4.7: American Naturalism (1800-1900)

- Page ID

- 120753

Introduction

Significant westward expansion originated in 1803 when Thomas Jefferson signed the Louisiana Purchase, paying France fifteen million dollars for land west of the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border. France only controlled a minimal amount of the region, most of the area inhabited by Native Americans. The United States essentially purchased the anticipatory ability to take the land by treaty or conquest. After the purchase was signed, Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark on their famous journey to the Pacific Ocean, opening new territory. Artists also traveled with other explorers, painting the wonders and people they observed in the westward expansion. Out in the new spaces were opportunities for cheap land, minerals, and other financial incentives leading to the Indian Removal Act, the Trail of Tears, and other acts bringing disease and warfare to the tribes, pushing the native peoples further west onto reservations.

The concept and necessity of expanding westward were idealized in Manifest Destiny, the principle of the responsibility to conquer, inhabit and prosper. Artists frequently romanticized the settlers, cowboys, miners, soldiers, explorers, traders, and others who were part of the movement into the promised land. The discovery of gold in California brought thousands of people westward, expanding the boundaries of statehood. The railroads crisscrossed the landscape, moving people and expanding trade routes. In the middle of the movement across the west, the Civil War raged. The conflict of the north and south added to the migration of people fleeing the war into the new lands. When the war ended, many soldiers became part of the troopers in the west, patrolling the western regions, escorting the continual parade of settlers, and fighting the native tribes.

Part of the lure of the west was the incredible scenery of the extreme mountain peaks, roaring waterfalls, immense trees, and rushing rivers, all inspirations for an artist who traveled the regions. Unfortunately, some people wanted to exploit the natural resources; mine the mountains, cut the trees for lumber, level the ground for agriculture, remove the native animals for cattle or build cities. Artists who journeyed through the west painted incredible sights and images of spectacular beauty. Early writers composed stories and poems of the wonders they saw, all helping to develop a concept of national pride in these untamed wilderness areas in the people of the east and government officials. In 1864, President Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant Act, ensuring the protection of Yosemite Valley, the precedent for the establishment of national parks. This was the first time the federal government specified land saved for preservation and use by the public. In 1872, President Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act creating the first national park for the benefit of Americans—except the Native Americans who lost their natural hunting grounds. 1,221,773 acres were part of the park, changing the policy of transferring the public lands to private ownership.[1] Future presidents followed and set aside other lands for the public and ecological preservation.

Hudson River School

As the new country developed, the Hudson River school became the first well-known artistic community, a group of landscape painters in New York. The school was attributed to Thomas Cole, not a founder but the first teacher, helping to develop the new style after he toured the country, saw the westward expansion, and was inspired by the vistas he saw in the frontier landscapes in the east. Many of the artists were initially inspired by the landscapes of England by John Constable. Their first focus was on the mountains of the Catskills, trying to capture the beauty of remote, unsettled places, traveling the region, and sketching the rivers, trees, and mountains. The practice of sketching a scene outdoors, using oils for the base of the sketches, and finishing the landscape details in the studio, became the new methodology. How the natural light illuminated the view was an essential element of the painting.

Thomas Cole

The work by Thomas Cole (1801-1848) was one of the first paintings of the American landscape, uniting the wilderness in a pastoral setting. Although born in England, he migrated as a teenager and worked engraving wood, then painting portraits. He went to Europe to study on the Grand Tour before returning, impassioned by the landscapes of the United States. He first drew the view in his sketchbook, noting parts he wanted to remember, and completed the painting in his studio. The painting, The Oxbow (4.7.1), became an icon, the focus of a methodology, and an image copied throughout time. Cole was not interested in how the lands were misused; instead, he "juxtaposes untamed wilderness and pastoral settlement to emphasize the possibilities of the national landscape, pointing to the prospect of the American nation."[2]

