4.4: Post-Impressionism (1886-1905)

- Page ID

- 120750

Introduction

Post-Impressionism started as an extension of the use of color and light by the Impressionists, soon pushing past the limitations of the style into new expressions and moving from the short, broken brushstrokes to forms filled with bright colors. Many artists started with Impressionism's standards, changing to new styles and generally painting in isolation. During the Post-Impressionist period, different and experimental short-lived designs started; Les Nabis, Neo-Impressionism, Pointillism, Symbolism, or Cloisonnism. Although the artists did not classify themselves in any group, a local art critic called them Post-Impressionist after viewing a show in London, a term staying as an art movement.

The Post-Impressionists painted real-life, frequently slightly distorted using very bright colors applied with thick layers of paint. Sometimes the color was unnatural, selected by the artist, not real life, and bordering on the abstract. Artists tried different techniques; Seurat used color applied with tiny dots, Cezanne painted simple shapes, while Van Gogh swirled paint on his brushes across the canvas. The artists wanted to express feelings, their subconscious, and emotion. Gauguin believed color was the language of his dreams, while Cezanne thought art was not art without emotion.

The Impressionists used natural light to define their paint colors; the Post-Impressionists used saturated hues and artificial colors for their palette. Both styles used brushstrokes, short or broad, very visible; however, the Post-Impressionists were not trying to form the brushstrokes into a realistic image, merely a representation.

Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), born in France, established the movement's beginnings from pure Impressionism to Post-Impressionism. Picasso referred to Cézanne as "the father of us all," and Matisse called him "the master of us all" as Cézanne opened new ideas to artwork.[1] He moved from the brushstrokes of the Impressionists to brushstrokes using color to build complex areas on the painting. Early, his participation with the Impressionists was minimal, entering only two of their shows, received poor marks from the critics, and had little success selling his work. Fortunately, he was from a wealthy family and did not need to be a commercial success as he continued to create his style.

It wasn't until later in his life, that he became accepted and promoted by other artists and finally had a solo show in the early 1890s. The exhibition displayed almost 150 works Cézanne had painted and stored away or given to others, an exhibition showing the wide range of Cézanne's art and his immense talent, garnering wide admiration. Exploring outdoors with his friend Pissarro and other artists, his early work focused on landscapes and figures in the landscape created by layering paint in thick layers in darker hues. As he moved away from the style of the Impressionists and developed his own, he wanted the beauty of the work to become the focal point instead of how it was rendered, not perfectly posed. He focused on selected ideas; still life, landscapes, and portraits of people he knew well. One characteristic he used in most paintings was painting short parallel lines that slanted obliquely, a type of texture other artists adopted. "His unique method of building form with color and his analytical approach to nature influenced the art of Cubists, Fauves and successive generations of avant-garde artists."[2]

The Large Bathers (4.4.1) was considered one of his early break-away paintings, moving from tradition into Post-Impressionism. The painting appears to be en plein aire, an outdoor scene with a bright blue cloud-filled sky. However, Cézanne did not use real models and painted the image from his imagination and memory of days spent outdoors. The lush, colorful background appears as the stage, the tree trunks bending to form the scene, the bathers positioned across the shoreline, engaged in different activities, seemingly incompletely painted. After 1880, Cézanne lived in Aix, his family home, where he did numerous local landscape paintings. He developed a series of horizontal layers to build dimension and depth into the work.

Mont Sainte-Victoire and the Viaduct of the Arc River Valley (4.4.2) depict the mountain dominating the local landscape. Using muted colors, a set of bushes runs horizontally across the bottom of the painting, then the valley with the bridge moving, the mountainous layer, and finally the sky, each building the horizontal distance. He used the vertical foreground trees to give the final depth and feel of distance to the painting, feeling the geometry found in nature.

In the mid-1870s, Cézanne changed his methods, experimenting with different color tones and how brushstrokes changed dimensions. He began to paint carefully constructed still life using subtle changes of color without a strong light source to create slightly distorted scenes. Each image in the painting held it to the total image, an apple might be oversized or appear to be falling off the table. The painting Jug Curtain and Fruit Bowl (4.4.3) is one of Cézanne's most famous still life images. The white tablecloth provides the fundamental contrast to hold the images laying on a tabletop, each side of the table a different size and thickness. Each piece of fruit contrasts with another; the rich dark greens, reds, and yellows bring energy as the eye moves around the painting. The apples stacked in the bowl have a flat look as they all sit evenly, while some of the fruit looks like it will roll off the table.

Cézanne became known for the technique of disjointed perspectives; in The Basket of Apples (4.4.4), the table dimensions differ on each side. The bottle slanted towards the tilted basket, all realistic as a total image. Sitting on the classic white cloth, he used the repetition of the green, yellow and red fruit, each entity bringing balance into the painting, applying heavy brushstrokes to bring each piece of fruit to life.

