4.3: Impressionism (1874-1886)

- Page ID

- 120749

Introduction

Impressionism significantly changed the process of painting, influencing artists around the world. The main passion the Impressionistic artists all shared was light and color, how the light made colors intense or changed the hue. They also wanted to capture the moment, sitting outside en plein aire, working with quick, dynamic brushstrokes on brushes loaded with paint, a new concept of nature and people, and how everything was portrayed on the canvas the impression of a view instead of smoothly blended details. The artists discovered how dark shadows, gray cloudy skies, or deep water had a continually changing variety of colors. The colors brushed with freedom formed the lines and contours, short, quick brushstrokes formed into recognizable objects.

Artists had long painted outdoors, usually sketching partial images and completing them on larger canvases or panels in the studio. The Impressionist artists want to work outside, capturing a moment in time and exploiting the natural light found plein aire. A few crucial inventions facilitated the movement. Easels had long been wooden frames an artist rested a painting on in a studio, not portable. In the 19th century, the French Box Easel was invented, portable easels set on telescopic legs, a paint box to carry supplies, and a palette built into the easel, perfect for the artist trekking through the fields and hillsides searching for the ideal light. In 1841, John Goffe Rand invented the paint tube, a revolution for artists and an essential commodity for the Impressionists. He was an artist who was aggravated by how quickly his paints dried out or spoiled. Paint, at the time, was stored in breakable glass jars or pig bladders which were not resealable and hard to use. He invented a squeezable tube made of metal, preserving the paint's fluidity and removable in small amounts. Now the artists could take tubes of different colored paint into the fields and easily squeeze out the amount they needed.

The history of the Paris salons and Impressionism were intertwined; the Salon's rejection of the set of artists forced the independent artists to circumvent the salons and create their exhibitions and destiny. The Salon held annual shows, and in 1863, 5000 works from 3000 artists were submitted for entry; only 1000 were accepted based on the traditional and expected styles of art. A few young painters had one or two paintings, still conservative paintings; however, they generally met rejection. During this time, the painters became friends, learning from each other and finding new inspiration, although they also found poverty except the few from wealthy families.

From 1874 to 1886, the Impressionists held their shows, apart from the Salon and its standards. The critics panned the artwork declaring the colors unblended, with little detail and visible brushstrokes, not artists deserving any serious attention. Degas became the principal promoter for the group, getting the artists to join together, holding their shows. Despite his objections, the term Impressionists was forever assigned to the new style of artistry. One of the paintings Monet entered was Impression Sunrise, where a critic derided the painting as just an impression, not a completed painting, just indistinct and blurry forms. The other artists and Monet started to call themselves Impressionists, and the name remained forever.

Claude Monet

Claude Monet (1840-1926), born in France, was not only a founder of Impressionism but the most prolific painter who adhered to the principles of the movement. Monet's work focused on landscapes, the scenes of the Normandy coast, and the activities of people in Paris, becoming marginally successful in his early years. He became friends with some of his classmates and acquaintances who the Salon also rejected. They formed their exhibitions. After her death, Monet traveled around France, painting familiar scenes and people, especially his wife Camille and his second wife, Alice. He frequently worked with other painters, sitting outside observing the same panoramas yet resulting in different versions. While documenting the beauty of the countryside, he painted the same vista multiple times, capturing the essence of a location in different seasons and the changing light numerous times of the day; the evening light in fall or the morning sunrise in spring, focusing on the shadows and color.

In his early days, Monet went with Renoir to the resort on the Seine River, a place for Parisians to socialize, swim, boat, and eat. La Grenouillere (4.3.1) is one of the several iterations of paintings in the same locale they both painted. Monet used color to develop the varied shadows in the painting, still more realistic than later work.

Woman with a Parasol (4.3.2) demonstrates Monet's ability to paint figures. This image of his wife, the softness of her pink dress against the billowy sky, was painted outdoors, using energetic brushstrokes of vivid colors for the flowers.

In 1883, Monet bought his property located in Giverny. He lived there for forty years, transforming the site of an old apple orchard into a spectacular garden of color and symmetry, with diverse perspectives from every view. Monet planted the garden with large flowerbeds that changed with the season, iron arches for roses, and trees of all types. Most of the garden was not manicured; instead, he let it grow wildly; however, the water garden was his masterpiece. He first started with a small pond, a home to his water lilies, enlarging it by diverting water from the nearby river, building the Japanese bridge, and adding the spectacular trees and vegetation around the perimeter. Monet spent twenty years painting all aspects of the lily pond and its environs, "Monet would dedicate himself less to flowers than to reflections in water, a kind of inverted world transfigured by the liquid element."[1] As a passionate horticulturist, Monet planned, planted, and built the water lily pond, a beautiful reflective garden with wisteria, weeping willows, bamboo, and the famous water lilies. He spent hours painting in the garden, finishing over 250 images of water lilies. He became financially successful and hired a cadre of gardeners; one gardener rowed around the pond each morning, positioning the lily pads to optimize their appearance.

Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies (4.3.3) is one of twelve bridge paintings. The bridge became an outline for the water lilies and their reflection in the still water. Monet used hues of greens and blues as the primary colors for the paintings, making the small colorful lilies themselves the accent points, all painted with his textured brushstrokes.

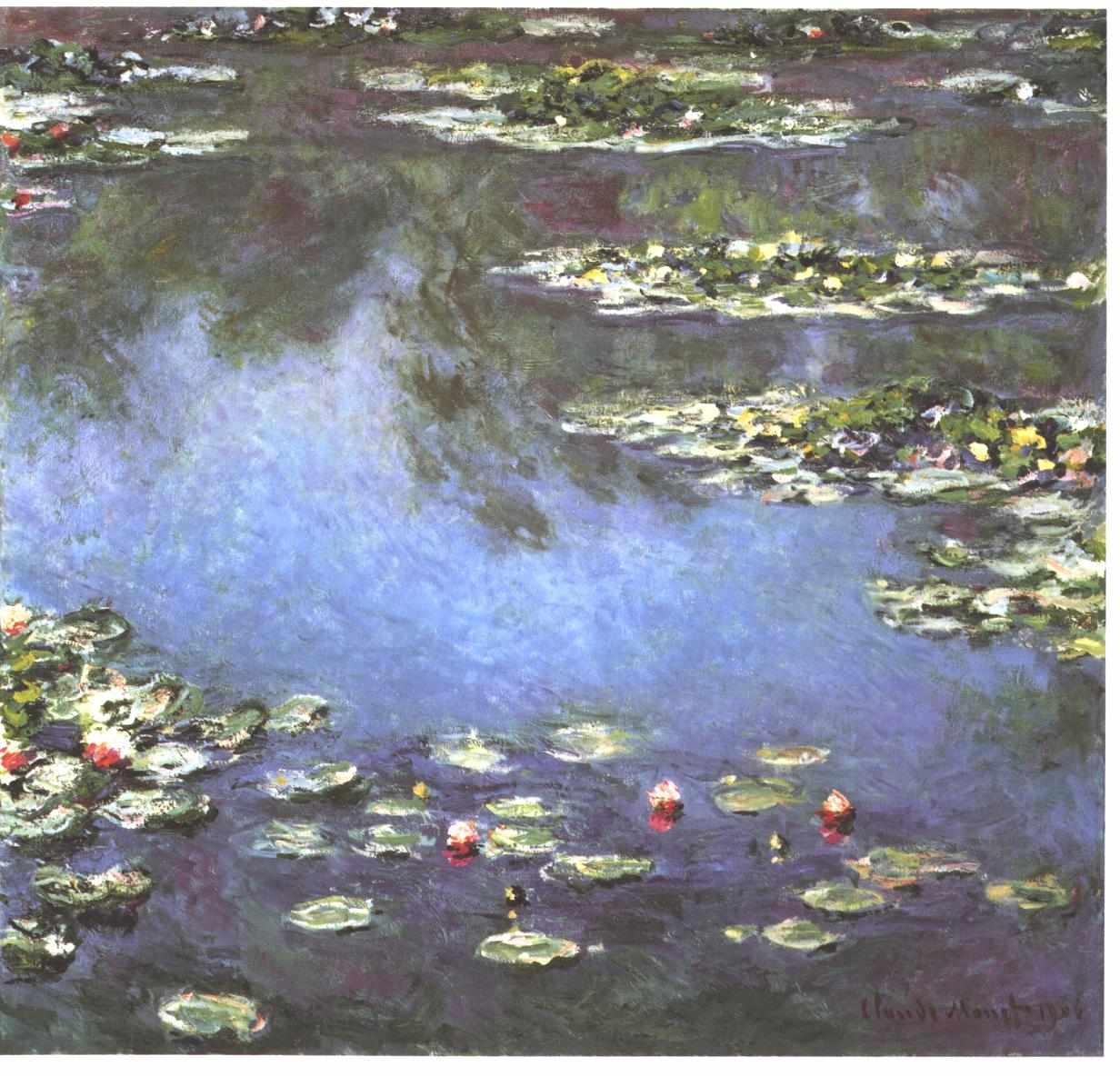

Waterlilies (4.3.4) demonstrate Monet's use of color and brushstrokes, the blue water running through the middle of the painting, reflecting the sky and surrounding trees. He painted darker tones for shadows to highlight the bright colors, optimizing the time of day.

