1.2.1: Art Herstory- Women Artists in the Renaissance

- Page ID

- 128082

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Catherine de Vigri

Women have always been artists throughout time, it is the writers of history that have omitted women artists, from textbooks. Some scholars believe women were responsible for a large portion of the ancient cave art seen today. Art history was generally written by men in the 19th and 20th centuries and from a western perspective, overlooking women artists. Talented women succeeded in the Renaissance because they were nuns in a convent, a noblewoman whose families allowed them to paint, or they were born into a family of painters.

The town of Bologna in Italy was very progressive in the 16th century and had over 300 active professional artists—26 were women artists. One artist, Lavinia Fontana, is the first woman to rely solely on her commissions to support her family while her husband raised their eleven children. Unfortunately, this was the exception, and gender imbalances have limited women over thousands of years. History has valued male artists over female artists, and art previously attributed to male artists is now rightfully attributed to its rightful creative female artist. Prevailing stereotypes fit women into a "craft arts" category, and men are "fine artists" even though women are just as talented as their counterparts. The only way to re-write history is to include lost women artists.

Catherine de Vigri (1413 – 1463) is one of the best-known Italian early Renaissance convent painters of the 15th century. Vigri became a saint (Catherine of Bologna) on March 9th, a day in Italy when her achievements as a charismatic teacher, faithful nun, and devoted artist were recognized. She lived most of her life in Ferrara in the convent she founded. When she died n 1463, she was buried at the convent; however, an unusual smell emanated from her gravesite, and authorities exhumed her body. Believing it was a sure sign of holiness when her grave was incorrupt, she was canonized in 1526 and reburied.[5] Vigri began her art career by painting images on the wall of her convent and illustrated manuscripts. The manuscripts or prayer books contained about 500 pages, and Vigri illustrated approximately fifty images of Christ using the primary colors. The Madonna of the Peach (1.2.1.1) is a classic story about a hungry traveling family who was given peaches to eat. Gold stars flank the gold crowns and halos, and Mary is wearing her traditional red gown and blue overcoat. The baby Jesus is swaddled in a reddish-orange decorated blanket with a red cross around his neck. The white veil surrounding Mary's face and shoulders is also in the baby's grasp while Mary holds the iconic peach.

Properzia de Rossi

Properzia de Rossi (1490-1530) was an Italian sculptor from Bologna whose talent emerged at an early age. Because it was difficult for young girls to find any training except in managing a household, de Rossi learned to carve peach and apricot pits, an unusual material to use for anyone. The small sculptures were generally based on religious themes. After carving her intricate scene of the crucifixion on a peach pit, her talent acknowledged, and she received training in marble at the university. She acquired a commission for a bas-relief panel sculpting Joseph and Potiphar's Wife (1.2.1.2), displaying her talent to carve marble, a skill not well received by other artists who frequently discredited her. In the bas relief, Joseph is running from a bedroom to escape someone else's wife, a common theme in the early days of the Counter-Reformation. The classical marble relief demonstrates de Rossi's detailed and expert carving skills, one of her commission pieces.

Levina Teerlinc

Levina Teerlinc (1510–1576) was a North European Renaissance miniaturist painter and worked in the English court of Henry VIII. Born in Bruges, Flanders, Teerlinc was trained by her father (Simon Bening), a renowned miniaturist artist and illuminator. After marriage, she moved to England and went to work in the Tudor court as a painter. Attributing Teerlinc's work is challenging as she did not sign her work, and many were lost in a fire at Whitehall, Westminster. A 1983 exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum represented "the first occasion when a group of miniatures has been assembled which can be attributed to Levina Teerlinc."[6] The miniature painting A Royal Maundy (1.2.1.3) is a complicated scene of about 100 people in a tiny area. A religious service the day before Friday where a priest hands out small silver coins known as Maundy money (Queen's Maundy money), the details in this piece are precise and show dimension in the crowded room. Teerlinc painted the miniature Elizabeth I (1.2.1.4) when she was in the English court. The small image is exceptionally detailed, considering the tiny background she used.

