4.6: Structures and Sculptures (1800-1900)

- Page ID

- 120752

Introduction

With the Industrial Revolution came the ability for mass production of goods and materials, extensive manufacturing facilities, an abundance of coal and power, transportation systems, and the accumulation of money by a few. Steel was a vital part of the revolution, the main component in buildings, railroads, and shipping. Gustave Eiffel was able to have steel manufactured to support his tower because of steam power to mine the raw materials and run the manufacturing plants. William Morris designed patterns for textiles based on new methods of dyeing, weaving, and manufacturing materials. Sculptors no longer relied on money from the government or religious sources; private citizens also supported the arts.

Gustave Eiffel

Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) was a French engineer who designed bridges and viaducts for different projects in France. He graduated from one of France's prestigious engineering schools, then worked as a researcher in a company where he created a new method of supporting the railroad's bridges. He was also hired to design girders for a new gallery, studying cast iron properties and applying his theories to casting. His reputation grew, and he became one of the leading engineers in France, employing his innovative engineering theories to bridges and buildings. To support the new proposed exposition in France, engineers designed a preliminary concept for a tower. Eiffel endorsed the plan and then acquired the patents and rights to the design.

After a commission for the tower selected Eiffel's design, he started working on the tower (4.6.1), and the critics began to object. Some of the important artists sent a letter stating:

…To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of Les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe; all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years…we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.[1]

.jpg?revision=1)

Eiffel responded with a discussion about the pyramids and their grandeur on the aesthetic impact of architectural structures. He argued his tower would be the highest thing ever built and look as beautiful in Paris as the pyramids did in Egypt. Eiffel built the tower during the time of the industrial revolution when inventions were creating new societies, trade grew, and lives were altered under increasing prosperity. Many believed Eiffel's tower was the crown.

The engineers drew over 5,000 drawings for the tower, more than 100 workers made the parts, and another 130 assembled the 18.000 pieces at the site. The foundations had to be dug by hand for the four legs of the tower. The completed tower used over 7,000 tons of iron in its design to account for the resistance to wind forces. He believed metal's resistance to the movement was superior to wood or stone. When the second level was completed in May 1888 (4.6.2), Eiffel took officials to the level, amazing them with the view. When it was completed, the tower was the highest structure in the world until 1930, and the Chrysler Building in the United States was built.

Auguste Rodin

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), whose parents were ordinary working people in Paris, trained early in art and anatomical structures and then worked as a sculpture apprentice. When he went to Italy, he studied the work of Michelangelo, a work that influenced how Rodin created his sculptures. Rodin's work did not follow the traditional decorative or mythological ideas of sculpture; instead, they were realistic and complex, posed in emotional positions. He positioned multiple models in his studios, forming quick clay models that he used later to make plaster casts and then bronze or marble statues. As time passed, he did not follow traditional positions for the body or attachments for parts of the statue; the surfaces were rough, often pock-marked. Some historians believe he is the most significant sculptor of modern times.

The Gates of Hell (4.6.3) was his first government commission. He sketched multiple ideas, even making clay models, all based on the Divine Comedy by Dante. When it was time to deliver the giant 6.4 meters high doors, Rodin was not finished with them. He made clay models for each of the different figures on the gates, which continually dried before he was finished, and finally removed each one, making plaster casts to preserve each figure. This also allowed him to remake, enlarge or move each of the figures, some of them only 15 centimeters tall and ranging up to one meter high. The plaster casts of each statue became the basis for individual sculptures and appeared on the gates. The final gates were not cast for over thirty years, and were never cast in bronze during Rodin's life, only cast later after his death.