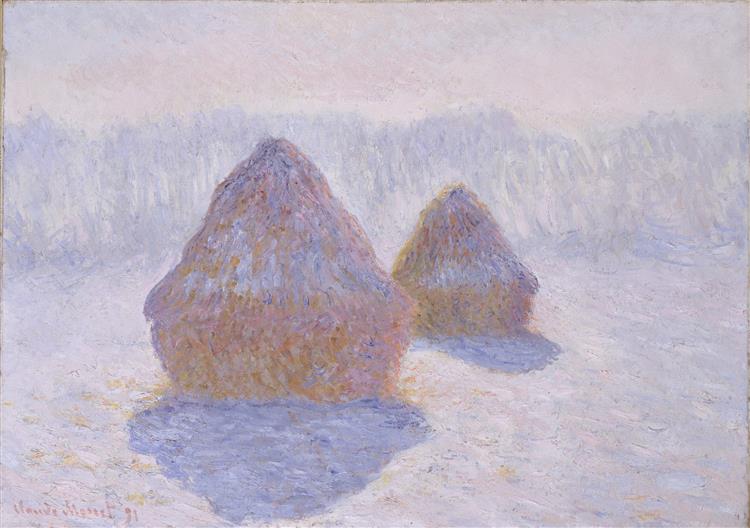

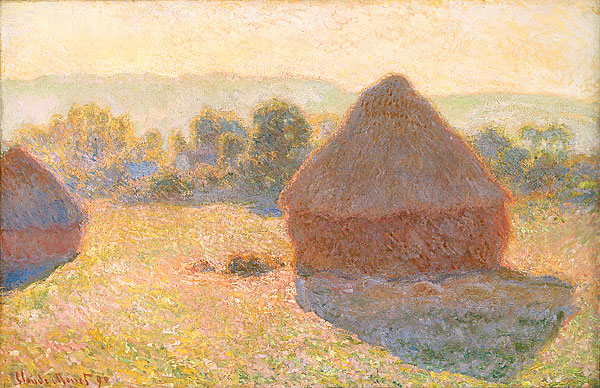

Haystacks (Effect of Snow and Sun) (4.3.5) and Haystacks Midday (4.3.6) are two of the thirty paintings completed by Monet about haystacks. The haystacks were located in Giverny near his house. One of the images is set in winter after a snowfall, and the other is shortly after harvest, under the midday sun. Both paintings were probably done at similar times as the shadows cast by the haystacks are comparable. The set of work was the first he exhibited in the series. He wrote to one critic, "I am working very hard, struggling with a series of different effects (haystacks), but at this season the sun sets so fast I cannot follow it. . . The more I continue, the more I see that a great deal of work is necessary in order to succeed in rendering what I seek."[2]

Monet rented a room across the street from the Rouen Cathedral to capture the changing light of day on a building. He set several canvases up on the curbside, painting on each canvas as sunlight progressed throughout the day across the face of the cathedral, a total composition of thirty canvases. Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Sunlight) (4.3.7) and Rouen Cathedral.

Façade (Sunset) (4.3.8) are examples of the effect of the changing light on the surface of the cathedral. His short brushstrokes defined the sculpted stone, a blue-gray in the early morning, bright oranges and yellows when the sun shone on the façade. He completed each painting in his studio, adjusting them to ensure their interrelationships.

Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), born in France, came from a wealthy family and was educated in all the classics of Greek and Latin, and influence is seen in his early art training. Degas entered an early historical painting into the Salon and was successful, in painting other conservative works. Because of his family's wealth, Degas did not need to sell his work. He moved to paint scenes of actual life, freed to follow his whims, and he focused on ballet dancers, café activities, and horse racing, depicting the movement of the human or animal's body. Although he was associated with the Impressionists, he thought the focus of painting outside all the time was ridiculous and told them constantly what he thought about it.

He also liked to paint from unusual vantages, cut off a figure, or frame the subject asymmetrically. Degas generally used oil paint, pencils, or pastels with different techniques, then added watercolor or gouache to create unusual textures on his surfaces. In his later years, an old injury impaired his eyesight, and he often turned to sculptures or landscapes without figures. The wax figures he sculpted were cast in bronze after his death. Degas also had a long relationship with Mary Cassatt, both of them painters of figures.

Degas repeatedly visited the opera house to watch the shows and visit backstage, mainly the dance studio. An example of his consistent focus on the dancers is The Ballet Class (4.3.9). Dancers finished the latest practice, sitting, stretching, and adjusting a piece of clothing, generally exhausted. Degas captured each unique dancer and how their body was positioned, the taskmaster teacher still standing with the baton he used to beat time on the floor. Degas used the lines on the floor to move the eye through the image, earning a reputation for his technique of painting floors. Paul Valéry wrote: "Degas is one of the very few painters who gave the ground its true importance. He has some admirable floors".[3]

Dancer Taking a Bow (4.3.10) is one of Degas's iconic images, a solitary dancer receiving accolades from the crowd as other dancers watch. Degas did not focus on any specific person; instead, he was interested in the form of the body and its positions. Using pastel to create the dancer gave her a light, airy and radiant feel, while the gouache brushed with thick strokes for the scenery forms a solid background. Degas used peach-colored paper, giving an overall glow, especially to the floor. The floorboards form a strong diagonal, sweeping across the image and mirrored by the scenery.

