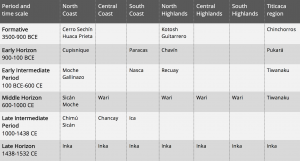

11.5: South America before c. 1500

- Page ID

- 67099

South America to c. 1500

3500 B.C.E.–1500 C.E.

Introduction to Andean Cultures

A land of contrasts

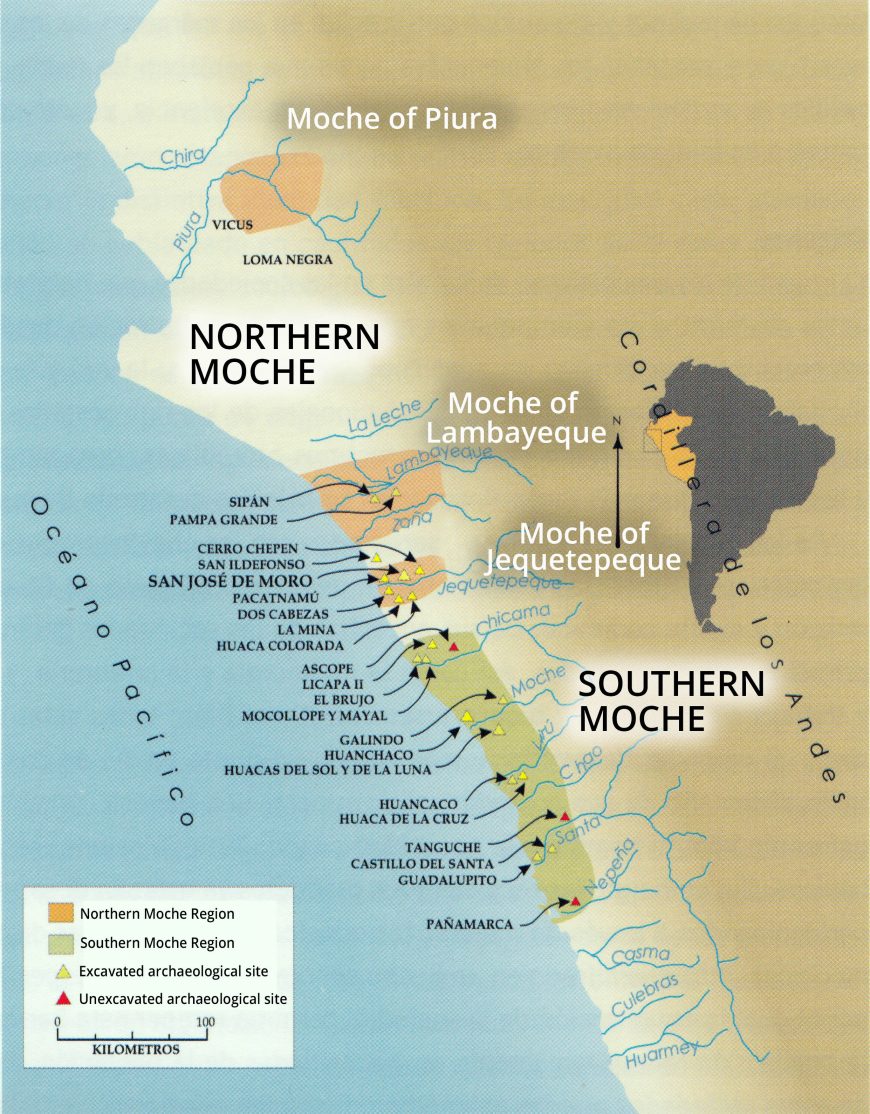

“The Andes” can refer to the mountain range that stretches along the west coast of South America, but is also used to refer to a broader geographic area that includes the coastal deserts to the west and into the tropical jungles to the east of those mountains. This region is seen as home to a distinct cultural area—dating from around the fourth millennium B.C.E. to the time of the Spanish conquest—and many of these cultures still persist today in various forms.

From the desert coast, the mountains rise up quickly, sometimes within 10-20 kilometers of the Pacific Ocean. Therefore, the people who lived in the Andes had to adapt to varying types of climate and ecosystems. This diverse environment gave rise to a range of architectural and artistic practices.

Deserts, mountains, and farms

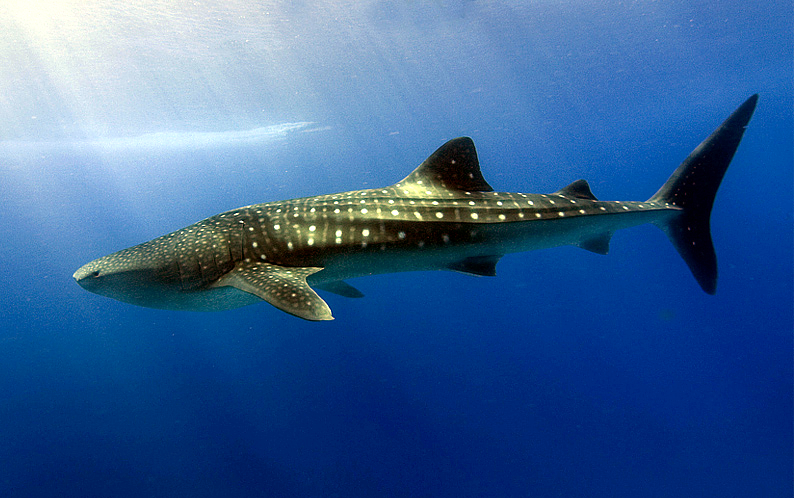

Though much of the Andean coast is near the Equator, its waters are cold, due to currents from the Antarctic. This cold water is rich in sea life; however, during El Niño years, warm water takes over, leading to large die-offs of fish and marine mammals, and often creating catastrophic flooding on the coast.

In normal years, the coast is very dry. The rivers that run to the coast, fed by melting snow from the Andes mountains (called the Cordillera Blanca, or White Mountains, in contrast to the Cordillera Negra, or Black Mountains to the west where snow does not fall), create areas of agricultural lands interspersed with desert. Cultures eventually learned to create canals, allowing them to irrigate more land, and irrigation remains important to farming on Peru’s coast.

As the elevation climbs, different ecological zones are created, and people of the Andes used these to grow different products: maize (corn), hot peppers, potatoes, and coca all grew at different elevations. Some cultures (such as the Cupisnique and Paracas) developed on the coast, and incorporated seafood into their diet. They would trade with the cultures that lived in the highlands (such as the Recuay and the inhabitants of Chavín de Huantar) for the things they could not grow for themselves. The people in the highlands would likewise trade with the coastal peoples for dried fish and products that would not grow at their elevation, as well as exotic animals like parrots from the tropical jungles to the east.

Plants and animals

The plants and animals of the Andes provided ancient peoples with food, medicine, clothing, heat, and many other resources for daily life. As noted above, the rapid change in elevation of the Andes meant that many different foods could be grown in a compressed area. Potatoes were a staple food of the highlands, and maize and manioc were important in the lower elevations.

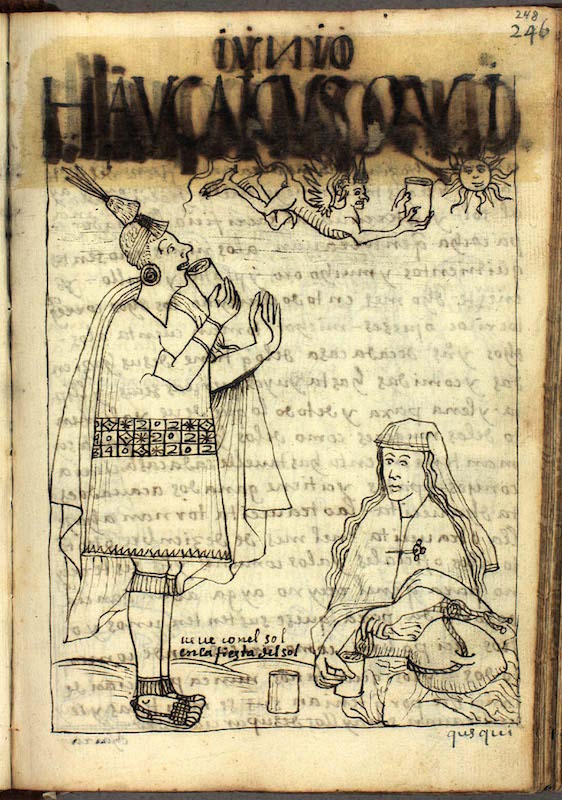

Coca grew in the highlands but was traded all over the Andes. The leaves of this plant, when chewed, provide a stimulant that allows people to walk for long periods at high altitude without getting tired, and it suppresses hunger. It was used by travelers in the highlands, but was also used in ritual practices to endure long nights of dancing. In modern times, people drink it as a tea to help with the symptoms of altitude sickness.

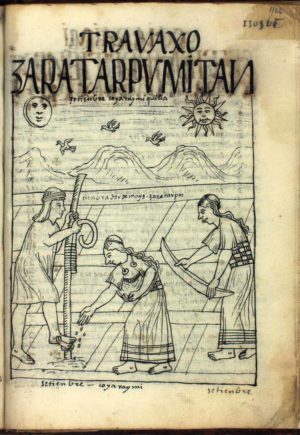

Farming in the steep topography of the mountains could be difficult, and an important innovation developed by the Andeans was the use of terracing. By creating terraces (essentially giant steps along the contours of a mountain) people were able to make flat, easily worked plots. The terraces were formed by creating retaining walls that were then backfilled with a thick layer of loose stones to aid drainage, and topped with soil.

The most important animals in the highlands were camelids: the wild vicuña and guanaco, and their domesticated relatives, the llama and alpaca. Alpacas have soft wool and were sheared to make textiles, and llamas can carry burdens over the difficult terrain of the mountains (an adult male llama can carry up to 100 pounds, but could not carry an adult human).

Both animals were also used for their meat, and their dried dung served as fuel in the high altitudes, where there was no wood to burn. Andean camelids, like their African and Asian cousins, can be very headstrong. If they are overloaded, they will sit on the ground and refuse to budge. Because of this, the ancient people of the Andes did not have domesticated animals that could carry them or pull heavy wagons, and so roads and methods of moving people and goods developed differently than in Europe, Asia, and Africa. The wheel was known, but not used for transport, because it simply would not have been useful.

Textile arts

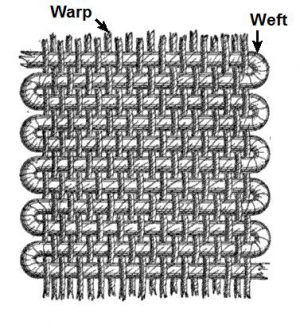

The ancient peoples of the Andes developed textile technology before ceramics or metallurgy. Textile fragments found at Guitarrero Cave date from c. 5780 B.C.E. Over the course of millennia, techniques developed from simple twining to complex woven fabrics. By the first millennium C.E., Andean weavers had developed and mastered every major technique, including double-faced cloth and lace-like open weaves.

Andean textiles were first made using fibers from reeds, but quickly moved to yarn made from cotton and camelid fibers. Cotton grows on the coast, and was cultivated by ancient Andeans in several colors, including white, several shades of brown, and a soft grayish blue. In the highlands, the alpaca provided soft, strong wool in natural colors of white, brown, and black. Both cotton and wool were also dyed to create more colors: red from cochineal, blue from indigo, and other colors from plants that grew at various elevations. Alpaca wool is much easier to dye than cotton, and so it was usually preferred for coloring. The extra time and effort needed to dye fibers made the bright colors a symbol of status and wealth throughout Andean history.

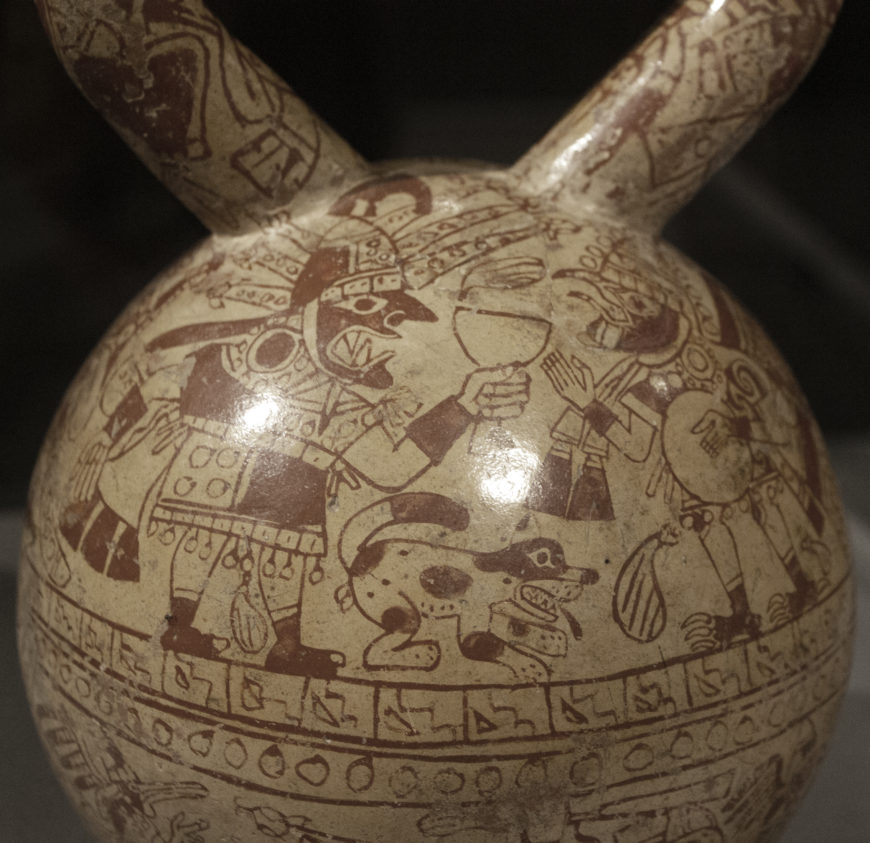

Ceramics

Though ceramics were not as valuable as textiles to Andean peoples, they were important for spreading religious ideas and showing status. People used plain everyday wares for cooking and storing foods. Elites often used finely made ceramic vessels for eating and drinking, and vessels decorated with images of gods or spiritually important creatures were kept as status symbols, or given as gifts to people of lesser status to cement their social obligations to those above them.

There are a wide variety of Andean ceramic styles, but there are some basic elements that can be found throughout the region’s history. Wares were mostly fired in an oxygenating atmosphere, resulting in ceramics that often had a red cast from the clay’s iron content. Some cultures, such as the Sicán and Chimú, instead used kilns that deprived the clay of oxygen as it fired, resulting in a surface ranging from brown to black.

Decoration of ceramics could be done by incising lines into the surface, creating textures by rocking seashells over the damp clay, or by painting the surface.

Some early elite ceramics were decorated after firing with a paint made from plant resin and mineral pigments. This produced a wide variety of bright colors, but the resin could not withstand being heated and so these resin-painted wares were only for display and ritual use. Most ceramics in the Andes instead were slip-painted. Slip is a liquid that is made of clay, and the color of the slip is determined by the color of the clay and its mineral content. Most slip painting was applied before firing, after the semi-dry clay had been burnished with a smooth stone to prepare the surface. The range of slip colors could vary from two (seen in Moche ceramics) to seven or more (seen in Nasca ceramics). Once fired, the burnished surface would be shiny. Ceramics, because of their durability, are one of the greatest resources for understanding ancient Andean cultures.

Metalwork

Metalworking developed later in Andean history, with the oldest known gold artifact dating to 2100 B.C.E., and evidence of copper smelting from around 900–700 B.C.E. Gold was used for jewelry and other forms of ornamentation, as well as for making sculptural pieces. Inka figurines of silver and gold depicting humans and llamas have been recovered from high-altitude archaeological sites in Peru and Chile. Copper and bronze were also used to create jewelry and items like ceremonial knives (called tumis).

Architecture

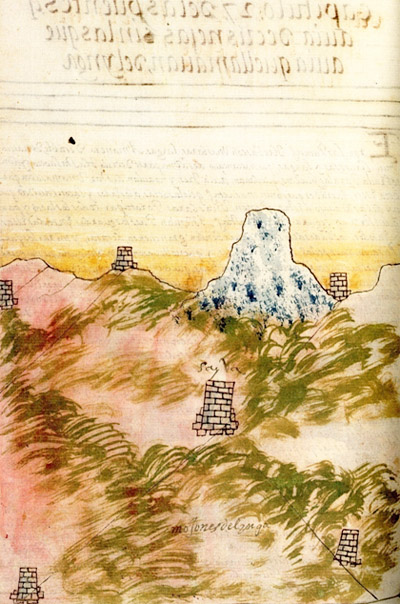

The architecture of the Andes can be divided roughly between highland and coastal traditions. Coastal cultures tended to build using adobe, while highland cultures depended more on stone. However, the lowland site of Caral, which is currently the oldest complex site known in the Andes, was built mainly using stone.

