3.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 120740

Introduction

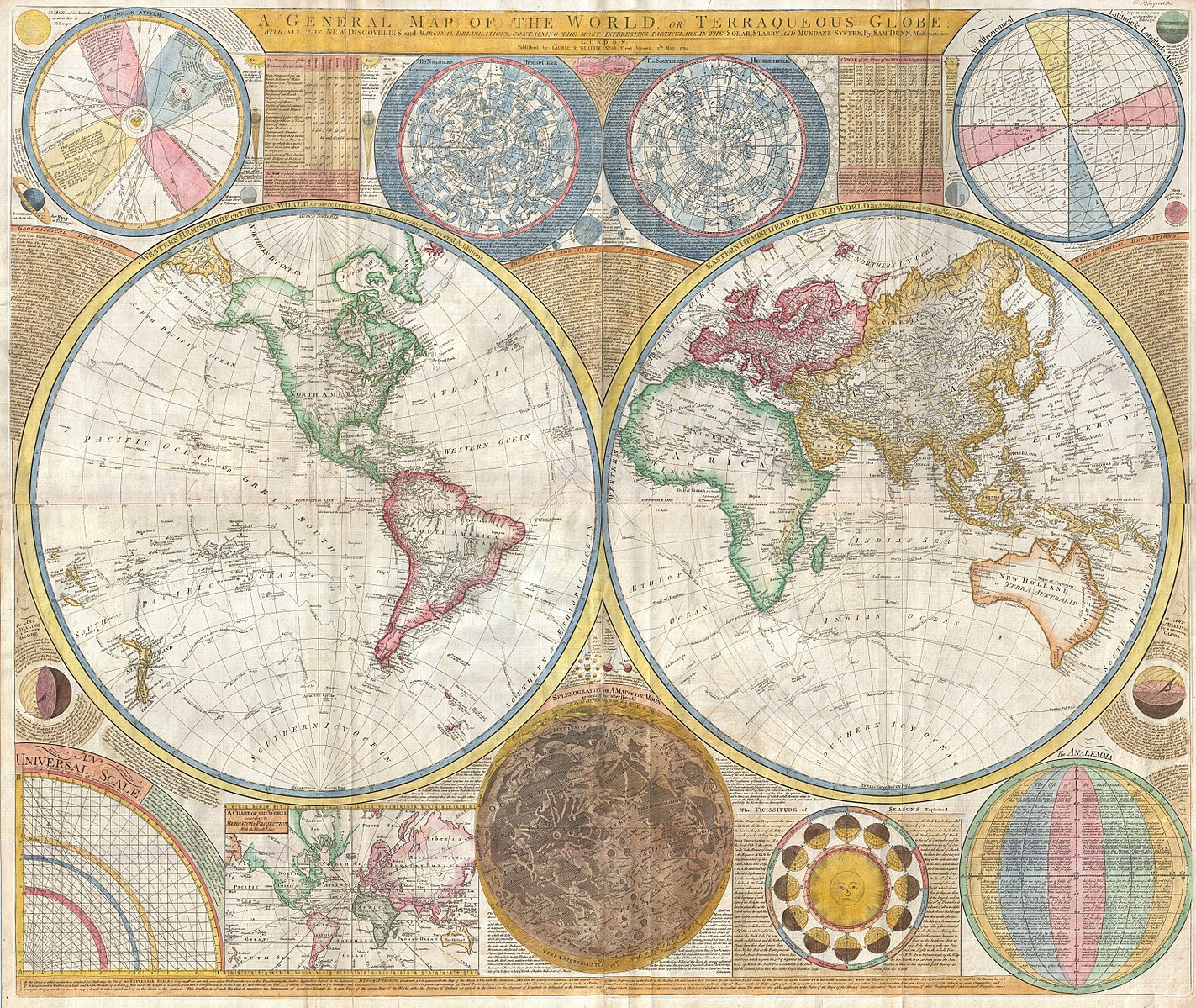

In 1794, the world map in the format of a double hemisphere (3.1.1) and made by the mathematician Samuel Dunn of England included all the lands discovered by the European explorers. The map was surrounded by scientific calculations, star charts, a presumed moon and solar system map, a seasonal chart, and other miscellaneous concepts. Little was known to the European mapmakers about the geographic extent of North America; however, Captain Cook had explored some of the northwest and mapped his concept of the coastline. The area west of the Mississippi remained unknown, especially the massiveness of the Rocky Mountains, as explorers continued to search for the elusive river passage to the west, into the Pacific, and across to Asia. Little was known about the interior of South America, although the eastern coastline was well mapped. In the Pacific Ocean, a few islands were noted on the map. Oddly, the map did not include Antarctica; although the region was designated on earlier maps, the area was still speculative and had not been explored. Exploration and colonization created a global geographic knowledge of the general outline of the world during this period.

