4.2: Realism (1848-1880)

- Page ID

- 120748

Introduction

During this period, revolutionary changes were happening throughout Europe, bringing an expansion of nationalism and the interest of state borders tempered by the interconnections of the industrial revolution. As the population increased and the cities grew, agricultural production expanded to support the food needs of the people, bringing an increase in the peasant labor and machinery needed to work the fields. Industrial manufacturing and distant trade markets required extensive labor in factories and demands for transportation systems to move raw materials and finished goods. Workers moved from small craft operations to laborers in large factories, an environment evolving into sweatshops. This was the time of the Victorian era, a time of strict discipline and morality, the advent of Darwinism and the theory of evolution, and the concept of an improved society through more democratic principles; free education for all, the vote by a secret ballot, legal trade unions, or a parliamentary form of government. Information was now available to all through cheap daily papers bringing the news to everyone.

Starting in France, Realism artists tried to paint objective views of life around them, frequently coarse and violent. After the French revolution, the people wanted democratic and representative changes in their lives and government; the Realists painted the life of the people around them, scenes of people working, peasants in the fields, life in the cafes, and naturalistic portrayals of the body. Artists were disillusioned trying to adhere to the artificial standards of the different salons and academies. Realism became the forerunner of the Impressionists, moving the standard away from the ideological and contrived works of Neoclassicism and Romanticism into depictions of real people. The dynamic brushstrokes, visible texture are essential in defining the painting. Realism did not mean painting with photographic reality; instead, Realism is determined by the subject matter, life as it happened to ordinary wealthy or poor citizens.

Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) believed he was the "proudest and most arrogant man in France."[1] His showing in the Salon was dramatically different from the prevailing Neoclassicism and Romanticism and completely unacceptable as artwork. Courbet ignored the standards of only painting mythical, biblical or historical works and was continually rejected until he opened the exhibition based on his interpretation of Realistic art. He was a very prolific artist; he painted women in multiple settings, cafes, ordinary people, and landscapes using bold brushstrokes and a palette knife to create his bold images. Some of his work was accepted by the Salon and others were completely condemned; however, he led a movement, inspired and taught others, bringing new concepts to the world of art and creating the momentum for the concept of the Impressionists.

Burial at Ornans (4.2.1), depicting the funeral held for his great-uncle, was a significant departure from the accepted Romanticism style and caused an uproar in the art world. Courbet said he just painted the people of the town; the priest, friends, choirboys, and family. Traditionally, the painting would focus on the deceased person, light shining straight from the heavens, perhaps angels, cherubs, or other religious entities. Many historians believe this painting was the end of Romanticism and the beginning of the new concepts of realistic and natural views.

Young Ladies of the Village (4.2.2) was the first in a series of paintings Courbet did portray women's lives. In this painting, the three women are walking near their village and appear to be giving money to the young boy who is herding cows. The young women were dressed in ordinary clothing backed by the scene of the meadow and cliffs. "When the work was exhibited in the Salon of 1852, critics bitterly attacked it, finding it tasteless and clumsy and berating the common features and countrified costumes…the 'ridiculous' little dog…the lack of traditional perspective and scale."[2]

Young Ladies Beside the Seine (4.2.3) was considered scandalous, a reaction Courbet loved. The women were not posed in approved positions; instead, they are lying on the ground, lacy undergarments visible, a seductive gaze, a man's hat in the boat, all very shocking. "…this painting, with all its richness of cloth and decoration, flowers and foliage, and its scarcity of bare flesh was perceived as more sexually disturbing than the nudes of conventional art."[3]

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Young Ladies Beside the Seine (1856, oil on canvas, 174 x 206 cm) Public Domain

Jean-Francois Millet

Jean-Francois Millet (1814-1875) was known for his paintings of peasants who were farmers. He was born on a farm and had to help with chores, building an understanding of how to plow, mow or harvest the crops. After training in Paris, his work was rejected by the Salon, and he turned to portraits to earn a living for his growing family. Millet found a supporter who encouraged him to change the subject matter, freeing him to pursue images of farm life. Millet liked to walk around the fields where he lived, observing local people in the fields. One theme he repeatedly painted was based on the concept of gleaning, the right of people to go to harvested fields and find small pieces of grain, generally done by older women or children. The sky in The Gleaners (4.2.4) is dreary, matching the tedious hard work to find bits of grain laying in the dirt. Poverty is reflected in the colorless clothing, fatigue seen in their hunched over backs, and the feeling emphasized by heavy layers of paint. Millet used the bent posture or lowered and hunched shoulders of his subjects to portray the hardships and poverty of people.