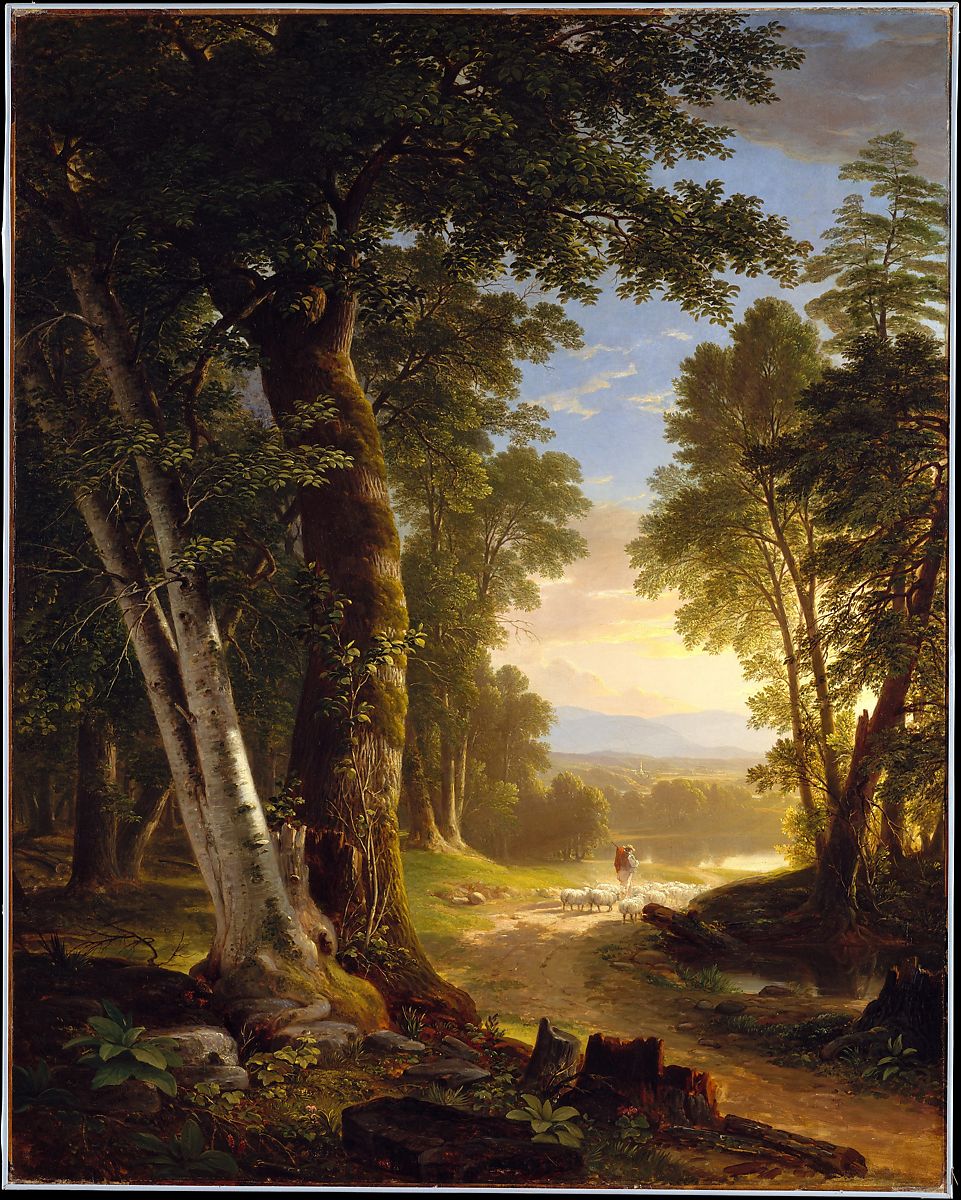

Asher Durand

Asher Durand (1796-1886) started as an engraver, building his reputation as an artist before painting generic scenes and portraits. Attracted to Cole's work of nature, he went with him to sketch in the Adirondacks and converted to landscape painting. Durand painted The Beeches (4.7.2), sketched the trees plein-air with oils on-site, and finished in the studio. He showed the beauty of the landscape, each tree meticulously produced, the long pathway leading to the phenomenal light in the sky demonstrating the natural setting of the new American landscape. The trees created deep shade in places while the sunlight shone through the individual leaves of the trees.

Frederic Church

Frederic Church (1826-1900) was a student of Thomas Cole and one of the most famous of the Hudson River painters. He traveled the mountains with Cole, and made and used sketches of different parts of the country to produce a composite landscape, not one local scene. Although many believed the natural landscape of the new nation was disappearing, he wanted to show the expansiveness of the country in an idealized view. New England Scenery (4.7.3) included multiple elements composed into one painting, a broad waterfall, a majestic mountain, rocks, and trees. He added a bridge with the Conestoga wagon appearing to be venturing into the frontiers of America and westward expansion. Church frequently emphasized the horizon, seen as stark mountains bisecting the paintings outlined against the lighter sky. Some critics praised his expansive scenes, while others thought his paintings lacked imagination.

John Kensett

John Kensett (1816-1872 was originally an engraver who wanted to be a painter and left engraving for Paris, studying painting and traveling throughout Europe. When he returned to America and became known for his portrayal of coastal waters. Kensett used delicate brushwork to produce the luminosity in the atmosphere of his paintings, the Hudson River Scene (4.7.4). The image displayed the Hudson River as it flowed through the mountains by Fort Putnam, along with the river bend and through the canyons, a common location for the artists. The contrasting and undulating view provided a variety of illuminated areas and dark recesses. He used light differently in the various terrains, deep shadows from the trees in the valley, sun shining on the mountains, and the light sky and was considered a master of luminism in landscapes.

Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) was born in Germany, migrating to the United States at two and then returning to Germany as an adult to study painting. The Alps provided the inspiration for landscapes, and when he returned to America, he traveled westward to the Rockies with an expedition surveying the territory for the government. In the dark recesses of the foreground, the expedition is camped in the meadows and surrounded by dark trees across the lower half of the painting The Rocky Mountains, Lander's Peak (4.7.5). The upper half is dedicated to light; the majestic Rockies jutting into the sky are hazy and blend into the bright sky. A small waterfall in the center of the painting leads the eye upward to the peak of the mountain. In the foreground is an idealized view of a Shoshone village, a part of the scene Bierstadt knew was ending as the bison was demolished along with the Shoshone way of life.

Robert Duncanson

Robert Duncanson (1821-1872) was an African-American born in New York and educated in Canada. He traveled to Europe, teaching himself to paint, and back in the United States, worked as a portrait painter, traveling around the mid-west. Some of his early portraits were part of an exhibition in Cincinnati; however, his family could not attend because of their race. As he gained experience, he became fascinated by landscape images. He received a commission from an abolitionist minister and gained a support network from abolitionist patrons. As part of the Hudson River school style, he painted detailed figures and trees with a fine brush and combined them with suggested elements of the broad expanse covered in the painting. He started in Ohio, painting landscapes of middle America, and was acknowledged as one of the foremost western landscape painters. One of his early landscapes, Land of the Lotus Eaters (4.7.6), was centered on Tennyson's paradise poem of the seduction of Ulysses' soldiers. However, Duncanson portrays the white soldiers lounging on the riverbank as dark-skinned men serving them in this painting. The painting brought wide recognition and even a showing in London, Duncanson winning praise as a skilled master. During the civil war in America, he went to Canada and helped start the Canadian movement to paint landscapes.

Natural History Illustration

When European explorers encountered unfamiliar lands, they needed proof of the flora and fauna they saw, considered exotic, oddities unknown in Europe. Explorers began to hire illustrators who accompanied them on exploratory voyages, documenting plants, animals, sea life, and reptiles they observed. One of the early illustrators was Sir Joseph Banks, a botanist and sailed with Captain James Cook on the Endeavour when he went to the Pacific islands, Australia, and New Zealand. Banks was one of the early, prolific illustrators who documented thousands of plants and wildlife. Sydney Parkinson also traveled with Banks on the Endeavour, and although he died of dysentery during the trip, Banks brought Parkinson's work back to England.

Charles Willson Peale, a well-known American artist, also had a gallery of his work for patrons to view, and hopefully, generate commissions. Some excavated mastodon bones were brought to his galley to paint; however, he found visitors were more interested in the bones than paintings. He began to collect different types of stuffed bird specimens and unusual bones, founding the original natural history museum in the United States. John James Audubon, always interested in nature, was inspired to establish his natural museum based on birds and other small animals.

John James Audubon

John James Audubon (1785-1851) was born in Hispaniola (now Haiti), his father the owner of the plantation and his mother a chambermaid who died when he was young. He was sent to France to stay at his father's home and educated in a wealthy environment, studying art and music and the history of the natural world. Even as a child, he was captivated by birds, drawing whatever he saw. At age 18, to avoid the Napoleonic Wars in France, he lived on his father's estate in Pennsylvania. He continued to study and draw birds as he married and opened a general store to support his family, an unsuccessful venture. After moving to New Orleans, he started painting professionally, portraying each bird with its realistic qualities.

Binoculars and cameras were not invented at the time, and birds do not stand still for someone to draw them. Previous artists shot the bird, skinned it, preserved it with arsenic, and set it up on a branch; the birds looked wooden and dead, and so did the artwork. Audubon changed the process, mounting his newly killed bird with wires on a board, positioning the bird in a natural position. He drew the bird, added watercolor, and used a cork to burnish the image and create the distinctive metallic look of the feathers. He generally worked out in the wilderness where he found the birds and, not wanting to waste anything, ate the birds after he finished painting the image and wrote about the taste of each bird in his books. He noted such information as; the raven is tough and not edible, or the teal is delicious, "probably the best of any of its tribe; and I would readily agree with any epicure in saying, that when it has fed on wild oats at Green Bay, or on soaked rice in the fields of Georgia and the Carolinas…it is much superior to the Canvass-back in tenderness, juiciness, and flavor."[3]

When he amassed a large body of work, he went on tour in England to great acclaim. He found a publisher, creating his best-known work, Birds of America, a book with over 400 drawings first published in 1827 and considered the finest ornithological work ever compiled.[4] Based on the popularity and success of the book, he created other well-known volumes of bird biographies. He is thought of as a forefather to the environmental and conservation movements of today. The Audubon Society was started in 1901. Its first action led to the establishment of the first National Wildlife Refuge on Pelican Island in 1903. The Society has been active in preserving wildlife for over a century.