Population movement changed the societies of the old world as new cultures were established, causing massive upheaval among indigenous people throughout the Americas. People had traversed Europe and Asia for centuries, fighting wars, trading, and continually realigning borders. However, the intrusions of Europeans during exploration and colonization into the new continents were devastating to the indigenous populations. The Europeans brought different concepts of ownership, destructive weapons of war, and new types of materials. Many of the local people in the Americas were forced into servitude or slavery, converted to new religions, their land and wealth confiscated.

Africa

Africa, through ancient times, had developed different and successful civilizations and societies. On the vast and varied continent, some governments were small, village-based structures. In contrast, others were large kingdoms ruled by kings, all with governmental organizations, societal rules, economic systems, religious beliefs, and artistic establishments. Initially, each diverse culture utilized the region's natural resources, ultimately expanding into trade partnerships along the trade routes within geographic areas and then into Europe and Asia. Slavery, as in many other civilizations, was frequently part of different African cultures. Slaves, usually captured by skirmishes during regional warfare, built pyramids, harvested crops, and mined for gold. Starting in the 1500s and reaching its peak in 1800, the transatlantic slave trade devastated African societies, depopulated large swaths of the countries, disrupted trade and societal structures. The addition of the European's intrusive colonization, colonial rule, and ignorance of African history, cultural standards or institutions, brought widespread disruption to most African countries, a problem still existing today.

Slavery among African regions had long been practiced; however, it was not based on race. They captured people in wars or who committed crimes. Slaves were used for the local agriculture or industry and frequently a specific term, not a lifelong sentence. As the European need for labor in the new colonial regions grew, the impact on western and central Africa was significant. Leading African rulers captured neighboring populations in large-scale raids, trading the humans for textiles, food, or tobacco, and especially access to guns and alcohol.

"The transatlantic slave trade can also be understood through its sheer magnitude: for 366 years, European slavers loaded approximately 12.5 million Africans onto Atlantic slave ships. About 11 million survived the Middle Passage to landfall and life in the Americas."[1]

The excessive profits made from the slave trade by Americans and Europeans propelled the exceptional economic growth in those regions. The trade was highly organized; Spain controlled all the slave imports into Spanish America and the Caribbean; France, England, and the Netherlands controlled North America and other regions. Major ports were constructed, and ships were built to import slaves and export back to Europe luxury goods, manufactured textiles, armament, and liquor; excessive profits were made on the imported slave and the slave's labor.

European intrusions and disruption were also devastating to African art. Europeans viewed art as something unique and irreplaceable. Non-Western art was judged as just utilitarian, simple, not unique, and therefore, not art. The Europeans took African artifacts to Europe, souvenirs of their trips, objects for natural history museums. The "other people" were not considered civilized and did not create "real" art, only curiosities. In the twentieth century, "other art" became classified as art and moved to galleries and museums. Although much of the art was confiscated, melted, burned, lost, or decomposed by nature, art was a meaningful and vital part of African culture's economic and social histories. The medium applied, how much decoration was involved or how it was used might define its economic importance; if ivory was a valuable medium, it generally was made for and operated by a ruler or elite person. If art was mainly located around a religious building or statehouse, the place was influential in the social structure. Personal art, whether clothing, a hat, or a mask, defined social mores and economic status. The artwork was not only something of beauty and creativity but "ultimately art history is relevant to general history because of two special properties: the concrete character of works of art and the fact that trends in art directly document meaningful change at large."[2]

Europe

Europe was in continual upheaval from battles for territorial and expansion rights. At the beginning of the 1700s, Charles II of Spain died without an heir, leaving the Spanish Crown's possessions to the French Duke of Anjou and grandson of Charles II's half-sister, Marie-Thérèse. However, Charles II was a Habsburg, and the Austrian Habsburgs believed they should inherit the domain of Spain and started the long war of succession against the French. In Russia, Peter the Great took territory from Sweden, including the region of St. Petersburg. Prussia and Austria had their battles of succession. Near the end of the century, the concepts for the French Revolution were beginning to foment, leading to the turmoil in France and followed by the rise of Napoleon.

