3.10: Murals (1920-1940)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174420

Introduction

Throughout history, large images on art-filled walls acted as a means of mass communication. Wall art has educated, manipulated, and recorded societies about religion, rulers, and historical activities. Rock walls of ancient caves are filled with symbols. Egyptian frescoes registered events of the kings. Renaissance frescoes illustrated religious beliefs. Chinese frescoes demonstrated the activities of the emperors. Early Aztec murals portrayed the lives of the gods. The Mexican muralists working in the early 20th century are frequently thought of as the dominant and preeminent mural painters since the Renaissance. Early Mayan and Aztec cultures of Mexico had adorned their buildings with murals for centuries. The new muralists brought the old art form to define their work, helping shape the history of post-revolutionary Mexico. The Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, overthrew the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. In 1921, Alvaro Obregon became President of Mexico and directed his education minister to develop a Mexican mural program and capture a national consciousness.

Before the Mexican Revolution ended in 1920, imported Spanish art was the typical style of most artists in Mexico. The new generation of artists after the revolution wanted to create a unique style of art for Mexico. The government supported young artists who began protesting the authoritarian regime and the lack of land reform. As David Siqueiros and Diego Rivera emerged as the prominent muralists, they were involved with the ideals of the Communists and helped teach peasants about their oppression and how to rise up. The muralists painted images based on current social issues. Rivera and Siqueiros believed art and politics were inseparable. José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, the three leading muralists known as Los Tres Grandes, emerged as the critical painters of Social Realism, an artistic movement functioning as a type of art, for and about the working and peasant classes of Mexico. The impact of the revolution was immense. Revolutionary murals by artists made an impact on the masses. Orozco, Diego, and Siqueiros became strongly associated with mural painting and sociopolitical art through their unique styles and are known throughout the world as the influences behind the Mexican Renaissance. It was the first time Mexican art made an impact on the history of art.

Politics was a popular theme for muralists based on workers, farmers, and soldiers. As the reputations of Siqueiros and Rivera grew, José Orozco became part of the group, all three impressing Americans who commissioned multiple mural projects, some of them controversial. Although each of the three artists shared similar political ideals, each demonstrated different artistic styles. Siqueiros frequently used an airbrush and synthetic paint that dried quickly and resisted weather extremes. Rivera painted with a smoother style and filled all the spaces of the canvases, creating stories. Orozco used broad brushstrokes in a more expressionist style.

In the United States, Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1932 during the depth of the depression and financial crisis. In implementing programs to help the nation recover, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was an important initiative. The WPA's mission was to construct buildings across America. However, art was included as a section of the program known as the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). Museum curator, Holger Cahill, was a friend of Roosevelt and one of the important people who believed art should be included in any plan as art was a product of our collective experiences.

Cahill said, "without the community's aid, [during the Depression] the arts would enter a dark age from which they might not recover for generations." [1]

The plan was a partnership between the projects and local artists through a series of murals to beautify buildings and create a feeling of pride in the community. The Mexican government offered artists commissions as early as the 1920s, giving the artists a source of income from private and public arenas. At the beginning of the Great Depression, American artists were still dependent on wealthy collectors or museums to sell artwork. Artists did not receive unemployment because they did not have regular jobs to lose; however, the works program manager told Roosevelt, "Hell, they've got to eat just like other people."[2] Government support of the arts during the depression was unique for the United States, a process to employ artists and decorative, educational artwork in public buildings. In 1934, the government hired over 3,500 artists for PWAP projects.

Mexican Murals

In 1920, after the revolution, the Mexican government commissioned multiple artists to produce murals, primarily to educate the mainly poor and illiterate people. With the Los Tres Grandes (Siqueiros, Rivera, and Orozco), a new style was developed known as Mexican muralism. They incorporated images of the past, including the Aztecs, the peasants who fought in the revolution, people representing the multiple Mexican races, as well as the ordinary working person. They created murals in public buildings, mainly immense fresco murals or mosaics. Many of the murals were based on the ideals of a different Mexico, free from Spanish rule and recognition of the mixed-race country, peasants, and the working man.

Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and his twin brother were born in Mexico, his brother dying when he was two years old. His parents were descendants of Spanish ancestors who immigrated to Mexico and were financially well off. Rivera started drawing on the walls of his house when he was three; his parents quickly installed chalkboards. He first studied at the academy in Mexico City before going to Madrid and Paris in 1907 to study art. Multiple artists inspired him, and different movements painted in Cubism and then Post-Impressionism. In Paris, he married Angelina Beloff and had a son who died early, simultaneously engaging in a partnership with Maria Vorobieff-Stebelska, who had his daughter. In 1922, he had returned to Mexico, divorcing Beloff and marrying Guadalupe Marin, with whom he had two daughters. He met Frida Kahlo, beginning a long affair until he divorced Marin to marry Kahlo in 1929. They both had different affairs with other people until they divorced in 1939, only to remarry in 1940. After Kahlo died, he married his agent, Emma Hurtako.

In 1920, the Mexican government started the mural program. Rivera became one of the artists. He was inspired by the political ideals of the Mexican Revolution and the Russian Revolution. Rivera wanted to create images reflecting the lives of the working class and Indigenous peoples of Mexico. He joined the Communist Party, whose ideals were frequently reflected in Rivera's art. Rivera developed a style focused on simplistic figures painted in bold colors for large fresco murals. He also incorporated symbols used in Aztec codices. In 1922, Rivera completed the first of the murals at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. In the Bolivar Auditorium, his painting Creation (5.10.1) demonstrates Rivera's approach to depicting the human form - its volume, weight, and geometric shape – reminiscent of Giotto's famous Padua Chapel paintings, as are the gold plate halos. Rivera used encaustic rather than traditional buon fresco to connect to pre-Columbian murals of the Maya and Aztecs. The work reflects racial equality, religion, and the importance of natural resources.

