4.5: Yoga and Nihonga (1870-early 1900s)

- Page ID

- 120751

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Paintings in Japan are categorized into Yōga and Nihonga; the categorization permeated every aspect of painting in Japan. Each category had its artists, exhibitions, competitions, judges, institutions, and educational curricula. Yōga meant "Western-style painting," aligning with the Western (European) artistic convention in concepts, materials, and techniques. One of the foundational concepts of Western painting is the life-like depiction of the world on a flat surface. Nihonga meant "Japanese-style painting" in the traditional Japanese counterpart of Yōga. For example, Yōga artists used oil on canvas, and Nihonga artists used sumi ink and water-based paint on washi-paper or silk. Established during the era of modernization in nineteenth-century Japan, these two categories contrasted and defined each other. In the world of modern Japanese painting, neither existed without the other.

The opening of Japan in 1854, the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1867, and the Meiji Restoration in 1868 intensified the dialogue between Japan and the West. Japan was anxious about foreign imperialism. Meiji officials understood Japan's independence was only safeguarded through rapid modernization in technology and industry.[1] Japan needed to be more like the Western world to prevent colonization. In the early Meiji period (the last half of the nineteenth century), Japan was modernizing rapidly in its aspiration to become more like the West. The art world was fueled with the same energy; within this historical context that Yōga and Nihonga were born.

Yōga

Yōga represented Japan's more diverse artistic part, gravitating towards the West. In Yōga, Japanese artists painted or drew in Western-style. They used techniques and materials found in European art such as oil paint on canvas, ink, pastels, and watercolor. The goal was to create a Renaissance-based, realistic picture on a flat 2-dimensional surface. They perfected the skills of linear and atmospheric perspectives, shading, and color-mixing to mimic the natural world. European or American instructors were invited to Japan to teach, and some Japanese artists went to study in France. As art students in the second half of the nineteenth century, Japanese artists encountered Academism, Realism, and Impressionism and trained in those styles. After their training, they brought the concepts back to Japan, and the styles influenced the establishment of Yōga.

The tendency toward image-making in Western-style was not a sudden event that started as Japan opened to the world in 1854. Even when Japan was still a closed country in the eighteenth century, some artists were already studying a Western mode of pictorial representations such as linear perspective. Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), including Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), demonstrate the concept. The fame of the Great Wave off Kanagawa print and Nihonbashi in Edo (4.5.1) from the series 36 Views of Mt. Fuji demonstrate Hokusai's knowledge of linear perspective. In the Nihonbashi print, the rows of houses flanking the river recede uniformly and accurately, taking the viewer's eyes towards the vanishing point at the Nihonbashi bridge.

At the beginning of the Meiji era (1868 – 1912), the government was very anxious to emulate the West in every aspect of Japanese society and culture. Art academies and technical schools were established to facilitate the goal. Technical Fine Art School (Kobu Bijutsu Gakkō) in 1876 was the first government school to teach Western art and design techniques to Japanese students.[2] Three Italian instructors were hired, including Antonio Fontanesi, responsible for painting and drawing. Although he was only in Japan for two years (1876-1878), Fontanesi introduced the next generation of Japanese artists to Western media such as charcoal, pastels, and oil paint. Fontanesi taught the foundation of 2-dimensional arts, including anatomical studies, linear and atmospheric perspectives, painting and sketching from live models, and en-plain air painting.

In the 1880s, there was a backlash against the intense westernizing energy of the early Meiji period, and the pendulum swung towards the appreciation of Japanese traditions in art. Nihonga, or Japanese-style painting, resulted from the revival. Yōga fell out of favor, and the 7-year-old Technical Fine Art School closed in 1883. These events demonstrate the duality in Japanese painting, a fluctuation between Japanese tradition and Westernization in search of its modern identity.

