3.2: Akan and Kuba (1700 – 1900)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Introduction

The Akan were composed of different chiefdoms, loosely associated within an overall confederation, who lived in the area of the current country of Ghana. The area encompassed great forests and natural resources; the people recognized their rich culture and artistic traditions, especially wood and gold. Each group was ruled by a chief and a hierarchy of organizations below the chiefs, frequently linked to family groupings for generations.

Because of its influential role, the chief's court has exerted a magnetic pull on craftspeople, …attracting some of the best skilled artists and artisans. This has resulted in a critical mass of creative talents. The Akan consider art associated with the courts to be communally owned property. [1]

Art was therefore valued, especially when a ruler wore it. Each chief possessed a stool, jewelry, headgear, shoes, and textiles. The rank and prestige of the chief were reflected in how elaborate and valuable the different materials were and the quality of the artwork. By the middle of the 18th century, the different chiefdoms organized into a larger centralized government, expanding into other territories. From the 1450s, when the Portuguese established trading ports with the region, European intrusion grew, continually developing alliances, building forts, and eventually shifting the Akan chiefdoms from gold as the major financial export to exporting slaves.

The Kuba came to the area currently called the Democratic Republic of Congo in central Africa during the 16th century, living in relative isolation until the late 1800s when the Europeans came. Initially, they were an assemblage of multiple chiefdoms until they were unified under one king. The Kuba people were ambitious, constantly aware of their status and how to display their position and wealth to others through art. They supported specialized carvers, weavers, and others to create artworks portraying their status.

Akan Gold

The attraction of gold is unlike any other mineral because of the perceived value from even early times; a valuable commodity from the beauty it adds to ornamentation or significance as currency. Located in the current country of Ghana, gold mining has been an essential industry for several centuries. When the Portuguese came to the region in 1471, gold mining was a standard industry; gold was found in streams between the hills. Gold washed down from the hills to the estuaries along the coast in the rainy season, where people panned for gold after each heavy rain. Gold was also found at the base of waterfalls. Young boys dove under the water and scooped the sediment from the bottom. The research found the most effective way to reach the gold was for "women and boys to scoop holes in the alluvial earth or gravel on the river banks or in whirlpools on the shallow sides."[2] Generally, panning for gold was done by family groups of women and young boys, and occasionally, older males. The work was laborious, requiring repeated washings, shaking, and examining the debris in the trays they used to find the small nuggets of gold.

However, large deposits of gold were hidden in the mountainous areas, the origin of the fragments washing down the rivers. Discoveries of the large veins of gold were accidental at first; nevertheless, people in the area learned to follow a particular type of plant or the colors of the soil to lead them to veins of gold. When a vein was discovered, they dug shallow holes from three to six feet deep, finding a large deposit of gold hidden under the layers of gravel and clay. Short tunnels were dug and supported with bamboo and local wood; however, these were finite shafts, abandoned when they became too deep or flooded. Today, much of the gold is mined with high-tech, scientific methods, although the small, family-based mining process still is in place.

Gold was the trading commodity for the Akan and a significant representation for the kings, a symbol of status and ornamentation. "Aside from bringing enormous wealth to the Akan kingdoms through trade, gold was considered the earthly counterpart to the sun and an incarnation of kra, or life force, and was incorporated into a wide spectrum of courtly paraphernalia."[3] To standardize the measurements for gold, the Akan made weights cast from brass in all types of decorative designs. The unique forms of the Akan weights portrayed humans, animals, plants, objects, or just geometric shapes and represented ordinary activities and elements of life. The brass weights were only as large as a few centimeters and scaled to the Islamic ounce. Each weight is based on a designated amount for the traders and merchants establishing a standard method to weigh gold, the currency of the time. About 300,000 figurative weights survived from an estimated total of 3,000,000.[4] The first weight (3.2.1) was decorated with geometric lines, perhaps representing someone's name or a word.

Figure 3.2.1: Gold weight: Geometric (18th century, brass, .08 x 2.9 x 3.2 cm) Public Domain

Figure 3.2.1: Gold weight: Geometric (18th century, brass, .08 x 2.9 x 3.2 cm) Public DomainThe seated male (3.2.2) was harder to cast, tiny in size with well-defined features.

Figure 3.2.2: Gold weight: Seated Male (18th century, brass, 2.5 x 3,1 cm) Public Domain

Figure 3.2.2: Gold weight: Seated Male (18th century, brass, 2.5 x 3,1 cm) Public Domain The mudfish (3.2.3) is encircled with small lines of geometric designs. A man often gave a complete set of weights for a wedding present, supporting his becoming a merchant or trader.

Figure 3.2.3: Gold weight: Mudfish (18th century, brass, 4.5 cm) Public Domain

Figure 3.2.3: Gold weight: Mudfish (18th century, brass, 4.5 cm) Public Domain

The Akan people did not have a history of written traditions, and knowledge was passed through oral stories and sayings recited by the local leaders and conveyed to the people. The court counselors and historians were honored people and carried a staff representing their office and expertise. The staff (3.2.4), made from wood and covered in gold foil, has two figures on either side of the spider web and spider, a reference to their saying, "No one goes to the house of the spider Ananse to teach him wisdom," Ananse was the spider who originated folk tales and was linked to linguists.