Suor Plautilla Nelli

Suor Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588) was a Florentine painter whose nickname was "the nun artist" because of her spiritual attitude and religious paintings created while sequestered in the convent, Santa Caterinia da Siena in Florence. She was taught to draw and, over time, began an art studio with eight nuns. Some historians believe Nelli was one of the greatest artists despite her limited training and gender. She painted the Last Supper (1.2.1.5), which the Advancing Women Artists recently restored. Most art historians question the challenging work by Nelli since the composition and anatomy of the people in the painting place her work at the top of the Renaissance artists. They believe she would not have access to nude models.[7]

The Last Supper hung on a wall in a Florence Monastery until it was removed from the stretchers, rolled up, and stored in a warehouse for decades. "The Florentine nonprofit's all-woman team of curators, restorers, and scientists then began the arduous process of restoration, performing tasks including removing a thick layer of yellow varnish, treating flaking paint, and conducting an analysis of the pigments' chemical composition."[8]

Before starting the restoration, reflectography was used to determine any under drawings, and none gave the impression Nelli knew what she was undertaking. The work at the time needed a workshop of people and required scaffolding, and art assistants to finish the monumental work. The elaborate table was set with fine china, several glasses of wine, plates of bread, and a whole roasted lamb, typical food found in Florence in the 16th century.

.jpg?revision=1)

Catharina van Hemessen

Catharina van Hemessen (1528–1588) was a North European Renaissance painter and the earliest female artist with attribution to several small-scale portraits. She apprenticed in her father's studio, a well-known Mannerism painter. Besides portraits, van Hemessen painted religious figures with realism and depth of field. In Christ Carrying the Cross (1.2.1.7), Veronica is in the foreground carrying a picture of Christ on a cloth. The implied story depicts Christ as Veronica hands him a veil to wipe his forehead. When he returned the fabric to Veronica, his face was miraculously captured and known as Veronica's relic.[9]

The painting represents how Renaissance artists captured an audience. Van Hemessen also painted in the Mannerism style, as evident in Young Women Playing a Virginal (1.2.1.8). The portrait is thought to be her sister, Christina, a young woman in a dark dress against a very dark background. The golden headdress and face sharply contrast with the virginal, an early spinet with a keyboard and decorative scrolling on the side panels. The dark velvet dress presents a subtle pattern; the sleeves are highlighted with touches of yellow and orange. The young woman's delicate hands look as though they are captured in the middle of a song. Although a very gifted artist, van Hemessen had no surviving work after 1554 when she married, a common problem for young female artists.

Sofonisba Anguissola

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) was an Italian Renaissance painter born in Cremona and received a well-rounded education, including the arts. Anguissola possessed a gift for painting and was accepted into an apprenticeship to a master artist. She traveled to Rome, met Michelangelo and Milan, painted the Duke of Alba, and became an official court painter in Madrid. A letter written by her father described how fortunate she was to meet and perhaps studied, with Michelangelo. She painted over twelve self-portraits, a striking image for an artist of this period. In an early Self-portrait (1.2.1.9), she depicts herself painting the Madonna and child, although stopped in mid-stroke and looking as though she was interrupted.

Her later Self-portrait (1.2.1.10) was painted when she was seventy-eight, still a master of portraits.

Anguissola did not have access to male models and frequently used her family members to paint group portraits as a female artist. In The Chess Game, she painted her other siblings, Lucia, Minerva, and Elena (1.2.1.11). One sister looks outward, the subtle smile on her face seems to say, and I won the game. Anguissola's attention to detail involved changing textures of the brocade clothing, delicate laces, and perfectly braided hair. These family portraits and her self-portraits demonstrated her attention to elegance with the painted clothing. Her perfect painting of facial details helped Anguissola build her reputation.

When she was only twenty-six, she was invited to become a painter in the Spanish Court and spent several years creating official court paintings of royalty and other dignitaries. Using muted, darker colors, the official portrait of Phillip II of Spain (1.2.1.12) displays the delicate lace around his neck and perfect buttons on his gown, indicating her ability and successful career.

Lucia Anguissola

Lucia Anguissola (1536 or 1538 – 1565 to 1568) was the younger sister of Sofonisba Anguissola. Both received education in the humanities and arts and became painters. Unfortunately, Lucia died at the early age of thirty and did not have the opportunity to establish an extensive portfolio. The man in the painting is Pietro Manna, Physician from Cremona (1.2.1.13), believed to be a relative of the Anguissola family. He was painted with a limited palette of hues of brown and grey, a sense of personality on his face demonstrating Anguissola's capability as an artist. Anguissola depicted him sitting in the armchair, gazing outward at the viewer. He is holding the staff of Asclepius, the symbol of a physician.