From 1922 to 1928, his works of over one hundred murals in the Secretariat of Public Education building in Mexico City, creating stories detailing the history and struggles of Mexico. Rivera liked the broad walls of the buildings, allowing him to paint grand designs accessible to the public, education of humanity's past and potential future. He viewed the public access to his murals as an antidote to the sterile elitism of the museum and gallery walls. He painted murals in multiple buildings throughout Mexico, incorporating revolutionary heroes, the working classes, ancient Aztec designs, the trials of the peasants, and the effects of technological progress and capitalism. Rivera stated;

"An artist is above all a human being, profoundly human to the core. If the artist can" feel everything that humanity feels if the artist isn't capable of loving until he forgets himself and sacrifices himself if necessary, if he won't put down his magic brush and head the fight against the oppressor, then he isn't a great artist." [3]

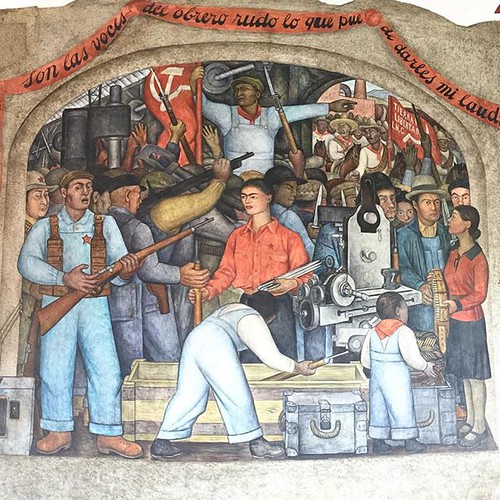

One of the frescoes at the Ministry of Public Education reflected the lives of the working class and Indigenous people of Mexico. The Arsenal (5.9.2) is nicknamed the "Distribution of Arms." Rivera continued to incorporate influences from Europe, but the subject matter related to Rivera's life and political ideas. The image reflected the red flag of the Communist Party with the symbol of the hammer and sickle. Frida Kahlo is in the center, and Rivera's friend, one-time lover, and fellow communist, Tina Modotti, held an ammunition belt.

Teotihuacan was the center of ancient Mexican culture. In the National Palace in Mexico City, Rivera painted the City of Tenochtitlan (5.9.3), starting with the conquest of the city by the Spanish until the beginning of 1935. The entire set of murals featured pre-Hispanic civilization to the conquest of the Spanish in one section and then the conquest forward to the future, each mural following a chronological narrative. In this mural, Rivera documents the city and how the people lived, demonstrating the sophistication of the immense city. Rivera frequently focused on historical events of the Spanish conquest and the effects on the indigenous populations. The painting demonstrates Rivera's concern with the pre-Columbian past. He painted the view of what Tenochtitlan's marketplace would have looked like in Aztec times. Rivera incorporated the Indigenous cultures and the mountains rimming the Valley of Mexico, juxtaposing the great city of Tenochtitlan in-between. Tenochtitlan was a bustling metropolis in the Aztec era with the Templo Mayor in the city's heart. The action of the Indigenous people in the foreground is the focus on Indigenous rituals and activities. Interestingly, today's National Palace overlooks the location of the original marketplace of Tenochtitlan and is situated next to where the Templo Mayor once stood.

Exploitation of Mexico by Spanish Conquistadors (5.9.4) is Rivera's mural in the National Palace depicting the brutality of the Spanish. In the background, the native people are hung from the trees and whipped into slavery. The more prominent Spanish figures also demonstrate their corruption. The martyrdom of the indigenous people became an essential part of the Mexican history and ethos, victims of the brutal European invasions. Both murals display his unique use of space, a style termed "agoraphobic," he did not leave any open space in his work. He also perfected the type of colors he wanted, turquoise blue framing the darker images.

One of Rivera's most ambitious projects was painting an epic narrative of the history of Mexico spanning three large walls within a grand stairwell at the National Palace in Mexico City, The History of Mexico - The World of Today and Tomorrow (5.9.5). Rivera employs his unique style and paints the story of the conflict between the Indigenous population and the colonizing Spaniards. Over a large expanse, the painted story starts with the legend of the return of Quetzalcoatl, ancient ceremonies performed by the Indigenous population. It also documents Spain's arrival and subsequent conquest of Mexico, including the fight for Mexico's independence.

Hombre en una Encrucijada (Man, Controller of the Universe) (5.9.6) was originally the mural Rivera painted in Rockefeller Center under the title Man at the Crossroads. This immensely controversial mural was destroyed. He painted this similar mural in the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes based on a black and white photograph of the original destroyed mural. The mural was based on the concepts of technological, scientific, and social changes in the world, the workman in the center of arcs of light representing discoveries rising from the telescope or microscope, the ellipses dividing the mural into sections depicting modern life. The headless statue of Caesar and Jupiter represented the overthrow of authoritarianism, freeing the workers. In the lower left-hand corner, Leon Trotsky is holding the red flag of the Fourth International along with Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx. At the same time, the view of Lenin sits nearby, images causing the controversy and destruction of the original mural in New York.