Beginning with Caral in 2800 B.C.E, various cultures constructed monumental structures such as platforms, temples, and walled compounds. These structures were the focus of political and/or religious power, like the site of Chavín de Huantár in the highlands or the Huacas de Moche on the coast. Many of these structures have been heavily damaged by time, but some reliefs and murals used to decorate them survive.

The best-known architecture in the Andes is that of the Inka. The Inka used stone for all of their important structures, and developed a technique that helped protect the structures from earthquakes. Because of its stone construction, Inka architecture has survived more easily than the adobe architecture of the coast. Ongoing efforts by archaeologists and the Peruvian Ministry of Culture are also focused on restoring and preserving the great works of coastal architecture.

Ancient past, continuing traditions

From textiles to ceramics, metalwork, and architecture, Andean cultures produced art and architecture that responded to their natural environment and reflected their beliefs and social structures. We can learn much about these ancient traditions through the artifacts and sites that survive, as well as the many ways that these practices—such as weaving—persist today.

Additional resources:

Dualism in Andean Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Chavin (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

Project page for the Huaca de la Luna restoration by the World Monuments Fund

Introduction to Ancient Andean Art

Mountain highlands to arid coastlines

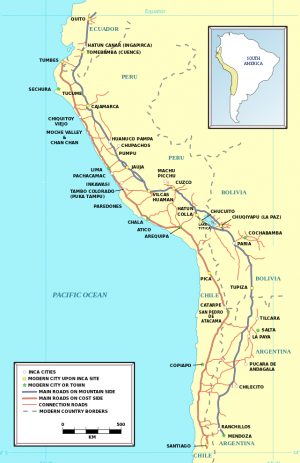

The Andes region encompasses the expansive mountain chain that runs nearly 4,500 miles north to south, covering parts of modern-day Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. The pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Andes developed a stunning visual tradition that lasted over 10,000 years before the Spanish invasion of South America in 1532.

One of the most ecologically diverse places in the world, the Andes mountains give way to arid coastlines, fertile mountain valleys, frozen highland peaks that reach as high as 22,000 feet above sea level, and tropical rainforests. These disparate geographical and ecological regions were unified by complex trade networks grounded in reciprocity.

The Andes was home to thousands of cultural groups that spoke different languages and dialects, and who ranged from nomadic hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers. As such, the artistic traditions of the Andes are highly varied.

Pre-Columbian architects of the dry coastal regions built cities out of adobe, while highland peoples excelled in stone carving to produce architectural complexes that emulated the surrounding mountainous landscape.

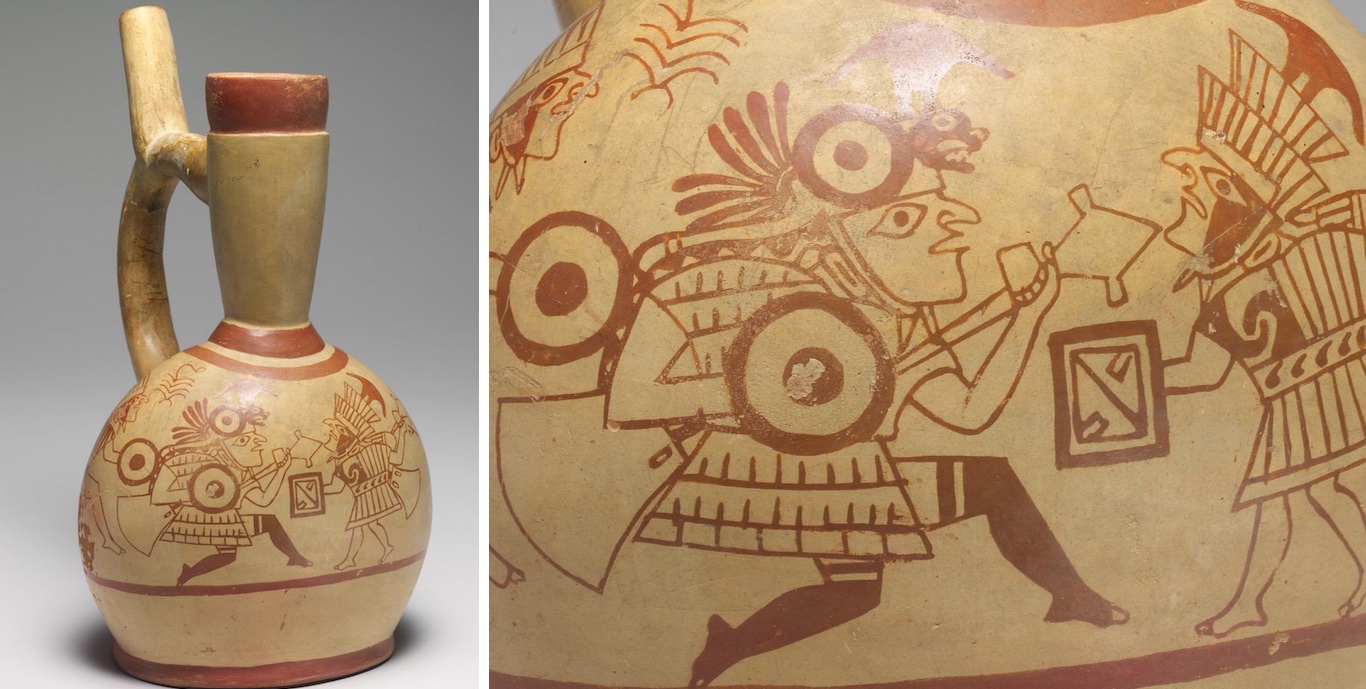

Artists crafted objects of both aesthetic and utilitarian purposes from ceramic, stone, wood, bone, gourds, feathers, and cloth. Pre-Columbian Andean peoples developed a broad stylistic vocabulary that rivaled that of other ancient civilizations in both diversity and scope. From the breathtaking naturalism of Moche anthropomorphic ceramics to the geometric abstraction found in Inka textiles, Andean art was anything but static or homogeneous.

Characteristics

While Andean art is perhaps most notable for its diversity, it also possesses many unifying characteristics. Andean artists across the South American continent often endowed their works with a life force or sense of divinity. This translated into a process-oriented artistic practice that privileged an object’s inner substance over its appearance.

Andean art is also characterized by its environmental specificity; pre-Columbian art and architecture was intimately tied to the natural environment. Textiles produced by the Paracas culture, for instance, contained vivid depictions of local birds that could be found throughout the desert peninsula.

The nearby Nazca culture is best known for its monumental earthworks in the shape of various aquatic and terrestrial animals that may have served as pilgrimage routes. The Inkas, on the other hand, produced windowed monuments whose vistas highlighted elements of the adjacent sacred landscape. Andean artists referenced, invoked, imitated, and highlighted the natural environment, using materials acquired both locally and through long-distance trade. Andean objects, images, and monuments also commanded human interaction.

Worn, touched, held, maneuvered, or ritually burned

Pre-Columbian Andean art was meant to be touched, worn, held, maneuvered, or ritually burned. Elaborately decorated ceramic pots would have been used for storing food and drink for the living or as grave goods to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. Textiles painstakingly embroidered or woven with intricate designs would have been worn by the living, wrapped around mummies, or burned as sacrifices to the gods. Decorative objects made from copper, silver, or gold adorned the bodies of rulers and elites. In other words, Andean art often possessed both an aesthetic and a functional component — the concept of “art for art’s sake” had little applicability in the pre-Columbian Andes. This is not to imply that art was not appreciated for its beauty, but rather that the process of experiencing art went beyond merely viewing it.

The supernatural

At the same time that Andean art commanded human interaction, it also resonated with the supernatural realm. Some works were never seen or used by the living. Mortuary art, for instance, was essentially created only to be buried in the ground.

The magnificent ceramics and metalwork found at the grave of the Lord of Sipán on Peru’s north coast required a tremendous output of labor, yet were never intended for living beings. The notion of “hidden” art was a convention found throughout the pre-Columbian world. In Mesoamerica, for instance, burying objects in ritual caches to venerate the earth gods was practiced from the Olmec to the Aztec civilizations.

Works of art associated with particular rituals, on the other hand, were often burned or broken in order to “release” the object’s spiritual essence. Earthworks and architectural complexes best viewed from high above would have only been “seen” from the privileged vantage point of supernatural beings. Indeed, it is only with the advent of modern technology such as aerial photography and Google Earth that we are able to view earthworks such as the Nazca lines from a “supernatural” perspective.

Art was often conceived within a dualistic context, produced for both human and divine audiences. The pre-Columbian Andean artistic traditions covered here comprise only a sampling of South America’s rich visual heritage. Nevertheless, it will provide readers with a broad understanding of the major cultures, monuments, and artworks of the Andes as well as the principal themes and critical issues associated with them.

Additional resources:

Dualism in Andean Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Music in the Ancient Andes on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Birds of the Andes on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Elizabeth Hill Boone, ed., Andean Art at Dumbarton Oaks (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1996)

Sarahh Scher and Billie J. A. Follensbee, eds., Dressing the Part: Power, Dress, Gender, and Representation in the Pre-Columbian Americas (University Press of Florida, 2017)

Rebecca Stone. Art of the Andes: from Chavín to Inca (Thames & Hudson 2012)

Cupisnique

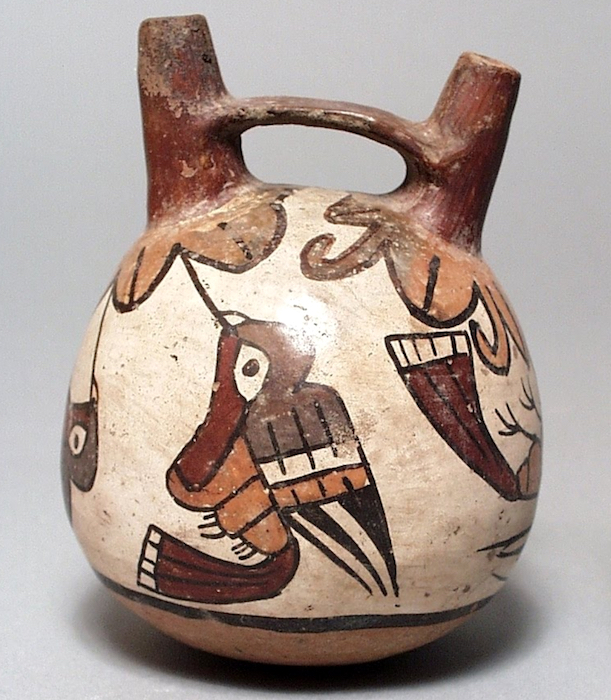

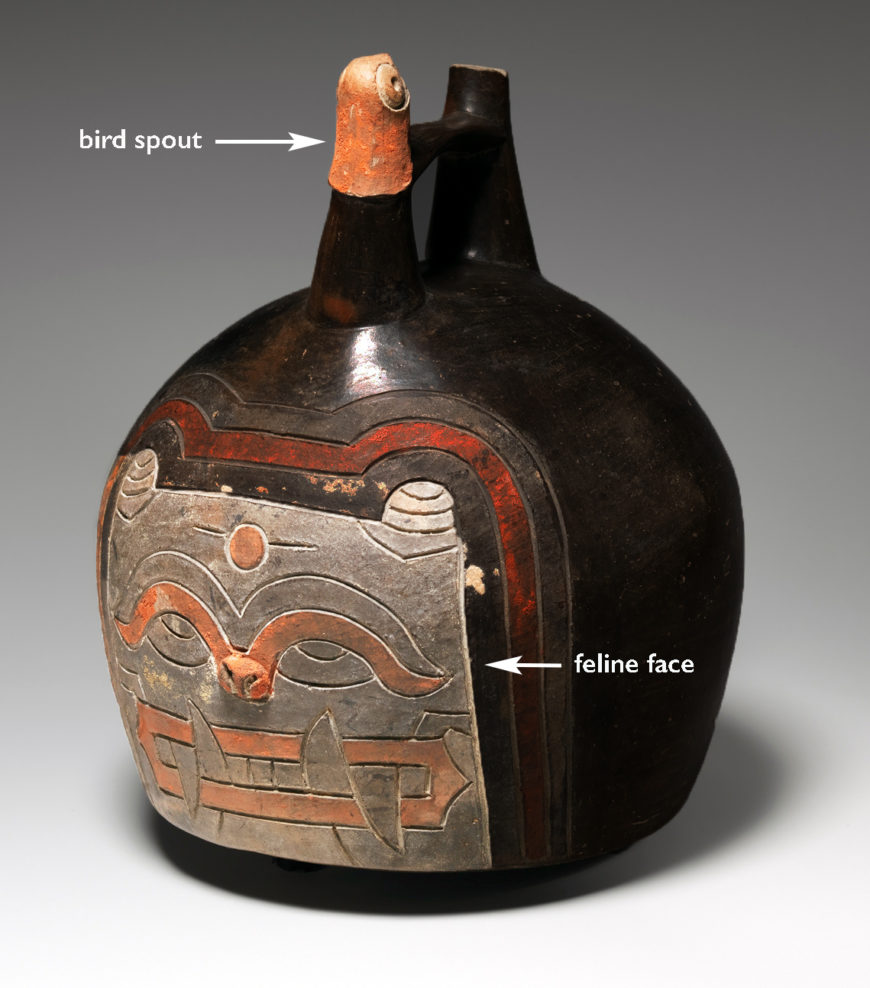

Feline-Head Bottle

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Feline-Head Bottle, 15th-5th century B.C.E., Cupisnique, Jequetepeque Valley (possibly Tembladera), Peru, ceramic and post-fired paint, 32.4 x 20.5 x 13.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Speakers: Dr. Sarahh Scher and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Chavín culture

Chavín de Huántar

Chavín de Huántar is an archaeological and cultural site in the Andean highlands of Peru. Once thought to be the birthplace of an ancient “mother culture,” the modern understanding is more nuanced. The cultural expressions found at Chavín most likely did not originate in that place, but can be seen as coming into their full force there. The visual legacy of Chavín would persist long after the site’s decline in approximately 200 B.C.E., with motifs and stylistic elements traveling to the southern highlands and to the coast. The location of Chavín seems to have helped make it a special place—the temple built there became an important pilgrimage site that drew people and their offerings from far and wide.

At 10,330 feet (3150 meters) in elevation, it sits between the eastern (Cordillera Negra—snowless) and western (Cordillera Blanca—snowy) ranges of the Andes, near two of the few mountain passes that allow passage between the desert coast to the west and the Amazon jungle to the east. It is also located near the confluence of the Huachesca and Mosna Rivers, a natural phenomenon of two joining into one that may have been seen as a spiritually powerful phenomenon.

Over the course of 700 years, the site drew many worshipers to its temple who helped in spreading the artistic style of Chavín throughout highland and coastal Peru by transporting ceramics, textiles, and other portable objects back to their homes.

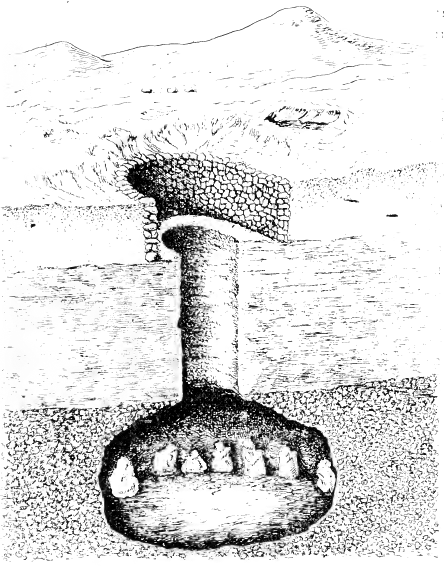

The temple complex that stands today is comprised of two building phases: the U-shaped Old Temple, built around 900 B.C.E., and the New Temple (built approximately 500 B.C.E.), which expanded the Old Temple and added a rectangular sunken court. The majority of the structures used roughly-shaped stones in many sizes to compose walls and floors. Finer smoothed stone was used for carved elements. From its first construction, the interior of the temple was riddled with a multitude of tunnels, called galleries. While some of the maze-like galleries are connected with each other, some are separate. The galleries all existed in darkness—there are no windows in them, although there are many smaller tunnels that allow for air to pass throughout the structure. Archaeologists are still studying the meaning and use of these galleries and vents, but exciting new explorations are examining the acoustics of these structures, and how they may have projected sounds from inside the temple to pilgrims in the plazas outside. It is possible that the whole building spoke with the voice of its god.

The god for whom the temple was constructed was represented in the Lanzón (left), a notched wedge-shaped stone over 15 feet tall, carved with the image of a supernatural being, and located deep within the Old Temple, intersecting several galleries.

Lanzón means “great spear” in Spanish, in reference to the stone’s shape, but a better comparison would be the shape of the digging stick used in traditional highland agriculture. That shape would seem to indicate that the deity’s power was ensuring successful planting and harvest.