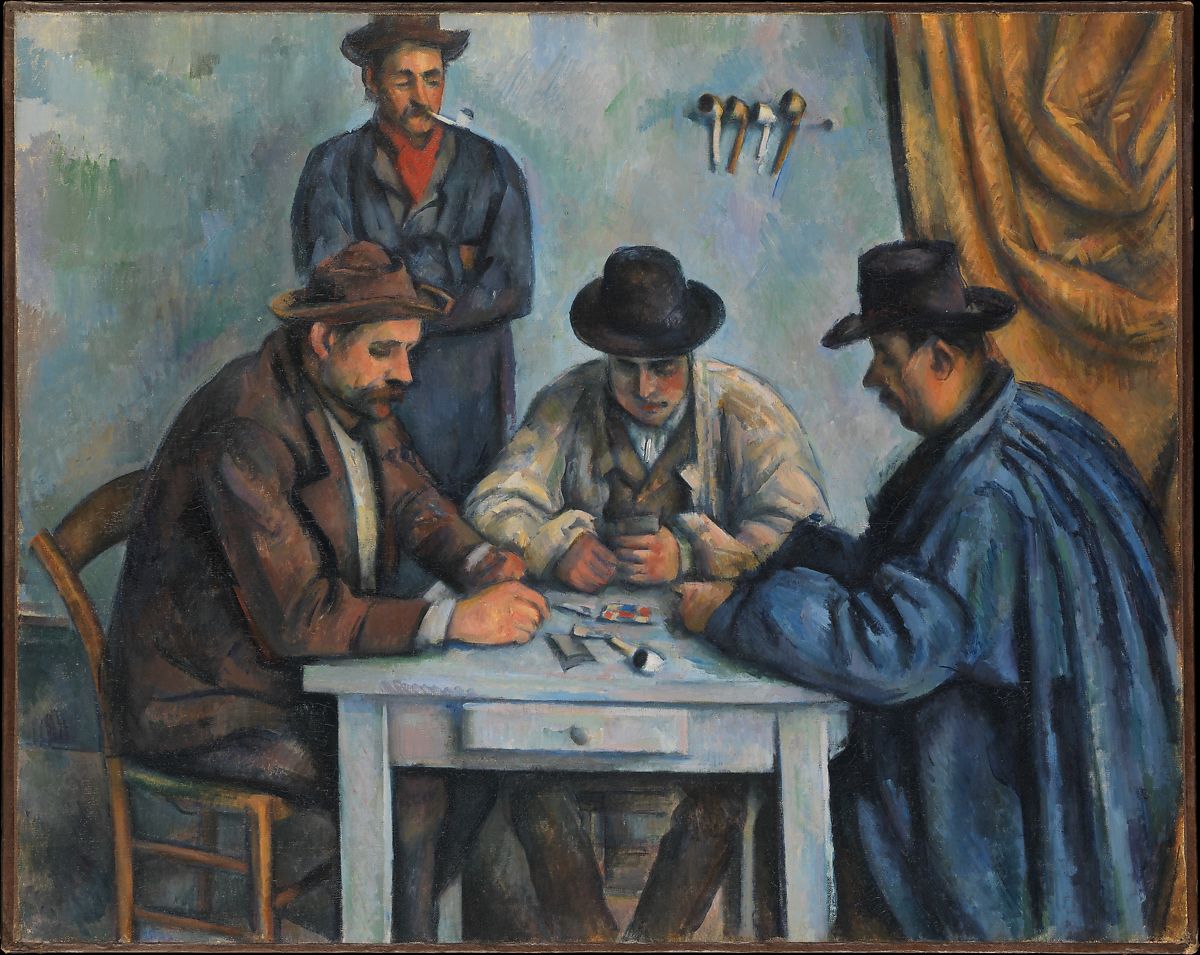

Cézanne painted multiple images of local people doing ordinary things, including five paintings about peasants and their card games. In The Card Players (4.4.5), the soft blue background and table help instill a feeling of quietness and patience in their card game; the men are looking down at their cards, deep in concentration. Pipe smoking was a standard part of their lives, and pipes appear hanging on the wall, on the table, and in the mouth of the bystander. Many believe the card player paintings followed Cézanne's love of still life, depicting an artfully arranged human still life.

Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat (1859-1891), was born in Parisa and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts where he was educated on color theory and chromatics, especially those ideas written by Chevreul. When the Salon rejected him, he and other artists opened the Salon des Independants, based on their concepts of Divisionism or Pointillism as it is known today. Seurat placed small dabs of colors next to each other to mix in the viewer's eye, forming the image he wanted to present and controlling the colors. He died at a relatively young age, and his parents tried to donate his paintings to the Louvre; however, they refused, and his work was dispersed among friends.

Seurat studied color and the effects of adjacent colors on each other; a red color placed beside blue looks different than if the red is placed by green or even red alone. Seurat knew how to raise or lower the tones of color based on their juxtaposition to another color, a technique he used in his paintings. In Young Woman Powdering Herself (4.4.6), the blue background color is intensified, enhancing the pale colors on her arms and the lace of her straps. He used different tones of blues to develop the shadows on the wall. The table's legs are bowed outward so she can sit; however, the tabletop is very small, and the mirror perched carefully on top.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_95.5_x_79.5_cm%252C_Courtauld_Institute_of_Art.jpg?revision=1)

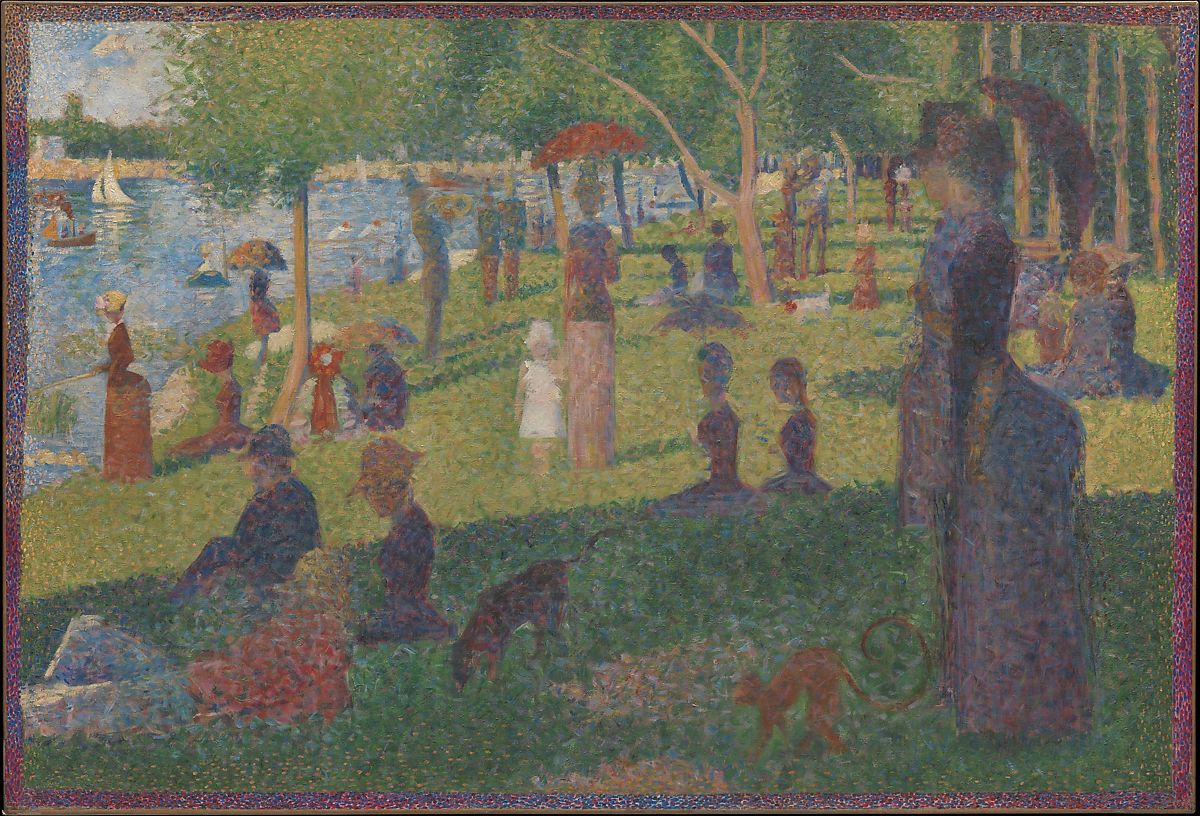

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (4.4.7) brought cries of "Bedlam, scandal, and hilarity was among the epithets used to describe what is now considered Georges Seurat's greatest work…"[3] Seurat created his masterpiece by juxtaposing tiny spots of color based on the interaction of tones with each other. The figures feel forever immobilized in time; their deep shadows froze in place, a seeming silence covering the scene. The island was in the Seine with a grassy, steep bank. Seurat returned multiple times, making many sketches of different images, studying the colors and how the shade formed, and returning to his studio to paint the final work. Unlike the Impressionists, his lines between a figure and the surrounding background are well defined by contrasting colors with his signature dots of paint; others termed it Pointillism. "He preferred the term Divisionism—the principle of separating color into small touches placed side-by-side and meant to blend in the eye of the viewer."[4]

Paul Signac

Paul Signac (1863-1935), born in Paris, originally planned to be an architect until he went to an exhibition of Monet's art, became inspired to study art, and become a painter. He started by painting landscapes and watercolor scenes in France. Later, he met Georges Seurat and developed into an avid supporter of Seurat and his theories of color and painting methods, electing to paint with the small dots of Pointillism instead of the Impressionist's shorter brushstrokes. Many deemed their work Neo-Impressionist; Signac believed he and Seurat painted more authentic colors and reflective light because they followed the scientific rules about how the eye perceives light and blends color, which he named 'optic mixing.'