While the competition for territory increased across Europe, the battle for trade routes and foreign territory also expanded. Portugal and Spain invaded and colonized parts of the Americas, the coasts of Africa, ports in India, and some of Eastern Asia in the 17th and 18th centuries. Spain rigidly controlled their colonies sending all treasures and profits back to Spain. When the French, Dutch, and English saw the success of Spain, they also entered into the lucrative business, establishing trade organizations in India and China while sending waves of people to colonize and live in the Americas. The Europeans practiced settler colonialization by moving their citizens into territories and decimating, resettling, or enslaving the indigenous population, or they entered into a form of exploitation colonialization, using military force to control the population and extract the natural resources.

By the middle of the century, the Europeans shifted from the concept of importing foreign products to markets, now needing to import large quantities of raw materials to feed the demanding industrialized manufacturing processes. The European entities controlled both the colonial and indigenous populations with superior armaments and advanced transportation. Near the end of the century, the French were defeated by the British. France lost most of its colonies, leaving England and Spain as the major powers in the world. Britain was now in the position to control most of India, defeat the indigenous populations of Canada and move across the rest of the globe, a concept first upset by the revolution in the American colonies.

In Europe, refined young men embarked on the Grand Tour as their rite of passage, traveling through Europe and especially Italy to study art and antiquities. As they toured, purchasing a painting, Venetian glass, or a Greek vase became part of the attraction and education. In France, art dealers or marchand mercier and the commisseur-priseur or auctioneer gained prominence and more influence than the salons. Until the 18th century, England was not a primary art market. In 1735, they enacted a new intellectual property ruling protecting visual arts, a law already applied to literature. Auctioning art developed into a new market and the beginning of major auction houses of Sotheby and Christie. Art was an investment for those with flexible incomes, selling when they needed money or purchasing in better circumstances. Using art dealers and auction houses brought flexibility into the art world.

India

India had long been in the middle of the trade routes between Asia and Europe, although it had maintained its governmental structures and controls. At the beginning of the 18th century, the Mughal Empire collapsed, leaving multiple weak Indian states headed by individual leaders. As control of the trade in the region among the European powers grew, the desire and ability to dominant led to military intervention and eventual control by the British. England used India as a trading post in the 1600s. By the beginning of the 18th century, under the power of the British East India Company, they established forts, manufacturing sites, shipping ports, and settlements in Kolkata (Calcutta), Mumbai (Bombay), and Chennai (Madras). While trading in cotton and silk materials, they also started to compete with the Dutch control of the spice trade. Throughout the 1700s, England increasingly expanded control as a ruling power of India and Burma along with the lucrative ports of Singapore and Hong Kong. In India, at the end of the 1700s, they ruled most of the southern part of India.

By the mid-1760s, the East India Company used private armies. It became the principal ruler in India until the English government took control, exploiting and taxing the people, controlling them with military force. Trading documents recorded sales of textiles from India, accounting for sixty percent of the East India Company, a company that grew rich on the backs of the low-paid workers.

"The company purchased many fine Indian textiles, including muslins, painted or printed chintz and palampores, plain white baftas, diapers and dungarees, striped allejaes, mixed cotton, and silk ginghams, en embroidered quilts. Indian craftsmen were masters of colour-fast dyeing techniques and many fabrics showed wonderful designs and colour combinations produced by hand-painting and wood-blocking."[3]

Under the imperialism of Britain, artists came from multiple European countries not to embrace or study the art they found in India; native art was generally not considered proper art. Artists who came started a new genre of art, watercolor painting, illustrating scenes of life in India of ordinary people working in the fields to activities of the court. The market for this genre was outstanding in Europe, and some artists successfully painted the local culture and sold their work in Europe.

Japan

Japan, in the 1700s, continued the Edo period under the control of the military Tokugawa shogunate feudal government. The government continued the policy of isolation while growing the economy within the country. Strict codes of law were enacted, defining all types of conduct from how marriages were performed, the appropriate dress, how many castles could be constructed, and the weapons style. Trade was constricted to specific ports, and European Christian religions were banned. The societal structure was established on rigid and stylized inherited positions with the emperor, court nobles, and the powerful shogun considered the elite and ruling class. The second level was held by the formidable samurai, the military might of the country. Below them were peasants, craftsmen, and merchants. Each group understood and lived within the rules governing their position. Buddhism and Shinto were the prevailing religions; however, during this period, neo-Confucianism re-emerged, influencing the laws.