The Lanzón depicts a standing figure with large round eyes looking upward. Its mouth is also large, with bared teeth and protruding fangs. The figure’s left hand rests pointing down, while the right is raised upward, encompassing the heavens and the earth. Both hands have long, talon-like fingernails. A carved channel runs from the top of the Lanzón to the figure’s forehead, perhaps to receive liquid offerings poured from one of the intersecting galleries.

Two key elements characterize the Lanzón deity: it is a mixture of human and animal features, and the representation favors a complex and visually confusing style. The fangs and talons most likely indicate associations with the jaguar and the caiman—apex predators from the jungle lowlands that are seen elsewhere in Chavín art and in Andean iconography. The eyebrows and hair of the figure have been rendered as snakes, making them read as both bodily features and animals.

Further visual complexities emerge in the animal heads that decorate the bottom of the figure’s tunic, where two heads share a single fanged mouth. This technique, where two images share parts or outlines, is called contour rivalry, and in Chavín art it creates a visually complex style that is deliberately confusing, creating a barrier between believers who can see its true form and those outside the cult who cannot. While the Lanzón itself was hidden deep in the temple and probably only seen by priests, the same iconography and contour rivalry was used in Chavín art on the outside of the temple and in portable wares that have been found throughout Peru

The serpent motif seen in the Lanzón is also visible in a nose ornament in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art (above). This kind of nose ornament, which pinches or passes through the septum, is a common form in the Andes. The two serpent heads flank right and left, with the same upward-looking eyes as the Lanzón. The swirling forms beneath them also evoke the sculpture’s eye shape. An ornament like this would have been worn by an elite person to show not only their wealth and power but their allegiance to the Chavín religion. Metallurgy in the Americas first developed in South America before traveling north, and objects such as this that combine wealth and religion are among the earliest known examples. This particular piece was formed by hammering and cutting the gold, but Andean artists would develop other forming techniques over time.

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Additional resources:

Chavín de Huántar Archaeological Acoustics Project

Chavin (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

Nose Ornament at the Cleveland Museum of Art

Richard L. Burger, Chavín and the Origins of Andean Civilization, London: Thames and Hudson, 1992.

RL Burger, “The Sacred Center of Chavín de Huántar” in The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes , ed. by RF Townsend (The Art Institute of Chicago, 1992), pp. 265-77.

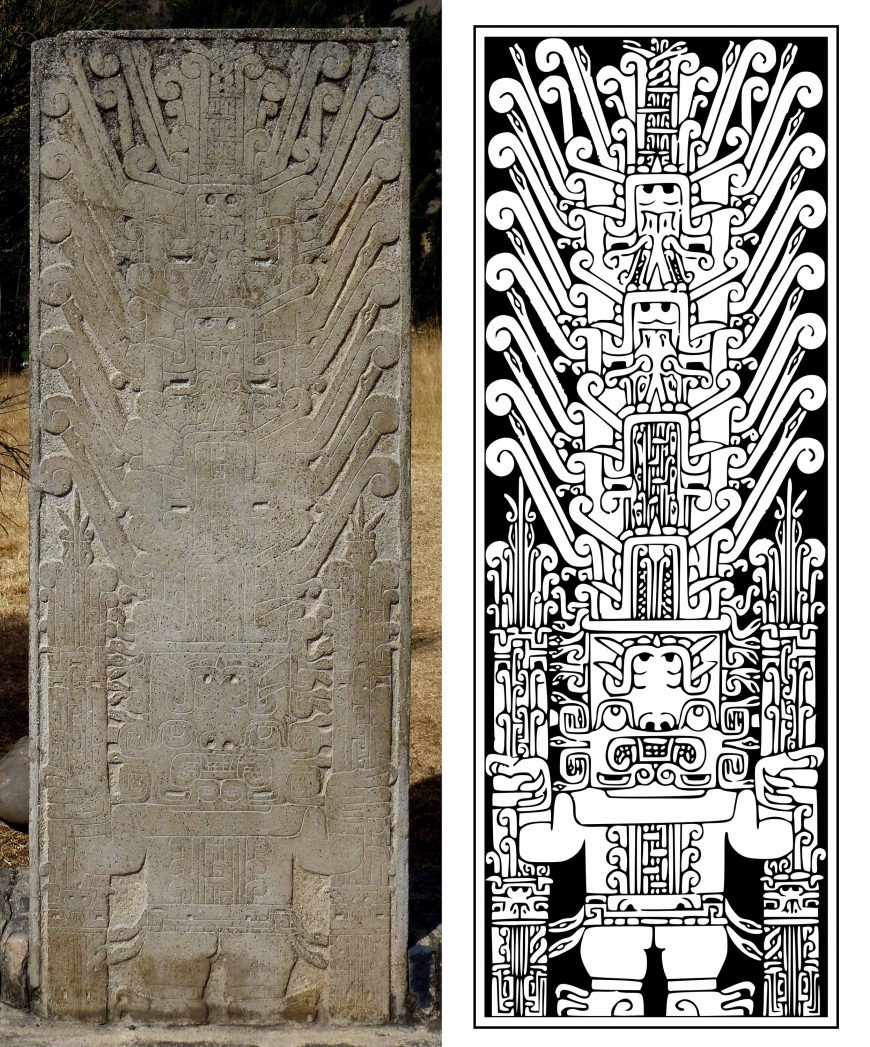

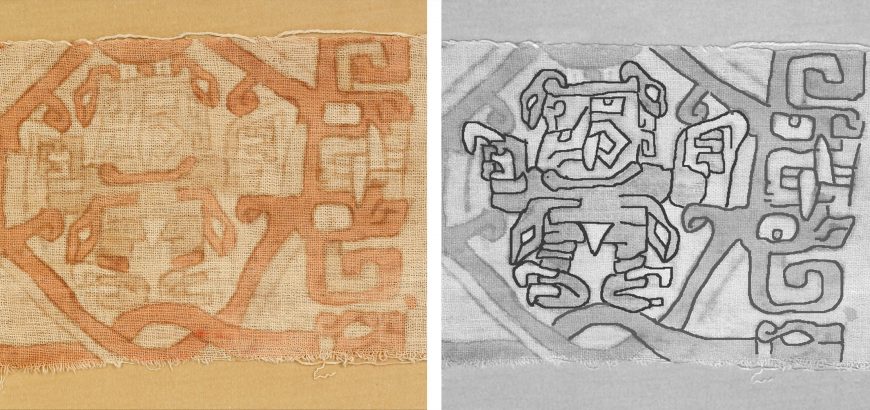

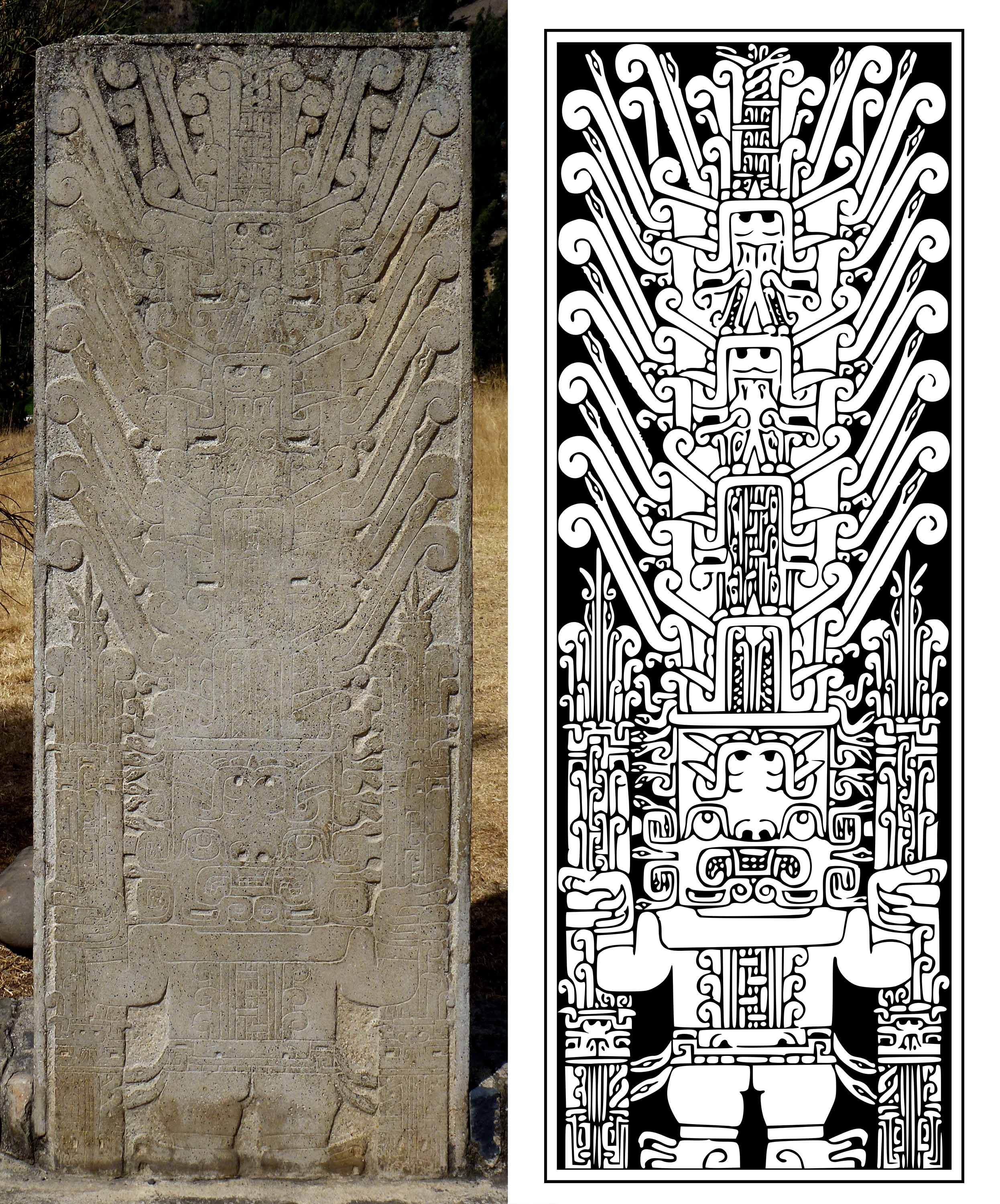

Complexity and vision: the Staff God at Chavín de Huántar and beyond

Art for the initiated

The artistic style seen in stone sculpture and architectural decoration at the temple site of Chavín de Huántar, in the Andean highlands of Peru, is deliberately complex, confusing, and esoteric. It is a way of depicting not only the spiritual beliefs of the religious cult at Chavín, but of keeping outsiders “out” while letting believers “in.” Only those with a spiritual understanding would be able to decipher the artwork.

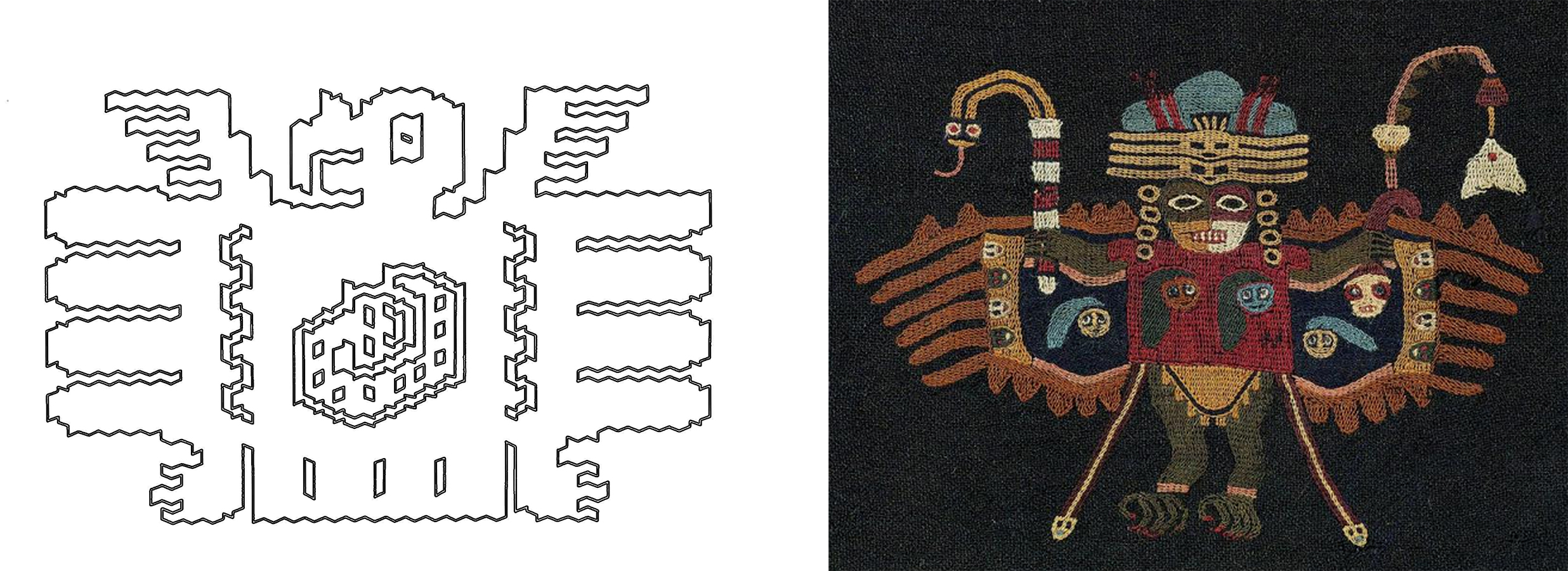

The Raimondi Stele from Chavín de Huántar is an important object because it is so highly detailed and shows Chavín style at its most complex. It is easiest to see in a drawing, because the original sculpture is executed by cutting shallow but steep lines into the highly-polished stone surface, making it very difficult to make out the incised image. This style is deliberately challenging to understand, thereby communicating the mystery of the Staff God, and creating a difference between those initiated in the religion who can understand the imagery, and outsiders who cannot.

Powerful animals

The stele (see video directly below) shows the god holding staffs composed of numerous curling forms. Beneath the god’s hands we see upside-down and sideways faces, and the staffs terminate at the top in two snake heads with protruding tongues. The god’s belt is a compressed, abstracted face with two snakes extending from where the ears should be, perhaps substituting the snakes for hair, and turning the face with its snake-hair into a belt. The god’s hands and feet have talons rather than human fingernails, evoking felines and birds of prey.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\)

These are references to animals that would have been exotic rumors to the people of highland Chavín: the jaguar, the harpy eagle, and the anaconda are all animals that dwell in the lush tropical jungle over the Andes mountains to the east. They are all apex predators, possessing physical qualities like strength, flight, and stealth that become metaphors for the power of the Staff God. Other supernatural imagery from Chavín includes images of caimans, crocodile-like animals that also inhabit the eastern jungles. Most people would never have seen these creatures, rendering them mythical in their own right, and suitable for depicting the mysterious nature of the god.

Multiple faces

The god’s face is actually composed of multiple faces (see video directly below). The eyes in the center looking upward are above a downturned mouth sporting feline fangs, but beneath that we can see another upside-down pair of eyes and a nose that use the same mouth. This is an artistic technique known as contour rivalry, where parts of an image can be visually interpreted in multiple ways. A similar thing is taking place on the god’s “forehead,” where we see another upside-down mouth with four large fangs protruding from it, which when associated with the eyes in the middle completes a full face. Above this multi-faced head is what appears to be an enormous headdress, which is composed of more faces that also multiply using contour rivalry, and have extensions emanating from them that terminate in curls and snake heads.

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\)

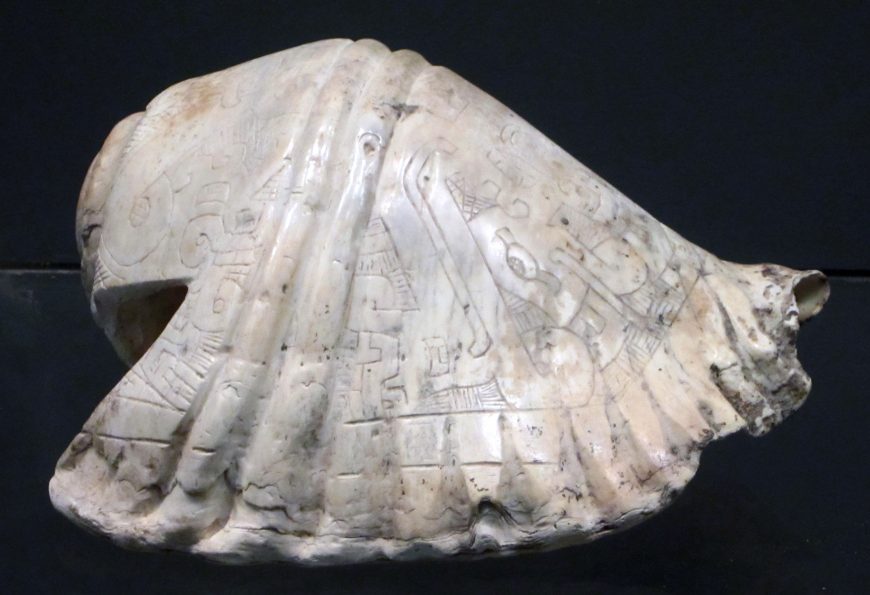

An intricate style

This intricate and confusing style was not just used for large monuments at Chavín. Smaller carved, decorative elements of the site’s architecture also display these kinds of supernatural figures. The two stone slabs seen below are examples of the kinds of sculptures found in cornices and other architectural elements at Chavín.