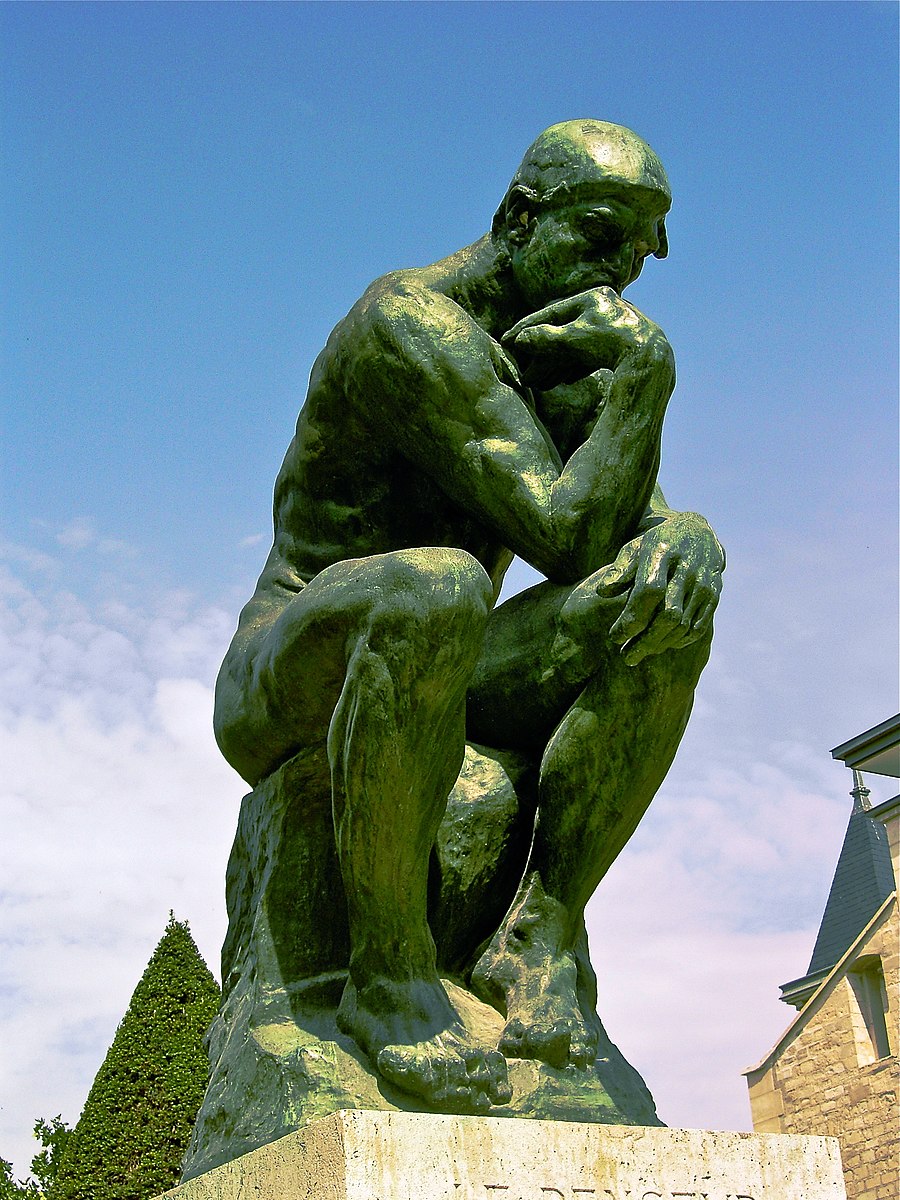

The Thinker (4.6.4) was part of the Gates of Hell, not originally a standalone sculpture. As part of the gate's panel, he sits at the top of the lintel on the door, gazing down. Rodin talked about the statue as a poet, an image of a creative person, and the agonizing over his world. Rodin described him as "What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils, and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back, and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes."[2] The Thinker has been cast multiple times from Rodin's original clay sculpture along with newer castings, not part of the original image.

The French government wanted public monuments to honor French patriots of the past and commissioned Rodin to build the tribute. One theme the government chose was based on six wealthy men from Calais who volunteered as hostages to one of the English kings to stop the siege on the town. The government asked Rodin to make a statue of the group leader; however, he made a model of all six of the men, an image the government accepted, The Burghers of Calais (4.6.5). Rodin worked on each person individually, not following traditional heroic settings or images on a pedestal with other allegorical images. Instead, the men portrayed their agony and pain in the situation. They were all installed on the top of a pedestal instead of standing individually as Rodin wanted. Twelve castings of the sculpture have been made, including the one at Stanford University (4.6.6), where the men each stand alone as Rodin originally intended.

