1.3: Mannerism (1520 to 1590 CE)

- Page ID

- 120724

Mannerism

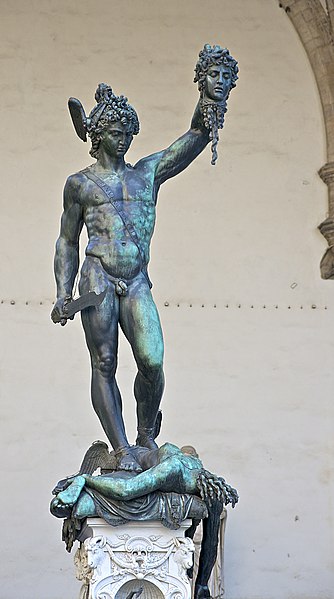

Maniera in Italian was a new style, Mannerism, moving from the classical versions of the Renaissance, bringing images less focused on the beauty of balance and perfect symmetry to elongated features with expressive and unusually positioned figures. Instead of an idealized and harmonious portrayal, Mannerism artists used dissonance, imbalance, and ambiguous figures. The style started in Florence and Rome and moved throughout Italy, a counter position to the formal style and idealism defined by the Renaissance artists and moved to unusual or contrived positioning in bizarre juxtapositions. Colors were placed in strange places using light to define exaggerated contrast. Some of the later Renaissance painters displayed Mannerism styles in Michelangelo's The Last Judgment with oddly muscled characters in tortured positions. The style of Mannerism was found in sculptures as well as paintings with complex poses and details.

Renaissance art was based on perfect proportions and symmetry, classical ideas of beauty. A painting in the Renaissance was grounded and centered, the figures arranged in perfect positions, almost idealized. Mannerism paintings were often off-center and focal points centered in unusual and unexpected places. Images were often unbalanced and dissonant, twisted or extended. A comparison of similar images of the Renaissance and Mannerism provides the contrast between the periods.

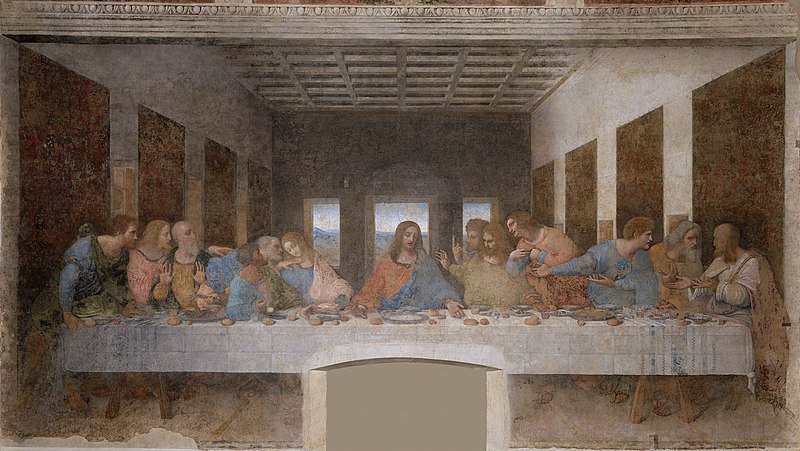

Both Da Vinci (1452–1519) and Tintoretto (ca. 1518–1594) painted the images of the Last Supper; Da Vinci (1.3.2) as a classical Renaissance painter, each figure placed in perfect positioning, the window providing the central position behind the Christ figure. Each side was balanced on horizontal and vertical planes. The colored robes moved across the center of the painting; only the prominent people in the story were portrayed. Tintoretto (1.3.1) painted in the style of Mannerism, the first notable difference is the number of people in the painting, including the angels flying across the top. The Christ figure has a light around him. Although he is placed in the middle of the painting, the figures on the left side are more prominent and appear to unbalance the center. The table is also set on a diagonal, moving the eye instead of the flat structured table in the Da Vinci version. The woman in the foreground with the large vessel has an exaggerated pose, appearing ready to throw the bowl. The figures in Tintoretto's painting appear in chaotic motion instead of flat, static, and predictable movement like Da Vinci. The light in Da Vinci's version comes from outside, while the light in Tintoretto's is unknown. The small gas lamp at the top illuminates upward; however, the table and the back of some figures have an unnatural light source.