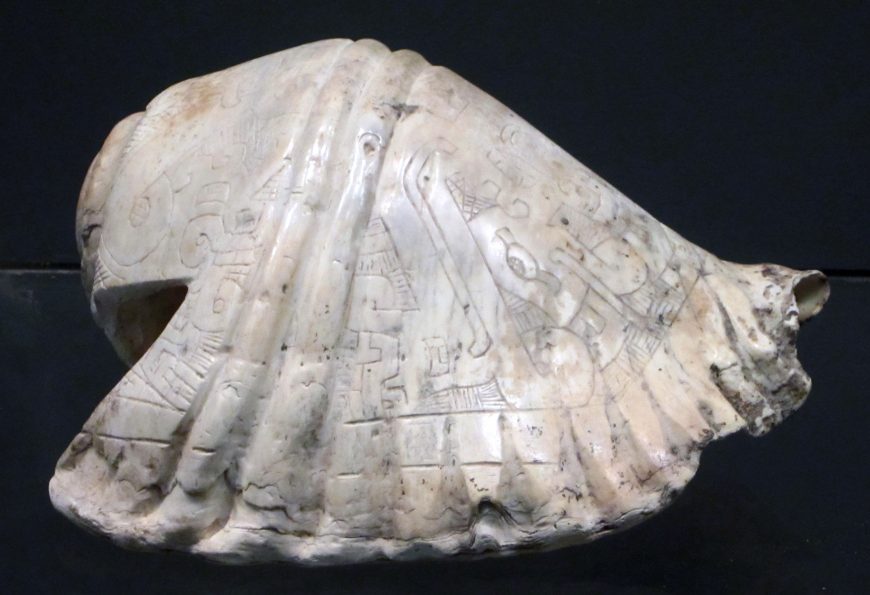

One of these depicts a standing figure with snakes for hair. It sports the same protruding fangs we see in the upside-down heads above the Staff God’s face. Large pendant earrings rest on its shoulders, and in its hands it holds two shells: a Strombus in its right hand and a Spondylus in its left. Spondylus shells are not native to Peru; they thrive in the warm coastal waters of what is now Ecuador, hundreds of kilometers from Chavín. Early on in the history of the Andes, there was a brisk trade in these shells as luxury items.

Strombus can be found in Peruvian waters, but that is the southernmost reach of their range—they are more common in the north. A great number of carved Strombus shells turned into trumpets (called pututu) have been found at Chavín. Far from the ocean, these shells symbolized water and fertility. Furthermore, the Strombus is frequently associated with masculinity, while the Spondylus has feminine associations. The two together therefore signaled generative fertility and the power of the cult to foster agricultural prosperity.

A second carved figure is more enigmatic, and is full of contour rivalry. The main figure appears to be composed of the head to the right, attached to a body with round spots, probably alluding to a jaguar. However, behind the head is another eye, nose, and fanged mouth, and the jaguar spots are joined by an eye with a profile mouth with fangs. Thus, what appears to be one creature at first glance may be as many as three. At the bottom left, we can see another fanged mouth, this one upside-down, but because the stone is broken, we’ve lost its context.

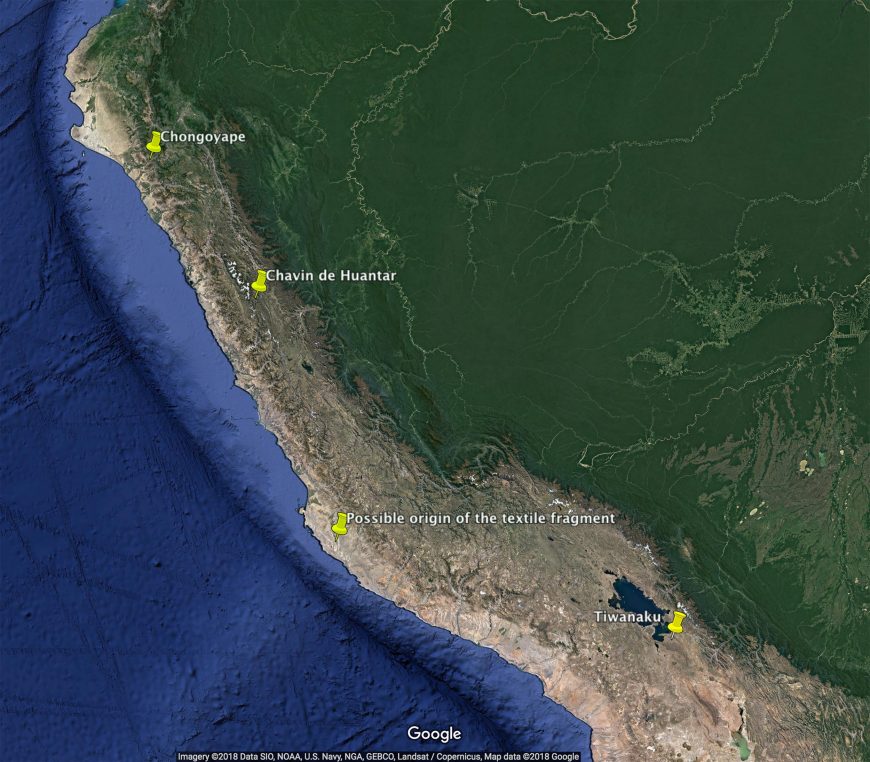

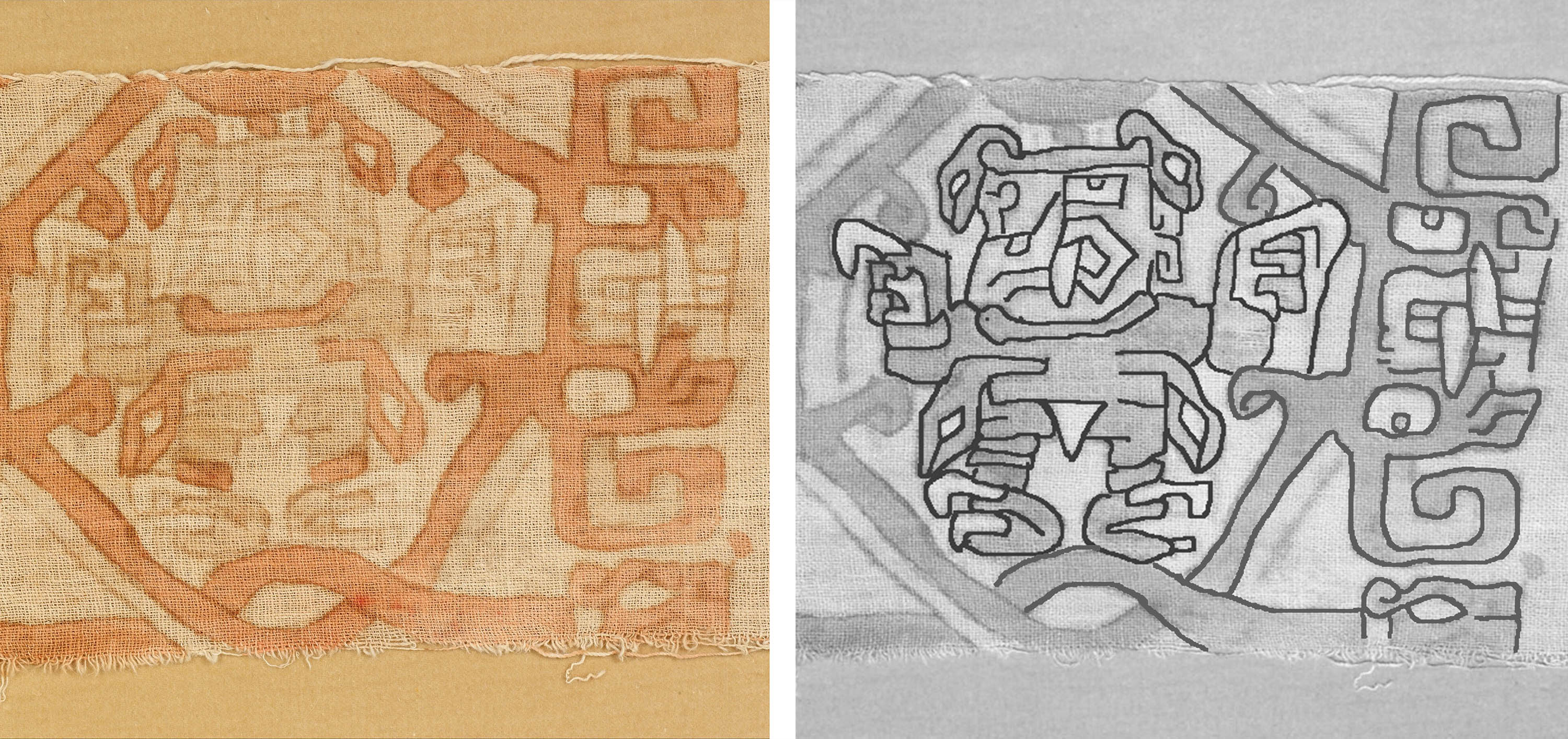

The spread of the Staff God

The image of the Staff God would spread throughout Peru. The imagery’s geographic reach gives us some insight into the contact between distant areas and the diffusion of imagery. Once thought to show the expansion of the cult of Chavín, today scholars are more hesitant to draw direct relationships between Chavín influence and these far-flung images. The Staff God may have had its roots in earlier cultural styles, including the one known as Cupisnique, making Chavín just one of many expressions of this deity. The Staff God’s imagery traveled extensively, far beyond the areas already mentioned.

A Cupisnique gold crown from Chongoyape, Peru, also demonstrates the Staff God’s reach. The crown depicts a version of the god that is simpler than that seen in the Raimondi Stele, but it still uses contour rivalry and the trademark fanged mouths.

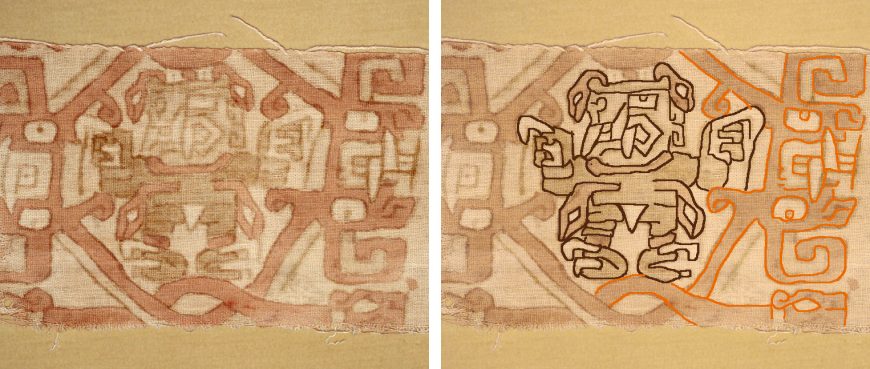

A painted textile fragment with the Staff God is thought to be from the southern Peruvian coast, hundreds of kilometers from Chavín (which is in the highlands). It is woven from cotton, which is a coastal agricultural product, and distinct from the camelid wool that came from the highlands. The Staff God here is shown with the head in profile, and with snakes emerging from the top of the head, with a feline-fanged mouth, snake belt, and taloned hands and feet. The figure is enclosed in a knot-like shape, composed of supernatural figures that blend snake and feline attributes. Other southern coastal textiles with Staff God imagery have been found, including some that render the Staff God as explicitly female, showing how this religious imagery transformed as it traveled.