Camille Claudel

Camille Claudel (1863-1943) was from northern France and was recognized at an early age for her artistic talent and beauty. She studied sculpture at an academy and had her studio until Rodin asked her to be his assistant. One advantage this opportunity gave her was the ability to study the nude figure and its anatomy; a subject women could not study at the time. During her time in Rodin's studio, she helped model some of his sculptures while developing her career.

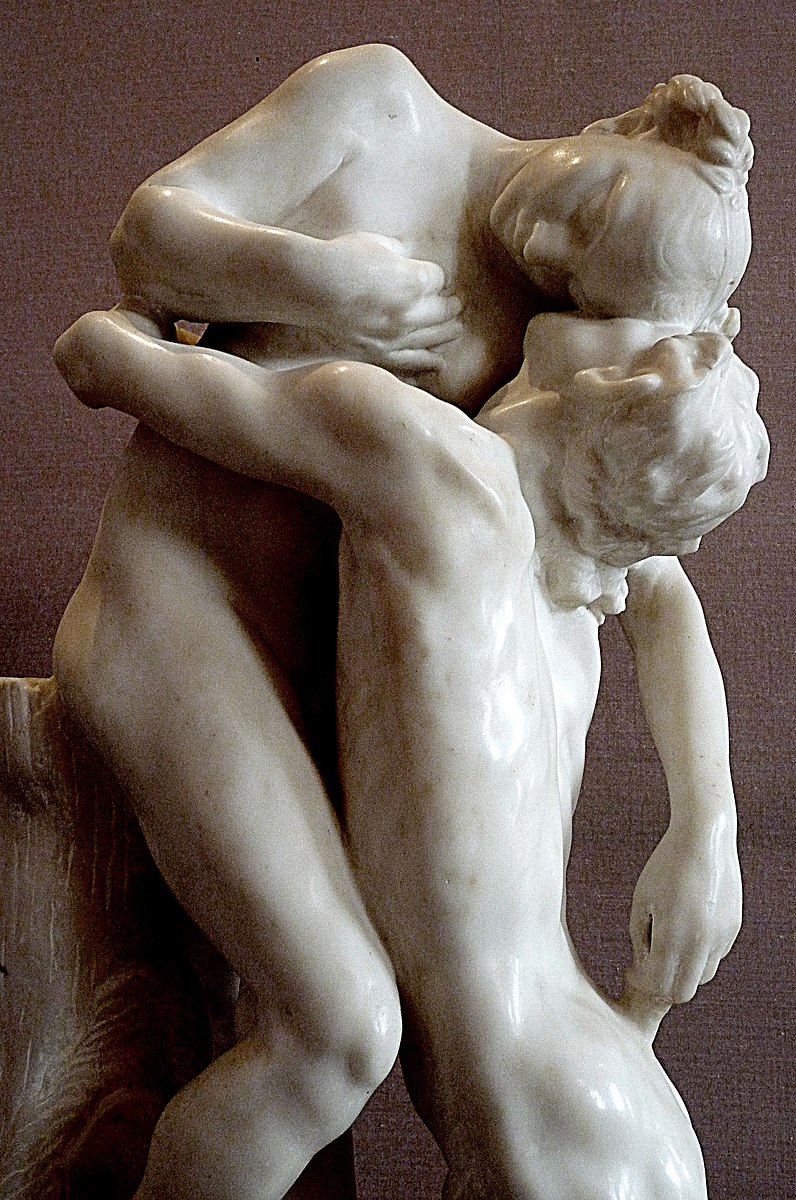

Her relationship with Rodin was stormy, an affair lasting ten years, hard work and harsh clashes, and Rodin returned to another woman he married. She finally left to work on her own. Others criticized her work and the press, partly based on her assumed position with Rodin as not only a teacher but her lover. As she was working, Claudel developed symptoms of delirium and dementia, and she was committed to an asylum, stopped working, staying there for thirty years until her death. Vertumnus and Pomona (4.6.7) was based on an old play from India about a woman's reunion with her husband when the magic spell was removed. Claudel tried to obtain a commission from the state and was refused; however, a private citizen commissioned the work, carved in white marble and standing on a base of red marble.

