3.5: Ukiyo-e (1636 - 1911)

- Page ID

- 120744

Introduction

In 1615, the Tokugawa clan consolidated their power in Japan. It moved the central government to Edo (modern Tokyo), the Edo period (also known as the Tokugawa period), and relative peace for the next 250 years. In contrast to the previous Momoyama period, the Tokugawa shogunate maintained stability, allowing for sustained prosperity based on an agrarian economy.

Prosperity and stability led to the growth of cities and sophisticated urban culture with a thirst for diversions from the mundane.

Theaters, tea houses, bars, and brothels were diversions for the popular cultures of the era. For taxation and control, the shogunate confined these activities within a few blocks in the city to an area known as the pleasure quarters. Cities such as Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka developed pleasure quarters, the centers of popular entertainment. The participants of Edo popular cultures were chōnin (townspeople), comprised primarily of merchants and artisans.[1]

In the hierarchy of Tokugawa society, merchants occupied the lowest rung, while samurais occupied the highest. Ironically, the merchant class gained the most financial power. Sumptuary laws and rigid stratification meant chōnin were unable to improve their social standing despite their education, skills, and wealth. As a result, they spent their leisure time and disposable income in literary and artistic pursuits while indulging in the pleasure quarter: theater, women, food, drinks, dancing, music, and sightseeing. These activities led to the rise of arts and cultures of the commoners (the middle class) as an alternative to the arts that high-ranking samurais patronized. The pictorial expression reflected this world of popular entertainment in these urban centers known as ukiyo-e.

“Ukiyo” (浮世) means the “floating world” while “e” (絵) means “picture(s).” The idea of the “floating world” is related to an older Buddhist concept of melancholia from the impermanence of human life on earth. Both concepts highlighted the fleeting, untethered existence where nothing lasted – fashion, beauty, seasons, a night of passion. The entertainment world of the pleasure quarter thrived on novelty and ever-changing trends. In the Edo period, the term “floating” emphasized savoring the present moment in a carefree realm, forgetting the mundane constraints of everyday life. Pictures of the floating world – ukiyo-e -- were visual records of the activities of the chōnin and the people who worked to entertain them.

