeans loyal to the pope in Rome—veered from its path to Jerusalem and sacked the Christian city of Constantinople. Many of Constantinople’s artistic treasures were destroyed or carried back to western Europe as booty. The crusaders occupied Constantinople and established a “Latin Empire” in Byzantine territory. Exiled Byzantine leaders established three successor states: the Empire of Nicaea in northwestern Anatolia, the Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia, and the Despotate of Epirus in northwestern Greece and Albania. In 1261, the Empire of Nicaea retook Constantinople and crowned Michael VIII Palaiologos as emperor, establishing the Palaiologan dynasty that would reign until the end of the Byzantine Empire.

While the Fourth Crusade fueled animosity between eastern and western Christians, the crusades nevertheless encouraged cross-cultural exchange that is apparent in the arts of Byzantium and western Europe, and particularly in Italian paintings of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, exemplified by new depictions of St. Francis painted in the so-called Italo-Byzantine style.

Late Byzantium: 1261–1453

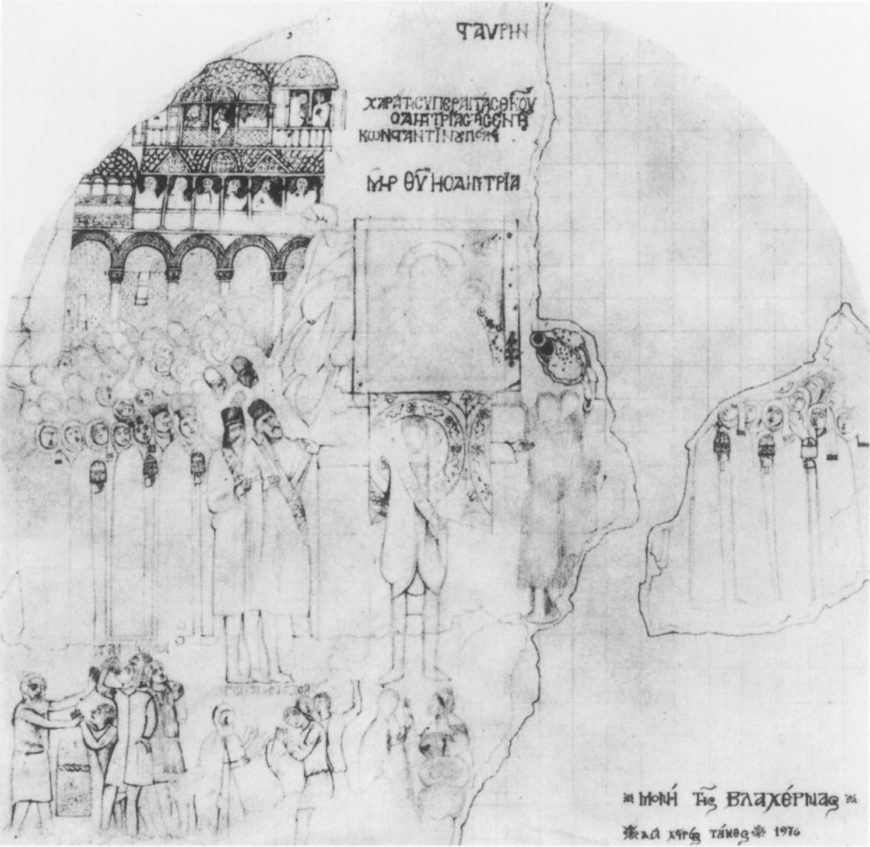

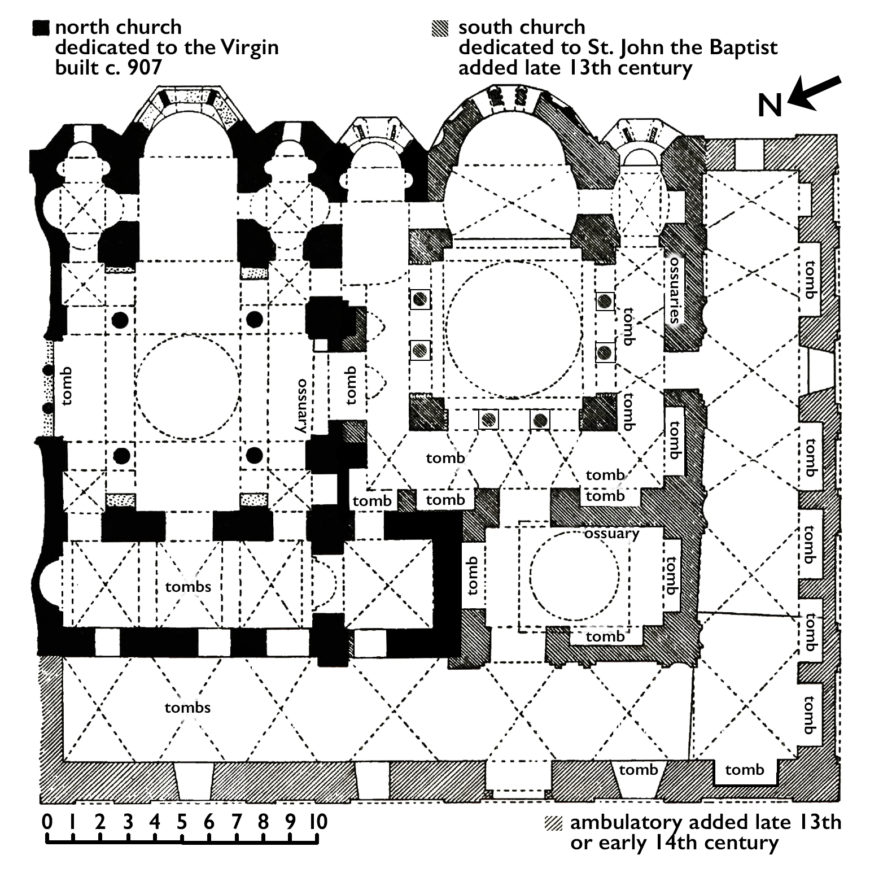

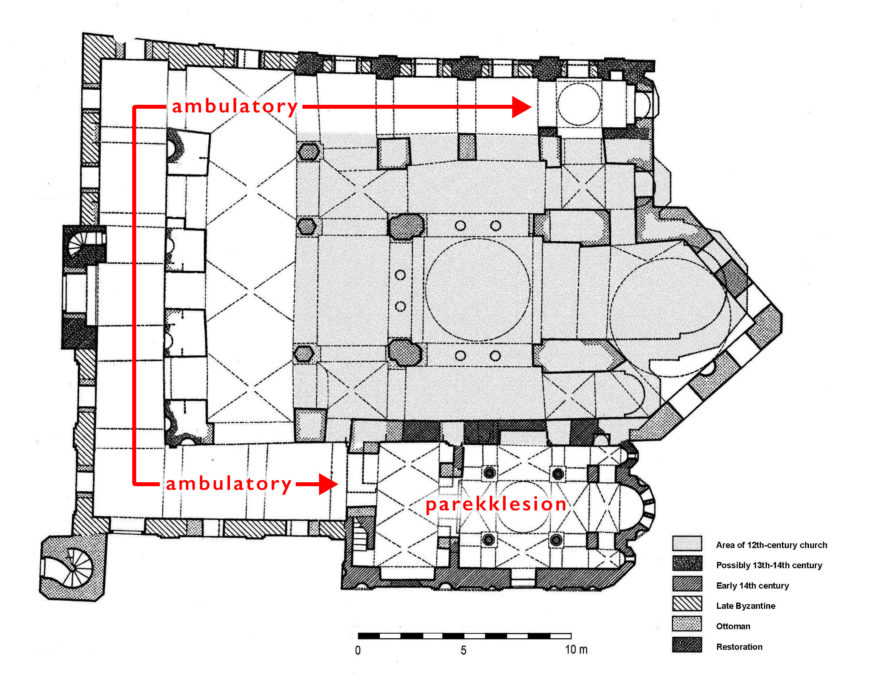

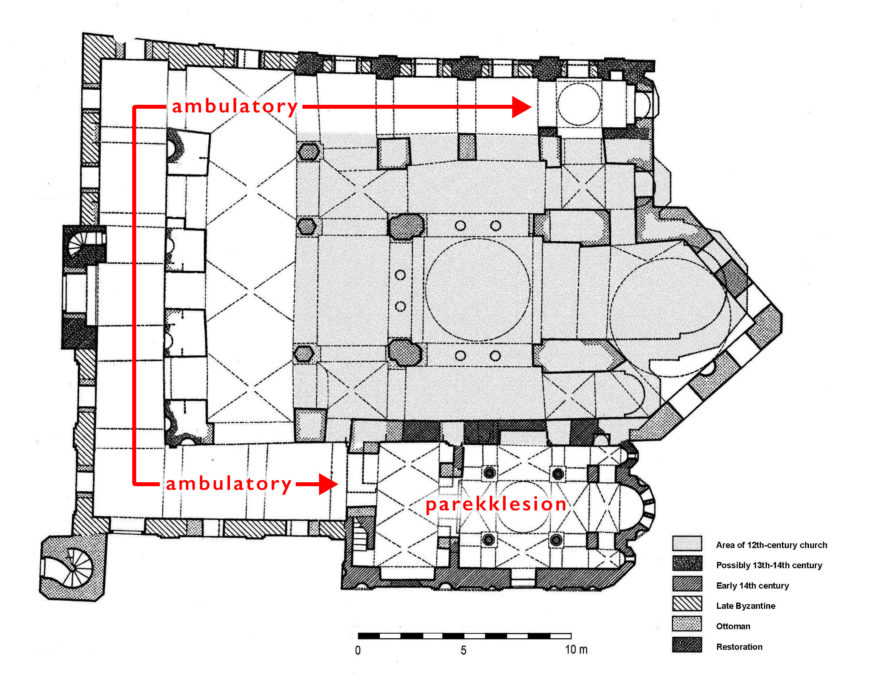

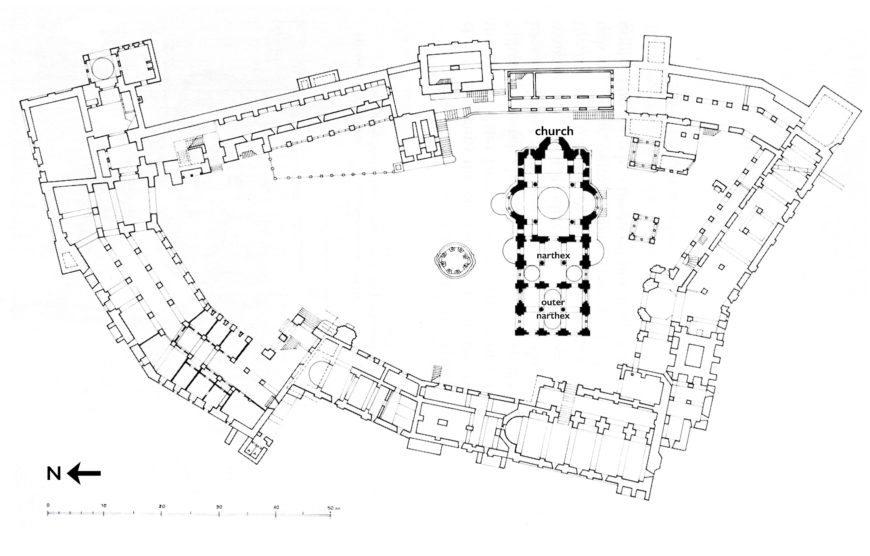

Artistic patronage again flourished after the Byzantines re-established their capital in 1261. Some scholars refer to this cultural flowering as the “Palaiologan Renaissance” (after the ruling Palaiologan dynasty). Several existing churches—such as the Chora Monastery in Constantinople—were renovated, expanded, and lavishly decorated with mosaics and frescos. Byzantine artists were also active outside Constantinople, both in Byzantine centers such as Thessaloniki, as well as in neighboring lands, such as the Kingdom of Serbia, where the signatures of the painters named Michael Astrapas and Eutychios have been preserved in frescos from the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

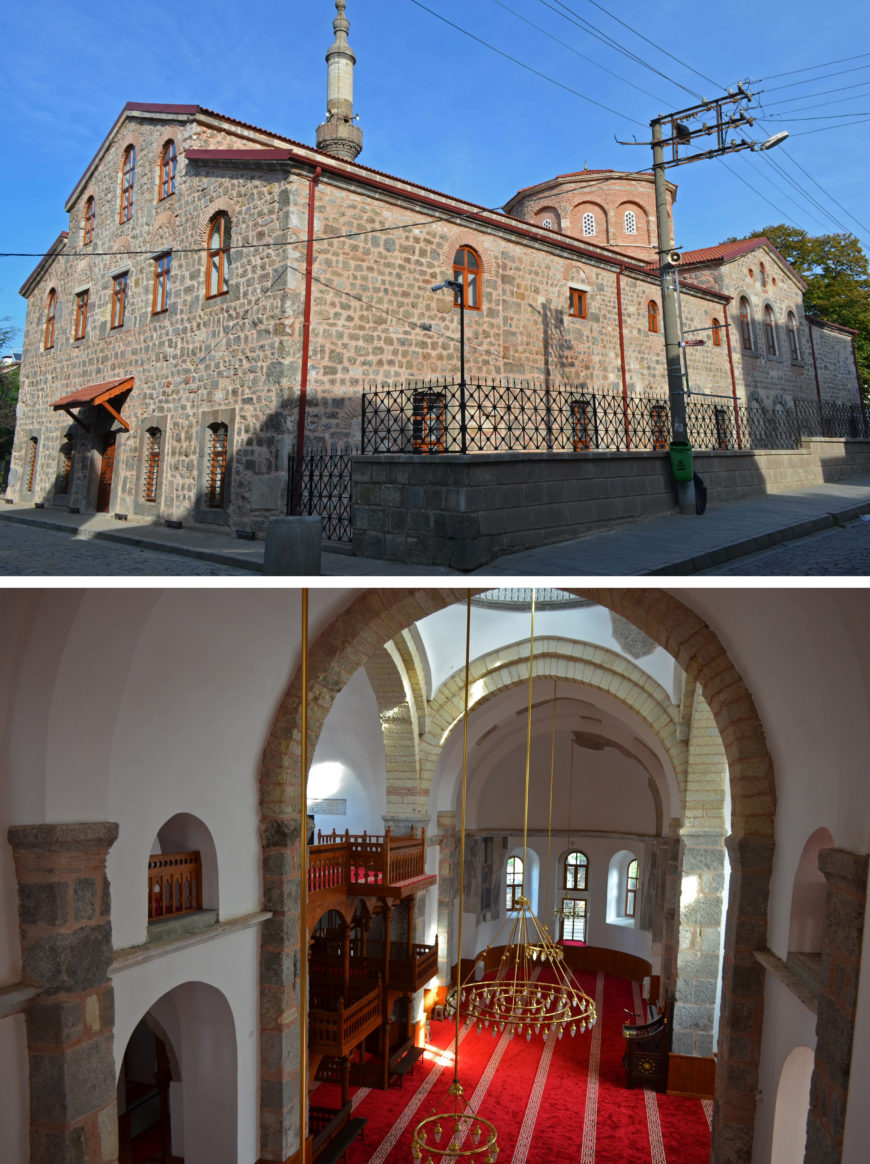

Yet the Byzantine Empire never fully recovered from the blow of the Fourth Crusade, and its territory continued to shrink. Byzantium’s calls for military aid from western Europeans in the face of the growing threat of the Ottoman Turks in the east remained unanswered. In 1453, the Ottomans finally conquered Constantinople, converting many of Byzantium’s great churches into mosques, and ending the long history of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Post-Byzantium: after 1453

Despite the ultimate demise of the Byzantine Empire, the legacy of Byzantium continued. This is evident in formerly Byzantine territories like Crete, where the so-called “Cretan School” of iconography flourished under Venetian rule (a famous product of the Cretan School being Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco).

But Byzantium’s influence also continued to spread beyond its former cultural and geographic boundaries, in the architecture of the Ottomans, the icons of Russia, the paintings of Italy, and elsewhere.

Additional Resources

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): “Byzantium (ca. 330–1453),” The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Iconoclastic controversies

The word “icon” refers to many different things today. For example, we use this word to refer to the small graphic symbols in our software and to powerful cultural figures. Nevertheless, these different meanings retain a connection to the word’s original meaning. “Icon” is Greek for “image” or “painting” and during the medieval era, this meant a religious image on a wooden panel used for prayer and devotion. More specifically, icons came to typify the art of the Orthodox Christian Church.

“Iconoclasm” refers to the destruction of images or hostility toward visual representations in general. More specifically, the word is used for the Iconoclastic Controversy that shook the Byzantine Empire for more than 100 years.

Open hostility toward religious representations began in 726 when Emperor Leo III publicly took a position against icons; this resulted in their removal from churches and their destruction. There had been many previous theological disputes over visual representations, their theological foundations and legitimacy. However, none of these caused the tremendous social, political and cultural upheaval of the Iconoclastic Controversy.

Some historians believe that by prohibiting icons, the Emperor sought to integrate Muslim and Jewish populations. Both Muslims and Jews perceived Christian images (that existed from the earliest times of Christianity) as idols and in direct opposition to the Old Testament prohibition of visual representations. The first commandment states,

You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself a carved image – any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, or that is in the waters under the earth. You shall not adore them, nor serve them (Exodus 20:3-5).

Another theory suggests that the prohibition was an attempt to restrain the growing wealth and power of the monasteries. They produced the icons and were a primary target of the violence of the Iconoclastic Controversy. Other scholars offer a less political motive, suggesting that the prohibition was primarily religious, an attempt to correct the wayward practice of worshiping images.

The trigger for Leo III’s prohibition may have even been the huge volcanic eruption in 726 in the Aegean Sea interpreted as a sign of God’s anger over the veneration of icons. There is no one simple answer to this complex event. What we do know is that the prohibition essentially caused a civil war which shook the political, social and religious spheres of the empire. The conflict pitted the emperor and certain high church officials (patriarchs, bishops) who supported iconoclasm, against other bishops, lower clergy, laity and monks, who defended the icons.