The Age of Maturity (4.6.8) originally was a commission by the French government that was canceled after the plaster version was created and before a bronze could be cast. Later two bronze statues were cast, and the plaster was destroyed. The sculpture has three figures, an older man who is in the embrace of an older woman as the kneeling younger woman reaches out. Many view this as a statement of life, youth aging into maturity, and finally death, while others interpret the statue as Rodin abandoning Claudel as he returns to another lover. Rodin did not like the work, and some think he influenced the commissioner to reject the sculpture.

Daniel Chester French

Daniel Chester French (1850-1931) is one of America's leading monuments sculptors. Born and raised in the New England area, he studied art and sculpture, earning a few commissions for public art. In his late twenties, the French went to Italy to study, not following the path others took to study in Paris. He returned to America, created several commissions, and then went to Paris for a year to study the French methods.

When he returned, one of his major commissions was the bronze memorial statue for Dr. Gallaudet, who founded the school for the deaf in Washington D.C. The sculpture (4.6.9) portrays Dr. Gallaudet seated next to the student Alice Cogswell. He uses sign language to spell the letter 'a' to the girl who copies him, representing a new method of education for those who are hearing.

French seldom sketched his ideas, preferring to create clay models. He was commissioned to make the statue for a new memorial to honor Abraham Lincoln (4.6.10). The base and columns made to enclose the statue were designed by Henry Bacon, whom the French worked with closely. The original size for the statute of Lincoln was planned to be 3 meters high; the size French made for the clay model. When it was taken to the site, he knew the size would not work and reworked the plan, a 5.8-meter-tall Lincoln, one of the most iconic statues in the world. French made the final sculpture from 28 blocks of marble; his chisel marks are still visible in some places. Lincoln sits, gazing straight ahead, a solemn look on his face as his expressive hands rest on the chair, the American flag draped over the back of the chair.

Harriet Hosmer

Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908) was one of the first American women to become a professional sculptor and was thought of as the eminent female sculptor of the period, paving the way for other women sculptors. As a child, her mother and three siblings died from tuberculosis, and because she was considered feeble, her father encouraged her to try different sports to build her strength. She became an expert in riding, rowing, swimming, and skating. She was skilled in working with clay, modeling figures, and studying anatomy with her father, a physician. Her first attempt at sculpting was successful; she went to Rome to study, knowing America did not have any schools where women could work with marble or use live nude models.

In Rome, she lived and worked in a colony of different writers and artists, including several American female sculptors who worked with marble. The writer Henry James called them "a strange sisterhood of lady sculptors'" and "the white marmorean flock,"[3] and Hosmer was considered their leader. She had a series of relationships with other women and ended with a commitment to Lady Louisa Ashburton for twenty-five years. When Hosmer returned to America later in life, Hosmer became an activist in the women's rights movement and a friend of Susan B. Anthony. In Hosmer's later years, she spent time on different inventions and had a patent on the process she believed changed limestone into marble.

The majority of her work was based on tragic women from history, mythology, or literature. Zenobia in Chains (4.6.11) was one of her early works and financial success for Hosmer. The sculpture depicts the queen in the third century who was captured by the Romans, wrapped in chains, and paraded through the streets. Her clothing is layered in exquisite folds, and the details of the chain demonstrate Hosmer's ability to work with the complexity of marble. At the time, some critics did not believe a woman could create the complex, detailed statue standing 213.36 centimeters high. They thought she would not have enough power in her arms and hands to carve the marble.

