3.4: Neoclassicism and Romanticism (1760-1860)

- Page ID

- 120743

Introduction

Neoclassicism and Romanticism crossed the late 18th and 19th centuries, developing into opposing styles. Neoclassicism developed first after the excesses of the Rococo and Baroque periods, bringing a more classical restraint and resurgence of Greek influence. During this period, some classical Greek sites were under excavation, providing additional inspiration for classical images. Neoclassic artists used sharply defined lines and brushstrokes, creating smooth areas. Other artists wanted different expressions of emotion and defined Romanticism based on historical events and natural landscapes using visible brushstrokes, less restrained. The concept of a public museum was founded where paintings and sculptures were available for the general population to view. Napoleon established the Louvre in France as one of the first major public museums, incorporating a majority of the art from previous kings, hung in the old palace, and now a place of the people.

The process of painting was also revolutionized in this period. Making and storing paint was laborious; each color mixed by hand with the appropriate raw materials, a struggle to keep the mixed paints from drying before the artist could use them. The primary method of storing their mixed paint was in a pig's bladder. The artist stuck a pin in the bladder to squeeze out the paint; however, the hole was difficult to cover, and the bladder tended to break when moved. Artists drew sketches outdoors and returned to their studios to paint the actual image. John Rand, an American painter, experimented with forming tin into the shape of a tube and adding a screw cap. Now his paint could be stored and easily reused. Acceptance of the tube concept was slow until the Impressionist period, when the ability to purchase paint in tubes allowed artists to move outside and paint the world in place.

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism paintings contained clean, well-defined lines of heroic figures, especially those of ancient classics. They believed classical Greek artwork displayed the proper techniques and followed the Greek standard for human proportions. The Neoclassicism artists were also enamored with the political philosophies from ancient cultures and used them as a guide. Artists used chiaroscuro techniques, contrasting light colors against dark tones to add drama, controlling the minimal amount of color. The paint was applied with a smooth surface, brushstrokes seldom seen, blended into the painting.

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) was the champion of the Neoclassicism style, an influential painter who supported "…rigorous contours, sculpted forms, and polished surfaces…intended as moral exemplars."[1] He painted for royalty as well as revolutionaries and brought many well-known artists under his tutelage. His early paintings were historical, based on ancient civilizations, the style usually supported by the French Academy with an austerity not found in the Rococo style. After the revolution and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, David became the primary painter for the emperor. David and his students painted the exploits of the emperor and his empire, the artwork full of textural elements of lace, fur, or satin; all painted without any visible brushstrokes, a smooth polished surface.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps (3.4.1) depicts an idealized version of the mighty Napoleon at Saint Bernard Pass in the Alps, leading the army through the rocky mountains. David painted five different paintings of the same scene with slight variations of color in the background, the horse or the rider. Napoleon appears to sit easily on the horse, rearing up on the small rocky ledge. The wind seems vigorous as the cape and the horse's mane are blowing in an unusual direction. The red cape centers the image and gives movement, pointing upward in concert with Napoleon's hand. The horse is posed in a classical style of ancient statues, helping to enhance Napoleon's power and strength. In reality, mules were used to cross the Alps, and Napoleon would have worn a heavy coat; any horses were led across the challenging rocky terrain, but David was not paid for reality.

Historians believe The Death of Marat (3.4.2) to be the finest work of David. Marat was a physician, a leader in the revolution, and a paper writer for the people who helped ferment the revolution. While Marat was in the bath, he was murdered by a woman who supported the aristocracy. The painting appears to happen minutes after the murder; Marat's head and arm have become lifeless as one hand still holds the paper he was writing. "Scholars have seen this vision as a revolutionary pietà because of the repose of the corpse, so different from that of a normal body in a stage of rigor mortis."[2] The arm also hangs down, very similar to Michelangelo's Pieta.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) was born in France, his father was an artist. Ingres first studied art in one of the academies before becoming an apprentice to David, the most famous artist in France at the time, learning classical literature, mythology, and archaic art. After two years, his talent for Ingres was acknowledged, and he went to the prestigious Ecole Des Beaux-Arts, becoming a portraitist and entering several paintings into the Salon. Ingres became known for the details and textures in his painting, eventually experimenting and moving from classical Greek subject matter to more contemporary themes. He still maintained his focus on the importance of the drawn line instead of the power of color.