The original theological basis for iconoclasm was fairly weak. Arguments relied mostly on the Old Testament prohibition (quoted above). But it was clear that this prohibition was not absolute since God also instructs how to make three dimensional representations of the Cherubim (heavenly spirits or angels) for the Ark of the Covenant, which is also quoted in the Old Testament, just a couple of chapters after the passage that prohibits images (Exodus 25:18-20).

Emperor Constantine V gave a more nuanced theological rationale for iconoclasm. He claimed that each visual representation of Christ necessarily ends in a heresy since Christ, according to generally accepted Christian dogmas, is simultaneously God and man, united without separation, and any visual depiction of Christ either separates these natures, representing Christ’s humanity alone, or confuses them.

The iconophile (pro-icon) counter-argument was most convincingly articulated by St. John of Damascus and St. Theodore the Studite. They claimed that the iconoclast arguments were simply confused. Images of Christ do not depict natures, being either Divine or human, but a concrete person—Jesus Christ, the incarnate Son of God. They claimed that in Christ the meaning of the Old Testament prohibition is revealed: God prohibited any representation of God (or anything that could be worshiped as a god) because it was impossible to depict the invisible God. Any such representation would thus be an idol, essentially a false representation or false god. But in Christ’s person, God became visible, as a concrete human being, so painting Christ is necessary as a proof that God truly, not seemingly, became man. The fact that one can depict Christ witnesses God’s incarnation.

The first phase of iconoclasm ended in 787, when the Seventh Ecumenical (universal) Council of bishops met in Nicaea. This council affirmed the view of the iconophiles, ordering all right-believing (orthodox) Christians to respect holy icons, prohibiting at the same time their adoration as idolatry. Emperor Leo V initiated a second period of iconoclasm in 814, but in 843, Empress Theodora proclaimed the restoration of icons and affirmed the decisions of the Seventh Ecumenical council. This event is still celebrated in the Orthodox Church as the “Feast of Orthodoxy.”

Additional resources:

The Triumph of Images: Icons, Iconoclasm, and the Incarnation

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Ancient and Byzantine mosaic materials

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Video from the Art Institute of Chicago

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm)

The origins of Byzantine architecture

Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330 – 843

Middle Byzantine c. 843 – 1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204 – 1261

Late Byzantine 1261 – 1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

Buildings for a minority religion

Officially Byzantine architecture begins with Constantine, but the seeds for its development were sown at least a century before the Edict of Milan (313) granted toleration to Christianity. Although limited physical evidence survives, a combination of archaeology and texts may help us to understand the formation of an architecture in service of the new religion.

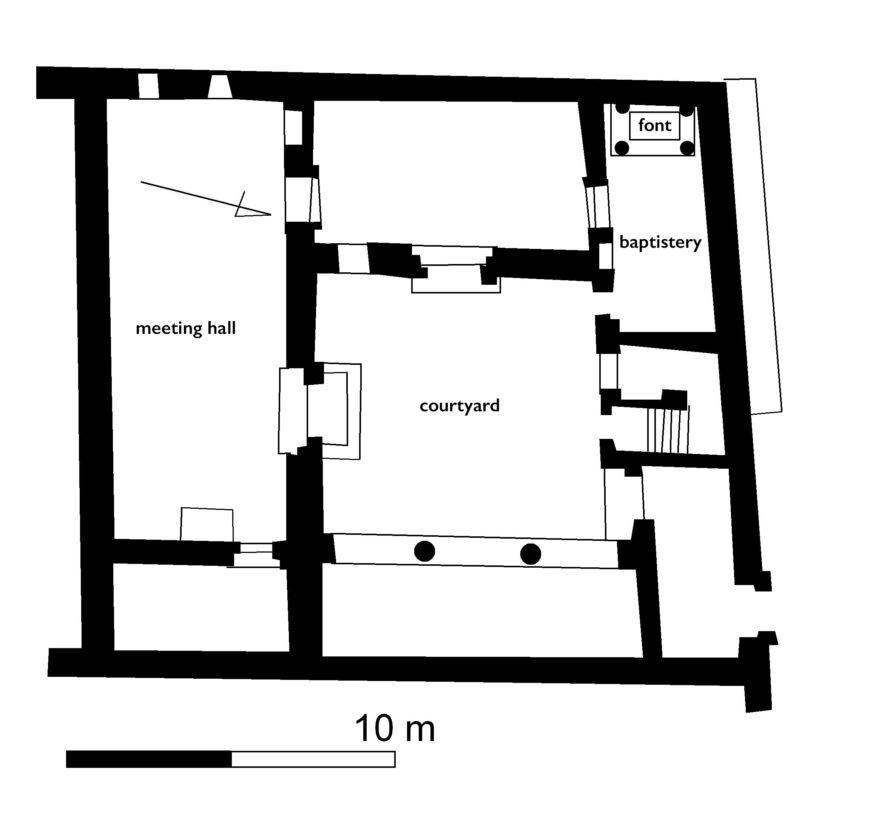

The domus ecclesiae, or house-church, most often represented an adaptation of an existing Late Antique residence to include a meeting hall and perhaps a baptistery. Most examples are known from texts; while there are significant remains in Rome, where they were known as tituli, most early sites of Christian worship were subsequently rebuilt and enlarged to give them a suitably public character, thus destroying much of the physical evidence.

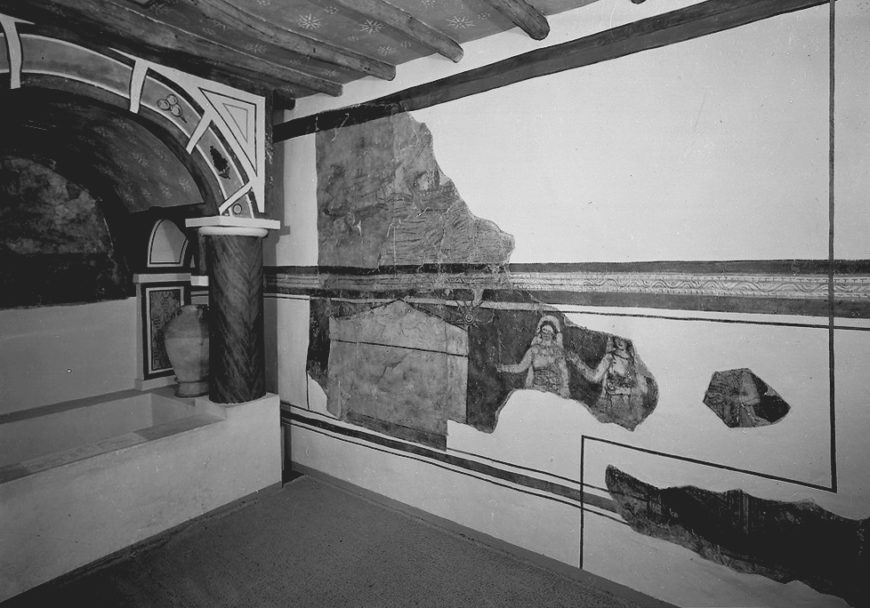

Synagogues and mithraia from the period are considerably better preserved. A notable exception is the Christian House at Dura-Europas in Syria, built c. 200 on a typical courtyard plan. Modified c. 230, two rooms were joined to form a longitudinal meeting hall; another was provided with a piscina (a basin for water) to function as a baptistery for Christian initiation.

Another house-church, considerably modified, was the house of St. Peter at Capharnaum, visited by early pilgrims.

Early Christian burials

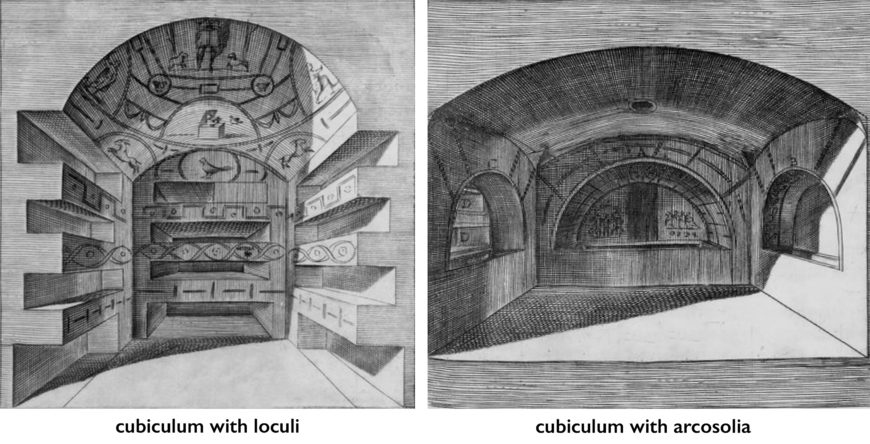

Better evidence survives for burial customs, which were of prime concern in a religion that promised salvation after death. Unlike pagans, who practiced both cremation and inhumation (burial), Christians insisted upon inhumation because of the belief in the bodily resurrection of the dead at the end of days. In addition to areae (above-ground cemeteries) and catacombs (underground cemeteries), Christians required settings for commemorative banquets or refrigeria, a carry-over from pagan practices.

The earliest Christian burials at the Roman catacombs were situated amid those of other religions, but by the end of the second century, exclusively Christian cemeteries are known, beginning with the Catacomb of St. Callixtus on the Via Appia, c. 230. Originally well organized with a series of parallel corridors carved into the tufa (a porous rock common in Italy), the catacombs expanded and grew more labyrinthine over the subsequent centuries. Within, the most common form of tomb was a simple, shelf-like loculus organized in multiple tiers in the walls of the corridors. Small cubicula surrounded with arcosolium tombs provided setting for wealthier burials and provide evidence of social stratification within the Christian community.

Above ground, a simple covered structure provided a setting for the refrigeria, such as the triclia excavated beneath S. Sebastiano, by the entrance to the catacombs.

The development of a cult of martyrs with the early church led to the development of commemorative monuments, usually called martyria, but also referred to in texts as tropaia and heroa. Among those in Rome, the most important was the tropaion marking the tomb of St. Peter in the necropolis on the Vatican Hill.

Increasing visibility

By the time of the Tetrarchy, Christian buildings had become more visible and more public, but without the scale and lavishness of their official successors. In Rome, the meeting hall of S. Crisogono seems to have been founded c. 300 as a visible Christian monument. Similarly in Nikomedia at the same time, the Christian meeting hall was prominent enough to be seen from the imperial palace. Just as the administrative structure of the church and the basic character of Christian worship were established in the early centuries, pre-Constantinian building laid the groundwork for later architectural developments, addressing the basic functions that would be of prime concern in later centuries: communal worship, initiation into the cult, burial, and the commemoration of the dead.

Imperial patronage

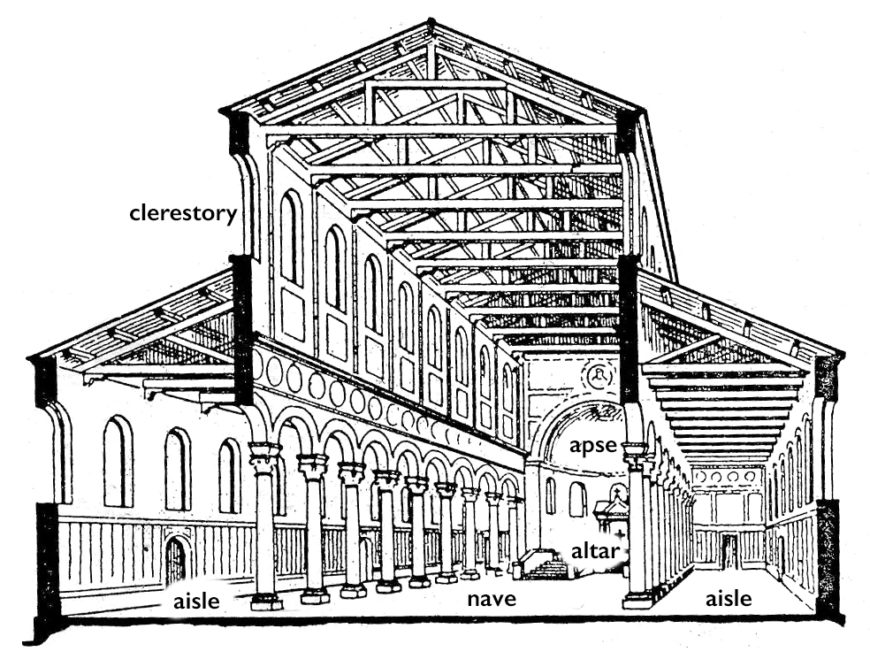

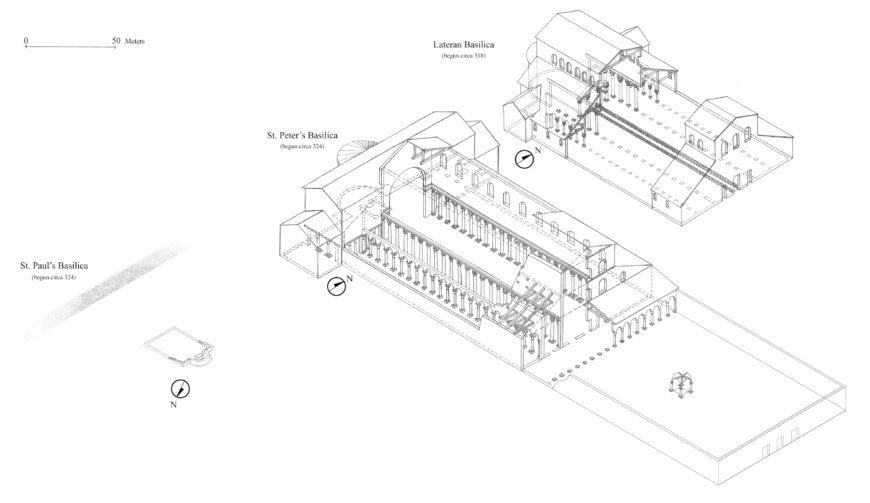

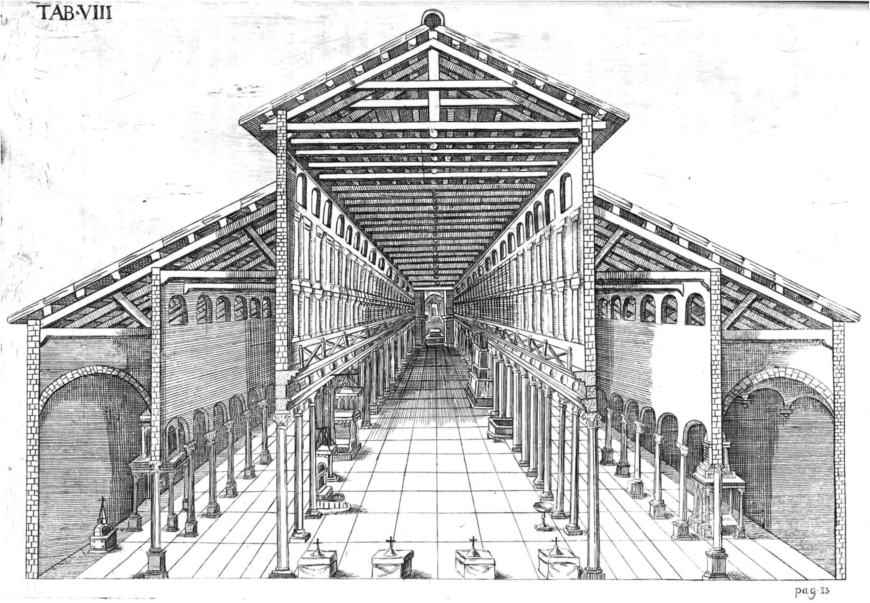

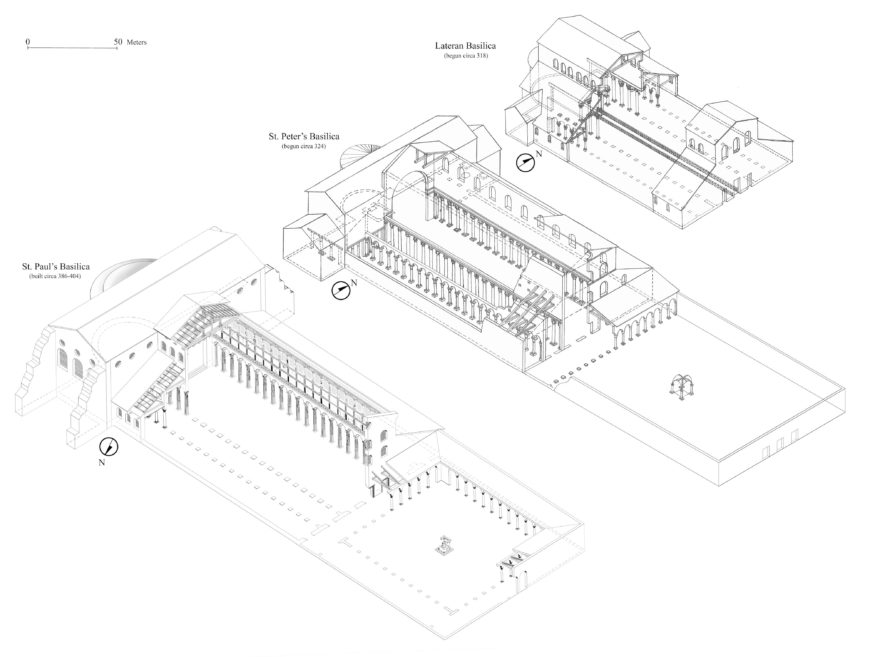

With Constantine’s acceptance of Christianity as an official religion of the Roman Empire in 313, he committed himself to the patronage of buildings meant to compete visually with their pagan counterparts. In major centers like Rome, this meant the construction of huge basilicas capable of holding congregations numbering into the thousands. Although the symbolic associations of the Christian basilica with its Roman predecessors have been debated, it thematized power and opulence in ways comparable to but not exclusive to imperial buildings.

Formally, the basilica also stood in sharp contrast to the pagan temple, at which worship was conducted out of doors. The church basilica was essentially a meeting house, not a sacred structure, but a sacred presence was created by the congregation joining in common prayer—the people, not the building, comprised the ekklesia (the Greek word for “church”).