The Sleeping Faun (4.6.12) depicts a woodland spirit inspired by the mythological forms from ancient Rome. Hosmer had a unique sense of humor reflected in the mischievous smile on the half-goat and half-human satyr who tied the faun's clothing to the tree stump, the perfect image of Hosmer's mastery of the neoclassical style. One critic stated, "If it had been discovered among the ruins of Rome or Pompeii, it would have been pronounced one of the best Grecian statues."[4]

When Hosmer was in Rome, she met the well-known poets from England, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Hosmer asked if she could model their hands, and they agreed. She kept the hands (4.6.13) exactly are they were formed in the mold to maintain the textural characteristics of the work. Each person's hand is identifiable by the size of their hand and the cuffs of their shirts as it appears on the wrists. The hands were initially made in marble as a present for her niece.

Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907), the first woman of her heritage to become an internationally known sculptor, was born in New York, the daughter of a free African-American father and her mother from the Native American Anishinaabe. Her parents died when she was nine, and she lived with different relatives, frequently helping her aunt weave Ojibwe baskets to sell to tourists. Her older brother paid for her tuition in high school, a place she left after three years stating, "Until I was twelve years old I led this wandering life, fishing, and swimming…and making moccasins. I was then sent to school for three years in [McGrawville] but was declared to be wild--they could do nothing with me."[5] Abolitionists sent her to Oberlin College to study art, one of the few universities to admit women or people of differing ethnicities. However, she encountered multiple problems during this period, finally leaving a semester before graduating.

Lewis went to Boston in 1864 to pursue her dream of becoming a sculptor. With the help of the abolitionists, she worked with another artist before opening her studio, successfully making statues. Lewis went to Rome to further her career with her success in hand, staying there for much of her life. She expanded her neoclassical style to include themes from her heritage. Lewis was part of the sisterhood of lady sculptors, joining the other female sculptors in Rome.

Lewis frequently was inspired by her Native American and African American background to define the subject matter of her work. Based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem, The Song of Hiawatha, she honed several marble sculptures of Hiawatha (4.6.14) and Minnehaha (4.6.15). The two cabinet-sized busts wore romanticized Native American dress, characterizing the two ill-fated lovers. The Hiawatha in Wadsworth's poem was considered to be Anishnaabe (Chippewa), the same tribe as Lewis' ancestors.

Lewis depicted Cleopatra (4.6.16) at the time of her death from the poisonous snake's bite. Cleopatra is dressed in regal clothing, dying as she sat on her throne. The sphinx heads on each side of the throne symbolize her two twins. Most sculptors portray Cleopatra shortly before death, while Lewis decided to present Cleopatra after death, a concept criticized as shocking and repulsive. When the statue was first shown in America, she got rave reviews. Shortly after the statue's debut, it was presumed lost until a century later, appeared "at a Chicago saloon, marking a horse's grave at a suburban racetrack, and eventually reappearing at a salvage yard in the 1980s."[6]

Anne Whitney

Anne Whitney (1821-1915) was born in Massachusetts to a family of abolitionists who fought against slavery and for women's rights. She was a writer and then studied sculpture, opening her studio. When Whitney was only twenty-five, Whitney started a school for girls in Massachusetts. She moved to Rome after the civil war, studying both bronze and marble and using nude models who were male. She also was considered part of the sisterhood of women, associating with Edmonia Lewis, Harriet Hosmer, and others before she returned to America.

Early in her career, Whitney and all women were limited in what they studied, unable to take classes in life drawing or see plaster casts of humans in a coed classroom. If women wanted to visit an art gallery, any forms of nude men had their genitalia covered. So, she began making busts, the shoulders and head a safe form for female artists to pursue. A local shipowner commissioned her to make a sculpture of his daughter, Laura Brown (4.6.17), who was two or three at the time. The innocence of the young girl is evident in her half-smile and slightly plump body. Whitney is quoted as saying, "The likeness is good and the modeling I think the best by far I have done. It has been a great labor. The perpetually ranging curves of a child's face, the impossibility of getting a half moment's fixed look, and this child's expression being the most mobile…I ever saw, made altogether the work for some time almost a despair."[7]

On one of her journeys to Italy, she studied French sculpture procedures, using the methods to create her bust of Le Modele (4.6.18), based on concepts of Realism. She fashioned the image of a peasant woman, exaggerating the character of her wrinkles. The statue was cast in bronze, the in-depth details reflecting shadows and light.

