6.5: Early Christian

- Page ID

- 67078

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Early Christian art

Once thought to have indicated a "decline" in artistic skill, early Christian art is now understood to represent a major shift in the way that artists and patrons visualized their beliefs and their world.

c. 200 - 500 C.E.

Early Christianity, an introduction

Key events

Two important moments played a critical role in the development of early Christianity:

- The decision of the Apostle Paul to spread Christianity beyond the Jewish communities of Palestine into the Greco-Roman world.

- When the Emperor Constantine accepted Christianity and became its patron at the beginning of the fourth century

The creation and nature of Christian art were directly impacted by these moments.

The spread of Christianity

As implicit in the names of his Epistles, Paul spread Christianity to the Greek and Roman cities of the ancient Mediterranean world. In cities like Ephesus, Corinth, Thessalonica, and Rome, Paul encountered the religious and cultural experience of the Greco Roman world. This encounter played a major role in the formation of Christianity.

Christianity as a mystery cult

Christianity in its first three centuries was one of a large number of mystery religions that flourished in the Roman world. Religion in the Roman world was divided between the public, inclusive cults of civic religions and the secretive, exclusive mystery cults. The emphasis in the civic cults was on customary practices, especially sacrifices. Since the early history of the polis or city state in Greek culture, the public cults played an important role in defining civic identity.

As it expanded and assimilated more people, Rome continued to use the public religious experience to define the identity of its citizens. The polytheism of the Romans allowed the assimilation of the gods of the people it had conquered.

Thus, when the Emperor Hadrian created the Pantheon in the early second century, the building’s dedication to all the gods signified the Roman ambition of bringing cosmos or order to the gods, just as new and foreign societies were brought into political order through the spread of Roman imperial authority. The order of Roman authority on earth is a reflection of the divine cosmos.

For most adherents of mystery cults, there was no contradiction in participating in both the public cults and a mystery cult. The different religious experiences appealed to different aspects of life. In contrast to the civic identity which was at the focus of the public cults, the mystery religions appealed to the participant’s concerns for personal salvation. The mystery cults focused on a central mystery that would only be known by those who had become initiated into the teachings of the cult.

Monotheism

These are characteristics Christianity shares with numerous other mystery cults. In early Christianity emphasis was placed on baptism, which marked the initiation of the convert into the mysteries of the faith. The Christian emphasis on the belief in salvation and an afterlife is consistent with the other mystery cults. The monotheism of Christianity, though, was a crucial difference from the other cults. The refusal of the early Christians to participate in the civic cults due to their monotheistic beliefs lead to their persecution. Christians were seen as anti-social.

Early Christian art

The beginnings of an identifiable Christian art can be traced to the end of the second century and the beginning of the third century. Considering the Old Testament prohibitions against graven images, it is important to consider why Christian art developed in the first place. The use of images will be a continuing issue in the history of Christianity. The best explanation for the emergence of Christian art in the early church is due to the important role images played in Greco-Roman culture.

As Christianity gained converts, these new Christians had been brought up on the value of images in their previous cultural experience and they wanted to continue this in their Christian experience. For example, there was a change in burial practices in the Roman world away from cremation to inhumation. Outside the city walls of Rome, adjacent to major roads, catacombs were dug into the ground to bury the dead. Families would have chambers or cubicula dug to bury their members. Wealthy Romans would also have sarcophagi or marble tombs carved for their burial. The Christian converts wanted the same things. Christian catacombs were dug frequently adjacent to non-Christian ones, and sarcophagi with Christian imagery were apparently popular with the richer Christians.

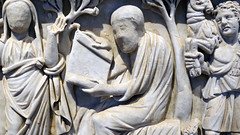

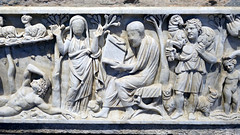

Junius Bassus, a Roman praefectus urbi or high ranking government administrator, died in 359 C.E. Scholars believe that he converted to Christianity shortly before his death accounting for the inclusion of Christ and scenes from the Bible. (Photograph above shows a plaster cast of the original.)

Themes of death and resurrection

A striking aspect of the Christian art of the third century is the absence of the imagery that will dominate later Christian art. We do not find in this early period images of the Nativity, Crucifixion, or Resurrection of Christ, for example. This absence of direct images of the life of Christ is best explained by the status of Christianity as a mystery religion. The story of the Crucifixion and Resurrection would be part of the secrets of the cult.

While not directly representing these central Christian images, the theme of death and resurrection was represented through a series of images, many of which were derived from the Old Testament that echoed the themes. For example, the story of Jonah—being swallowed by a great fish and then after spending three days and three nights in the belly of the beast is vomited out on dry ground—was seen by early Christians as an anticipation or prefiguration of the story of Christ’s own death and resurrection. Images of Jonah, along with those of Daniel in the Lion’s Den, the Three Hebrews in the Firey Furnace, Moses Striking the Rock, among others, are widely popular in the Christian art of the third century, both in paintings and on sarcophagi.

All of these can be seen to allegorically allude to the principal narratives of the life of Christ. The common subject of salvation echoes the major emphasis in the mystery religions on personal salvation. The appearance of these subjects frequently adjacent to each other in the catacombs and sarcophagi can be read as a visual litany: save me Lord as you have saved Jonah from the belly of the great fish, save me Lord as you have saved the Hebrews in the desert, save me Lord as you have saved Daniel in the Lion’s den, etc.

One can imagine that early Christians—who were rallying around the nascent religious authority of the Church against the regular threats of persecution by imperial authority—would find great meaning in the story of Moses of striking the rock to provide water for the Israelites fleeing the authority of the Pharaoh on their exodus to the Promised Land.

Christianity’s canonical texts and the New Testament

One of the major differences between Christianity and the public cults was the central role faith plays in Christianity and the importance of orthodox beliefs. The history of the early Church is marked by the struggle to establish a canonical set of texts and the establishment of orthodox doctrine.