Hishikawa Moronobu

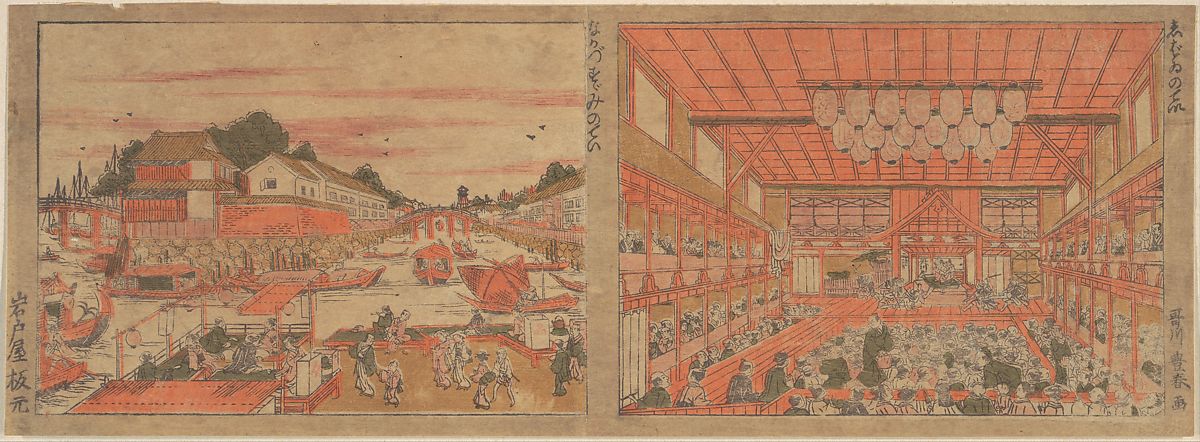

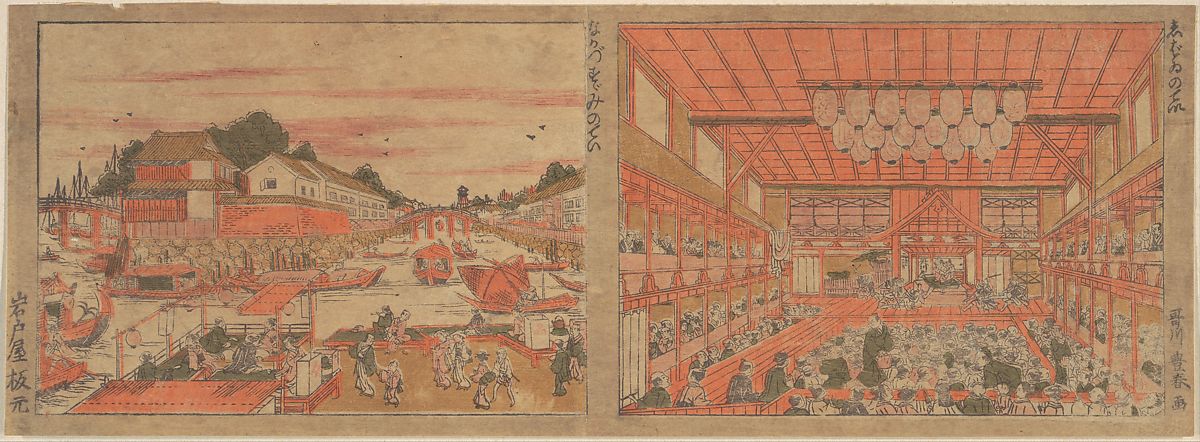

The series The Appearance of Yoshiwara (3.5.1) by Hishikawa Moronobu (1618-1694) shows a brothel interior. (Yoshiwara was the pleasure quarter of Edo). The patrons sat down towards the right, just in front of a tree. They enjoyed a dance by a courtesan while musicians accompanied her with samisens and a drum; attendants on the side waited, and served food and drinks. In addition to genre scenes of the pleasure quarters, subject matters of ukiyo-e include beautiful women (often courtesans), kabuki actors, scenes in kabuki plays, erotica, ghost stories, and folk tales. In the 19th century, as domestic travel and tourism increased, landscapes (images of beautiful places) also became popular.

Although the term “ukiyo-e” today is synonymous with Japanese woodblock prints from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, representations of the floating world first appeared in paintings in the early seventeenth century. Since paintings could not keep up with the insatiable demands for such images, woodblock prints became the primary medium for ukiyo-e starting in the second half of the seventeenth century. With woodblock printing, multiple editions of the same image were inexpensively reproduced to satisfy the masses. Japanese woodblock printing was essentially a collaborative process between a publisher, an artist/designer, a block carver, and a printer. The artists drew or painted an image in consultation with the publisher, who determined whether mass production of the image would be profitable. The publisher also gathered the funds and set up all personnel involved in the production of the prints. The block carver transferred the artist’s drawing onto a block of wood (typically cherry wood), and the printer applied the dyes to the printing surface and created the print. Unfortunately, the names of the last two professionals were not recorded for posterity; the print only stated the name of the publisher and the artist. The names discussed here are the names of the artists/designer of the prints.[2]

Suzuki Harunobu

Initially, prints were only black and white, as seen in Hishikawa Moronobu’s print above. As printing techniques evolved, polychrome prints appeared in the middle of the eighteenth century. The influence of chōnin in this development cannot be understated; Suzuki Harunobu (1724-1770) created the first multicolored calendar in 1764 under the private commission of a group of wealthy upper-class chōnin and samurai. With the financial support from his patrons, he experimented with color dyes, woods, and printing techniques to achieve a print with ten colors. Such a print was unheard of at the time, but it quickly became the inspiration for other artists and publishers.

Harunobu mainly represented beautiful women or women with their paramours. Both males and females have slight figures; the outdoor settings are sparse yet idyllic. Lovers Walking in the Snow (3.5.2) portrays a romantic scene of two people sharing a large umbrella as they walked in the snow. The contrast between the man’s black attire and the pale snow centers the composition. The man turns solicitously towards his companion as she demurely looks down and leans her head towards him. This subtlety and lyricism make Harunobu’s prints so appealing.