In the 1930s and 40s, Rivera painted several murals in the United States. In addition to painting, he mentored many artists, such as Bernard Zakheim, Victor Arnautoff, John Langley Howard, and Maxine Albro, who painted murals at the famous Coit Tower. Undoubtedly, Rivera, a legendary mentor, influenced their styles and the subject matter seen in the Coil Tower paintings. In Detroit, he was commissioned by Henry Ford to create a mural focusing on the workers in car factories, a controversial work and one of his most significant American paintings. The patron of his work at the Detroit Institute of Arts was Edsel Ford, Henry Ford's son. His work, Detroit Industry (5.9.7), appropriately involved themes of American industry, such as production, with a diverse group of men working with large machines. Rivera's socialist beliefs, controversial at the time, influenced his depiction of the diverse workforce all working together.

David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) was born in Chihuahua, Mexico; however, information about his early childhood was vague. His mother died when he was four, and he and his siblings were sent to live with his grandparents. Siqueiros went to Mexico City to study art as a teenager, becoming active in the new political concepts, leading student protests, and joining the post-revolutionary factions fighting for control. He also saw the plight of the people in the country and their poverty. In 1919, Siqueiros went to Paris to study, met Diego Rivera, and traveled in Italy to study the frescoes of the Renaissance. When Siqueiros was in Europe, he also went to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War and joined the Communist Party. Siqueiros went throughout the Americas to influence other artists with his ideology, believing art is for the people, not a privilege for the bourgeoisie, and mural painting was a significant art form for the people. Siqueiros wrote:

"The artist must paint as he would speak. I don't want people to speculate what I mean. I want them to understand."[4]

Siquieros' style can be considered Expressionistic, like that of Orozco. His intense use of the line and dynamic foreshortening created a work of motion far beyond his contemporaries. In the 1930s, Siqueiros did not use typical fresco techniques and experimented with different materials, including a form of quick-drying industrial paint applied with airbrushes and stencils. The Polytechnic Institute located in Mexico City developed a plastic style of paint specifically for Siqueiros. The paint dried rapidly, and he was able to apply several layers. His discovery of the technique was accidental when he poured diverse colors of paint on a wood panel. The colors spread and came together, some of them mixing. The infiltration of colors occurred from the different densities and viscosity of each color based on the compounds used to make a particular color. Although Siqueiros did not understand the dynamics of the process, he did understand how to use the concepts of flowing liquids in his painting.

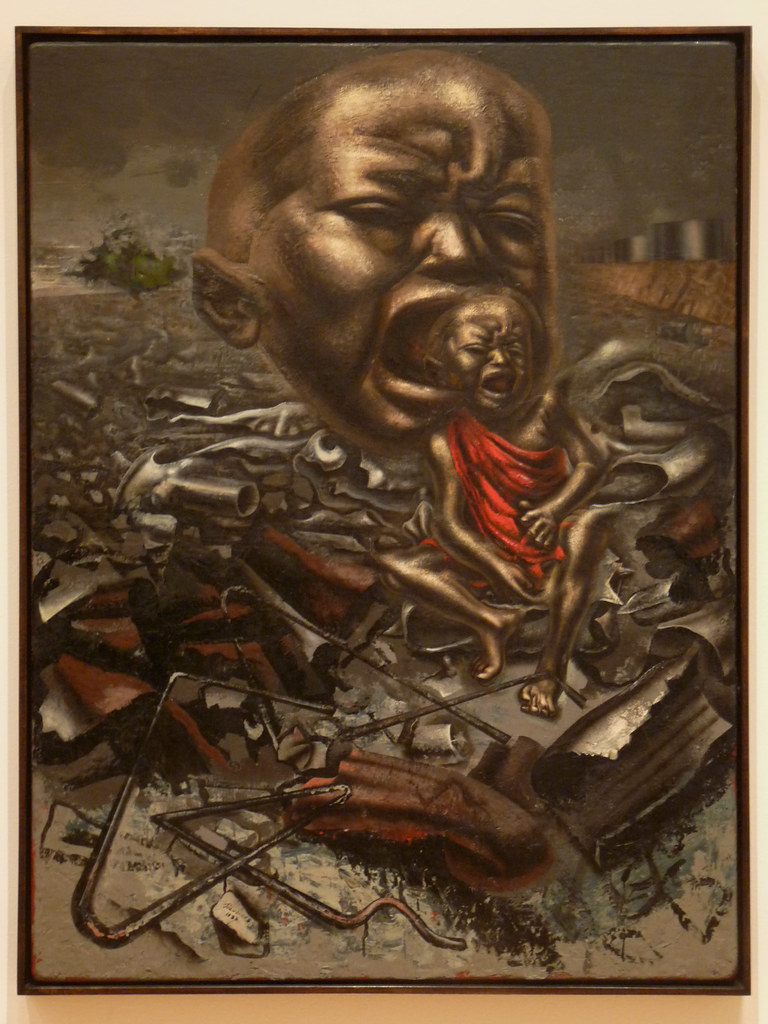

Siqueiros' paintings usually focused on the plight of humankind, and he developed a specific style to portray the human body, accentuating the angles of the body's joints. He also featured hands as a heroic symbol of the worker gaining strength. With the understanding of his time spent engaged in war, the painting Echo of a Scream (5.9.8) appears to be a war zone, covered in twisted metal and implements of warfare. Faces emerge, appearing to be babies screaming out. One pop of bright red color on a child's body contrasts with the overall brown-muted tones of the painting. The red garment acts like a slash across one's body from a distance, with blood seeping out.