The Lateran basilica, originally dedicated to Christ, was begun c. 313 to serve as Rome’s cathedral, built on the grounds of an imperial palace, donated to be the residence of the bishop. Five-aisled in plan, the basilica’s tall nave was illuminated by clerestory windows, which rose above coupled side aisles along the flanks and terminated in an apse at the west end, which held seats for the clergy. Before the apse, the altar was surrounded by a silver enclosure, decorated with statues of Christ and the Apostles.

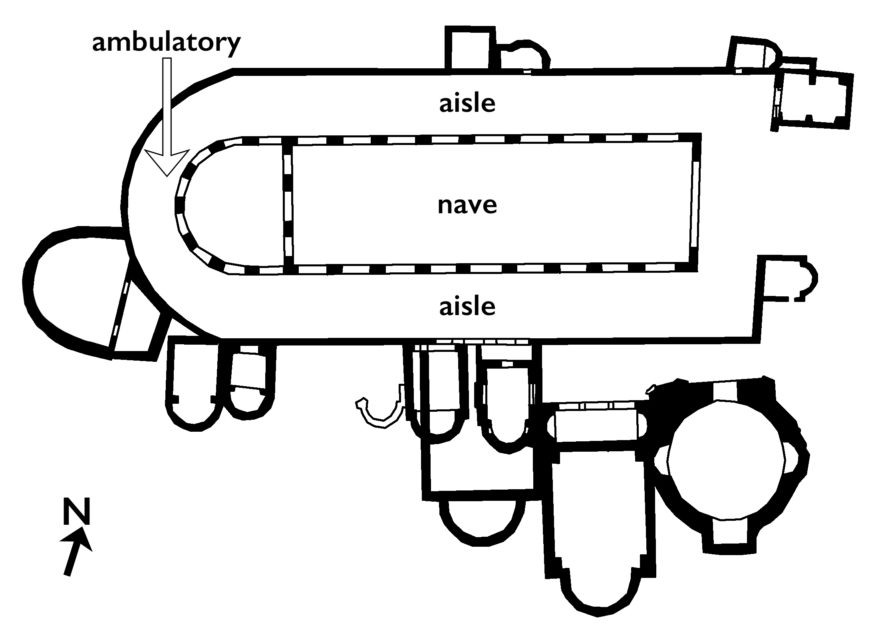

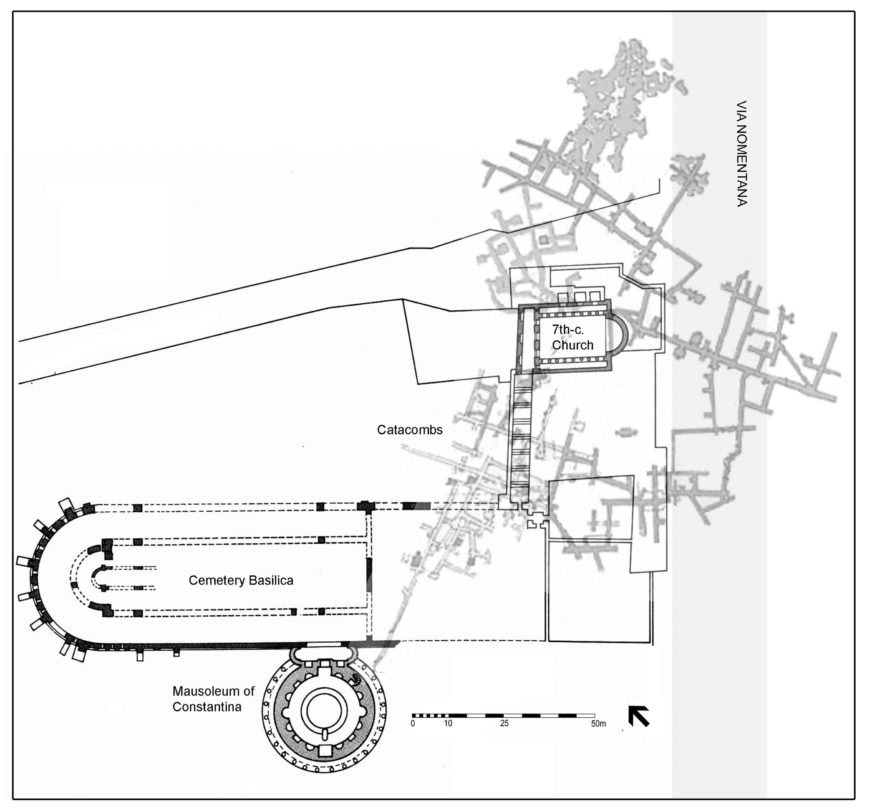

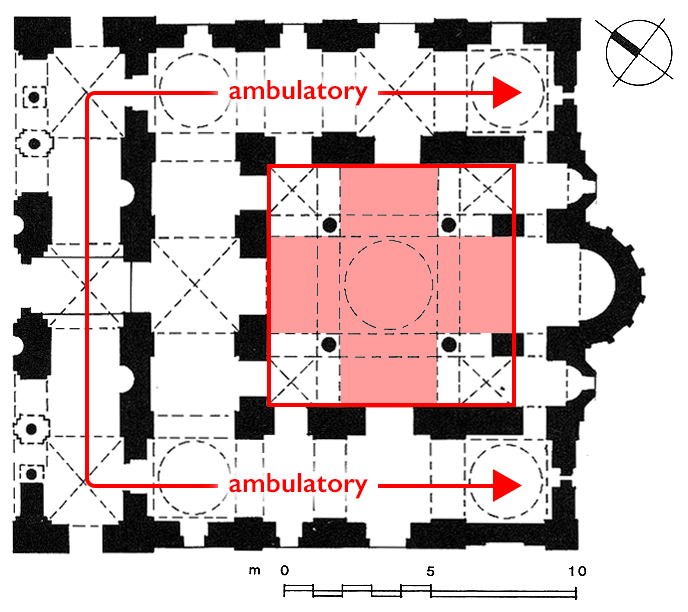

In addition to congregational churches, among which the Lateran stands at the forefront, a second type of basilica (or ambulatory basilica) appeared in Rome at the same time, set within the cemeteries outside the city walls, apparently associated with the venerated graves of martyrs. S. Sebastiano, probably originally the Basilica Apostolorum, which may have been begun immediately before the the Peace of the Church, rose on the site of the earlier triclia, in which graffiti testify to the special veneration of Peter and Paul at the site. These so-called cemetery basilicas provided a setting for commemorative funeral banquets. Essentially covered burial grounds, the floors of the basilicas were paved with graves and their walls enveloped by mausolea.

In plan they were three-aisled, with the aisle continuing into an ambulatory surrounding the apse at the west end. By the end of the fourth century, however, the practice of the funerary banquet was suppressed, and the grand cemetery basilicas were either abandoned or transformed into parish churches.

Martyria

Constantine also supported the construction of monumental martyria.

Most important in the West was St. Peter’s basilica in Rome, begun c. 324, originally functioning as a combination of cemetery basilica and martyrium, sited so that the focal point was the marker at the tomb of Peter, covered by a ciborium (canopy) and located at the chord of the western apse. The enormous five-aisled basilica served as the setting for burials and the refrigeria. To this was juxtaposed a transept – essentially a transverse, single-aisled nave—which provided access to the saint’s tomb. The eastern atrium seems to have been slightly later in date.

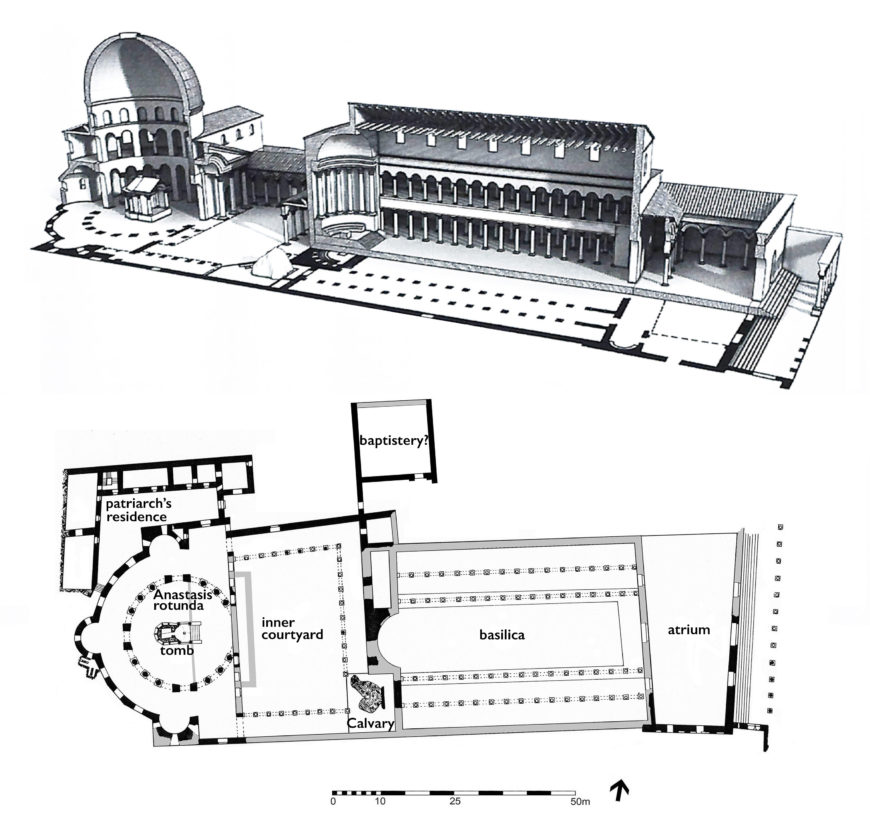

In the Holy Land, major shrines similarly juxtaposed congregational basilicas with centrally-planned commemorative structures housing the venerated site. At Bethlehem (c. 324), a short five-aisled basilica terminated in an octagon marking the site of Christ’s birth. At Jerusalem, Constantine’s church of the Holy Sepulchre (dedicated 336) marked the sites of Christ’s Crucifixion, Entombment, and Resurrection, and consisted of a sprawling complex with an atrium opening from the main street of the city; a five-aisled, galleried congregational basilica; an inner courtyard with the rock of Calvary in a chapel at its southeast corner; and the aedicula of the Tomb of Christ, freed from the surrounding bedrock, to the west. The Anastasis Rotunda, enclosing the Tomb aedicula, was completed only after Constantine’s death.

Most martyria were considerably simpler, often no more than a small basilica. At Constantine’s Eleona church on the Mount of Olives, for example, a simple basilica was constructed above the cave where Christ had taught the Apostles.

Pilgrims’ accounts, such as that left by the Spanish nun Egeria (c. 380), provide a fascinating view of life at the shrines. These great buildings played an important role in the development of the cult of relics, but they were less important for the subsequent development of Byzantine architecture.