Akan Ruler's Art

The most prized possession of the chief was his seat, a sign of leadership and the central position of his political life. After a chief's death, 'the stool has fallen' was associated with his demise, and the next leader took his place when he touched the stool. The ceremonial seat or stool (3.2.5) on a raised platform is curved and supported by four legs and an ornate column in the middle. The stool is all carved from one piece of timber and decorated with incised designs and inlaid metal. The unusual five-legged form is referred to as kontonkrowie, or "the circular rainbow" based on the Akan proverb "the rainbow is around the neck of every nation," calling to mind the king's role in uniting and controlling the kingdom.[5]

The statues of a ruler (3.2.6) were representative of the regalia important to the office. The appearance was essential, and the figure appears to have a robust figure indicating good health. He wears a headband, probably faced with gilded squares of wood, and a necklace that would have been made from cast gold. Sitting on his five-legged stool, he held the curved sword with gold gilding, representing the importance of his office. On his feet are the crucial sandals; once he became a chief, his feet were not supposed to walk on the ground, or sickness and famine would occur throughout the region. Made from wood, the artist used white kaolin to coat the sculpture indicating spiritual devotion.

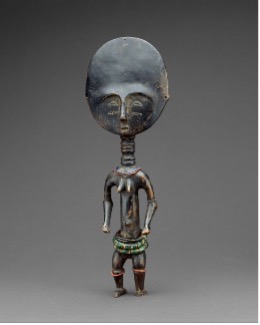

After being blessed by a religious leader, the akua ba was carried by a woman who wanted a child. The flattened, round head symbolized beauty and rings around the neck represented fat rolls, a common theme demonstrating health and prosperity. The mouth on a figure was small and delicate and set low on the face. The details of the sculpture were varied; the most common style is seen in Akua ba 1 (3.2.7), more abstract, with horizontal arms, the torso shaped like a cylinder, and small suggestions of a naval and breasts.

Akua ba 2 (3.2.8) is rarer; the body has more significant arms and legs yet still follows the akua ba style. The small statues were kept as family treasures and beautiful representations of a loved child.

Akan Textiles

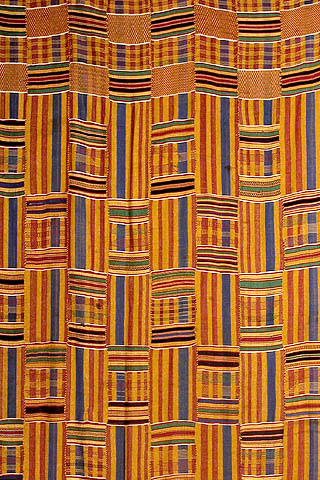

The textile arts were highly developed, and kente cloth, woven material of multiple designs and colors, had specific meanings for the Akan people. Legends say the spider Ananse was spinning his web, and the people wanted to recreate the beauty of the web. The early cloth was made of cotton and colored with dye made from a local tree. Each square on the fabric was woven with different designs, each design holding a special significance. It was commonly believed that a woman's menstrual cycle interfered with the weaving of the cloth, so the fabric was only woven into textiles by men (3.2.9).

Kente cloth (3.2.10) developed into a vibrant, colorful textile filled with symbols and color to represent different proverbs, embedding the cultural mores into the cloth and the people's relationship with their ancestors.

Kuba Figures

The art of the Kuba was very sophisticated and an essential part of the culture, the most well-known type of artwork are ndops, images of royal figures. The figures were carved from hardwood, covered with palm oil, and measured from 48 to 55 centimeters high. The carver used a small ax and knives to create the statue, sculpted to represent the actual features of the king. The importance of the ndops was reflected in the belief that whatever happened to the ruler would also happen to the ndop figure. Following tradition, the ndop (3.2.11) portrayed the king sitting on a pedestal with his legs crossed, his left hand holding a dagger, the right hand resting on his knee, his headdress a decorated board. Each of the ndop sculptures was identified to a specific royal and might include some of his particular objects as part of the statue; the small drum decorated with geometric designs and a severed hand, the bracelets, belt, and headdress reflecting his royal status, and his personal ibol or emblem on the base. The figure was also associated with the king's fertility, and the figure was kept in the women's living quarters. When one of the king's wives was having a child, the figure was placed next to her, safeguarding a good delivery.

.jpg?revision=1)

The different subgroups in Kuba society all had their own internal and important hierarchy status, forming an elite class within each community. An alcoholic drink, tasting both sweet and sour, was the favorite beverage for men of high positions. The drink was made from the raffia palm trees, which provided multiple materials for artwork and a relaxing brew. The status people wanted to ensure others knew their position and used custom prestige vessels made by master sculptors to imbibe the palm wine. The vessels were generally skeumorphic, a realistic version of another image, frequently depicting something about the owner's occupation or possessions.