Edouard Manet

Edouard Manet (1832-1883) was supposed to become an officer in the navy; however, after failing the exams twice, he left for Paris to study art by copying paintings at the Louvre. Manet frequently submitted paintings to the Salon, as a way to become known to the public. The majority of paintings sent to the Salon by artists were usually rejected, and Napoleon III formed a new salon named Salon des Refuses. In this new venue, Manet exhibited his highly criticized and shocking painting Luncheon on the Grass. He was friends with many other artists in Paris, especially some of the newly famous Impressionists. Within a year of his death, his work was exhibited and ironically became acceptable. Many historians believe Manet to be the founder of modernism.

Luncheon on the Grass (4.2.5) portrayed a nude woman in the garden with two fully clothed men, the second woman in the background wading in the stream. The critics wanted to know what kind of debauchery was happening in this painting. Other, older artworks had depicted scenes of naked women; however, these women were in a modern setting, not goddesses or mythological, but maybe even prostitutes. Although the figures are grouped in the center of the painting, each one appears to be looking somewhere else, not interacting with each other. The nude looks at the viewer, smiling. The woman in the stream was looking down at the water, isolated from the others. This painting was Manet's refusal to follow the standards of his time, and many believe it set a new starting point for future art and its modernity.

Olympia (4.2.6) was considered another radical work; if the nude, reclining woman was a goddess or mythological representation, the image was appropriate; however, in Olympia, she was an ordinary person, not idealized, a prostitute, totally scandalous. The woman had common facial features, not the perfection of a goddess, and appears to be looking at the viewer, a daring concept. The maid is holding flowers, presumably from one of the clients, the black cat hidden in the background also staring at the viewer. Manet used bold brushstrokes, a technique considered unskilled by the standard of smooth finishes. His perspective is flattened across two planes, the bright, white body lying casually on the bed against the dark background.

Young Lady (4.2.7) is an image of a demure woman standing casually in her intimate dressing gown. The woman is the same nude model Manet used in Olympia and the Luncheon on the Grass. Recently, researchers have defined the painting as an "allegory of the five senses: the nosegay (smell), the orange (taste), the parrot-confidant (hearing), and the man's monocle she fingers (sight and touch).[4]

Rosa Bonheur

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), born in France, was one of the most well-known female artists of the nineteenth century. Her father was an artist and promoted art education for his children; all of Bonheur's siblings became artists. She did poorly in school, even failing her apprenticeship as a seamstress when she was only twelve. Art became her life, and animals were the subject matter she loved, sketching animals from books, models, and real life. She had many animals, visited zoos and slaughterhouses, and trampled through forests, learning to draw animals based on their realistic look, forms, and motion, not an idealized vision. She was an early feminist and frequently dressed as a man when she wanted to paint in public places. Bonheur had to obtain a license from the French government, one of a few women, to wear men's clothing. She traveled throughout Europe and America, painting animals and building her reputation, even receiving the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor.

Bonheur painted The Horse Fair (4.2.8) based on the frequent horse fairs held on the Boulevard de I'Hopital in Paris, a street lined with trees. Women were not allowed to sketch the horses, Bonheur dressed as a man, only attending twice a week to discourage attention. She captured the way the horses moved, the flow of their manes and tails, and the rippled muscles, all demonstrating her ability to capture the authentic look and feel of each horse. Deep in the shadows, people watched the horses, waiting for the show while the bright white horses move their eye around the painting.

Ploughing in Nevers (4.2.9) focuses on the oxen teams, their light-colored coats shining in the pale sunlight. The painting was a tribute to local agriculture and the difficulty of hands-on labor—the smooth muscles of the cows strain against the plow. The clods of roughly plowed dirt present a contrast across the painting, feeling the pull of the cattle and the exhortations of the herders. The image was a critical success of the time, a salute to the rural countryside instead of the corruption happening in the cities.