In Cuauhtémoc Against the Myth (5.9.9), the vibrant colors create distorted forms in the violent scene. The images portray the battle of two allegorical characters. The Aztec Emperor, Cuauhtémoc, pierces the heart of the centaur. The centaur represents the imperialism of the Spanish and their Christian religion against the Aztec, the Spanish repelled by the revolutionary forces. The small figure of Moctezuma in the background signifies the victory of the revolutionaries.

Torment and Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc (5.9.10), located at the Museum of the Palace of Fine Arts, depicts the violence of the Spanish conquest. The Spanish soldiers are torturing the local leaders, trying to force them to state where the treasures of gold and silver were located. The female figure, representing the Mexican motherland, stretches out her arms to protect the prone figure of Cuauhtémoc, the praying companion kneeling beside him. The murals of Siqueiros helped re-tell the stories of lost history, inspiring the people and supporting the revolution.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Torment and Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc (1950-51) by kate CC BY-ND 2.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Torment and Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc (1950-51) by kate CC BY-ND 2.0The Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros is a 12-sided outside and octagonal inside structure with four interior levels used as a gallery, meeting, and concert rooms. The fourth floor is covered by the March of Humanity (5.9.11) mural. Twelve exterior murals, each covering 160 square meters, depict diverse themes, including the environment, dance, Christ, masses of people, and even acrobats. The mural is painted inside the forum, beginning with a dome opening and ending at a scene of nightfall. Giant hands symbolize man and the need to dominate, contra-posed with a woman who seeks peace on each end. The mural starts with violence and the infliction of suffering overlaid with the struggle for survival. The second part depicts the march toward a revolution based on science and technology and the optimism of the future. The end shows the possibility of a future free from repression and violence, freedom for the people.

Historically, the origin of Olvera Street has been deemed by many as the birthplace of Los Angeles. A woman named Christine Sterling wanted to turn what had become a dilapidated part of the city into an environment like a small Mexican village. She was successful, and the beginnings of the village began in 1930 when the street was closed to car traffic. In 1932, Siqueiros was invited to Los Angeles to teach about mural painting. He used some of his students to help with the mural America Tropical (5.9.12) painted outside the Italian Hall on Olvera Street. The mural depicts a crucified Mexican Indian, the American imperialist eagle hovering above him with extended talons. He believed the mural portrayed the destruction of the indigenous cultures in America by previous invaders and today's cultural inflictions. The subject matter of Siqueiros' mural was controversial. The struggle against powerful forces by the less fortunate offended the local business members. A year after the mural was completed, it was covered with white paint. Recently the mural has been uncovered and restored.

José Clemente Orozco

José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) was born in Mexico; his father encouraged him to study at an agricultural school in San Jacinto as a teenager. During this period, he had an accident with fireworks, damaging his eyes and losing all the fingers on his left hand. Orozco went to Mexico City and studied art, heavily influenced by the revolution unfolding around him. After art school, he worked as an illustrator for newspapers in Mexico City, married, and had three children. During the Mexican Revolution, Orozco set up a studio, depicted illustrations, and cartoons, and found work as a military correspondent. Orozco went to the United States because it was difficult to succeed as an artist during the social and political upheaval. Eventually, Orozco returned to Mexico and secured a mural commission. He became known as one of the leaders in Mexican mural art along with Rivera and Siqueiros. Orozco concentrated his art on the peasants' struggles, life's hardships, and the societal changes in post-revolutionary Mexico. Orozco was the most pessimistic of the Los Tres Grandes, and unlike Rivera, he took a darker perspective of the revolution, the bloodshed, and its toll on the people. Orozco always maintained compassion for the common person and focused on good and evil and the social compacts of governments and religions.

In the mural, The Trench (5.9.13), at San Ildefonso College in Mexico City, Orozco used dynamic, strong lines and a blood-red background. The revolutionary figures in the foreground form the shape of a cross and may reference sacrifice, specifically, Christ on the cross. He chose a more Expressionistic approach, aligned with European modernist to evoke the viewer's emotions instead of the idealized revolution and its heroes. In Mexico, Orozco's work was not well-received.

He went to the United States again in the 1930s and created a mural at Pomona College in Southern California, titled Prometheus (5.9.14). Orozco continued the use of dynamic lines, and the red-blood background of colors conveys an emotionalism. The main subject of Prometheus seemingly is taking fire (a source of knowledge) to give to the enlightened – shown on the left looking up at him. The figures on the right turn away, seemingly preoccupied with their worlds.

_de_Jose%25CC%2581_Clemente_Orozco_en_Pomona_College.jpg?revision=1)

Painted between 1932 and 1934, one of Orozco's most famous murals was at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, The Epic of American Civilization (5.9.15). The mural covers about 300 square meters made into 24 panels. Orozco portrayed the impact of invasion and revolution on Indigenous people, the horrors of war, and how violence and industrialization affected the human spirit. He was a pivotal artist to bring consciousness to art using murals. The murals were frescoes painted on the walls, progressing through time, starting with the first people to inhabit the earth.

The Departure of Quetzalcoatl (5.9.16) is part of the panels portraying Mexican history before the Spanish invaded. Quetzalcoatl, represented in human form, was a god who helped the people and drove off other gods. In this panel, those who followed the banished gods are forcing out Quetzalcoatl.