Audubon was known for how quickly he drew. The turkey (4.7.7) was a large bird and easy to position. He sketched the essential parts before using watercolors to fill in the details. He was careful to add the proper background to each image; the mourning doves (4.7.8) are sitting in the same type of flowering tree they would in nature, while the woodpeckers (4.7.9) appear to be attacking the branch of a tree. Audubon always wanted each bird itself to be realistic and the setting and background based on the bird's natural environments.

When Audubon finished painting, he carefully dissected the bird and recorded very detailed information about each bird. When writing about the Roseate Spoonbill (4.7.10), he started with the exceptional bill the bird possessed, moving along the head and neck to the body. He wrote; "Legs long and rather slender; tibia bare in its lower half, and reticulate; tarsus rather long, stout, roundish, covered all round with reticulated subhexagonal scales…"[5], incorporating a complete description of the exterior and interior as well as measurements of each part of the bird.

Ledger Art (1860 – 1920)

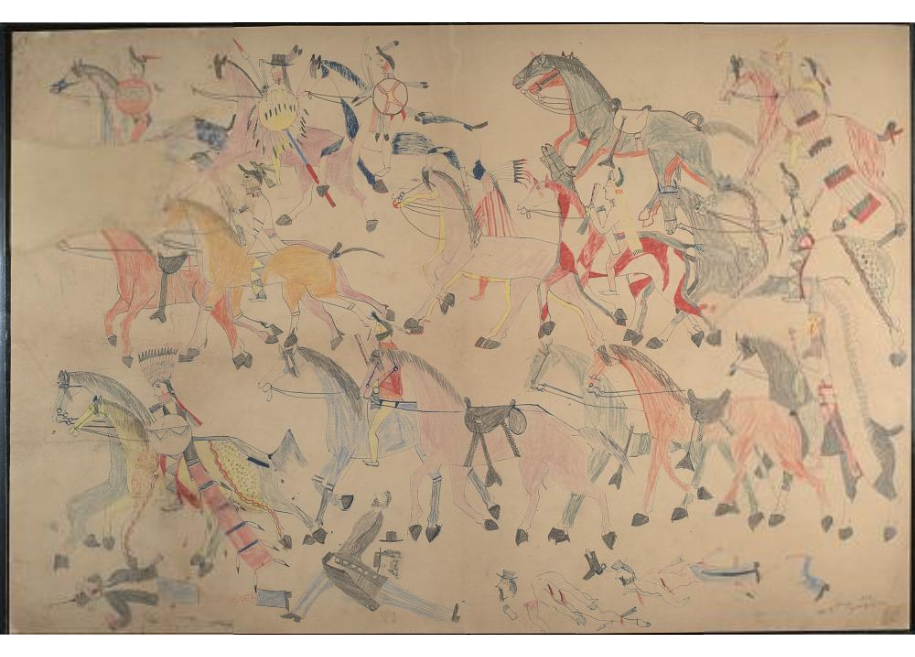

The Native American tribes living in the plains region of the United States have traditionally painted for a long time, men illustrating their individual feats of hunting, visions, or battles, women creating geometric or abstract designs. Their primary canvas was the hide of the bison, an animal almost totally eradicated by the U. S. government by the 1860s. As part of the paintings, on clothing, tipis, or other items, background color or design was unnecessary; the detail of the concept was the critical image. Usually drawn as an outline first, the design was filled with color. When the bison disappeared, the Plains artists turned to any available material, especially paper or fabric. As traders, the military, covered wagons, missionaries, or others passed through the region, they left ample supplies of ledger books with the paper used for recording information. The left-over books usually had supplies of ink, pencils, or paints, all acquired by trade or captured material.

With the new, smaller format of the sheet of ledger paper, a different art style was developed, accommodating the paper and new implements. Initially, military battles or raids were drawn; however, as the forced relocation of many tribes continued, the artists included scenes of life before the debilitating marches to reservations. Tribal and warrior history was always documented on an animal's skin. With the loss of bison skins, they transferred the information to ledger paper.

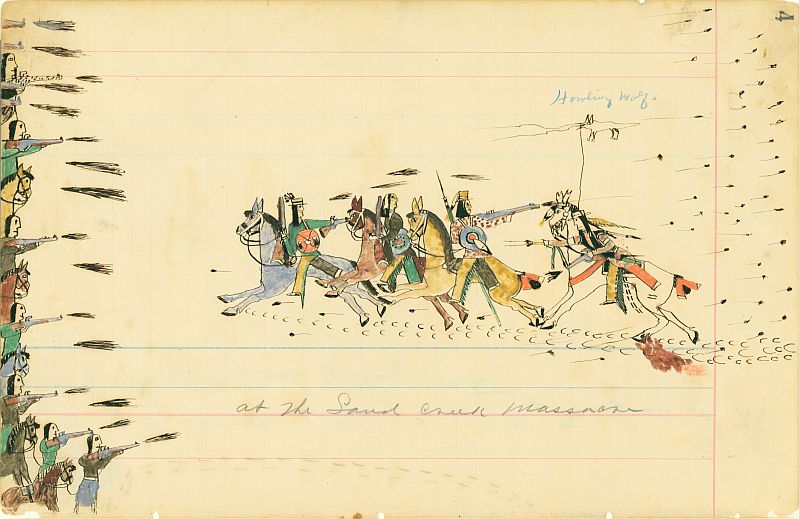

The narrative drawn on the paper resembles a freeze-frame of an event, an exploit happening in the battle at the time, the tribe's experiences, not stories about them. The information illustrated in the artwork had to be socially sanctioned by the participants, everyone agreeing to the event and details. The artist was generally not the warriors depicted, but the person most artistic and who could draw. A Kiowa ledger (4.7.11) probably depicts a battle at Buffalo Wallow in 1874 between the Kiowa and the U.S. Army. They were trapped in the natural depression, holding water the animals used for drinking and bathing. Each person was drawn with the accuracy of what they wore, their positions, those injured, and who actively engaged in shooting.