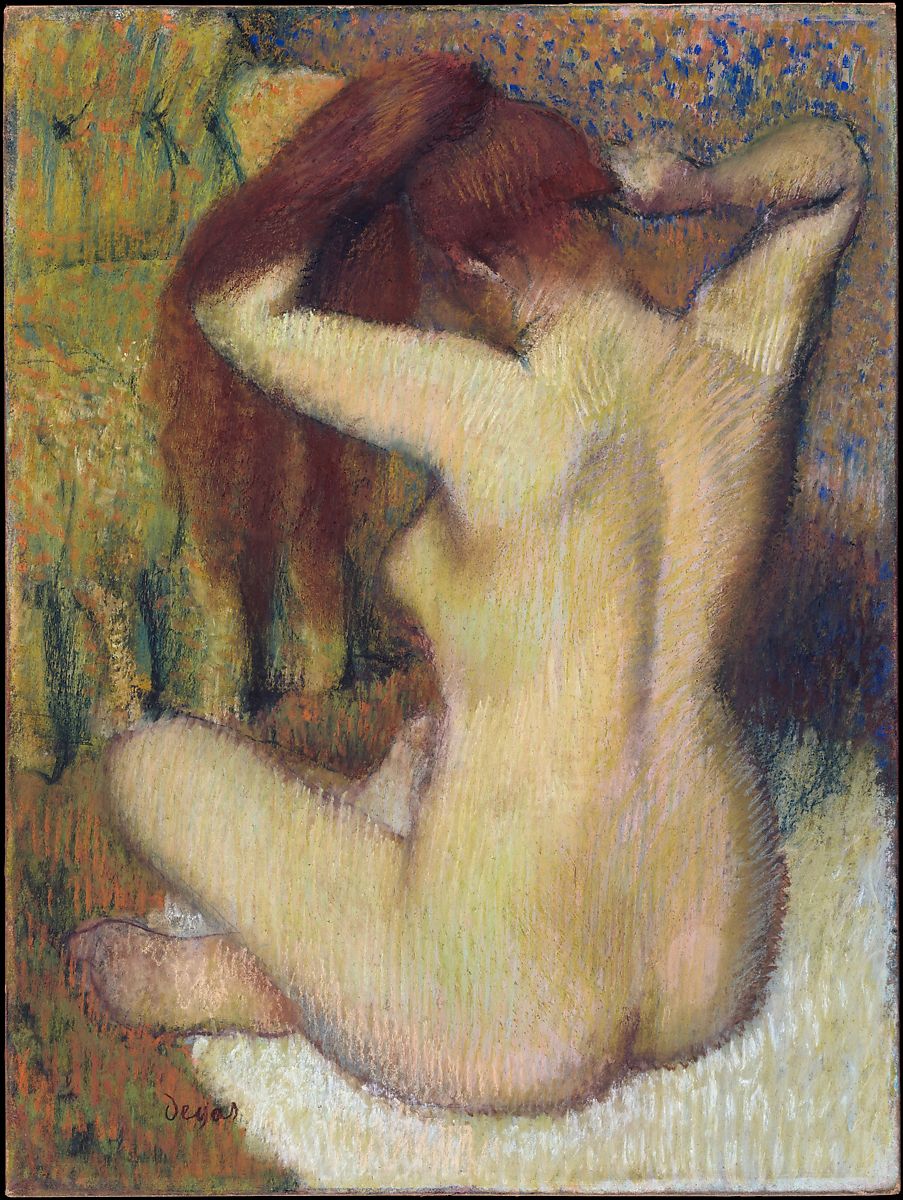

For the last Impressionist exhibition, Degas developed a new series based on female nudes in their dressing rooms, actively bathing or drying off, getting dressed, or combing their hair. He wanted to portray females performing ordinary activities, focusing on the curves and shapes of the body at that instant. He kept the background simple, unobtrusive to the action of the figure. Degas used pastels on light green paper to create Woman Combing Her Hair (4.3.11). Using a different technique, he applied pastels in multiple layers, rubbing each layer, so the minute fibers of the paper loosened and became part of the surface. The pink of the human flesh is evident as he used pale greens, a complementary color to create highlights.