Charles Sumner

A Harvard graduate, Charles Sumner (4.6.19) was a fervent abolitionist who became a senator from Massachusetts and worked on the legislation to abolish slavery. After he died, the city of Boston wanted to erect a statue in his honor, asking for artists to apply for the commission. Whitney had devoted herself to social justice and designed a memorial sculpture of Charles Sumner for the contest. The selected winner portrayed Sumner sitting on a seat, holding a book in his hand while attentively looking out over the area. The committee thought it represented the thoughtfulness and spirit of Sumner and Whitney won the national contest. However, someone told the committee a scandalous fact: a woman proposed the statue, and the committee selected the second-place design. "She was denied the commission after the judges discovered she was a woman. No woman, said the learned gentlemen, should attempt to model a man's legs: it was indelicate, and furthermore, it would never be successful."[8] The plaster model she made was stored away for over thirty years until 1902, when an anonymous donor had the bronze version of the statue cast and moved to the gate at Harvard.

William Morris

William Morris (1834-1896) was an artist and designer who changed the styles and fashions of the era. Coming from a wealthy family, he was educated privately and continued to Oxford. Morris founded a firm with friends, a successful company specializing in wallpaper, fabric, some furniture, even stained-glass windows, and changing interior decoration designs. Morris was also a social activist who led him to start a publishing company, writing and illustrating many of their books.

Morris aspired to construct a home in a rural area near London, surrounded by orchards, hills, and streams. He worked with Philip Webb as a co-designer for the house with Medieval and Gothic influences, designing an early version of the Arts and Crafts style. The Red House (4.6.20) was two stories high, made of brick with red tiles on the pitched roof some say resembled witches' hats. The different windows were defined separately in multiple styles for each room instead of reflecting an exterior symmetry. The house was severe in design and furnishings, unlike the excessive Victorian ornamentation of most buildings. Morris designed everything for the interior: fixed furniture, drapery, wall coverings, tableware, and even candlesticks. When Morris and his family lived there, he recognized the problems with the house; the north-facing was exceptionally cold in winter, the isolation made it hard for physicians to visit Morris, who had health problems, and the commute to the railway station was long. He sold the house after living there for only five years. Currently, the house has been restored and is part of the National Trust system in England.

Morris wanted his designs to be historically based and studied historical methods of dyeing and printing. He also based multiple designs on the hedgerows and gardens that grew in England. He designed over fifty types of wallpapers, designed as a radical departure from the Victorian styles of the day. Snakeshead (4.6.21) is printed on cotton, showing the balance and subtle formation of the natural form. During his studies, he learned the techniques used in India and how they strongly contrasted the colors and converted three-dimensional designs to flat patterns. He also changed the way dyes were used, moving from the chemical dyes to organic ingredients, for example, using walnut shells to make a brown color. Because the designs were complex, the fabric had to be double woven to achieve deep, intricate colors.

One of Morris's first tile designs (4.6.22) was for his Red House, leading him to add ceramics and tile to his business line of products. He used the same ideas on the tile as he did for fabric, well-formed and symmetrical designs.