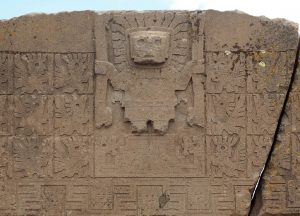

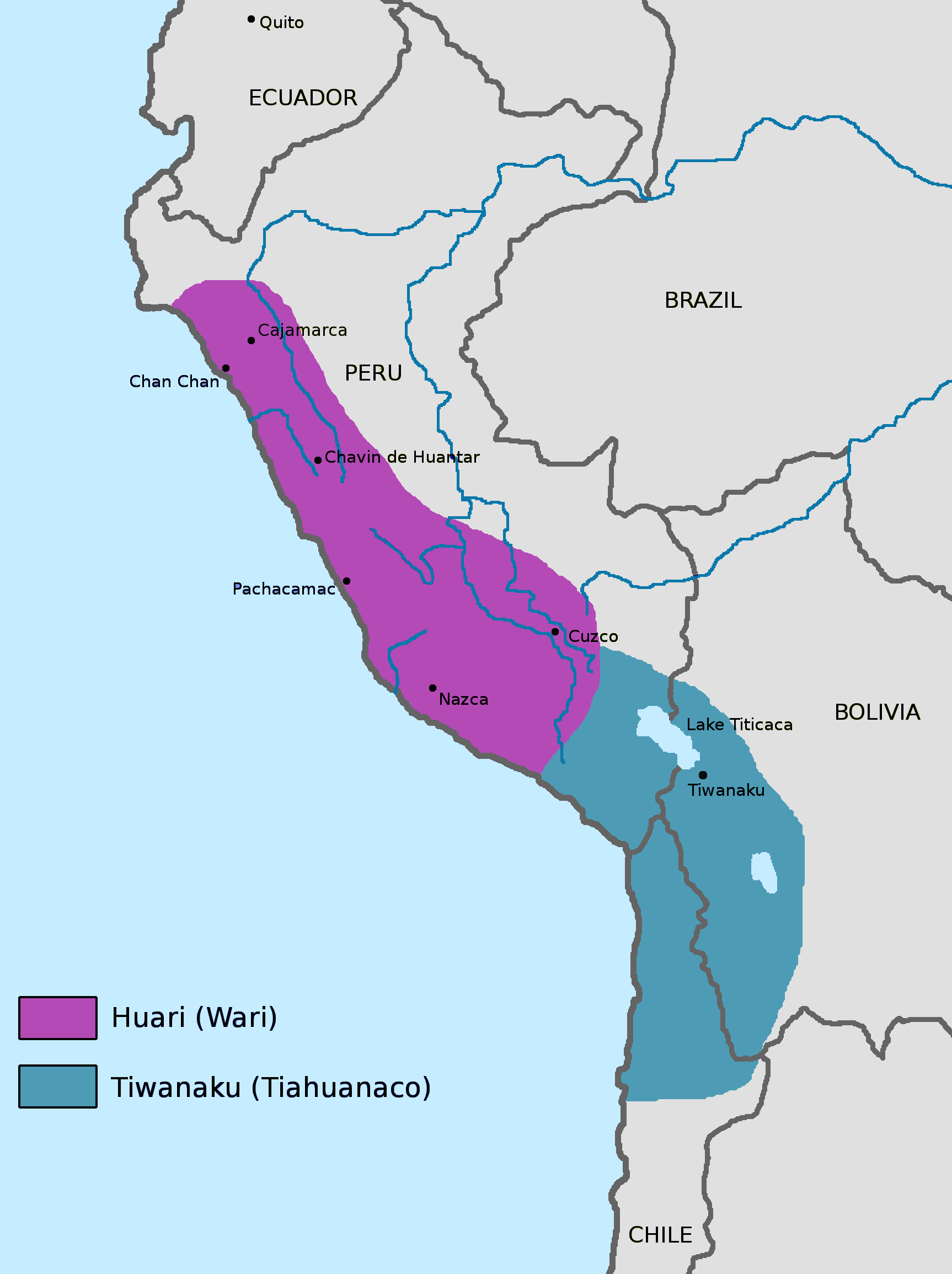

Traveling in time

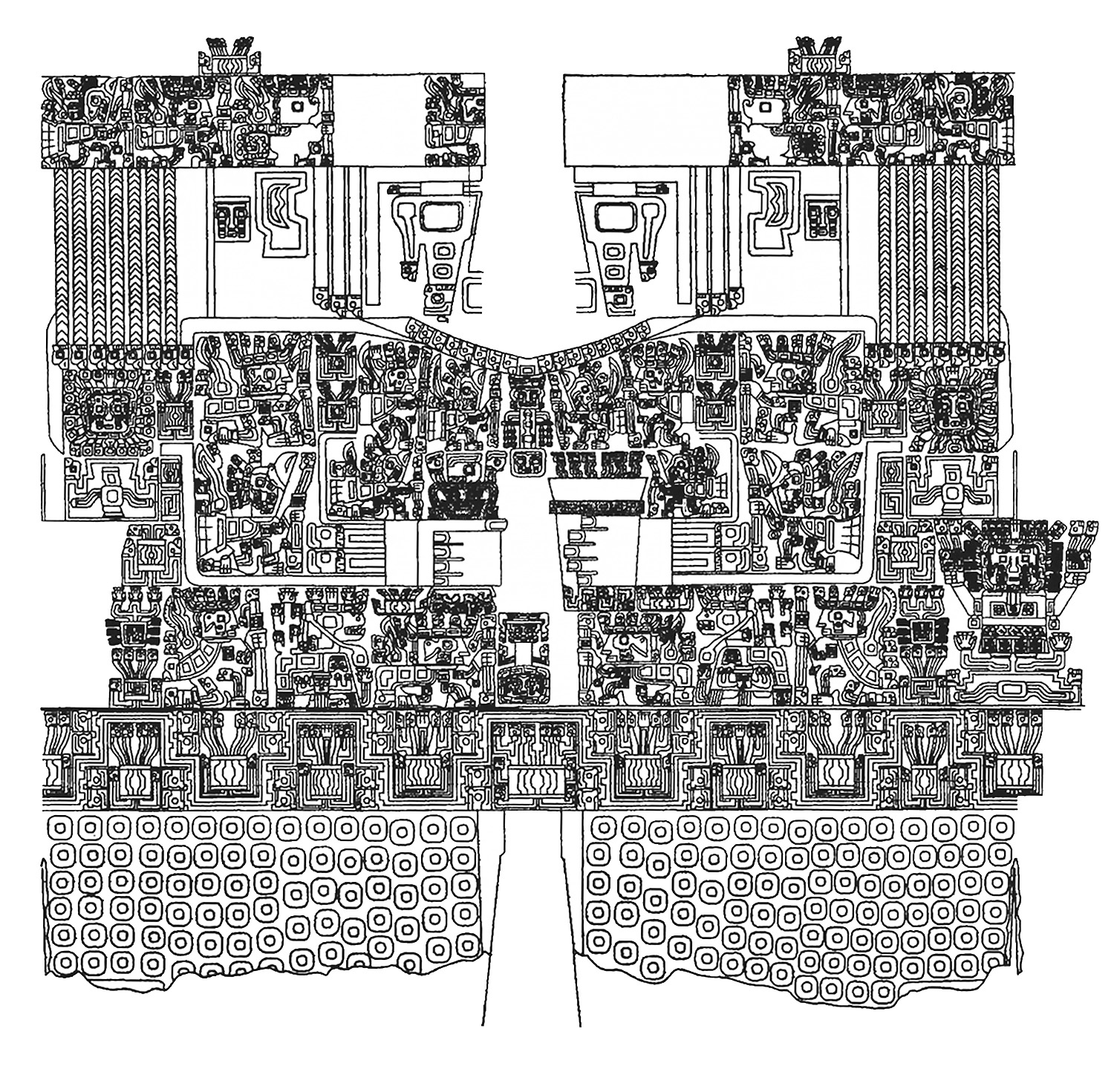

The image of a divine figure holding staffs or similar objects in its hands would persist in Andean art long past the time of Chavín. The so-called “Sun Gate” at the site of Tiwanaku, near lake Titicaca in modern-day Bolivia, is 748 miles (about 1200 km) from Chavín. It dates from around 800–1000 C.E., and so is separated by at least a thousand years from the Raimondi Stele. However, like the Stele, it features an abstracted and intricate style that separates believers from outsiders.

Tiwanaku style is more angular than Chavín, and the Sun Gate has a strong gridded organization that adds to the geometric feel. The central figure of the Sun Gate, while sharing the frontality of the Staff God and the familiar pose (arms at the sides, elbows bent, and vertical objects in its grasp), is also different from earlier iterations. The head is disproportionately large, rendered in a higher relief than the rest of the figure, and features projecting shapes that may represent the rays of the sun. Some terminate in feline heads in profile, a change from the earlier serpents seen at Chavín, Chongoyape, and in the textile fragment. In its hands it holds projectiles and a spear-thrower—weapons rather than elaborate staffs.

The Sun Gate figure stands atop a stepped pyramid shape with serpentine figures emerging from it, a representation of the Akapana pyramid, which mirrored the nearby sacred mountain Illimani not only in shape but by having a series of internal and external channels that allowed rain water to cascade down the side of the structure like the above-and below-ground rivers of the mountain. Not only does it stand in the same pose as the Staff God; it, too, is associated with natural forces, like the mountain, the sun, and the waters of Illimani. The feline heads terminating the rays from the figure’s head are joined by the bird-human hybrid “attendant” figures in the rows to either side.

The meaning of the Staff God image was likely different in each of the places it has been found, an image of the sacred that came from afar and was adopted and adapted to the needs of the local people. In each case, however, we find that the intricate and often inscrutable imagery was a way of keeping believers separate from outsiders.

Additional resources:

Richard L. Burger, Chavin and the origins of Andean civilization (London: Thames and Hudson, 1995).

Julia T. Burtenshaw-Zumstein, Cupisnique, Tembladera, Chongoyape, Chavín? A Typology of Ceramic Styles from Formative Period Northern Peru, 1800-200 BC, doctoral dissertation, University of East Anglia, 2014.

Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, Golden Kingdoms: Luxury arts in the ancient Americas (Los Angeles: Getty Trust Publications, 2017).

Nasca

Nasca Art: Sacred Linearity and Bold Designs

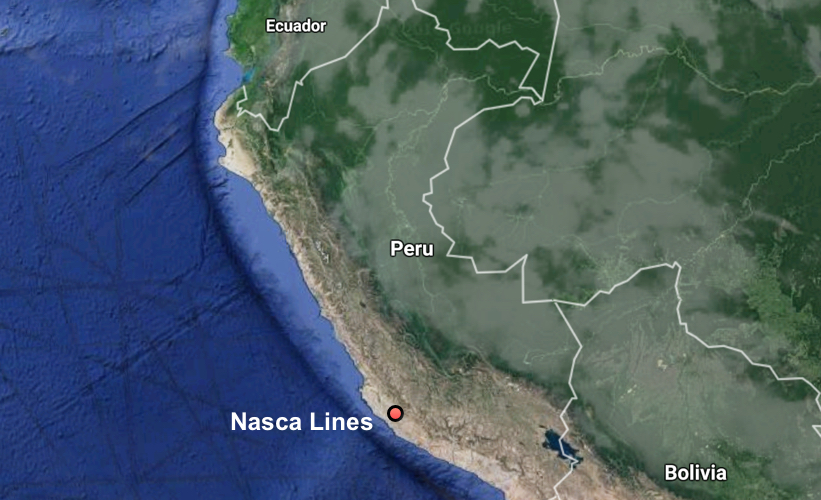

The Nasca (also spelled Nazca) civilization flourished from 100–800 C.E. in the Nasca Desert of Peru’s south coast, located about 200 miles south of Paracas. The Nasca lived in dispersed settlements along the Nasca River, and the site of Cahuachi served as their main ritual and pilgrimage center. The flat desert terrain proved to be a favorable canvas for Nasca artists, which they utilized to create artworks of unprecedented grandeur, size, and sophistication.

The Nasca Lines

The Nasca Lines are geoglyphs consisting of lines and representational images etched onto the desert floor. The lines cannot be viewed in their entirety from the ground, and are best seen either from the surrounding foothills or by plane. The Nasca Lines have garnered the attention of archaeologists, art historians, explorers, journalists, and artists, inspiring a slew of interpretations over the course of nearly a century.

While scholars remain divided on the precise meaning of the lines, all can agree that they were not made by aliens, as the popular show Ancient Aliens would like people to believe. One of the most convincing interpretations put forth by archaeologist Anthony Aveni and his colleagues argues that the Nasca lines traced important underground water sources. The vast majority of the Nasca lines are just that—straight lines, which run parallel, converge, and intersect with one another. In an excessively dry desert climate that receives less than one inch of rainfall per year, access to fresh water would have been a central concern for ancient Nasca peoples.

The Nasca landscape also contains a series of representational images of a monkey, whale, condor, spider, dog, heron, and others. One of the most iconic images is that of the Nasca Line Hummingbird, which features a stylized rendition of this miniscule bird, measuring over 300 feet long. The hummingbird is rendered in bird’s-eye view with outstretched wings, tail, and long characteristic beak that extends to another set of lines.

While the lines seem impossible to create without the use of modern technology, archaeologists discovered that the lines are indeed reproducible with a large labor force and a system of measurement that employs a set of strings or ropes of different lengths. One striking feature of all the figural Nasca lines is they are contour drawings—the lines never cross each other. If one traversed the lines of the hummingbird, for instance, he or she would return full circle to the starting point. This suggests that the animal figures could have each served as special pilgrimage routes. Indeed, the existence of pottery fragments and food remains along the lines indicate frequent human visitation.

Nasca ceramics

Nasca ceramic art also exhibits a strong interest in bold design. The Figure with Human Heads consists of a person gendered as male, either standing or seated, with his arms at his sides. His nose is modeled in three dimensions, but the rest of his facial features are painted, and his body is rendered as the general form of the vessel. He wears a headcloth over his hair, held in place with a criss-crossed band, and a tunic that features a design consisting of black and white stepped motifs arranged into repeating squares. Beneath this pattern is a border decorated in a repeating rhythm of highly abstracted heads seen in profile. The closed eyes and loose hair indicate that they are ritual heads, associated with fertility in Nasca art. (While sometimes referred to as “trophy heads,” archaeologists have found increasing evidence that heads were curated by the Nasca as part of ancestor veneration, and that they were usually not associated with warfare). The use of the monochromatic scheme in the man’s tunic intensifies the design’s visual impact, and is similar to the pattern seen in a vessel depicting an achira (a root vegetable).

The Nasca were interested in issues of design and abstraction centuries before the rise of abstract art in the twentieth century. Nasca earthworks carved into the ground left an indelible mark on the coastal landscape, revealing a great deal about Nasca beliefs and aesthetic traditions. The Nasca introduced a stunning linearity to the arts of the pre-Columbian Andes, which carried through to other aspects of their artistic repertoire.

Additional resources

Rebecca R. Stone, Art of the Andes: From Chavín to Inca (London: Thames & Hudson 2012)

Super/Natural: Textiles of the Andes at the Art Institute of Chicago

Anthony Aveni, “Solving the Mystery of the Nasca Lines,” 53 no. 3 (May/June 2000)

Helaine Silverman, Cahuachi in the Ancient Nasca World (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1993)

“Archaeologists Identify 143 New Nazca Lines,” Smithsonian Magazine

Nasca Geoglyphs

Located in the desert on the South Coast of Peru, the Nasca Geoglyphs are among the world’s largest drawings. Also referred to as the Nasca Lines, they are more accurately called geoglyphs, which are designs formed on the earth. Geoglyphs are usually constructed from strong natural material, such as stone, and are notably large in scale.

Imagine encountering such a drawing. The hummingbird measures over 300 feet in length, and is one of the most famous Nasca Geoglyphs. Among the other celebrated geoglyphs of mammals, birds and insects are a monkey, killer whale, spider, and condor. Various plants, geometric shapes (spirals, zigzag lines and trapezoids), abstract patterns, and intersecting lines fill the desert plain, known as the Pampa, an area covering approximately 200 square miles near the foothills of the Andes. The zoomorphic geoglyphs are the oldest and most esteemed. Each appears to have been made with a single continuous line.

Today it is believed that the geoglyphs were created by the Nasca people, whose culture flourished in Peru sometime between 1-700 C.E. They inhabited the river valleys of the Rio Grande de Nasca and the Ica Valley in the southern region of Peru, where they were able to farm, despite the desert environment—one of the driest regions in the world. The high Andes Mountains to the east prevent moisture from the Amazon from reaching the coast, so there is very little rainfall; water that does arrive, comes from mountain runoff.

The Nasca people are also famous for their polychrome pottery, which shares some of the same subjects that appear in the Nasca Geoglyphs. Remains of Nasca pottery left as offerings have been found in and near the geoglyphs, cementing the connection between the geoglyphs and the Nasca people. Because the quality of the ceramics produced in Nasca is very high, archaeologists deduce that specialists shaped and painted the pottery vessels. This suggests a society that, at its height, had a degree of wealth and a division of labor. However, the Nasca people had no writing. In cultures without writing, images often assume an increased level of importance. This may help explain why the Nasca came together to create vast images on the desert floor.

How were they made?

Since the Nasca geoglyphs are so large, it seems clear they were constructed by organized groups of people and that no single artist made them. The construction of the geoglyphs are thought to represent organized labor where a small group of individuals directed the design and creation of the lines, a process that may have strengthened the social unity of the community. Despite the impressive scale of the geoglyphs, these remarkable works did not require complex technology. Most geoglyphs were formed by removing weathered stones from the desert floor, stones that had developed a dark patina known as “desert varnish” on their surface. Once removed, the lighter stones below became visible, forming the famous Nasca Lines. The extracted darker stones were placed at the edges of the lines, forming a border that accented the lighter lines within. Straight lines could be created by extending cords, one on each side of the line, between two wooden stakes (some of which have been recovered) that guided workers and allowed for the creation of sight lines.

For larger geometric shapes, such as trapezoids, borders were marked and then all the stones on the interior were removed and placed along edges or heaped in piles at the edges of the geoglyph. Broken pottery has been found mixed with the piles of stones. Spirals and animal shapes were made in a similar manner. Spirals, for example, would be formed by releasing slack in a cord as workers moved around in a circular path, moving further and further from the center where the spiraling line begins. For animal forms, such as monkeys, whales, or hummingbirds, portions of the figures might be made in the same manner as the spiral in the monkey’s tail, or the image might be based on a gridded drawing or textile model that was enlarged on the desert floor where lines were staked out to create the figure.

When were they made?

The oldest of the Nasca Geoglyphs is more than 2000 years of old, but, as a group, the Nasca geoglyphs were created over several centuries, with some later lines or shapes intersecting or overlapping with previously created lines. This is just one of the unusual features of these geoglyphs. Even more curious, the drawings are best observed from the air, which is why they did not become widely known until the 1920s after the development of flight. Although it is possible to observe some of the lines from the adjacent Andean foothills or the modern mirador (viewing platform), the best way to see the lines today remains a flight in a small plane over the Pampa (lowlands). These amazing images are so large that they cannot be truly appreciated from the ground. This, of course, raises the question: for whom were the lines made? And, what was their purpose?

What was their purpose and meaning?

Archaeologists are not certain of the purpose of the lines, or even of the audience for whom the lines were intended since they can only be seen clearly from the air (This is now particularly true of the older animal designs). Were they made to be seen by deities looking down from the heavens or from distant mountain tops? Perhaps the numerous theories that have been proposed will eventually be clarified as our understanding of the cultures of ancient Peru increases.

Celestial alignments?

Shortly after the geoglyphs were first investigated, researchers sought an astronomical interpretation, suggesting that the geoglyphs might be aligned with the heavens, and perhaps represented constellations or marked the solstices or planetary trajectories. While some geoglyphs seem connected to celestial events, such as marking the summer solstice (in December) when mountain waters flow to the coast, it is difficult to find celestial alignments for most of the geoglyphs. As far as we know, Andean peoples did not form pictures by connecting the stars in the night sky as we do; rather they looked at the black spaces between stars and saw shapes that they converted into their own reverse “constellations.” It is important to note that these constellations do not seem to match the Nasca geoglyphs.

Deities or ceremonial walkways?

Many other reasonable theories have been proposed. Some scholars have suggested that the geoglyphs represent Nasca deities, or formed a calendar for farming, or represented ceremonial walkways. Because some of the lines do seem to direct people to Cahuachi, a Nasca religious center and pilgrimage destination, it seems possible that ancient Nasca people walked the lines. It is also possible that Nasca people ritually danced on the lines, perhaps in connection with shamanism and the use of hallucinogens. The geoglyphs, particularly the early animals which are clearly spaced apart from each other, may also have strengthened group identity and reinforced social interaction patterns as individual groups of people may each have tended or “owned” one of the geoglyphs,

A discredited theory proposed that the geoglyphs are the result of alien contact. While this is sensationalist and helped to secure the popular fame of the Nasca geoglyphs, there is no evidence to support this assertion. Archaeologists and scientists have rejected this proposal and it is important to recognize the implication of this theory is that the Nasca people needed the influence of aliens peoples to create their geoglyphs. We know that the technology to manufacture the geoglyphs was available to the Nasca people and that they had a social system that was fully capable of organizing and producing large geoglyphs. We also know that the designs are consistent with other art forms native to Nasca culture.

Farming, fertility, and water?

Among the most promising recent theories, archaeologists have begun to secure a link between the geoglyphs and farming, which sustained the Nasca people. Some geoglyphs may deal with fertility for crops; others may be associated with the water needed to raise the crops. In a desert, water is the most important commodity. In Andean mythology the mountains are revered as the home of the gods. It has been suggested that the lines were intended to be visible to the gods in the mountains. Some lines also seem to point in the direction of the mountains — the origin of fresh water for the desert South Coast of Peru. Snow pack melts high in the mountains and becomes runoff and a vital source of water for the coast. In fact, ancient underground water channels are sometimes marked on the surface by Nasca geoglyphs, particularly at the points of intersection. These have been dubbed “ray centers,” spots where lines converge. Offerings have been found at these points, including conch shells. The spirals on the desert floor, in the monkey’s tail, and as independent abstract designs, may refer to the spirals found in conch shells and thus may reference water. This same shape appears in Nasca puquios —gradually descending tunnels that tap ancient subterranean aquifers and water channels. Puquios have been described as wells, and formed part of this ancient irrigation system. Puquios, found in Nasca (and elsewhere in Peru), allowed people to reach water in times of drought. Geoglyphs other than spirals may also be directly associated with water.

