6.4: Gupta Period (320 CE – 550 CE)

- Page ID

- 219988

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Before the Gupta Empire started, other states and kingdoms in the region continued to fight each other for territory. When Chandragupta came to power, he expanded the army, and with his son Samudragupta, they conquered and united most of India. Chandragupta loved the arts and science and created an environment for the arts to flourish, even setting a precedent to pay artists. The Gupta Empire (6.4.1) became known for supporting the arts and creative innovation. During this period, the civilization was not wealthy or involved in extensive trade. However, leaders supported artists and scholars, allowing the arts to flourish.

Scholars wrote multiple forms of literature, including drama, poetry, reflective writings, and essays covering math, medicine, and other scientific fields. The different types of literature helped educate the people. The most famous essay was the Kamasutra, which defined the Hindu rules for love and marriage. The Kamasutrais still known today. Kalidasa wrote humorous, heroic plays, and the scientist Aryabhatta composed treaties on how the earth was round and moved on its axis around the sun. Aryabhatta also calculated the length of the year at 365 days 6 hours 12 minutes 30 seconds, remarkably close to the actual value, which is about 365 days 6 hours. Aryabhatta explained the lunar and solar eclipses and tried to calculate the earth's circumference as 24835 miles, only 0.2% smaller than the actual value of 24902—all of this centuries before Copernicus or Galileo.

Bhitargaon Temple

The Bhitargaon Temple (6.4.2) has survived from the Gupta period. Although some of the temple has been restored, it has many original parts and dates from the 5th century. The temple represents some of the Gupta's architectural innovations when building new Hindu shrines. The temple was designed in a perfect square of fifteen-by-fifteen feet internally with double-recessed corners and a tall pyramidal spire over the center. On the walls, terracotta panels depict images of Shiva, Vishnu, and aquatic monsters. The temple was damaged in the past, and some structures were rebuilt. However, the top was not repaired because no one knew the original shape.

Chess (Chaturanga)

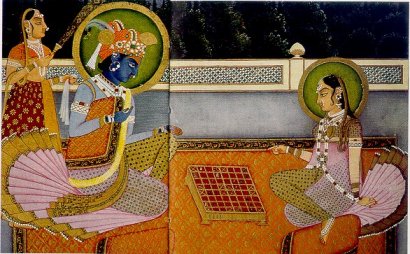

Chess is a strategic game made for two players using different styles of playing pieces that move according to prescribed possibilities. Chess has continued to maintain popularity today, with over 2,000 identifiable game variants.[4] Many historians believe the modern chess game derived from Chaturanga, which started in the Gupta period. The word Chaturanga means four divisions. The game used pieces depicting infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots. The game spread along the Silk Road and was documented in Persia in 600 CE. The image (6.4.3) depicts Krishna and Radha playing Chaturanga.

Mahabodhi Temple

The site at Bodh Gaya is understood to be the place of enlightenment, where the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama) sat under the Bodhi tree (6.4.4) and meditated. He renounced his life as a prince and decided to practice asceticism. In the 3rd century BCE, the emperor Asoka constructed the Mahabodhi Temple on the site where Buddha sat to meditate. The temple was demolished, rebuilt, and demolished again. During the 5th or 6thcentury, the final temple was reconstructed in the Gupta period. The Bodhi Tree, where Buddha attained enlightenment, is sacred. The tree was an oversized sacred fig tree (ficus religiosa) easily recognizable by the heart-shaped leaves. The original tree is not alive today; however, the tree by the temple is supposed to be a descendant of the original tree.

The Mahabodi Temple (6.4.5) is one of India's oldest surviving temples, and it is one of the four holy sites of Buddha. The temple is fifty meters high and part of a complex with the Bodhi Tree and the Lotus Pond. The temple is made of brick and influenced other brick architecture in India. Entrances to the temple are on the east and north sides. Honeysuckle and goose images decorate the entrances, and the entire temple has moldings with niches holding Buddha's images. Carved niches or openings above the moldings hold images of the Buddha (6.4.6). When a person looks at the temple, the niches resemble circular 'cow's eye windows.' The tower's top (6.4.7) is made with traditional features for Indian temples, with the stone disk ringed with ridges (amalaka) and a dome-shaped cupola topped with a crowned pot (kalasha). At the temple's corners are smaller shrines with towers on top. The chambers are sitting on a Buddhist relic mound. The temple's doorway faces east and leads to a hallway opening into the room with a gilded statue of the Buddha over 1.5 meters high. The view of Mahabodhi Temple today results from significant restoration in the late 19th century based on previous models and images.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=682&height=909)

Around the temple are pillars, railings, stones, and stupas following Buddha's pathway during his Enlightenment. The railings (6.4.8) were made from local limestone in the first century BCE, and most of the railings were replaced with granite railings in the seventh century CE. The railings were embellished with different figures. Small stupas are in front of the railing, usually used to hold the deceased's ashes and placed by the railings. Many of the original railings have been moved to a museum; those seen outside the temple are reconstructed copies. One (6.4.9) of the 3rd-century railing posts displays the Wheel of Law in the center panel. The wheel in the shape of a circle symbolizes the perfection of the Buddha's teachings, and the rim exemplifies concentration and mindfulness. The hub characterizes the wheel's moral discipline. The top panel portrays several chaityas and stupas, while columns with lion capitals flank the lower panel.

Learn about Bodh Gaya, one of several sights in India associated with the birth of Buddhism.

Sculptures

Most surviving sculptures were religious and carved from stone, wood, bronze, or terra cotta. Multiple religions thrived and were tolerated during the period, and their icons, gods, and other religious figures are reflected in most sculptures. Krishna in battle (6.4.10) against the horse demon represented Hindus, and the meditating Buddha (6.4.11) epitomized Buddhism. In this image, the figure poses his hands in a specific teaching gesture. Unlike earlier empires, sculptural work did not depict the ruling class. The Gupta Period peaked in 550 CE, leading to its final collapse in the 7th century.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=716&height=897)

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=739&height=946)

[2] Nalanda: The university that changed the world

[3] Ibid.