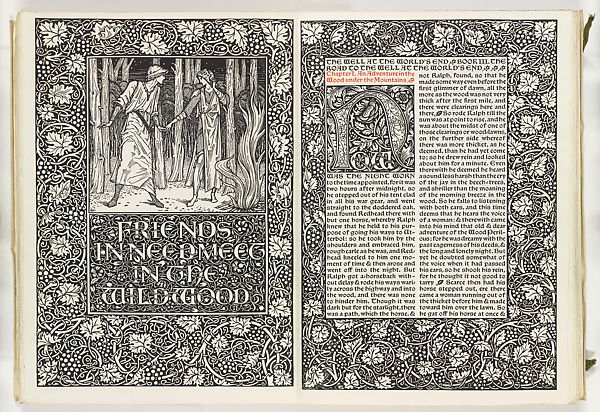

Morris was also a writer; most of his early work was based on his political views. He wanted to reform how books were made and bring artistry to the printed page, so he started his own publishing company. Morris wrote a book based on his imagination, The Well at the World's End (4.6.23), one of the first books considered fantasy fiction, not just about dreams or travels around the world, but another invented world. He had his partner do the illustration, and Morris designed the complicated border using grapes, vines, leaves, and a large typeface.

Charles Edenshaw

Charles Edenshaw (1839-1920) was born in the Skidegate, a Haida village in British Columbia, Canada. His lineage was from the Haida matrilineal organization, and his birth name: Da.a xiignag. He was known for carving wood and argillite, a rock similar to shale; fractured, veined and generally deformed. However, it does not foliate like shale. Edenshaw was considered a master of the formline design system; the U, S, and ovoid forms were used as outlines and design elements in Northwestern indigenous art. Form lines change thickness when they flow around corners, and interconnected form lines create the design. The form lines are two-dimensional on flat surfaces and three-dimensional on totem poles or masks.[9] "Edenshaw's name has become synonymous with classic Northwest Coast style, and his work has inspired nearly every serious artist in the region."[10]

In the 1850s, the indigenous populations in the Pacific Northwest were devastated by smallpox. The Canadian government outlawed the ceremonial raising of immense totem poles, leaving the native people unable to continue traditions, including making totem poles. Edenshaw started carving model totem poles, carrying on the tradition in a smaller format, bringing the imagery and artistic conventions to life and maintaining their cultural identity and oral history for the next generation. He used argillite to carve the model totem poles (4.6.24, 4.6.25), a significant volume of his work. By the end of the 1800s, Edenshaw's model totem poles became the characteristic example of argillite carving.

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\): Model Totem Pole 1 (1885 argillite 66.7x11.7cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\): Model Totem Pole 1 (1885 argillite 66.7x11.7cm) Public Domain

The industrial revolution changed Europe and America with mass production of products and new types of materials available. Expanded populations had more money; towns and private citizens could afford to purchase art creating a marketplace for artists. During this period, female artists started to realize their potential and their right to have an identifiable career in art. All three sculptors in this section used bronze to produce the finished art sculptures and the original cast could be used over and over to create the same piece of art. Producing multiple sculptures allowed artists to increase their commercial productivity.

[1] Huskinson, L. (2018). Architecture and the Mimetic Self, Routeledge. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=6HRUDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT172&lpg=PT172&dq=To+bring+our+arguments+home,+imagine+for+a+moment+a+giddy,&source=bl&ots=YBcS0hz0Co&sig=ACfU3U1bgiqcqQDrC-TfdjTY238YJQBs2A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj2zfK40I_iAhW0MX0KHentBPUQ6AEwCXoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=To%20bring%20our%20arguments%20home%2C%20imagine%20for%20a%20moment%20a%20giddy%2C&f=false

[2] Retrieved from https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.1005.html

[3] Retrieved from https://outlook.wustl.edu/2008/fall/hosmer.htm

[4] Bradford, R. (1912). The Life and Works of Harriet Hosmer, The American Sculptor, The New England Magazine, Vol 45. P. 268.

[5] Buick, K. (2010). Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject, Duke University Press, p. 111.

[6] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/death-cleopatra-33878

[7] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/laura-brown-27650

[8] Payne, E. (1971). Anne Whitney: Art and Social Justice. The Massachusetts Review, 12(2), 245-260. Retrieved June 12, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25088108

[9] Retrieved from https://www.sealaskaheritage.org/sites/default/files/Sealaska%20Heritage%20Formline%20Art%20Kit%20ONLINE%20low%20res.pdf

[10] Retrieved from https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/totems-to-turquoise/master-artists/charles-edenshaw