Preservation

Because the Nasca Geoglyphs were made directly on the earth by rearranging stones on the desert floor, these giant images are actually quite vulnerable to damage. In time the lighter-colored stones exposed by the Nasca people may attain their own patina, making them less visible, but the designs face greater threats from vehicle and pedestrian traffic. Crossing the lines can damage their borders and make the images less distinct. Because of this, the Peruvian government has created a mirador (viewing platform) along the Pan American Highway where visitors can climb to view a few drawings without damaging the lines.

In the end, it is likely that the Nasca Geoglyphs served more than one purpose, and these purposes may have changed over the centuries, especially given that new lines often “erased” older ones by “drawing” over them. It does appear that many geoglyphs made reference to water and agricultural fertility, and were used to promote the welfare of the Nasca people. The geoglyphs were also a place where people gathered, perhaps for pilgrimage, perhaps to walk or dance on the lines in a ritual pattern. As a gathering place, the Nasca geoglyphs may additionally have turned the Pampa into a map of social divisions, where different families or clans tended different geoglyphs. Although we do not know exact details, we can surmise that the geoglyphs represent a community investment meant to serve this ancient people.

Backstory

In January, 2018, a semi truck traveling through Peru on the Pan-American highway veered off the road and plowed through the desert. The deep ruts that it made damaged several of the Nasca lines. Though the area is clearly marked as a protected zone, according to the archeologist Johnny Isla , co-director of the Nasca-Palpa Project, cases like this “occur daily.” The driver, who authorities suspect may have been trying to avoid a toll, was charged with an “attack against cultural heritage.”

Human interventions like this constitute the main threat to the Nasca-Palpa area, whose geoglyphs extend across almost 300 square miles. In 2014, Greenpeace activists damaged the desert floor around the famous hummingbird geoglyph as they lay out a large protest sign meant to be seen from the air. Their action was a protest against climate change during the United Nations summit in Lima, and was not intended to damage the site; the organization has since apologized. However, the marks made by the activists’ footprints have been deemed possibly “irreparable” by Luis Jaime Castillo Butters, a professor of archeology and Peru’s Vice Minister for Cultural Heritage. “A bad step, a heavy step … marks the ground forever,” he said . “There is no known technique to restore it the way it was.”

The construction of the Pan-American highway has also increased the risks to the area, not only because of vehicles that can potentially veer off the road, but also because rains and mud can wash off of the surface and damage the lines .

Nasca-Palpa was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. In contrast to many other at-risk heritage sites around the world, UNESCO states that

Even though there have been some impacts caused by natural and human factors, these have been minimal and the geoglyphs maintain their authenticity and express their high symbolic and historic value even today.

The most pressing need, now being discussed by Isla and others , is for better, 24-hour monitoring of the area — possibly using drone technology — so that human incursions on the site can be quickly addressed and avoided.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources:

Birds of the Andes on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

UNESCO World Heritage webpage for Nasca-Palpa

Anthony Aveni, Between the Lines (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000).

Jeffrey Quilter, The Ancient Central Andes (London and New York: Routledge, 2014).

Johan Reinhard, The Nazca Lines: A New Perspective on their Origin and Meaning (Lima: Editorial Los Pinos, Sixth edition 1996).

Helaine Silverman and Donald A. Proulx, The Nasca (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2002).

“Rains damage Peru’s Nazca lines,” The Telegraph, January 20, 2009

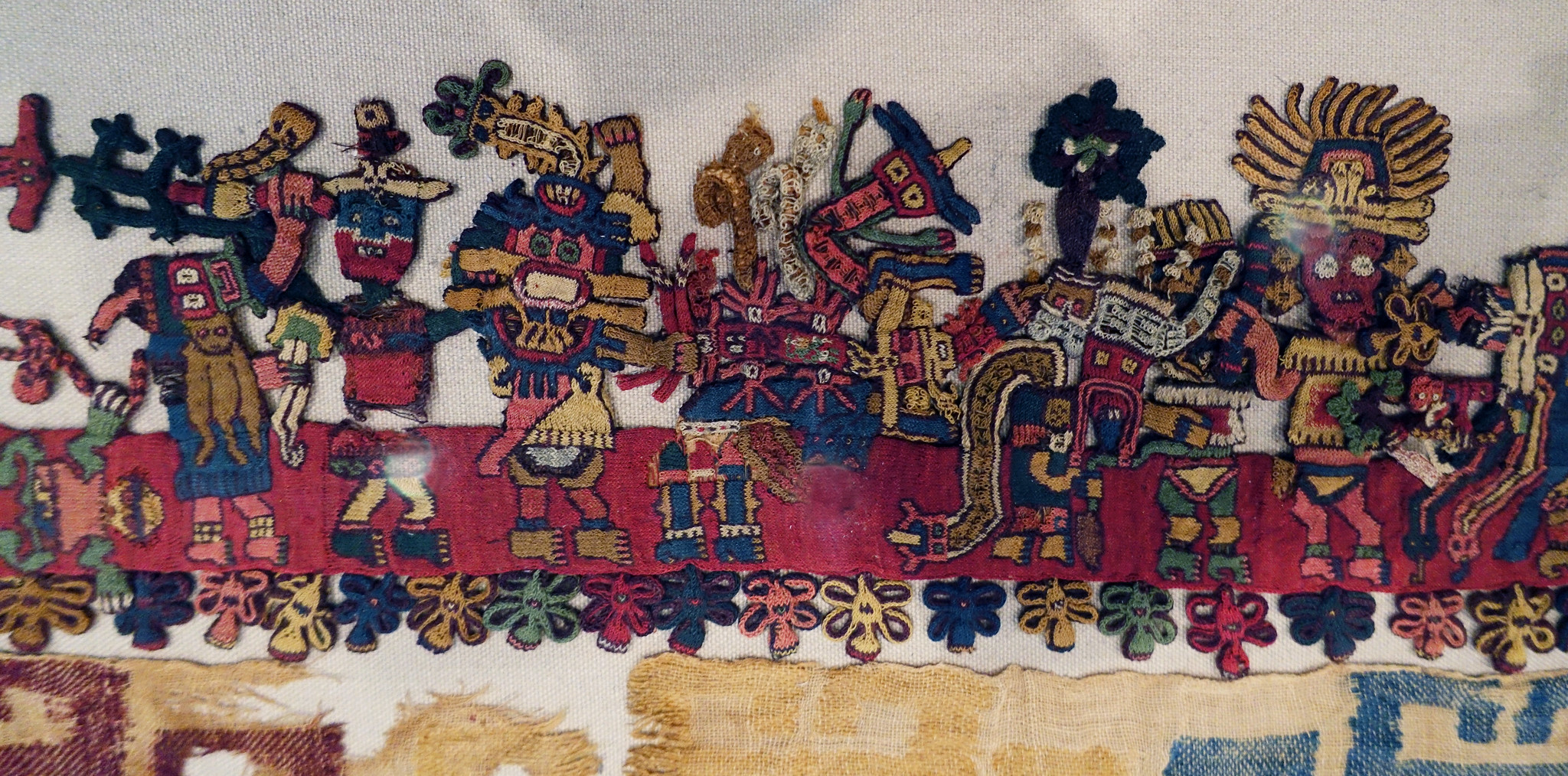

The Paracas Textile

Mummy bundles

One of the most extraordinary masterpieces of the pre-Columbian Americas is a nearly 2,000-year-old cloth from the South Coast of Peru, which has been in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art since 1938.

Despite the textile’s small size (it measures about two by five feet), it contains a vast amount of information about the people who lived in ancient Peru; and despite its great age and delicacy, its colors are brilliant, and tiny details amazingly intact. This is due to the arid environment of southern Peru along the Pacific shore, where it is so dry that organic material buried in the sand remains well preserved for hundreds or even thousands of years.

In the ancient cemeteries on the Paracas Peninsula, the dead were wrapped in layers of cloth and clothing into “mummy bundles.” The largest and richest mummy bundles contained hundreds of brightly embroidered textiles, feathered costumes, and fine jewelry, interspersed with food offerings, such as beans. Early reports claimed that this cloth came from the Paracas peninsula, so it was called “THE Paracas textile,” to mark its excellence and uniqueness. Currently, scholars have revised this provenance, and now attribute the cloth to the related, but slightly later Nasca culture.

Thread by thread

Recently, the Brooklyn Museum has posted high quality, close-up views of this masterpiece online, allowing viewers to scrutinize the textile, thread by thread. Such a detailed inspection has not been possible since the piece was first made. With simple tools, the early cultures of the Andean region of South America produced textiles of astonishing virtuosity. Some extremely fine pieces, like this one, are too delicate to have served any utilitarian purpose, and so are considered ceremonial.

Like some other very fine cloths, the Brooklyn textile is finished so carefully on both sides that it is almost impossible to distinguish which is the correct side. Although the central cloth and its framing dimensional border are created by different techniques, both display perfect reversibility—except for three border figures. These three—instead of being duplicated on the back (as if flipped in mirror image), like all the others—appear in back view on one side of the cloth, thereby designating a “front” and “back” to the textile.

The central cloth’s design of 32 geometric faces is created by “warp-wrapping,” a technique in which colored fleece is wound around sections of cotton warp threads before weaving.

Because the central cloth and the border have different color palettes, they may have been created at different times. The triple-layer border has colorful outer veneers of wool “crossed-looping” that envelop inner cotton cores of looping or weaving.

“Crossed-looping” resembles knitting (but is accomplished with a single needle); in areas where the threads are broken, it is possible to glimpse the underlying cotton substrates. While the cotton is off-white, the wool is dyed in jewel-bright tones.

The combination of materials suggests extensive trading relationships: for while cotton was grown in coastal valleys, wool came from camelids (such as the llama, alpaca, and vicuña) that live at high altitudes in the Andes mountains.

Monstrous hybrids

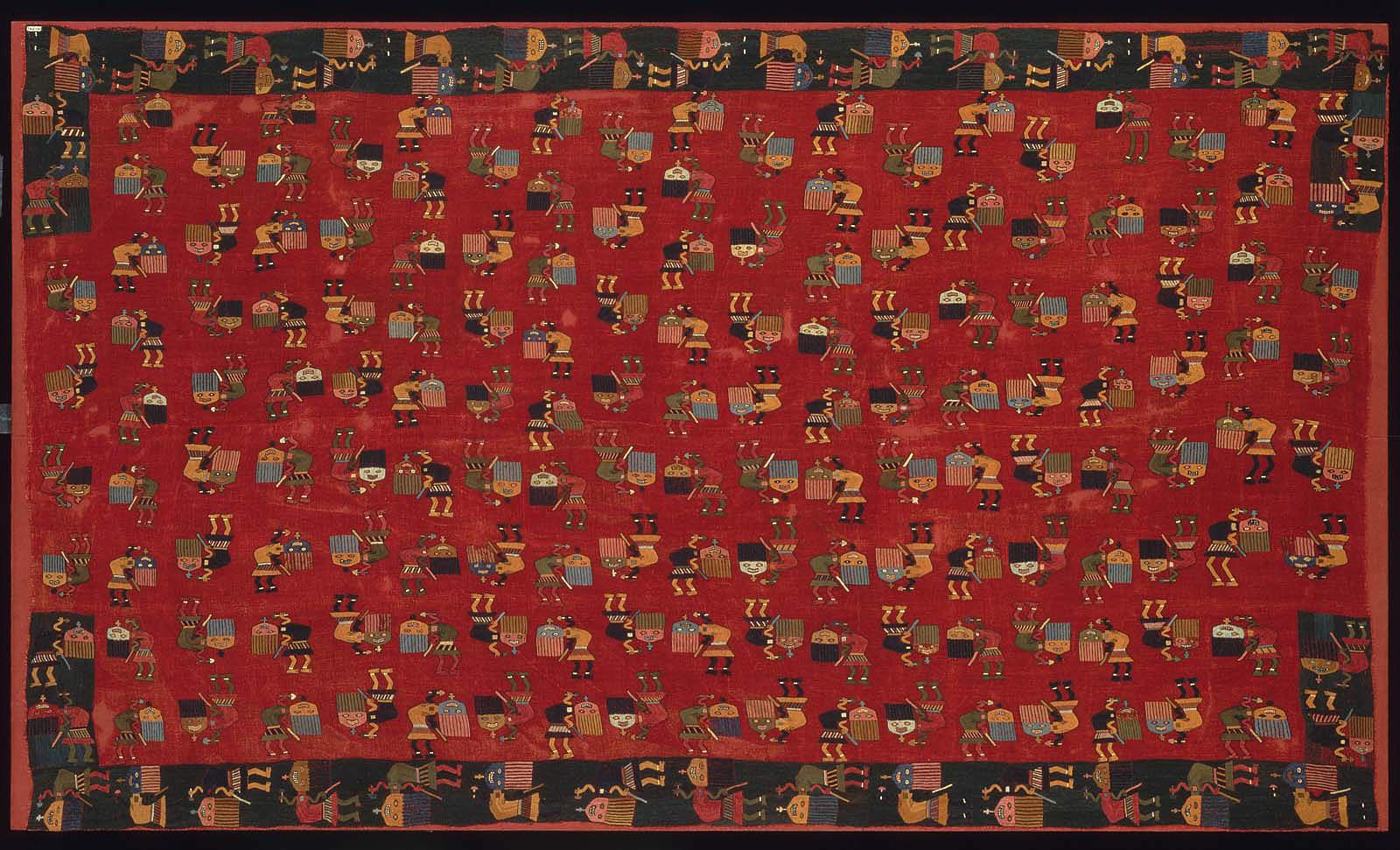

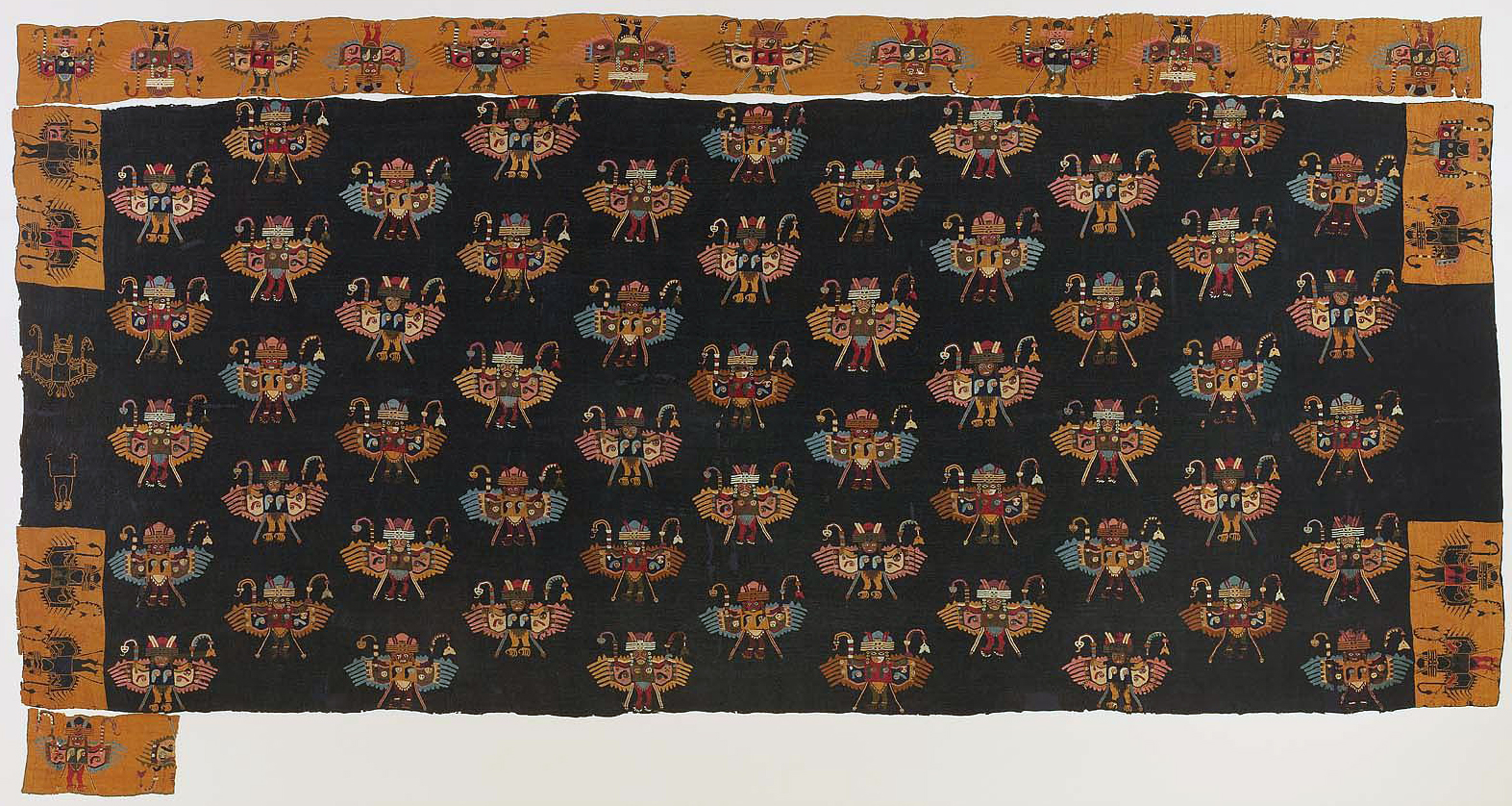

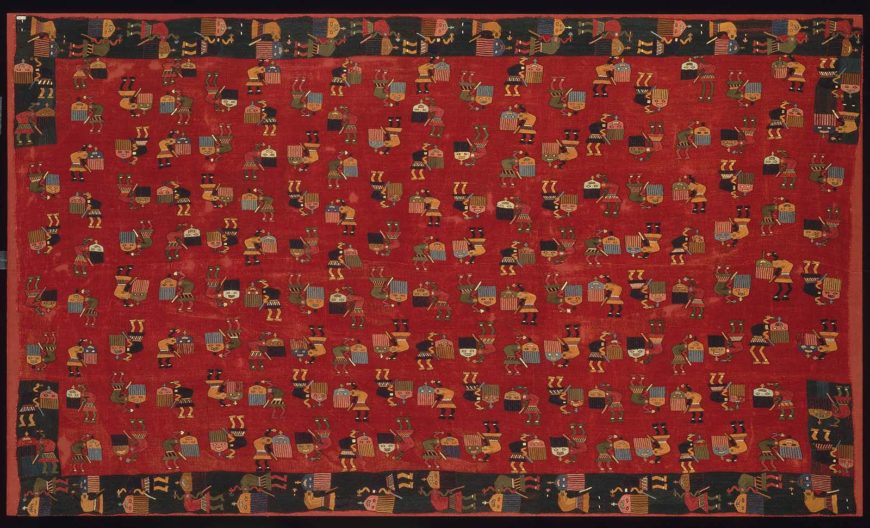

On the border, a parade of 90 figures is linked together on their lower bodies, which are worked two-dimensionally against a red background.