Degas was always obsessed with racehorses, their muscular beauty, powerful movements, and variations of color. When he selected a scene, he usually painted several variations on different canvases. The recently discovered and published stop-action photography captured a horse's movement frame by frame, which Degas used to paint the horse's motion in correct positions. He studied horses at the track and on farms, filling his sketchbooks with images of horses. Before the Race (4.3.12) is one of Degas's three paintings created in the same setting. He depicted the horse's nervous energy before the race, painted in a muted palette with punctuations of color on the clothing of the jockeys.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), born in France, became one of the leaders of the new Impressionism movement. He displayed his talent early in life as an artist and a singer. Forced to work in a porcelain factory, Renoir frequently went to the Louvre to copy the masters. He finally was able to study as an apprentice, meeting Sisley and Monet. Most of his work represented an instance in time of the life of ordinary people, particularly women, whom he portrayed in a world of color and light. When Renoir and Monet started painting outside, studying the way the light reflected, they found that shadows were not black or brown; the colors of the shadows depended on the way the light reflected on the surroundings. Renoir painted scenes using brushstrokes freely applied with different colors. Late in his life, he had rheumatoid arthritis, limiting his ability to paint and pick up his brushes.

Luncheon of the Boating Party (4.3.13), set on a balcony along the Seine, became one of Renoir's most famous paintings. He frequently painted other artwork here by the river, one of his favorite locations. The scene includes some of Renoir's friends enjoying food and wine on an idyllic afternoon, a common sight in a place people went to row, bathe, or dine. The scene also reflected the changing society; women, artists, businessmen, and shopkeepers mingled in the cafes, no longer a place for only the elite. Everyone in the portrait was not gathered simultaneously; he had to paint different people as they were available, stretching over months. The seated woman with the straw hat, holding the dog, was Renoir's latest girlfriend, who became his wife. The painting not only portrays friends enjoying the day by the river; in the center is a marvelous still life of bottles, glassware, and a bowl of fruit. The rest of the meal is not part of the table; presumably, lunch was completed, and friends were focused on the conservations.

Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette (4.3.14) depicts a Sunday afternoon in Montmartre, an area with cafes and dancehalls. Moulin de la Galette was a place Renoir liked to visit, a site for the ordinary working-class, and he knew many of the people he used for models. His application of brushstrokes to create light and shadows is considered one of the best examples of Impressionism. He captured the dappled sunlight throughout the painting with colors and instilled a sense of movement in the dancers.

La Loge (4.3.15) is a painting demonstrating the interest in the spectacle of the theatre by society, a subject painted by many of the Impressionist artists. In Renoir's work, an elegantly dressed couple is seated in their box at the theatre. The man in the background appears to be looking at other people in the theatre. The woman politely sits and looks forward, her glasses in her lap, available for others to look at her. The theatre was not only a place to view a play or an opera, but a social stage to display one's status. Renoir used dark colors, bold brushstrokes, and positioning to build the drama into the couple's clothing, countering with delicate lace on her bodice and sleeves.

Alfred Sisley

Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), born in Paris, was sent to study business in London, where he spent three years then returned to France to train as a painter before meeting Renoir and Monet. He was not one of the well-known Impressionists; however, he did follow the principles and exhibited with the others. Sisley spent most of his time in the country and painted landscapes almost exclusively. He used a muted palette capturing a specific time of day or season outdoors with pale green, purples, blues, and pink.

Rue Eugene Moussoir at Moret: Winter (4.3.17) is one of a group with winter, snowy scenes from Sisley, a theme he continued throughout his lifetime. The street is set by the village hospital, a short distance from Sisley's home. Using a nuanced and soft palette, his brushstrokes change between broad movements along the roadway to small delicate strokes for the branches.

Allée of Chestnut Trees (4.3.18) portrays people spending a quiet afternoon strolling along the Seine, a pastoral scene. Sisley's short brushstrokes created the shapes, particularly seen in the leaves of the trees and how the blades of grass bend. He used a palette of bright colors with softer colors defining the shadows and reflections. Sisley always painted outside, even later in life when others painted in their studios. He effectively used broad roads or walkways across the paintings, giving movement and perspective.

Camille Pissarro

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), was born in Saint Thomas, West Indies, and moved to Paris as an adult to study art. Early in his career, he did a show in the Salon, and the Salon des Refuses. He moved into the countryside and began working with Monet, Renoir, and Sisley, adopting the Impressionist methods. Pissarro was the only one of the Impressionism artists to exhibit in all of the special shows. Later in his life, Pissarro had trouble with his eyes and stopped painting outdoors and stayed in his studio. Haystacks, Morning, Eragny (4.3.19) was painted in a meadow near Sisley's house in Eragny, the calmness in opposition to his city scenes. He painted other images of haystacks, similar to Monet's repetitive haystacks. In this painting, Pissarro sat in the afternoon light when the haystacks projected deep shadows as the brightly highlighted hay dried in the sun.