Howling Wolf

Howling Wolf (Ho-na-nist-to, 1849-1927) was a Cheyenne warrior who was also an artist, considered exceptionally talented; "he surpasses most other known pre-reservation drawings with respect to technical abilities, sense of design and innovative character."[6] At fifteen, he was one of the few men in camp on the reservation when the other men were out hunting. The U.S. Army attacked the camp without provocation, killing most of the women and children, mutilating the bodies, and taking the surviving men to prison, a shocking massacre. While in prison, Howling Wolf used ledger paper to draw, becoming a proficient artist and eventually selling his Ledger Art to tourists. In the image, At the Sand Creek Massacre (4.7.12), Howling Wolf is portrayed as the last figure shooing into the invaders as the other warriors are turned and firing at an unknown enemy. Bullets (looking like tadpoles) from the enemy flying through the air coming towards the riders. Each warrior was carefully portrayed in the clothing they wore and their equipment, even the proper treatment on the horses' tails. The hoof prints symbolized a lengthy pursuit.

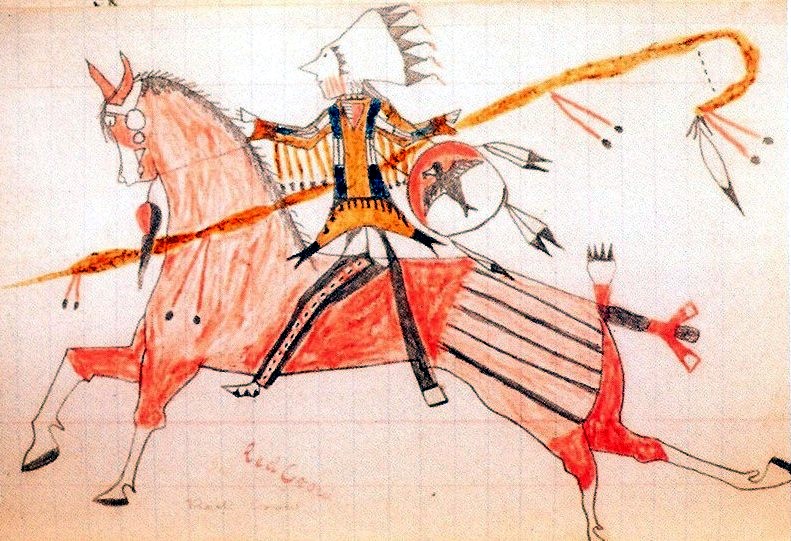

Red Dog

Red Dog (Shun-ka-Luta, dob unknown – c. 1882-1885) became a member of the Oglala tribe through marriage to one of Chief Red Cloud's sisters, becoming a frequent spokesman for the chief and a leader in his own right. Like the other Lakota and Dakota people, they witnessed the impact of the influx of non-Indians on their lands. Historically, the men had recorded their exploits in life and battle, first in ancient rock art, then for generations on bison skins until the U.S. government removed the bison. Around 1884, Red Dog became one of the significant artists recording the tribe's exploits and events. His drawings depicted warriors in complete Lakota regalia, ready for combat, and produced fifty-two drawings using crayons on paper.

"Drawings often show a favorite spear, bow and arrows, rifle, or handgun, or maybe just a rope or coup stick. A rope would find its way around a loose horse, and a coup stick was used to touch the enemy. It was more honorable to touch the enemy and get away with his possessions than to kill him. In Lakota values, being a warrior is an important aspect of bravery. Entering an enemy camp to take a prized horse or perhaps a herd of horses, often at high risk, was also a skillful act of bravery and chance. One eagle feather could be presented to a warrior for an outstanding deed. The riders in these drawings proudly display feathers they earned from previous encounters with the enemy."[7] Red Dog's crayon drawing of Low Dog (4.7.13) honors his abilities as a warrior, dressed in clothing, coup stick in hand.

Red Horse

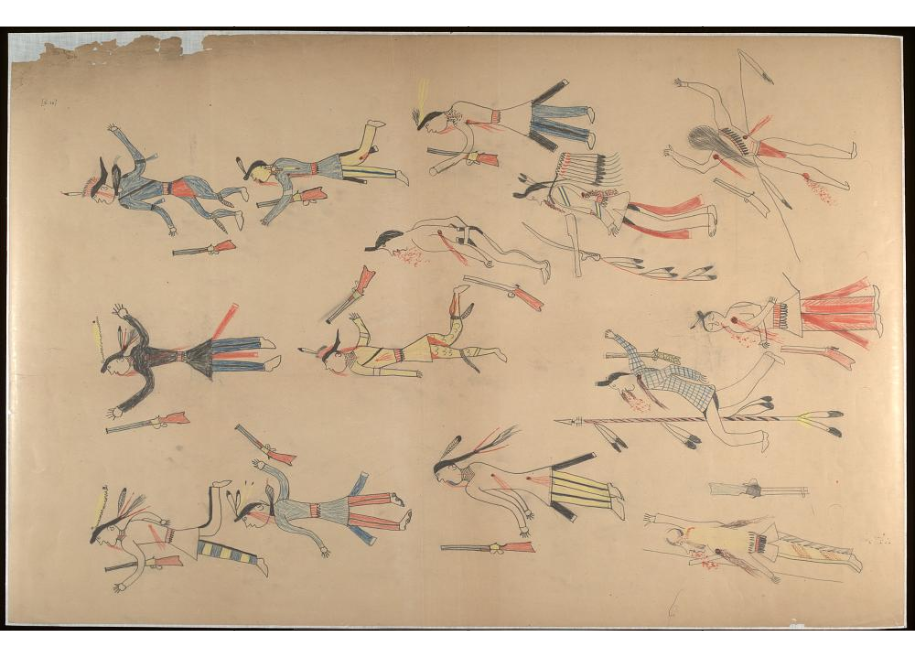

Red Horse (Tasunka Luta, 1822-1907) was a Sioux sub-chief who fought at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 between the U.S. army's 7th Cavalry and the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho combined warriors. The battle also called Custer's Last Stand, became a victory for the tribes, an overwhelming defeat for the cavalry. The army wanted to force the Lakota and Sioux back onto reservation land, and Custer was to make a stand at the Little Bighorn, a village site. Custer underestimated the size of the encampment, how many were waiting for the invasion, and the resulting massacre of his army. The battle has long been studied by historians and is the subject of movies and books.

In 1881, Red Horse, who fought at the battle, was commissioned by a doctor to create drawings about the event. Red Horse drew 42 different images about the warrior's experiences, including the invasion of the army on horses, scenes of combat, and imagery of the wounded and dead, all providing a different historical view of the experiences of the Battle at Little Big Horn. Historians view the drawings as one of the best and most trustworthy descriptions of the actual events of the battle from an authoritative warrior, not the sanitized and glorified narratives of Custer-centric versions. The Battle of the Little Big Horn (4.7.14) depicts the brutal battle in specific detail. Each person in (4.7.14) was lying on the ground, illustrated in their battle clothing, the cause of their death, and the place of the bullet's entrance in their body specifically noted with slashes of red. Image (4.7.15) displays how they were engaged in a close battle, saddles evident on the army horses, detailed buttons on their jackets, and the myriad of horse hooves all attesting to the incredible detail Red Horse included in his work.

