4.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 120747

Introduction

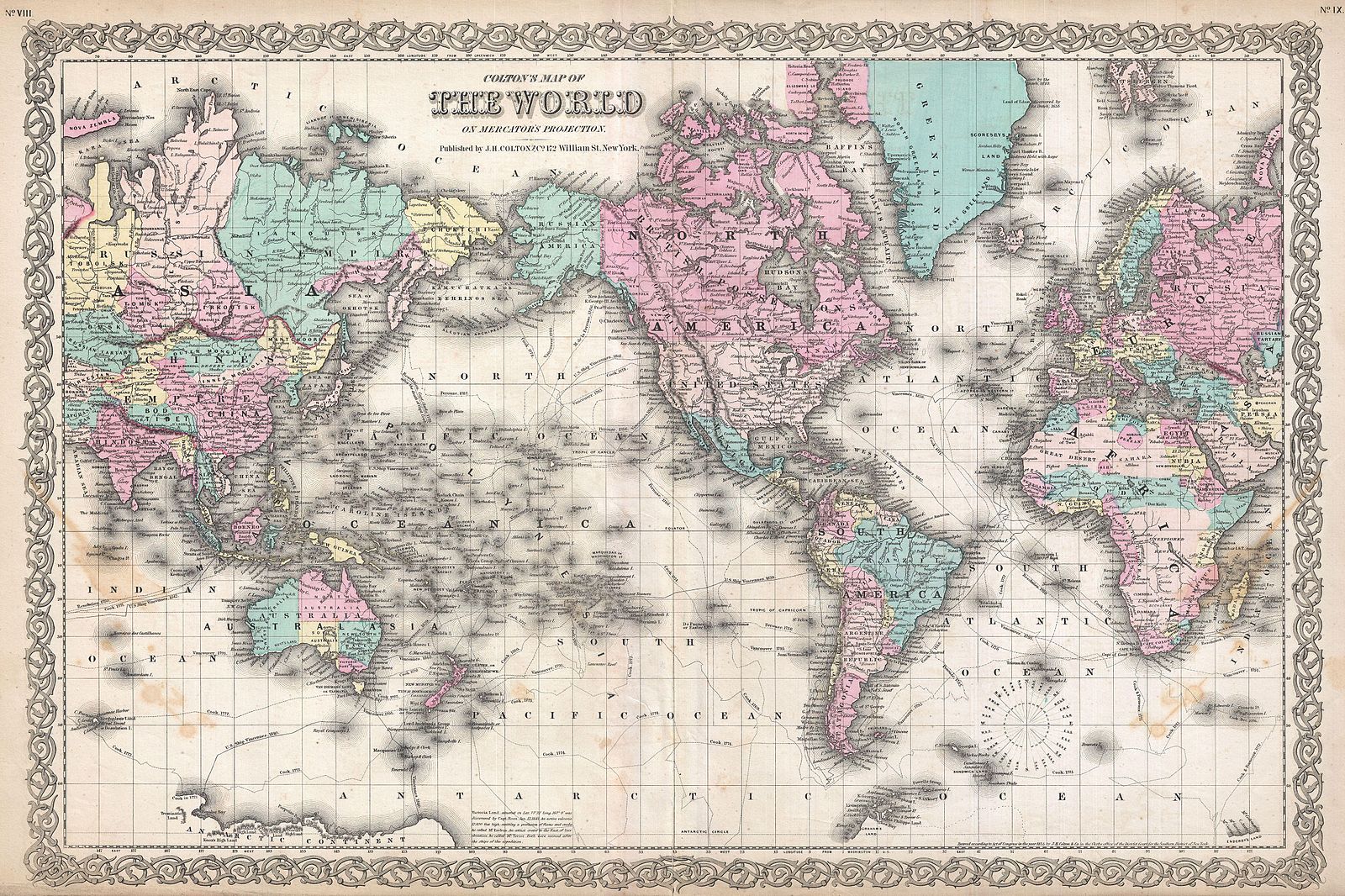

The 1855 Colton's Map of the World on Mercator's Projection (4.1.1) was positioned to focus on the Americas while incorporating the entire known world. Originally hand-colored in pastels and bordered with Colton's characteristic spiral motif, the map was a re-engraving. Colton also marked the routes of a few explorers, including Captain Cook. Antarctica is only partially defined, although a note on the bottom noted the recent discovery by Captain Ross of Mt. Terror and Mt. Erebus. Much of Africa was still designated as unexplored regions. The Mercator Projection became the standard methodology for map definitions after the late 1500s, when the concept was defined in 1569 by Gerardus Mercator. The 1500s was the age of exploration and traversing the oceans on the seas; the Mercator style of map embodied any straight line between destinations. However, the projection distorts the shape of the continents and their size.