Considered the father of Yoga, Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924) was the most successful and influential advocate of this painting category. It was primarily under Kuroda's leadership that Yōga moved toward a viable position in modem Japanese art in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Returning from Paris in 1893, Kuroda took a leading role in revitalizing Yōga, which was out of favor in the 1880s. Kuroda brought back with him a style based on Plein-air Impressionism. Kuroda's paintings were generally well-received by the Japanese audience. His accomplishment served as an inspiration and point of departure for many influential Yōga artists of his generation and beyond. More than a transplantation of foreign formal elements, the establishment of Kuroda's approach signaled the liberation of artistic freedom for Yōga artists who were working in an oppressive academic manner. Kuroda was successful in bringing Yoga to a broader Japanese public because he infused Japanese elements into the surface depth of perceived Western-style oil paintings. Kuroda's pictorial representation, his choice of subject matter, and his call for artistic freedom (in the face of strict academic naturalism) contain aspects reverberating with Japanese aesthetics.

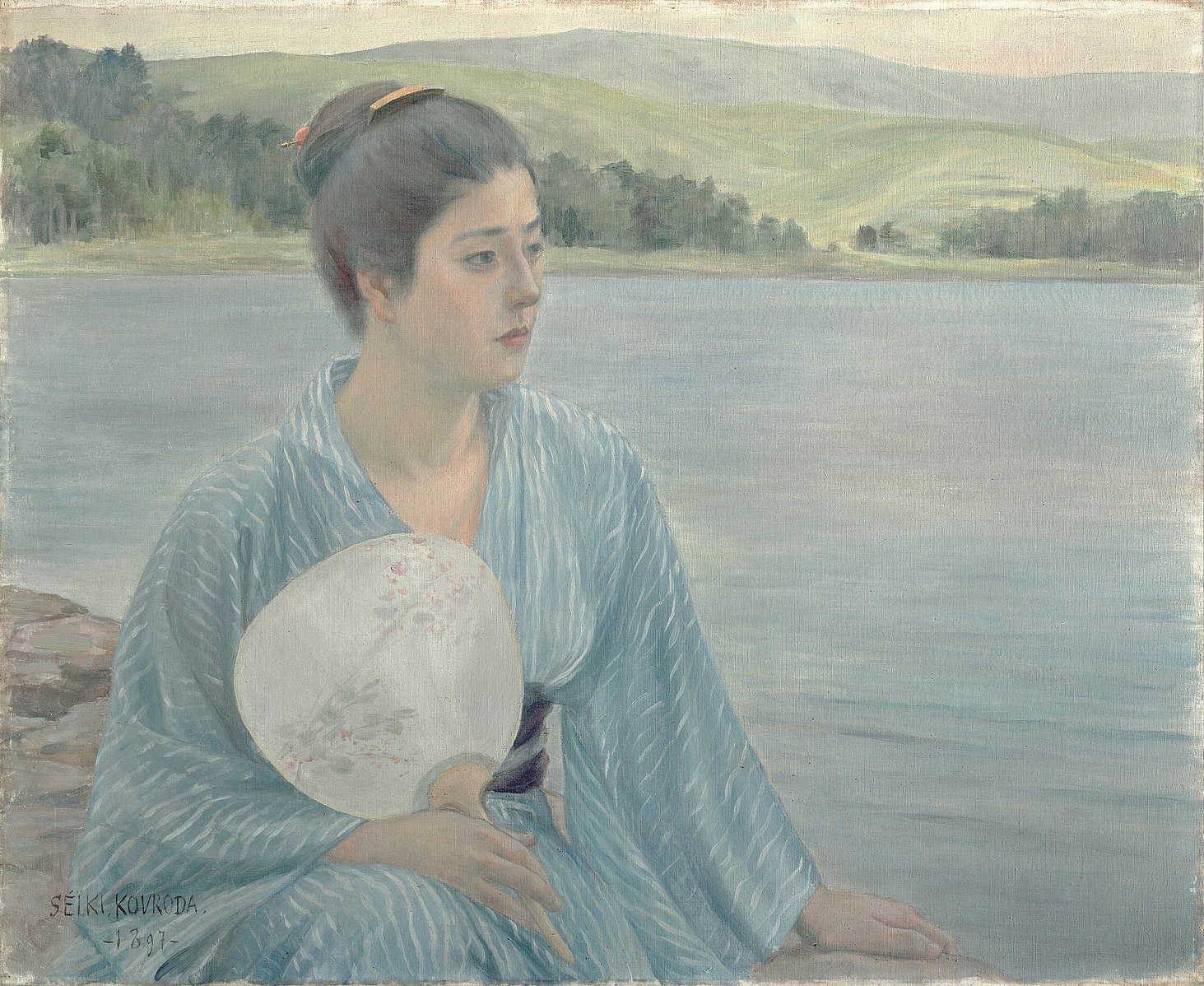

Lakeside (4.5.2) is probably one of the most famous Japanese paintings based on Western-style. At a glance, there is nothing extraordinarily spectacular about the painting. It was a far cry from Kuroda's more experimental pieces like Morning Toilette. The subject matter of a standing nude generated controversy and made Kuroda the center of attention at the Fourth National Industrial Exposition in Kyoto. In contrast to Morning Toilette, the subject matter of Lakeside is rather conservative: a traditional beauty in her light summer kimono (yukata), contemplating nature as she sits by the lake. The painting is rather soothing in its tranquility; the harmonious blue tonality complements the complexion of her skin and the white fan that she holds against her breast. Kuroda used the methods of filling the canvas without any negative space. Despite using oil paint and visible brushstrokes, the painting conveys a feeling, theme, and mood completely Japanese and why Lakeside enjoys its success in the history of Japanese modern art.