New Rome

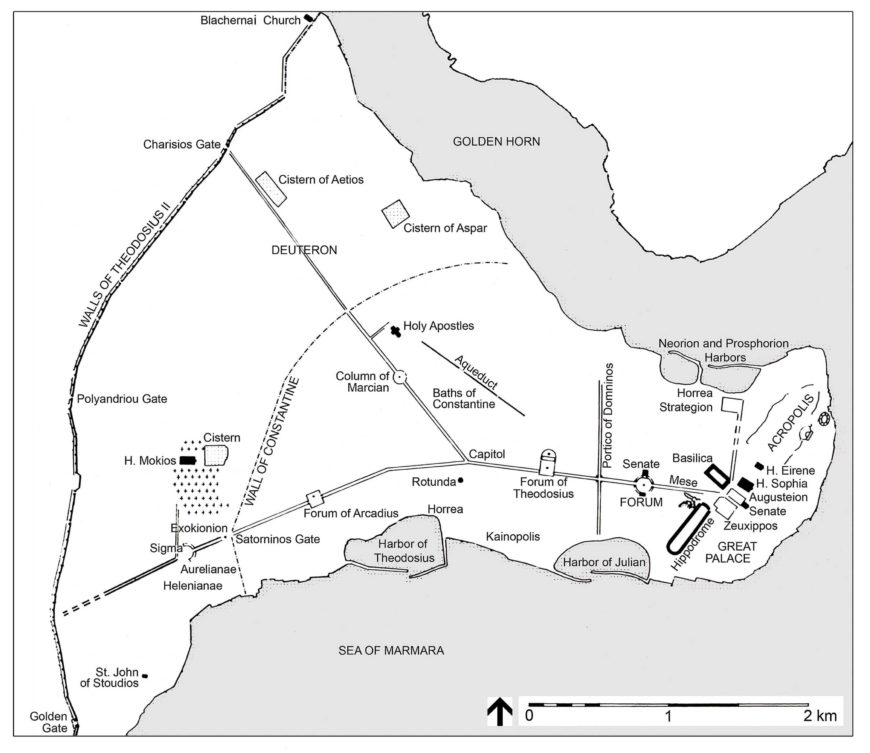

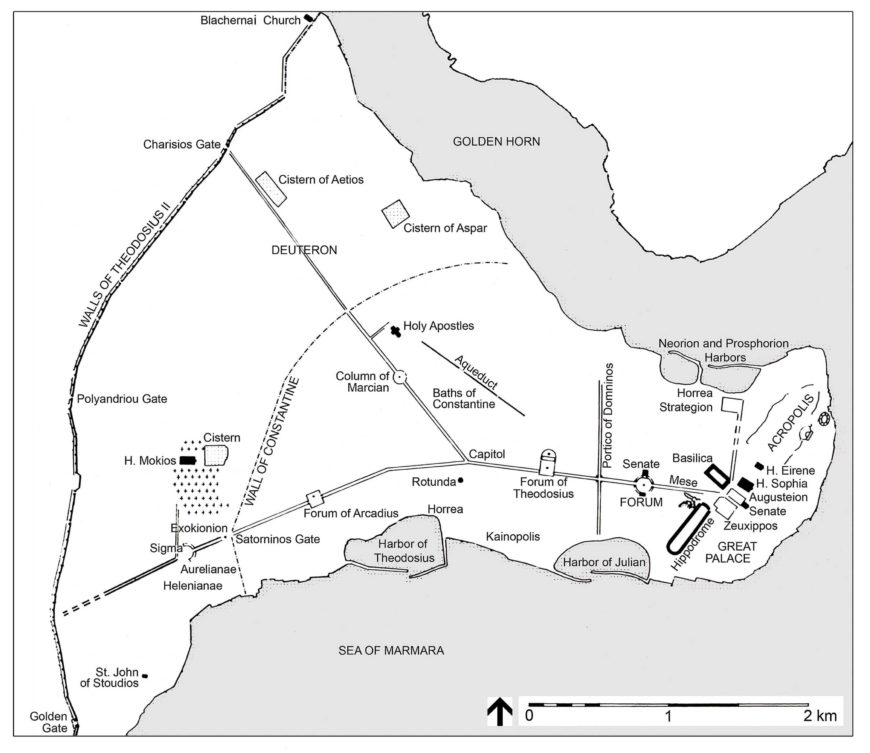

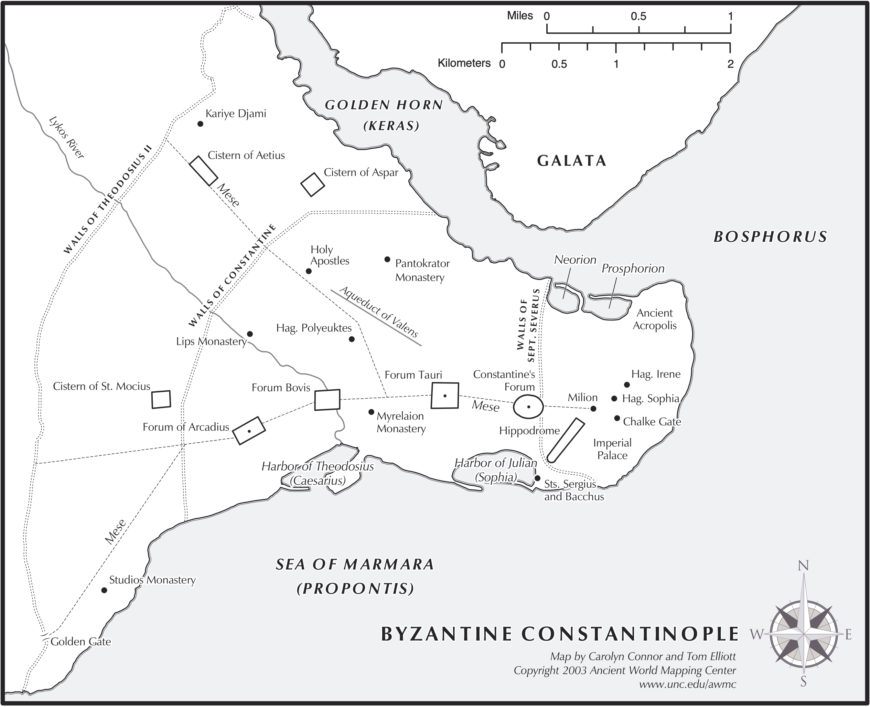

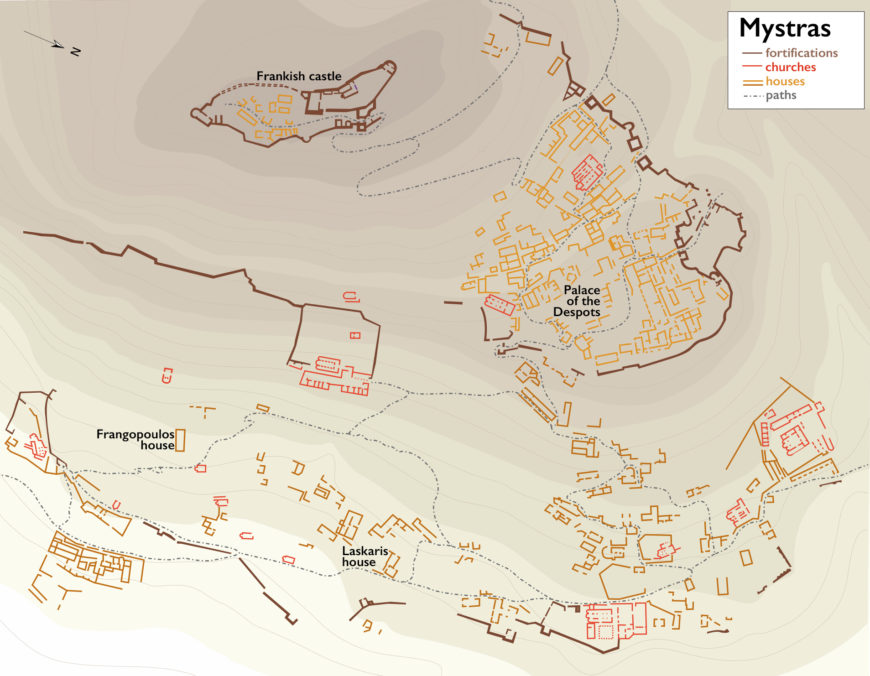

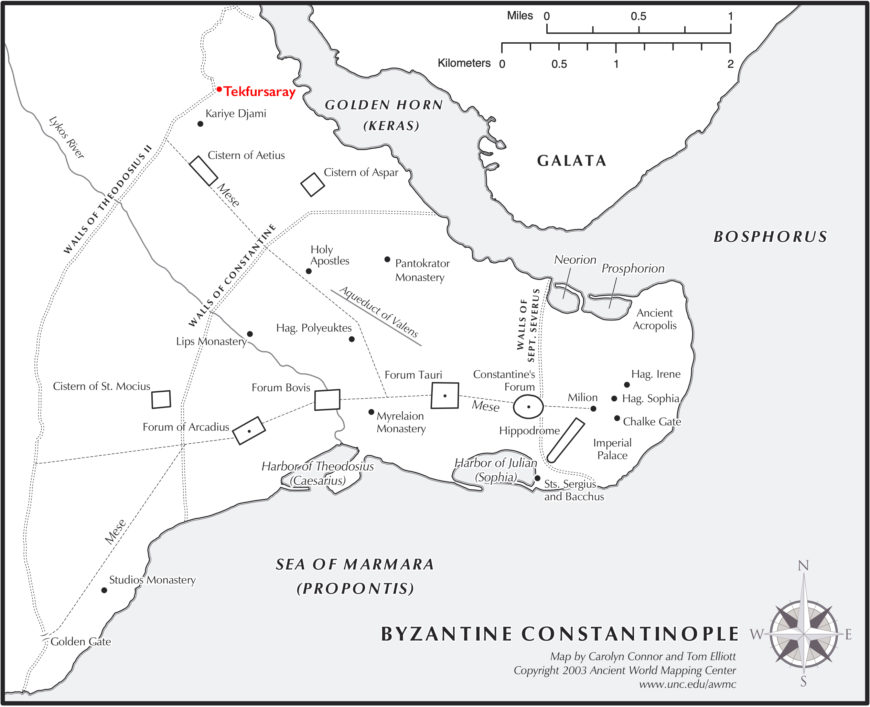

In addition to his acceptance of Christianity, Constantine’s other great achievement was the establishment of a new imperial residence and subsequent capital city in the East, strategically located on the straits of the Bosphorus. Nova Roma or Constantinople, as laid out in 324-330, expanded the urban armature of the old city of Byzantion westward to fill the peninsula between the Sea of Marmara and the Golden Horn, combining elements of Roman and Hellenistic city planning.

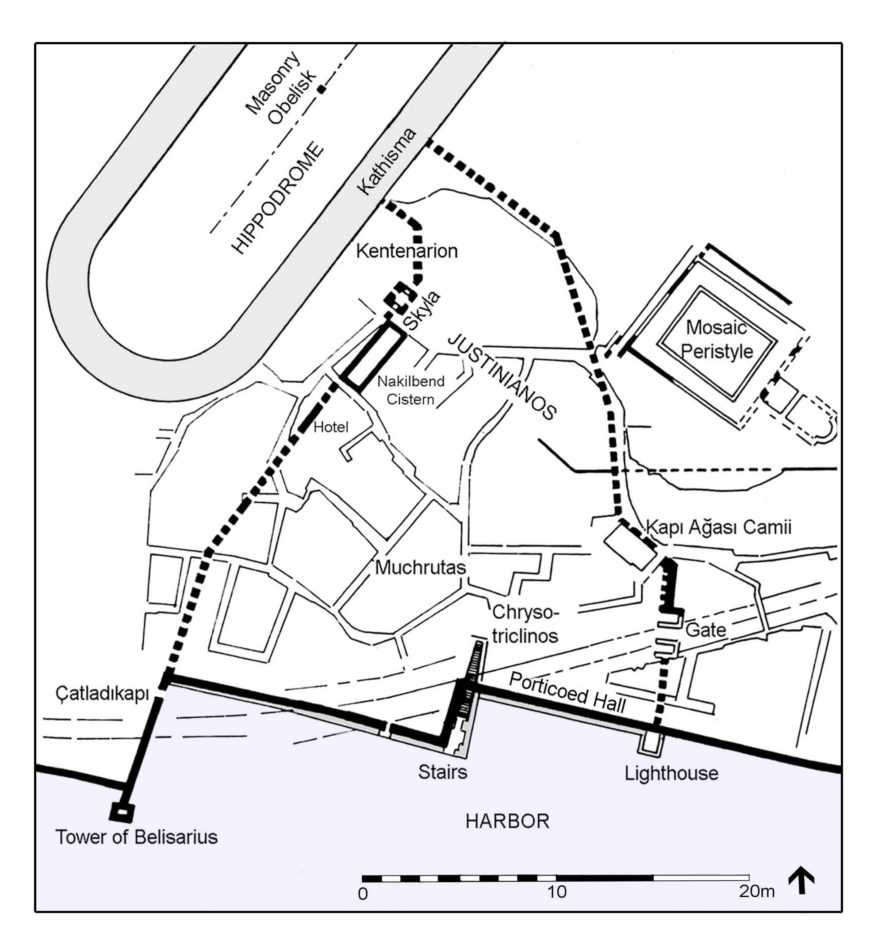

Like old Rome, the new city of Constantine was built on seven hills and divided into fourteen districts; its imperial palace lay next to its hippodrome, which was similarly equipped with a royal viewing box. As in Rome, there were a senate house, a Capitol, great baths, and other public amenities; imperial fora provided its public spaces; triumphal columns, arches, and monuments, including a colossus of the emperor as Apollo-Helios, and a variety of dedications imparted mimetic associations with the old capital.

Constantine’s own mausoleum was established in a position that encouraged a comparison with that of Augustus’s mausoleum in Rome; the adjoining cruciform basilica—the church of the Holy Apostles—was apparently added by his sons. Beyond the much-altered porphyry column that once stood at the center of his forum, however, virtually nothing survives from the time of Constantine; the city continued to expand long after its foundation.

Next: read about Early Byzantine architecture after Constantine

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Early Byzantine architecture after Constantine

Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330 – 843

Middle Byzantine c. 843 – 1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204 – 1261

Late Byzantine 1261 – 1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

Basilicas and new forms

After the time of Constantine, a standardized church architecture emerged, with the basilica for congregational worship dominating construction.

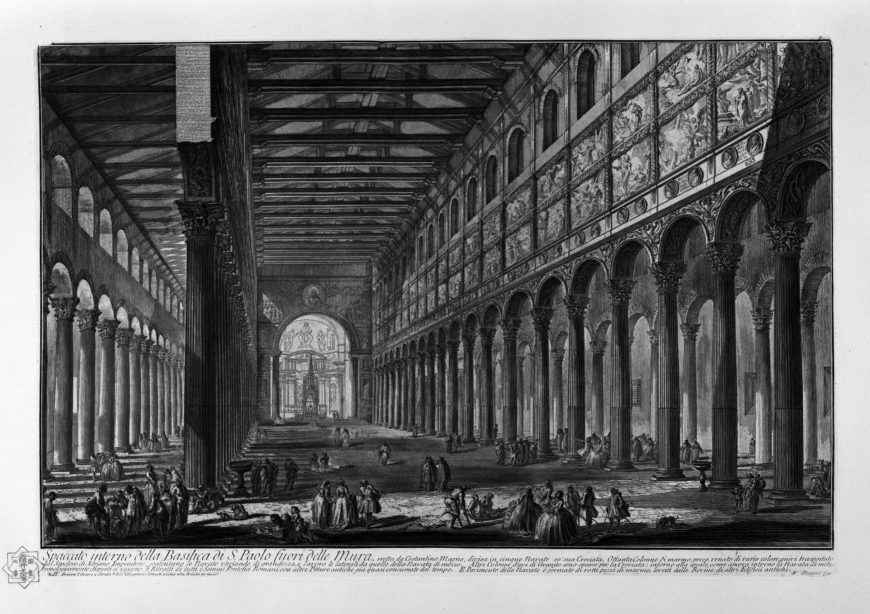

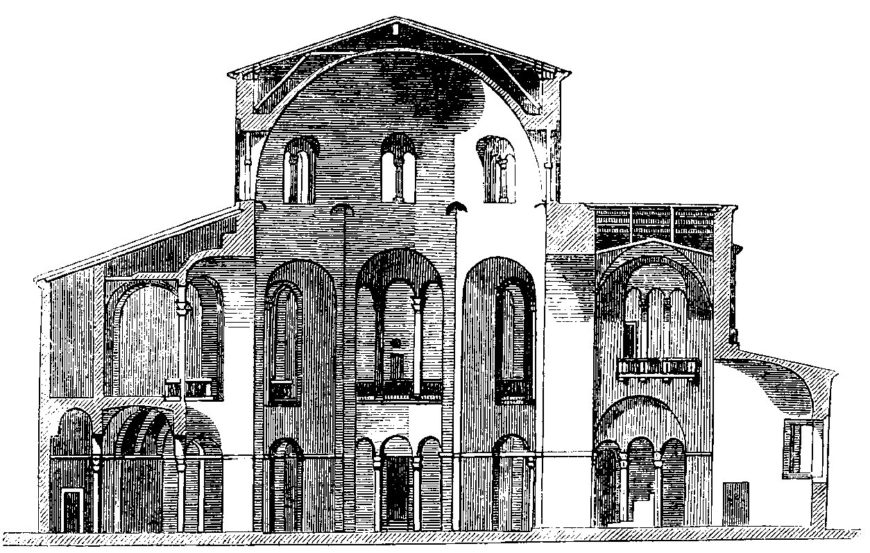

There were numerous regional variations: in Rome and the West, for example, basilicas usually were elongated without galleries, as at S. Sabina in Rome (522-32) or S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (c. 490).

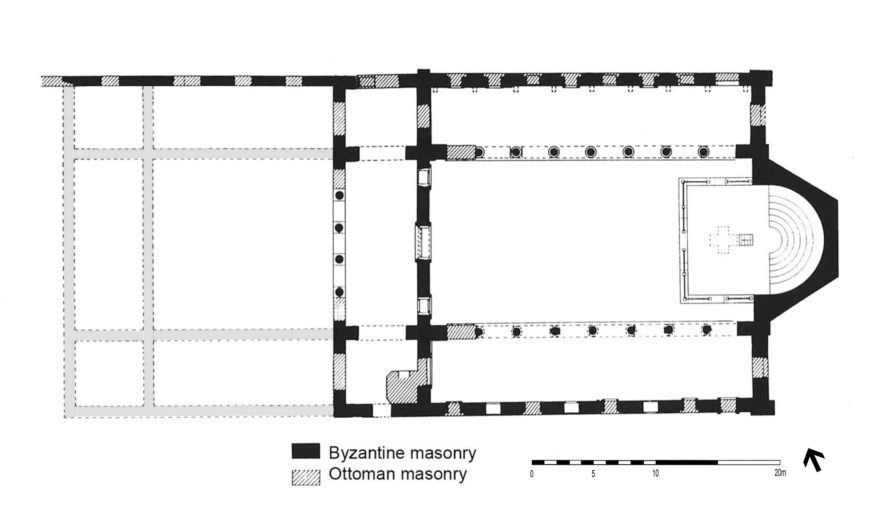

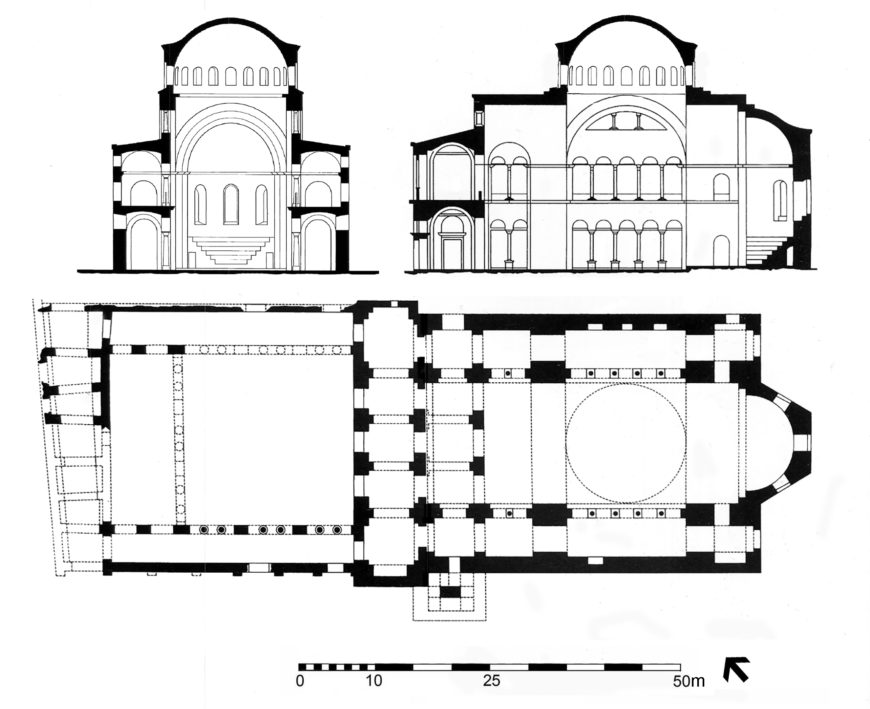

In the East the buildings were more compact and galleries were more common, as at St. John Stoudios in Constantinople (458) or the Achieropoiitos in Thessaloniki (early fifth century) (view plan and elevation).

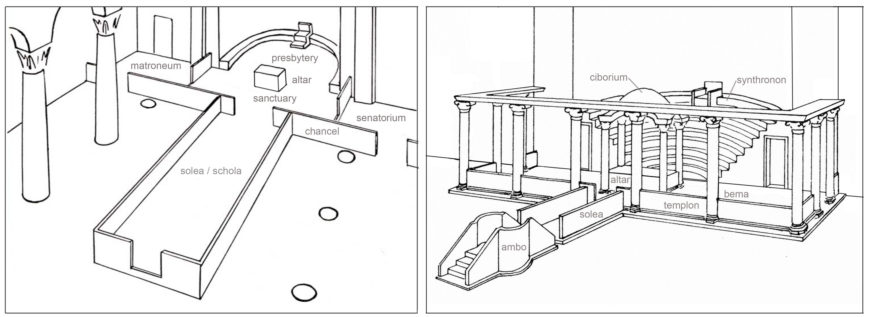

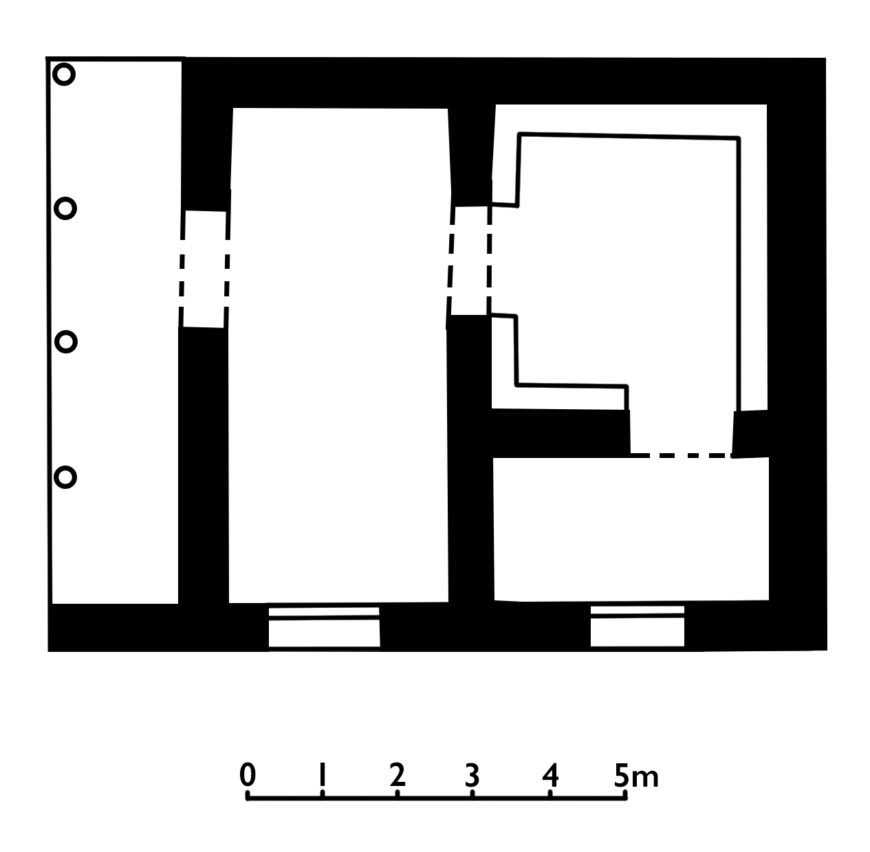

By the fifth century, the liturgy had become standardized, but, again, with some regional variations, evident in the planning and furnishing of basilicas. In general, the area of the altar was enclosed by a templon barrier, with semicircular seating for the officiants (the synthronon) in the curvature of the apse. The altar itself was covered by a ciborium. Within the nave, a raised pulpit or ambo provided a setting for the Gospel readings.