The Western Artists

As the United States grew in the 1800s, artists traversed the countryside beside the explorers, surveyors, or settlers, documenting unknown spaces, wildlife, natural wonders, or the people inhabiting different regions, often glamorizing the scene while creating impactful views. The work of the artists documented the flora and fauna, history, and mythology.

Thomas Moran

Thomas Moran (1837-1926) was born in England and moved to Philadelphia as a child. He learned how to draw from his brother. Because he was talented as an illustrator, he was hired by a magazine to focus on painting landscapes in the west. Moran became interested in Yellowstone when he saw drawings from the surveyors of geysers and canyons. Moran joined a survey team exploring the region of Yellowstone, a territory unknown to the people of the eastern United States. Moran sketched and documented over thirty locations as he traveled through the area, noting the photographs and survey information. When he returned, he used the sketches to paint his first Yellowstone painting. His illustrations were used to motivate Congress, and Yellowstone was proclaimed the original American national park in 1872.

Moran returned multiple times to travel in the region and paint additional images of the majestic scenery he encountered. The scale and detail of his work brought the attention of the splendor of Yellowstone to the American people and the incredible beauty found in the western part of the United States, yet its vastness appears alien-like. His paintings brought the tourist industry to the region and the beginning of the destruction of natural resources. However, today, his work inspires the public to continue their efforts to preserve the wilder regions of America.

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (4.7.16) brings a primordial feeling, the expansive view with contrasting color, light, and shadows. The massive, thundering river creates a waterfall in the middle of the painting, seemingly diminutive in the broad landscape, yet demonstrating its power with the spray surrounding the river. Moran effectively used shafts of light to illuminate the multiple yellows and browns of the mountains. In the foreground, a small group of Native Americans stood, overlooking the scene, dwarfed by the enormity of the area. Moran's detailed rocks and bushes in the foreground demonstrate his ability to project realism into the background. It took him almost six years to finish the work the federal government purchased to hang in the Capitol.

The Grand Canyon of the Colorado River (4.7.17) is another of Moran's works to illustrate the immeasurable spaces in the American West. Rocky hills and mountains, clouds, water, and a hazy sky all form an almost apocalyptic impression, awe-inspiring and at the same time frightening. Moran paints highly detailed giant boulders in the foreground, every line and crack in the rock visible, and the background covers miles of fading mountains.

_-_Grand_Canyon_of_the_Colorado_River_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg?revision=1)

Mosquito Trail (4.7.18) is at the 12,000-foot elevation, a view of the Rockies in winter. A single rider walks his horse across the rocky terrain, each boulder magnificently detailed by Moran demonstrating the difficulty in crossing the terrain. He pulls the mountains up into the sky with the same white, gray, and blue colors—the height and steepness of the mountains visible as they sharply slant down to the distant valley floor.

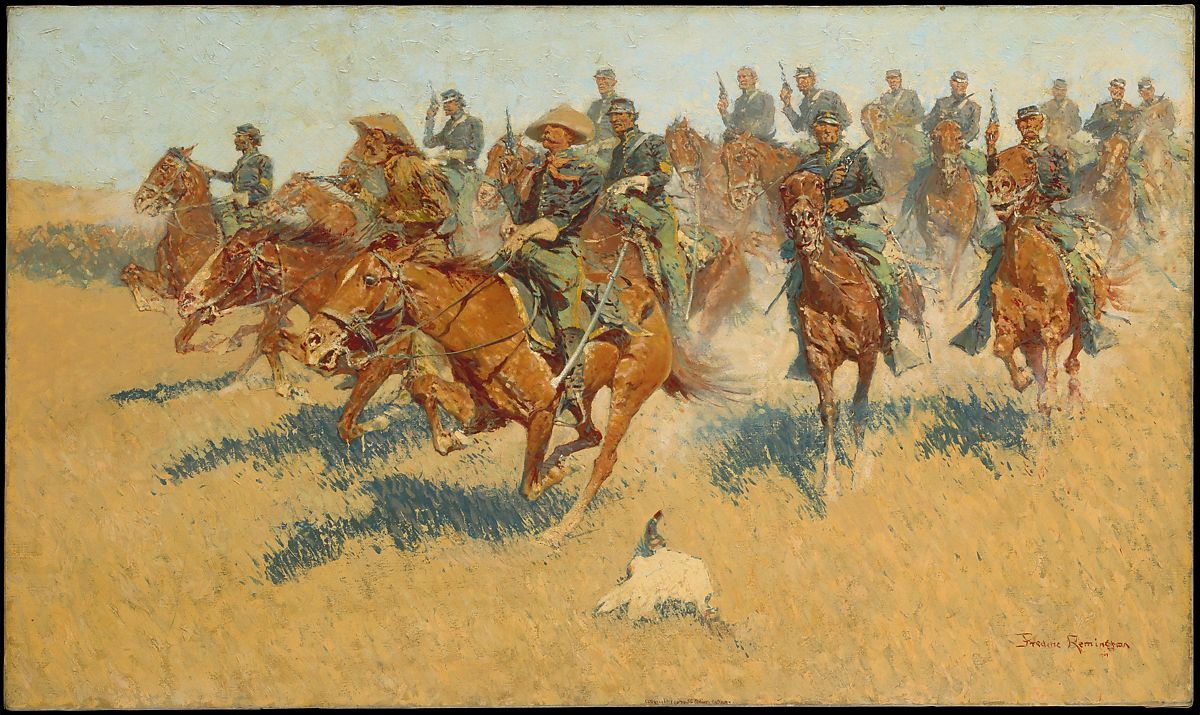

Fredrick Remington

Fredrick Remington (1861-1909) was born in New York and became part of the second-generation artists influenced by the Hudson River School style. Remington's father was an officer in the Union army. His ancestors fought in all the previous American wars, so he was familiar with the look of a soldier and his horse. He started in art school, only quitting to venture west and explore the prairies, encounter multiple Native American tribes, and view the disappearing bison, sketching as he journeyed. He tried owning a ranch and then a bar, unsuccessful adventures, so he turned to paint his perception of Western practices, a theme that brought him recognition and success, at first as an illustrator for magazines. He began to have one-person shows, and his adopted pseudo-cowboy persona and exaggerated western experiences added to his reputation.