Questions about the nature of the Trinity and Christ would continue to challenge religious authority. Within the civic cults there were no central texts and there were no orthodox doctrinal positions. The emphasis was on maintaining customary traditions. One accepted the existence of the gods, but there was no emphasis on belief in the gods.

The Christian emphasis on orthodox doctrine has its closest parallels in the Greek and Roman world to the role of philosophy. Schools of philosophy centered around the teachings or doctrines of a particular teacher. The schools of philosophy proposed specific conceptions of reality. Ancient philosophy was influential in the formation of Christian theology. For example, the opening of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the word and the word was with God…,” is unmistakably based on the idea of the “logos” going back to the philosophy of Heraclitus (ca. 535 – 475 BCE). Christian apologists like Justin Martyr writing in the second century understood Christ as the Logos or the Word of God who served as an intermediary between God and the World.

Early representations of Christ and the apostles

An early representation of Christ found in the Catacomb of Domitilla shows the figure of Christ flanked by a group of his disciples or students. Those experienced with later Christian imagery might mistake this for an image of the Last Supper, but instead this image does not tell any story. It conveys rather the idea that Christ is the true teacher.

Christ draped in classical garb holds a scroll in his left hand while his right hand is outstretched in the so-called ad locutio gesture, or the gesture of the orator. The dress, scroll, and gesture all establish the authority of Christ, who is placed in the center of his disciples. Christ is thus treated like the philosopher surrounded by his students or disciples.

Additional resources:

Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century

Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible), Yale University Open Course videos

New Testament Reading Room, Tyndale Seminary

“Shedding Light on the Catacombs of Rome,” BBC News

“From Jesus to Christ,” Frontline PBS site

“The Fathers of the Church,” biography and texts from the Catholic Encyclopedia

Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, late 2nd century – 4th century C.E.

Early Christian art and architecture after Constantine

By the beginning of the fourth century Christianity was a growing mystery religion in the cities of the Roman world. It was attracting converts from different social levels. Christian theology and art was enriched through the cultural interaction with the Greco-Roman world. But Christianity would be radically transformed through the actions of a single man.

Rome becomes Christian and Constantine builds churches

In 312, the Emperor Constantine defeated his principal rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Accounts of the battle describe how Constantine saw a sign in the heavens portending his victory. Eusebius, Constantine’s principal biographer, describes the sign as the Chi Rho, the first two letters in the Greek spelling of the name Christos.

After that victory Constantine became the principal patron of Christianity. In 313 he issued the Edict of Milan which granted religious toleration. Although Christianity would not become the official religion of Rome until the end of the fourth century, Constantine’s imperial sanction of Christianity transformed its status and nature. Neither imperial Rome or Christianity would be the same after this moment. Rome would become Christian, and Christianity would take on the aura of imperial Rome.

The transformation of Christianity is dramatically evident in a comparison between the architecture of the pre-Constantinian church and that of the Constantinian and post-Constantinian church. During the pre-Constantinian period, there was not much that distinguished the Christian churches from typical domestic architecture. A striking example of this is presented by a Christian community house, from the Syrian town of Dura-Europos. Here a typical home has been adapted to the needs of the congregation. A wall was taken down to combine two rooms: this was undoubtedly the room for services. It is significant that the most elaborate aspect of the house is the room designed as a baptistry. This reflects the importance of the sacrament of Baptism to initiate new members into the mysteries of the faith. Otherwise this building would not stand out from the other houses. This domestic architecture obviously would not meet the needs of Constantine’s architects.

Emperors for centuries had been responsible for the construction of temples throughout the Roman Empire. We have already observed the role of the public cults in defining one’s civic identity, and Emperors understood the construction of temples as testament to their pietas, or respect for the customary religious practices and traditions. So it was natural for Constantine to want to construct edifices in honor of Christianity. He built churches in Rome including the Church of St. Peter, he built churches in the Holy Land, most notably the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, and he built churches in his newly-constructed capital of Constantinople.

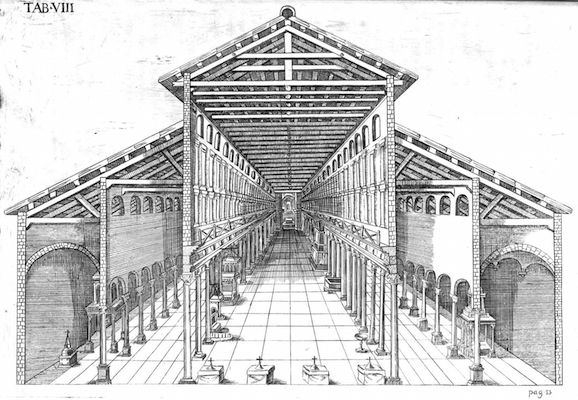

The basilica

In creating these churches, Constantine and his architects confronted a major challenge: what should be the physical form of the church? Clearly the traditional form of the Roman temple would be inappropriate both from associations with pagan cults but also from the difference in function. Temples served as treasuries and dwellings for the cult; sacrifices occurred on outdoor altars with the temple as a backdrop. This meant that Roman temple architecture was largely an architecture of the exterior. Since Christianity was a mystery religion that demanded initiation to participate in religious practices, Christian architecture put greater emphasis on the interior. The Christian churches needed large interior spaces to house the growing congregations and to mark the clear separation of the faithful from the unfaithful. At the same time, the new Christian churches needed to be visually meaningful. The buildings needed to convey the new authority of Christianity. These factors were instrumental in the formulation during the Constantinian period of an architectural form that would become the core of Christian architecture to our own time: the Christian Basilica.

The basilica was not a new architectural form. The Romans had been building basilicas in their cities and as part of palace complexes for centuries. A particularly lavish one was the so-called Basilica Ulpia constructed as part of the Forum of the Emperor Trajan in the early second century. Basilicas had diverse functions but essentially they served as formal public meeting places. One of the major functions of the basilicas was as a site for law courts. These were housed in an architectural form known as the apse. In the Basilica Ulpia, these semi-circular forms project from either end of the building, but in some cases, the apses would project off of the length of the building. The magistrate who served as the representative of the authority of the Emperor would sit in a formal throne in the apse and issue his judgments. This function gave an aura of political authority to the basilicas.