Gods of the Modern World (5.9.17) demonstrates institutional religion's indifference to the people and the social upheavals occurring around them. Orozco had the freedom to paint whatever themes he wanted, leading to some of the college parents' great displeasure. They requested the murals be destroyed because the parents believed they represented communism. The university stood firm, and its president wrote, "There are 100% Americans who have objected to the fact that we employed a Mexican to do this work, but I have never believed that art could be made either racial or national. As to the images not being 'nice,' if that be a criterion of judgment, many of the great works of the medieval masters would have to be removed from the Louvre."[5]

Orozco created a series of murals at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria at San Ildefonso College, covering three floors, including murals in the stairways. The theme of the murals was to reflect the struggles of the Revolution; however, political conflicts led him to stop working on the murals. When a new government came into power with different attitudes, he returned to finish the murals. La Trinidad (5.9.18) portrays one of the revolutionary leaders in the red hat threatening the peasants he is theoretically helping. The peasant in the gray pants on his knees is pleading for mercy while the peasant in the white pants, his hands severed, watches. The display demonstrated how those recruited to fight had no idea why they were fighting or who they were fighting.

Public Works of Art Project (PWAP)

The Public Works of Art Project was part of President Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration (WPA) to create employment for artists during the depression of the 1930s. Murals were a significant segment of the program. Artists were restricted to images reflecting the local community's standards and generally focused on the idealization and dignity of work. The styles and abilities of the artists varied; financial relief was a significant issue reason for the government's support. Most communities established a committee to select sketches from the submissions by anonymous artists. The methods the Mexican artists used to create frescoes were followed by many muralists in the United States. Most of the murals were commissioned for public or government buildings. Diego Rivera obtained private commissions, and David Siqueiros taught classes in America, both of them influencing the WPA artists. Since the Americans were not free to choose their subject matter, most WPA art was not based on the concepts seen in Mexico of social unrest. The Mexican muralists, who usually supported Communist ideals, influenced the themes of many WPA projects, bringing some congressional members to question the projects and reduce funding. As World War II started, the economy increased, and WPA projects were suspended.

Washington D. C.

The old Ariel Rios Federal Building (now the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building) in Washington D. C. was originally a post office constructed in 1934. In the buildings, twenty-five murals were selected, and some were controversial at the time because of nudity or revolutionary concepts. Others became controversial today based on stereotypical portrayals of different groups of people, an example of how values change over time.

Reginald Marsh

On one floor, the murals by Reginald Marsh (1898-1954) depict different aspects of the mail system. He studied the entire process, interviewed workers, and made sketches as he traveled around the system. Sorting the Mail (5.9.19) brings alive the energy and rhythm workers performed to move the mail through the sorting machines and into the bags for transportation. The New York Times paper called it a "brilliant orchestration of labyrinthine structural rhythms."[6] The upper section of the mural is painted in green, black, and white, depicting the machines moving the mail as the men with muscular physiques demonstrate strength. The mural displays the importance of technology and mechanization as well as the workers.

Alfredo Crimi

By the 1930s, the people who lived in cities, the country, and the newly emerging suburbs, spread across the United States. Mail was the primary method of communication, and Transportation of the Mail (5.9.20), by Alfredo Crimi (1900-1994), portrayed the multiple methods the system used to move mail and goods across the street or the state. In the foreground, the image of the young girl handing a letter to the mail carrier is the most basic form of mail. The rest of the mural depicts the different types of transportation. Whether a bicycle or a train, the mail moved from the city to the country.

Doris Lee

Delivery of mail to rural areas did not start until 1896. Over sixty percent of the people lived in rural areas; their mail was only delivered to a post office in the nearest town. The postal department experimented with delivery to individual farms, and in 1902, rural free delivery became permanent. By the 1930s, everyone who lived in rural areas had the same mail rights as those in the city. During this period, life in the country was idealized in paintings and writings. Doris Lee (1905-1983) created the mural Country Post (5.9.21), portraying the romanticized life in the country and the pleasure of receiving mail. The farmer and his son received tools in the mail as the woman opened her letter. Mail was delivered by whatever mechanism the carrier owned, generally by horse and wagon unless the lucky carrier owned a car.

Post Office Buildings

Post office buildings throughout the country were familiar places for the murals to be created.

Julius Woeltz

The Bauxite Mines (5.9.22) by Julius Woeltz (1911-1956) was initially installed in the post office in Benton, Arkansas. The mural was painted shortly before the Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbor when the bauxite mine was producing aluminum for weapons and planes. The mural demonstrates the open-pit mine techniques, the layers of bauxite strata visible as the men work, some of the miners drilling holes for the explosives while others load ore into the cars.