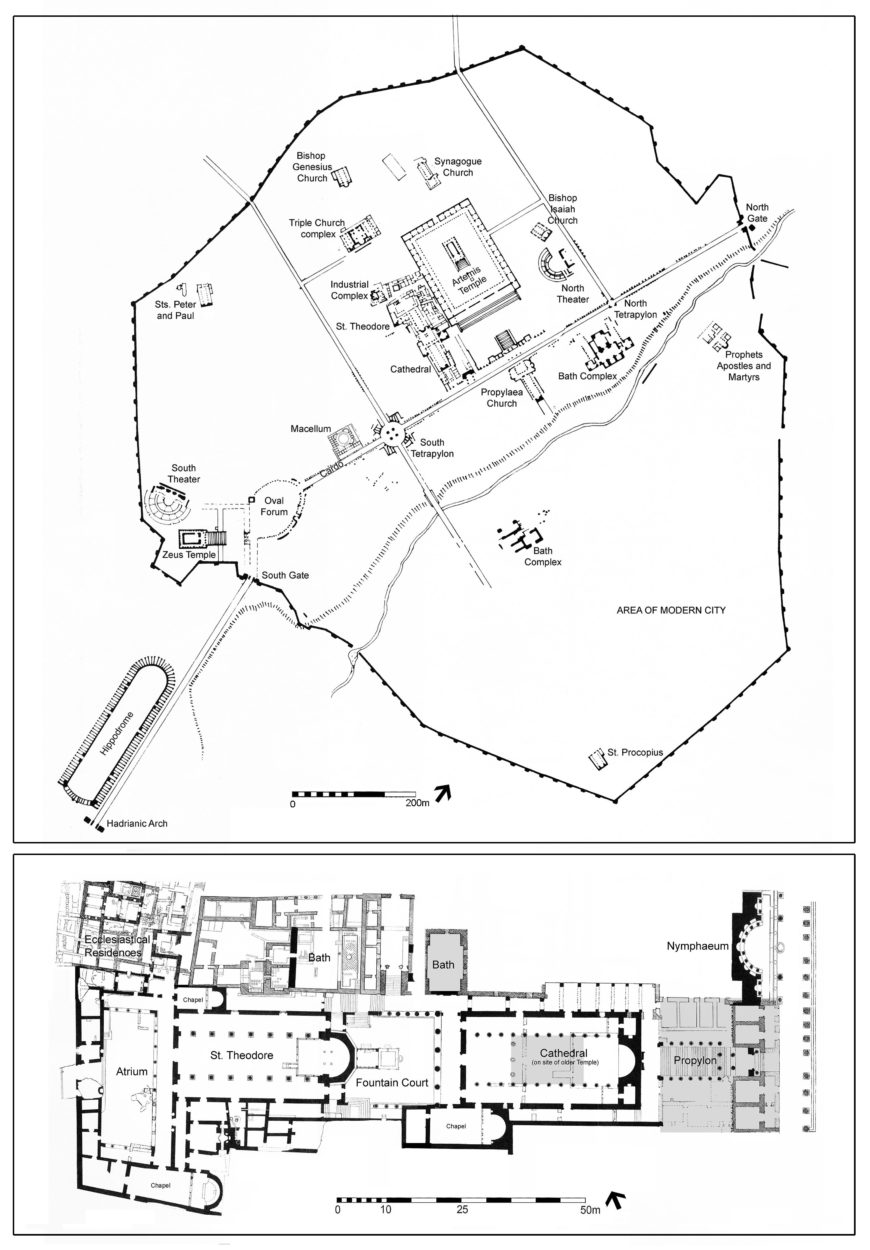

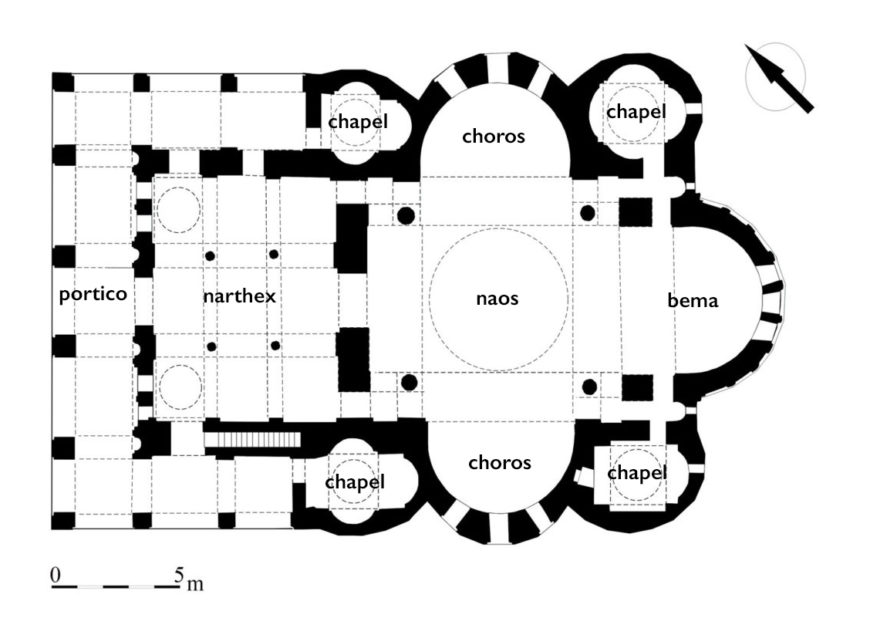

The liturgy probably had less effect on the creation of new architectural designs than on the increasing symbolism and sanctification of the church building. Some new building types emerge, such as the cruciform church, the tetraconch, octagon, and a variety of centrally planned structures. Such forms may have had symbolic overtones; for example, the cruciform plan may be either a reflection of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople or associated with the life-giving cross, as at S. Croce in Ravenna or SS. Apostoli in Milan. Other innovative designs may have had their origins in architectural geometry, such as the enigmatic S. Stefano Rotondo (468-83) in Rome. The aisled tetraconch churches, once thought to be a form associated with martyria, are most likely cathedrals or metropolitan churches. The early fifth-century tetraconch in the Library of Hadrian in Athens was probably the first cathedral of the city; that at Selucia Pieria-Antioch, from the late fifth century, was possibly a metropolitan church.

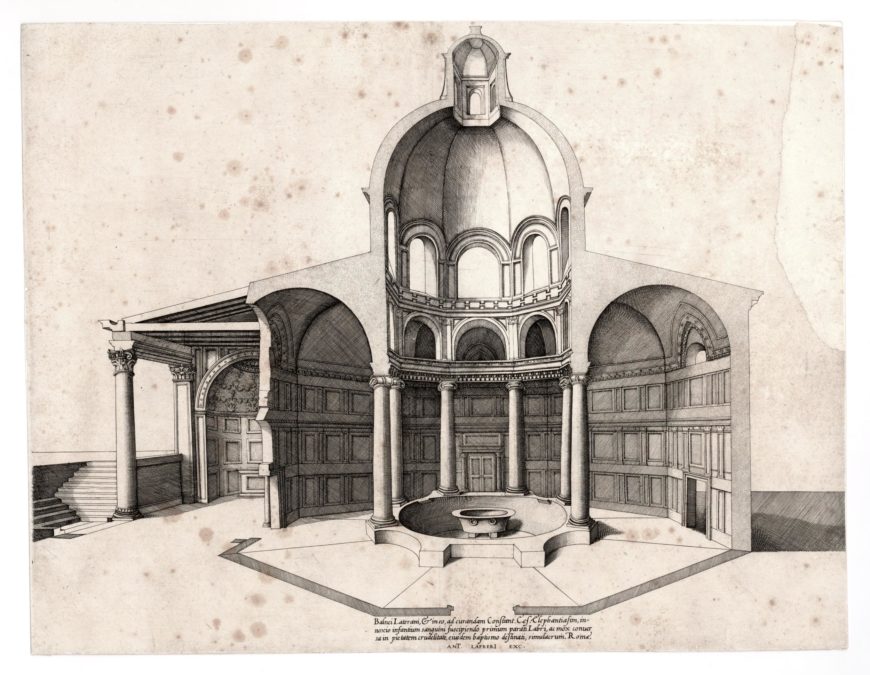

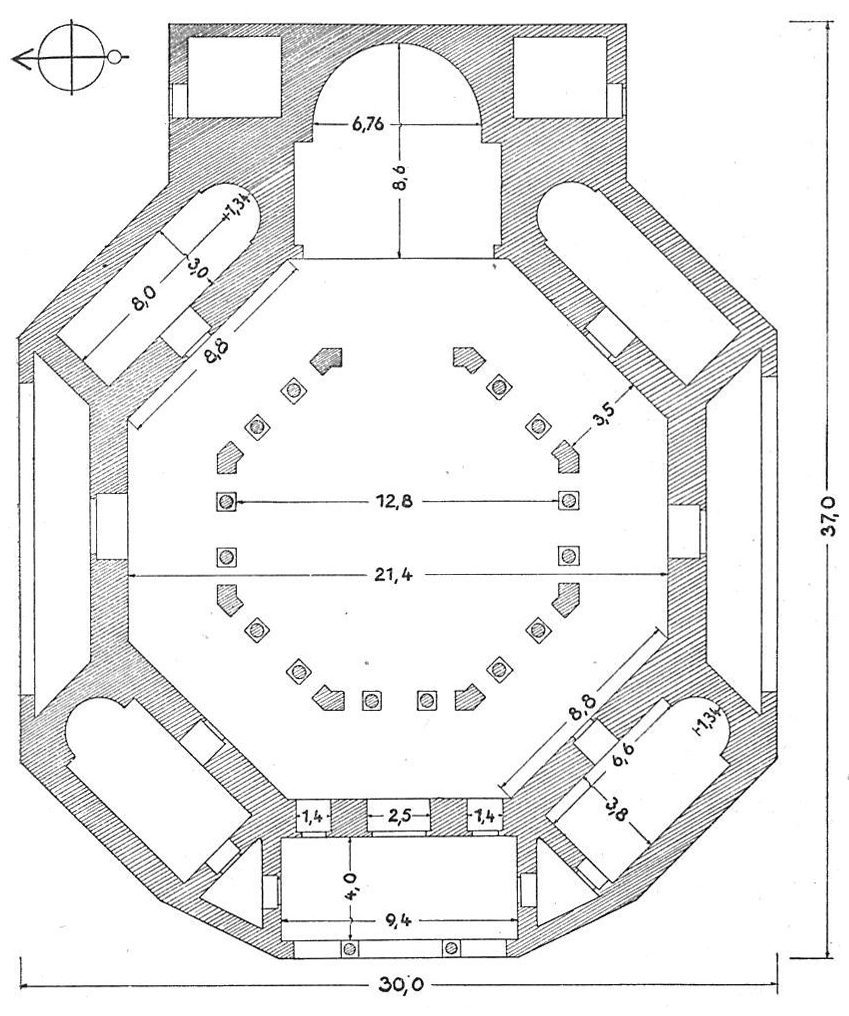

Baptisteries

Baptisteries also appear as prominent buildings throughout the Empire, necessary for the elaborate ceremonies addressed to adult converts and catechumens. Most common was a symbolically resonant, octagonal building housing the font and attached to the cathedral, as with the Orthodox (or Neonian) Baptistery at Ravenna, c. 400-450. In Rome, the Lateran’s baptistery was an independent, octagonal structure that stood north of the basilica’s apse. Built under Constantine, the baptistery expanded under Pope Sixtus III in the fifth century with the addition of an ambulatory around its central structure. The inscription St. Ambrose composed for his baptistery at Milan clarifies the symbolism of such eight-sided buildings:

The eight-sided temple has risen for sacred purposes

The octagonal font is worthy for this task.

It is seemly that the baptismal hall should arise in this number

By which true health returns to people

By the light of the resurrected Christinscription attributed to St. Ambrose of Milan

Associated with death and resurrection, the planning type derives from Late Roman mausolea, although not directly from the Anastasis Rotunda. Variations abound: at Butrint (in modern Albania) and Nocera (in southwestern Italy), for example, the baptisteries have ambulatories; in North Africa, the architecture tends to remain simple, while the form of the font is elaborated. With the change to infant baptism and a simplified ceremony, however, monumental baptisteries cease to be constructed after the sixth century.

Martyria and Mausolea

Although the church gradually eliminated the great funeral banquets at the graves of martyrs, the cult of martyrs was manifest in other ways, notably the importance of pilgrimage and the dissemination of relics. In spite of this, there was not a standard architectural form for the martyria, which instead seem to depend on site-specific conditions or regional developments. In Rome, for example, S. Paolo fuori le mura (St. Paul Outside the Walls), begun 384, follows the model of St. Peter’s in adding a transept to a huge five-aisled basilica.

At Thessaloniki, the basilica of H. Demetrios (late fifth century) incorporated the remains of a crypt and other structures associated with the Roman bath where Demetrius was martyred.

At rural locations, large complexes emerged, as at Qal’at Sam’an, built c. 480-90 in Syria, which had four basilicas radiating from an octagonal core, where the stylite saint’s column stood.

An entire city (Abu Mena), with church architecture of increasing complexity, grew around the venerated tomb of St. Menas in Egypt.

At Hierapolis in Asia Minor, a large octagonal complex was built at the site of the tomb of St. Philip (view plan).

At Ephesus, a cruciform church arose at the tomb of St. John the Evangelist.

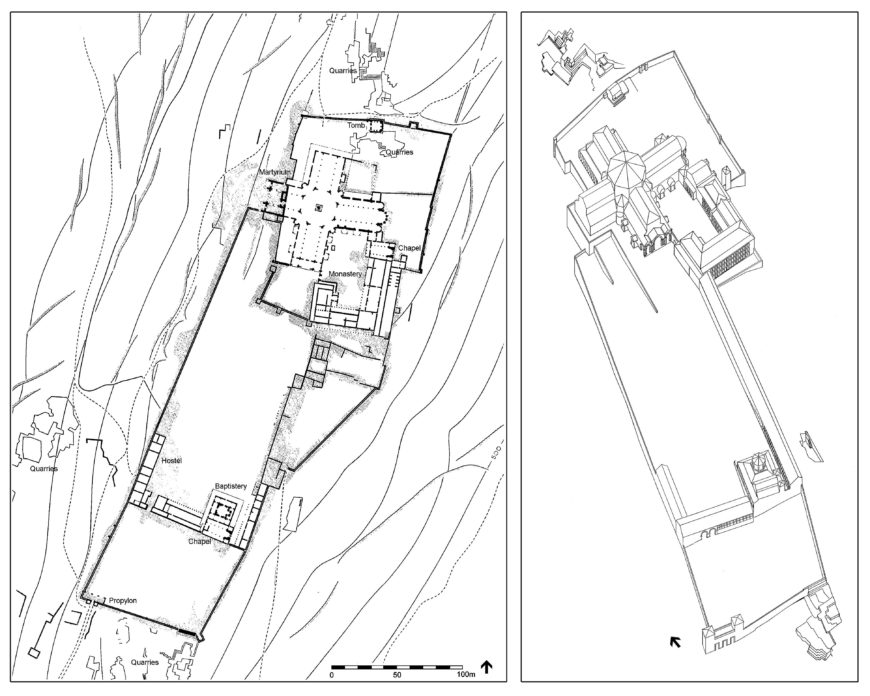

Others were simpler in form. At the martyrium of St. Thekla at Meryemlik, c. 480, a three-aisled basilica was added above her holy cave. At Sinai, the sixth-century basilica was augmented by subsidiary chapels along its sides, but the holy site – the Burning Bush – lay outside, immediately to the east of its apse (view plan).

The desire for privileged burial perpetuated the tradition of Late Antique mausolea, which were often octagonal or centrally planned. In Rome the fourth-century mausolea of Helena and Constantina were attached to cemetery basilicas.

Cruciform chapels seem to be a new creation, with a shape that derived its meaning from the life-giving Cross, a relationship emphasized in the well-preserved Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, built c. 425, in Ravenna, which was originally attached to a cruciform church dedicated to S. Croce.

In Constantinople, the successors of Constantine were buried in the rotunda at the church of the Holy Apostles or its dependencies.

Monasticism

Monasticism began to play an increasingly important role in society, but from the perspective of architecture, early monasteries lacked systematic planning and were dependent on site-specific conditions. The coenobitical system (communal monasticism) included living quarters, with cells for the monks, as well as a refectory for common dining and a church or chapel for common worship. Evidence is preserved in the desert communities of Egypt and Palestine. At the Red Monastery at Sohag, the formal spaces are contained within a fortress-like complex, although it is unclear where with or without the enclosure the monks actually lived. In the Judean Desert, a variety of hermits’ cells are preserved – simple caves carved into the rough landscape.

Urban Planning

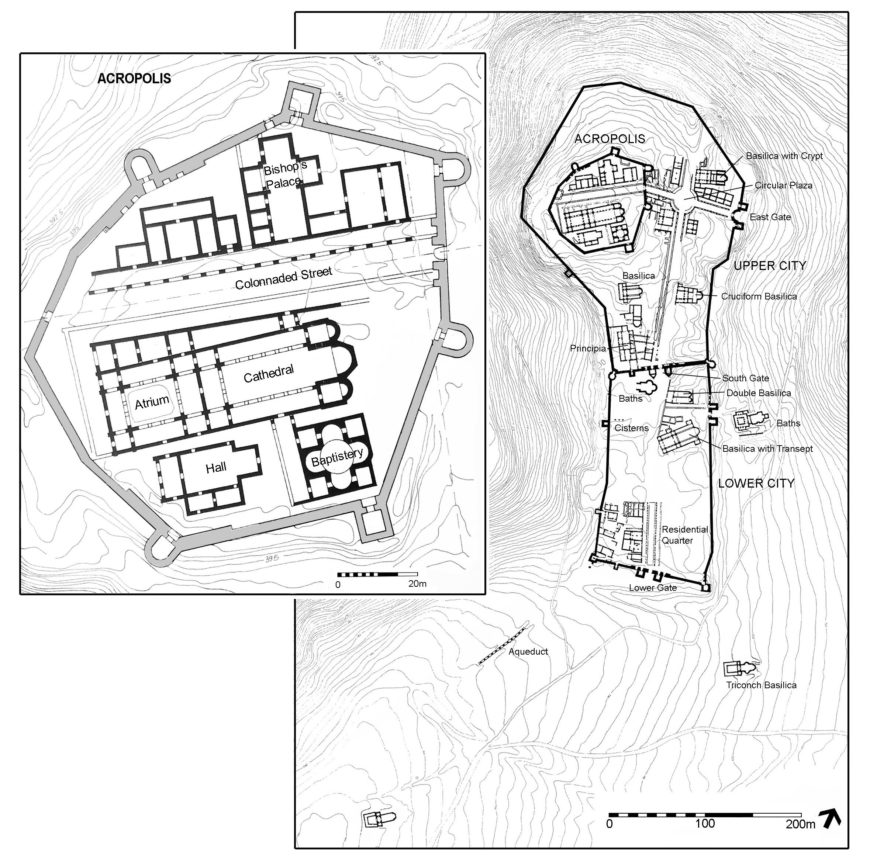

In general, urban planning in this period follows Roman and Hellenistic models, as Justinian’s new city of Iustiniana Prima (Caracin Grad, in modern Serbia) amply demonstrates.