The role of women was also defined; married women managed the home, love was not part of the requirement. The shoguns were surrounded by wives and concubines, daughters and mothers, and female servants, all part of the household. Other men generally found sexual or romantic friendships with courtesans who lived in specified areas outside the home. During the 18th century, the pleasure centers became entertainment arenas, and the new, specialized geisha profession began. Initially, the geisha were males who entertained the men waiting for a courtesan; then, the word geisha was adopted by females. The geisha was skilled in singing and dancing, working as entertainers instead of just prostitutes, wearing specified fashionable clothing.

The arts and entertainment became an essential part of the Japanese lifestyle. Along with the geisha, kabuki theater, puppet theaters, and literature, painting and woodblock prints were a significant form of art. Ukiyo-e was the genre of printmaking responsible for the immeasurable diversity of images from this period in Japan, illustrating all aspects of life; landscapes, ordinary people, folklore, military scenes, or nature itself. Ukiyo originally was based on the early Buddhist meaning – "world of sorrow"; however, by the Edo period, the word represented "the floating world" and a more hedonistic attitude, perhaps both have applied to the feeling of a need to escape. In the book Tales of the Floating World, Asai Ryoi wrote:

"living only for the moment, savouring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake, and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: this is what we call ukiyo."[4]

Mexico

Mexico continued under the calamitous control of the Spanish in the 1700s as a part of the grand Spanish Empire, La Nueva España (New Spain). The indigenous population was decimated, in poverty, and continually controlled by the clergy and the increasing numbers of people born in Mexico of European descent – the criollos. The encomienda system, a land grant defined by the king of Spain, gave the colonists the property right and forced labor from the native population in the area. The king in Spain oversaw economic activities, took its twenty percent of mining activity, determined trade policies, and forced conversion to Catholicism. The Spanish had to import African slaves to rectify the labor shortage. Jesuits, an order of Catholic priests, held significant power, almost operating as a separate state within the overall governance structure. The Spanish Crown had them expelled from Mexico, causing unrest from those who believed the Jesuits were special protectors of the people from the whims of the crown. Both the indigenous and criollo populations were supported by the Jesuits during the hard times and resented the expulsion. In this period, Spanish territories also produced the same amount of silver as all the world combined. The incredible output came from native labor who worked excessive hours with a high death toll, adding to the unrest in the countryside. The colonial control by Spain lasted until 1810, and the revolution came.

By the end of the century, a significant and established caste system was in place and enforced by the laws. The highest level were those from Spain (peninsulares) who usually traveled back and forth, the only people who held controlling positions. Below them were the descendants of Europeans who were born in Mexico (criollos). They did not hold office, were generally prosperous, and could wear silk clothing. Other levels were defined by a complex combination of ethnic backgrounds of European, native, and African slaves. For example, a mestizo had one European parent and one native parent, a castizo had one mestizo parent and a criollo parent. Other people were classified as cholo, mulatos, or zambos, depending on their parental identities. Society was further divided by predominant physical characteristics. The lowest levels were slaves owned by another person and the indigenous people, who were considered wards of religious organizations and the Crown.

By the beginning of the 18th century, most artists were now born in the new world or indigenous and they began to diverge from the traditional European standards as images of the brown Virgin of Guadalupe became a central theme in paintings. Artists also incorporated the history of the Aztecs or native heroes. Wood carvings of saints and religious figures were an important art model and movement to counter European classicism with excessively ornamented and excessive church façades and interiors.

North America

North America was dominated along the east coast by settlers from England and France, while Spain moved from Mexico into the southwest. In some regions, France and Spain maintained their control of territories while in the late 1700s, the colonies unrest with English rule grew into a revolution and the establishment of the United States, a conflicted association with some of the states and their major landowners. The north was populated with larger cities and small farms as the southern states' economy was based on great plantations dependent on slave labor.