Marvin Beerbohm

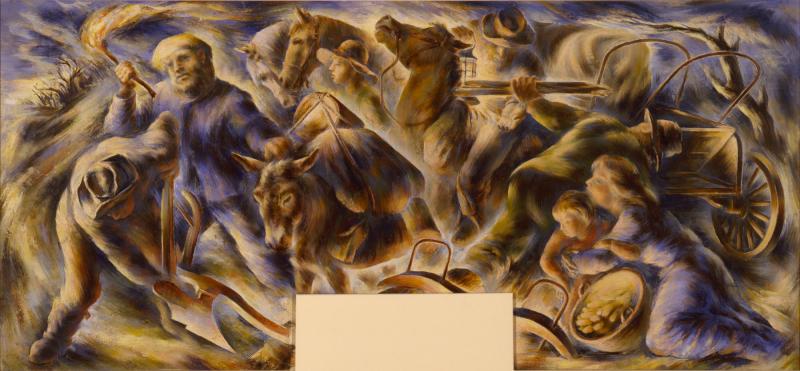

Pioneer Group at the Red Rock Line-1845 (5.9.23) by Marvin Beerbohm (1908-1981) was installed in the Knoxville, Iowa post office. When Beerbohm was meeting with the commission in the town to discuss the subject matter, he wanted to focus on local history. They chose a scene of the government forcing the Sac and Fox Indians from their land at Red Rock Line. The image shows the white settlers waiting on the outskirts to rush in and claim part of the land. Beerbohm knew there was a door in the middle of the mural, and he had to position the figures above the door in a semicircle. The scene of settlers is intense as they wait with lanterns and torches in the night sky. A local paper praising the artist wrote, "Shouts of excited drivers mingled with the yells of men on horseback carrying torches, flaring in the wind and small children, clinging to their mothers…in terror."[7] Of course, the mural did not portray what happened to the native people who were forced to move.

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\): Pioneer Group at the Red Rock Line-1845 (1940, oil on fiberboard, 43.2 x 82.5 cm, by Marvin Beerbohm, Knoxville Post Office, Iowa) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\): Pioneer Group at the Red Rock Line-1845 (1940, oil on fiberboard, 43.2 x 82.5 cm, by Marvin Beerbohm, Knoxville Post Office, Iowa) Public DomainMargaret Martin

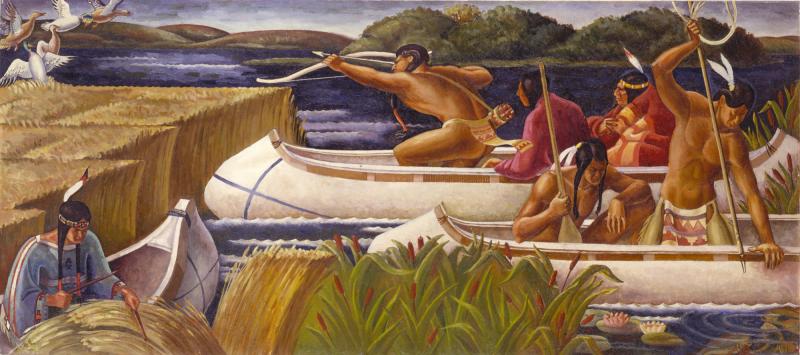

Indian Hunters and Rice Gatherers (5.9.24) by Margaret Martin (unknown) was prepared for the post office in St. James, Minnesota. The mural depicts an idealized version of native people hunting, fishing, and gathering wild rice, a testimony to the abundance of the region's natural resources. Many of the muralists want to include images of Native American life in some of the murals and their harmony with nature. The composite scene was unrealistic and did not reflect the images of the Native Americans who resided in the area.

Coit Tower

Lillie Hitchcock Coit was a philanthropist and eccentric figure in San Francisco who bequeathed part of her estate to the city with the direction to spend the money on a project to add beauty to the town. A tower was designed to sit on top of Telegraph Hill, visible from most of the city. The tower is 670.56 meters tall, made from concrete in a fluted design to avoid appearing top-heavy. In 1934, frescoes painted on the wet plaster surface over six months were part of the first floor. Over twenty-five, artists and assistants collaborated on the murals, the theme, "Aspects of Life in California." The murals were controversial at the time, many of the concepts too liberal or politically charged, including crime scenes, communist symbols, or banned books.

Maxine Albro

One of California's women artists, Maxine Albro (1893-1966), was an early muralist and was selected for the Coit Tower mural project, even at her young age. Part of the WPA Art Project was to help employ artists, including the requirement to hire female artists, a rare direction at the time. Previously, she made many trips to Mexico, studying the techniques of the Mexican muralists, and incorporating Mexican themes into her work. She was considered one of the pioneers in experimenting with new fresco techniques. Agricultural products were a significant export of California and her major theme. Although the murals California (5.9.25) portray the workers in the field picking and packaging the crops, the colorful scene masks the oppression of the workers during this period. After the murals were completed, the Literary Digest wrote about the different images in the tower. It stated, "Richest and most vivid is the wall painted by Maxine Albro, reflecting the sunny, abundant fields of California, and their prodigal flow of fruit and grain."[8]