Each figure’s upper body and head is constructed as a separate unit, and attached to the woven strip. The upper bodies are worked in bas-relief, with some parts projecting outwards from the plane of the fabric. Tiny components (like leaves and feathers) were worked as separate pieces and then attached, giving a wonderful three-dimensionality and liveliness to the figures, especially because they mingle and overlap.

The parade is arranged in four, single-file, L-shaped lines that proceed around each corner of the cloth. A wide variety of types appear, including human, animal, and monstrous hybrids. Some figures are unique, others are twins, triplets, or even sextuplets; a few are in related groups.

Most of the animals and plants that appear can be tied to species still found on the South Coast, and many human figures wear or carry items that directly relate to the archaeological record.

Their jewelry, for example, corresponds to specimens formed from thin sheets of gleaming gold. These include: “forehead ornaments” (shaped like a bird with outstretched wings); “hair spangles” (disk or star shapes that dangle from the wingtips of the forehead ornament); slender, feather-shaped headdress “plumes;” and “mouthmasks.” Mouthmasks hung from the nose septum, and had flaring extensions, like cat whiskers.

Garments

The border figures’ clothing also matches examples found archaeologically, and some bear minuscule designs that faithfully represent embroidered decorations found on life-sized garments. Some wear wrap-around dresses of a style worn by women in ancient times; others wear two-part outfits, associated with men (below). The largest and most beautifully decorated garments were mantles that draped over the shoulders, and fell to the knee. By examining stitches on actual mantles, archaeologists have determined that teams of artists worked on them, sitting side-by-side.

Other border details, rather than realistic, seem to be fantastic or mythological. The severed heads (sometimes called “trophy heads”) brandished by some figures, for example, sometimes sprout flourishing plants—as if to suggest themes of sacrifice and fertility. And snake-like streamers that flow from some figures do not correspond to any known object, and may indicate supernatural qualities.

When they depicted clothing, Paracas and Nazca artists often added a face, or an animal body to the loose ends of fabric hanging behind a wearer. This artistic convention seems to suggest the lively movements of cloth fluttering behind a wearer, and hints that these ancient people considered cloth a precious carrier of vitality: an interpretation that seems warranted because this vibrant textile gives us such an evocative and animated glimpse into their world.

Backstory

The Paracas Textile is only one of hundreds of similar textiles that originate from multiple burial sites on the Paracas peninsula. These burials were first identified and excavated by the renowned Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello in the 1920s. For political reasons, Tello was forced to abandon the site in 1930, and, without a team of archaeologists to oversee the area, a period of intense looting followed. It is now believed that a great number of the Paracas textiles in international museum collections were acquired as a result of this looting, which occurred most heavily between 1931 and 1933.

A large group of these illegally acquired textiles is held by the Gothenburg Collection in the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden. The objects were smuggled out of Peru by the Swedish consul in the early 1930s, and donated to the city of Gothenburg. The museum and city fully acknowledge the objects’ illicit provenance, and have been working with the Peruvian government on a plan for their systematic return. As stated on the museum website,

Large quantities of Paracas textiles were illegally exported to museums and private collections all over the world between 1931 and 1933. About a hundred of these were taken to Sweden and donated to the Ethnographic Department of Gothenburg Museum. Today, problems associated with looted artifacts and illicit trade in antiques are better acknowledged and being addressed.

Though Peru began lobbying for repatriation in 2009, Gothenburg has been somewhat slow to respond to the requests, partly due to the fragile condition of the textiles. According to the museum website, even the transport of these objects between the museum’s archives and their exhibition space in Sweden—a distance of only a few kilometers—has resulted in their deterioration. Despite these concerns, a plan has been put in place to systematically return some of the textiles to Peru. The first four were delivered in 2014, and another 79 in 2017. Further works are set to be returned by 2021. The repatriated textiles are now in the possession of Peru’s General Directorate of Museums of the Ministry of Culture.

The case of the Gothenburg Paracas textiles highlights the need not only for governmental and institutional agreements regarding the restitution of illegally acquired objects, but also for oversight concerning the continued stewardship and preservation of these fragile artworks.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources:

This textile at the Brooklyn Museum

The Gothenburg Collection of Paracas textiles

Article on the looting of Paracas textiles on Trafficking Culture

“Peru recovers 79 pre-Hispanic textiles illegally kept in Sweden,” The Local, December 15, 2017

“Peru recovers Paracas textiles,” Diario UNO, December 15, 2017

“Sweden Returns Ancient Andean Textiles to Peru,” The New York Times, June 5, 2014

Frame, Mary. 2003–4. “What the Women Were Wearing: A Deposit of Early Nasca Dresses and Shawls from Cahuachi, Peru.” Textile Museum Journal, 42/43:13–53.

Paul, Anne. 1990. “Paracas ritual attire: symbols of authority in ancient Peru,” Civilization of the American Indian series. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Paul, Anne. 1991. Paracas art & architecture : object and context in South Coastal Peru, 1st ed. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Silverman, Helaine. 2002. “Differentiating Paracas Necropolis and Early Nasca Textiles,” Andean archaeology II: Art, Landscape, and Society, edited by W. H. Isbell and H. Silverman. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 71–105.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Paracas

Paracas, an introduction

Sand and sea

Imagine living in the driest desert on earth located next to the richest ocean on earth. How would these extremes shape social and religious life? What kind of mythology would the drama of this landscape generate? Some ideas can be found in an ancient south-coastal Peruvian people now known as Paracas, from the later Inka Quechua word para-kos, meaning “sand falling like rain.” Paracas refers to both an arid south coastal peninsula and the culture that thrived in the region c. 700 B.C.E. to 200 C.E. The area is a starkly beautiful desert of ochre red, yellow, and gold sediments juxtaposed with the vivid Pacific Ocean. The ocean, enriched by the icy Peruvian current, is a haven for marine life. Ancient inhabitants, likely drawn to the ocean’s resources, had to make do with small coastal rivers trickling down from the Andes for fresh water and agricultural opportunities. In this environment, with visual contrasts so extreme the landscape approaches Color Field abstraction, small villages that depended on fishing and farming created one of the most extraordinary cultures and art traditions in the ancient Americas.

The Pacific bounty and the cotton grown in coastal river valleys gave Paracans the means to support a rich culture and forge reciprocal trade relationships with other Early Horizon highland cultures, principally Chavín. As a result, they assimilated and transformed art and ideas from the highlands, while inventing new beliefs and accompanying art forms that were largely inspired by their unique coastal ecology. Unlike other coastal and highland Andean communities, Paracans did not pursue monumental architecture, rather, they directed their considerable creative energies to textiles, ceramics, and personal regalia.

Belief in an afterlife led to the creation of subterranean burial chambers filled with elaborate mummy bundles and artifacts. Remarkably preserved in the arid coastal desert, the burials were forgotten and undisturbed for nearly 2,000 years. They were discovered in the early 20th century by Peruvian archeologist Julio C. Tello. The contents of these burials constitute the only known records of Paracas culture.

Mummy bundles and personal adornment

Most individuals were modestly wrapped in rough, plain cotton fabric to form a mummy bundle. Some adult males, presumably elites, were wrapped in multiple layers of vividly colored, elaborately woven and embroidered textiles made with cotton from the coast and camelid wool imported from the highlands. Ceramics, gold items, spondylus shells, feather fans, and individual feathers also accompanied these individuals.

Before his death and burial, an elite Paracas man would have been a dazzling sight in the desert, showing off concentrated finery that exuded status, power, and authority. These individuals are generally understood to be the religious and political leaders of Paracas chiefdom society, whose leadership and ritual duties likely continued in the afterlife. Such elites needed all their ritual attire and accessories to perform their duties and roles effectively on both sides of life and death, much like the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Mummies may also have helped to maintain the tenuous desert agricultural cycle (often disturbed by El Niño climate events). As metaphorical seeds germinating the land, some bundles contained cotton sacks of beans rather than human bodies.[1]

Burial artifacts

The Paracas achievements in ceramic and textile arts are among the most outstanding in the ancient Americas. The majority of Paracas ceramics were decorated after firing, with plant and mineral resin dyes applied between incised surface lines to build an image in abstract bands. In a final, transitional stage, pre-fire monochrome clay slips were applied to vessels in the shape of gourds, resulting in smooth, elegant wares.

Other notable items found in the burials included pyro-engraved gourd bowls, as well as gourd rattles and ceramic bugles, revealing the culture’s interest in musical performance. Textiles were, without question, the most outstanding of the burial finds in both quantity and quality, with every known weaving and embroidery technique mastered. Their embroidered imagery is also a form of text and the source of nearly all interpretations of Paracas beliefs and conceptions of their ritual life.

Mythical imagery in textile art

Linear Style

Complex textile imagery was likely accompanied by equally complex oral narratives. At the start of the Paracas textile tradition, c. 700 B.C.E., the imagery is dominated by the traditional Andean animal triad of serpent, bird, and feline, rendered in an abstract style known as the Linear Style and accompanied by their own creation, the Oculate Beings.

Oculate Beings were named for their enormous eyes, possibly inspired by the coastal burrowing owl or the enlarged eyes of a person in trance, and are believed to be key Paracan supernatural figures due to their frequent and enduring presence in Paracas art. Oculate Beings appeared in both humanoid and zoomorphic forms. Art historian Anne Paul identified eight distinct Oculate Beings based on different animals and poses: serpent, bird, and feline, symmetrical, seated, inverted head, flying, and with streaming hair.[2] Paracas embroiderers developed the visual potential of the Linear style to the highest degree, embedding images of animals and Oculate Beings into complex visual effects.

Block Color Style

Beginning around 200 B.C.E., textile embroiderers added the curvilinear Block Color style to their production, resulting in an explosion of new forms and figures. Block Color embroidery broke away from the Linear Style iconographic template to include human figures in ritual costume, human/animal composite figures, and elaborate composites of multiple animals. Sprouting seeds, insects, flowers, serpents, sharks, the pampas cat, and in particular a wide variety of coastal and highland birds dominate this later phase of Paracas embroidery, and there are as many distinct figures as there are individual garments. This final, figural phase also often featured human figures in a state of flight or trance, akin to those found on both earlier and contemporaneous ceramics. While precise meanings remain elusive, the imagery suggests an intense interest in agricultural fertility, as well as an increasingly complex mythology and accompanying ritual activities.

An enduring enigma

Much about Paracas culture will always remain a mystery. Their artistic record reveals a set of beliefs and rituals reflecting their culture’s dependence on the natural world and concern with perpetuating agricultural cycles, the important role of animals in political and religious activities, and a deep investment in the afterlife. The major works of Paracas artists, particularly those expressed in the embroidered figures that embellish woven textiles, are a pinnacle of Andean textile art and acknowledged as among the most accomplished fiber arts ever created. In the trajectory of Andean art, Paracas stands as an independent, inventive coastal counterpart to Chavín. Paracas culture was also a vehicle for transferring both textile and ceramic technology and iconography to the slightly later, south coastal Nasca culture, before disappearing forever into the golden desert sand.

Notes:

- Lisa DeLeonardis and George F. Lau, “Life, Death, and Ancestors,” in Andean Archeology, ed. Helaine Silverman (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), p. 103

- Anne Paul, “Continuity in Paracas Textile Iconography and its Implications for the Meaning of Linear Style Images,” in The Junius B. Bird Conference on Andean Textiles, ed. Anne Pollard Rowe (Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum, 1986), p. 88

Additional resources:

Anne Paul, Paracas Ritual Attire: Symbols of Authority in Ancient Peru (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990)

Anne Paul, ed. Paracas Art and Architecture: Object and Context in South Coastal Peru (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1990)

D.A. Proulx, “Paracas and Nasca: Regional Cultures on the South Coast of Peru,” in The Handbook of South American Archaeology, eds. Helaine Silverman and William H. Isbell, 563–585 (New York: Springer, 2008)

Paracas Textiles: An Introduction

A Desert Necropolis in Peru

At around the same time that Chavín culture flourished in the highlands, the Paracas peninsula on the southern coast of Peru witnessed the rise of a new society of farmers and fishermen. The Paracas culture (c. 700 B.C.E.–200 C.E.) is best known not for its monumental architecture, but for what lay buried below the ground: a necropolis of hundreds of miraculously preserved mummy bundles. The Paracas mummies were buried in two different types of burial chambers. The Paracas Cavernas (cavern) pits were small bottle-shaped shaft tombs, while the Paracas Necropolis crypts were large mausoleums fitted with masonry walls.

Located within these tombs were mummy bundles wrapped in sumptuous embroidered textiles, some reaching up to four feet in circumference. The textiles ranged in quality from rough swaths of undecorated cloth to finely embroidered mantles. Mummies were also buried with offerings of food and jewelry to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. The types of textiles and offerings associated with a mummy bundle shed light on the individual’s social status; the larger and more elaborate the bundle, the higher social standing the person held during his or her life.

Paracas textiles provide some of the most stunning examples of pre-Columbian Andean fiber art. Close examination of Paracas textiles reveals a great deal of information on the sophisticated embroidery techniques developed by Paracas artists, their system of textile production, and their belief systems.

Material

Paracas embroidered cloths were made out of cotton and camelid fibers. Cotton is a local coastal crop that would have been readily accessible to Paracas artists. Camelid (related to the camel family) fiber, on the other hand, derives from llamas, alpacas, and vicuñas indigenous to the highlands.

Paracas weavers would have procured camelid fiber through long-distance trade. Cotton would have been used for weaving the ground cloth while the silkier, high-quality camelid threads were typically used for the embroidery.

Style and techniques

Linear style

Linear Style textiles are embroidered cloths that feature repeating geometric designs. Many Linear Style textiles appear to be woven because the embroidery covers nearly the entire surface area of the ground cloth. Paracas textile specialists would embroider designs on a grid pattern instead of stitching along the contours of the design. In other words, the embroiderers would stitch each color separately in a linear fashion until the entire composition became filled in with lines. This required a great deal of planning and visualization to achieve the final product. Paracas textile specialists employed an apprentice system in which less experienced embroiderers produced designs alongside those of experts in order to mimic their designs and techniques. One single cloth could bear the work of many different hands with varying levels of expertise.

The Block Color style, on the other hand, was made by stitching outlines of shapes and then filling them in with broad areas of color. Block Color style tends to be less geometric than Linear Style, and has more open spaces between motifs. Both Linear and Block Color styles were being used during the same time period.

Symbols

Felines, serpents, birds, and fish dominate the Linear Style symbolic repertoire, while human figures are added to the subject matter of Block Color textiles. Unlike what we see at Chavín, Paracas symbolism mainly consists of local wildlife, including fish, pampas cats, falcons, and hummingbirds.