Theodore Roosevelt said of him, "He is, of course, one of the most typical American artists we have ever had, and he has portrayed a most characteristic and yet vanishing type of American life. The soldier, the cowboy and rancher, the Indian, the horses and the cattle of the plains, will live in his pictures and bronzes, I verily believe, for all time."[8]

A Dash for the Timber (4.7.19) was characteristic of Remington's work, a painting commissioned by a prominent capitalist. The title suggests the eight frantic riders are heading for a grove of trees as protection against the pursuing Native Americans. The day's heat is evident in the dust, and lack of vegetation as small divots appear where a bullet missed its target and hit the ground. The action in the painting gives the viewer a sensation of hearing the noise of the guns, the clatter of horse hooves, the yelling of people, and all-powerful feelings implied in the painting. Although the cowboys seem to be the heroes, why were they being pursued? What happened? Remington loved the mythology of cowboys and the West. He portrayed them in great detail, as the Native Americans appear less defined, an indistinguishable mass, the perceived danger while the trees' safety is quite distinct. Remington's brushwork is fine and controlled using brushes with fine bristles, carefully defining each detail of the riders. The work helped perpetuate the myth and popularity of the cowboy.

On the Southern Plains (4.7.20) illustrates a favorite theme of Remington, the American soldier, believing them to be heroes. The soldiers, guns drawn, ride their horses at full gallop. The day's heat is evident in the dry dust the horses are kicking up and the shadows of the horses almost directly below them from the overhead sun in the cloudless sky. The riders are formed in a mass instead of the usual attack position of a horizontal line. He also positioned the weather-worn skull of a bison in the foreground, seemingly in the way. Remington made multiple visits to the Southwest, sketching the local landscape, and appreciating the quality of the unusual light.

The Bronco Buster (4.7.21) was Remington's first and most famous sculpture, the first image of a cowboy defined in bronze. The cowboy is portrayed breaking in the horse as the horse rears up and tries to unseat the rider, creating an iconic presentation of a romantic version of the cowboy. The statue was very popular and originally sand-cast, then lost wax cast, and later some bronzes were made from molds. This image of the statue, completed in 1918, was numbered 214 and was the last sculpture created.[9] Remington decided to study clay modeling and moved to sculptures, a very successful medium for him. He was known for the exceptional textural detail he used, building a story into the sculpture.

The Wounded Bunkie (4.7.22) portrays two soldiers retreating from an unknown enemy, a familiar image of those who patrolled along the country's frontier regions. One of the soldiers was injured with a bullet in his body. His bunkmate holds the trooper on his horse during the escape. The scene's intensity is evident; the horses raced at a fast pace, demonstrated by Remington with only two of the horse hooves on the ground, the other legs extended. Remington was a master at capturing the fear and quest for survival in the details of his statues, even in the limited size. His original models were destroyed in 1921; however, copies of his work are frequently constructed by others.