The painting by Raphael (1483-1520) of The Entombment (1.3.3) displays the classical Renaissance proportions; each figure is perfectly sized and in position to help the Christ figure, or the saddened Mary, his mother. The scene focuses on every figure facing the subject they are assisting with the Christ figure diagonally across the painting. The light sky drops down, helping to center the images with five heads on each side of the painting. The colors of the figures and their clothing reflect the standard of the Renaissance period.

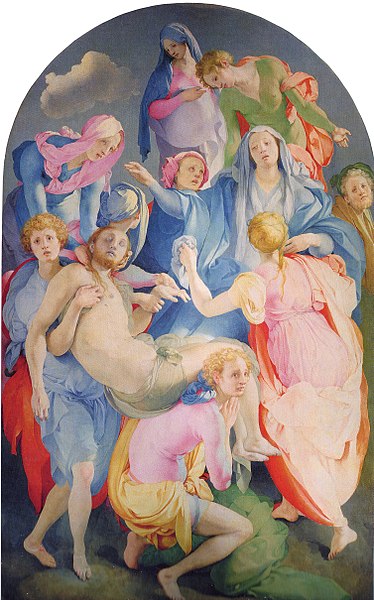

The painting of The Deposition from the Cross (1.3.4) by Pontormo (1494-1557) demonstrates the break from the previous standards; the figures are oddly positioned, and each looks at different events; even the Christ figure has an unusual position for someone deceased. The figures' heads are undersized with discordant positioning, overly long necks, or unusual proportions for their bodies. Pontormo used bright colors randomly, presenting no focal point, a swirl of pink and blue apparel throughout the painting with a green robe on the figure at the top and the odd yellow clothing with bright pink skin on the figure at the bottom. With the figures twisting in different positions, the Christ figure blends into the painting instead of becoming a focal point.

Raphael's Madonna Colonna (1.3.5) portrays the classical position of the idealized Renaissance Madonna looking lovingly at the child on her lap. The painting has the standard sky color behind the mother bringing the figures to the foreground with contrasting skin and clothing colors. Instead of distributing his figures in equal pairs on both sides of the Madonna, he crammed a jostling crowd of angels into a narrow corner and left the other side wide open to show the tall figure of the prophet, so reduced in size through the distance that he hardly reaches the Madonna's knee. There can be no doubt, then, that if this be madness there is method in it. The painter wanted to be unorthodox. He wanted to show that the classical solution of perfect harmony is not the only solution conceivable ... Parmigianino and all the artists of his time who deliberately sought to create something new and unexpected, even at the expense of the 'natural' beauty established by the great masters, were perhaps the first 'modern' artists.[1]

The painting by Parmigianino (1503-1540) of the Madonna with Long Neck (1.3.6) presents a different image; the colors are dark and moody, the child sitting on the lap of the Madonna has an elongated body and skin coloring resembling death. The Madonna has a long neck supporting a proportionally smaller head. Behind her is a small figure standing by a column, both unconventional images in the larger painting.

Rosso Fiorentino

One of the leading painters from Florence, Rosso Fiorentino (1495 – 1540), was instrumental in developing the expressive images found in Mannerism paintings, including his notable religious works. He went to Rome, Northern Italy, and France, where he influenced the French style and was one of the most-traveled painters of the time. His oversized work painted with oil on panel, Descent from the Cross (1.3.7), is an immense 375 cm high with eleven figures, all straining and twisting in grief. The Christ image blends in with the rest of the images, no longer the focal point as in most crucifixion paintings, only one of the figures involved to remove him from the cross.

In the upper part of the painting are the straining muscular men trying to determine how to remove the figure safely to the ground, all of them oddly balanced and slightly distorted in their efforts. "The light is not a normal illumination…: the scene is lit as if by lightning, and in the blinding flash the figures are frozen in their attitudes and even in their thoughts, while the great limp body of the dead Christ, livid green with reddish hair and beard, dangles perilously as his dead weight almost slips from the grasp of the men straining on the ladders."[2] The women on the ground await his Descent, demonstrating their sorrow. The painting is balanced through the middle with the cross and a ladder on each side and bright orange clothing on the figures at the top and bottom, making the feet of the Christ image balancing on the small platform appear to create the focal point.