The basilica at Trier (Aula Palatina)

Basilicas also served as audience halls as a part of imperial palaces. A well-preserved example is found in the northern German town of Trier. Constantine built a basilica as part of a palace complex in Trier which served as his northern capital. Although a fairly simple architectural form and now stripped of its original interior decoration, the basilica must have been an imposing stage for the emperor. Imagine the emperor dressed in imperial regalia marching up the central axis as he makes his dramatic adventus or entrance along with other members of his court. This space would have humbled an emissary who approached the enthroned emperor seated in the apse.

Santa Maria Antiqua

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus (Sarcophagus with philosopher, orant, and Old and New Testament scenes), c. 270 C.E., marble, 23 1/4 x 86 inches (Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Early Christian and Roman (pagan) art

This third century sarcophagus from the Church of Santa Maria was undoubtedly made to serve as the tomb of a relatively prosperous third century Christian. As we will see below, Early Christian art borrowed many forms from pagan art.

The male philosopher type that we see in the center of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus (above) is easily identifiable with the same type in another third century sarcophagus (below), but in this case a non-Christian one.

The female figure beside him in the Santa Maria Antiqua sarcophagus who holds her arms outstretched combines two different conventions. The outstretched hands in Early Christian art represent the so-called “orant” or praying figure. This is the same gesture found in the catacomb paintings of Jonah being vomited from the great fish, the Hebrews in the Furnace, and Daniel in the Lions den.

The juxtaposition of this female figure with the philosopher figure associates her with the convention of the muse in ancient Greek and Roman art (as a source of inspiration for the philosopher). This convention is illustrated in a later sixth century miniature showing the figure of Dioscorides, an ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist (left).

On the left side of the sarcophagus (below), Jonah is represented sleeping under the ivy after being vomited from the great fish. The pose of the reclining Jonah with his arm over his head is based on the mythological figure of Endymion, whose wish to sleep for ever—and thus become ageless and immortal—explains the popularity of this subject on non-Christian sarcophagi (see the detail from a Roman sarcophagus below).

Another popular Early Christian image appears on the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, known as the Good Shepherd (below). While echoing the New Testament parable of the Good Shepherd and the Psalms of David, the motif had clear parallels in Greek and Roman art, going back at least to Archaic Greek art, as exemplified by the so-called Moschophoros, or calf-bearer, from the early sixth century B.C.E. (left).

On the far right of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, we see an image of the Baptism of Christ (below). The inclusion of this relatively rare representation of Christ probably refers to the importance of the sacrament of Baptism, which signified death and rebirth into a new Christian life.

A curious detail about the male and female figures at the center of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus is that their faces are unfinished. This suggests that this tomb was not made with a specific patron in mind. Rather, it was fabricated on a speculative basis, with the expectation that a patron would buy it and have his—and presumably his wife’s—likenesses added. If this is true, it says a lot about the nature of the art industry and the status of Christianity at this period. To produce a sarcophagus like this meant a serious commitment on the part of the maker. The expense of the stone and the time taken to carve it were considerable. A craftsman would not have made a commitment like this without a sense of certainty that someone would purchase it.

Additional resources

Endymion Sarcophagus on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Schmid, Werner Schmid, “Finding Sanctuary: An Early Christian Wonder in the Heart of the Roman Forum,” Icon (2005), pp. 22-27.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Good Shepherd in Early Christianity

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): A conversation with Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker in front of Christ as the Good Shepherd, 300–350 C.E., marble, 39 inches high (Museo Pio Cristiano, Vatican Museums, Rome)

Santa Pudenziana

A ritual space

The opulent interior of the Constantinian basilicas would have created an effective space for increasingly elaborate rituals. Influenced by the splendor of the rituals associated with the emperor, the liturgy placed emphasis on the dramatic entrances and the stages of the rituals. For example, the introit or entrance of the priest into the church was influenced by the adventus or arrival of the emperor.

The culmination of the entrance as well as the focal point of the architecture was the apse. It was here that the sacraments would be performed, and it was here that the priest would proclaim the word. In Roman civic and imperial basilicas, the apse had been the seat of authority. In the civic basilicas this is where the magistrate would sit adjacent to an imperial image and dispense judgment. In the imperial basilicas, the emperor would be enthroned. These associations with authority made the apse a suitable stage for the Christian rituals. The priest would be like the magistrate proclaiming the word of a higher authority.

A late fourth century mosaic in the apse of the Roman church of Santa Pudenziana visualizes this. We see in this image a dramatic transformation in the conception of Christ from the pre-Constantinian period.

From teacher to God

In the Santa Pudenziana mosaic, Christ is shown in the center seated on a jewel-encrusted throne. He wears a gold toga with purple trim, both colors associated with imperial authority. His right hand is extended in the ad locutio gesture conventional in imperial representations. Holding a book in his right hand, Christ is shown proclaiming the word. This is dependent on another convention of Roman imperial art of the so-called traditio legis, or the handing down of the law. A silver plate made for the Emperor Theodosius in 388 to mark the tenth anniversary of his accession to power shows the Emperor in the center handing down the scroll of the law. Notably the Emperor Theodosius is shown with a halo much like the figure of Christ.

While the halo would become a standard convention in Christian art to demarcate sacred figures, the origins of this convention can be found in imperial representations like the image of Theodosius. Behind the figure of Christ appears an elaborate city. In the center appears a hill surmounted by a jewel-encrusted Cross. This identifies the city as Jerusalem and the hill as Golgotha, but this is not the earthly city but rather the heavenly Jerusalem. This is made clear by the four figures seen hovering in the sky around the Cross. These are identifiable as the four beasts that are described as accompanying the lamb in the Book of Revelation.