Oedipus and the Sphinx (3.4.3) portrayed a story of Greek mythology when Oedipus was confronting the Sphinx, who is seen as a part woman and part lion with the wings of a bird. Oedipus answers the question the sphinx asked all travelers who want to pass through the land, the bones of unsuccessful travelers seen at the bottom. Near the entrance is another traveler who waits in fear, the city of Thebes dimly depicted. The background is dark with muted light on the central figures, composed in a classical Greek story. I

ngres used a live model who posed in the same posture as Hermes Fastening His Sandal (3.4.4). "It is a pose which accentuates the musculature of the model's body, making him appear strong and determined. His body, limbs, and the javelins that he is holding all form geometrically harmonious shapes."[3]

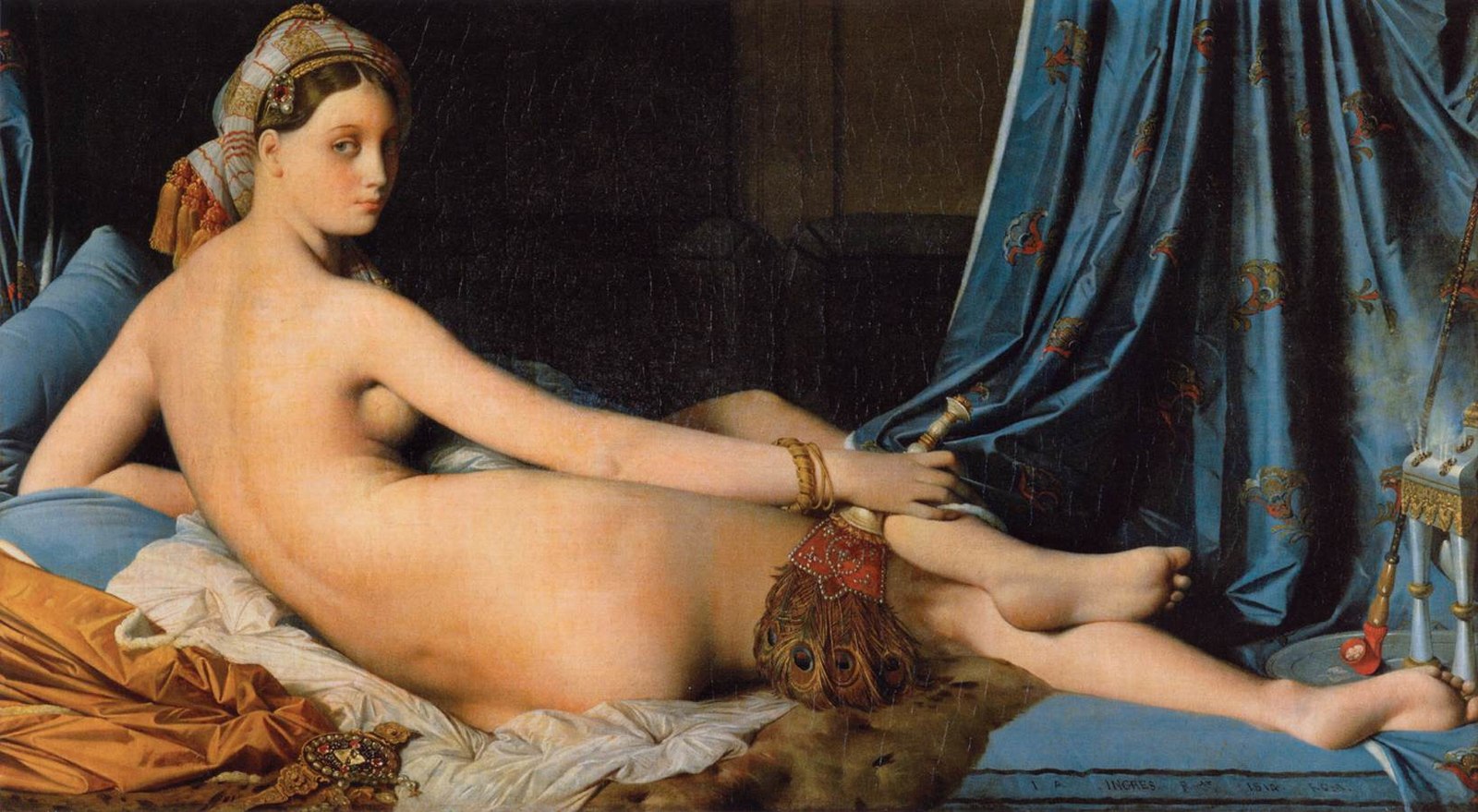

The Grand Odalisque (3.4.5) represents a change in the artwork of Ingres from Neoclassicism. However, the nude female figure is classic, especially those of Aphrodite, and he used a contemporary subject matter for his painting. The work is known for its unusual and unrealistic proportions. The odalisque (concubine) has a small head with overly elongated arms and legs, the body so distorted a figure would need extra vertebrae to achieve the pose. Although the figure is oddly elongated and twisted, it still appears sinuous yet slightly eerie. The detailed curtains, soft fabrics, jewels, turban, and hookah pipe all surround her, unusual accouterments adding to the exotic look of the painting.