Kuroda's choice of subject matter – a woman in a traditional outfit -- resonates with the Japanese tradition of Bijin-ga. The term means "image of beautiful women;" it is a subject that recurs throughout Japanese art history. "Bijin" refers to traditionally clothed and adorned beauties. The immediate origin of modem Bijin-ga is found in genre painting popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the Edo/Tokugawa period (1603-1867), the lineage of bijin-ga was maintained primarily by ukiyo-e artists such as Torii Kiyonaga and Kitagawa Utamaro. The favorite subjects were courtesans from the pleasure quarters or local beauties in various activities. There is a parallel between Torii Kiyonaga's print Enjoying the Evening Cool on the Banks of the Sumida River (4.5.3) and Lakeside. They both offer candid images of ladies captured unaware as they enjoy the natural beauty of their environment and the cooling breeze in the heat of summer. The woman in the middle of Torii Kiyonaga's print is similarly silhouetted against the landscape like Kuroda's subject.

Since Bijin-ga is a revival of archaic and native subject matter, it is typically not expected to be found in Yōga as the modern and westernized vehicle of expression. Although it may seem ironic, the most critically acclaimed Yōga masterpiece – Kuroda's Lakeside – is essentially a Bijin-ga cloaked in the medium of oil in a naturalistic western-style rendering. It is perhaps more instructive to see its success was due to its ability to synthesize traditional Japanese and Western visual idioms in one artwork.

Asai Chū

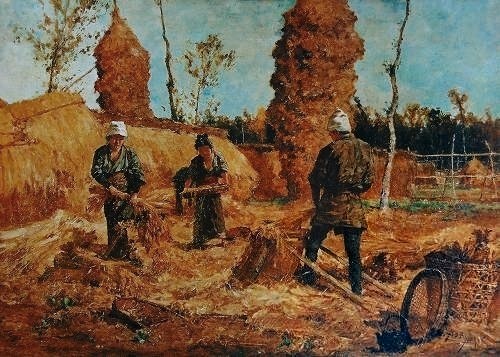

Yōga was expected to depict the representation reality of the time. Asai Chū (1856-1907) was born in Tokyo, drawing as a child. He attended art school to where he learned about Western-style painting. Later, he established a group of artists who wanted to paint in the new methods and became a professor in art school, teaching many of Japan's well-known artists how to bridge traditional techniques and the more contemporary methodologies. As an artist, Asai usually used humans performing some sort of farming or other rural style work in his paintings. Harvest (4.5.4) depicts the ordinary farmer working the land. Browns and greens composed the primary color palette with loose brushstrokes visible in the ground. The painting portrays the gritty life of Japanese farmers in the tradition of the French Barbizon School.