The winged man, the winged lion, the winged ox, and the eagle became in Christian art symbols for the Four Evangelists, but in the context of the Santa Pudenziana mosaic, they define the realm as outside earthly time and space or as the heavenly realm. Christ is thus represented as the ruler of the heavenly city. The cross has become a sign the triumph of Christ. This mosaic finds a clear echo in the following excerpt from the writings of the early Christian theologian, St. John Chrysostom:

You will see the king, seated on the throne of that unutterable glory, together with the angels and archangels standing beside him, as well as the countless legions of the ranks of the saints. This is how the Holy City appears….In this city is towering the wonderful and glorious sign of victory, the Cross, the victory booty of Christ, the first fruit of our human kind, the spoils of war of our king.

The language of this passage shows the unmistakable influence of the Roman emphasis on triumph. The cross is characterized as a trophy or victory monument. Christ is conceived of as a warrior king. The order of the heavenly realm is characterized as like the Roman army divided up into legions. Both the text and mosaic reflect the transformation in the conception of Christ. These document the merging of Christianity with Roman imperial authority.

It is this aura of imperial authority that distinguishes the Santa Pudenziana mosaic from the painting of Christ and his disciples from the Catacomb of Domitilla, Christ in the catacomb painting is simply a teacher, while in the mosaic Christ has been transformed into the ruler of heaven. Even his long flowing beard and hair construct Christ as being like Zeus or Jupiter. The mosaic makes clear that all authority comes from Christ. He delegates that authority to his flanking apostles. It is significant that in the Santa Pudenziana mosaic the figure of Christ is flanked by the figure of St. Paul on the left and the figure of St. Peter on the right. These are the principal apostles.

By the fourth century, it was already established that the Bishop of Rome, or the Pope, was the successor of St. Peter, the founder of the Church of Rome. Just as power descends from Christ through the apostles, so at the end of time that power will be returned to Christ. The standing female figures can be identified as personifications of the major division of Christianity between church of the Jews and that of the Gentiles. They can be seen as offering up their crowns to Christ like the 24 Elders are described as returning their crowns in the Book of Revelation.

The meaning is clear that all authority comes from Christ just as in the Missorium of Theodosius which shows the transmission of authority from the Emperor to his co-emperors. This emphasis on authority should be understood in the context of the religious debates of the period. When Constantine accepted Christianity, there was not one Christianity but a wide diversity of different versions. A central concern for Constantine was the establishment of Christian orthodoxy in order to unify the church.

Christianity underwent a fundamental transformation with its acceptance by Constantine. The imagery of Christian art before Constantine appealed to the believer’s desires for personal salvation, while the dominant themes of Christian art after Constantine emphasized the authority of Christ and His church in the world.

Just as Rome became Christian, Christianity and Christ took on the aura of Imperial Rome. A dramatic example of this is presented by a mosaic of Christ in the Archepiscopal palace in Ravenna. Here Christ is shown wearing the cuirass, or the breastplate, regularly depicted in images of Roman Emperors and generals. The staff of imperial authority has been transformed into the cross.

Additional resources:

Photographs of Santa Pudenziana at Kunsthistorie

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, marble, 359 C.E. (Treasury of Saint Peter’s Basilica)

Please note that due to photography restrictions, the images used in the video above show the plaster cast on display in the Vatican Museum. Nevertheless, the audio conversation was recorded in the treasury in Saint Peter’s Basilica, in front of the original sarcophagus.

Christianity becomes legal

By the middle of the fourth century Christianity had undergone a dramatic transformation. Before Emperor Constantine’s acceptance, Christianity had a marginal status in the Roman world. Attracting converts in the urban populations, Christianity appealed to the faithful’s desires for personal salvation; however, due to Christianity’s monotheism (which prohibited its followers from participating in the public cults), Christians suffered periodic episodes of persecution. By the middle of the fourth century, Christianity under imperial patronage had become a part of the establishment. The elite of Roman society were becoming new converts.

Such an individual was Junius Bassus. He was a member of a senatorial family. His father had held the position of Praetorian prefect, which involved administration of the Western Empire. Junius Bassus held the position of praefectus urbi for Rome. The office of urban prefect was established in the early period of Rome under the kings. It was a position held by members of the most elite families of Rome. In his role as prefect, Junius Bassus was responsible for the administration of the city of Rome. When Junius Bassus died at the age of 42 in the year 359, a sarcophagus was made for him. As recorded in an inscription on the sarcophagus now in the Vatican collection, Junius Bassus had become a convert to Christianity shortly before his death.

The birth of Christian symbolism in art

The style and iconography of this sarcophagus reflects the transformed status of Christianity. This is most evident in the image at the center of the upper register. Before the time of Constantine, the figure of Christ was rarely directly represented, but here on the Junius Bassus sarcophagus we see Christ prominently represented not in a narrative representation from the New Testament but in a formula derived from Roman Imperial art. The traditio legis (“giving of the law”) was a formula in Roman art to give visual testament to the emperor as the sole source of the law.

Already at this early period, artists had articulated identifiable formulas for representing Sts. Peter and Paul. Peter was represented with a bowl haircut and a short cropped beard, while the figure of Paul was represented with a pointed beard and usually a high forehead. In paintings, Peter has white hair and Paul’s hair is black. The early establishment of these formulas was undoubtedly a product of the doctrine of apostolic authority in the early church. Bishops claimed that their authority could be traced back to the original Twelve Apostles.

Peter and Paul held the status as the principal apostles. The Bishops of Rome have understood themselves in a direct succession back to St. Peter, the founder of the church in Rome and its first bishop. The popularity of the formula of the traditio legis in Christian art in the fourth century was due to the importance of establishing orthodox Christian doctrine.

In contrast to the established formulas for representing Sts. Peter and Paul, early Christian art reveals two competing conceptions of Christ. The youthful, beardless Christ, based on representation of Apollo, vied for dominance with the long-haired and bearded Christ, based on representations of Jupiter or Zeus.