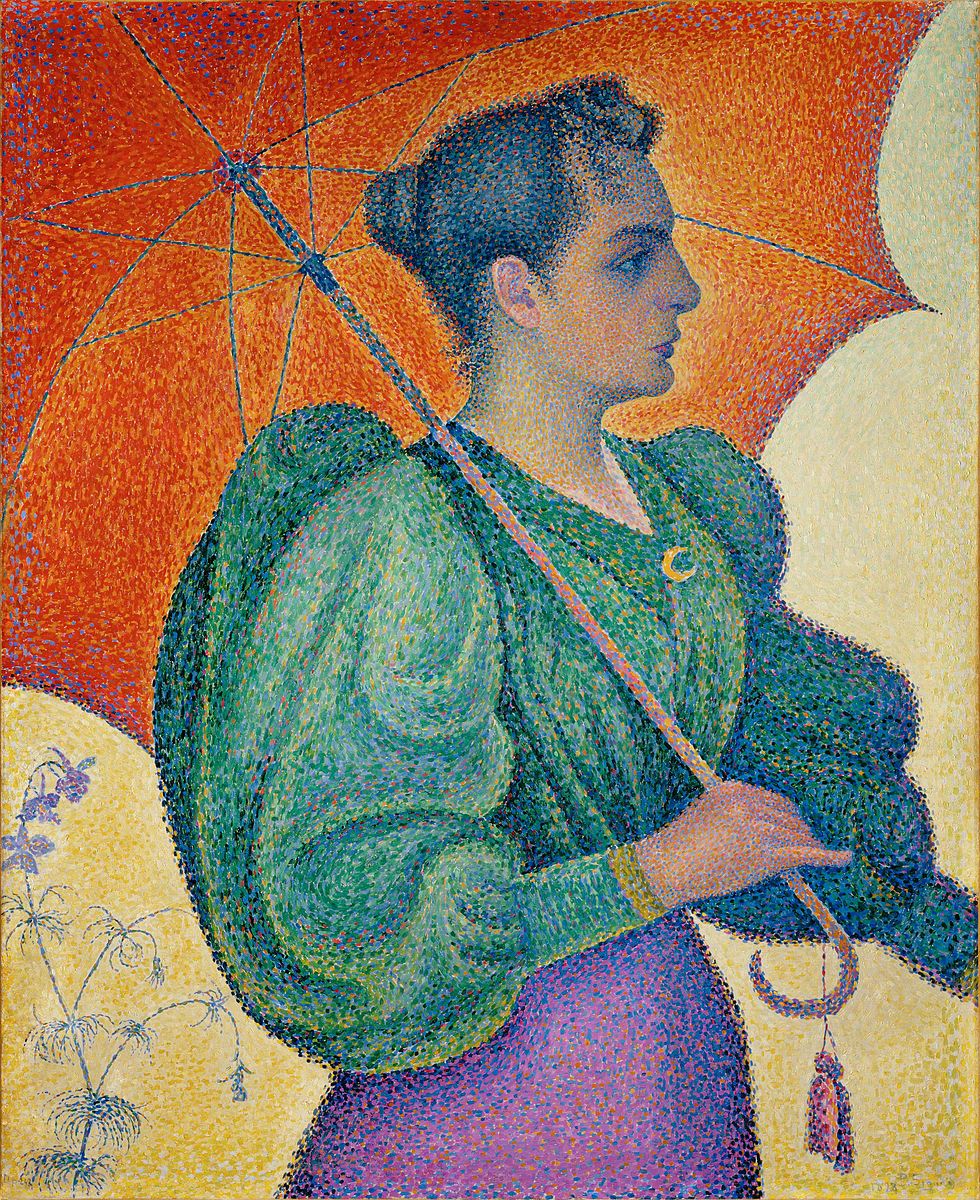

After Seurat died, Signac traveled extensively in Europe, making sketches of the scenery he encountered, returning to his studio to paint on his canvases. In this part of his life, he moved from the small dots advocated by Seurat to a style of small square dabs of color, similar to mosaic tiles. He continued to experiment with pen and ink drawings, etchings, and lithographs. The Woman with a Parasol (4.4.8) is an image of Signac's wife in a pose similar to the one the Impressionist painters used; however, it was painted entirely differently. He used a vibrant set of contrasting colors and juxtaposed green and orange with purple and yellow. He does not give the image an illusion of depth, instead a relatively flat look dominated by the woman's unusually large puffy sleeves, the stylized flower behind her adding a decorative element.

One of the seaports Signac frequented was Saint-Tropez. He was constantly railing against political agendas, fighting for different causes, and painted In the Time of Harmony (4.4.9) as his vision of utopia for the future. The people are portrayed in an idyllic place; painting, playing different games or reading, representing the utopian future. The artist himself is plucking a fig from the tree, and his wife is giving fruit to a child; the men are shirtless, everyone in relaxed poses, all in contrast to the stiff, straight images of Seurat's painting in the park. The colors are muted with few individual shadows, the darker section all shaded by the tree, and the rest of the painting in the bright sun. The critics did not like the painting, some calling it naïve, too political, and even hackneyed.

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), born in the Netherlands, is considered one of the most famous figures in art history, a person with a long history of a tortured mind who committed suicide when he was only 37 years old. He was unsuccessful as an artist in his lifetime, becoming accepted only later in the 20th century when others recognized his talents. As a young man, he tried other vocations until deciding to become an artist, teaching himself by copying prints to learn the basics of drawing and moving to landscapes and people who worked in the fields. Van Gogh had an unusual relationship with his brother Theo who supported him throughout his life, giving van Gogh financial support and trying to help him sell his art. Van Gogh wrote volumes of letters to his brother, providing recorded information about van Gogh's life, his feelings, and his artwork.

Van Gogh moved to Paris in 1885, and after seeing the work of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, he began to lighten the colors on his palette and used a broad, broken style of brushstrokes. He focused on self-portraits, obsessively painting over twenty of them in a short time, exploring uses of color, and building bolder contrasts. Van Gogh became friends with Gauguin, Pissarro, and Seurat, painting over 200 paintings in only two years, then feeling he had exhausted Paris, moved to Arles in 1888. Here, he painted his most successful works, inspired by the sunlight and landscape of the area, incorporating vast swaths of yellow in his paintings.

Gauguin visited him in Arles, the two arguing frequently, one altercation leading van Gogh to cut off his ear and send it to a woman both van Gogh and Gauguin knew at a local brothel. Gauguin left the area, and van Gogh suffered an acute mental breakdown. He went to Saint-Remy and checked himself into the mental asylum, painting constantly, creating works incorporating his famous swirls seen in Starry Night. In 1890, he left the asylum to be near a doctor who would treat him; however, in July, he was no longer able to cope with his continuing depression and mental issues, so he committed suicide.

…to know van Gogh is to get past the caricature of the tortured, misunderstood artist and to become acquainted instead with the hardworking, deeply religious, and difficult man. Van Gogh found his place in art and produced emotional, visually arresting paintings over the course of a career that lasted only a decade.[5]

Wheat Fields with Cypresses (4.4.10) is another example from his planned oeuvre based on central themes; this one represented his concept of the area around St-Remy and Arles as a pattern of how Provence should look with cypress, olive trees, and grapevines. The painting demonstrates the conflicts in his work, to paint an interpretation of the physical world as it existed yet incorporate the spiritual ideas working in his tormented mind. The single verticality of the cypress is counter to the horizontal movement of the wheat field and mountains as the clouds swirl randomly through the sky. Van Gogh painted five different scenes of sunflowers when he was in Paris and seven more in Arles, one of the most famous of his sets. The sunflowers are all similar, differing in number and position. When he was in Paris painting sunflowers, some of the blossoms were laying on the table, and in Arles, he positioned the flowers in vases.

Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (4.4.11) was painted at Arles. Van Gogh used shades of yellow, his favorite color at the time, demonstrating how he could use a minimal palette to create a wide variety of images. During this period, van Gogh was one of the first artists to use new synthetic forms of yellow, a broadened set of tones as opposed to the traditional yellow artists made themselves.

While he was in Paris, van Gogh painted over twenty portraits of himself to improve his painting techniques. He used cardboard for this image, Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (4.4.12). Van Gogh told others he bought a good quality mirror, so he had a well-reflected image to paint. At this time, he was also studying the color theories of the Post-Impressionists and experimenting with brushstrokes. Van Gogh is seen in summer-style clothing with a straw hat; one eye painted blue and one green. He primed the cardboard with streaks of purple, a color that faded and initially provided a strong contrast to his yellow hat.

After coming home from the hospital, Van Gogh painted Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (4.4.13) and recovering from cutting off his ear. Although sitting in his bedroom, Van Gogh still wears his coat and hat, and it is unknown if it was cold inside or if he just chose to wear them for the portrait. In the painting, his right ear appears with the bandage; however, his left ear was actually severed; Van Gogh probably painted a mirror image of himself. Behind him is an unfinished canvas. Shortly after this portrait was completed and his neighbors protested about his behavior, he was taken to an isolation cell in the hospital, later going to the asylum at Saint-Remy.

.jpg?revision=1)

Bedroom in Arles (4.4.14) was a painting of van Gogh's bedroom when he lived in the yellow house in Arles. He kept the room simple, minimally furnished with his pictures on the wall, and used bright colors, although the colors are somewhat muted today from age. For example, the door was originally purple and now has faded to blue and the walls were brighter violet. The corner skew on the rear wall was not intentional; the wall was made that way; however, in one of his letters to his brother, he mentioned that he did not add shadows and painted the room with a flattened look similar to a Japanese print. He also noted how much he liked the painting of his bedroom and later painted two other versions.

Van Gogh lived in the asylum when he painted Starry Night (4.4.15), his most famous painting, a view out his window at night. In letters to his brother Theo, he discussed what he could see out his iron-barred window at night, the darkness and shadows. He stated, "Why, I say to myself, should the spots of light in the firmament be less accessible to us than the black spots on the map of France?..Just as we take the train to go…to Rouen, we take death to go to a star."[6] The painting is dominated by the swirling patterns rolling across the sky, the bright moon on the left, and stars glowing in the night. Beneath the sky is the darkened village van Gogh saw from his room, the shadowy cypress trees on the side balancing the image. He used very short brush strokes to apply the thick pigments, madly creating the drama.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), born in France in the Pyrenees region, drew sketches in his schoolbooks at an early age, a talent recognized by his parents. He always suffered from congenital health problems, including breaks in his legs that did not heal properly, leaving them shortened. His grandmothers were sisters from an aristocratic family, and his parents were first cousins, marrying within the family and probably the cause for his inherited skeletal disorders.

His parents were wealthy, supported his art, and ensured he learned from well-known painters. He went to Montmartre, a place for artists and writers, unique lifestyles, a place he lived most of his adult life. He painted en plein air as other Impressionists did, only sitting in the streets and gardens of Montmartre, using prostitutes of the area for his models and cardboard as his canvas covered with large, loose brushstrokes. When the new Moulin Rouge cabaret opened in the neighborhood, Toulouse-Lautrec was commissioned to create advertising posters, painting some of his most famous works depicting singers and dancers and the new can-can dance.

Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from alcoholism, especially fond of absinthe he mixed with cognac. His walking cane had a hollow space to hold his liquor wherever he went. Toulouse-Lautrec patronized the plentiful supply of prostitutes, contacting syphilis which combined with his alcoholism, led to his early death. During his lifetime, he was a very prolific artist. In his career of fewer than 20 years, "he generated 737 canvases, 275 watercolors, 363 prints and posters, 5,084 drawings, 300 pornographic works, some ceramic and stained glass work, and an unknown number of lost works."[7] He developed his style using bright colors with long brushstrokes to emphasize contours, portraying people as they worked in the flamboyant nightlife of Montmartre.

With the population increase in Paris, the nightlife changed. The number of café/dance halls also increased, particularly in Montmartre, where men and women could drink and converse together, a previously forbidden activity. Here, especially in the larger clubs, Moulin Rouge and Moulin de la Galette, Toulouse-Lautrec drew, painted, and printed the often-tawdry nightlife of the cabarets and theaters, revealing the humor and sadness of the performers.

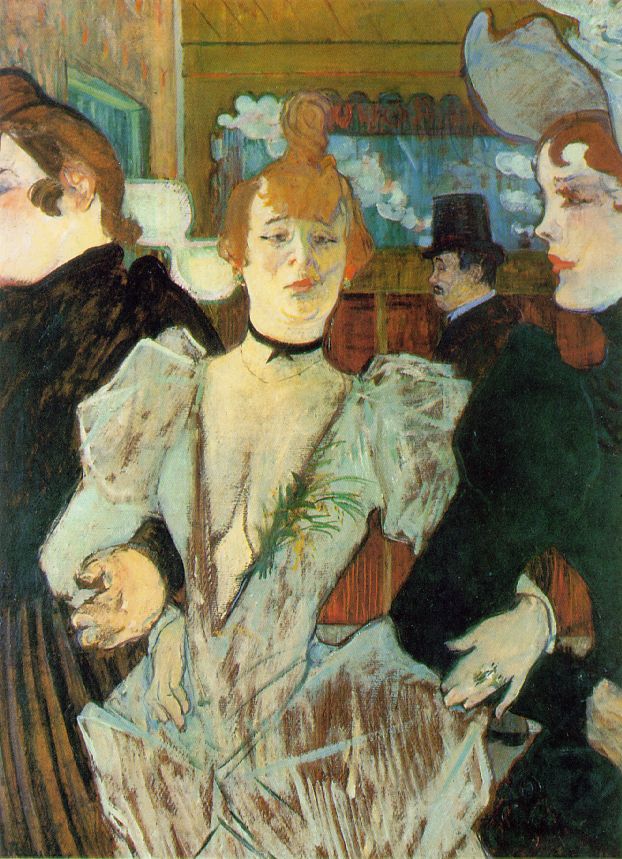

One of the Moulin Rouge stars performing the new can-can dance was the dancer, Louise Weber, also known as La Goulue (The Glutton) (4.4.16). In the painting, she is entering the Moulin Rouge with her sister and her lover. Her face is ashen, saddened, Toulouse-Lautrec liked to capture feelings reflected in faces. He frequently cropped the images and used bold lines to flatten the painting into a style reflected in Japanese woodblocks.

Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (4.4.17) was a poster advertising a dance at the cabaret, La Goulue in an aggressive pose doing the can-can, her specialty that she frequently performed without the benefit of underwear. The poster only used four colors, the audience in black forming the background as a contrast against the stark white of her lacy undergarments. The large M at the beginning of the repeated name was an unusual technique. About 3,000 copies of this poster were made and pasted around Paris, making Toulouse-Lautrec famous and earning him attention and multiple offers to make posters.

_1891.jpg?revision=1)

At the Moulin Rouge (4.4.18) demonstrates the nightlife of the cabarets, both men and women as patrons. In this painting, Toulouse-Lautrec used strident colors in different places lifting parts of an image out of the recesses of darkness. The bright orange hair of an entertainer brings the focus of color to the center, while the ghoulish green face on the side moves the eye and haunts the imagination. The cropped brown table covers much of the painting, anchoring the people seated at the table. Looking into the mirror in the background is the dancer, La Goulue, a frequent image found in his paintings. The cabaret loses its glamour, seemingly filled with sad people bleakly sharing their miseries.