Angelica Kauffmann

Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807), daughter of a muralist, was a natural painter at an early age and traveled with her father to other countries as an assistant. She learned about the old master painters and met people of the new style under development – Neoclassicism. In Italy, Kauffmann started as a portraitist and returned to England with a solid reputation, quickly establishing a portfolio of patrons. Although twice married, she did not have children, focusing only on her career and building her reputation.

She helped found the Royal Academy of Arts in London, one of the two women accepted (Mary Moser, the other woman). They were both restricted from attending any meetings or celebrations. Females were not allowed to paint nudes, so Kauffmann could not participate in painting classes with nude models. After the death of the two women, no other female artists were members of the academy for 168 years until 1936, when Dame Laura Knight was elected to the academy.[4]

The Earl of Derby and his wife were wealthy and are seen with their first son, Edward Smith Stanley, 12th Earl of Derby, with his First Wife, Elizabeth Hamilton, and Their Son (3.4.6) seated on a sofa for the family portrait. The couple was dressed in Van Dyck's style of clothing popular a hundred years earlier. The earl's red suit has slashes of blue inserts and a white-collar embellished with lace. The countess's upswept hair is adorned with feathers complementing the white bodice and sleeves, her blue gown trimmed in gold. In a family portrait, the participants are supposed to face each other and appear relaxed and engaged with each other. However, the countess seems remote, uninterested, perhaps a reflection of her unhappiness as after three children and four years of marriage, the countess left her husband for another man.

Marie-Denise Villers

The art societies in England and France were the predominant venues for artists to display their work, especially young artists cultivating patronage and advertising their work. The art salons held shows and the Salon show of 1801 in Paris is where Marie-Denise Villers (1774-1821) hung her work and created a mystery still hazy in today's world. Villers was a young painter who married an architecture student. Fortunately, he supported her career as an artist when many women were forced to stop after marriage. The first time she exhibited in the Salon was in 1799, followed by the painting in 1801, known as Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d'Ognes (3.4.7) or Young Woman Drawing.

At one point, the painting was attributed to Jacques Louis David; however, over time, researchers studied the provenance of the work and finally believed it was the work of Villers. A study of the entries in the Salon show of 1801 defined the work by Villers as "Etude d'une jeune femme assise sur une fenetre," a show in which David did not have any entries, eliminating his attribution. Since 1955, the work has been credited to two other artists until 1996; with further study, the portrait is now believed to be Villers. The young woman in the portrait, clad in white, appears to be staring at the potential viewer. The painting is backlit, the light shining on her dress and hair, her face in the shadows, an unusual pose.

Antonio Canova

Antonio Canova (1757-1822), born in Italy, was the son and grandson of stonecutters. Early in life, his talent was recognized, and he became an apprentice in the workshops of different sculptors, opening his first studio when he was eighteen, following classical style. Canova was hugely prolific and preternaturally proficient, the most celebrated sculptor and perhaps the most renowned artist of his time.[5] He produced hundreds of sculptures, frequently repeating a previous image, further improving the feeling of the sculpture. In his studio, Canova used assistants to carve the basic rough structure from the life-size plaster models, a departure from most sculptors' small-size models. He always finished the plaster model before moving to the marble. The classical artist perfecting his work, suggesting the purity of antique forms, combined with subtle, naturalistic qualities, demonstrated his technical virtuosity.

Cupid and Psyche (3.4.8) was a complicated sculpture with the wings of Cupid extending upward, his protracted legs, and the movement in the arms. Canova made two very similar statues, first creating the life-sized plaster sample then using metal pins inserted in the marble to define the pathway for carving. Canova was known for his large public monuments; however, this sculpture demonstrates his ability to create tender yet sensuous figures of Cupid awakening Psyche with his kiss.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa (3.4.9) is the second version of the same image; Canova refined this statue with additional details, streamlining the body shape, a more classical view. Perseus, the son of Zeus, stands holding the head he severed from the gorgon Medusa who turned people into stone if she looked at them. Perseus wore sandals from Mercury for speed, a winged cap from Hades to make him invisible, and the sword from Zeus helping him find and slay Medusa. Perseus is looking at the head; her power to turn a man into stone is eliminated.