Native peoples had no concept of land ownership; they believed the land and its resources were available to all, living in areas with sufficient water and food sources, moving when necessary. The Europeans believed the land belonged to an individual, and as they established colonies, they built houses, defined fields, and erected fences, demarcating the property as belonging to them. Native tribes no longer had freedom of movement, causing conflicts with the settlers. By the 1700s, the native populations in the colonies began to lose control of their territories and way of life. European commodities flooded the regions, and native people adopted the textiles, utensils, and even the flint and steel to start a fire. Weapons brought a significant change to the practice of war as imported metals made stone arrow points and axes obsolete; the prized possession became the musket or a long-barreled pistol. Access to weapons changed the traditional balance between tribes, weaker or unarmed groups almost eliminated.

In the early 1700s, many colonies existed in segmented populations, whether controlled by England, France, or Spain. The new territories brought land and space to grow crops highly valuable on the trade routes, particularly sugar, tobacco, and cotton, all requiring labor. In England, most of the labor was based on the concepts of a low wage servant, however, even when they imported indentured servants to the colonies, the demand for workers exceeded the availability and they quickly turned to imported slaves from Africa. Between 1600 to 1800, over nine million slaves[5] were brought from Africa to North and South America and the Caribbean, around 500,000 to the United States, the biggest forced migration ever recorded.

Museums in Europe

The word museum derives from the nine Muses of Greek mythology, the deities who inspired creation in philosophers and writers as they traditionally appealed to the Muses before they started to write. The Muses were not absorbed in human activities; instead, they dedicated their lives to the arts. A few museums were established through the early centuries as conquerors displayed their plunder or a few prosperous people collected artefacts and displayed them in private cabinets. The earlier established museums included the early Capitoline Museum constructed in 1471 to hold a collection of ancient Roman art and archaeological finds followed by the Vatican Museum in 1506 to contain the vast collection of the Catholic Church, including many from the Renaissance.

The modern museum concept blossomed in the 18th century in Europe, a time of enlightenment for them as they colonized other parts of the world, finding new ideas, new cultures, new animals, and plants. However, what were the real ramifications of objects exhibited in the new museums? The British Museum started in 1750, based initially on specimens from colonies in Western India, expanding to incorporate materials and artefacts taken from other territories. In Rome, the expanded Capitoline Museum opened in 1734, originally to house the Roman statues collected by Pope Sixtus IV. After Louis XIV moved to Versailles, the Louvre Palace held the royal art collection. With the advent of the French Revolution, the building became a national museum opening in 1793, exhibiting the works confiscated from royals and the church. Other museums were opened; the Museo del Prado in Madrid (1785), the Hermitage in St. Petersburg (1764), the Uffizi Gallery in Florence (1744), as well as those in other cities.

Previously, the elements considered art was not made for display in museums; they were created for religious institutions, the personal use of the wealthy, or confiscated artifacts from other places. By moving the original location, museums became filled with paintings, sculptures, furniture, or architectural elements. Museums became repositories, collections of cultures and their histories and structures, arranged and divided by movements or national definitions. Museums became influencers in art and the art market; what is art or the perception of art, and what should be included. Fortunate was the artist whose work was hung in the museum.

Kente Cloth in Africa

Although the origins of Kente cloth and its narrow patterns are unknown, legends passed through the generations about the original inspiration. The most popular legend described two brothers who observed a spider weaving a web and wanted to recreate the pattern. Whatever the inspiration for Kente cloth, the process and definitions are a special part of the textiles and clothing of the region, a practice continuing today. In the 18th century, the cloth was made from silk or cotton with unique patterns and colors, the woven cloth reserved for the royal families during special ceremonies. Silk fabric was imported; however, the plain patterns were unacceptable. The women took the fabric, carefully unraveled the silk threads on the looms, and made Kente cloth.

Kente cloth is woven with a narrow horizontal loom about four inches in width to create a thin fabric band. On the loom, the rows of warp thread (vertical) are crossed with the rows of weft thread (horizontal). Each loom has two to six heddles (loops to hold thread) to control the warp threads. The weaver uses foot pedals and a shuttle to weave the thread. Both the weft and warp thread colors are used to create the patterns. Every pattern has a name, usually assigned by the weaver or a head person, and a name might signify any special event, values, achievements or ideals. Colors and their symbolic meanings are a vital part of the cloth. When a very long piece of fabric was completed, it was cut into pieces at specific intervals and sewn together with the selvage edges. Some of the pieces might be turned at a right or mirror angle, producing the various Kente cloth.