The feet of Christ in the Junius Bassus relief rest on the head of a bearded, muscular figure, who holds a billowing veil spread over his head. This is another formula derived from Roman art. A comparable figure appears at the top of the cuirass of the Augustus of Primaporta. The figure can be identified as the figure of Caelus, or the heavens. In the context of the Augustan statue, the figure of Caelus signifies Roman authority and its rule of everything earthly, that is, under the heavens. In the Junius Bassus relief, Caelus’s position under Christ’s feet signifies that Christ is the ruler of heaven.

The lower register directly underneath depicts Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem. This image was also based on a formula derived from Roman imperial art. The adventus was a formula devised to show the triumphal arrival of the emperor with figures offering homage. A relief from the reign of Marcus Aurelius (see image at near left) illustrates this formula. In including the Entry into Jerusalem, the designer of the Junius Bassus sarcophagus did not just use this to represent the New Testament story, but with the adventus iconography, this image signifies Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Whereas the traditio legis above conveys Christ’s heavenly authority, it is likely that the Entry into Jerusalem in the form of the adventus was intended to signify Christ’s earthly authority. The juxtaposition of the Christ in Majesty and the Entry into Jerusalem suggests that the planner of the sarcophagus had an intentional program in mind.

Old and New together

We can determine some intentionality in the inclusion of the Old and New Testament scenes. For example the image of Adam and Eve shown covering their nudity after the Fall was intended to refer to the doctrine of Original Sin that necessitated Christ’s entry into the world to redeem humanity through His death and resurrection. Humanity is thus in need of salvation from this world.

The inclusion of the suffering of Job on the left hand side of the lower register conveyed the meaning how even the righteous must suffer the discomforts and pains of this life. Job is saved only by his unbroken faith in God.

The scene of Daniel in the lion’s den to the right of the Entry into Jerusalem had been popular in earlier Christian art as another example of how salvation is achieved through faith in God.

Salvation is a message in the relief of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac on the left hand side of the upper register. God challenged Abraham’s faith by commanding Abraham to sacrifice his only son Isaac. At the moment when Abraham is about to carry out the sacrifice his hand is stayed by an angel. Isaac is thus saved. It is likely that the inclusion of this scene in the context of the rest of the sarcophagus had another meaning as well. The story of the father’s sacrifice of his only son was understood to refer to God’s sacrifice of his son, Christ, on the Cross. Early Christian theologians attempting to integrate the Old and New Testaments saw in Old Testament stories prefigurations or precursors of New Testament stories. Throughout Christian art the popularity of Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac is explained by its typological reference to the Crucifixion of Christ.

Martyrdom

While not showing directly the Crucifixion of Christ, the inclusion of the Judgment of Pilate in two compartments on the right hand side of the upper register is an early appearance in Christian art of a scene drawn from Christ’s Passion. The scene is based on the formula in Roman art of Justitia, illustrated here by a panel made for Marcus Aurelius. Here the emperor is shown seated on the sella curulis dispensing justice to a barbarian figure. On the sarcophagus Pilate is shown seated also on a sella curulis. The position of Pontius Pilate as the Roman prefect or governor of Judaea undoubtedly carried special meaning for Junius Bassus in his role as praefectus urbi in Rome. Junius Bassus as a senior magistrate would also be entitled to sit on a sella curulis.

Just as Christ was judged by Roman authority, Saints. Peter and Paul were martyred under Roman rule. The remaining two scenes on the sarcophagus represent Saints. Peter and Paul being led to their martyrdoms. Peter and Paul as the principal apostles of Christ are again given prominence. Their martyrdoms witness Christ’s own death. The artists seem to be making this point by the visual pairing of the scene of St. Peter being led to his matyrdom and the figure of Christ before Pilate. In both scenes the principal figure is flanked by two other figures.

The importance of Peter and Paul in Rome is made apparent in that two of the major churches that Constantine constructed in Rome were the Church of St. Peter and the Church of St. Paul Outside the Walls. The site of the Church of St. Peter has long believed to be the place of St. Peter’s burial. The basilica was constructed in an ancient cemetary. Although we can not be certain the the Junius Bassus Sarcophagus was originally intended for this site, it would make sense that a prominent Roman Christian like Junius Bassus would want to be buried in close physical proximity to the burial spot of the founder of the Church of Rome.

Competing styles

At either end of the Junius Bassus sarcophagus appear Erotes harvesting grapes and wheat. A panel with the same subject was probably a part of a pagan sarcophagus made for a child. This iconography is based on images of the seasons in Roman art. Again the artists have taken conventions from Greek and Roman art and converted it into a Christian context. The wheat and grapes of the classical motif would be understood in the Christian context as a reference to the bread and wine of the Eucharist.

While the dumpy proportions are far from the standards of classical art, the style of the relief especially with the rich folds of drapery and soft facial features can be seen as classic or alluding to the classical style. Comparably the division of the relief into different registers and further subdivided by an architectural framework alludes to the orderly disposition of classical art. This choice of a style that alludes to classical art was undoubtedly intentional. The art of the period is marked by a number of competing styles. Just as rhetoricians were taught at this period to adjust their oratorical style to the intended audience, the choice of the classical style was seen as an indication of the high social status of the patron, Junius Bassus. In a similar way, the representation of the figures in togas was intentional. In Roman art, the toga was traditionally used as a symbol of high social status.

In both its style and iconography, the Junius Bassus Sarcophagus witnesses the adoption of the tradition of Greek and Roman art by Christian artists. Works like this were appealing to patrons like Junius Bassus who were a part of the upper level of Roman society. Christian art did not reject the classical tradition: rather, the classical tradition will be a reoccurring element in Christian art throughout the Middle Ages.