Winslow Homer

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) is one of the great painters of the nineteenth century from America. Beginning as a printmaker in Boston and New York, he created illustrations during the Civil War. After the war, Homer traveled in Europe, expanding his use of oil paint while simultaneously working with watercolors. He settled down in Maine along the coast in relative isolation, painting the ocean with its power and beauty. He depicted man's battle with the sea and the textures, look and feel of the seascapes created by the ocean's water. Breezing Up (4.2.10) was a painting Homer created in 1876, the centennial year of America, and the work was celebrated as a demonstration of the young country's spirit and hope. Most of the composition is focused on the left side of the painting, the sail pulling the eye off the edge. Light comes from the backside of the people, perhaps a reflection of the setting sun as the boys and man return, fish in the bottom of the boat.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg?revision=1)

The Maine Coast (4.2.11) portrays the power of the sea as Homer used thick white paint for some of the waves and smooth texture for others. The dark, blocky look of the rocks contrasts with the white waves, while the muted grays of the sky in the background add to the feel of the tumultuous ocean. One of Homer's biographers described the painting as; The design is of a rigid simplicity. We are looking seaward from the cliffs at Prouts Neck on a day of storm. At our feet the dark ledges are streaming with milky retreating foam, and just beyond them a monster wave raises its huge bulk as it comes shoreward with an exuberant look of tremendous power. Still further out to sea, in the gray mist, loom the oncoming lines of wave upon wave, until the horizon loses itself in a far turmoil of dimly seen billows.[5]

John Singer Sargent

Born in Italy, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) was descended from a well-known American colonial family. His parents went to Europe, where he was born while they were on tour, and remained in Europe. Initially, he was trained at an art academy in Florence before moving to Paris, the presumed premier location for students of the arts. Sargent traveled to the United States and Europe, painting portraits and local scenery, ignoring conventional posing and treatment. After the total rejection of his painting of Madame X, he went to London to establish himself as a portrait painter. Later, he moved between the United States and England, continuing to paint commissions and gaining a reputation for his watercolor paintings.

Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau as the painting was originally called) (4.2.12), was taken to Paris by her impoverished mother who arranged a marriage for her daughter with a successful banker. Madame Gautreau became a society figure, wearing lavender powder to maintain her pale appearance and drinking a version of arsenic to drain the color from her skin. Many artists wanted to paint her; Sargent, the up-and-coming artist, was appointed. Her low-cut dress and overly white skin contrasting with the black gown presented a scandalous image to critics who called it hideous, the look of a corpse. Sargent was humiliated and never painted a daring image, holding the painting for over thirty years before it was sold.

%252C_1883-84%252C_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.jpg?revision=1)