Luis Egidio Melendez

Luis Egidio Melendez (1716-1780) is considered the supreme still life painter from Spain in the 18th century. He started painting miniature portraits and changed to still life later in his career. He originated from a family of painters, his father, brother, and sisters; his father helped found the Royal Academy in Madrid. However, after the father disagreed with the academy, the family split, and Luis went to Italy. A successful income was difficult without royal patronage, and Melendez began to paint still life, work to be sold to the general public. He did receive a commission from a Spanish prince to paint every type of food produced in Spain.

Melendez focused on how light, texture, and color affected the combinations of fruits and vegetables and how different objects enhanced the look of a composition. Unlike earlier still life painters, he worked in close-up view allowing the lighting to bring out the color or form shadows. Still Life with Pumpkins (3.4.10) demonstrates Melendez's ability with lighting and texture. The light shines on the end of the pumpkin, revealing the intricate webbing, illuminates the towel and its texture, and reveals the color and flaws of the bowls.

Romanticism

Romanticism was a movement starting in France and England before moving to other countries. The uncontrolled and unpredictable side of nature and the human struggle in the elements were significant in Romanticism. The heroic man was no longer the center of the painting; the natural events dwarfed the man. People were portrayed in different states of behavior and sanity, no longer the perfect posed image. The movement artists painted in layers with heavy, thick brushstrokes to depict emotions and broad brushstrokes of backgrounds, skies, or landscapes, maintaining tight lines for humans in the foreground. Color was another critical element to help portray emotions. Colors were bold, backgrounds dark or shadowed, red common in clothing or sunsets.

Francisco Goya

Francisco Goya (1746-1828), considered the premiere Spanish artist of his time, started early painting lighthearted images ending with the unusual paintings of his later life. As a teenager, he was an apprentice to one of the Spanish masters before becoming a court painter, a position he held through multiple monarchies. He became deaf from a severe illness in mid-life, fueling his pessimism and bringing darkness to his paintings. Many believe Goya may have suffered from lead poisoning, causing his illness. During this period, artists made white paint with lead carbonate, a common cause of lead poisoning for artists.

In the late 1790s, the Catholic church and the Spanish monarchy suppressed and punished sexual themes, emboldening some artists, like Goya, to embrace the forbidden ideas. La Maja Desnuda (3.4.11) was "the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art without pretense to allegorical or mythological meaning."[6] The model for the painting is unknown, and the work was not publicly shown at the time. The nude woman is lying comfortably on a bed covered with pillows while looking suggestively at some unknown person.

La Maja Vestida (3.4.12) depicts the same person fully dressed; however, she fills more of the frame, making the nude painting appear almost timid. During the Spanish inquisition, the paintings were seized, and Goya was charged but not sentenced for moral depravity.

.jpg?revision=1)

Goya maintained a country house called La Quinta del Sordo. Inside, he painted fourteen murals on the walls using dark pigments of blacks and browns, focused on human suffering, pain, and rituals, murals known as the black paintings. In 1873, a wealthy patron purchased the house and removed the murals by transferring them onto canvas. The process was poorly executed, and large amounts of the images crumbled, capturing only partial images of each original mural. The Witches Sabbath (3.4.13) depicts a large crowd of people, presumed to be witches or warlocks, gathered together for their rituals. The silhouetted dark goat, perhaps Satan, is standing on the right while the seated woman on the left seems to be waiting. Initially, the woman was in the center of the mural; however, the left side was lost when removed from the wall. Goya used thick brush strokes to apply the paint, building layers for depth and muted colors to portray the poorly lit space.

.jpg?revision=1)

Eugene Delacroix

Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863) became the leader of the Romanticism movement in France. Early in his life, he was recognized for his ability to draw and trained in the prevalent Neoclassicism style of David. His early paintings demonstrated he did not follow the Neoclassicism methods. His use of brushstrokes and unusual colors gave expressions and movement to his works, forming the basis for future trends, and he was considered one of the few remaining old master painters. He used color and the way light interacts with color to paint movement into his work. He liked drama and romance as subject matter instead of the classical Greek and Roman themes. Cezanne said of Delacroix, "Delacroix is Romanticism…he still has the most beautiful palette in France, and no one else in this country has managed the calm and the moving at the same time, the vibration of colour. We all paint in his shadow."[7]

Delacroix's most influential and famous painting is Liberty Leading the People (3.4.14), with Parisians fighting for liberty under their new red, white, and blue flag (liberty, equality, fraternity). Delacroix witnessed the Trois Glorieuses (three glorious days) as the uprising was known and instilled his emotions about the event into the painting, believing it was his patriotic duty. He made multiple sketches of different scenes, deciding to use the scene of the crowd pushing down the barricades to reach the enemy.

The female, dressed in ordinary clothes of the people from the street, centers the painting as she honorably stands and holds up the flag in triumph, fighters for liberty lying dead at her feet. Delacroix used tones of reds, blues, and greens highlighted by white to create drama in the painting. The glow of the setting sun and smoke from the cannons illuminate the panorama, providing the atmosphere of liberty. In a letter to his brother, Delacroix wrote, "I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her. It has restored my good spirits."[8]

Instead of traveling to Italy, the classic venue for artists to gain inspiration, Delcroix went to North Africa, where he believed he found enough material for generations of artists. In Algiers, he gained permission to visit a private harem, the space in a house where the women lived, off-limits to most people. There he made his sketches for the painting The Women of Algiers (3.4.15). Three women agreed to pose for him as they sat grouped on the floor with the brazier and hookah nearby. The woman who is standing was believed to be a servant. The women are dressed in traditional clothing made from rich fabrics and embellished with gold thread, beads, and braids, demonstrating their wealth. Delacroix used brushstrokes and color, dabbing the paint to produce the textual elements of the clothing. He used reflective light to create the rhythm in the painting.

Theodore Gericault

Theodore Gericault (1791-1824) was a French painter and a pioneer at the beginning of the Romanticism movement. Trained in art from an early age, he became a student at the Louvre, copying paintings of the masters and studying the configurations of horses in the nearby stables, which he used in multiple paintings. He did not follow the precise lines and smooth finish of Neoclassicism; instead used paint and a brush to develop texture and the details of the muted background.

In 1812, the Napoleonic wars were underway, and Gericault loved the military's impressive uniforms and powerful horses. One of his early paintings to enter the Salon was Charging Chasseur (3.4.16), portraying the chasseur with his sword ready, the powerful horse showing aggression, a horse prepared for war. This was the image of bravery, and the painting was well received in the Salon.

By 1814, the war was waning, and Napoleon was losing when Gericault painted Wounded Cuirassier (3.4.17). Most paintings covered an entire battle scene and the mastery of a leader or the exploits of a single horseman; however, this one focused on a single soldier and his injuries. The horse's power is visible by its stance, the body painted with obvious brushstrokes, not the smooth look of Neoclassicism. The rider seems unsure of what he should do next, limping on along the battlefield. This image was not well received in the salon.

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): Wounded Cuirassier Leaving the Field of Battle (1814, oil on canvas, 358 x 294 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): Wounded Cuirassier Leaving the Field of Battle (1814, oil on canvas, 358 x 294 cm) Public DomainWhy was one image of the rider and horse accepted and the other one harshly criticized? One art historian stated:

…In 1812 success was still in the air, whilst in 1814 everyone knew they were facing defeat…….The echoes of the cries of distress from our suffering armies on the plains of Russia resounded through the lands. Hearts were full of fear and terror. It is this universal feeling which Géricault expressed in his painting and explored in the Wounded Cuirassier…..He painted two pictures, the first about glory and the other about faded glory…[9]

The Raft of Medusa (3.4.18), an exceptionally large painting (5 x 7 meters), depicted the survivors of a shipwreck off the coast of Senegal. The ship, filled with soldiers, ran aground, and with few lifeboats, some of the men constructed a raft with room to hold only ten of the soldiers. The corner of the raft is located at the front of the painting, looking like the viewer could step into the painting and move upwards into the terror of the situation. Gericault brings the emotions of Romanticism with fluid brushstrokes giving diagonal movement. He made multiple sketches and wax figures, used live models, and studied cadavers to recreate the disastrous scene realistically. The painting received mixed reviews; some critics thought the pile of corpses was distasteful, and others liked the political theme.

.jpg?revision=1)

Caspar David Friedrich

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), born in Germany, studied art as Romanticism was growing in Europe with less materialism, and a focus on spirituality. He became Germany's leading Romanticism painter, painting landscapes without biblical images, statuary, or artificial symbols. Instead, he tried to incorporate the natural world united with solitary figures, night skies, or the mystery of morning mists, bringing spiritual and emotional feelings.

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (3.4.19) depicts a man standing on a rocky precipice looking over the landscape below him filled with fog, the mountains distant in the background. One historian described the painting as "suggesting at once mastery over a landscape and the insignificance of the individual within it. We see no face, so it's impossible to know whether the prospect facing the young man is exhilarating or terrifying or both."[10] The painting is vertical instead of the usual horizontal for landscapes. Friedrich uses the very dark color for the foreground and light colors with different sizes of brushstrokes to achieve the variety in other parts of the landscape

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), defined as J. M. W. Turner, was an English painter who used color to produce expression in his landscapes and marine paintings. Born in London, he was considered a child prodigy and even studied at the Royal Academy of Arts as a teenager. A private person, he remained unmarried although he had two children with his housekeeper. He was a prolific artist as a young man; however, he became depressed as he aged and died in squalor.

Turner frequently painted ships from many parts of Europe throughout his career; this painting was completed late in his life. The HMS Temeraire was a warship for the English navy and was known for bravery in the Battle of Trafalgar. However, the painting, The Fighting Temeraire (3.4.20), depicts the ship after its days of glory, a tugboat taking the old ship to be turned into scrap; sailing ships were no longer used as steam-powered crafts replaced them. Some historians believe Turner wanted to depict the sense of loss, the setting sun dominating the painting, perhaps the sunset image on the old-style boats. He used thick paint in yellows and reds to portray the sun's rays and the reflection in the water. Detailed components on the old ship, combined with visible brushstrokes, are painted in pale colors, looking ghostly.

John Constable

John Constable (1776-1837) was born and resided in the English countryside of Suffolk, a place he often sketched and painted in his studio. He learned most of his skills independently, only attending schools for short intervals, yet influenced by the Romanticism movement. Constable valued the area around Suffolk, and most of his landscape paintings were based on the local panoramas. He did not achieve much success in England; however, the French embraced his work.

The Hay Wain (3.4.21) is an image painted where Constable stayed as a child, and the district still endures, a place to visit, remaining in the past with the millpond, cottage, and trees. Constable's father owned the mill seen on the far-left side of the painting. Constable used coarse and clumpy brush marks representative of the Romanticism style. He studied the clouds, and instead of perfect billowing clouds, he painted them the way nature produced them, snowy through dark gray. Constable loaded a big brush with pigment for the leaves on the trees to create a natural look. He painted a bright green field, then used half-dried green and lumps of yellow on his brush over the underpainting. The standard method of depicting a garden included classical ruins with antique statuary strewn about the garden. The academy criticized the Constable for his lack of classical elements in the landscape.

.jpg?revision=1)

Two artists dominated the art scene of competing movements, Ingres, the Neoclassicism, and Delacroix, the Romanticism. Artists painted in the style of calm, grandeur with carefully defined noble subjects as expressed by Ingres or the emotional, color-laden, and turbulent works constructed by Delacroix. The dispute between the two painters and their styles continued throughout the many schools, academies, and salons.

A critic in one of the salons wrote an article in L'Artiste in 1832 about the two men and thought their work should not be shown together because their different styles brought forth too many clashing views. He stated:

It's the battle between antique and modern genius. M. Ingres belongs in many respects to the heroic age of the Greeks; he is perhaps more of a sculptor than a painter; he occupies himself exclusively with line and form, purposefully neglecting animation and color […] M. Delacroix, in contrast, willfully sacrifices the rigours of drawing to the demands of the drama he depicts; his manner, less chaste and reserved, more ardent and animated, emphasizes the brilliance of colour over the purity of line.[11]

[1] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/jldv/hd_jldv.htm

[2] Retrieved from http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/632

[3] Retrieved from https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-noti...-enigma-sphinx

[4] Retrieved from https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/arti...elica-kauffman

[5] National Gallery of Art. Retrieved from https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.2052.html

[6] Licht, F. (1979). Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art. Universe Books. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Goya

[7] Neret, G. (2003). Delacroix, Taschen.

[8] Retrieved from https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-noti...leading-people

[9] Retrieved from https://mydailyartdisplay.wordpress....-by-gericault/

[10] Gaddis, J. (2002). The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past, Oxford University Press.

[11] Shelton, A. C. (December 2000). Art History, Ingres versus Delacroix, 23/5, pp. 731-732. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/28541045/In...rsus_Delacroix