Night Rain at the Double-Shelf Stand (3.5.3) shows a simple yet delightful indoor scene; a young lady falling asleep in front of a water boiler set on a double-shelf stand when a mischievous boy attempts to insert something in her hair. Harunobu’s detailed rendering of furniture, tea utensils, room partition, and windows gives his viewers s a glimpse of the interior of a Japanese house in this period.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Night Rain at the Double-Shelf Stand (ca. 1766, woodblock print, ink, and colors on paper, 28.6 x 20.3 cm) Public Domain

Torii Kiyonaga

Images of beautiful women is a category in ukiyo-e knowns as bijinga. The subject was mainly courtesans of the pleasure quarters, although some artists also represented local beauties outside the red-light district. In some ways, Harunobu popularized this category by rendering lithe frames in colorful outfits and tranquil backgrounds. Another artist considered the next master in this category is Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815). In contrast to Harunobu’s slender figures, Kiyonaga’s women are tall and statuesque; they fill their space with grace and confidence. Kiyonaga also dealt with complex compositions by having more than two characters in a diptych or a triptych.

Enjoying the Evening Cool on the Banks of the Sumida River (3.5.4) is a diptych; however, each image can exist independently without the other. The left image depicts three women enjoying the breeze by the river while sitting and standing by a bench. The seated lady in the darkest outfit is the most captivating as she takes in her surroundings -- the breeze and the view -- with joyful abandon. She pushes her face and her torso forward, demonstrating her keenness; Kiyonaga further accentuated her, providing an unmistakable silhouette of her profile against the negative white space. Following her gaze and posture, viewers can see a row of houses across the river, adding depth and an overall riverine atmosphere to the image.

Kitagawa Utamaro

Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806) added another level of excitement to the bijinga category by depicting beautiful women close-ups, showing their heads and torsos only. Hanamurasaki of the Tamaya, (3.5.5) from the series Seven Komachi of the Pleasure Quarters is an example of this format. Utamaro captured the celebrated courtesan Hanamurasaki poised with her brush, wetting it on her lips just before she was about to write her letters. The close-up format gives the artist ample opportunity to lavish details on the elaborate coiffure of the courtesan and the exquisite patterns of her kimono.