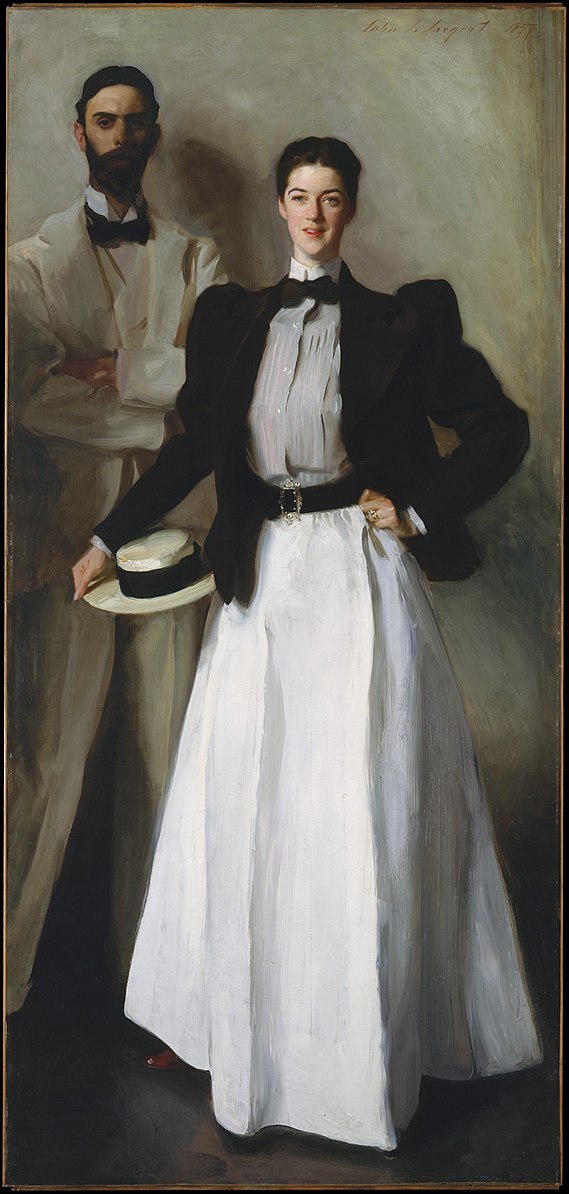

Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes (4.2.13) is a painting of the couple who originally commissioned the work with the image of Edith as a wedding gift for her husband. Edith planned to wear an evening dress as customary for a painting; instead, she wore everyday clothing. Her Great Dane was supposed to be standing next to her, one hand on the dog's head, however, the dog was not there, and her husband Isaac took the dog's place. It was unusual during this period for the man to be recessed in the portrait, dimly lit with shadows on his face, Edith firmly standing in the light, accented by the white skirt. Many critics thought it was inappropriate for him to be standing behind his wife; others attribute the pose to Stoke's respect for his wife's youthful energy.

Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), son of a woman born into slavery, was the first African-American enrolled in the Academy of Arts in Pennsylvania. The school was the first to move from reliance on plaster models to teaching the human figure to use live models, cadaver dissection, and anatomy classes. Although he was successful in school as an artist, he encountered racism and rejection, bringing him feelings of pain and torture. He married an opera singer who was white and experienced additional racism. Tanner went to Paris, where race was somewhat less of an issue, and studied the new Realism painters, an influence translated into his works. After painting several religious works, an art critic offered to pay Tanner to travel to the Middle East and study the places identified in Biblical stories. He lived in France most of his life, occasionally traveling to the United States. In France, he was selected as Chevalier for the Legion of Honor, an event he cherished as a high point in his career.

During a visit to the United States, he painted The Banjo Lesson (4.2.14), the image of an elderly man demonstrating to a young boy how to play the banjo. An African-American man playing the banjo was a typical image in American art; however, Tanner moved outside the typical stereotype and placed the two people in an intimate setting. He used light to enhance the intimacy, a natural blue-white glow from outside and the warmer illumination from the fireplace. The surroundings do not portray abject poverty frequently seen, only a humble home with plank flooring instead of dirt, plastered wall, and small pictures, the affectionate image of a man passing his skills to another generation.

Tanner concentrated on accurate depictions of the images in his paintings; his later works focused on religious themes, his most extensive body of work. His father was a minister, and Tanner probably was influenced by earlier teachings. His paintings brought realistic, precise work sharing the same space with looser areas through his emotional brushstrokes. He also focused on color and how the effects of different tones, hues, and colors changed the mood of the painting. He also moved between palettes of warm colors and cool colors, even developing the well-known "Tanner blues," a combination of turquoise and indigo. The Annunciation (4.2.15) demonstrates his use of warm colors, reds, and yellows, quieted with tans. Mary sits on the bed; her robes and blanket are exceptionally detailed. The angel appears as a yellow illusion, giving the intensity of a religious experience when the angel speaks to her.

Nicodemus and Jesus on a Rooftop (4.2.16) are painted in his palette of blues, a somber image. However, the use of light and shadows bring depth and emotion to the work, making the viewer feel included in the conversation between the two men. The wall and steps anchor the painting, a solid place while the background drops off into the valley's depth, with exceptional differences in height.

James McNeill Whistler

James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) was an American artist who lived in Russia, then primarily in England. He was always interested in art from an early age; however, after his father died, the family returned to America, and Whistler was sent to school to become a minister. He performed poorly and went to West Point, where he fought with authority and consistently received demerits, leading to his expulsion after three years. His mother finally sent him to Paris to study art, where he developed his two concepts; lines mattered more than color, and the fundamental and most basic color was black.

