6.5: The Three Kingdoms of China 220 CE – 280 CE

- Page ID

- 232298

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Towards the end of the long-lasting Han dynasty, the country was plagued by continual battles, changing alliances, and weakening power, marking the end of the peaceful empire. The last known Han emperor was only eight years old when he inherited the throne and had no power, leaving an open power vacuum and forming three different kingdoms. When the Han nation was destroyed, three different sectors were created and entitled by historians as the Three Kingdoms (6.5.1). All three kingdoms were unstable, with continual wars against each other for power and territory, leading to ever-changing borders and alliances. The main three divisions were the Wei, Shu, and Wu, all names found in other states at different periods. Historians frequently added qualifiers to the names, calling them Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Dong Wu.

Out of this period came two battles of war now engrained in Chinese folklore and history. The battle of Guāndù was near the town, and "although Yuán had five times the troop strength of Cáo, he ultimately lost the battle because of indecisiveness and arrogant self-confidence, and the battle proved a turning point in Cáo's fortunes as he strengthened the expansionist state of Wèi. Storytellers stress the character flaws that led to Yuán Shào's military disaster when he should have had military success.[1] The battle of Red Cliff was based on Cao's forces coming from the south, his alliance with Shu, and the friction between the two, weakening them and leaving them in defeat. Throughout the Three Kingdoms, multiple strong personalities arose from the government and the military, creating larger-than-life stories for future Chinese writings.

The Three Kingdoms Period : The Great War for the Chinese Imperial Throne - Historical Curiosities

Inventions

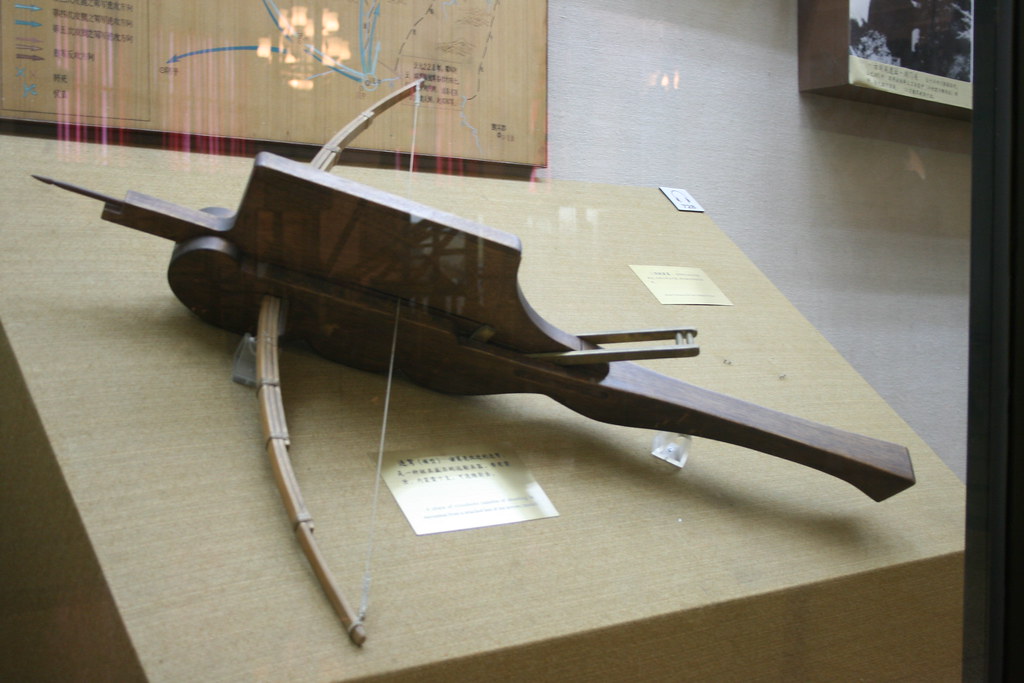

The Three Kingdoms period was filled with continual warfare, and fighting was enhanced with ongoing inventions. Current technologies were enriched, and new inventions became a significant part of the kingdom's economy, including new methods of warfare, agriculture, transportation, and even entertainment. One of the latest major inventions was the repeating crossbow (6.5.2). A series of bolts was added to feed arrows in the crossbow constantly. The movement was controlled by a lever to move forward or backward. Accuracy was not any better; however, with the constant stream of arrows shooting at the enemy, arrows were bound to hit something.