Kuba Drums

Drums were standard in Kuba society, often connected to royalty and used for rituals and festivals. The drum-shaped drinking vessel (3.2.12) stands on four arched legs and one central leg in the center. The handle is shaped like a hand with a mask on top; the fingers face outwards, precisely carved with appropriate ridges. The wooden vessel is carved with lines and zigzags, following a pattern found in baskets and textiles.

The breasted drum (3.2.13) depicts a perfectly formed vessel with two breasts out of wood with a leather top. The drum is held in place with sticks embedded into the sides at a 45-degree angle and rope is used to secure it in place. Drums were an important part of Kuba cultures and were used for music, dancing, and ceremonial purposes.

Kuba Lakets

Kuba men also wore hats to display their position and leadership. The laket or hat was small, shaped like a dome, and ranging from simple to ornate. All of the hats were made from raffia fibers in the coiled style of making a basket. Inserted on the crown of a man's head, a hat pin was inserted from the front to the back of the hat to hold it in place. Some of the hats were plain without ornamentation, and the raffia formed in some sort of pattern. If the person had a special status, the hat might be decorated with cowrie shells (3.2.14).

A high-level person wore a laket (3.2.15) embellished with the cowrie shells, glass beads, and oversewn with rows of raffia thread.

The ruler demonstrated his status with an elite hat (3.2.16) embellished with elaborate shell and bead ornamentation.

Kuba Boxes

The Kuba artists made carved ornate wooden boxes or containers to hold personal items or tukula powder made from the red heartwood of a tree and ground into a powder for dyes, paints, or cosmetics. Red color represented beauty, and the powder was made into a paste to decorate the face and chest for ceremonies. The surface of the boxes was carved in low relief enhanced with symbolic and geometric patterns. The first container (3.2.16) has four sections divided by raised bands of zigzagging lines and a diamond pattern based on the tangled vines growing in the area and shaped comparably to baskets with a cylindrical body and square bottom.

Figure 3.2.17: Lidded Vessel (19th century, wood, camwood, palm oil, 26 x 19.1 x 19.1 cm) Public Domain

Figure 3.2.17: Lidded Vessel (19th century, wood, camwood, palm oil, 26 x 19.1 x 19.1 cm) Public Domain The crescent or the half-moon-shaped box (3.2.17) also is elaborately carved from wood, demonstrating the wide variety of shapes and styles of these boxes.

Kuba Masks

The Kuba specialized in mask making and had over twenty varieties, each one created with specific meanings and uses, especially during celebrations and masquerades with dances. The helmet style was the most common, highly textured, and decorated with various materials, including shells, beads, feathers, raffia, or animal fur. One of the important masks was for mwashamboy (3.2.19), representing Woot, a cultural hero. The mask made of animal skin with wooden eyes, nose, and ears had added ornamentation with shells, beads, and cowries. The eyes are affixed to the outside of the mask without any viewing holes, so the dances were relatively slow. An elaborate mask like this one might be the king's mask, although worn by the chosen dancer, not the king himself.

Figure 3.2.19: Helmet mask (mwaashamboy) (19th century, cotton, leather, shells, beads, wood, string, bone, raffia, pigments, 52.1 x 27.6 x 39 cm) Public Domain

Figure 3.2.19: Helmet mask (mwaashamboy) (19th century, cotton, leather, shells, beads, wood, string, bone, raffia, pigments, 52.1 x 27.6 x 39 cm) Public DomainThe character bwoom was believed to be a prince or a commoner depending on interpretation and a mask standard for masquerades. A mask for bwoom (3.2.20) always had a protruding forehead and accented nose and was found frequently at funerals, an important secondary use for the mask. The mask was embellished with a specific pattern of beads to give meaning to the mask.

Kuba Textiles

Kuba textiles were woven from pieces of palm leaves or palm raffia and enhanced with elaborate geometric embroidered patterns giving the textile depth and the appearance of smooth velvet (3.2.21). Men used the palm raffia to weave the cloth on small looms forming a basic cloth for the foundation of any design. Because the raffia created a very coarse fabric, the woven piece had to be pounded to soften the texture and feel, ready for the female members of the clan to complete the cloth. They used twool, a dark red material from one of the tropical trees growing in the region, to create the dye. Using needles and raffia strands, the women embroidered different geometric designs, lines, and textures.

The Akan people have a rich set of creative traditions fostered by the king and royalty. Art was part of their visual and verbal customs helping to bring prosperity to the area and a strong sense of identity. The kings were responsible for supporting artistic innovation through new ideas, balanced by tradition and the resourcefulness of the artists' use of natural resources for the Kuba people. Artworks in both areas were an integral part of the people's lives, and the artists formed an important part of their societies.

[1] Quarcoopome, N. (1997). Art of the Akan. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 23(2), 135-197.

[2] Ofosu-Mensah Ababio, Emmanuel. (2011). Historical overview of traditional and modern gold mining in Ghana. International Research Journal of Library, Information and Archival Studies. 1. 6.

[3] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/317680?searchField=All&sortBy=relevance&ft=akan&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=24

[4] Vansina, J (2014). Art History in Africa: An Introduction to Method, Routledge, p. 201.

[5] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/314978?searchField=All&sortBy=relevance&ft=akan&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=27