When Pissarro finally returned to Paris, he painted a series of the grand boulevards of Paris, some looking along the Boulevard Montmartre and others a view of Boulevard des Italiens. He stayed in a hotel with a view of the boulevards, people, carriages, and houses, inspiring him to capture the images he saw. The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning (4.3.20) was painted on an early gray day, the street filled with people hurrying to work. With a muted palette, he used the long stretch of housing to form the boundaries bordered by the wispy branches of the bare winter trees. The small dark patches formed the people and carriages traveling through the painting.

Mary Cassatt

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), born in America, first studied at the Academy of Arts in Pennsylvania before going to Paris to complete her training and travel through Europe, believing art education in America was inadequate. She successfully entered works into the Salon and was critically accepted. In 1877, Edgar Degas, who had seen Cassatt working in the Louvre copying old masters, captivated her talent. He invited her to become part of the set of artists called the Impressionists, the only American in the group. Degas became Cassatt's mentor as she changed her techniques, learning new ways to incorporate light and color, developing a specialty painting for women and children. She became a successful Impressionist painter and printmaker, only stopping in the last years of her life because of failing eyesight.

Images of women and children depicted in modern settings, well dressed and fashionable regardless of the activity, became the subject matter for Cassatt's work, a sense of femininity. In most of her paintings of women, Cassatt generally positioned the figure in a diagonal, starting in one upper corner and moving the figure to the reverse corner, stopping around the knees of the subject.

"Not only did she make her subjects women, and quite often, women who are not in the presence of men, … in control of their spaces, true to the social realities of the period but not subordinate to the unrealities of academic or allegorical painting."[4]

Afternoon tea was an important function for the women in the upper or upper-middle classes, part of their daily lives. Cassatt's sister, Lydia, and her mother also lived in Paris, and she used Lydia as a model in many of her paintings, including The Cup of Tea (4.3.21). Cassatt applied brushstrokes and color to form the shadows and shapes of the painting. The soft pinks and white present the feminine image contrasted against the dark stripes of the chair. The well-placed vase of flowers centers the eye; however, the darker blue of the vase blends into the same blue tones of the wall, the painting a balance of complementary colors.

Cassatt frequently used relatives in her paintings or different unrelated models as the two viewed in Young Mother Sewing (4.3.22). The child leans against her mother, who seems undisturbed, continuing her sewing. The girl gazes out at the viewer, displaying her boredom and desire to be somewhere else. The woman wears a well-defined striped dress set against the color outside the window and a green apron matching the grass. Stripes were a major theme Cassatt incorporated into her paintings. The vase of orange flowers compliments the softer green. The window opening and the park-like background are other motifs found in many of Cassatt's paintings. The woman who purchased the painting remarked, "Look at that little child that has just thrown herself against her mother's knee, regardless of the result and oblivious to the fact that she could disturb 'her mamma.' And she is quite right, she does not disturb her mother. Mamma simply draws back a bit and continues to sew."[5]

In the Loge (4.3.23) depicts a woman dressed for the opera, a popular pastime in Paris, and a place to see others and be seen by her peers. Entertainment venues like the theater or racetrack were popular activities for Parisians. Other Impressionists also painted attractive females at the opera, using the opportunity to paint scenes with multiple light styles, all reflecting in the spaces. Cassatt's figure was looking actively through the glasses across the audience instead of pointing her glasses downwards to the stage. A man in the upper part of the painting has turned his view towards her; she has attracted his attention for some reason.

Berthe Morisot

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), born in France, was fortunate to be supported by her family to pursue an art career; her grandfather was Jean-Honore Fragonard, a noted Rococo painter. She copied the old masters found in the Louvre and had one tutor who educated her in the standards of plein aire painting. Morisot developed an association with Edouard Manet and regularly sent work to the Salon. Critics defined her work as feminine because of the subject matter and delicacy of her work. She married Manet's brother, Eugene, and had one daughter who became a frequent model in her paintings. Morisot became friends with Degas, who encouraged her to work with other Impressionist artists and enter her work in their first show outside of the Salon. Often seen as a pioneer to be the first female exhibiting in the Impressionist show, such was her standing that Degas declared: "We think Berthe Morisot's name and talent are too important for us do without."[6]

The Cradle (4.3.24) depicts Morisot's sister sitting by the cradle with her daughter, Morisot's first portrayal of motherhood, a subject she frequently used in later paintings. The contemplative look on the mother's face, the positioning of her arms, and her soft expression all demonstrate a feeling of intimacy between a mother and child. Morisot uses her characteristic feathery brushstrokes of white and gray accented with pinks, blues, and lavender. Her first painting in the new Impressionist exhibit was not considered a critical success, only defined as elegant.