Diana Scultori Ghisi

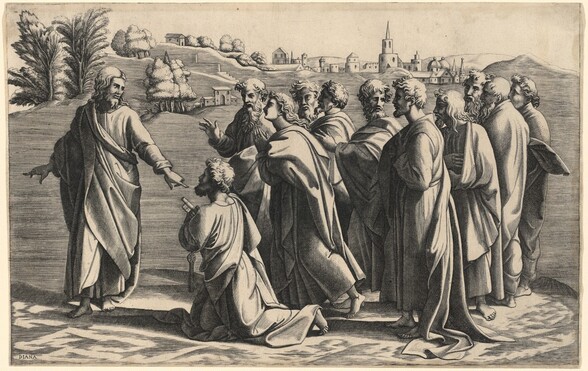

Diana Scultori Ghisi (1547–1612) was a high renaissance engraver from Mantua, Italy, and is credited with being the earliest documented women printmaker. Like many other women artists, her father was a sculptor and engraver (Giovanni Ghisi), and she worked in his studio from an early age. When she married an architect, they moved to Rome, and Ghisi received Papal Privilege to create and sell her work, an essential move in her career.

The changing climate and enlightening shifts during the Renaissance allowed women to follow their artistic dreams. Although many women followed in their father's footsteps in learning to paint, it was very uncommon for them to carve. In her print of Christ Making Saint Peter Head of the Church (1.2.1.14) may have been a drawing by Raphael. A popular genre, she exquisitely carved detail focused on Christ and Peter, a crowd to the right. A landscape of a small town is in the background, with fields in the midrange. Ghisi was the first woman to sign engravings permitting art historians to credit her thorough work.

Barbara Longhi

Barbara Longhi (1552-1638) was an Italian artist from the town of Ravenna and is the daughter of a Mannerist painter (Luca Longhi). Francesco Longhi and her brother (Francesco Longhi). She worked in their father's studio assisting on large altarpieces and became a respected portrait painter. Although little is known about her life, there are approximately 14 paintings attributed to Longhi. The painting Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1.2.1.15) is thought to be a self-portrait, the only one surviving.

Of Longhi's portrayal of herself as the aristocratic, cultured Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Irene Graziani writes; "when she exhibits an image of herself, Barbara, too, is presented according to the model of the virtuous, elegant and erudite woman, revisiting the themes which Lavinia [Fontana] had developed several years earlier in Bologna, according to a repertoire tied to late Mannerism".[10] The decidedly familiar Renaissance painting style is combined with the early Mannerism displaying a darker background illuminating the figure. The yellow blouse and light skin tones are accentuated against the brown background, and it is obvious the light source is coming from the left. Longhi's influences on art gave way to a long list of artists like Raphael and Anguissola inspiring up-and-coming artists.

Marietta Robusti

Marietta Robusti (1560-1590) was a Venetian painter and the daughter of the famous Venetian painter, Tintoretto, and she is occasionally referred to as la Tintoretto (little dyer girl). She lived in Venice her entire life and died at the age of 30 years during childbirth. At the time, women remained at home and were not welcome in the art world. Women painters were usually the decedents of painters and therefore had access to materials and learning from their fathers.

Self-portrait with a Spinet (1.2.1.16) is the only painting accurately attributed to Robusti. Painted in the tradition of contrast between light and dark, the three-quarter figure depicts a young woman with one hand lightly caressing a harpsichord behind her while the other hand holds a songbook. The slightly turned body wears a dress of white lace with a necklace of pearls, the head displaying a sideways glance, indicating the portrait was painted in front of a mirror. Although sometimes her portraits were considered stiff and unnatural, she had an eye for details and could realistically paint any jewelry or clothing.

In a time when women were legally their husband's property, required to take on the role of the typical housewife, focusing on her husband and children, Robusti was an accomplished artist and well sought after in her own right for commissions.