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) was born in France during a time of political unrest, some instigated by his relatives. His father was jailed for the attempted murder of his mother, and the family fled to Peru, a place with wealthy relatives where he lived in privilege. After political conflicts swept through Peru, they returned to France. He was trained in the military, married, started an unsuccessful business in Denmark, had several children, and was asked by his wife to leave after eleven years of marriage. Returning alone to Paris, he started painting, becoming friends with other artists. He did enter work in one of the Impressionist shows; however, he disagreed with other artists like Seurat and the way he painted. Breaking ties with the Impressionist community, he began to experiment and was termed a primitive artist. He moved to Brittany, painting works with broad, flat areas of color based on symbolic concepts. In the late 1880s, he became friends with van Gogh; although they competed, they both pushed the boundaries of color in their paintings.

After van Gogh died, Gauguin became unhappy with the constant critics of his work and decided to move to a faraway place where he could paint as he wanted, going to Tahiti and the French Polynesian islands. Here he used color, and scenes with concepts of Western art and Eastern sources. His work became more symbolic as he told others, "explanatory attributes-known symbols-would congeal the canvas into a melancholy reality, and the problem indicated would no longer be a poem."[8] When he returned to Paris for a while, he made woodcut prints and experimented with colors and inks, bringing Tahiti's exotic and mysterious vision. Although Tahiti was not precisely as imagined as over half of the people were killed by European diseases, he returned to Polynesia, still searching for paradise until the end of his life.

When he was in Brittany, he wanted to avoid the influence of the Impressionists, painting The Vision After the Sermon (4.4.19), a biblical-based subject of an angel and Jacob wrestling in front of a female audience in Breton. Using a method termed Cloisonnism based on flat forms, he arranged the women across the painting, dominated by the flat white hats. A tree juts diagonally dwarfing the wrestling event, all of the colors brightly contrasting, without shadows.

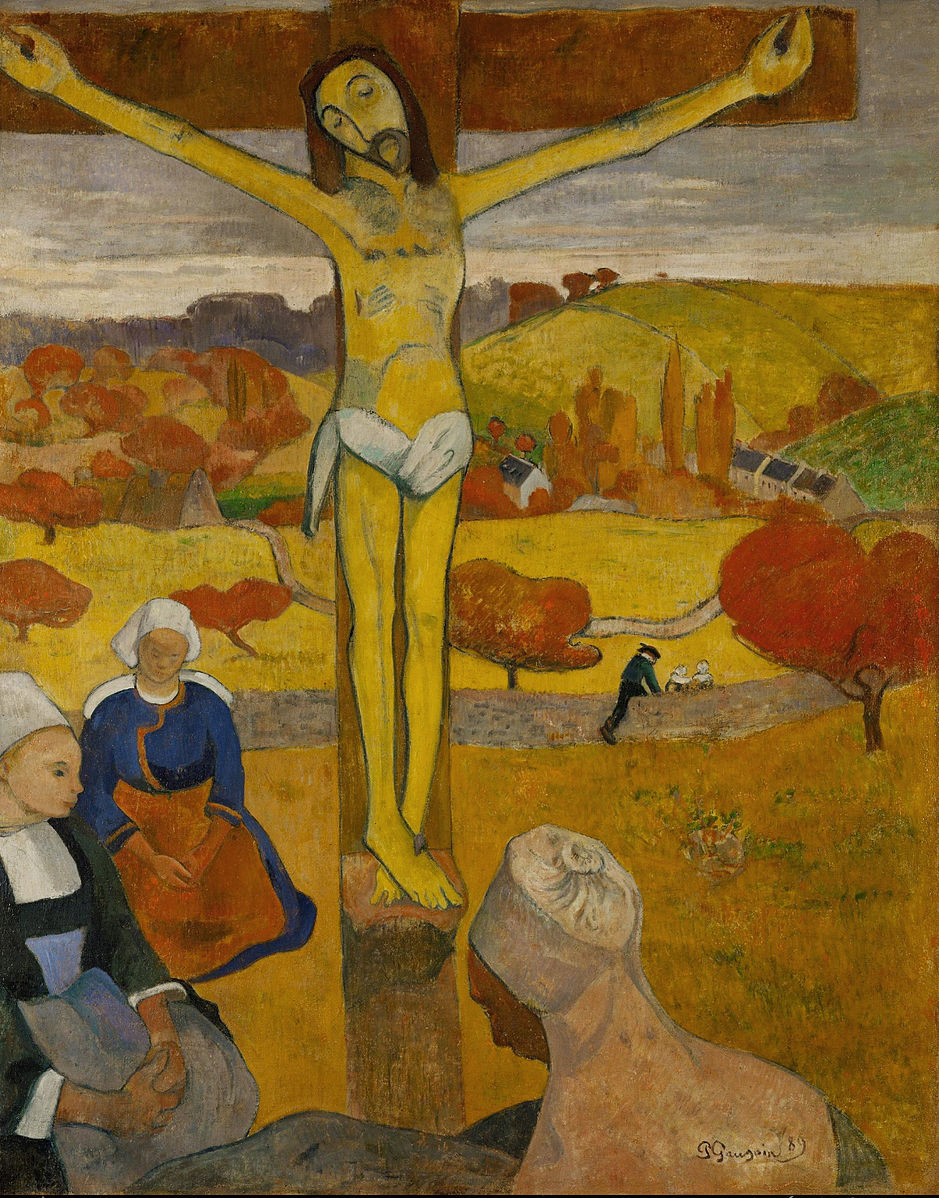

Gauguin sets the crucifixion scene of The Yellow Christ (4.4.20) in the countryside of Brittany, the women in typical clothing waiting at the bottom of the cross. He used flat autumn colors of yellow, amber, and browns in the painting, the thin, stretched body on the cross painted in unearthly yellow, unnatural colors that work with each other. Gauguin applied bold, dark outlines to counter the flat look of the figures. He also painted The Green Christ in the same area, both key images representing Symbolism.

Gauguin loved the bright colors he found in Polynesia, lavish flowers, unusual and exotic fruit, blazing sunsets reflecting on the seas, and women he considered mysterious. When paintings from Gauguin's journey to Tahiti were displayed, one of the critics was interested in Gauguin's methods and asked him to describe them. Gauguin answered,

I arrange lines and colors so as to obtain symphonies, harmonies that do not represent a thing that is real, in the vulgar sense of the word, and do not directly express any idea, but are supposed to make you think the way music is supposed to make you think, unaided by ideas or images, simply through the mysterious affinities that exist between our brains and such arrangements of colors and lines.[9]