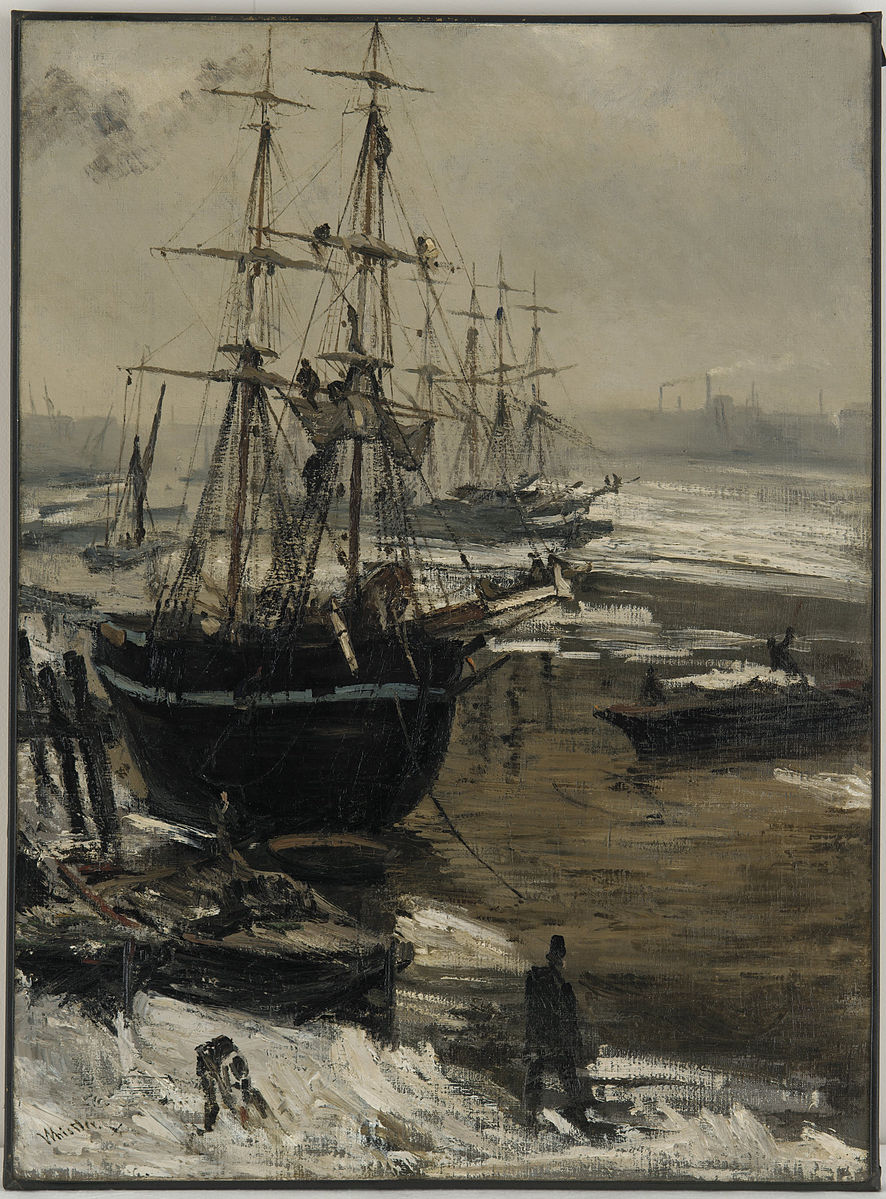

When Whistler moved to England, he worked on a set of paintings about the Thames River, the heartbeat of movement through London. He refined his limited palette, heavily based on black and the multiple tones it produced in the series. The Thames in Ice (4.2.17) is a view of the river in winter, the boats waiting for the ice to melt. The painting demonstrates his restricted palette, the dark boats floating against the white ice, the subtle shades of the two colors. He used heavy brushstrokes to balance the ice and water with thin, delicate lines of the ship's rigging.

