1.2: Renaissance (1400-1550 CE)

- Page ID

- 120723

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Quattrocento (1400-1499)

Rinascita, Italian for "rebirth," a period marking the end of Europe's feudal systems and entering a new form of a cultural and political society built on commerce. The shift from the Middle Ages in Europe to the Renaissance was a revival act of the classical styles of Greek and Roman art, highlighting humanists' progression. Leaving medieval values behind, humanistic learning dominated philosophy and the sciences. Humanism was a mode of inquest and studied through education of influential philosophies from the past. However, it is difficult for historians to define; they have settled on "a middle of the road definition... the movement to recover, interpret, and assimilate the language, literature, learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome".[1]

Moving from the scholastic Middle Ages study of Latin, natural science, and mathematics, the Renaissance concentrated on the human instead of a higher being to resolve tribulations and rationalize knowledge. The Renaissance spread from Italy to other regions of the continent, creating an artistic, political, cultural, and economic Rinascita.

The beginning of the Renaissance is the Quattrocento (1400-1499), the Italian word for number 400, encompassed artists' innovative, creative styles. The quattrocento art centers leading the transition included the Republic of Florence, Papal States, Milan, and Venice. Shedding decorative mosaics, illuminated manuscripts, and stained glass of the Gothic period, artists painted on wood panels and fresco walls using linear perspective to create realistic art.

Europe was in a cultural rebirth of art, and its development of linear perspective, Latin for "to see through," accelerated realistic aesthetics of painting. Linear perspective became important, using receding parallel lines to create movement and the illusion of three-dimensional space on a piece of paper or painting. Gone were the large gold halos, elongated figures, and static, flat holy people's painted bodies of the Gothic period. The Renaissance gave way to the beauty of nature, representing human forms by artists who were part of the vibrant culture of realism in paintings—Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Filippo Brunelleschi, Titian, Donatello, and Sandro Botticelli—all part of the rich culture of authenticity in paintings. The expanding trade along the Silk Road created an influx of money and an insatiable need for luxuries from the east.

Cinquecento

The Cinquecento (1500-1550) (five hundred) encompassed the high Renaissance, Mannerism, and early Baroque art styles. Giorgione and da Vinci's development of chiaroscuro and sfumato became the norm in painting, leading to dark and expressive paintings. The manipulation of light and dark created a bold contrast between the subject matter and the background, emphasizing essential areas. The High Renaissance was a short period yet profoundly influenced by the artist of the 15th century and paved the way for the new up and coming artists of the Mannerism movement. The High Renaissance was a period of enormous achievement and continuing political turmoil throughout Italy.[2]

The Influencers

In 1420, Pope Martin moved the papal seat back to Rome; although it had agricultural strength, it was not a commerce or banking center.[3] The Catholic church exploited art to lure 100,000 pilgrims during the Jubilee years, where "one could receive a full pardon for sins during a visit to Rome," [4] The pilgrims added to the church's revenues. To enhance the perception of Rome as the capital of Christendom required a massive undertaking to rebuild the Saint Peters Basilica, a relatively small non-descript building. Hiring architects, artists, and sculptures, the basilica was transformed into the most prominent church and is regarded as one of its greatest buildings.

Churches created the greatest need for art with a boom in the church building and the ultimate adornment of those buildings. The art was typological with the doctrine expressing the relationship between the Old and New Testaments. There was a resurgence in the devotion to the Virgin Mary, and art took on a hieratical appearance with Mary present in most art. A new way to create art for churches, and even small pieces for homes, was oil paint on panels, allowing artists to create small, realistic works. The churches required huge alter pieces with hinged panels that opened and closed, depending on the religious story the artist was portraying

A political dynasty, the Medici, was the most powerful family in Florence and influenced culture and art as their textile trade fortunes rose through the centuries. The family produced four Popes for the Catholic Church, which created an environment where art flourished. One of the Medici families' most outstanding achievements was sponsoring art and architecture and patrons for Brunelleschi, Michelangelo, and da Vinci. It was a conscious effort by the Medici to adorn the city of Florence in public art, not only for the patrons but for the good of tourism and economic growth.