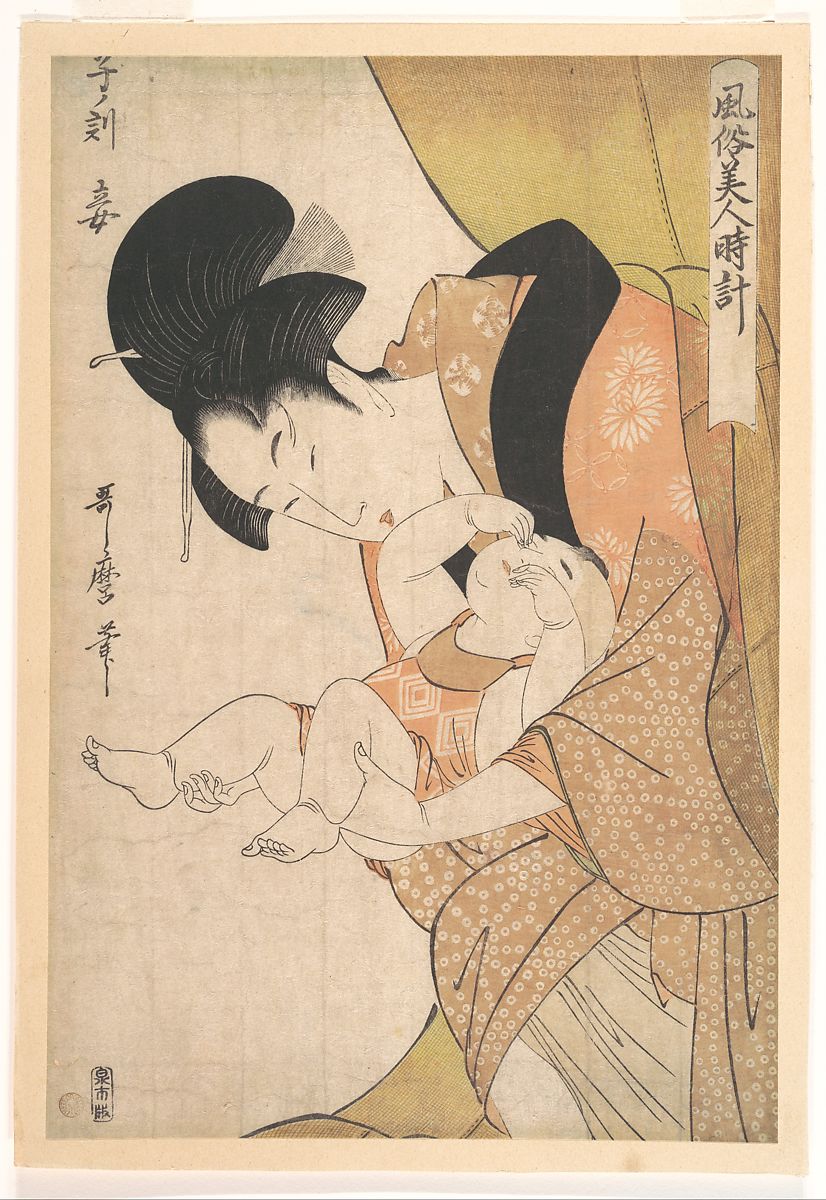

Utamaro’s primary interests were not in patterns and decorations; he was interested in depicting the many daily activities of Edo period women. For example, an intimate portrayal of motherhood can be seen in Midnight: Mother and Sleepy Child (3.5.6) from the series Customs of Beauties Around the Clock. Other activities portrayed include women doing their hair and make-up, reading books and letters, observing insects, or watching themselves in a mirror. Utamaro’s keen eyes and genuine interest made him the foremost artist in representing Edo’s beauties.

Kabuki was -- and still is -- an exciting performance; actors’ gestures and expressions are exaggerated, and stages have trapdoors and rotating mechanisms to facilitate a dramatic entry and swift character transformation. Interior of a Kabuki theater (3.5.8) demonstrates the details of the theater.

Kabuki theater and the woodblock printing industry were interdependent. The theater industry relied on inexpensive printed brochures, playbills, and posters to promote their plays. At the same time, Kabuki actors provided the subject matter for yakusha-e (actor prints), a source of creativity and income for the ukiyo-e industry. Actor prints were similar to posters of movie stars today; adoring fans purchased and collected them. Efficiency in printing and competition among publishers kept the price low enough for everybody to own a print at the cost of a bowl of noodles. Ichikawa Danjūrō V as Hannya no Gorō in Shibaraku (3.5.7) was an advertisement for the theater.

Katsukawa Shunsho

Katsukawa Shunsho (1726 -1793) was known as a prominent artist from a well-known school, and he studied with two famous ukiyo-e artists. Shunsho was celebrated for his depictions of Kabuki theatre actors. Kabuki was -- and still is -- an exciting performance; actors' gestures and expressions are exaggerated, and stages have trapdoors and rotating mechanisms to facilitate a dramatic entry and swift character transformation. Interior of a Kabuki theater (x.x) demonstrates the details of the theater. Kabuki theater and the woodblock printing industry were interdependent. The theater industry relied on inexpensive printed brochures, playbills, and posters to promote their plays. At the same time, Kabuki actors provided the subject matter for yakusha-e(actor prints), a source of creativity and income for the ukiyo-e industry. Actor prints were similar to posters of movie stars today; adoring fans purchased and collected them. Efficiency in printing and competition among publishers kept the price low enough for everybody to own a print at the cost of a bowl of noodles. Ichikawa Danjūrō V as Hannya no Gorō in Shibaraku (x.x) was an advertisement for the theater.

In yakusha-e, an actor appears in his role. The actor Ichikawa Danjūrō V (x.x) was captured in his role as Hannya no Gorō in the play Shibaraku; for this role, he wore an elaborate wig, and his face was painted in red and white. He cut a menacing figure with one arm, lifting his sword and sporting a dramatic frown. Shunsho was known for creating more realistic portrayals of actors and close-up portraits consisting of the heads and torsos of actors.