The Impressionists held eight shows of their work; Morisot exhibited Lady at Her Toilette (4.3.25) in the fifth show, a painting positively received by the critics. Morisot used soft, delicate brushstrokes, portraying intimacy with muted shades of pink, blue and lavender swirling around white and gray. The painting was thought to be erotic, an emotion frequently pursued by male artists and seldom approached by a female artist. Although the images in the painting are delicately developed, a sense of voyeurism is also created. The woman is unaware of the people viewing her in the mirror, a woman in the privacy of her bath.

Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\): Lady at Her Toilette (bwt 1875-1880, oil on canvas, 60.3 x 80.4 cm) Public Domain

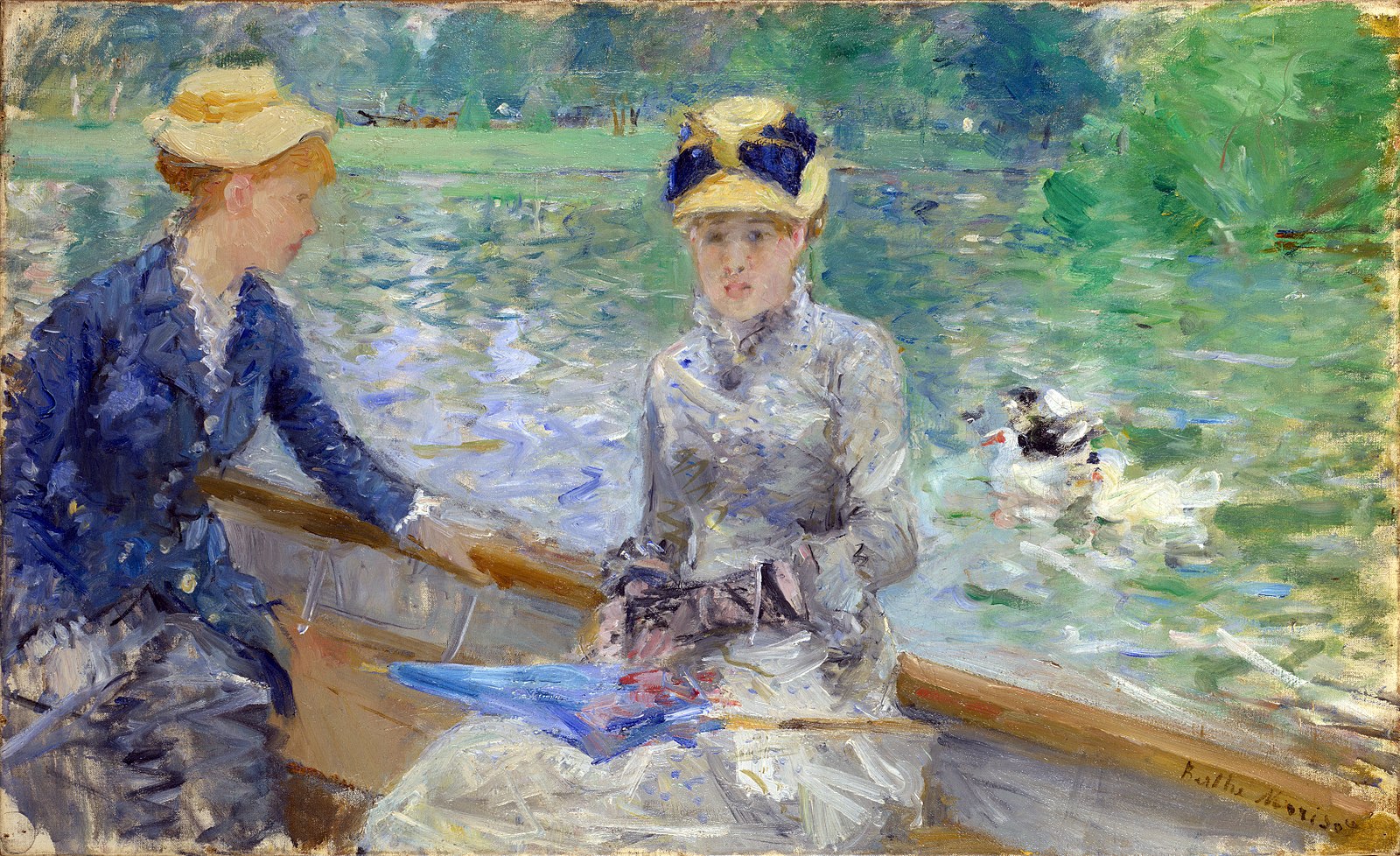

Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\): Lady at Her Toilette (bwt 1875-1880, oil on canvas, 60.3 x 80.4 cm) Public Domain Summer Day (4.3.26) portrays two women floating on the lake, each one looking in a different direction, contemplating their thoughts. It was acceptable for women to walk along a pathway or picnic in the park, and therefore, Morisot could set up her easel in this common location. She could not sit at an easel and paint the corner café or city streets as her male counterparts did. Morisot used her typical feathery strokes to capture the light on the water, the swimming swans, and the reflections of the plants on the bank. Critics of the time felt the work was too sloppy and unfinished.