Ralph Stackpole

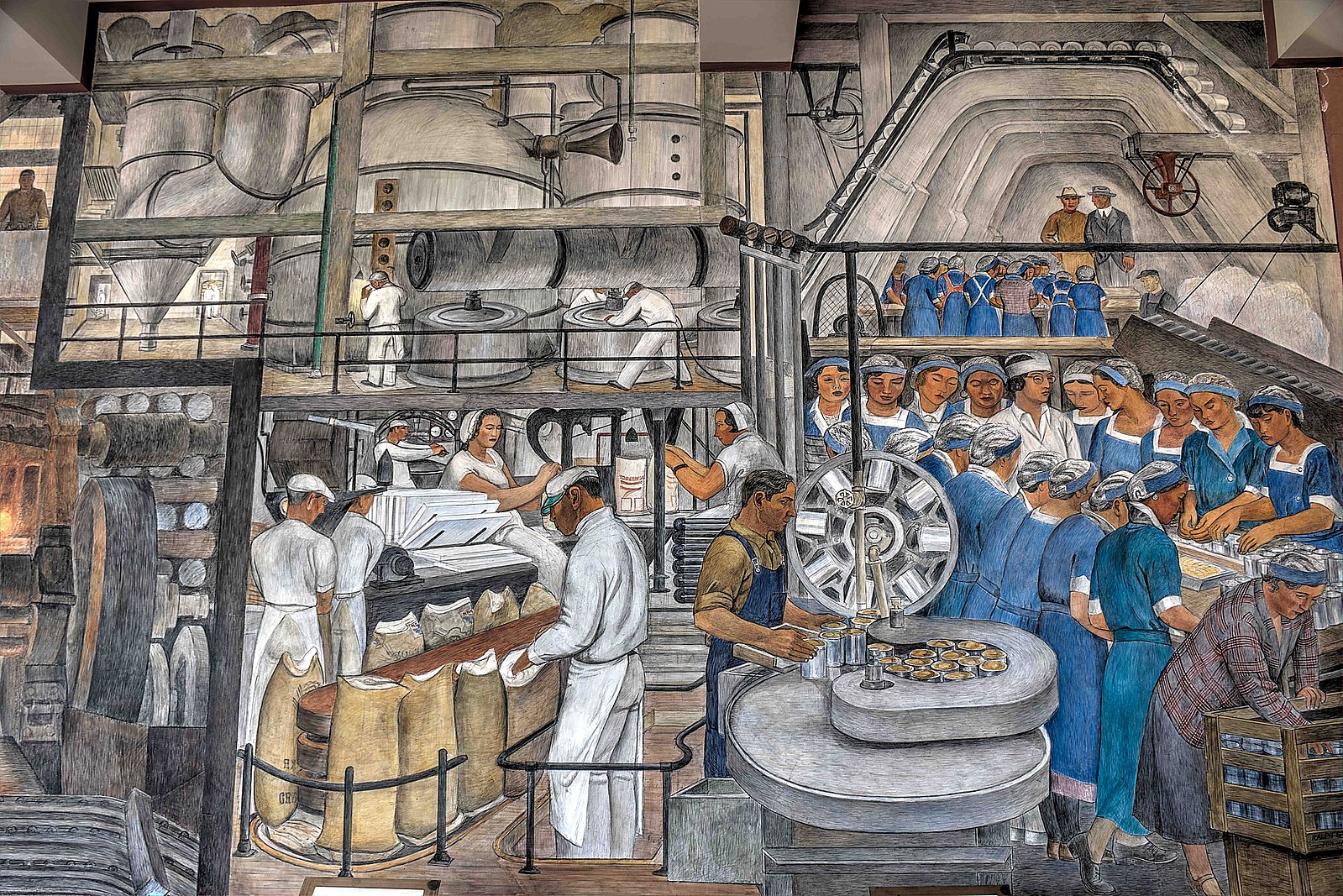

Ralph Stackpole (1885-1973) created a set of murals depicting some of the industries found throughout California, including chemical and steel mills. Industries of California (5.9.26) shows the people working in the cannery, agriculture, and the processing of agricultural products, a primary industry at the time in California. The people worked long hours on the production line, a combination of the focus on mechanization of the lines and the necessary integration of people.

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\): Industries of California (1934, 3.04 x 10.97 meters total set, by Ralph Stackpole) CC0 1.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\): Industries of California (1934, 3.04 x 10.97 meters total set, by Ralph Stackpole) CC0 1.0

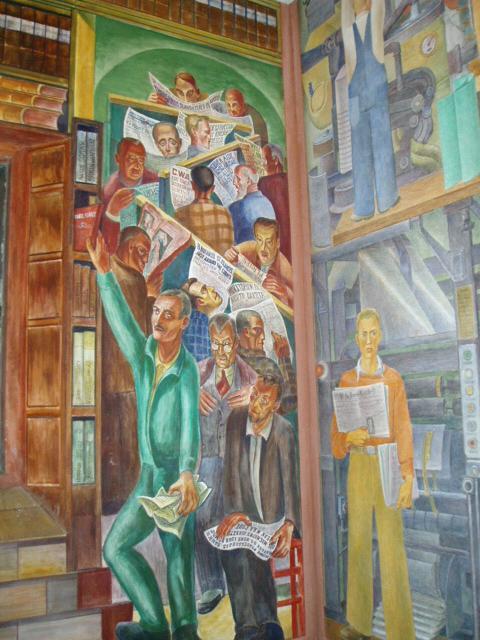

Bernard Zakeim

The Library (5.9.27) was created by Bernard Zakeim (1898-1985) and other assistants, becoming one of the most identifiable murals. The mural displays people surrounding columns of books and newspapers, some of the people reading, others looking at titles. The mural was controversial because the titles of some of the books were banned, censored, or otherwise restricted books.