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): The Thames in Ice (1860, oil on canvas, 74.6 x 55.3 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): The Thames in Ice (1860, oil on canvas, 74.6 x 55.3 cm) Public Domain When a model Whistler expected did not appear, he decided to paint his mother. Whistler's Mother (4.2.18) seems to be an austere composition, at first generating a negative response from the public, which was used to more colorful and vivid images. The palette is restricted and muted, her hands and face the most colorful elements. The curve of her body in profile is set against the rectangular look of the curtain and painting on the wall.

Anna Elizabeth Klumpke

Anna Elizabeth Klumpke (1856-1942) was born in San Francisco as one of eight children, her father a wealthy realtor. She fractured her leg when she was three and again at age five, and although her mother took her to Germany for treatment, she remained permanently handicapped. She studied art, copying the masters at a museum in Luxembourg before going to Paris. Her first work entered into the Salon won her a prize for the outstanding student, allowing her to continue to exhibit in the Salon. She admired and was inspired by the work of Rosa Bonheur and was determined to meet her. Klumpke set up a meeting with Bonheur by pretending she was an interpreter for the person interested in Bonheur's art. At the meeting, Bonheur was remarking about the talent and success of Klumpke and her sisters' talents concluding by saying, "I admire the American ideas as to women's education. The foolish prejudice that girls are exclusively destined for marriage does not exist in your country, as it does in mine. If I have been able to liberate myself from the prevailing national tradition, I feel I owe it to whatever talent heaven has bestowed upon me."[6]

Klumpke communicated by letters for ten years with Bonheur and finally wrote to her inquiring about painting her portrait, asking only for a few sittings. Bonheur responded and invited her to come and stay at her home to complete the painting. Although they were thirty-four years apart in age after they met they developed a close relationship and she moved in with Bonheur. They both entered into a formal contract about their personal and professional arrangements; Klumpke painted portraits of Bonheur and wrote her biography. Bonheur built a studio for Klumpke on her estate. After Bonheur died, her entire estate was left to Klumpke, who established the Bonheur museum and art school and wrote a book about her life together.

Klumpke continued to paint after Bonheur died and generally painted scenes or portraits of females. She painted three significant portraits of Bonheur as well as drawings and sketches. Rosa Bonheur (4.2.19) depicts a pose sitting in front of an easel, ready to paint; on her jacket, she pinned the medal Order of the Legion of Honor. She was 76 in the portrait and died a year later. The muted palette of grays and browns is offset by the bright silver-white color of Bonheur's hair, so finely rendered.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (4.2.20) was an early feminist, one of the organizers of the women's rights movement, focusing on the right of women to vote. This was the official portrait of Stanton to hang in the National Arts Gallery. Stanton had seen a portrait of Klumpke's mother and thought it well done, picking her to paint the official Stanton portrait. The colors are much like those done for Bonheur, each with white hair providing the contrast; a halo for the faces.

In the Wash-house (4.2.21) was exhibited at the Salon in Paris in 1888, and in 1898, Klumpke won the Temple Gold Medal at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts for the painting, the first female artist to win the award. The four young French women are gathered around the communal laundry, washing clothes and probably sharing the news and gossip of the day. The work was challenging, bent over with heavy wet clothes, the window providing light in the background. The dark foreground and clothing of the women contrast with the light in Klumpke's usual brown and gray tones.

Realistic painters wanted to capture the world around them, the natural environment of people performing everyday tasks. They still painted most of the artwork in their studios after sketching in the field. Manet advanced painting, not building up layers, instead of painting in a single session, scraping the paint from mistakes and repainting. The Realism painters began to use thick and broad brushstrokes to create highlights, shadows, and texture. The influence from the Realistic artists became the inspiration for Impressionism.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gust/hd_gust.htm

[2] Retrieved from https://www.gustave-courbet.com//young-women-from-the-village.jsp

[3] Retrieved from https://www.gustave-courbet.com//the-young-ladies-on-the-banks-of-the-seine.jsp

[4] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436964

[5] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11126?&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=winslow+homer&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=20

[6] Klumpke, A. (1940). Memoirs of an Artist, Wright & Potter Printing Co., p.30.