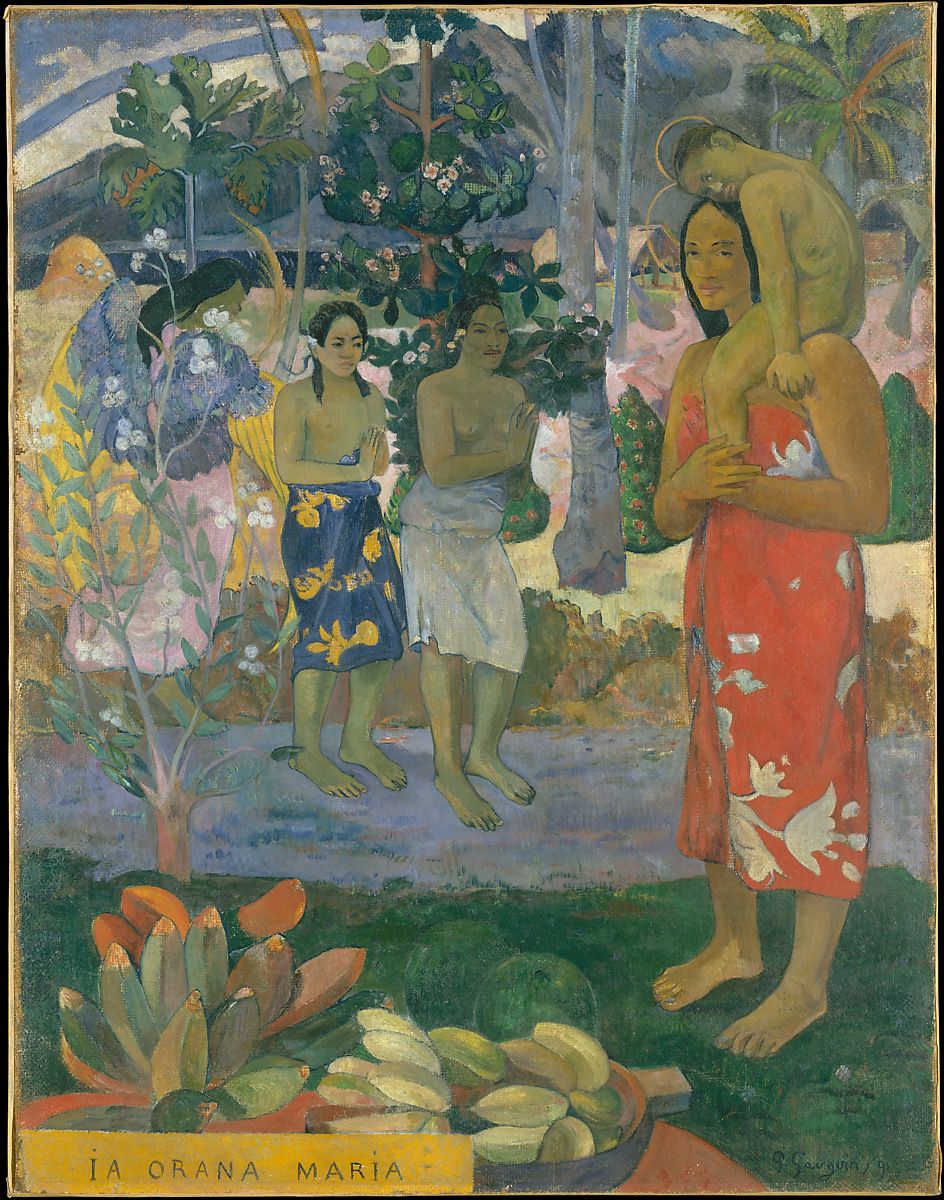

Ia Orana Maria (Hail Mary) (4.4.21) was Gauguin's first significant painting in Tahiti, and he sent a letter to his friend describing the painting as; A yellow-winged angel points out Mary and Jesus to two Tahitian women. Mary and Jesus are likewise Tahitians and naked, except for the pareo, a flowered cotton cloth tied to the belt as suits one's fancy. In the background are very dark mountains and blossoming trees. Foreground emerald green. To the left bananas…[10]

Gauguin used a mix of Christian and Tahitian rituals; the Madonna wears Tahitian clothing, and bananas sit on the typical altar. Gauguin often described Tahitian women as mysterious yet charming. When Will You Marry? (4.4.22) portrays two women, the one in the back, wearing confining clothing introduced by the missionaries. The other woman has a typical colorful skirt wrapped around the hips, a flower tucked behind her ear, displaying her interest in an admirer. She was also found in other paintings by Gauguin. He complimented the colors of the women and their dresses with large swathes of yellow and green.

Edvard Munch

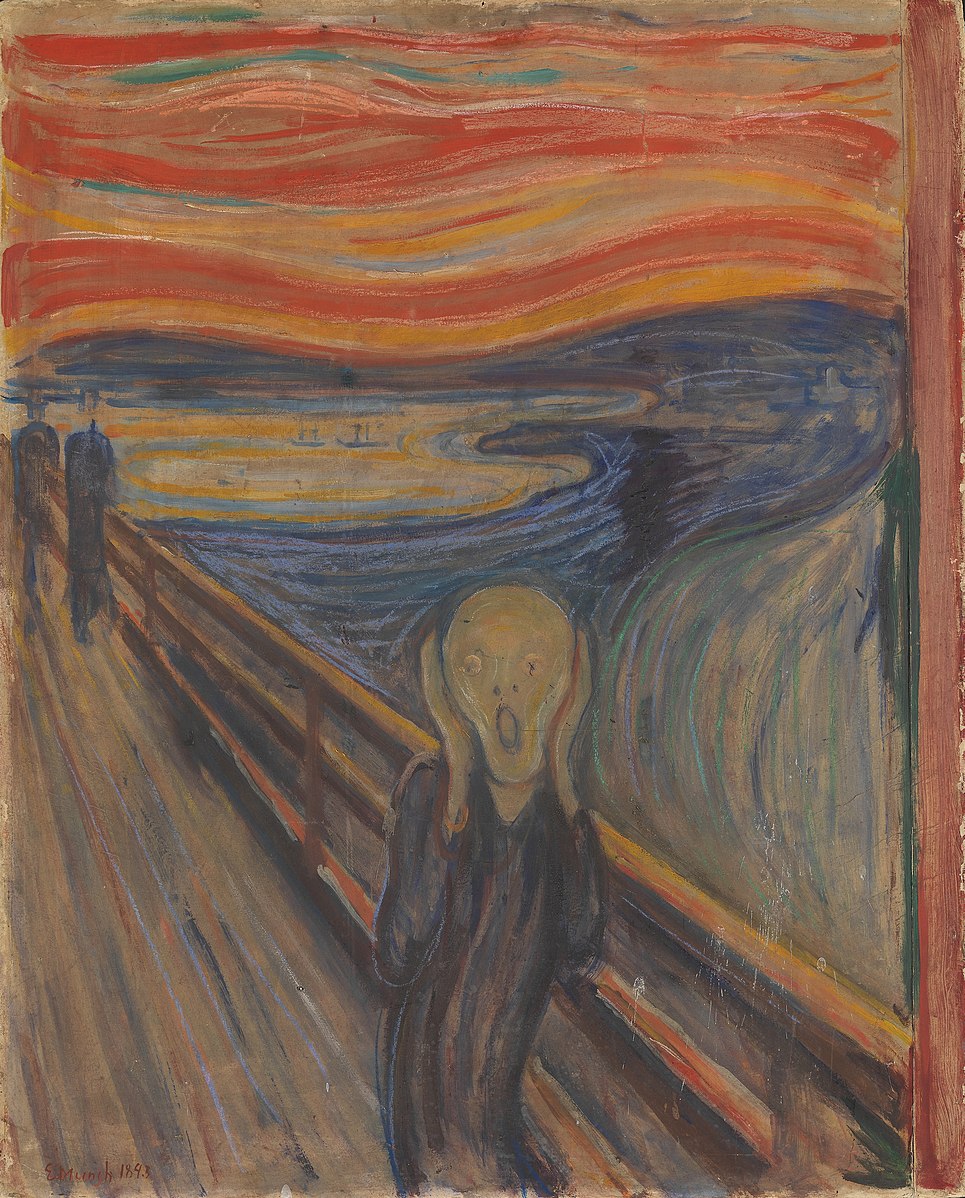

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), born in Norway, experienced a childhood filled with family illnesses of tuberculous and insanity. He studied at the Royal School of Art in Norway, then traveled to Paris and worked with van Gogh and Gauguin, exploring how they used color and composition to express emotion before returning to Norway to paint. Munch never married and lived by himself for twenty-seven years before his death. He was exceptionally prolific yet did not want to part with his works. When he died at the age of eighty, locked in his house, local authorities found; "a collection of 1,008 paintings, 4,443 drawings, and 15,391 prints, as well as woodcuts, etchings, lithographs, lithographic stones, woodcut blocks, copperplates, and photographs."[11] However, even with all he created, he is mainly known for one image – The Scream.