Cosimo de’Medici founded the Accademia dell’Arte del Disegno (1.2.1) in 1563 and remains in operation today. The Academia was initially set up as a guild for artists and an academy for promoting and distributing the arts. Many famous artists such as Michelangelo, Vasari, and Gentileschi—the first women allowed into the academy. Following the unification of Italy in 1918, the school split into two different academies: Accademia dell Arti del Disegno and the Regia Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze in 1873, dividing into schools of architecture, sculpture, painting, and engraving. In 1978 the academy added the history of art and humanities.

The center of Italian art in France was the Academia du San Luca Fontainebleau School which first opened in the early 16th century during the Italian Wars. The Italian Renaissance had a profound impact on Europe, and art flourished throughout the continent. The aristocrats called famous Italian artists to their court to design and decorate the lavish castles. The Italian artists brought their knowledge of gold and silverwork, sculpture, stained glass, painting, and murals to wealthy homes in France. The rise of the Fontainebleau School was created under Henri IV's reign to decorate his residence at Fontainebleau, starting a new style of art that spread through Europe. The Ecouen Chateau houses the Renaissance Museum, representing the second Renaissance's emergence in France after 1527, classified as Italianism. The tromp l'oeil techniques are used in conjunction with a freshness of color, and graceful nudes creating harmonious compositions in the French courts. Inspired by classical mythology, the iconography of Italianism had a considerable influence on all art in France.

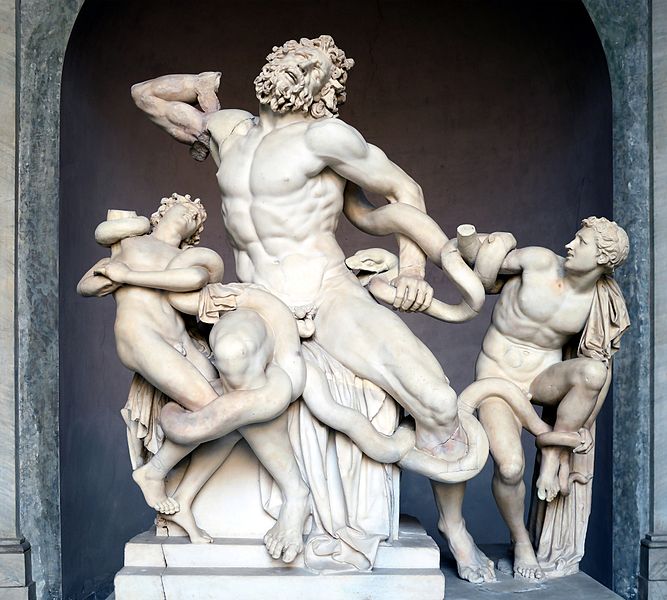

The Vatican Museum in Rome was created in 1506 with the purchase of Laocoon and His Sons (1.2.2) (a statue of the Trojan priest and his two sons), which was discovered in a vineyard in Rome. The statue was buried in dirt and only found when a vineyard worker was digging a hole. Today the museum houses over 70,000 pieces of art, including many Roman masterpieces. The Sistine Chapel ceiling and the Stanze di Raffaello are included in the museum acquisitions and have 54 galleries in total. The Vatican Museum was the first museum globally, set the standard for future museums, and now hosts over five million visitors yearly.

There was an extensive number of artists during the Renaissance period due to monetary support by families like the Medici and the Catholic Church. Economic wealth through trade routes around the world brought money into Europe and the coffers of the church and wealthy families. Artists flourished, workshops and educational opportunities grew, and artists were in demand.

[1] Burke, P. (1990). The spread of Italian humanism. The Impact of Humanism on Western Europe. Goodman and MacKay, London. (2)

[2] Adams, L. (2001). Italian Renaissance Art. Westview Press. (p. 291).

[3] Norris, M. (2007). “The Papacy during the Renaissance.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. (9). http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pape/hd_pape.htm.

[4] Ibid