Woodblock Prints in Japan

Producing the ukiyo-e woodblock prints was a complex process with multiple steps, each generally completed by a different skilled person. The process started with the artist (credited with the work) and a contract with the publisher. As in any artistic endeavor throughout time, sometimes the artist worked for a single publisher, a publisher may discover an artist or artists freelanced. Artists started the process by making a sketch (gako) and adding details in some critical areas. If any additions were made, the artist glued paper on the area and redrew the corrections. When the artist completed his work, a copyist created a perfected black and white drawing which the censors reviewed before going to the carver. The carver used a block of aged cherry wood and pasted the drawing face down on the block; the paper was removed, leaving the lines as the guide for carving. The block carver had to create one block per color, and an ordinary print may have over a dozen colors. The master carver finished any detailed patterns. A key block defined the registration marks for each block. Printers were the third set of artisans, grinding pigments, mixing with water to produce ink, and applying the ink to the block. Generally, several sheets of paper were printed before moving to another color in a fixed sequence from light to dark and at the end the blacks, any shading applied with a brush or cloth. Each impression of the print varied on a single run, and a print may have two hundred or a thousand copies.

Churrigueresque in Mexico

Churrigueresque is an elaborate architectural Mexican Baroque style of sculptural ornamentation in architecture resulting in no wasted plain space. Named after Jose Benito de Churriguera, an architect and sculptor in Spain who obsessively filled in any space of a façade. The flat surfaces of the outside facade, columns, or altar in the church became canvases for artists to fill with elaborate ornamentation. The decorative work was molded, painted or gilded stucco or tiles forming shells or garlands, rolling cornices, or revised volutes. When the style was imported to the new world, the Churrigueresque column or estipite became the standard motif. It was shaped like an inverted cone with a wide shaft through the middle and adorned with ornate vegetative embellishments.

Mexican Baroque Architecture in Mexico

Interactions between the Spanish European design aesthetics and the traditional native design concepts became the mixture leading to the hybridized ideas and structures of new architecture, particularly in cathedrals. The church was integral and the center of a community, partly representing the Catholic church's influence and the identity beliefs of the population, "the Baroque style in Mexico evolves according to its own particular nature."[6] The excessive adornment and new methods became the standard, especially the use of plasterwork combining curved, straight and intermixed lines covering columns and altars with exaggerated tiny carved motifs whether angles or Aztec gods, scrolls, arabesques; no space left unfilled. The raised plasterwork is generally made from lime plaster; lime was transported from mines in Hidalgo by mule and boat along the lakes. Mixed with water, lime created a relatively dry mixture; sometimes, the lumps were left as an aggregate to hold the plaster.

Colonial Art in America

Early colonists had little time for art, survival, and religion dominated the lives of the people. As soon as the colonies stabilized and more settlers came, craftsmanship developed, and artistry grew. Large, ornate churches and palaces did not exist; outsized marble sculptures were unimportant in the small, plainly painted churches. The new colonists turned their skills to smaller, portable endeavors; portrait painting, silversmithing, furniture making, proper outlets for creative people. Hundreds of silversmiths flourished, turning useful everyday items into elegant works of art, hand designed and crafted. Furniture craftsmen were found in every town, making furniture that fit into the culture and surroundings of the new lands. Much of the work was simple for their local village, however, some of the work moved into the category of fine art made by professional artists, usually created for a wealthier clientele.

Painting portraits became one of the first major artist roles, a luxury item and reflecting a person's economic or religious status. A person usually posed with a favorite possession, further developing their position in the community. As the interest in portraits grew, training for artists increased, no longer the purview of an iterant folk-art painter, the education and skills of artists flourished, and portraits became a significant art form for the new colonies.

[1] Retrieved from http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0002

[2] Vansina, J (2014). Art History in Africa: An Introduction to Method, Routledge. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=_MYFBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT219&lpg=PT219&dq=african+art+1700s&source=bl&ots=joTbCXrlP8&sig=ACfU3U2e4T8QofvfkkYI0yGatMlzowl41w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwibpbWXnonpAhUWoZ4KHSDUAYU4ChDoATAIegQIChAB#v=onepage&q=african%20art%201700s&f=false

[3] Retrieved from https://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/texts/empire/india/bengal/bengalgoods.html

[4] Retrieved from https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=23624

[5] Retrieved from https://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates

[6] Bondi, C. (2011). Design Principles & Practices An International Journal, Shaping an Identity: Cultural Hybridity in Mexican Baroque Architecture, Vol 5, Issue 5, p 449.