Nihonga

The enthusiasm for everything Western was strong in the early Meiji and lifted the brief excitement for Yoga. However, a movement to return to native values in art was gaining ground in the early 1880s. The craze for everything Japanese in Western Europe and America (Japonisme) and the popularity of Japanese traditional arts and crafts in international expositions led to the evaluation of Japanese traditional arts and the desire to revive them. In 1878, the Vice-Minister of Education, Kuki Ryuichi, was sent to observe the developments in education and art at the Paris Exposition. He also attended the Provincial Congress of Orientalists held in Lyons in France. He was impressed by the depth of knowledge and interest in Japanese art and culture and the importance the French attached to artistic achievement and their cultural heritage. Returning from Paris, Kuki was convinced that promoting Western-style painting was foolish when Japan possessed a unique artistic tradition as a source of national pride and international prestige. In 1879, Kuki helped establish Ryuchikai (Dragon Pond Society) to capitalize on the foreign interest in Japanese art. He hoped to stimulate greater interest among the Japanese in their artistic heritage and modem revival of traditional Japanese arts and crafts. Nihonga was the result of this revival.

Nihonga was used to define a Japanese visual style against other foreign-based approaches, especially Yōga (Western) and Bunjinga/Nanga (Chinese). Its main characteristics are reminiscent of the Yamato-e (Japanese) decorative tradition: well-delineated flat areas of translucent or opaque, bright color plates; the avoidance of rendering form in a realistic treatment of light and shade; and the use of negative space. The effect achieved also incorporated the traditional materials used of paper or silk for the surface, Sumi ink, and mineral and vegetable pigments in a binding agent. Pigments were not mixed to form a wide range of shades as in Western oil painting. Consequently, the clarity of colors was preserved, a distinguishing feature of Nihonga even when the effects of light and shadow were attempted by the later generation of artists. The subject matters of Nihonga revolved around Japanese mythological and historical themes, native landscapes, and Buddhist iconography.