The symbolism expressed by Gauguin soon became incorporated into the work of some of the younger artists throughout Europe, wanting to express an idea, feelings, or visions instead of the realistic natural world. They believed the symbolic ideas of a painting resulted in emotional experiences as depicted through how color and lines were formed to express the feelings. Early in his career, after returning from Paris, Edvard Munch adopted the concepts of Symbolism and painted a series, The Frieze of Life, about the despair and loneliness of life.

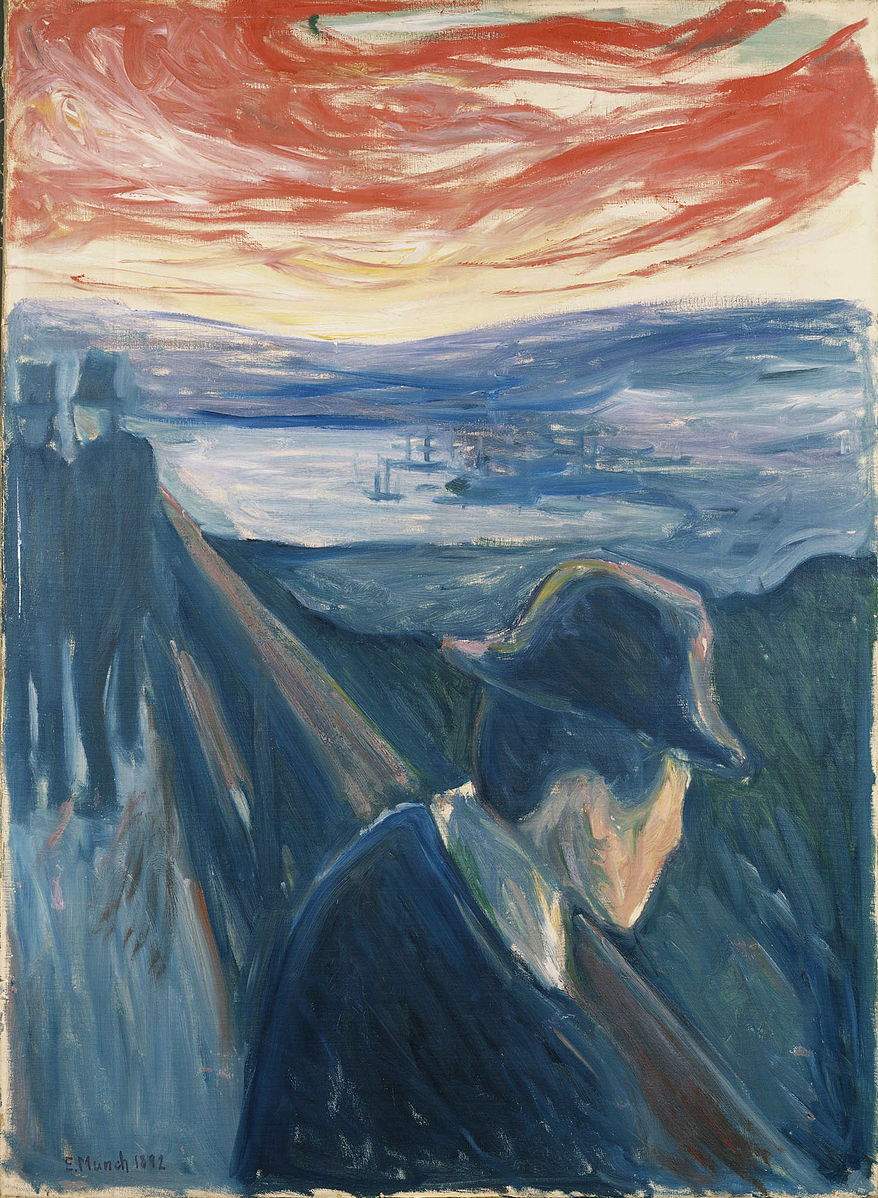

Munch used the Oslo bridge in many of his paintings, as a backdrop to portray tormented mental images. He created twenty-two pieces of art for the Frieze of Life, all with titles demonstrating misery. There are multiple interpretations about Munch's sky and why he consistently used the bold colors in an otherwise dark palette. Munch wrote in his diary,

"I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun was setting – I felt a wave of sadness – the Sky suddenly turned blood-red…I felt as though a vast, endless scream passed through nature."[12]

In Despair (4.4.23), the lonely man stands on the bridge, appearing tired, worried, or with more profound feelings of grief and pain. Many believe the man resembled Munch, perhaps expressing his feelings of despair. Munch used the railing on the bridge to move the viewer through the otherwise flat painting.

The Scream (4.4.24) is Munch's most famous painting, the symbolic figure standing on the bridge, wracked by emotions and screaming into the empty air. The railing strongly crosses on a diagonal as the figure curves with the movement of the background.

Anxiety (4.4.25) was also painted on the bridge, with the water in the background, using the same dark hues and lines to define the sky, mountains, and sea. In the Scream, a single person expresses emotions, while in Anxiety, a group of people seem to share their desperation. In all three paintings, the town and ships are barely visible in the background.

Japonisme

Japonisme was a term defined by one of the French critics describing the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e art on European artists and their interest in woodblock prints. Both Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists used the techniques and styles, including Degas, Monet, Cassatt, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Japanese ports started trading again with Europe in the mid-1800s, and artists buying small vases or cups saw how the images were asymmetrical and had empty spaces or broad perspectives. The European artists experimented with exaggerated colors or flattened perspectives, undulating lines, and contours, often creating paintings or prints based on a specific Japanese image or outline.