Additional resources:

Roman Sarcophagi on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Basilica of Santa Sabina, Rome

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Basilica of Santa Sabina, 422-432, Rome

Basilicas—a type of building used by the ancient Romans for diverse functions including as a site for law courts—is the category of building that Constantine’s architects adapted to serve as the basis for the new churches. The original Constantinian buildings are now known only in plan, but an examination of a still extant early fifth century Roman basilica, the Church of Santa Sabina, helps us to understand the essential characteristics of the early Christian basilica.

Like the Trier basilica, the Church of Santa Sabina has a dominant central axis that leads from the entrance to the apse, the site of the altar. This central space is known as the nave, and is flanked on either side by side aisles. The architecture is relatively simple with a wooden, truss roof. The wall of the nave is broken by clerestory windows that provide direct lighting in the nave. The wall does not contain the traditional classical orders articulated by columns and entablatures. Now plain, the walls apparently originally were decorated with mosaics.

This interior would have had a dramatically different effect than the classical building. As exemplified by the interior of the Pantheon constructed in the second century by the Emperor Hadrian, the wall in the classical building was broken up into different levels by the horizontals of the entablatures. The columns and pilasters form verticals that tie together the different levels. Although this decor does not physically support the load of the building, the effect is to visualize the weight of the building. The thickness of the classical decor adds solidity to the building.

In marked contrast, the nave wall of Santa Sabina has little sense of weight. The architect was particularly aware of the light effects in an interior space like this. The glass tiles of the mosaics would create a shimmering effect and the walls would appear to float. Light would have been understood as a symbol of divinity. Light was a symbol for Christ. The emphasis in this architecture is on the spiritual effect and not the physical. The opulent effect of the interior of the original Constantinian basilicas is brought out in a Spanish pilgrim’s description of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem:

The decorations are too marvelous for words. All you can see is gold, jewels and silk…You simply cannot imagine the number and sheer weight of the candles, tapers, lamps and everything else they use for the services…They are beyond description, and so is the magnificent building itself. It was built by Constantine and…was decorated with gold, mosaic, and precious marble, as much as his empire could provide.

Additional resources:

Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century (online catalogue from The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome

by RICHARD BOWEN and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, 5th century A.D.

This video was produced in cooperation with our partners at Context Travel.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

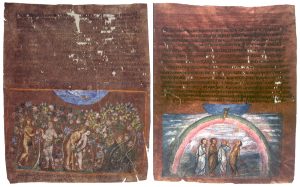

The Vienna Genesis

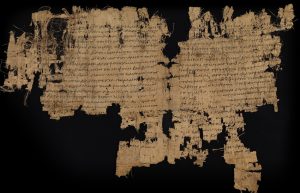

Wealthy Christian families living in the Byzantine world may have aspired to own a new kind of luxury object: the illustrated codex. Before the invention of printing in the 15th century, all texts were written or carved by hand. In the ancient world, manuscripts (texts written by hand), were found on a variety of portable surfaces. In the ancient Near East scribes wrote on clay tablets. In ancient Egypt and the ancient Greek and Roman world, information could be stored temporarily on wooden tablets coated with wax. A more lasting solution was to use scrolls made of papyrus (below): fibrous reeds that were dried in overlapping layers and then polished with a stone to create a smooth surface. Authors of papyrus scrolls usually divided their work into sections based on how much text could be held on a single scroll, leading to the concept of “chapters.”

New materials, new possibilities

All of these materials preserved texts for the few literate members of the population, but the limitations of the materials themselves made it difficult to add illustrations to the text. Papyrus scrolls were rolled for storage and then unrolled when read, causing paint to flake off. Text was scratched into the surface of a wax or clay tablet with a stylus, so only basic shapes could be created. Some time in the first or second century, however, the parchment codex (below), a more durable and flexible means of preserving and transporting text, began to replace wax tablets and papyrus scrolls. The new popularity of the codex coincided with the spread of Christianity, which required the use of texts for both the training of initiates and ritual practices.

The codex form allowed readers to find a discrete section of text quickly and to carry large amounts of text with them, which was useful for priests who traveled from place to place to serve communities of Christians. It was also essential for a religion that relied on text to establish the details of belief and set standards of conduct for its members. The vast majority of these codices were not decorated in any way, but some contained illustrations done with tempera paint that pictured events described in the text, interpreted these events, or even added visual content not found in the text.

A luxurious codex

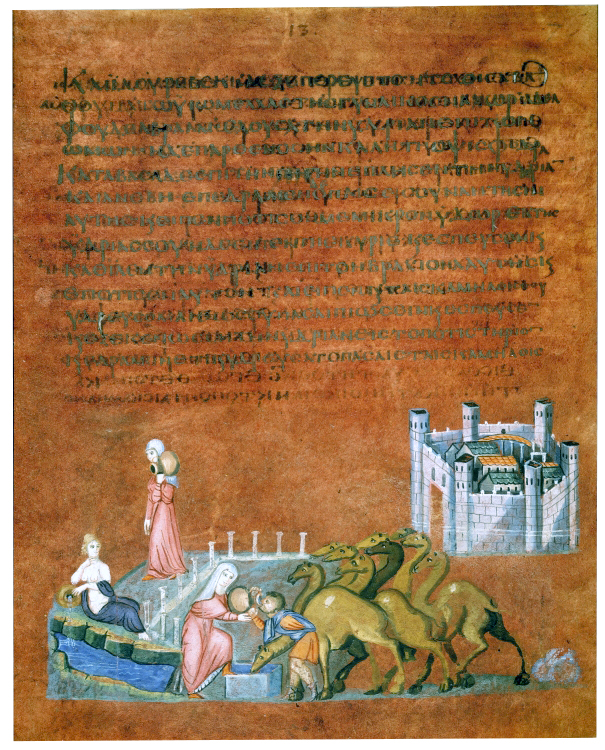

The Early Byzantine Vienna Genesis gives us a taste of what manuscripts made for a wealthy patron, likely a member of the imperial family, might have looked like. Genesis—the first book of the Christian Old Testament—described the origin of the world and the story of the earliest humans, including their first encounters with God.