By the 19th century, the continents were generally known, trade had expanded across the oceans, the balance of power had changed, settlers moved freely from one continent to another, and the industrial age fueled massive economic changes. Power also moved from royalty and the church to wealthy merchants and a burgeoning middle class. The century also endured multiple revolutions and wars, uprisings from slavery, or faraway rulers. Changes in art were evident in this period; technologies invented new products for artists, multiple movements developed and spread across the world, and artists traveled and learned new methodologies. In some contemporary art movements, the general art world became more accessible for female artists and artists of color.

Europe

In Europe at the beginning of the 19th century, France and Napoleon controlled most of the continent of Europe; his defeat brought significant changes to the countries. After the defeat, the Congress of Vienna, composed of representatives from each region met to redefine the borders of the continent's countries by changing the size of significant areas and balancing power in the desire to maintain peace. Prussia and Austria added territory, and Russia absorbed some of Poland, the neutrality of Switzerland was established, the Papal States were restored, among other realignments. Although there were different local wars, the basic structure of the agreements generally remained in place until World War One. With relative peace, the science and technology of the industrial revolution developed across Europe, and essential concepts developed; Darwin's natural selection, Pasteur's vaccine, theories of heat, energy, atoms, electrical transmission, the induction motor, and other significant contributions.

Europe changed significantly in the 19th century with the collapse of previous empires and kingdoms and the establishment of new power centers. The Russian Empire was geographically immense, extending from parts of Asia, Europe, and North America, third in the world in population with diverse languages, religions, and economic status. The government was based on a monarchy with primarily an agricultural economy and lagged behind Europe in the growth of industrial changes. The empire was also engaged in continual warfare in some parts of its territory, starting with the invasion of Napoleon, a disaster for Napoleon, uprisings within its borders, and wars with other European countries. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II did emancipate the serfs, ending the aristocracy's hold on land and power; however, the serfs now owned a small amount of land and had to pay excessive taxes, keeping them in poverty. By the end of the century, railroads extended trade, and agricultural growth helped improve the life of the peasantry while continuing to enhance the aristocracy. Social and political changes developed with multiple factions and views demanding reforms, sowing the seeds of revolution in the next century.

Although America won its independence from England earlier, in the 19th century, the British Empire was the world's powerhouse, overseeing and controlling extensive territory in Canada, South Africa, parts of Africa, different islands, Egypt, India, and ports in China. When the century ended, the empire exerted its control over a fifth of the world, including twenty-five percent of its population. After Napoleon was defeated in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo, the British did not have major rivals. The Royal Navy was able to exercise its control of the oceans for trade and supremacy. The navy was so powerful it stopped the slave trade and blocked most piracy. They integrated the entire empire into a global power based on a Pax Britannica (British Peace), establishing the empire as the world's arbitrator and controller of the territories. The British ideals of free markets helped spur the industrial revolution and economic growth, developing shipping lines and trading policies with steamships and linking the world with telegraph cables. However, by the end of the century, the old Ottoman Empire was crumbling, generating the Crimean War. The development and industrialization of Germany and the United States started the decline of British dominance.

As the economies in Europe transformed in the early 19th century to industrialization and revolutions altered the political status, poverty and desperation prevailed. Art moved from romantic portrayals to Realism, depicting the poverty of the people and their hardships. Industrialization also brought new inventions and methodologies, even benefiting the art community, making the materials of the artist portable, and improving printing procedures. Artists moved outdoors, and the naturalistic ideas of the Realistic transformed into the approaches of Impressionism using light, color, and brushstrokes in new and revolutionary methods. The Post-Impressionists expanded the concept of color and lines. The movements brought new ideas about how nudes were portrayed, what subject matter was painted and how emotions were expressed.

America

America was a fledgling and inexperienced nation at the onset of the 19th century. Expanding westward with the Louisiana Purchase started the movement of people out of the original coastal states and into the Midwestern regions. In 1820, approximately ten million people lived in the twenty-two states and territories; 1.5 million were slaves. There were eleven free states and ten slave states when the Missouri Compromise became law, bringing Missouri in as a slave state; however, no new slave states could be established west of the Mississippi River. Other new eastern states were admitted in pairs, one free and one slave, until 1850, when California became a state under the Compromise of 1850. California won its independence from Mexico in 1848; the gold rush in 1849 brought a surge in population, and the need for an organized government as the state was never a territory. As part of the agreement, the regions of Utah and New Mexico had no slave restrictions, and the Fugitive Slave Law was enacted; now, slaves who escaped to the free states had to be returned. The official institution of slavery remained solidly supported in the south from its beginnings until the end of the Civil War in 1865. With the addition of California, the United States existed from coast to coast.

Major industries developed and grew in the eastern half of the country before the civil war. The large rivers were a primary method of transportation aided by the invention of the steamboat. The telegraph opened up communication across the states, and the sewing machine created the tools for the mass manufacture of clothing. Most of the significant industrial factories were in the northern states. In contrast, the southern states focused on large agricultural plantations supported by slave labor, growing cotton for the mills of the north and tobacco for export. The railroads were one of the integral elements in the expansion of the United States. The railroads also helped accelerate the government's move to confiscate Native American territory. Native people were removed from their natural regions when the original colonists came. As America became an independent country, they moved large numbers of the tribes from eastern and Midwestern states further west. With the opening of the country's western half, the Native populations were again forced onto reservations in undesirable lands.