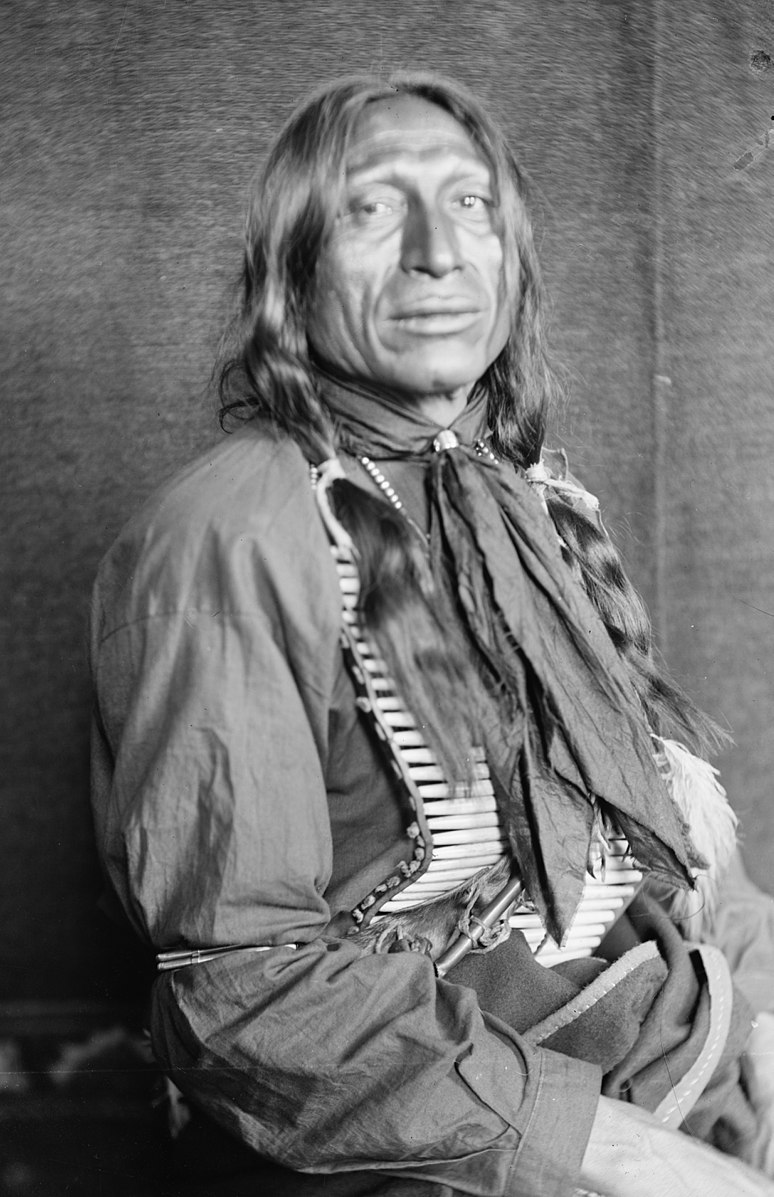

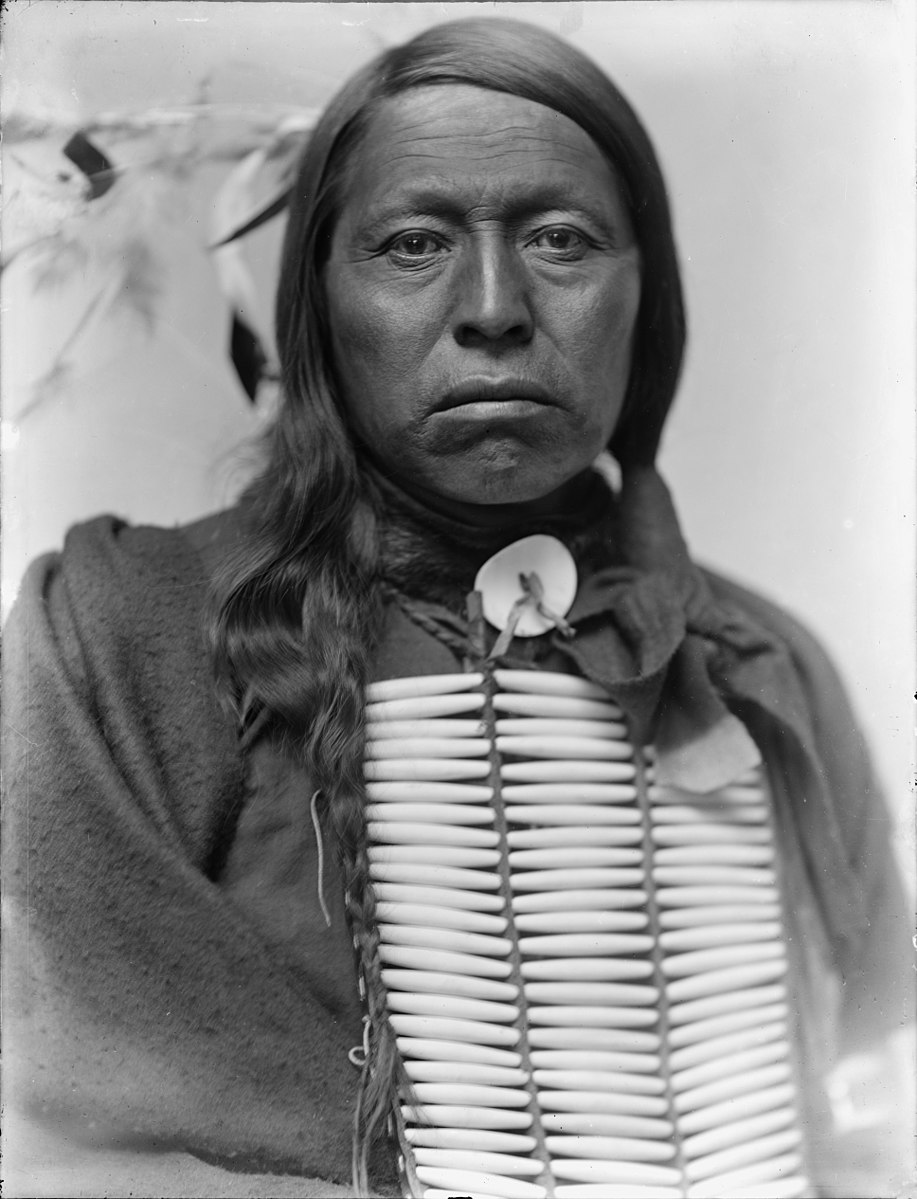

Gertrude Käsebier

Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934) was born in Iowa before moving to Colorado as a child, where her father became the first mayor of the city of Golden in the Colorado Territory. The family moved to New York and Pennsylvania during the Civil War. She married, had three children, and declared herself miserably unhappy; however, divorce was scandalous, so she remained married. At the advanced age of 37, she attended art school, even moving and studying at the Pratt Institute of Art and Design and traveling to Europe for additional education. Käsebier immersed herself in photography, unusual for a woman, a success for her. She approached photography differently; instead of a documentary approach to her subject matter, she accentuated the subjective view of a person or scene, a painterly methodology.

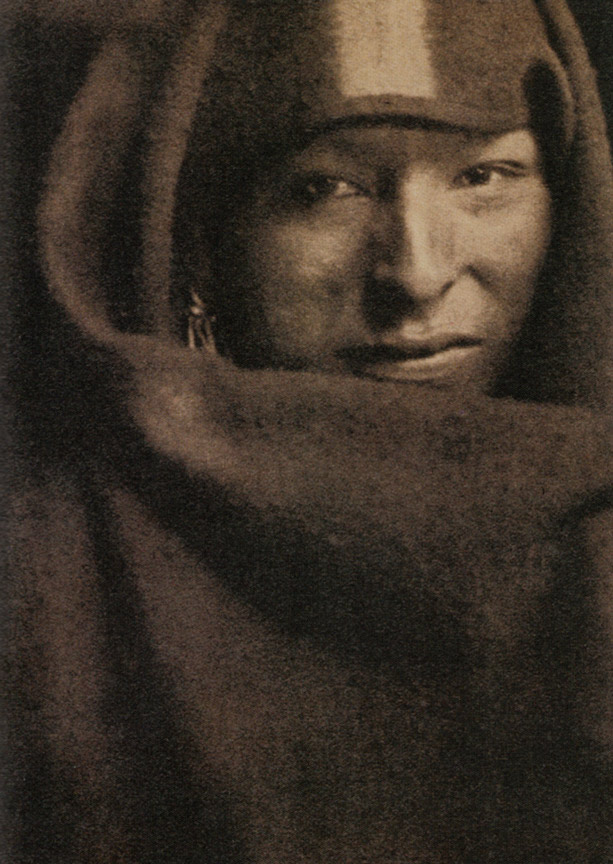

When William Cody Buffalo Bill's Wild West show was in New York, Käsebier remembered her time in Colorado and her connections with the Lakota living in the region. She asked William Cody if she could photograph the Sioux who were traveling with Cody as part of the show. Käsebier did not want to use the images for publicity; she wanted to photograph the men as they were behind the scenes, relaxed and intimate, without all the decoration worn at the show. She spent over a decade photographing men, women, and children, sometimes in formal attire and frequently informally.

Chief Iron Tail (4.7.23) was a veteran of multiple wars, including the Battle of the Little Big Horn, and was considered an elder chief. He traveled with William Cody and the Wild West show for almost twenty years, always leading the show's processions as Chief of the Indians. He agreed to pose for Käsebier, displaying his character; however, Chief Iron Tail did not like the print and tore it apart; Käsebier did a retake in his full regalia, keeping the incredible image of Iron Tail.

Chief Flying Hawk (4.7.24) was also a significant combatant in multiple battles, including the Battle of the Little Big Horn, the Great Sioux War of 1876, and the Wounded Knee Massacre. He was only with the show for a short time and frequently displayed his anger at the past injustices, a feeling seen on his face in the photograph. He did learn how to supplement his income with tourists at the show, charging a penny for postcards in full regalia.

Käsebier printed the negatives in platinum, a process in which the paper absorbs the emulsion, creating matte, textured surface. Artistic photographers favored platinum prints because they afforded a broad range of tonalities and hence less mechanical appearance. The pictures are not "black and white"' they include a spectrum of gold, brown, and warm gray shades. Käsebier and other pictorialist photographers asserted that their images should be considered art, a point that is well supported by the emotional quality and visual complexity of these prints.[10]

George Catlin

George Catlin (1796-1872) was born in Pennsylvania, inspired by his mother, who lived on the frontier and told him tales of Native Americans. Early in his life, Catlin worked as a lawyer and then an engraver, drawing images along the Erie Canal as a self-trained artist. He was inspired by relics from the early Lewis and Clark Expedition and a Native American delegation visiting Philadelphia. He decided he wanted to record information about the lives of the different tribes in America. In 1830 went with others up the Mississippi River into the regions inhabited by Native American tribes. The Indian Removal Act was just passed, starting the forced migration of southern native tribes to lands west of the Mississippi River, allowing white settlement on the ancestral lands. Catlin wanted to record the Native Americans before the frontier, and their way of life disappeared. Within a few years, smallpox decimated the tribes; bison plunged from millions to the remnants of a few thousand, and the prairies were covered with the railroad and over plowed land.