Fede Galizia

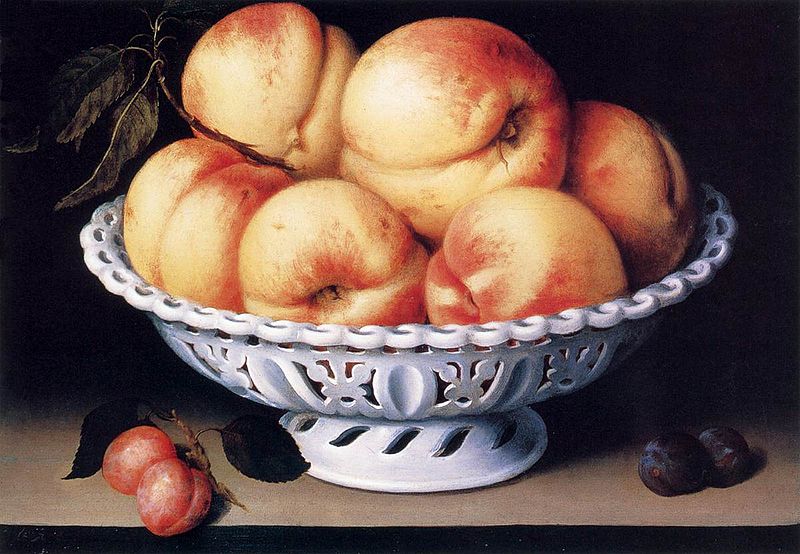

Fede Galizia (1578-1630) was another Italian Renaissance painter of portraits and still-life—a genre in which she was well known. Born in Milan, she was raised in her father's (Nunzio Galizia) art studio, where she learned to paint. By the age of twelve, Galizia was an accomplished commissioned artist with a recognized European reputation in her time. Although she painted many portraits, her primary interests lay in still-life. She pioneered the genre, and one of her most beautiful paintings is White Ceramic Bowl with Peaches and Red and Blue Plums (1.2.1.17). The detail on the canvas includes vibrant colors against the dark background, with leaves peeking out of the darkness, drawn to the light.

The term still life emerged in the late 16th century when artists moved away from religious compositions, free to experiment. Paintings could contain fruit, silver, found objects, plants, and animals (dead). At the time, there was an explosion of interest in anything found in the natural world as trade ships brought back specimens from around the world. The fruit was used to represent the nature of our existence as fresh and ripe, demonstrating abundance, vitality, and fertility.

Galizia's work was in the style of Mannerism and displayed intense attention to detail in every brushstroke. The still life was usually in a ceramic bowl or a straw basket piled high with seasonal fruit. Perfectly balanced, the fruit was exceptionally lifelike. The light and shadows contrast the delicate white ceramic bowl against the dark receding background giving the painting intense depth. One plum seems to almost tumble off the wooden table or countertop, a scene in anyone's kitchen.

Cherries in a Silver Compote with Crabapples (1.2.1.18) is still life on a stone ledge with a fritillary butterfly sitting on a crabapple leaf. The ornate silver compote holds the crabapples and is exquisitely painted with highlights from a light source to the left. The fruit appears from the darkness due to elegant stems with highlights matching the silver compote painted in light colors against a dark background. Of her surviving work—sixty-three in all—forty-four were still life, paintings emanating details of perfect fruit, picked ripe from the tree.

Elisabetta Sirani

Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) was an Italian Baroque printmaker and painter from Bologna, Italy, who helped establish an art academy for other women artists. She painted in swift motions with aggressive passion and produced more than 200 paintings and etchings in her brief career. After working with her father (Giovanni Sirani) in his studio, Sirani became one of the most renowned artists in Bologna, overshadowing her father. After her father's incapacitating illness, she became the family's primary breadwinner and supported them on commissions and fees from the studio.[11] Sirani was considered an excellent teacher and contributed to women artists' growth during the Renaissance.

Sirani had meticulous records of all her paintings, etchings, and drawings and signed most of her work, so attribution has not been difficult for art historians. Although many doubted she painted so many commissions, "Sirani's exceptional prodigiousness was the product of how quickly she painted. She painted so many works that many doubted that she painted them all herself. To refute such charges, she invited her accusers on May 13th, 1664, to watch her paint a portrait in one sitting".[12] Self-Portrait as Allegory of Painting (1.2.1.19) is a dramatic late Renaissance and just one of many examples of Sirani and her technical bravura and artistic virtuosity with expressive and broad brushwork, fluid impasto, rich coloring, and deep shadows.[13] Her paintings were considered "beyond women's capabilities," but Sirani was an artistic genius in reality.

[5] Arthur, K. (2020). Sister Caterina Vigri and “Drawing for Devotion”. (3). https://artherstory.net/sister-caterina-vigri-st-catherine-of-bologna-and-drawing-for-devotion/

[6] King, C. (1999). What women can make. (p. 61).

[7] Solly, M. (2019). Renaissance nun’s Last Supper painting makes public debut after 450 years in hiding. (10)

[8] Solly, M. (2019). Renaissance nun’s Last Supper painting makes public debut after 450 years in hiding. (10)

[9] Archaeological Intelligence". Archaeological Journal. 7 (1): 413–415. 1850. doi:10.1080/00665983.1850.10850808. ISSN 0066-5983.

[10] Ceroni, Nadia (2007). "Barbara Longhi". In National Museum of Women in the Arts (ed.). Italian Women Artists from Renaissance to Baroque. Milan, Italy: Skira Editore S.p.A. ISBN 978-88-7624-919-8.

[11] Artist Profile: Elisabetta Sirani'. National Museum of Women in the Arts

[12] Heller, N. (1991). Women Artists: An illustrated history. Abbeville Press. (p. 33)

[13] Modesti, A. (2020). Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638-1665). https://artherstory.net/elisabetta-sirani/