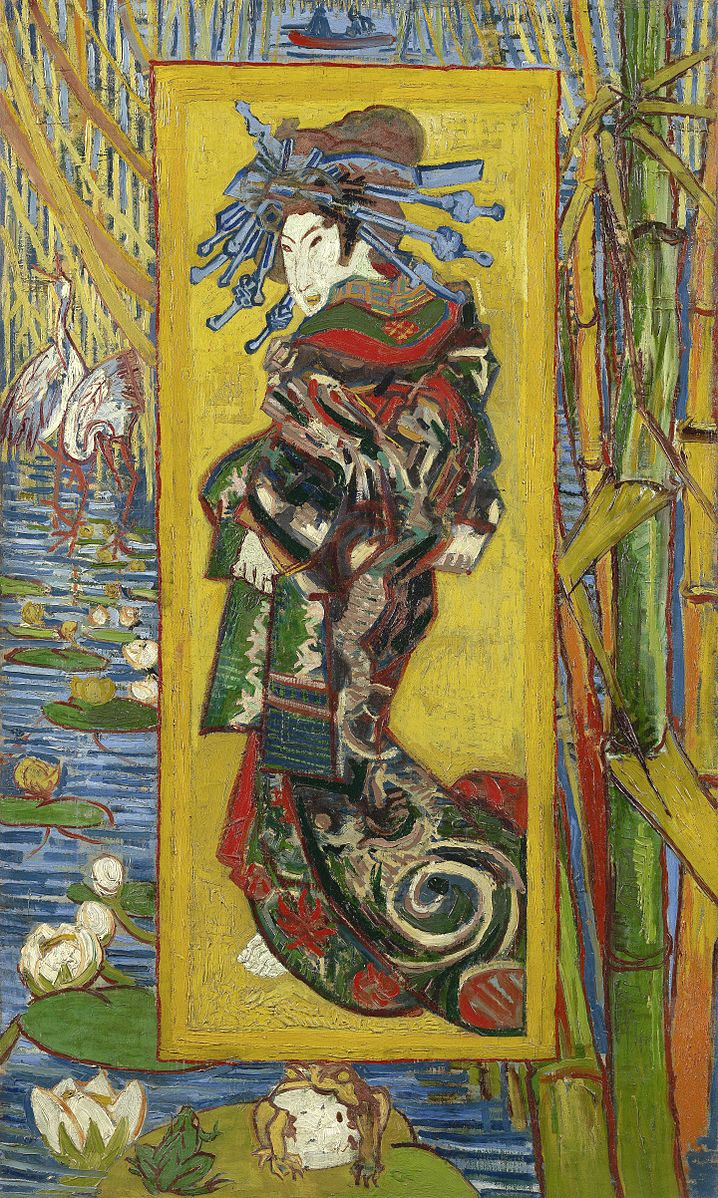

Vincent van Gogh and his brother were avid collectors of Japanese prints, and he painted The Courtesan (4.4.26 and 4.4.27) based on an image on a magazine cover. Painted in van Gogh's traditional bright colors, he added the dark contoured lines from the print. He surrounded the figure with characteristic Japanese images; bamboo, water lilies, cranes, and frogs. Many historians believe he selected those images because grue (crane) and grenouille (frog) were slang terms for a prostitute.

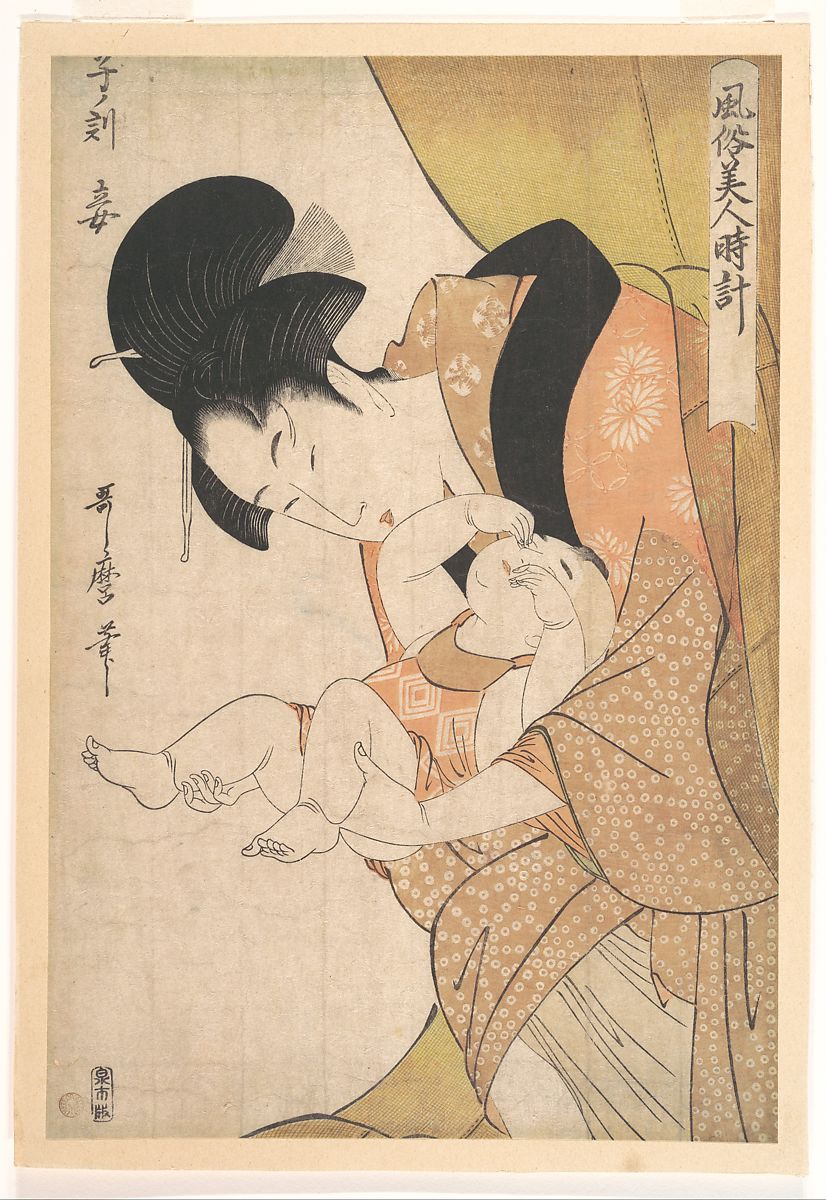

Figure \(\PageIndex{26}\): Courtesan by Keisai Eisen (Woodblock print, ink, and color on paper, 23.8 x 33.7 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{26}\): Courtesan by Keisai Eisen (Woodblock print, ink, and color on paper, 23.8 x 33.7 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\): The Courtesan by Vincent van Gogh (1887, oil on canvas, 100.7 x 60.7 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\): The Courtesan by Vincent van Gogh (1887, oil on canvas, 100.7 x 60.7 cm) Public Domain

Mary Cassatt generally focused on the lives of women and everyday events as in Maternal Caress (4.4.29). She saw the exhibition of woodcut prints and created a set of etchings based on Japanese prints. Her mother and child were done with a similar muted palette, a focal color, white, with accents of black with detailed black lines. Both mothers lovingly play with their children.

During the Post-impressionist period, France was alive with artwork and artists, spawning multiple movements as people experimented with paint, brushstrokes, lines, and themes. The Post-Impressionist grew from the Impressionist concepts, bringing their ideas of color and light, rejecting limitations in the way they painted and their lifestyles.

[1] Cogeval, G., Patry, S., Guegan, S. (2010). Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, and Beyond. DelMonico Books, p. 67.

[2] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pcez/hd_pcez.htm

[3] Retrieved from https://www.artic.edu/artworks/27992/a-sunday-on-la-grande-jatte-1884

[4]https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437658?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=seurat&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=3

[5] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/vincent-van-gogh-the-starry-night-1889/

[6] Retrieved from https://www.vincentvangogh.org/starry-night.jsp

[7] Angier, Natalie (6 June 1995). "What Ailed Toulouse-Lautrec? Scientists Zero In on a Key Gene". The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1995/06/06/science/what-ailed-toulouse-lautrec-scientists-zero-in-on-a-key-gene.html

[8] Myers, N. “Symbolism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/symb/hd_symb.htm

[9] Cogeval, G., Patry, S., Guegan, S. (2010). Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, and Beyond. DelMonico Books, p. 130.

[10] Dorra, H. (1952). Ia Orana Maria. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 10(9), 255-260.

[11] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/edvard-munch-beyond-the-scream-111810150/

[12] Retrieved from https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0144.1