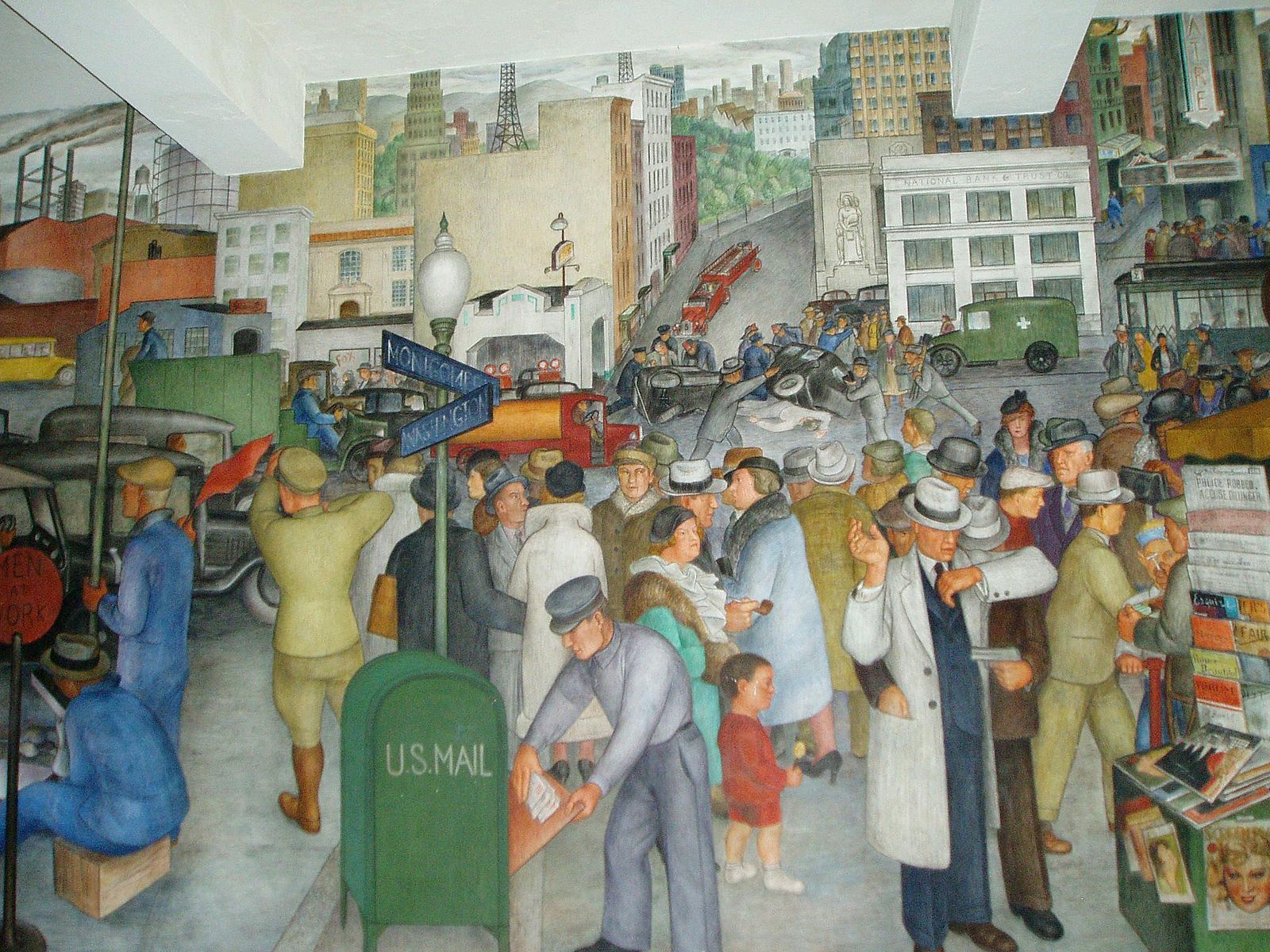

Victor Arnautoff

City Life (5.9.29) by Victor Arnautoff (1896-1979) is located near the library, a panoramic scene of city dwellers. Each person is busy pursuing their schedules, oblivious to surrounding activities. No one notices the car accident located in the center of the mural or the robbery occurring on the bottom right. San Francisco's major buildings were included in the mural; city hall, the library, and the Legion of Honor. Arnautoff, who oversaw the complete project, had studied with Diego Rivera and incorporated the newer Mexican mural techniques into the Coit Tower murals.

The depth of influence the Mexican muralists exerted on the WPA artists is unknown, although their style and techniques are visible in the American murals. David Siqueiros held multiple workshops for artists in America, Diego Rivera painted numerous commissions, and other artists studied his work. The Mexican muralists were able to incorporate political images and beliefs into their murals as the WPA controlled the themes and images in their murals. However, even though the WPA had close regulations, some artists were accused of being communists in the 1940s. The Mexican murals and the WPA murals were the precursors of today's modern murals. Graffiti artists started in the 1960s, using the new types of paint artists like Siqueiros pioneered, graffiti covering walls with political images and statements, graffiti emerging as a common form of contemporary art.

[1] Retrieved from https://teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_05.02.09_u

[2] Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/1934-the-art-of-the-new-deal-132242698/

[3] Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/diego-rivera-about-the-artist/64/

[4] Retrieved from https://www.nga.gov/education/teachers/lessons-activities/self-portraits/siqueiros.html

[5] Retrieved from https://www.theattic.space/home-page-blogs/2018/10/25/the-yankee-and-the-communist

[6] Retrieved from https://www.gsa.gov/real-estate/gsa-properties/visiting-public-buildings/william-jefferson-clinton-federal-building/whats-inside/wheres-the-art/reginald-marsh

[7] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/pioneer-group-red-rock-line-1845-mural-study-knoxville-iowa-post-office-1732

[8] Hailey, Gene (1936). California Art Research: Maxine Albro, Chin Chee, Bernard Zakheim, Andree Rexroth, Chiura Obata. San Francisco: California Art Research Project. pp. 1–15.