Kanō Hōgai

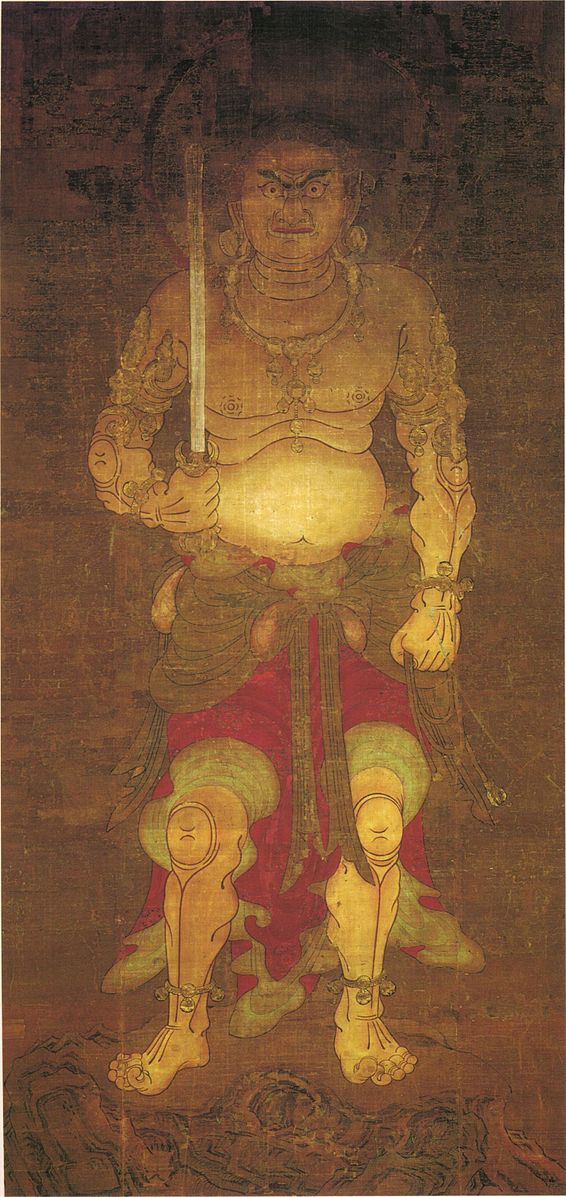

The comparison between Fudō Myōō (4.5.5) by Nihonga artist Kanō Hōgai (1828-1888) and a painting with a similar subject matter from the 12th century (4.5.6) demonstrates how Nihonga reinvents and refresh traditional Japanese idiom in the nineteenth century. As a protector of Buddhist law, Fudō Myōō is a widely represented guardian figure in the Buddhist Pantheon. The iconography of Fudō Myōō typically includes a muscular figure with a fierce expression equipped with a sword and a lasso. Both paintings contain the same iconography; Kano has stylized the musculature of his figure to approximate the medieval version. The difference is that the nineteenth-century Nihonga painting demonstrated an awareness of two things: modeling three-dimensional shapes with shading and the perception of depth. The Nihonga Fudō Myōō is placed at a three-quarter view, immediately giving the painting a depth the frontal 12th-century image does not have. He sat on a rock between clearly delineated rocks in the foreground and subtle hints of rock formation beyond it. The "layers" of foreground, midground, and background create the idea of depth inside the picture plane the way Renaissance painting did. Although the figure is clearly outlined, there are subtle highlights and shadows in the face, arms, torso, calf, and red drapery, creating a missing volume in the 12th century Fudō Myōō figure. The illusion of depth and sense of volume are two features typically found in naturalistic Western painting. Kanō Hōgai used the subtlety of the techniques, only apparent with deeper analysis. To counteract these Western characteristics, the background and the area surrounding the main figure are empty. This void relates to negative space, the signature characteristic of Japanese paintings. Nihonga is a hybrid invention of modern time, a synthesis of Western and traditional Japanese visual elements.

.jpg?revision=1)

Hishida Shunsō

Fallen Leaves (4.5.7), a quiet, lyrical painting by Hishida Shunsō (1874-1911), demonstrated the relationship between naturalism, an illusion of depth, and the use of negative space in Nihonga. Another element of the Japanese tradition of the painting is its format; the images were painted on a pair of 6-panel free-standing folding screens. Known as "byōbu," the screen functioned as a movable room partition while the painting acted as an interior decoration for the room. It was a popular furniture item in the home of high-ranking samurais. The screen featured a pine sapling with green leaves. Across the horizontal surface, Hishida painted leaves, tree trunks, and birds, creating an asymmetrical composition with the negative space on the right contrasted with the area filled with tree trunks on the left. The tree trunks in the foreground were painted with meticulous naturalism, a detailed rendering of the bark and leaves, demonstrating Hishida's observation of the world around him. The detailed textures of the tree trunks gradually lessen as the trees become smaller, indicating the illusion of depth. The background on the right side of the image is mainly empty, balancing the relative fullness of distant trees to the left. The empty space is indeterminate as Hishida simply left it unpainted, leaving the viewers' imagination to complete the image. The use of negative space balanced the space filled with tree trunks to indicate depth. In the foreground, a green sapling anchors the painting as its focal point, its green leaves standing out against the surrounding beige, brown, and orange colors. Two tiny birds peer among the fallen leaves, completing the composition. Hishida synthesized and balanced Japanese and Western painting styles; nature lived harmoniously in the painting.

Yokoyama Taikan

The difference between Nihonga and Yoga painting styles is reflected in the two paintings, Towing a Boat (4.5.8) by Yokoyama Taikan (1868-1958) and Withered Field (4.5.9) by Kuroda Seiki. In Towing a Boat, the water and rocks are painted in the Nihonga style using the more obscure method, the colors defining the shapes are flattened, and the wood and stones do not have the typical outlines of Nihonga. However, the image is traditional, the power of nature apparent and the smooth flat brushstrokes help create empty space. The water flows down the mountain into the river in typical Japanese style. The negative space is consumed by fog, which expresses the moisture in the air while creating the usual negative space. Yokoyama was ridiculed; however, his changes helped modernize Japanese paintings. The Withered Field followed Plein aire techniques, painted outside, every part of the canvas filled with bold and broad brushstrokes and color to create the illusion of grasses. Kuroda filled the space in typical Yōga style. The sky covered the canvas from side to side, dark and ominous as the storm approached. The mountains bisect the canvas, a field of grasses formed from broad brushstrokes and mixed colors follow the Impressionist style, which influenced Yōga techniques.

.jpg?revision=1)

[1] Vos, F., "Waken Yosai - Japanese Spirit and Western Achievements" in Schaap, R (ed.), Meiji:

Japanese Art in Transition, Leiden: Haags Gemeentemuseum, 1987, 15-16.

[2] Yoshinori Amagai, “The Kobu Bijutsu Gakko and the Beginning of Design Education in Modern Japan,” Design Issues 19(2), MIT Press, 35.