Traveling on the trade routes through unknown territories or moving armies to battle brought the difficult task of determining directions and where to go. The emperor commissioned Ma Jun to develop a device for installation on carts and carriages to detect where to go. Ma Jun designed a mechanism using gears always to point south. With the differential gears, the mechanism was rotated with the gears to point south. The figure always remained in its position until mechanically changed. The model of the device (6.5.3) demonstrates how the hand of the person stays pointed south, and when the carriage turns, the differential gears move, so the figure is always pointing south.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=735&height=699)

The Wei emperor also asked Ma Jun to improve how a puppet theatre operated because puppetry was a typical style of entertainment. "Certain persons offered to the emperor a theatre of puppets, which could be set up in various scenes, but all motionless. The emperor asked whether they could be made to move, and Ma Jun said that they could. The emperor asked whether it would be possible to make the whole thing more ingenious, and again, Ma Jun said yes and accepted the command to do it. He took a large piece of wood and fashioned it into the shape of a wheel, which rotated in a horizontal position by the power of unseen water. He furthermore arranged images of singing girls which played music and danced, and when (a particular) puppet came upon the scene, other wooden men beat drums and blew upon flutes. Ma Jun also made a mountain with wooden images dancing on balls, throwing swords about, hanging upside down on rope ladders, and generally behaving in an assured and easy manner. ..and all was continually changing and moving ingeniously with a hundred variations…"[2]

The emperor also asked Ma Jun to improve the pumps using chains to move water. The chains pulled the water up and diverted it through a channel. Ma Jun made square-pallet chain pumps to carry water to crops and create waterfalls and streams in public and private gardens.

The Mingyue Gorge erupts out of the fast-moving Jialing River with a 300-meter cliff. The region was mountainous with perpendicular cliffs and rushing water. Plank roads were constructed during the Qin dynasty and became a way to shortcut travel when transporting goods or for armies to send supplies to other parts of the country. Plank roads were also convenient weapons for one army to burn and prevent another from making easy progress. During the Three Kingdoms era, plank roads were extended and enhanced. Along the Mingyue Gorge, they installed a plank road (6.5.4) constructed straight out of the cliff. Holes were drilled in the rock, and horizontal beams were inserted to form the base. After the base was finished, the plank walkway was added. Plank roads throughout China were maintained, and some still exist today.

The wheelbarrow was inspired by a two-person handbarrow with a central wheel and a man front and back. By substituting a wheel for the frontman, only one person was needed to transport goods. The single-wheeled cart (6.5.5) was invented about 230 CE. The carts were more accessible to move and could follow the armies and transport their food and supplies. The wheelbarrow was called the wooden ox, and one person could carry food for four men. Today, the cart is a re-creation based on stone carvings. In the carving, the wheelbarrow is decorated with an imitation ox head.

When stirrups were invented in the 2nd or 3rd century, the idea became a significant advantage in combat, holding the rider in place while he fought. "The very earliest Chinese representation of a stirrup comes from a tomb figurine (x.x) from South China dating to AD 302, but this is a single stirrup that must have been used only for mounting the horse. The earliest figurine with two stirrups probably dates from about 322, and the first specimens of stirrups that can be dated precisely and confidently are from a southern Manchurian burial in 415. However, stirrups (6.5.6) have also been found in several other tombs in North China and Manchuria, most likely of fourth-century date. Most of these early Northeast Asian stirrups were oval and made from iron, sometimes solid and sometimes applied over a wooden core, and this form would remain in use for many centuries thereafter."[3] The stirrup was a way the cavalry could control the battlefield, and many historians believe it was one of the most impactful inventions in history.

Literature

Cao Cao (155-220 CE) rose to power as a de facto leader to position his son as the ruler. Cao Cao was a poet, and he became a chief influence in poetry, developing the Jian'an style of poetry and forever changing the style of poetry. This style of poetry focused on the transient nature of life for people and nature. One of Cao Cao's significant poems, Though the Tortoise Lives Long, defined the final certainty of life while praising how to live one's life well.

Though the Tortoise Lives Long

Though the tortoise blessed with magic powers lives long,

Its days have their allotted span;

Though winged serpents rid high on the mist,

They turn to dust and ashes at the last;

An old war-horse may be stabled,

Yet still it longs to gallop a thousand li;

And a noble-hearted man, though advanced in years

Never abandons his proud aspirations.

Man's span of life, whether long or short,

Depends not on Heaven alone;

One who eats well and keeps cheerful

Can live to a great old age.

And so, with joy in my heart,

I hum this song.[4]

Historians believe the manuscript, The Records of the Three Kingdoms, is a historical recounting of the end of the Han dynasty followed by the Three Kingdoms. A fragment from the original book (6.5.7) is a small part of the sixty-five volumes covering the Three Kingdoms. The volumes included each kingdom in the Book of Wei, the Book of Shu, and the Book of Wu. Information about leaders, important people, and events were recorded in the volumes. The author was Chen Shou, and he was assigned to write the history by the head of the Jin dynasty. The Records of the Three Kingdoms contained valuable information for other generations.

[1] Background to the Three Kingdoms.

[2] Needham, J. (1986). Science and Civilization in China, 4(2), 158.

[3] Graff, D. A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900. Warfare and History, 42.

[4] Though the Tortoise Lives Long