Catlin stated, "If my life be spared, nothing shall stop me from visiting every nation of Indians on the continent of North America."[11] He spent six years making five trips and encountering almost fifty tribes. He traveled up the Missouri River to the Dakotas and Montana two years later, meeting with eighteen tribes who inhabited areas untouched by European culture. He continued making journeys along the great rivers of the eastern half of the United States, collecting artifacts, sketching, writing, and painting over 500 images of the people and their environments. Catlin was the earliest major artist to traverse the country beyond the Mississippi, documenting native cultures before their irreversible alteration by the mass migrations and intrusion of settlers on their life. Although he worked with watercolor and oil paints, he also made numerous prints, preserving his work.

Travel through the regions was dangerous; the Native Americans aided in his safety, seeming to value Catlin's recordings of their tribal cultures. He painted the people in their full regalia, documenting the importance of their lifestyle in realistic portrayals and creating a historical and ethnographic record of the period. Catlin believed "his Indian Gallery was a national treasure, worthy of preservation by the United States government. Though he did not live to see his wish fulfilled, the original Indian Gallery came to the Smithsonian seven years after his death in 1872."[12]

Stu-mick-o-súcks, Buffalo Bull's Back Fat, Head Chief, Blood Tribe (4.7.26) was considered Catlin's best, an image of a significant chief portrayed in his magnificence. Catlin found most Native people living along the more settled frontier were haggard from diseases and poverty. However, Buffalo Bull's Back Fat (a prized part of the bison) lived in the northern plains, still free from settlers where he was a Blackfoot chief. Catlin recorded the chief as about fifty years old, good-looking and dignified. He wore a shirt of deerskin, the seams covered with a wide strip of embroidery made from porcupine quills, locks of hair from scalp trophies sewn along the edges of the embroidery.

Mew-hu-she-kaw, White Cloud, Head Chief of the Iowas (4.7.27), was one of the Iowa leaders Catlin painted. White Cloud is wearing a typical tribal headdress of a deer's tail dyed red and eagle quills. The Iowa usually painted elaborate designs on their faces; the green markings indicated his skill in combat. The necklace signified his rank as a chief, bear claws noting his exceptional ability as a hunter, beads, conch shells, and a larger shell in the middle. Catlin always included all the details of the chiefs' clothing to appropriately symbolize their rank in the tribe and their lifetime achievements. In 1832, when Catlin encountered the Iowa, White Cloud's father was chief; the tribe numbered about fourteen hundred people and had signed a peace treaty with the government, forcing them out of their homeland. When Catlin painted White Cloud in 1844, the Iowa were reduced to about 470 people.

Besides portraits of the chiefs, Catlin painted how they lived; scenes of bison, their homes, hunting, and games. He described the Crow Lodge of Twenty-five Buffalo Skins (4.7.28) as, "The Crows, of all the tribes in this region . . . make the most beautiful lodge . . . they oftentimes dress the skins of which they are composed almost as white as linen, and beautifully garnish them with porcupine quills, and paint and ornament them in such a variety of ways, as renders them exceedingly picturesque and agreeable to the eye. I have procured a very beautiful one of this description, highly-ornamented, fringed with scalp-locks, and sufficiently large for forty men to dine under. The poles which support it are about thirty in number, of pine, and all cut in the Rocky Mountains, having been some hundred years, perhaps, in use. This tent, when erected, is about twenty-five feet high, and has a very pleasing effect."[13]

Catlin painted images of women and children as well as men. Tis-se-woo-na-tis, She Who Bathes Her Knees, Wife of the Chief (4.7.29) was painted at Fort Pierre. She was the wife of the Cheyenne chief, Wolf on the Hill. As part of Catlin's documentation to ensure his work was acknowledged correctly, he frequently had agents at the fort write authentication papers, noting Catlin as the artist and the image's name, place, and tribe. Catlin wrote of Bathes Her Knees as "comely, and beautifully dressed; her dress of the mountain-sheep skins, tastefully ornamented with quills and beads, and her hair plaited in large braids, that hung down on her breast."[14] She is wearing a dress made from mountain sheep skins embellished with porcupine quills and beads patterned into geometric designs used by the Cheyenne.

The United States changed significantly in the 1800s from the beginning of a developing country. The Louisiana Purchase doubled the nation's size, starting a massive expansion westward, moving populations from east coast states into the wild west, displacing and decimating the Native American tribes and forcing them onto reservations. This was the industrial age; crops were grown on large plantations, railroads across the country, the discovery of mineral wealth, manufacturing, mechanization, exploited labor, a civil war, and the government's growth. Through it all, new states were added, gold was discovered, natural parks were formed, slavery was abolished, and art in the United States flourished.

Both Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran created paintings of the unique western landscape. These paintings inspired and educated people and the government, helping establish the national park system and reserving the wilderness today. They traveled the western regions, making sketches and painting the power of waterfalls or mountain peaks.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.history.com/topics/us-government/national-park-service

[2] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10497?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=thomas+cole&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=2

[3] Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/john-james-audubon-americas-rare-bird-97819781/

[4] Retrieved from https://human.libretexts.org/Courses/ASCCC/A_World_Perspective_of_Art_Appreciation_(Gustlin_and_Gustlin)/10%3A_The_New_World_Grows_(1700_CE_%E2%80%93_1800_CE)/10.06%3A_Natural_History_Illustration_(18th_Century)

[5] Retrieved from https://www.audubon.org/birds-of-america/roseate-spoonbill

[6] Szabo, J. (1984). Howling Wolf: A Plains Artist in Transition. Art Journal, 44(4), 367-373. doi:10.2307/776774

[7] Retrieved from https://americanindian.si.edu/exhibitions/infinityofnations/plains-plateau/206230.html

[8] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/remi/hd_remi.htm

[9] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11860

[10] Hutchinson, E. (2002). When the "Sioux Chief's Party Calls": Käsebier's Indian Portraits and the Gendering of the Artist's Studio. American Art, 16(2), 41-65. Retrieved June 2, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/31093

[11] Brian W. Dippie, et al George Catlin and His Indian Gallery (Washington, D.C., New York, and London: Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with W.W. Norton & Company, 2002)

[12] Brian W. Dippie, et al George Catlin and His Indian Gallery (Washington, D.C., New York, and London: Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with W.W. Norton & Company, 2002)

[13] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/crow-lodge-twenty-five-buffalo-skins-4019 (Catlin, Letters and Notes, vol. 1, no. 7, 1841; reprint 1973)

[14] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/tis-se-woo-na-tis-she-who-bathes-her-knees-wife-chief-4362 (Catlin, Letters and Notes, vol. 2, no. 32, 1841; reprint 1973)