The Vienna Genesis manuscript, now only partially preserved, was a very luxurious but idiosyncratic copy of a Greek translation of the original Hebrew. The heavily abbreviated text is written on purple-dyed parchment with silver ink that has now eaten through the parchment surface in many places. These materials would have been appropriate to an imperial patron, although we have no way of knowing who that was. The Vienna Genesis may have been a luxury item intended for display, or it may have provided a synopsis of exciting stories from scripture to be read for edification or diversion by a wealthy Christian.

Telling a story

The top half of each page of the Vienna Genesis is filled with text, while the bottom half contains a fully colored painting depicting some part of the Genesis story. In the scene above, Eliezer, a servant of the prophet Abraham, has arrived at a city in Mesopotamia in search of a wife for Isaac, Abraham’s son. The artist has used continuous narration, an artistic device popular with medieval artists but invented in the ancient world, wherein successive scenes are portrayed together in a single illustration, to suggest that the events illustrated happened in quick succession. In the upper right hand of the image a miniature walled city indicates that Eliezer has arrived at his destination. Rebecca, a kinswoman of Abraham, is shown twice. First, she walks down a path lined on one side with tiny spikes that symbolize a colonnaded street. Rebecca approaches a reclining, semi-nude woman who allows an overturned pot to drain into the river below. This is a personification of the river that feeds the well to the right, where Eliezer waits. Rebecca is shown a second time offering Eliezer and his camels a drink, a sign from God that she is to be Isaac’s wife.

Ancient themes, new techniques

The personification of the river reveals the image’s classical heritage, as does the use of modeling and white overpainting which lend naturalism to the garment folds and the swelling flanks of the camels.

The Vienna Genesis combines pictorial techniques familiar from the ancient world with content appropriate to a Christian audience, which is typical of Byzantine art. Though many of the details of this manuscript’s production and ownership have been lost, it remains an example of how artists combined ancient modes of expression with the most current materials and forms to create luxurious objects for wealthy patrons.

The Story of Jacob from the Vienna Genesis

by DR. NANCY ROSS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): The Story of Jacob, Vienna Genesis, folio 12v, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, cod. theol. gr. 31 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, Vienna Genesis

Caught in between

It’s not hard to find inspirational quotes about the difficulty and rewards of change and transition in our lives. There is always something old that we want to hang on to and there is always something new that we want to explore. Transitions are difficult.

The visual arts have undergone numerous changes and transitions from their prehistoric origins to the present. In Europe, artists and patrons of the ancient world loved realistic details and veracity. Medieval artists and patrons instead valued symbolism and abstraction.

The artist of the Vienna Genesis was caught between these two artistic value systems. Perhaps working in Syria or in Constantinople in the early 6th century, the artist likely did not know that this book would become the oldest surviving well-preserved illustrated biblical book and an excellent example of an artist caught in a moment of transition. The Vienna Genesis is a fragment of a Greek copy of the Book of Genesis. Books were luxury items and this book was an exceptionally fine example. It was written in silver ink on parchment that had been dyed purple, the color associated with royalty and empire. There are 24 surviving folios (pages) and they are thought to have come from a much larger book that included perhaps 192 illustrations on 96 folios, each page laid out as you can see above in the example of Rebecca and Eliezer at the well.

This story is from Genesis 24. Abraham wanted to find a wife for his son Isaac and sent his servant Eliezer to find one from among Abraham’s extended family. Eliezer took ten of Abraham’s camels with him and stopped at a well to give them water. Eliezer prayed to God that Isaac’s future wife would assist him with watering his camels. Rebecca arrives on the scene and assists Eliezer, who knows that she is the woman for Isaac. This story is about God intervening to ensure a sound marriage for Abraham’s son.

Two episodes

The illustration of this biblical story shows two episodes, which is common in medieval art. Rebecca is shown twice, as she leaves her town to get water and then assisting Eliezer at the well with his camels. On the one hand, there are clear classical elements that recall artwork from ancient Greece and Rome. Rebecca walks by a colonnade (row of columns) that recall the details of classical architecture. Some of Eliezer’s camels are shaded to emphasize that some are in the front and others in the back. The camel on the far right has one of its back legs in shadow to show a spatial relationship.

Ancient Greek and Roman, but also Early Christian

The figure that most obviously recalls the Ancient Greek and Roman world is the reclining nude next to the river (left). This figure isn’t part of the story of Rebecca and Eliezer, but serves as a personification of the source of the well’s water. Representations of rivers and other bodies of water as people were common in the classical world (see below). The figure’s sensuality is emphasized by her nudity and reclining pose, typical of Greek and Roman art. This stands in contrast to Rebecca’s heavily draped and fully-covered body, typical of Early Christian art.

There are also elements of the illustration that recall Early Christian art, which is the earliest medieval art. The symbolic representation of the walled city, packed with rooftops and buildings that are not represented in a spatially consistent way, is typical of medieval art, as is the colonnade in miniature. Medieval artists weren’t interested in realistic, consistent representations of space, but were satisfied with the more symbolic representations that we see here. The folds of the clothing are also simplified and reduced. The figures appear to be more cartoon-like than portraits of actual people.

Today, it is a struggle for us to reconcile the figures of Rebecca, who only reveals her hands and face, with the casual nude reclining by the water. This contrast is evidence of the mix of artistic models and sources that were present in the early sixth century. To the artist who illustrated this book, I’m sure that this mix of styles and approaches made perfect sense, and represented a culture in transition.

Classicism and the Early Middle Ages

In 1942 a farmer plowing a field in the East of England unearthed a substantial hoard of Roman silver dating from the fourth century, C.E. This became known as the “Mildenhall Treasure,” named for the nearby town. Its original owner may have buried his collection of banqueting vessels when the Roman administration left England in 410 C.E., hoping that he could later retrieve it. Among the spoons, bowls, dishes, and ladles is a two-foot wide silver platter weighing almost eighteen pounds, with classical motifs borrowed from antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome). However, though the platter depicts the gods Neptune and Bacchus, the owner was likely a follower of Christianity—a newly-sanctioned religion that was not yet the dominant belief system in Europe. This confluence of classical and Christian concepts is typical of the early middle ages. Because of the political and social upheavals happening in Europe at this time, the art of this period comprises a wide range of styles and themes that often blend classical elements with new and different ones.