The most striking feature of the principal painting stage is Morisot's unique and unmistakable brushwork, much commented upon by her contemporaries. Its repeated zigzags give a shimmering, restless quality to the image as if the entire scene were refracted through countless prisms. The effect of this is to unify everything into one continuous sweep of texture and colour: figures, background and water merge into a luminous blond tonality that ripples across the whole surface of the picture. Individual forms are almost submerged in the decorative patterning of the paint.[7]

Marie Bracquemond

Marie Bracquemond (1840-1916) was married to Felix Bracquemond, a lithographer who worked with many early Impressionist artists. Marie was a painter who followed the ideals of Impressionism, and some believe she created far more exciting paintings. Historians have noted the support their son gave to Marie and the jealousy of the father, Felix. Marie Bracquemond often acted as a recluse, and most of her paintings were created in her garden. Even though her husband disapproved of her art, she defended Impressionism throughout her lifetime, stating,

"Impressionism has produced…not only a new, but a very useful way of looking at things. It is as though all at once a window opens and the sun and air enter your house in torrents."[8]

The Artist's Son and Sister in the Garden at Sevres (4.3.27) is Bracquemond's son and sister, who was a standard model for her paintings. The white dress with highlights of blue and pink dotted with dark spots, spills everywhere, almost dominating the painting. The red blots of flowers form an encircling background to set off the figures, the son's white vest moving the eye from person to person.

Eva Gonzales

Born in Paris, Eva Gonzales (1849-1883) was educated in the artistic circles her father participated in and began training as an artist at age sixteen. She soon became a student of Manet and a model for many of the Impressionist artists. The basic style Gonzales learned under Manet remained the same throughout her life based on concepts from ordinary people and how they lived, frequently using her family members as models. Gonzales often worked with pastels to keep her colors and contours softer with a lighter palette. Although the reviewers of the Salon felt she demonstrated outstanding technical skills, her work was defined as a 'female technique.'. Gonzales died in childbirth when she was only thirty-four years old.

Jeanne, Gonzales's sister, is depicted in Morning Awakening (4.3.28), an early morning scene, not quite awake. The image defines a second in time, one of the standards of the Impressionists, along with using the effects of light shining through the window. The image was cropped, only the top part of her sister, bringing the viewer right into the bedroom scene. Gonzales used various blues, greys, and pastel pink and violet, all highlighting the white clothing and gossamer bedding and curtains.

Gustav Caillebotte

Gustav Caillebotte (1848-1894), born in France and fortunate to have a wealthy family, was educated as a lawyer before being drafted to fight in the Franco-Prussian war. After the war, he studied painting and became friends with some Impressionist artists creating new ideas about art, and he entered work in their second exhibition. Caillebotte painted with more realism than his contemporaries, although varying his style depending on each painting. He was interested in perspective and its effect on a scene, frequently cropping images or zooming close to a figure. The intersection in Caillebotte's Paris Street, Rainy Day (4.3.29), was near the train station; a look at the urbanization of Paris at the time, streets were redesigned and widened with the reconstruction of buildings. The people in the foreground, dressed in the latest fashion, were cropped near their knees, giving a strong perception of depth in the painting. He used gray tones to present the dreary, rainy day, the shiny cobbles of the street, and the dullness of the sky.

In the last half of the 19th century, France was alive with artists, and the Impressionists strengthened their position in history with the revolutionary new ideas and methods they developed. Painting plein aire or indoors to capture the luminance of light at a specific moment in time. They used shading and color to create lines, movement, and features with brushstrokes long or short, wide or narrow, illustrating social behavior, interactions, and personal life.

[1] Retrieved from http://giverny.org/gardens/fcm/visitgb.htm

[2] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437122?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=monet&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=12

[3] Retrieved from https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/works-in-focus/search/commentaire/commentaire_id/the-ballet-class-3098.html

[4] Retrieved from https://www.radford.edu/rbarris/Women%20and%20art/amerwom05/marycassatt.html

[5] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10425?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=Mary+Cassatt&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=11

[6] Spence, R. (2012, May 1). Berthe Morisot, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris. Financial Times.

Retrieved from https://colourlex.com/project/morisot-summers-day/

[7] Bomford D, Kirby J, Leighton, J., Roy A. (1990) Art in the Making: Impressionism. National Gallery Publications, London, pp. 176-181.

[8] Gaze, D. (2013). Concise Dictionary of Women Artists, Routledge, p. 206.