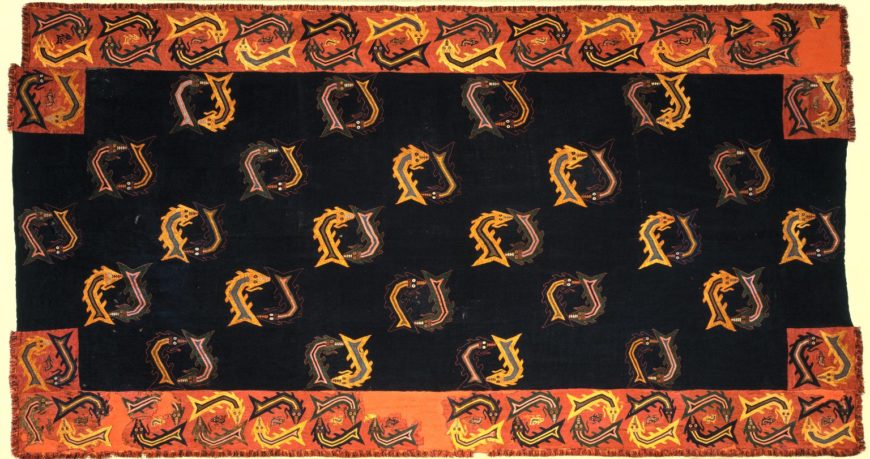

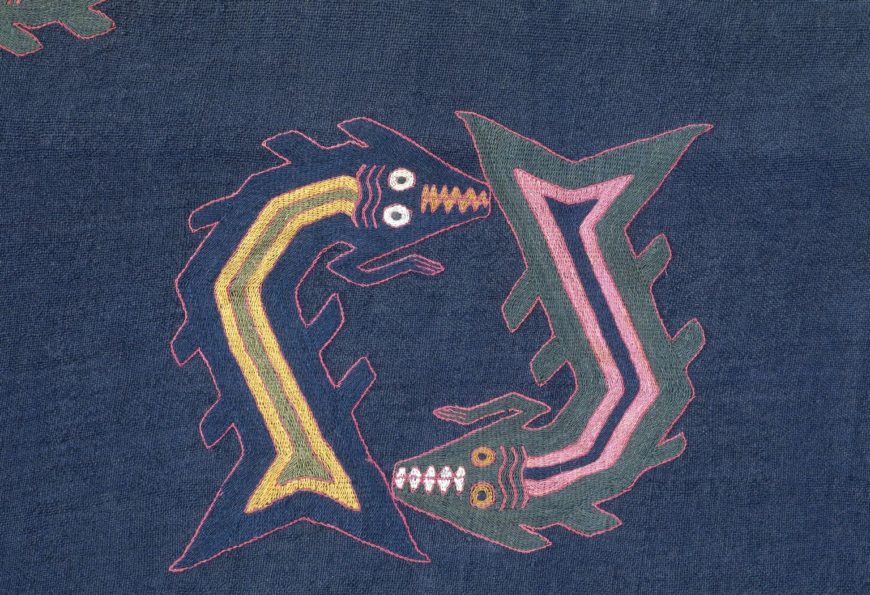

In the Double Fish Mantle we see a series of paired fish transposed to one another, with each head facing the tail of the other. Art historian Mary Frame suggests that they represent sharks due to the appearance of gills behind the eyes. In the orange border, smaller sharks are enclosed within the protected space of their connected bodies, and may be a reference to fertility and reproduction. The Paracas embroiderers depicted a range of aquatic and terrestrial life in their textiles, providing a comprehensive picture of the peninsula’s thriving ecosystem.

Paracas textiles contain standardized geometric, linear representations of animal motifs. The repeating images have a rhythmic character and usually remain faithful to the pattern. The designs are dense and compact, and bear little distinction between foreground and background. In the Double Fish Mantle, the fish motifs are arranged symmetrically within the mantle, with four pairs of fish embroidered along the long edges, followed by a row of five pairs, with six pairs along the center of the mantle.

While the number and distribution of the fish pairs conform to a set pattern, a great deal of diversity can be found in the details of the embroidery. Some are green, blue, and pink; others are black, pink, and brown, while others are yellow, blue, and brown. The specific color combinations vary across the composition and do not fit into any discernible pattern. The subtle interventions made by the embroiderers, which break the pattern through the unsystematic distribution of colors, lend the mantle a powerful visual dynamism. The orange borders of the mantle offer a pop of color and also feature a slight variation of the fish motif.

Use

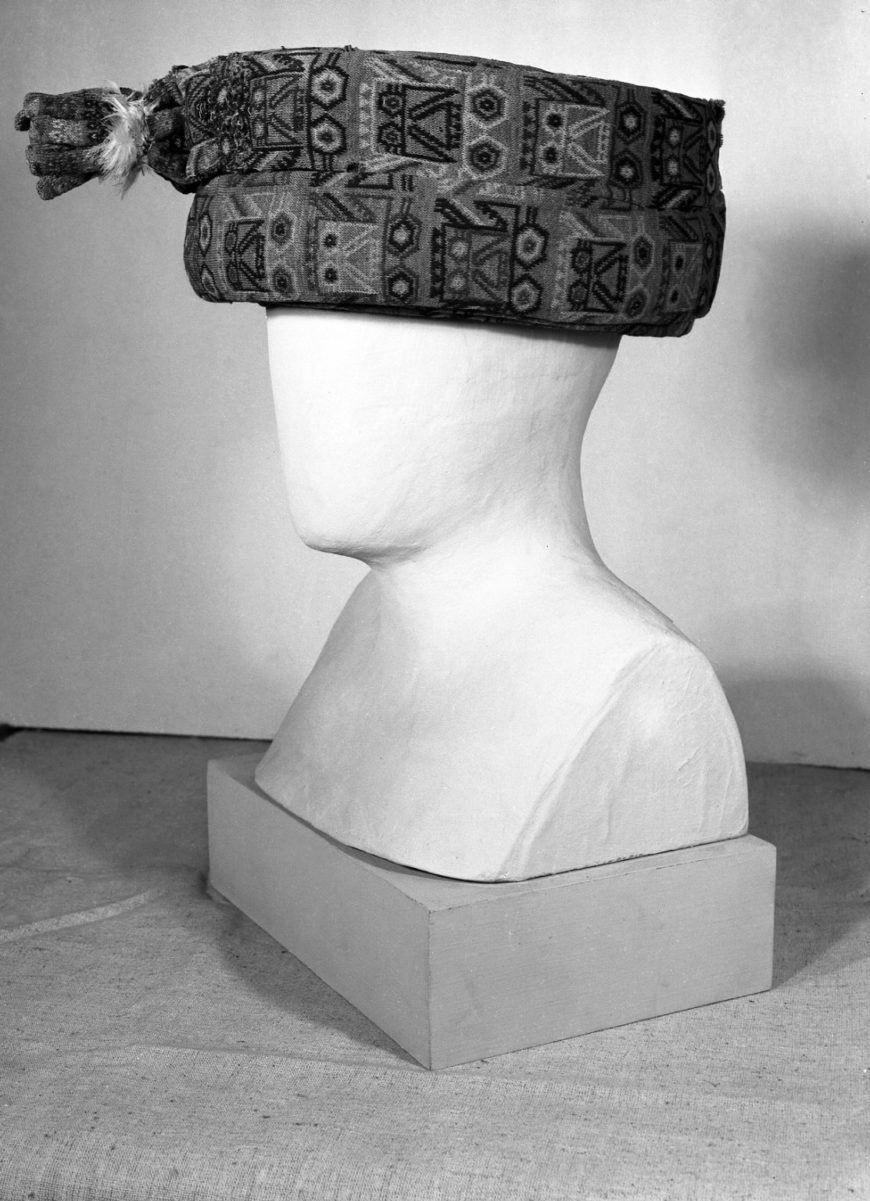

Paracas embroidery adorned a number of different types of textiles and garments. Everyday clothing such as hats, and ponchos often contained embroidered sections executed in the linear style.

The most elaborate embroideries can be found in mummy bundles. Long swaths of cloth embroidered in the linear style were wrapped around the deceased to create a bundle, some measuring up to 85 feet in length.

Additional resources

Read more about Andean textiles at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rebecca R. Stone, Art of the Andes: From Chavín to Inca (London: Thames & Hudson 2012)

Anne Paul, “Paracas ritual attire: symbols of authority in ancient Peru,” Civilization of the American Indian series (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990)

Anne Paul, Paracas art & architecture: object and context in South Coastal Peru, 1st ed (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991)

Helaine Silverman, “Differentiating Paracas Necropolis and Early Nasca Textiles,” Andean archaeology II: Art, Landscape, and Society, edited by W. H. Isbell and H. Silverman (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2002), pp. 71–105

Paracas Supernatural Bird Mantle

The Transcendent Bird

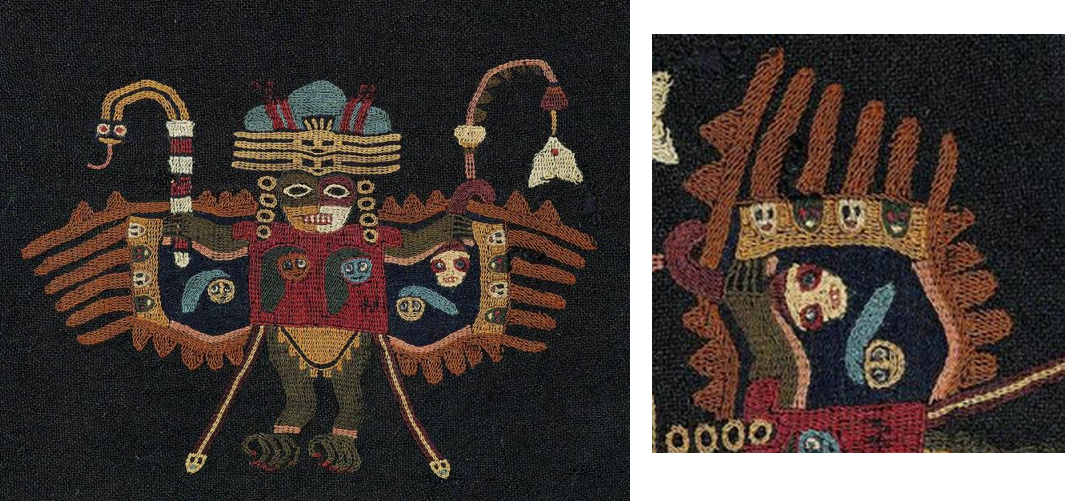

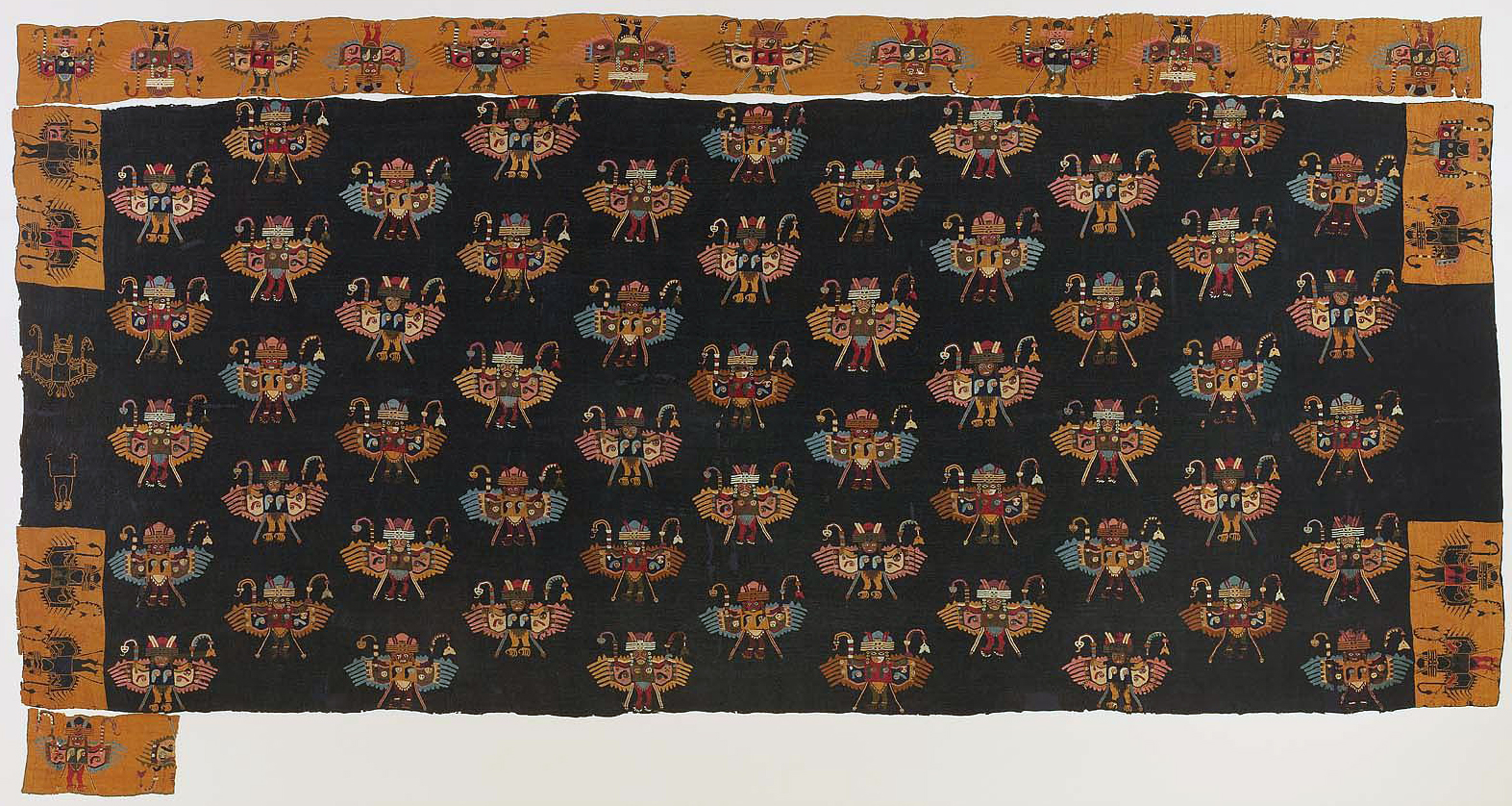

Birds and winged creatures have often been tasked with duties of great symbolic importance in human culture. From harpies to storks, interfacing with the spirit realm and ferrying precious items and messages are just a few of birds’ mythic and folkloric roles throughout time and place. In the Peruvian south coast, a village culture now known as Paracas (c. 700 B.C.E. to 200 C.E.) created a version of the supernatural bird that demonstrates enduring elements of Andean art—a bird with outstretched wings, composite imagery, and symbolic heads—in a distinctively Paracas visual style.

This being was recorded in embroidered camelid fiber upon a large funeral mantle, one layer of many textiles making up an elite mummy bundle preserved for some 2,000 years in the Paracas Necropolis cemetery on the arid coastal peninsula which gives the culture its name. When discovered and unwrapped, this textile (from the 1st century C.E.) revealed colorful, flying human/bird figures dressed in elaborate costume and possessing of an intriguing array of accessories.

Anatomy and Costume

The avian figures are rendered in the final stylistic phase of Paracas Necropolis embroidery that art historians refer to as the Block Color style. The placement of the figures in a checkerboard pattern across the mantle’s ground cloth and in alternating up/down poses on its border is typical of Block Color compositions. The inherent freedom of embroidery, a technique in which thread is stitched upon the surface of a woven cloth, made it possible for Paracas artists to create complex, multi-colored figures. Four different combinations of red, pink, blue, dark green, yellow, and soft green stitches articulate a headdress with frontal bands and dangling ornaments, colorful faces (possibly wearing masks), and fringed tunics. They carry banded staffs curving into serpents in one hand, curving staffs with fringe ending in floral or fishtail ornaments in another. Fantastical elements, such as avian toe-and-talon feet and snake emanations, place the figure firmly in the realm of the supernatural.

While the color and curvilinear style are unprecedented in Andean art, serpent/bird combinations and composite imagery are found in Andean art as early as the Cotton Pre-Ceramic period (c. 3000 B.C.E.–1800 B.C.E.) in the Huaca Prieta twined textile and in stone at the Old Temple of Chavín de Huantar (c. 900 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E.). The Paracas human/bird’s wing feathers also double as heads, another example of characteristically Andean composite imagery.

The Symbolic Power of Heads

Figures clutch a head by its hair, two heads are placed on the front of the body, and one is placed within each wing. Heads are a frequent motif appearing in all phases of Paracas art, and caches of severed human heads have been found within some of their burials. Numerous archeologists, beginning with Julio C. Tello in the early 20th century, believed severed heads were trophies taken in conflict. This interpretation has been supported by the fact that many heads, some of young men, were buried with ropes (presumably for transport and display) still attached to their skulls.