Lavinia Fontana

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614) was considered a Bolognese Mannerist painter working in Bologna and Rome. She learned to paint from her father (Prospero Fontana), an art teacher at the School of Bologna. Fontana is regarded as the first female career artist in Western Europe as she relied on commissions for her income [3] while her husband raised their eleven children. She even had her husband sign a pre-nuptial stating she would continue painting and live in her family home. While her counterparts painted in court settings or convents, Fontana competed with male contemporaries on the open market, paving the way for other female artists.[4] She was considered the first woman who worked as an artist in the same manner as other major male artists, operating her studio, attending schools, working on commissions, and painting in various genres. It was common for female artists to paint portraits, especially of other females, and Fontana did many portraits. Still, she reached well beyond the standard practice and painted significant works with mythological or religious themes, even adding nude females, an unheard-of image for a woman painter. During her life, she had eleven children, earned a doctorate at the University of Bologna, was admitted to the academy, became famous, and was commissioned by the pope to paint images for his court.

Fontana painted roughly 110 paintings, including 23 altarpieces around Northern Italy. Supporting her family was a rare accomplishment; however, she had help from her hometown of Bologna. The town housed a liberalizing academy, an uncommon political organization, and diverse artistic patronage from the middle class, supporting women artists.[5] Bologna was more of a democratic city run by a diverse senate that wanted to patronize artists. Women had access to education at a university located in town, of which Fontana was an alumnus.

Fontana was well known for her detailed portraits of women, particularly successful painting lace and jewelry and the often-difficult images of hands. The subject of Lady with a Dog (1.3.8) is unknown; however, the focus of the painting was the display of the wealth and qualities of a good wife. She sits with her dog, a symbol of fidelity, and her elaborate and detailed clothing depicts a wealthy wife. Men were portrayed as statesmen, military leaders, or in other fields; a woman could only display her clothing as an accomplishment.

One of Fontana's unusual paintings was Portrait of the Gozzadini Family (1.3.9), a work commissioned by the woman in the red skirt. Although there are five people in the painting, two of the people, her deceased father and sister, were included in the portrait. The two figures standing were her husband and brother-in-law, the executors for her father's estate, an inheritance she hoped to obtain. Both women are wearing the exquisite clothing Fontana is known to paint with great detail. On the table is the requisite dog demonstrating the fidelity of the wife.

Christ with the Symbols of the Passion (1.3.10) displays Fontana's Mannerism style; twisted figures crowd around the oversized Christ. The influence of the recent Renaissance period is reflected in the landscape background, a specific part of a Renaissance painting. The sky is offset instead of in the center. The heads of each image are small and out of proportion with the bodies. The panel's painting is small, only and would generally be used for private devotion.

According to the Catholic Church, of the 23 altarpieces Fontana painted, the Assunzione della Vergine (1.3.11) is a classical scene of the ascension. An allegorical Virgin Mary rises between earth and heaven, ascending into God's hands dressed in the typical red gown and dark blue robes. The blue sky gives way to the glowing aura from heaven above while several Putti (angels) guide her up to paradise. Fontana moved to Rome at the invitation of Pope Clement VIII, and her career soared. She received numerous awards, honors and was elected to the Accademia di San Luca in Rome.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo

Although Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526-1593) painted the usual religious themes, his images of the human head formed from nature's bounty were popular with his contemporaries and are still well-known today. He was from Milan and became a court painter, originally following the tenets of the Renaissance until adopting the techniques of Mannerism. For the emperor Maximilian II, he painted the Four Seasons, pictures of heads in profile. Maximilian focused on science and created botanical gardens, growing unusual plants, subjects available to Arcimboldo to paint.

Anyone looking at Arcimboldo's composite heads for the first time feels surprised, startled, and bewildered; our gaze moves back and forth between the overall human form and the richness of individual details…Any transformation or manipulation of the human face attracts attention, but the effect is accentuated when we are confronted with monsters where, instead of eyes, mouths, noses, and cheeks, we find flowers or cherries, peas, and cucumbers, peaches, broken branches, and much else.[6] Winter (1.3.12) is believed to be the most expressive, with the gnarly trunk of a tree and broken limbs on the face. An orange and a lemon hang in front of his chest, one of the few fruits available in winter.