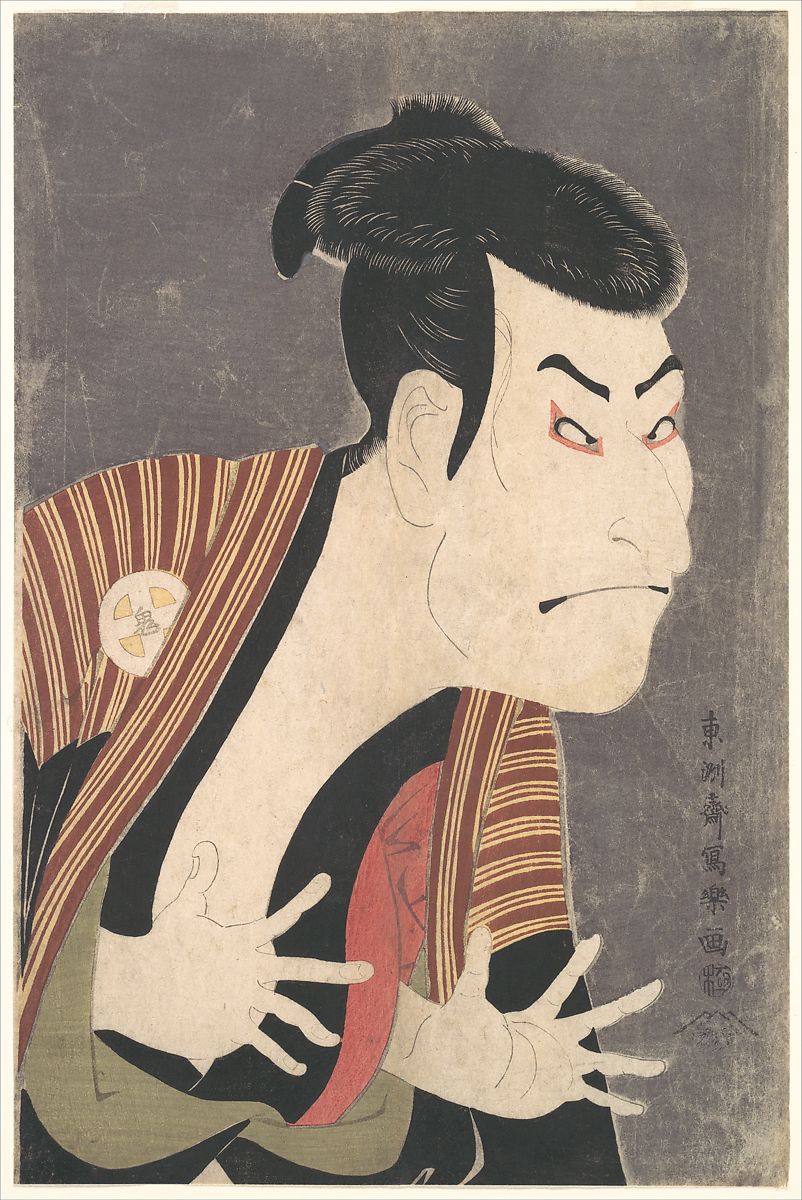

Toshūsai Sharaku

Toshūsai Sharaku (active 1794–1795) designed the most expressive depictions of Kabuki actors in the head-and-torso-only format. With realism unusual for the time, Sharaku managed to capture the personality traits of Kabuki characters. The print of Ōtani Oniji III as Manservant Edobei (3.5.9) is iconic among Sharaku prints. Sharaku utilized hand gestures and facial expressions to indicate Edobei’s wicked dramatis persona. Edobei was about to rob someone; Sharaku accentuated this impeding action by showing him leaning forward with his two hands opening wide, ready to grab its prey. Already unattractive with his oversized, hook nose, evil Edobei is glowering with an exaggerated frown and an upturned mouth. Sharaku used only three lines to represent the pent-up tension of the moment. One curving line indicated his taut jaw, and two “S” shape lines on Edobei’s temple indicated two strands of hair escaped from his otherwise pristine coiffure. The lines are so fine that from afar, viewers may have mistaken them for trails of sweat. Capitalizing on this visual ambiguity, Sharaku managed to represent both signs of stress with an economy of lines.

Very little is known about Sharaku. Only around 140 prints by him were produced in the ten months between 1794-95. After that, the name and the stark realism a la Sharaku disappeared. Some experts believe that Sharaku’s prints were too unflattering, closer to caricatures than portraitures, and thus, they lost their customer base. As for the artist, some speculated that the name is an alias of another artist, and it ceased to be used once people lost interest in Sharaku-style prints.

In the early 19th century, landscape prints became popular due to the rising interest in travel and tourism. People wanted to learn about other parts of Japan beyond their domain. Landscape prints functioned as souvenirs for travelers who had visited a site, or the prints reminded people of places to stay in the future. Two of the most significant landscape print artists were Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). The prints of both artists are well known in the Western world, inspiring modern artists such as Monet, Whistler, Degas, and, Van Gogh in the second half of the nineteenth century and beyond.