A “decline”?

The transition between antiquity and the Middle Ages is often perceived as having been marked by a sharp break in beliefs and artistic style. This change was, in the past, characterized by scholars as a “decline.” According to this narrative, the chaotic and unstable atmosphere of the Roman Empire in the later third century led many of its inhabitants to embrace new, minority religions imported from the empire’s edges. Some of these were messianic religions that promised members an afterlife more pleasant than their current, increasingly difficult existences. At the same time, the economic struggles of the Late Roman Empire undermined investment in the artists’ workshops where the naturalism of classical Roman art had been taught to generations of artists. Lacking the traditional training, means, and patrons who valued classicism, artists during this period often worked in a more static, two-dimensional style that emphasized ideas and symbols over naturalistic illusionism. The abandonment of naturalistic style also coincided, it seemed, with the rise of a new majority religion, Christianity, that rejected materiality and traditional forms of beauty in favor of simplicity and self-denial.

Two stone reliefs installed on the Arch of Constantine demonstrate this supposed “decline.” The reused roundel with a sacrifice to Apollo (left) originally carved for a monument to the Emperor Trajan between 117 and 138 (when the Roman empire was more stable), displays many key characteristics of classicism: varied depth of relief, carefully delineated drapery folds, and figures shifting in space. By contrast, in the panel depicting the emperor distributing largesse (right), commissioned in the Late Empire between 312 and 315, the figures seem almost comically disproportionate, with enormous heads and hands, and draperies indicated by drilled lines.

The problem with the idea of a “decline” is that it ignores the many, often contradictory, currents of art and experience that existed in the late antique world. Romans had long sought to incorporate newly conquered and colonized populations by appropriating local religious beliefs and artistic traditions, in the process creating new, localized versions of Roman art that were sometimes less naturalistic. Even artists working in the capital, Rome, could choose to employ either naturalism or a more symbolic visual shorthand, depending on who made the art and who consumed it—as in the Amiternum Tomb (above), which was made during the first century, when classicism was the most prominent style. Instead of displaying a classical attention to composition, the artist has arrayed stocky figures of a variety of sizes in a seemingly haphazard way—going against the current artistic trends of the day.

Classicism survives

If works like the Amiternum Tomb help complicate the idea of an artistic decline, do they perhaps simply demonstrate variances in artists’ and patrons’ tastes? Some have argued that Emperor Constantine (who decriminalized Christianity in Rome in the early fourth century), and by extension the increasingly Christian populace, were, because of their beliefs, drawn to a non-classical style that denied naturalism in favor of a more symbolic set of forms. But surviving artworks commissioned by wealthy Romans show that, like their pagan peers, many Christians often still preferred a classicizing style—even if the subjects portrayed were new. For instance, in the middle of the fourth century the body of Junius Bassus, a Roman prefect (high official), was buried in an elaborate marble sarcophagus.

Since he was a Christian convert, Junius’s sarcophagus was covered with narrative and symbolic scenes from the Christian bible, all rendered in a classicizing style. The standing apostles are wrapped in Roman togas and the youthful Christ sits on a sella curulis, the animal-headed and -footed chair of the governing classes. Unlike most classical works, here the hands and heads of the figures are a little too large, but the artist was clearly attempting to employ the stylistic language of classicism to transmit Christian content.

These aesthetic departures from strict classicism were not limited to Christian-sponsored art: the same tendencies are apparent in objects that were commissioned by avowed pagans around the same time. This ivory panel was commissioned to celebrate a marriage between members of two Roman patrician (noble) families, the Nicomachi and Symmachi. A female figure with an oversized head and hands stands next to an altar, while a comparatively tiny servant stands behind it. The woman’s back leg projects in front of the surrounding frame, while her front leg, counterintuitively, stands on the ground within it, breaking the rules of naturalism. Based on the artworks that survive, we know that both pagan and Christian patrons found these kinds of contradictions in space and proportion acceptable.

A hoard of silver

There were also a diversity of themes preferred amongst patrons of different religions. Artworks from this time sometimes combine overtly pagan content with classicizing style, but for use by Christians. The so-called “Great Dish” found in the Mildenhall treasure is a shining example of such artistic combinations. Concentric rings of repoussé and engraved decoration celebrate the classical themes of the ocean and Bacchic revelry. The hair and beard of the Roman god Neptune in the center of the dish radiate dolphins and seaweed. Around him nymphs ride sea creatures.

In the outer band Bacchus (the god of wine), Hercules, Pan and throngs of satyrs and maenads holding Bacchic thistle-headed staffs and a shepherd’s crook twist and turn, draperies swirling, dancing with wine-induced abandon.

While this dish’s classicizing style and subject matter are undeniable, we known that its owner was likely Christian, as spoons from his dinnerware set (below) include the Christian symbols of the Chi-Rho and Alpha and Omega. Despite his Christianity, the owner likely felt perfectly comfortable displaying the platter with its exuberant dancing nudes on his sideboard for the admiration of his guests.

Rather than demonstrating a “decline” or a sharp break in artistic themes and styles, Roman artworks of the early middle ages display as much diversity and blending as the empire itself.

Additional Resources:

The Mildenhall Treasure Project at the British Museum

The Mildenhall Great Dish at the British Museum

The Symmachi Panel at the Victoria and Albert Museum

Dale Kinney and Anthony Cutler, “A Late Antique Ivory Plaque and Modern Response,” American Journal of Archaeology 98 (1994), pp. 457-480

Richard Hobbs, The Mildenhall Treasure (London: The British Museum Press, 2012)

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, 425 C.E., Ravenna (Italy)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: