1.2.2: Art History- Men Artists in the Renaissance

- Page ID

- 128150

Filippo Brunelleschi

During the Renaissance, a large body of art was predominantly attributed to male artists since men wrote history. History, the name alone—his and story combined—was written by men about their counterparts discounting the social and cultural boundaries that denigrate women. It has been established women did not have access to education or to work as artists. They were systematically written out of history giving male artists all the glory.

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) was born in France and became one of the most well-known architects who reinvented architecture. He was apprenticed to the Arte dela Seta (Silk Merchants Guild) and became a master sculptor working in bronze. Brunelleschi was from a wealthy family and received an education heavy in mathematics, giving him the background needed to build the infamous dome.

At the beginning of the Renaissance, architecture was a resurgence of classicism, moving away from the conventional gothic design and construction style. The flying buttresses of the past, gothic buildings could not be built high enough or substantial enough to support the proposed enormous dome. Flying buttresses were uncommon in Italy and considered dreadful pediments attached to buildings. Brunelleschi went to Rome to study the ruins on Palatine Hill, learning the characteristic elements of the architecture.[14] Using what he learned in Rome, Brunelleschi used perspective to draw and create realistic paintings with three-dimensional accuracy. Thanks to Brunelleschi, the Holy Trinity by Masaccio was possible with an accurate and detailed illusion of a three-dimension two-dimensional plane.

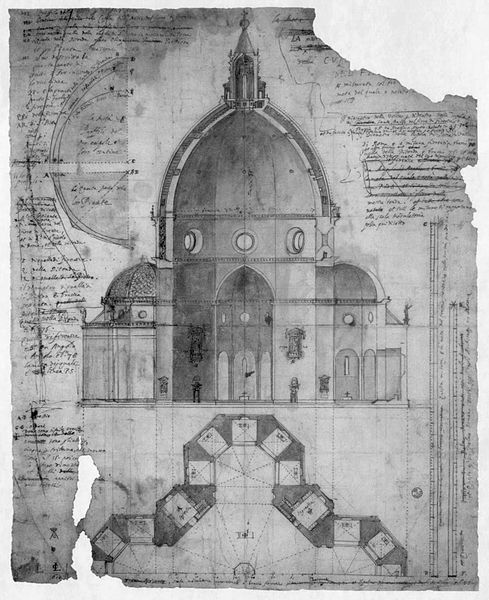

In Florence, Italy, the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower) (1.2.2.1), the main church, began in 1296 based on the Gothic construction style. The building design included an immense octagonal dome at one end of the building. Entire forests were cleared, and large marble slabs were quarried to construct a tremendous and magnificent church. It should have been impossible to build, and for over 200 years, no one could produce a viable plan to finish the dome leaving the church open to the elements and nature.

By 1418, the church had yet to be completed, and the builders faced a host of obstacles, the dome being the largest. After a century of building the new cathedral, the dome became the most remarkable architectural puzzle of the ages. [15] A contest was propositioned to find an architect builder to finish the dome. "Whoever desires to make any model or design for the vaulting of the main Dome…shall do so before the end of the month of September [1914]."[16]

Of the many plans submitted, only one proposal showed some promise—a model which presented a magnificent, bold, and unconventional answer to the problem of vaulting a large space—Brunelleschi's design. His radical design was to build two domes, one inside the other using a double-walled system from lightweight bricks laid in a herringbone pattern (1.2.2.2). Brunelleschi's solutions were ingenious. The spreading problem was solved by a set of four internal horizontal stone and iron chains, serving as barrel hoops, embedded within the inner dome: one at the top, one at the bottom, with the remaining two evenly spaced between them. A fifth chain, made of wood, was placed between the first and second of the stone chains. Since the dome was octagonal rather than round, a simple chain, squeezing the dome like a barrel hoop, would have put all its pressure on the eight corners of the dome. The chains needed to be rigid octagons, stiff enough to hold their shape to not deform the dome as they had it together.[17]

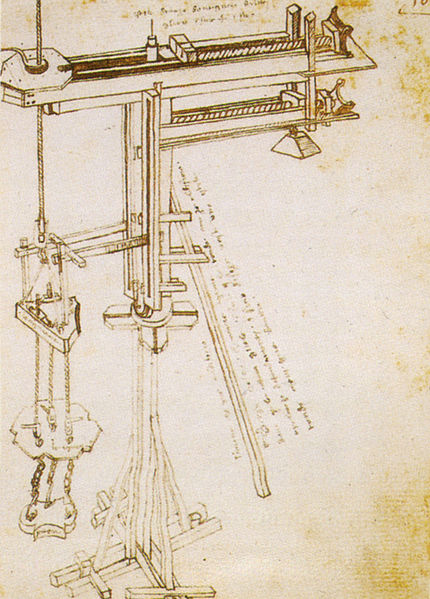

Many newly created machines were invented to hoist up the materials, including the thousands of 772 kg sandstone beams. The Castello (1.2.2.3), a crane with a wooden mast in the center and horizontal crossbeams, was controlled with screws and counterweights. It had three speeds and was also reversible, saving countless time and money.

The dome, 43.2 meters high, used precise mathematical measurements to lay the brick and sandstones. It continued spiraling upwards, adding support while the weight was shifted outwards to the dome supports. Brunelleschi had to design, create, and use numerous hoisting machines to lift the materials to the workers. The dome was a mathematical and architectural wonder, and visitors can still climb the lantern for magnificent views of Florence.

Brunelleschi was the first person in Europe to receive a patent for the design and implementation of a lift system used to haul brick, stone, mortar, and tools up to the great heights of the dome. The work started in 1420 and was completed sixteen years later to become the first dome built without a temporary wooden structure.

Donato di Niccolo di Betto

Donato di Niccolo di Betto (aka Donatello) (1386-1466), was born in Florence, the center of the new renaissance movement, and one of the original Early Renaissance artists. Studying classical sculpture in Rome, he created some of the most iconic freestanding male nudes, the first since antiquity. Donatello worked in many mediums, including bronze, clay, wax, and stone, and developed a way to carve in bas relief as many of his commissions were large architectural reliefs.

The Saint of Louis of Toulouse (1.2.2.4) is one of Donatello's earliest surviving bronze sculptures located in the refectory of the Museo di Santa Croce in Florence. The sculpture characterizes the Franciscan saint in his youth, draped in heavy clothing to signify his wealth. Donatello used the lost wax method of casting the complex bronze. Cast in eleven different pieces, it was hollow on the inside, including the back of the statue. The rich golden bronze carries a crozier as a gesture of blessing as if he was addressing the people of Florence. Some scholars believe the figure had a gilding process that covered the piece in thin gold and mercury to give it a sheen similar to gold.

Conceived entirely in the round, Donatello's David (1.2.2.5) was created in the traditional stance of a freestanding sculpture. It was one of the first since the Greek and Roman statues of the ancient past, making this statue revolutionary and exciting to view. The relaxed contrapposto stance of the tall, lithe body of the young David is resting on one leg and his sword, leaving the other leg to bend forward over the head of Goliath. David has an enchanting smile; his hands are by his side against smooth polished skin, and his long curly locks flow from underneath his helmet. The provocative statue stood on a column in the middle of the Medici Palazzo courtyard instead of the town square, indicating it may have been controversial to display a nude male figure at this time in the 15th century. Donatello was undoubtedly ahead of his time as an artist, leading the Renaissance revolution of acceptance and humanistic qualities in art.

Jan van Eyck

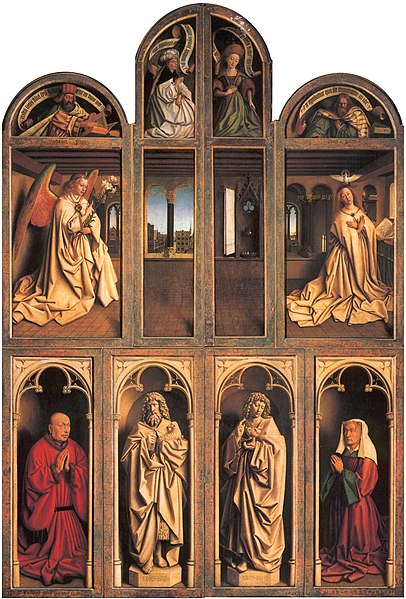

Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) was a Northern Renaissance painter from Bruges and an early inventor of oil painting. In the early 1420s, van Eyck became the painter to the Duke of Burgundy, producing both religious and secular work. In 1432, van Eyck and his brother Hubert van Eyck began building and painting a monumental polyptych called The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, better known today as the Ghent Altarpiece (1.2.2.6). The work consists of 24 separate painted panels on both sides and hinged together to be opened or closed to tell a story. The 3.35-meter closed altarpiece depicts the central panels painted like a chapel, the windows overlooking the town of Ghent.

Organized in two vertical rows, the closed altarpiece portrays the annunciation scattered with religious iconographies, such as the white dove above Mary's head representing the Holy Spirit. Upon opening the altarpiece (1.2.2.7), it explodes with color—God dressed in a red velvet gown surrounded by a gold throne. Mary dressed in a blue velvet gown and Saint John the Baptist in rich green clothing sitting next to God. Flanking Mary and John is the choir, complete with an ornately carved organ. In full nudity, Adam and Eve are on the two outside panels revealing their vulnerability.

The lower panels are divided into five sections centering on the Lamb of God in a meadow surrounded by angels and earthly prophets, apostles, and other church people near the fountain of life in the foreground. Unlike the top panes, the lower panels are set outside and spread over all five panels. The outdoor scene displays a beautiful green countryside with a blue sky and wispy clouds anchored by the sun in the direct middle of the panels. The attention to detail and clarity are generally unimportant; however, the van Eyck's were miniaturists and knew how vital finite details were in a painting. A significant innovation is the unique use of lighting using transparent layers of glazes. The panels contain subtle lighting shadows as an illusion of a well light cathedral; however, the dramatic lighting standing out in the candle-lit space.

Johannes Gensfleisch Zur Laden zum Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch Zur Laden zum Gutenberg (1398-1468) in 1436, invented the movable type printing (1.2.2.8) press in Europe. An inventor, craftsman, blacksmith, and publisher, he was well educated and from a wealthy family. Books during the 14th century Europe were each unique, monks in monasteries copying each one by hand. Gutenberg saw an opportunity when libraries were first opened, and scholars wanted access to many copies of the same books. Gutenberg started experimenting with text, cutting it up into individual letters, gluing them to small blocks of wood to use as stamps, each block inked individually. Then he invented metal text and a letter block mold, so all text was equal in size, giving typesetters the ability to form lines or pages of print. The form was inked and pressed by hand on paper. Gutenberg used a design similar to wine or apple presses with a screw design for pressure.

Although Gutenberg is credited in most textbooks with the invention of the moveable type press, in 1040 CE, Bi Sheng in China invented moveable type using porcelain.[18] During the Northern Song Dynasty, significant technological advances occurred, and paper money was first printed with copper metal type. Earlier the Chinese invented other printed methods. The first dated (868 CE) printed book (1.2.2.9) focused on the Buddha and his nine disciples in the imperial court where he is teaching about the illusory nature of all phenomena, including "self."

Gutenberg and his staff worked printing the Bible in black text for two years, illuminated by hand with colored inks. The first edition of 180 identical books was highly successful and began the printing revolution. Two years after Gutenberg invented the press, book production increased, and illiteracy fell. Although a printing press was invented in China and Korea a few centuries earlier, the technology had not migrated to Europe. Gutenberg's printing press is regarded as one of the most critical inventions in European history.

Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone (aka Masaccio)

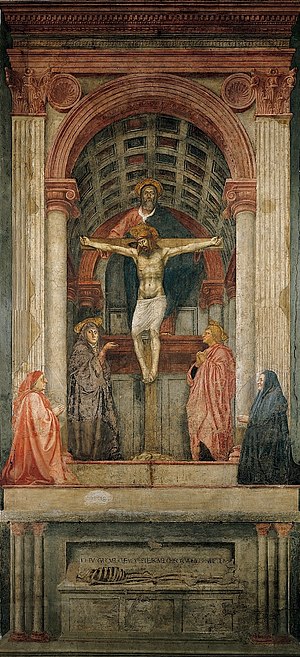

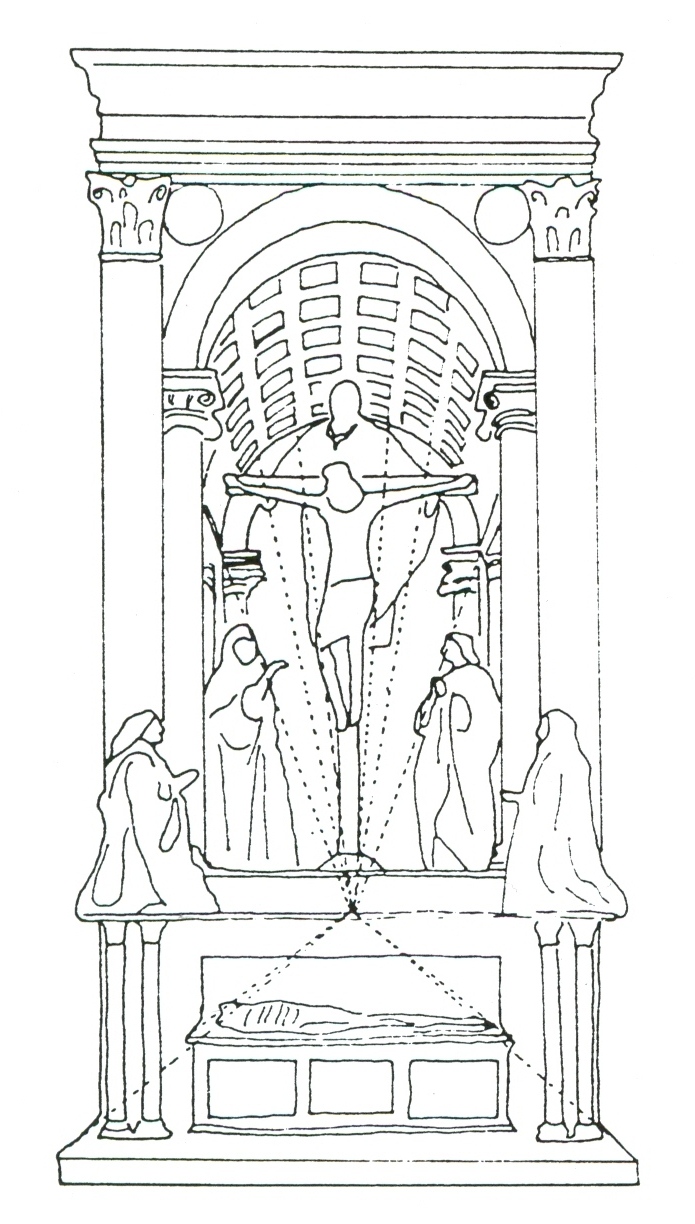

Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone (aka Masaccio) (1401-1428) was one of the best painters of the quattrocento period of the Renaissance. During his short tenure as a painter, he profoundly influenced other artists and their methods of using perspective, changing Western painting forever. Masaccio painted free from Gothic period designs and has been described as a painter of truth; unfortunately, he died at the young age of twenty-six. Moving away from the traditional, flatter Gothic style, Masaccio used perspective (Latin to "see-through") in his painting, a departure from standard painting methods. His use of a linear one-point perspective changed painting and drawing forever. The Trinity (1.2.2.10), located on the nave wall of Santa Maria Novella, was the first painting to follow Brunelleschi's new one-point system of perspective.[19]

The vanishing point (1.2.2.11) begins as a set of parallel lines like a train track, vanishing into the other side of the picture. The Roman triumphal arches in the Roman Forum may have been the inspiration for Masaccio's Trinity. His barrel vaults are drawn to the exact perspective shown by the coffered ceiling receding into the background. The realistic illusion of space creates depth with the use of the columns and ceiling. Christ on the cross is the center of the painting, the body painted in a muscular form looking down on Mary. The entire painting is located on top of an open tomb with the inscription: "As I am now, so you shall be. As you are now, so once was I". The incredible cavernous space shows the perspective point as right below the bottom of the cross. The significant advancements Masaccio used in this painting influenced the great artists of the Renaissance.

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filpepi (aka Sandro Botticelli)

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filpepi (aka Sandro Botticelli) (1445-1510) was an early Renaissance painter who attended the Florentine school under Lorenzo de Medici's sponsorship. Botticelli apprenticed at the age of fourteen to Fra Filippo Lippi and found himself in the middle of the golden age of Renaissance art. He became one of the most sought-after and esteemed artists in Italy during his lifetime. The Pope in Rome summoned Botticelli to paint the walls in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican. Using fresco as his medium, the walls started to come alive with the religious scenes.

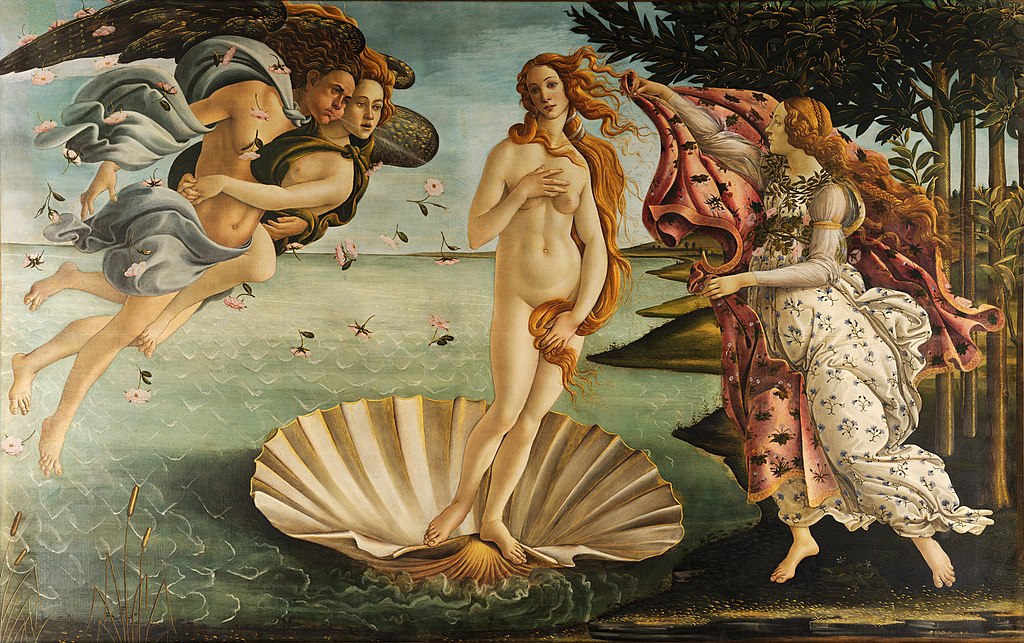

Botticelli returned to Florence in 1478 and began his most creative period of painting, producing the Birth of Venus (1.2.2.12) located in the Uffizi Museum. One of the most iconic paintings of the Renaissance. The painting is based on an ancient goddess of love, and a Greek statue de Medici had in his collection. Venus, born at sea, is standing on a seashell floating gracefully towards the shore with help from the God of Wind, Zephyr. As he blows her gently to the shore, flowers catch the wind in the air. Botticelli even included the white caps of gentle waves around the shell, and Venus is met by Hora, the God of Spring, with a flowing red robe covered in flowers against a land filled with trees.

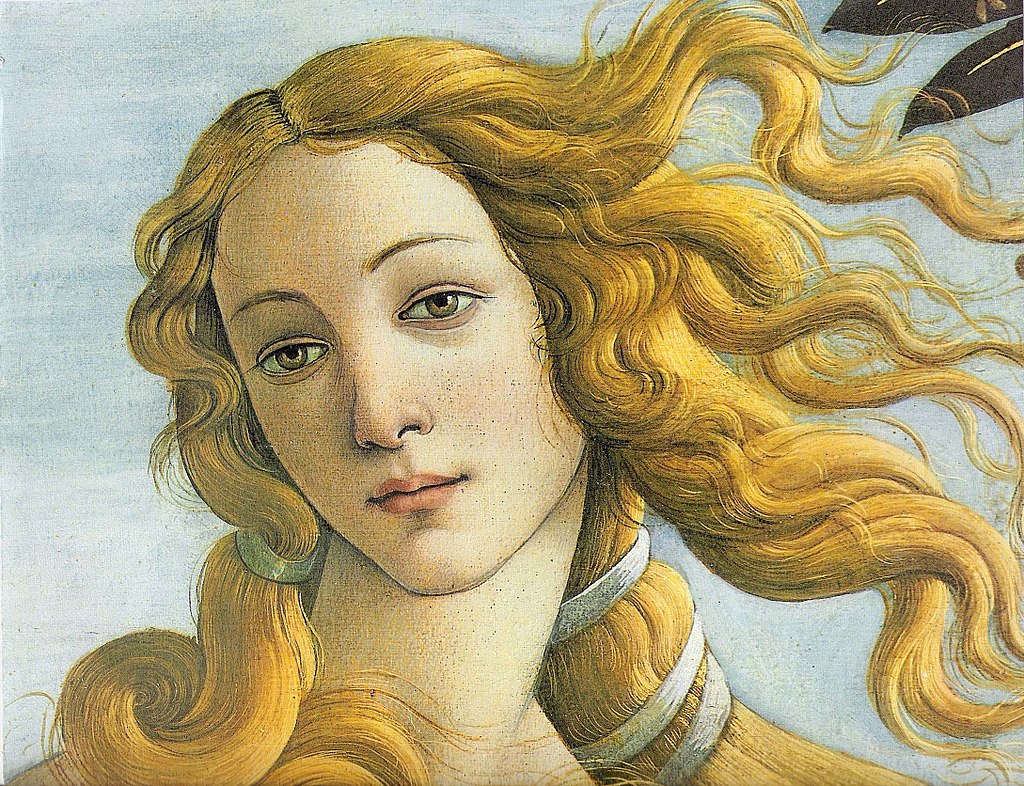

The background is unrealistic and does not have the depth seen in the Masaccio painting. An exciting illusion, the bodies not grounded on land, appearing floating, uncharacteristic for Renaissance artists. The sensual body and face (1.2.2.13) of Venus are painted in soft pastel colors and lack depth. Her face was melancholy, and her hair moved by the wind, all unusual thematic painting by Renaissance standards.

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (aka Leonardo da Vinci)

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (aka Leonardo da Vinci) (1452-1519) is one of the Renaissance's most famous polymaths, including painters, architects, scientists, mathematicians, astronomers, botanists, writers, engineers, inventors, musicians, and sculptors. Leonardo Da Vinci was born into a prominent Tuscan family and moved to Florence at seventeen to begin his art career. Leonardo joined the artist guild and soon flourished in the intellectual atmosphere. Da Vinci bounced around from patron to patron, painting, drawing, and designing. He drew anatomy from stolen corpses, learning how the body and brain worked and drawing elaborately detailed pictures of the elements of the human body, including a fetus in the womb. Leonardo had an insatiable curiosity for knowledge, which led to thousands of drawings in the sciences.

Leonardo Da Vinci left a large body of drawings of his scientific concepts for us to study. One can imagine Leonardo observing the natural world, looking at every detail, and thinking about every line. Before he even lifted a paintbrush, Leonardo completed a series of drawings, setting the stage for the actual painting. Leonardo only painted twenty-four pictures in his lifetime; however, he was a prolific illustrator and writer. His Italian script was written backward and can be easily read in front of a mirror.

Leonardo designed and engineered a wide variety of tools, machines, and other conceptual inventions. One of the most iconic drawings is the Vitruvian Man (1.2.2.14), drawn in 1492, with ink on paper, the man surrounded by a circle based on ideal human proportions. In Leonardo's journals, page after page describes drawings of flying machines, musical instruments, pumps, cannons, and many others. The central framework of the human-powered ornithopter shows a lightweight structure designed to enable a person to fly. Mechanical wings give the ornithopter its power for lift.

.jpg?revision=1)

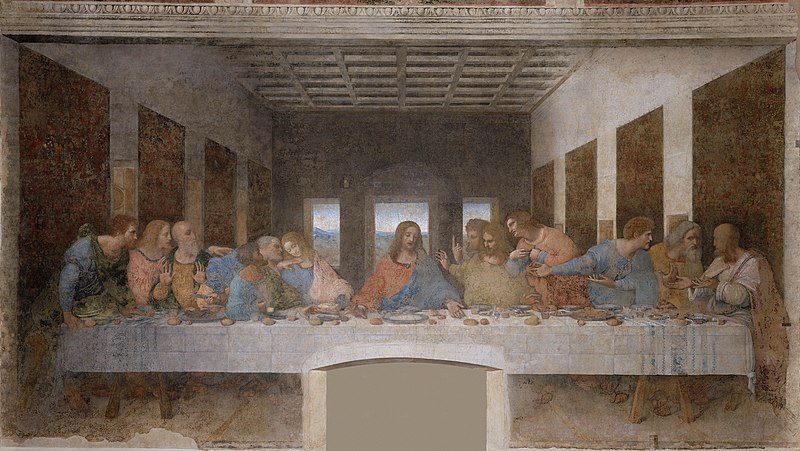

Perhaps the most famous work of da Vinci's career is the Last Supper (1.2.2.15) on the refectory wall in Milan's Monastery Maria delle Grazie. The fresco began to deteriorate in the early 16th century as da Vinci used tempera instead of paint while experimenting with different mediums. The stage-like setting hosts people eating behind a large table with white linen that dominates the scene. The perspective of the painting lands on Christ's right eye, emphasizing him as the central figure.[20] Each apostle is displayed in a static mode after being told about the betrayal; hands are raised, and some are getting up out of the chair in disbelief. Judas is standing behind the table with a bag of money.

Spanning many centuries, restoration has been an ongoing process for the Last Supper. Frescos are generally several layers of plaster, and then the paint is applied onto the wet surface to create a permanent bond on the wall. Da Vinci covered the wall with plaster and then a layer of lead white paint before painting with colors. The lead white is toxic and oxidized, turning a light brown color. In the late 20th century, a twenty-one-year restoration removed dirt, oils, and layers of shellac applied to stop the deterioration. The refectory was converted to a sealed room with a climate-controlled atmosphere to protect the Last Supper.

Another stunning painting, is the portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, the mistress of the Duke of Milan as the Lady with an Ermine (1.2.2.16). The small painting is on a walnut wood panel depicting Gallerani in half-height holding a pet ermine. She faces to the right with shoulders slightly turned to the left, looking beyond the boundaries of the canvas as she strokes the pet. The panel was painted with white gesso and then dark browns applied in the Sfumato method of layers of glazes. She seems to materialize from the dark background as the light shines on her delicate features and pet.

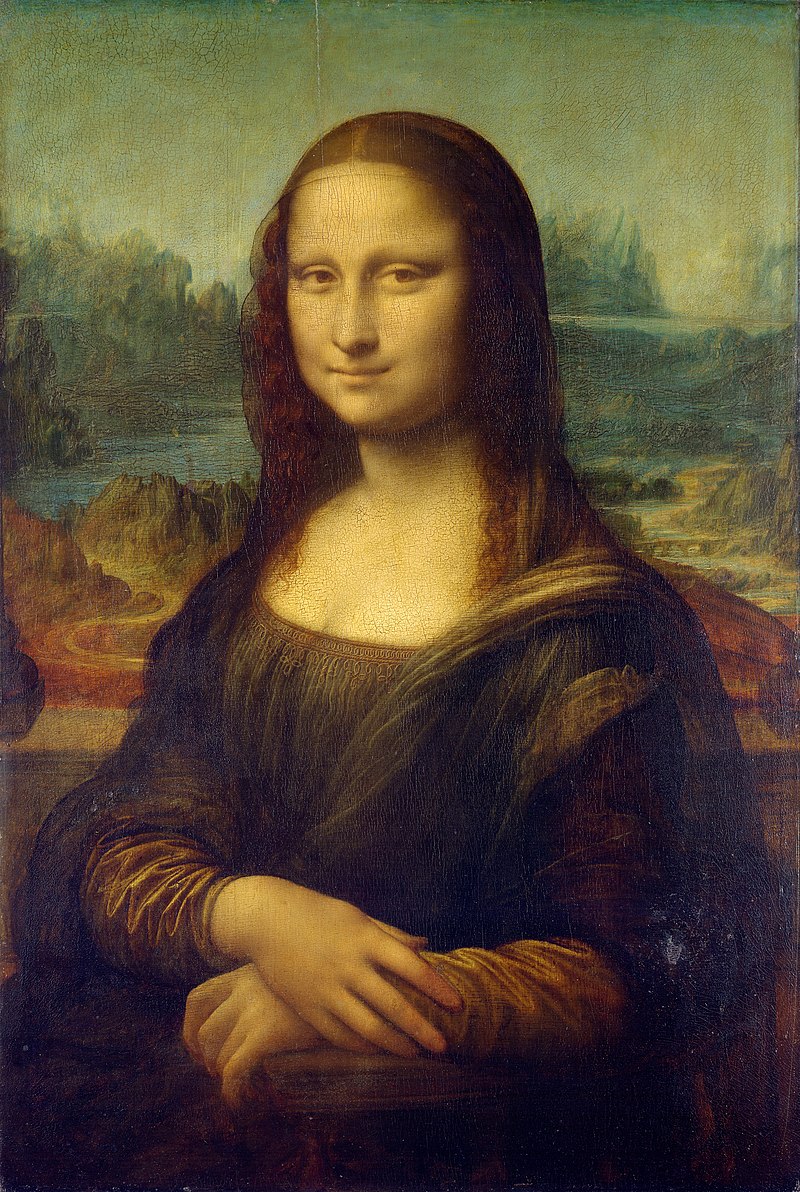

Leonardo's work still guides and inspires artists, philosophers, and scientists centuries after his death. The genius of Da Vinci's work and drive for knowledge places him at the top of the list of great artists of all time. The enigma of the Mona Lisa (1.2.2.17) remains one of Leonardo's mysteries. Everyone wants to know who she was, is it a disguised self-portrait, are their numbers painted in her eyes, are among the many theories about the painting. It was supposed to be a portrait of a cloth merchant's wife, a portrait Leonardo did not give to the merchant. The image is painted in half-length as she sits on a chair, dressed in unremarkable clothing. There is an appearance of a window behind her as she displays the emblematic smile. The complete wonder of the painting is what draws us into the painting.

Albrecht Durer

Albrecht Durer (1452-1519) was a German woodcarver, painter, and printmaker, who established a reputation across Europe when he was in his twenties. Durer created a vast body of work with classical motifs and religious portraits; one of his most famous engravings is Melencolia I (1.2.2.18), an allegorical composition with many iconic subjects. The engraving was completed in 1514 and included a carpenter's tools, a magic square, an hourglass showing time running out, a scale, a compass, and the despondent winged figure in the foreground with her head resting in her hand. Melencolia I is linked to astrology, theology, and philosophy, suggesting it is a self-portrait of the artist himself, perhaps an idea of the limitations of the earthbound realm and the inability to imagine advanced states of conceptual contemplation.

.jpg?revision=1)

Durer always believed he could achieve perfect proportions and measurements in his figures and painted his self-portrait (1.2.2.19) in early 1500 CE. Durer's position is straightforward and directly looks at the viewer with a somber face. Half-length and exceptionally symmetrical, he appears out of the dark background wearing a brown coat lined with fur, hand clasping the left edge. The intricately painted curls with golden highlights display the hairstyle of the times with a short, well-groomed beard. Rugged good looks add to the illusion demonstrating the exceptional talent of this young man.

.jpg?revision=1)

A study of wildflowers is one of Durer's realistic watercolor nature studies in Great Piece of Turf (1.2.2.20). Displaying a sizeable weedy patch of flowers still rooted into the soil was painted against a cream color background. The brownish-gray dirt reveals some of the roots in the foreground. It is highly detailed with the addition of a pen and inks. The elements in the three art pieces demonstrate a level of skill and his appreciation of details elevating Durer to a master artist.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (aka Michelangelo)

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (aka Michelangelo) (1475-1564) was born during the high Renaissance, one of the most famous artists as a sculptor, painter, architect, engineer, and poet. His unparalleled genius and artistic abilities and organic style brought marble to life, reflected in all the statues he created. One of his first major commissions was a statue of the Pieta (1.2.2.21) for one of the side altars in the church of Saint Peter's in Rome. The writer of the time stated, "No sculptor…could ever reach this level of design and grace, nor could he, even with handwork, ever finish, polish, and cut the marble as skillfully as Michelangelo did here, for in this statue all of the worth and power of sculpture is revealed." [21] The folds of her dress appear to cradle the lifeless body of Christ, a body sculpted in exquisite and sublime detail, his face gentle in death.

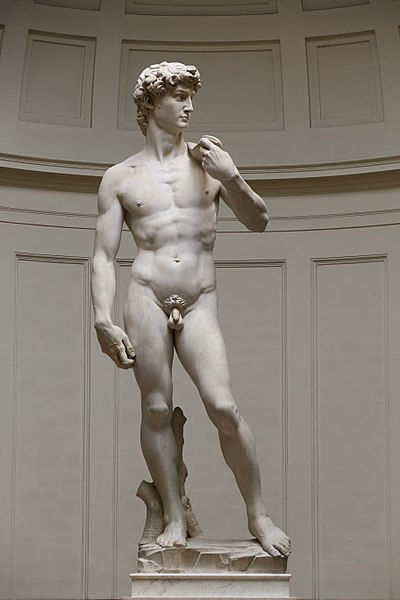

David (1.2.2.22), one of the most breathtaking masterpieces made of lustrous white Carrera marble, was Michelangelo's most massive sculpture, measuring 4.10 meters and exhibiting a perfect young man, muscular, contemplative, and ready for the fight. Generally, most artists portray David after the battle with Goliath, whose head lies on the ground. However, Michelangelo's David is caught in the tense pre-battle position.

The details Michelangelo carved (1.2.2.23) were far more advanced than other sculptors; on his hands, the tendons are visible under the skin, the veins running down his arm.

The look on David's face (1.2.2.24) is deep in thought of the upcoming battle, summoning the courage yet expressing the soft veil of fear.

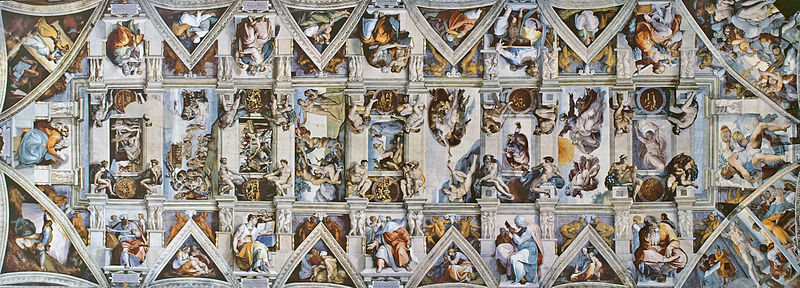

Michelangelo was also a great painter even though he thought painting should be left to others; however, he knew he had to paint the Sistine Chapel (1.2.2.25) ceiling or face the pope's wrath. The ceiling is over 20 meters high, and Michelangelo designed scaffolding to stand up under the curved ceiling and paint. He began the work in 1508, drawing figures and preparing the ceiling for the frescos.

The central ceiling consists of nine panels from the Book of Genesis, starting from the story of creation to Noah and the flood. The center panel is the iconic outstretched hand of God (1.2.2.26), giving life to Adam, whose finger extended to God but not quite touching, creating the magnetism between man and God.

.jpg?revision=1)

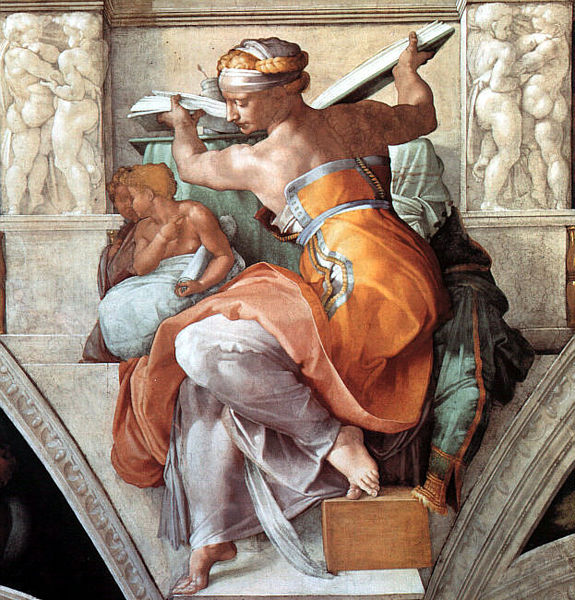

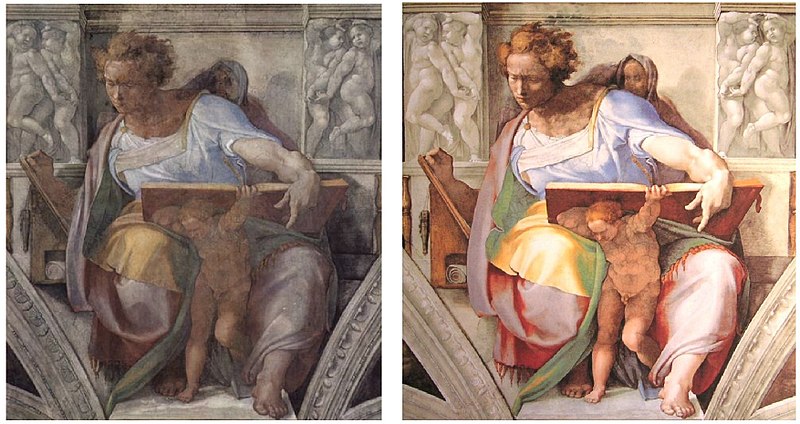

The Libyan Sibyl (1.2.2.27), with her Hellenistic features, is one of the most profound figures on the ceiling. Painted in her regal orange dress, she is lifting a large book off the shelf. The powerful arms and back are twisting the body, causing her clothes to fold as they flow around her legs, creating an illusion of tension.

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\): Libyan Sibyl, Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\): Libyan Sibyl, Public Domain

To paint the fresco style, Michelangelo covered a small section of the ceiling in plaster and then painted it into the wet plaster, which dried in a few days, revealing the final image. Over and over again, Michelangelo painted as he moved slowly down the ceiling, four long years on the scaffolding, with his neck craned upward until he completed the most iconic ceiling fresco in the world.

In 1979, restoration began in the Sistine Chapel to clean and repair the ceiling frescos and recondition them to their previous glory as first unveiled by Michelangelo. The restoration process started in 1980 to clean the soot and dirt of 500 years and repair cracks in the plaster, a long-involved process not completed until 1994. The image (1.2.2.28) of Daniel on the left side is how the image appeared after 500 years of dirt, and on the right is the result of the restoration process to reestablish the original beauty. The legacy of Michelangelo continues well past the Renaissance and he has continued to be remembered as one of the greatest artists of all time.

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (aka Raphael)

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (aka Raphael) (1483-1520) was an Italian painter living in Florence, a contemporary of Leonardo and Michelangelo. He was the son of a painter and was introduced to the humanistic philosophy of the times. Although he died at the early age of thirty-seven, he left a sizeable body of work. Raphael's most incredible legacy was the Stanze di Raffaello (1.2.2.29), located in the Apostolic Palace, next to the Sistine Chapel, where Michelangelo was simultaneously painting the chapel's ceiling. The library was a small room, and Raphael painted a different allegorical fresco on each wall representing the four branches of human knowledge: philosophy, theology, poetry, and justice.

Raphael's first painting on the east wall painted the famous School of Athens (1.2.2.30), portraying future knowledge. In the center of the painting, Aristotle in blue and brown and Plato in red and purple, holding their books, walking forward. In the left lower corner, Pythagoras is demonstrating the importance of mathematics. There are statues of ancient Greek gods on either side of the great-coffered ceilings linking antiquity with the Renaissance.

The second painting on the west wall, The Dispute (1.2.2.31), represents theology divided horizontally into earthly life and heavenly life. In the top half, Christ is depicted on a bench of clouds, surrounded by saints. The spiritual figures in the bottom half represent popes, priests, and church leaders, bringing together celestial knowledge through the divine host.

The third painting on the south wall, The Cardinal and Theological Virtues (1.2.2.32) illustrates the cardinal qualities as personified by three women: Fortitude, Prudence, and Temperance. Fortitude is holding a branch from an oak tree shaken by the cupid, Charity. Prudence looks into a mirror showing two faces with the cupid Hope holding a torch, and Temperance guards the cupid Faith.

.jpg?revision=1)

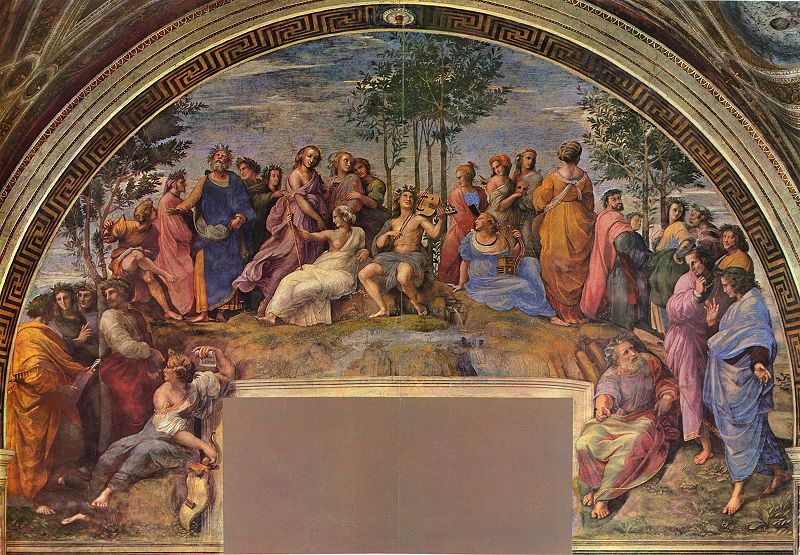

The fourth painting on the north wall, The Parnassus (1.2.2.33), illustrates the Mountain Parnassus where Apollo resides. Twenty-seven people from Greece flank Apollo in the center under a laurel tree, playing a musical instrument. The nine muses who portray art, nine poets from antiquity, and nine contemporary poets flank Apollo.

All four paintings together tell a story of the journey to the Renaissance period. The compositional harmony is apparent in all the frescos, and the visual counterpoint of the different groups of people creates a superior set of frescos. These frescos all demonstrate Raphael's unique and illustrative approach to painting.

Tiziano Vecelli (aka Titian)

Tiziano Vecelli (aka Titian) (1490-1576) was an Italian painter from a noble family who helped establish the Venetian art school during the Renaissance. Titian is well known for his dynamic use of color, rendering beautiful, realistic fabric in his paintings. Successful from an early age, his sizeable body of work spans decades and demonstrates the growth and maturity of his art.

The Assumption of the Virgin (1.2.2.34) was painted during Titian's high mastery period. The painting is exceptionally tall and one of Titian's largest altarpieces. Assisted by angels, Mary is moving from the earthly world into the heavenly world. The oversized figures on the bottom of the painting have outstretched hands trying to assist Mary on her ascent into heaven. The foreshortening of Mary is rendered exquisitely and looking up to the clouds, a halo of luminous golden light surrounds her. The unification of three separate scenes—heaven, earth, and the ascent—are individually challenging, yet Titian seamlessly paints all three together.

Hans Holbein the Younger

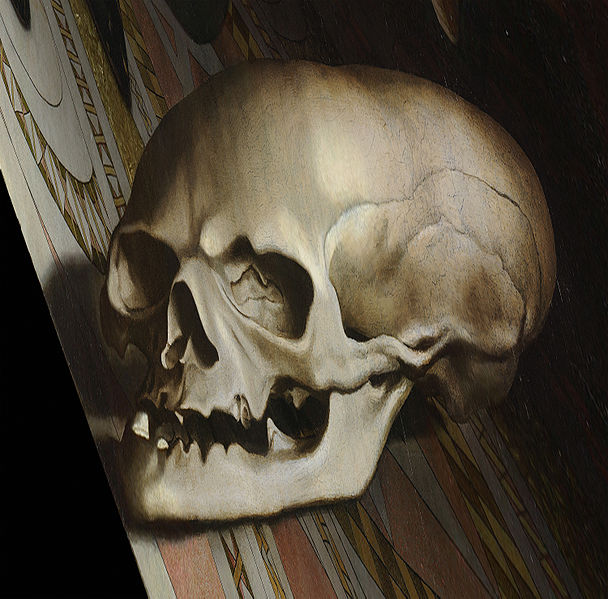

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543) was a Northern Renaissance painter and printmaker who worked mainly in Basel. In his younger days, he painted religious portraits, designed stained glass windows for churches, and printed books, becoming instrumental in changing how books were planned. Holbein could be called a realist as in The Ambassadors (1.2.2.35), a life-size panel with the Ambassador of Francis I of France standing with the Bishop of Lavaur. The two men are leaning on a high table with symbols and paradoxes, including an anamorphic skull. Among the icons is a selection of scientific instruments, including a shepherd's dial, a polyhedral sundial, a quadrant, two globes, and a torquetum.[22] Holbein also painted several textiles, including drapes, garments, and a rug on the top shelf. The floor mosaic may be from the floor design at Westminster Abbey. The two figures, one dressed in secular clothing (left) and the other in clerical clothes (right), implied a religious and scientific overtone. The lute, a musical instrument from the Renaissance, lies next to the open hymnal, suggesting opposition to change.

The most prominent feature in the painting is the anamorphic skull (1.2.2.36) in the foreground, an invention during this time. As one walked by the painting, the skull is seen in relative perspective, reminding us of mortality. It is interesting to note the mosaic floor becomes anamorphic when the skull is in view.

Holbein was employed as the King's Painter in 1537, painting the portrait of Edward VI (1.2.2.37) as a child, one of his most significant portraits. The future king was a mere two-year-old toddler, gripping a gold rattle while waving his other hand. Holbein "endows his sitters with a powerful physical presence which was increasingly held in check by the psychological reserve and elegance of surface appropriate to a court setting." Edward VI looked like a very young child yet was posed in a position with the severe demeanor of an adult as he stands behind a pulpit covered in fine velvet. The iconic portrait is draped with a mossy green-gray cloth for the background setting off the red and gold clothing of the young prince. Even the undershirt has been trimmed with gold at the neckline. Holbein establishes a technique for rendering the details of the dress, particularly noticeable in the silk sleeves and the intricate black scrolls. The portrait was a gift to King Edward V.

Jacopo Robusti (aka Tintoretto)

Jacopo Robusti (aka Tintoretto) (1518-1594), a Venetian artist, was one of the great Italian Mannerist painters of the Renaissance. Tintoretto attended the Venetian school of art and was influenced by Michelangelo, Vasari, and Giorgione when he painted (1.2.2.38) Gloria del Paradiso. Tintoretto's painting style is overly muscular figures, dramatic gestures, and his bold use of perspective.[23] His crowing piece of art, Paradiso, is a culmination of his life's work, the largest painting on canvas.

The painting overshadows the central gallery Doge's Palace in Venice and depicts a scene of religious heaven. The center of the painting portrays a radiant Archangel who opens the Empyrean heavens for the souls to ascend. Over 500 figures dominate the scene, focusing directly on Mary as Queen of Heaven and her son, Jesus. The two reigning figures are flanked by archangels, Michael handling the scales of justice and Gabriel bearing lilies.[24] The harmony of the celestial spheres sweeps in general arcs of holy figures across the wall, entitling the Doge of Venice to have the highest authority from heaven.

The Paradiso underwent a restoration in the 1980s, rolling the canvas and transporting it to a conservation laboratory. The cleaning of the painting lasted three years, and the beauty Tintoretto painted 500 years ago shows just as bright as then.

_Jacopo_Tintoretto_-_Gloria_del_Paradiso_-_Sala_del_Maggior_Consiglio.jpg?revision=1)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525–1569) was the most significant artist of the Northern Renaissance, painting a large genre of landscapes and peasant scenes. The work gives us a glimpse into the lives of regular people, unlike the religious portraits of kings we have seen to date. He traveled to Italy to study painting for three years and then lived in Antwerp for the rest of his short life. Antwerp presented Bruegel as an abundant resource for paintings, often in a landscape setting. He was a master of perspective and long-range views of many people and animals. The vivid depictions of village life included farming, harvesting, festivals, weddings, and other social characteristics of the 16th century.

The Wedding Dance (1.2.2.39) illustrates 125 wedding guests. During the 16th century, the bride, dancing with her father, wore black, and the men wore codpieces. The bright colors of the townspeople's best clothing unify the dancers on the mossy-green grass dance floor. The playful dancing symbolized fertility, although against the religious rules and regarded as a social evil and part of a series of the Seven Deadly Sins.[25] A colorful and realistic painting gives a glimpse into life in Antwerp.

The Harvester (1.2.2.40) is a genre of everyday life, and we are transported directly into a summertime day in the Netherlands. The landscape commences in the right foreground, with harvesters consuming the mid-day meal underneath the canopy of a tree while others are swinging the sickle. The perspective travels down the knoll out toward the sea in the far distance. The deep autumn yellow of the hay fills the lower half of the painting while the sky dominates the top one-third.

The Renaissance movement inspired artists to create in new ways using different methods, concepts, and materials. Linear perspective became important with receding parallel lines to create movement, an illusion of three-dimensional space on a piece of paper or painting. When he was designing the dome for the Duomo in Florence, Filippo Brunelleschi developed a methodology to draw his plans and demonstrate perspective. Michelangelo masterfully used foreshortening to create perspective by exaggerating the part of the object closer to the viewer. Michelangelo's David is an excellent example of how he used foreshortening.

The age of the Renaissance was one of the most critical periods in Europe for developing human awareness, individualism, and self-awareness, a bold contrast to the Middle Ages dominating Europe for centuries. The Renaissance started the conversation about science, art, mathematics, engineering, and cultural advancement. It was a period of the rejuvenation of antiquity, a time when innovation steered the art movement.

The Renaissance tolerated a minority of women to be apprenticed as accomplished artists. Women artists could accept commissions for their paintings when women were the property of their fathers or husband. Paintings discovered today are being credited to some well-known women artists, finally giving them the correct attribution. Overall, the Renaissance in Europe added realism as with Michelangelo's David, depth as with Masaccio's Trinity, emotion as in Suor Plautilla Nelli's Last Supper, all countless pieces of art we are providential to view today.

[14] Meek, H. (2010). Filippo Brunelleschi. Grove Art Online. Dio:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.,T011773.

[15] King, R. (2000). Brunelleschi’s Dome. (p. 5) Penguin Putman Publishing.

[16] King, R. (2000). Brunelleschi’s Dome. Cover. Penguin Putman Publishing.

[17] Ermengem, Kristiaan Van. "Duomo di Firenze, Florence". A View On Cities. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

[18] Needham, J. (1994). The shorter science and civilization in China. Cambridge University Press (4) (p. 14)

[19] Adams, L. (2001). Italian Renaissance Art. Westview Press. (p. 90).

[20] Zollner, F. (2000). Leonardo. Taschen Publishing. (p. 50).

[21] Vasari, G,.The Lives of the Artists, Oxford University Press; Reissue edition (2008), p. 424.

[22] Dekker, E. & Lippincott, K. (1999). The scientific instruments in Holbein's Ambassadors: A re-examination. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. The Warburg Institute. (62) (93–125).

[23] Zuffi, S. (2004). One thousand years of painting, Milan, Italy. Electa. (p. 427).

[24] Jacopo and Domenico Tintoretto’s Paradise at the Plazzo Ducale. Retrieved from: https://www.savevenice.org/project/j...retto-paradise

[25] Quist, R. (2004). The theme of music in Northern Renaissance banquet scenes. (p. 166).