After the civil war, the transcontinental railroad fueled another industrial expansion, including steel manufacturing, the telephone, and the light bulb. The western states held vast mineral resources transported by the railroads. After the civil war, fourteen million people immigrated to the United States to work in factories by the end of the century. People's lives also changed; craft industries and small shops disappeared as men, women, and children went to work in the factories, a transformation from a rural country to urban centers. Factories were often dangerous and unsanitary places; people were forced into long hours at low pay, and the labor unions began to organize and grow. The industrial revolution helped propel America's growth and economic status, the internal destruction of Native Americans, ending formal slavery, and opening the lands to the world's immigrants, all within one century.

Early in the 1800s, artists were still influenced by European styles, painting portraits, and everyday life until the new ideas of American landscape painting were established and instilled with concepts of the new country and natural wonders, creating a new genre. Artists still went to Europe for training; American Realism painters embodied themes of democracy, heroic American life, and westward expansion instead of religious art or paintings of royalty. After the civil war and the opportunities to move throughout the country, photography, prints, and magazine illustrations became popular art expressions.

Color of Impressionism

Before the Impressionists, color was meant to be literal, the authentic color of the actual item in ordinary light. Color might be used from light to dark to develop shadows, folds, and light sources, as the object remains identifiable by its color; the sky is blue, and a cape is red. The Impressionists changed the concept of how color was used based on lighting or elements of nature as the wind blowing the grasses or the sun's position and effect, or weather conditions. The Impressionists sought out the conditions of nature and used multiple colors to create the right feeling and impact of the wide range of colors they found, painting en plein air.

Earlier artists usually painted a medium brown or rust color base on the canvas as a base or undercoat, building up to the actual colors. The Impressionists preferred a light-colored background, helping to strengthen the brighter paint colors to develop their light-saturated images. The favorite color of the Impressionists was white, a color mixed with others to create the bright light-reflective colors. They seldom used the darker earthy colors of previous painters, instead preferring the lighter side of the spectrum. The Impressionists also uniquely used complementary colors. Mixing complementary colors produces a dull mud color; however, they placed strokes of complementary colors next to each other, giving each color more intensity. The eye sees a single or local color and knows it is red or blue; however, when the local color is placed next to another color, the perception of the local color changes. That intensity was essential to achieve the luminous quality of their plein air paintings, capturing the influence of light from the sun, reflections on the water, or the movement of leaves at a point in time. They discovered the two-color were detectable up-close yet farther away; the combination looked as brilliant as the original color.

Color of Post-Impressionism

The Post-Impressionists moved from the luminescent quality of paint and light to a color palette of artificial colors and dynamic presentations. Their palette was based on saturated hues of a broad range of imaginative or unreal colors, stressing artificiality. They used intense and seemingly random colors as a symbolic definition of emotions. The vibrant colors were frequently expressed with geometric planes, distorted forms, and more diffused light. The Post-Impressionists were motivated by Asian art, especially the unique woodblock prints, and captured their essence by flattening the geometric planes in their work.

Although the Impressionists used visible brushstrokes to accentuate color changes and movement, the Post-Impressionist went further using broad strokes, sometimes flowing across the scene and other times thick and bold. The type of brushstroke helped create the emotion and feel of the image. They used color and line to depict the image and emotion by symbolic expressions, and although the result may appear distorted, the object had an expressive truth.

Landscapes in North America

Although landscapes had long been a subject of art in Asia, it was not an acceptable genre in the European or American tradition until the 1800s. The genre was ignored because landscape painting was not part of any classical or mythological stories and did not include any human anatomy. John Constable, the English painter, started painting the region around his house in the early 1800s, developing the standard for landscapes and an influence on the American landscape painters. As America began to develop westward, artists traveled with the explorers. The breathtaking vistas inspired them they found as they moved further westward, generating a new-style free from European influence.

The composition of the landscape painting was essential; the depth and distance of the horizon, the hazy mountains in the far background, the foreground including a detailed tree or large boulders with deep cracks. Artists also changed some of the elements and might add a small person to demonstrate a person's relationship to the grand, vast landscape. Their encounters led the artists to paint monumental images, light, and luminosity, an essential element of how the sun reflected off the water or created shadows in the trees. Instead, they could not make light; they camped in a location waiting to capture the same light. Whether the sun overhead, a storm on the horizon, or the deep shadows of the sun setting, the light was an important quality and required perseverance to obtain the perfect composition. Color has also developed relationships throughout the paintings. The color of the mountains-- a hazy purple or snowcapped gray-white, how the canyons presented erosion-- yellow-brown cliffs or green and rolling, colors of the sky, shadows, or trees; the color of the elements in the painting created the mood and unlimited vastness of the work. Landscape paintings were an important part of American history, the struggle to destroy nature, and the future of modern environmentalism.