Katsushika Hokusa

The challenge in creating prints in a series is creating variations around a theme, variations intriguing enough to keep customers buying from the same series. What makes 36 Views of Mount Fuji interesting is the variety of human activities set against different landscape views in each print. In Nakahara in Sagami Province (3.5.10), the main interest is people from different walks of life converging around a bridge over a small river, some locals and others travelers. The fishermen on the left, the woman with a baby and round tray on her head, and the peddler near her were local people, while others were travelers; generally, pilgrims as the area is near a religious pilgrimage site. Mount Fuji -- visible at the center – does not provide a stage for a more exciting composition as in The Great Wave. In this print, the joy stems from learning about the slice of life in everyday nineteenth-century Japan.

Hokusai’s The Great Wave of Kanagawa (3.5.11) is arguably the most iconic, well-known ukiyo-e print in the world. With limited colors and shapes, Hokusai created a masterpiece of composition. The print came from a series of 36 Views of Mount Fuji, and although the mountain is barely visible in the background, Hokusai ensured that the viewers would not miss it. The giant swirling wave is a half-circle that, if completed, frames the mountain. The stylized fringes of the waves form menacing claw-like talons that threatened the boats yet also pointed towards Mount Fuji. The larger triangle created by the wave in the foreground mimicked the small triangle of Mount Fuji. The primary color in the print is Prussian blue, a synthetic pigment recently introduced in Japan. Hokusai was one of the first artists who embraced this color; it appeared on almost every print in this series.

Utagawa Hiroshige

In the Edo period, Kyoto and Tokyo were connected by two roads. Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) traveled through the Tōkaidō road in 1832, making notes and sketching sceneries along the way; these became the basis of 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō. This is arguably the only series that can match the virtuosity of Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mount Fuji. Both series tell the stories of human lives in landscape settings, and both demonstrate compositional mastery. Hiroshige’s series is more lyrical, representing different weathers and various times of the day, and changing seasons factors influenced the mood of the print. The frenzy in Sudden Shower at Shōno (3.5.12) is palpable; people are running up and down the slope to avoid the summer downpour. Multiple diagonals – some as shapes and others as lines – in different directions add to the frenetic energy of the moving bodies.

In contrast, calm and stillness pervade Evening Snow at Kanbara (3.5.13). Hiroshige prioritized mood over objective veracity in depicting this site as Kanbara is a coastal town in Shizuoka Prefecture, and it rarely snows there.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) is considered to be one of the last ukiyo-e masters and portrayed not only bijin-ga and kabuki actors, but a wider set of samurai heroes, cats of all types, and mythical animals, frequently including satire in his images. He learned to draw at an early age and quickly became an apprentice of one of the masters in the Utagawa school. He studied European art and regularly arranged his images in landscape orientation.

Onmayagashi in Edo (3.5.14) depicts three men struggling to stay dry under one umbrella passing the fisherman casually walking in the rain who is trailed by a single man carrying three umbrellas, rain splashing everywhere. Kuniyoshi often added subtle humor to his works. He used muted colors of the shadowy background and boats, bringing the activity of the scene to the foreground.

A Lovely Garland (3.5.15) is based on the story, The Great Woven Cap, the adventures of an ancient courtier. A diver recovered jewels from the dragon king who lived in the sea and with a dagger in hand, battles the octopus. Kuniyoshi uses tones of blue for the background to set off the ongoing battle, contrasting the diver’s elegantly patterned robes.

Ukiyo-e prints were very popular, a small piece of art available to all classes of people, not restricted as expensive paintings. Thousands of prints were made; however, the survival rate is limited because of the materials used to make the prints. The dyes faded from exposure to light and the paper deteriorated from handling, poor storage, or contact with acidic materials. The term ukiyo-e translates into ‘pictures of the floating world’, and the surviving prints give an insight into the Edo world, environment, and lives of the period; the samurai warriors, the kabuki theatre and actors, the rise of the courtesans and the engaging landscape of Japan.

[1] Lower ranking samurais did frequent the pleasure quarters, associated with merchants and artisans, and participate in these activities. However, the term chōnin typically refers to non-samurai participants of urban popular cultures.

[2] Regarding artist names: Full name will be used for the first time. After that the artists will be referred to by their first names according to the typical convention of referring to Ukiyo-e artists.