At Gerasa (in modern Jordan), Thessaloniki, and elsewhere, existing city plans were reconfigured to give prominence to the new Christian structures.

In Jerusalem and Athens, there may have been an intentional visual juxtaposition of the new Christian cathedral with the abandoned Jewish or pagan temple.

While the Theodosian Code legislated the cessation of pagan worship, it recommended the preservation of the temple building and its contents because of their artistic value. The transformation of temples into churches was rare before the sixth century.

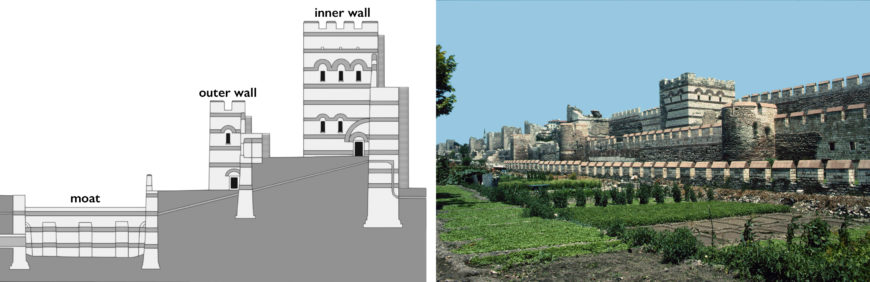

Defensive architecture followed Roman practices.

The walls of Constantinople, added by Theodosius II (412-13) stand as a singular achievement, combining two lines of defensive walls with a moat. In a like manner, the system of aqueducts and cisterns at Constantinople expanded upon established Roman technology to create the most extensive water system in Antiquity.

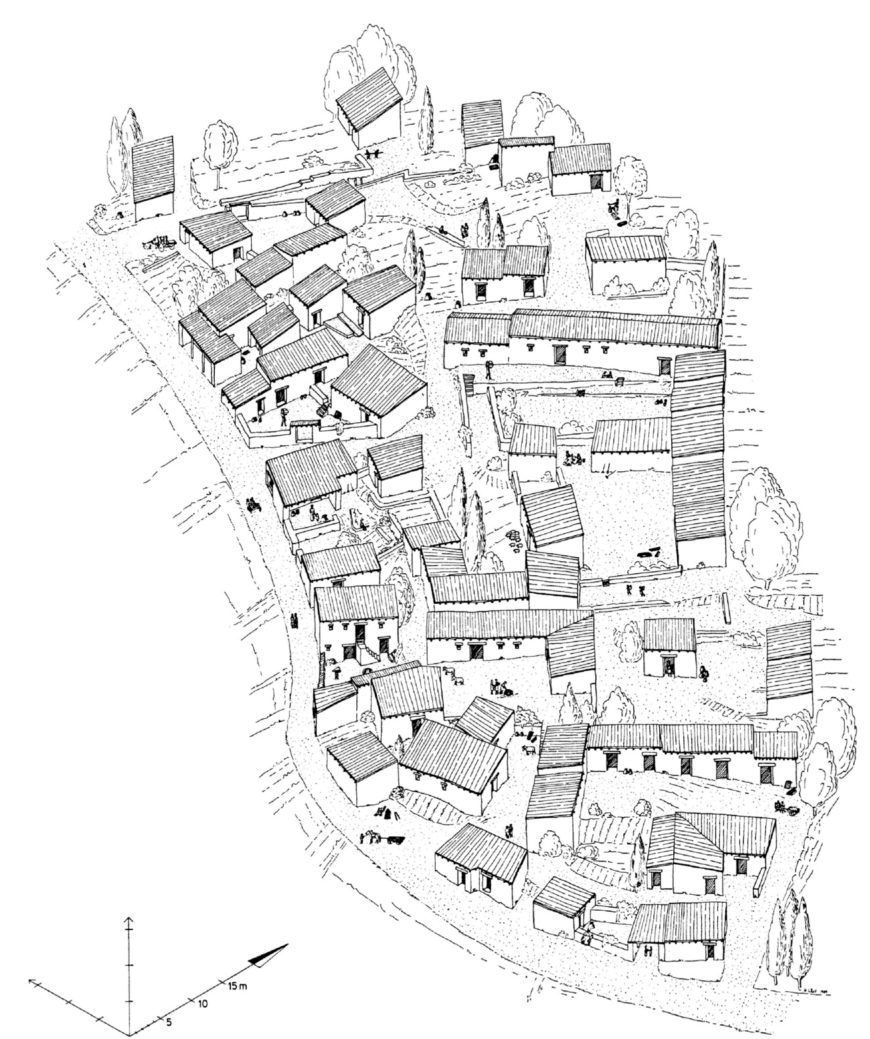

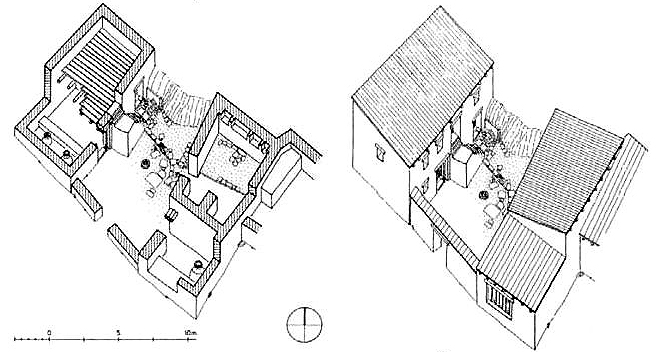

Domestic Architecture

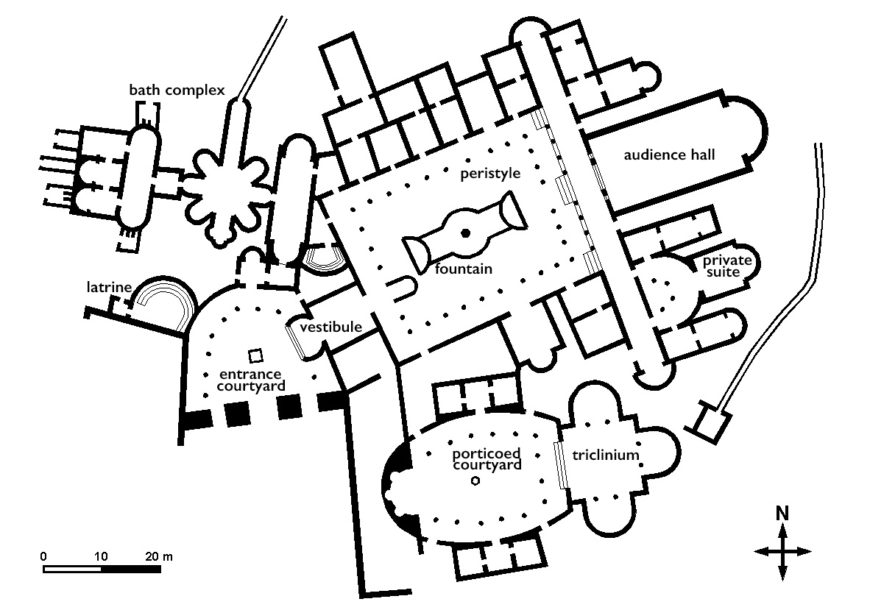

Standard planning continued in domestic architecture as well. Large houses excavated in Asia Minor (Sardis, Ephesus), North Africa (Carthage, Spaitla, Apollonia), Italy (Ravenna, Piazza Armerina), Greece (Athens, Argos), and elsewhere include porticoed gardens, audience halls, and triclinia (dining rooms). The Great Palace in Constantinople and the so-called Palace of Theodoric in Ravenna were essentially elaborations on or repetitions of the Late Roman villa. Perhaps the most significant changes in the Late Antique domus (house) were the increasing size and number of ceremonial spaces (audience halls and triclinia) – as at the early fourth century villa at Piazza Armerina (in Sicily) – and the incorporation of chapels into the domestic setting – as at the Palace of the Dux at Apollonia (in modern Libya). The latter phenomenon is indicative of the growing importance of private worship and was a source of growing concern in ecclesiastical legislation. With significant economic and social changes, however, by the end of the period under discussion, the domus disappeared.

Next: read about innovative architecture in the age of Justinian

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Woman with Scroll

by DR. EVAN FREEMAN and DR. ANNE MCCLANAN

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Evan and Anne discuss Marble Portrait Bust of a Woman with a Scroll, late 4th–early 5th century C.E., pentelic marble, 53 x 27.5 x 22.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection)

Additional resources:

Byzantine Mosaic of a Personification, Ktisis

by DR. EVAN FREEMAN and DR. ANNE MCCLANAN

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Evan and Anne discuss Fragment of a Floor Mosaic with a Personification of Ktisis, ca. 500–550 C.E. (with modern restoration), marble and glass, 151.1 x 199.7 x 2.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Additional resources:

Innovative architecture in the age of Justinian

Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330 – 843

Middle Byzantine c. 843 – 1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204 – 1261

Late Byzantine 1261 – 1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

New trends

Although standardized church basilicas continued to be constructed, by the end of the fifth century, two important trends emerge in church architecture: the centralized plan, into which a longitudinal axis is introduced, and the longitudinal plan, into which a centralizing element is introduced.

The first type may be represented by the ruined church of the Theotokos on Mt. Gerizim (in modern Israel), c. 484, which has a developed sanctuary bay projecting beyond an aisled octagon with radiating chapels; the second by the so-called Domed Basilica at Meriamlik (on the southern coast of Turkey), c. 471-94, which superimposed a dome on a standard basilican nave (view plan). Both may be attributed to the patronage of emperor Zeno.

The reign of Justinian

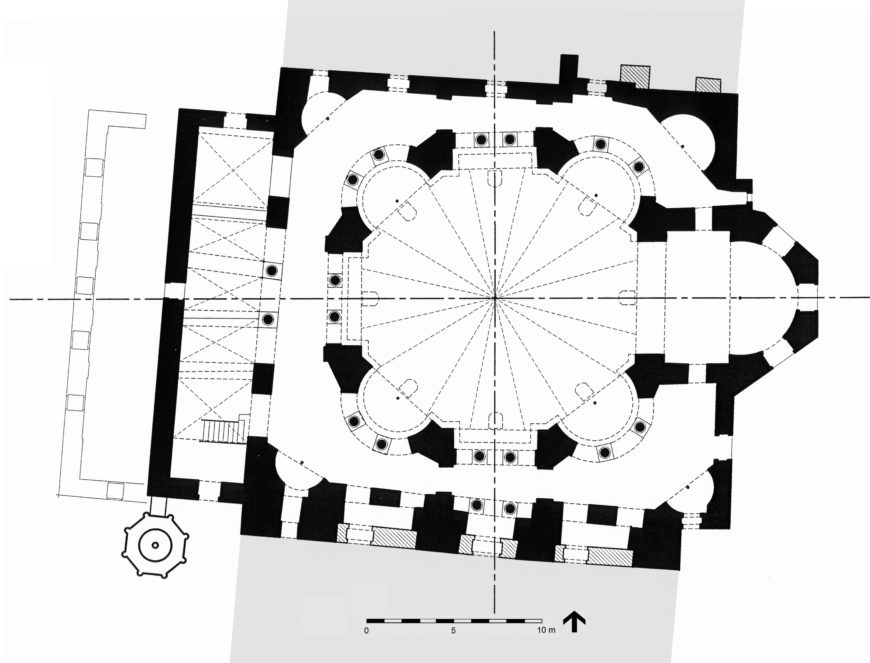

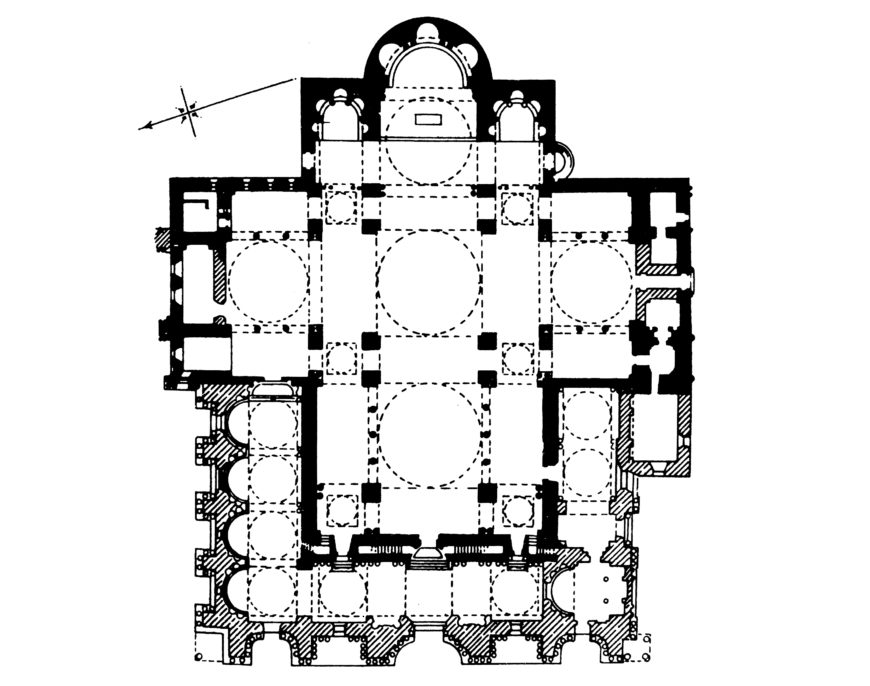

Both trends are further developed during the reign of Justinian (reigned 527 to 565). HH. Sergios and Bakchos in Constantinople, completed before 536, and S. Vitale in Ravenna, completed c. 546/48, for example, are double-shelled octagons (view plan of San Vitale) of increasing geometric sophistication, with masonry domes covering their central spaces, perhaps originally combined with wooden roofs for the side aisles and galleries.

Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

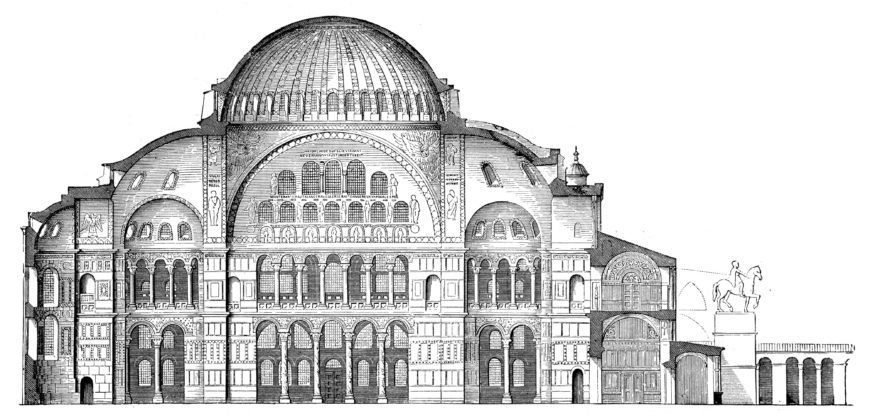

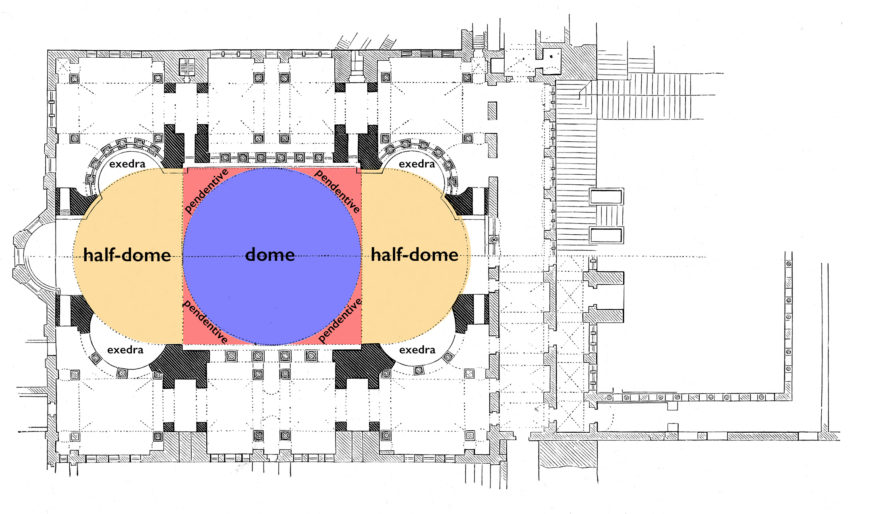

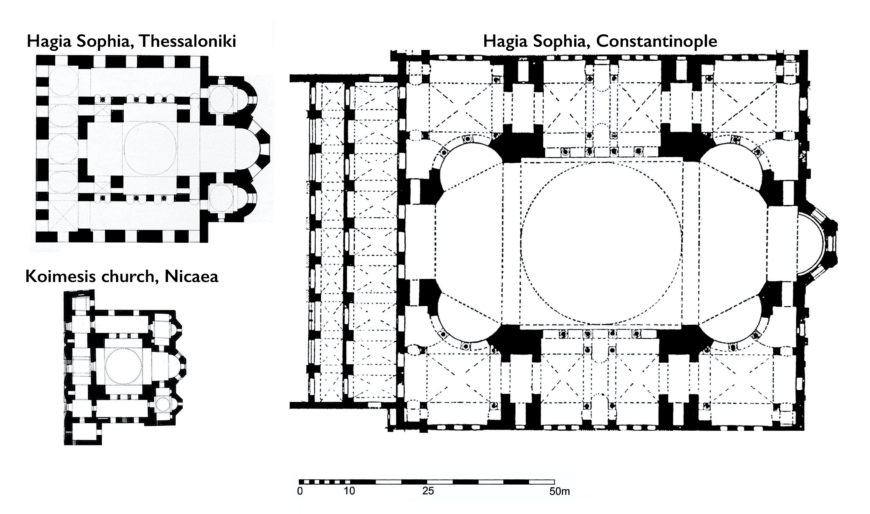

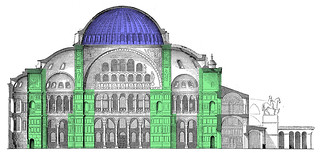

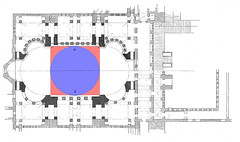

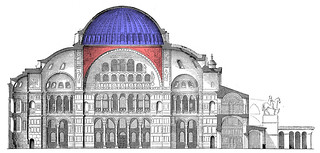

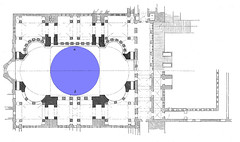

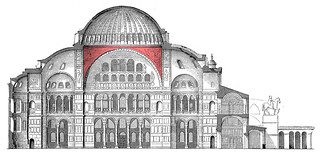

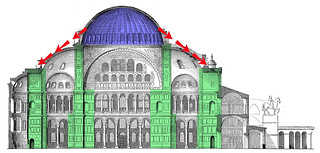

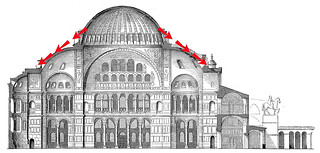

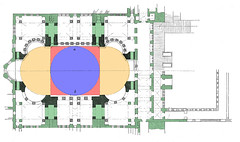

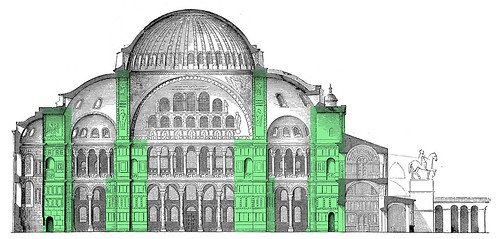

Several monumental basilicas of the period included domes and vaulting throughout, most notably at Hagia Sophia, built 532-37 by the mechanikoi Anthemios and Isidoros, which combines elements of the central plan and the basilica on an unprecedented scale.

Its unique design focused on a daring central dome of slightly more than 100 feet in diameter, raised above pendentives, and braced to the east and west by half-domes. The aisles and galleries are screened by colonnades (rows of columns), with exedrae (semicircular recesses) at the corners. Following the innovative trends in Late Roman architecture, the structural system concentrates the loads at critical points, opening the walls with large windows.

With glistening marble revetments on all flat surfaces and more than seven acres of gold mosaic on the vaults, the effect was magical—whether in daylight or by candlelight, with the dome seeming to float aloft with no discernable means of support; accordingly Procopios writes that the interior impression was “altogether terrifying.”

H. Eirene, Constantinople

Related to H. Sophia are the domed basilicas of H. Eirene in Constantinople, begun 532, and ruined Basilica ‘B’ in Philippi (Greece), built before 540, each with distinctive elements to its design. The common feature in all three buildings was an elongated nave, partially covered by a dome on pendentives, but lacking necessary lateral buttressing. All three buildings suffered partial or complete collapse in subsequent earthquakes. Read about the redesign of H. Eirene after its collapse.

Hagia Sophia’s new dome

At H. Sophia, textual accounts suggest that the first dome, which fell in 557, was a structurally daring, shallow pendentive dome, in which the curvature continued from the pendentives, but with a ring of windows at its base.

A more stable, hemispherical dome replaced the original – essentially that which survives today, with partial collapses and repairs in the west and east quadrants in the tenth and fourteenth centuries.

Although H. Polyeuktos, built in Constantinople by Justinian’s rival Juliana Anicia, is normally reconstructed as a domed basilica – and thus suggested to be the forerunner of H. Sophia, it was unlikely domed, although it was certainly its predecessor in lavishness.

Five-domed churches

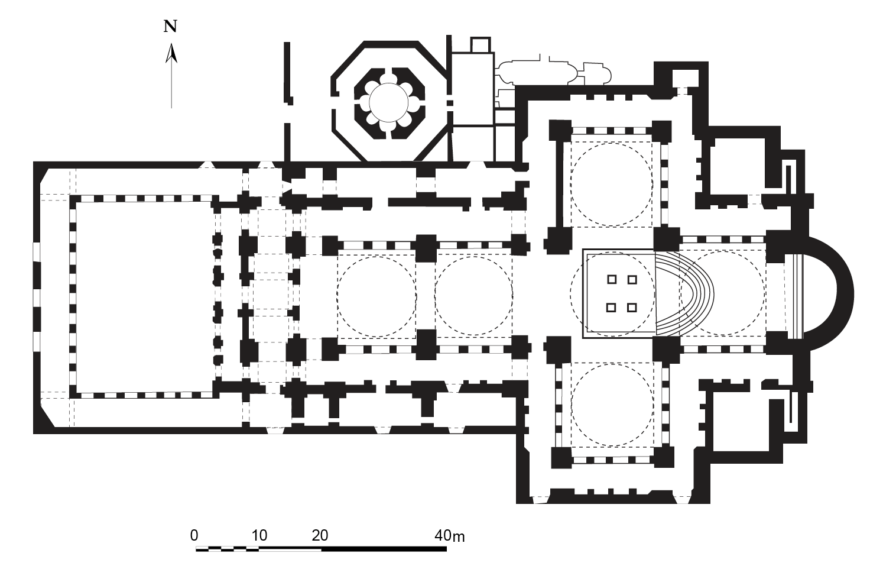

The spatial unit formed by the dome on pendentives could also be used as a design module, as at Justinian’s rebuilding of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, in which five domes covered the cruciform building.

A similar design was employed in the rebuilding of St. John’s basilica at Ephesus, completed before 565, which because of its elongated nave took on a six-domed design.

The late eleventh-century S. Marco in Venice follows this sixth-century scheme.

The enduring basilica

In spite of design innovations, traditional architecture continued in the sixth century with the wooden roofed basilica continuing as the standard church type.

At St. Catherine’s on Mt. Sinai, built c. 540, the church preserves its wooden roof and much of its decoration. The three-aisled plan incorporated numerous subsidiary chapels flanking the aisles.

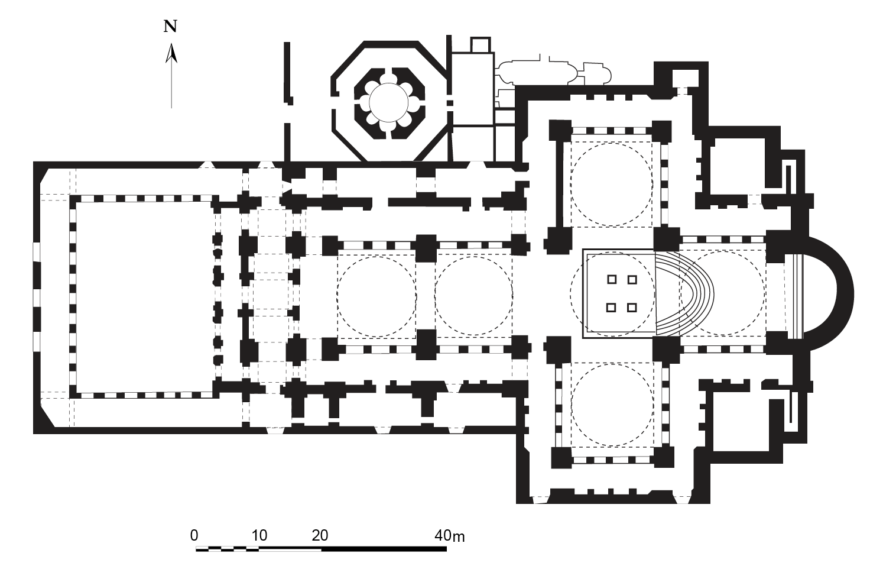

At the sixth-century Cathedral of Caricin Grad, the three-aisled basilica included a vaulted sanctuary area, with the earliest securely dated example of pastophoria: apsed chapels—known as the prothesis and diakonikon—which flanked the central altar area to form a tripartite sanctuary. This tripartite form that would become standard in later centuries.

Justinian’s legacy

Church types of the subsequent period tend to follow in simplified form the grand developments of the age of Justinian. H. Sophia in Thessalonikie for example, built less than a century later than its namesake, is both considerably smaller and heavier, as is the Koimesis church at Nicaea.

Both correct the basic problems in the structural design by including broad arches to brace the dome on all four sides.

The Caucasus

In the Caucasus, Georgia and Armenia witness a flourishing of architecture in the seventh century, with numerous, distinctive, centrally planned, domed buildings, constructed of rubble faced with a fine ashlar, although their relationship with Byzantine architectural developments remains to be clarified.

The domed church of St. Hripsime at Vagarshapat has a dome rising above eight supports, set within a rectangular building.

The church at Church of the Cross at Jvari (Mtskheta) is similar, but with its lateral apses projecting. The aisled tetraconch church of Zvartnots stands out as following Byzantine, particularly Syrian, models.

Additional Resources

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles (architects), Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 532-37

A symbol of Byzantium

The great church of the Byzantine capital Constantinople (Istanbul) took its current structural form under the direction of the Emperor Justinian I. The church was dedicated in 537, amid great ceremony and the pride of the emperor (who was sometimes said to have seen the completed building in a dream). The daring engineering feats of the building are well known. Numerous medieval travelers praise the size and embellishment of the church. Tales abound of miracles associated with the church. Hagia Sophia is the symbol of Byzantium in the same way that the Parthenon embodies Classical Greece or the Eiffel Tower typifies Paris.

Each of those structures express values and beliefs: perfect proportion, industrial confidence, a unique spirituality. By overall impression and attention to detail, the builders of Hagia Sophia left the world a mystical building. The fabric of the building denies that it can stand by its construction alone. Hagia Sophia’s being seems to cry out for an other-worldly explanation of why it stands because much within the building seems dematerialized, an impression that must have been very real in the perception of the medieval faithful. The dematerialization can be seen in as small a detail as a column capital or in the building’s dominant feature, its dome.

Let us start with a look at a column capital

The capital is a derivative of the Classical Ionic order via the variations of the Roman composite capital and Byzantine invention. Shrunken volutes appear at the corners decorative detailing runs the circuit of lower regions of the capital. The column capital does important work, providing transition from what it supports to the round column beneath. What we see here is decoration that makes the capital appear light, even insubstantial. The whole appears more as filigree work than as robust stone capable of supporting enormous weight to the column.

Compare the Hagia Sophia capital with a Classical Greek Ionic capital, this one from the Greek Erechtheum on the Acropolis, Athens. The capital has abundant decoration but the treatment does not diminish the work performed by the capital. The lines between the two spirals dip, suggesting the weight carried while the spirals seem to show a pent-up energy that pushes the capital up to meet the entablature, the weight it holds. The capital is a working member and its design expresses the working in an elegant way.

The relationship between the two is similar to the evolution of the antique to the medieval seen in the mosaics of San Vitale. A capital fragment on the grounds of Hagia Sophia illustrates the carving technique. The stone is deeply drilled, creating shadows behind the vegetative decoration. The capital surface appears thin. The capital contradicts its task rather than expressing it.

This deep carving appears throughout Hagia Sophia’s capitals, spandrels, and entablatures. Everywhere we look stone visually denying its ability to do the work that it must do. The important point is that the decoration suggests that something other than sound building technique must be at work in holding up the building.

A golden dome suspended from heaven

We know that the faithful attributed the structural success of Hagia Sophia to divine intervention. Nothing is more illustrative of the attitude than descriptions of the dome of Hagia Sophia. Procopius, biographer of the Emperor Justinian and author of a book on the buildings of Justinian is the first to assert that the dome hovered over the building by divine intervention.

“…the huge spherical dome [makes] the structure exceptionally beautiful. Yet it seems not to rest upon solid masonry, but to cover the space with its golden dome suspended from Heaven.” (from “The Buildings” by Procopius, Loeb Classical Library, 1940, online at the University of Chicago Penelope project)

The description became part of the lore of the great church and is repeated again and again over the centuries. A look at the base of the dome helps explain the descriptions.

The windows at the bottom of the dome are closely spaced, visually asserting that the base of the dome is insubstantial and hardly touching the building itself. The building planners did more than squeeze the windows together, they also lined the jambs or sides of the windows with gold mosaic. As light hits the gold it bounces around the openings and eats away at the structure and makes room for the imagination to see a floating dome.

It would be difficult not to accept the fabric as consciously constructed to present a building that is dematerialized by common constructional expectation. Perception outweighs clinical explanation. To the faithful of Constantinople and its visitors, the building used divine intervention to do what otherwise would appear to be impossible. Perception supplies its own explanation: the dome is suspended from heaven by an invisible chain.

Advice from an angel?

An old story about Hagia Sophia, a story that comes down in several versions, is a pointed explanation of the miracle of the church. So goes the story: A youngster was among the craftsmen doing the construction. Realizing a problem with continuing work, the crew left the church to seek help (some versions say they sought help from the Imperial Palace). The youngster was left to guard the tools while the workmen were away. A figure appeared inside the building and told the boy the solution to the problem and told the boy to go to the workmen with the solution. Reassuring the boy that he, the figure, would stay and guard the tools until the boy returned, the boy set off. The solution that the boy delivered was so ingenious that the assembled problem solvers realized that the mysterious figure was no ordinary man but a divine presence, likely an angel. The boy was sent away and was never allowed to return to the capital. Thus the divine presence had to remain inside the great church by virtue of his promise and presumably is still there. Any doubt about the steadfastness of Hagia Sophia could hardly stand in the face of the fact that a divine guardian watches over the church.*

Damage and repairs

Hagia Sophia sits astride an earthquake fault. The building was severely damaged by three quakes during its early history. Extensive repairs were required. Despite the repairs, one assumes that the city saw the survival of the church, amid city rubble, as yet another indication of divine guardianship of the church.

Extensive repair and restoration are ongoing in the modern period. We likely pride ourselves on the ability of modern engineering to compensate for daring 6th Century building technique. Both ages have their belief systems and we are understandably certain of the rightness of our modern approach to care of the great monument. But we must also know that we would be lesser if we did not contemplate with some admiration the structural belief system of the Byzantine Age.

*Helen C. Evans, Ph.D., “Byzantium Revisited: The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia in the Twentieth Century,” Fourth Annual Pallas Lecture (University of Michigan, 2006).

Historical outline: Isidore and Anthemius replaced the original 4th-century church commissioned by Emperor Constantine and a 5th-century structure that was destroyed during the Nika revolt of 532. The present Hagia Sophia or the Church of Holy Wisdom became a mosque in 1453 following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans under Sultan Mehmed II. In 1934, Atatürk, founder of Modern Turkey, converted the mosque into a museum.

Additional resources:

Hagia Sophia on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (Italy)

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

San Vitale and the Justinian Mosaic

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): San Vitale, begun c. 526-527, consecrated 547, Ravenna (Italy)

San Vitale is one of the most important surviving examples of Byzantine architecture and mosaic work. It was begun in 526 or 527 under Ostrogothic rule. It was consecrated in 547 and completed soon after.

One of the most famous images of political authority from the Middle Ages is the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian and his court in the sanctuary of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. This image is an integral part of a much larger mosaic program in the chancel (the space around the altar).

A major theme of this mosaic program is the authority of the emperor in the Christian plan of history.

The mosaic program can also be seen to give visual testament to the two major ambitions of Justinian’s reign: as heir to the tradition of Roman Emperors, Justinian sought to restore the territorial boundaries of the Empire. As the Christian Emperor, he saw himself as the defender of the faith. As such it was his duty to establish religious uniformity or Orthodoxy throughout the Empire.

Who’s Who in the Mosaic and What They Carry

In the chancel mosaic Justinian is posed frontally in the center. He is haloed and wears a crown and a purple imperial robe. He is flanked by members of the clergy on his left with the most prominent figure the Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna being labelled with an inscription. To Justinian’s right appear members of the imperial administration identified by the purple stripe, and at the very far left side of the mosaic appears a group of soldiers.

This mosaic thus establishes the central position of the Emperor between the power of the church and the power of the imperial administration and military.Like the Roman Emperors of the past, Justinian has religious, administrative, and military authority.

The clergy and Justinian carry in sequence from right to left a censer, the gospel book, the cross, and the bowl for the bread of the Eucharist. This identifies the mosaic as the so-called Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist.

Justinian’s gesture of carrying the bowl with the bread of the Eucharist can be seen as an act of homage to the True King who appears in the adjacent apse mosaic (image left).

Christ, dressed in imperial purple and seated on an orb signifying universal dominion, offers the crown of martyrdom to St. Vitale, but the same gesture can be seen as offering the crown to Justinian in the mosaic below. Justinian is thus Christ’s vice-regent on earth, and his army is actually the army of Christ as signified by the Chi-Rho on the shield.

Who’s in Front?

Closer examination of the Justinian mosaic reveals an ambiguity in the positioning of the figures of Justinian and the Bishop Maximianus. Overlapping suggests that Justinian is the closest figure to the viewer, but when the positioning of the figures on the picture plane is considered, it is evident that Maximianus’s feet are lower on the picture plane which suggests that he is closer to the viewer. This can perhaps be seen as an indication of the tension between the authority of the Emperor and the church.

Additional resources:

360 view of the apse (Columbia University)

360 view from the nave (Columbia University)

Nazanin Hedayat Munroe, Dress Styles in the Mosaics of San Vitale

Sarah E. Bassett, Style and Meaning in the Imperial Panels at San Vitale

Mosaics of San Vitale in Ravenna by Dr. Allen Farber

Byzantium on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

360-degree Panorama of the Apse of San Vitale from Columbia University

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

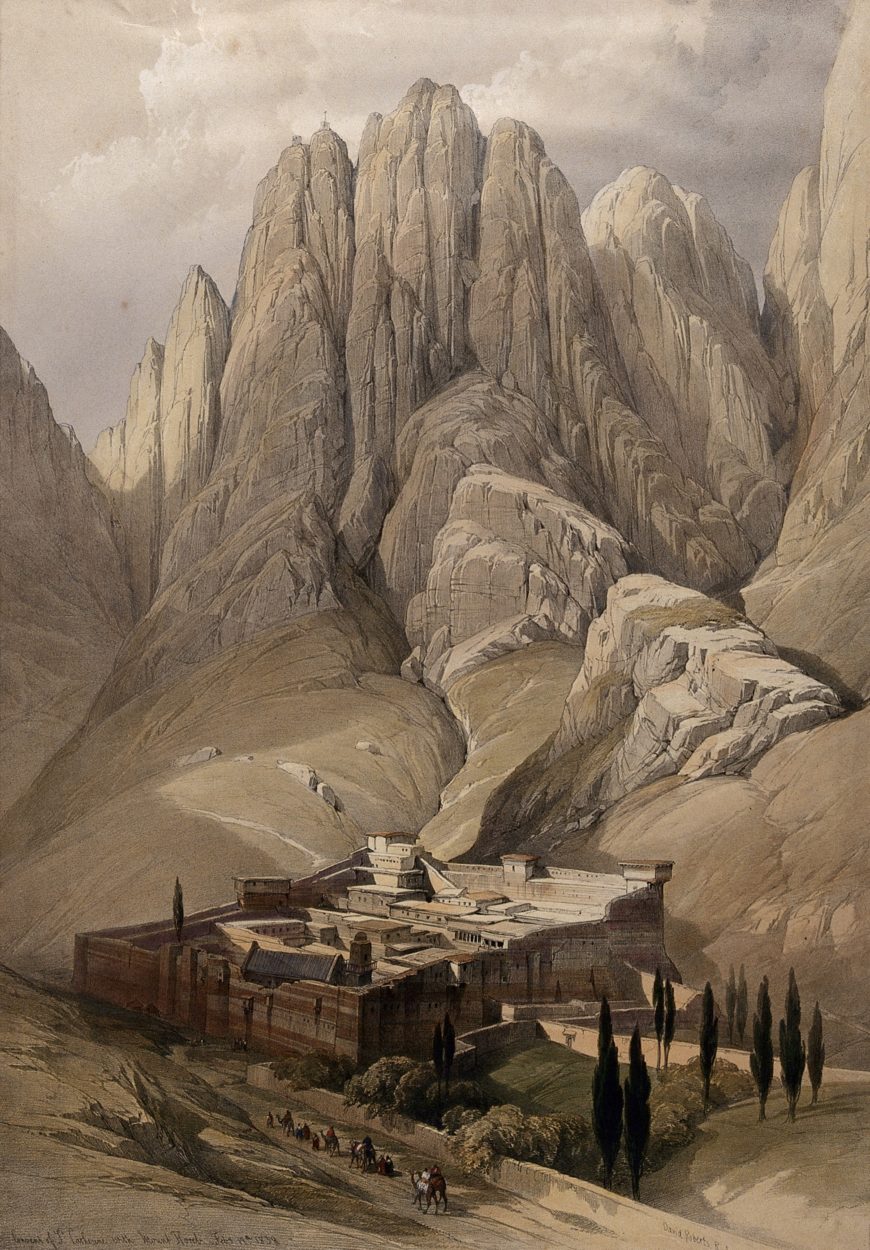

Art and architecture of Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai

A monastery built on holy ground

The Monastery of Saint Catherine is the oldest active Eastern Orthodox monastery in the world, renowned for its extraordinary holdings of Byzantine art.

The location of the monastery is significant for Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, because tradition identifies it as the place of the Burning Bush, a major biblical event where Moses encountered God:

Moses was keeping the flock of his father-in-law Jethro, the priest of Midian; he led his flock beyond the wilderness, and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed. Then Moses said, “I must turn aside and look at this great sight, and see why the bush is not burned up.” When the Lord saw that he had turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!” And he said, “Here I am.” Then he said, “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” He said further, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God.

The episode is represented in several artworks in the monastery’s collection, including an early thirteenth-century icon made of tempera and gold on wood. This image represents the moment when God spoke to Moses: “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5, NRSV).

The Monastery of Saint Catherine was founded between 548–565 C.E., in the later years of the Byzantine emperor Justinian’s reign, part of a massive building program that he had initiated across the empire.

The basilica

The monastery’s exterior walls and main church, which pilgrims can still see today, largely survive from the original, sixth-century phase of construction. A few elements came later (for example, the belfry was added in the 19th century).

Transfiguration mosaic

The church follows the pattern of a basilica, having a rectangular plan (read more about basilica churches). Monks have worshipped for 1,400 years inside this church.

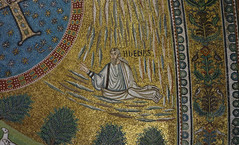

Columns frame the central nave and above the altar is a recently-restored apse mosaic that might hint at the building’s original name. The mosaic depicts a moment in the Christian New Testament called the “Transfiguration,” in which Christ appears transformed by radiant light, an event witnessed by three of his apostles. The scene is set against a glimmering gold background. When the monastery was first built it might have been dedicated to the Transfiguration, which in Christian belief is like the Burning Bush in that it is a moment when God revealed himself to humanity.

Jesus took with him Peter and James and his brother John and led them up a high mountain, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became dazzling white. Suddenly there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him…While he was still speaking, suddenly a bright cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud a voice said, “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” When the disciples heard this, they fell to the ground and were overcome by fear.

Renaming

Later, in the 9th century, when the body of the revered Egyptian Saint Catherine of Alexandria was discovered, the monastery was given the name that it has kept until today.

Icons and Iconoclasm

During the Iconoclastic period of the eighth to ninth centuries, the Byzantine Empire, and particularly its capital city of Constantinople (modern Istanbul), was convulsed with the question of whether religious images with human figures (called “icons”) were appropriate, or whether such images were in effect idols, akin to the statues of gods in ancient Greece and Rome. In other words, did worshippers pray through icons to the holy figure represented, or did they pray to the physical image itself? The Iconoclasts (those who opposed images) attempted to ban icons and reportedly even destroyed some.

But by the time of the Iconoclastic controversy, the Sinai Peninsula, where Saint Catherine’s Monastery is located, was under Islamic rather than Byzantine control, enabling the monastery’s icons to escape Iconoclasm. Other factors, including the monastery’s isolated location, fortifications, continuous occupation by monks, as well as the dry climate of the region, all likely contributed to the preservation of icons at Sinai.

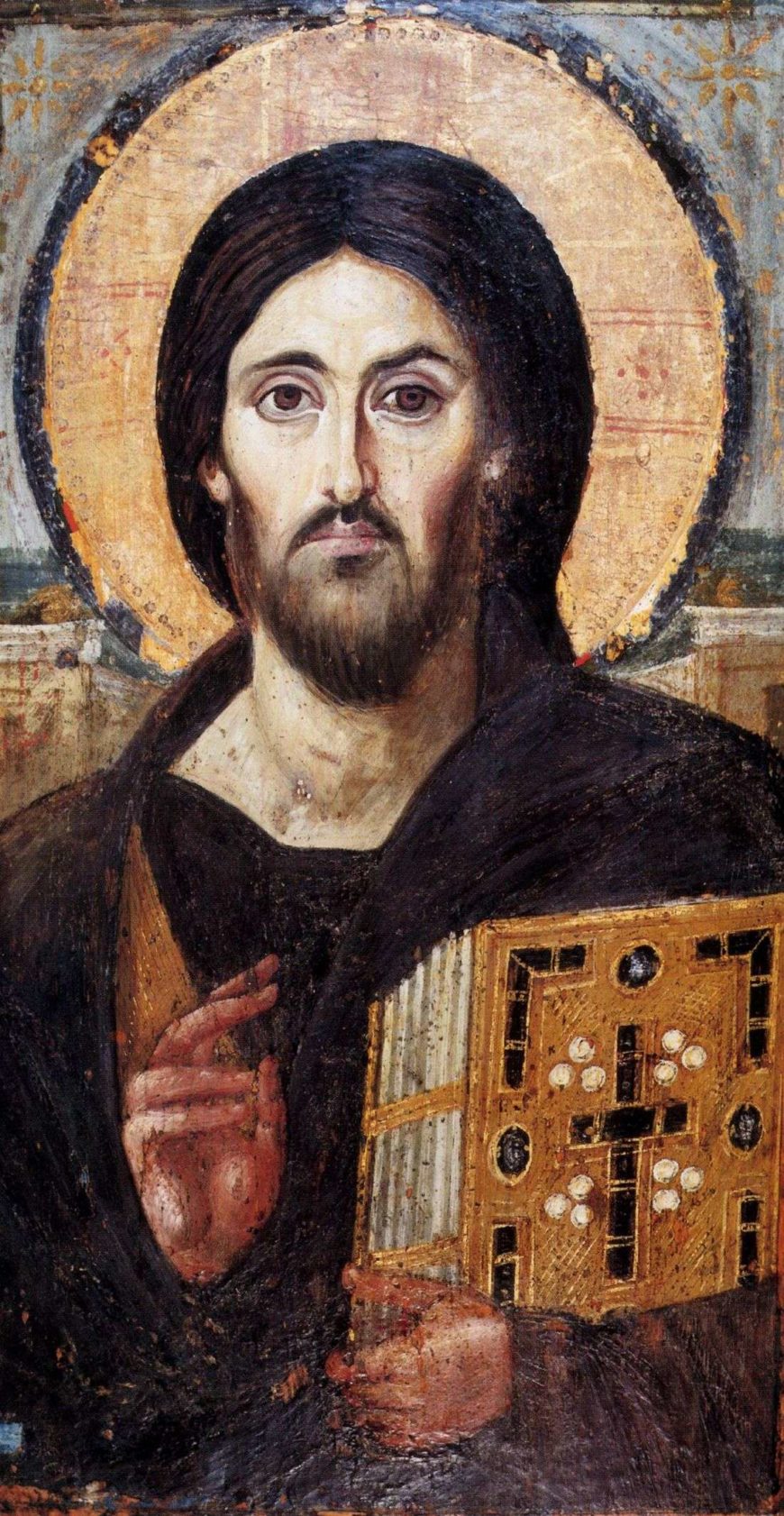

Early Byzantine Icons

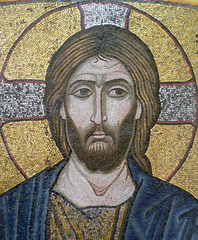

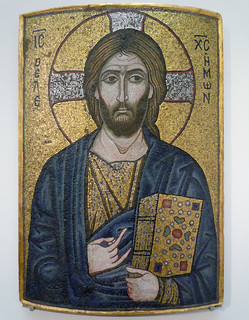

The sixth-century icon of Christ Blessing—or Christ “Pantokrator” (all-ruler), as this image would later become known—was painted using encaustic that enabled the artist to create a vivid sense of naturalism. This icon was painted by a highly skilled artist, and therefore might have been made in the capital city of Constantinople.

Christ raises his right hand to give a blessing. His other hand holds an elaborate manuscript, which probably takes the form of a contemporary Gospel book, emphasizing Christ’s identity as the embodied “Word” of God. This bearded, mature version of Christ—just one of several ways Christ appears in art before Iconoclasm—draws on pre-Christian traditions of rendering other male divinities such as Jupiter.

The Monastery of Saint Catherine preserves a number of rare Early Byzantine icons such as this.

Read about another Early Byzantine icon at Saint Catherine’s.

Middle Byzantine Icons

After Iconoclasm, perhaps to avoid accusations of idolatry, Byzantine icons became less naturalistic. Compare this Middle Byzantine icon of the Heavenly Ladder with the Early Byzantine icon of Christ. Notice, for example, the ethereal, flat gold background in the icon of the Ladder that replaces the landscape hinted at behind the halo in the sixth-century Christ “Pantokrator.”

The Heavenly Ladder

This icon of the Heavenly Ladder was made at the monastery of Saint Catherine in the late 12th century, and illustrates the process of spiritual ascent undertaken by monastics. The icon is based on a spiritual text of the same name, written by a monk called Saint John of the Ladder, who lived c. 579–649 and was a member of Saint Catherine’s Monastery. In his writing, John warns his fellow monks about temptations of the monastic life; in the icon of the Ladder, the artist depicts these temptations as elegantly silhouetted demons who attempt to tug the monks off the ladder as they climb toward Christ in the upper righthand corner.

Saint Theodosia

This 13th-century icon depicts Saint Theodosia and is one of five icons at Saint Catherine’s that depict the same saint. Clearly, Saint Theodosia’s cult was popular at Sinai as it was elsewhere in the Byzantine world.

In this image, Theodosia wears the somber dress of a nun. Although her historical status is debated (she may have been legendary rather than an actual historical figure), to the Christian faithful she represents the challenges faced during Iconoclasm, when she reputedly died defending a famed icon of Christ in Constantinople. The cross she holds represents her martyrdom. She was also famous in the late Byzantine period for healing miracles attributed to her, further enhancing her appeal for worshippers.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery today

The library of this centuries-old monastery houses many important medieval manuscripts in diverse languages such as Greek, Arabic, and Syriac. It continues to attract pilgrims from around the world—some of the current monks now in residence hail from exotic lands such as Texas.

Additional Resources

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): The Icons of Sinai, Department of Art & Archaeology, Princeton University

Robert S. Nelson and Kirsten M. Collins, eds., Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006).

Ivory Panel with Archangel

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Byzantine panel with archangel, ivory leaf from diptych, c. 525-50, 16.8 x 5.6 x 0.35″ / 42.8 x 14.3 x 0.9 cm, probably from Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey), (British Museum, London)

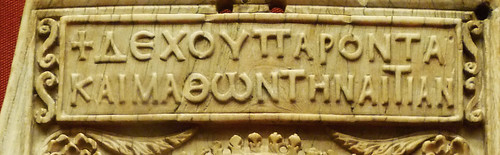

The British Museum translates the text at the top of the panel as: “Receive the suppliant before you, despite his sinfulness.”

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Emperor Triumphant (Barberini Ivory)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): The Emperor Triumphant (Barberini Ivory), mid-6th century, ivory, inlay, 34.2 x 26.8 x 2.8 (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

At Mount Sinai Monastery

One of thousands of important Byzantine images, books, and documents preserved at St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai (Egypt) is the remarkable encaustic icon painting of the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (“Icon” is Greek for “image” or “painting” and encaustic is a painting technique that uses wax as a medium to carry the color).

The icon shows the Virgin and Child flanked by two soldier saints, St. Theodore to the left and St. George at the right. Above these are two angels who gaze upward to the hand of God, from which light emanates, falling on the Virgin.

Selectively classicizing

The painter selectively used the classicizing style inherited from Rome. The faces are modeled; we see the same convincing modeling in the heads of the angels (note the muscles of the necks) and the ease with which the heads turn almost three-quarters.

The space appears compressed, almost flat, at our first encounter. Yet we find spatial recession, first in the throne of the Virgin where we glimpse part of the right side and a shadow cast by the throne; we also see a receding armrest as well as a projecting footrest. The Virgin, with a slight twist of her body, sits comfortably on the throne, leaning her body left toward the edge of the throne. The child sits on her ample lap as the mother supports him with both hands. We see the left knee of the Virgin beneath convincing drapery whose folds fall between her legs.

At the top of the painting an architectural member turns and recedes at the heads of the angels. The architecture helps to create and close off the space around the holy scene.

The composition displays a spatial ambiguity that places the scene in a world that operates differently from our world, reminiscent of the spatial ambiguity of the earlier Ivory panel with Archangel. The ambiguity allows the scene to partake of the viewer’s world but also separates the scene from the normal world.

New in our icon is what we might call a “hierarchy of bodies.” Theodore and George stand erect, feet on the ground, and gaze directly at the viewer with large, passive eyes. While looking at us they show no recognition of the viewer and appear ready to receive something from us. The saints are slightly animated by the lifting of a heel by each as though they slowly step toward us.

The Virgin averts her gaze and does not make eye contact with the viewer. The ethereal angels concentrate on the hand above. The light tones of the angels and especially the slightly transparent rendering of their halos give the two an otherworldly appearance.

Visual movement upward, toward the hand of God

This supremely composed picture gives us an unmistakable sense of visual movement inward and upward, from the saints to the Virgin and from the Virgin upward past the angels to the hand of God.

The passive saints seem to stand ready to receive the veneration of the viewer and pass it inward and upward until it reaches the most sacred realm depicted in the picture.

We can describe the differing appearances as saints who seem to inhabit a world close to our own (they alone have a ground line), the Virgin and Child who are elevated and look beyond us, and the angels who reside near the hand of God transcend our space. As the eye moves upward we pass through zones: the saints, standing on ground and therefore closest to us, and then upward and more ethereal until we reach the holiest zone, that of the hand of God. These zones of holiness suggest a cosmos of the world, earth and real people, through the Virgin, heavenly angels, and finally the hand of God. The viewer who stands before the scene make this cosmos complete, from “our earth” to heaven.

A chalice from the Attarouthi Treasure

by DR. ANNE MCCLANAN and DR. EVAN FREEMAN

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Anne and Evan discuss a Byzantine chalice (The Attarouthi Treasure — Chalice, Silver and gilded silver, 500–650 C.E., The Metropolitan Museum of Art)