3.11: Modernism in Latin America (Late 1800s-mid 1900s)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174421

Introduction

The European academies played a significant role in shaping the style of artists in Latin America from the early 1800s to the mid-1900s. Many artists attended and received their formal education from academies in Paris, Madrid, and London. Modernismo, the Hispanic name for Modernism, was originally a term used to refer to literary works. At the turn of the twentieth century, the term also became synonymous with the art of this period. The art of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw close connections associated with modernist styles and tendencies in Europe. However, when the Latin American artists studied abroad and returned to Latin America, they shaped and contributed to an art conveying a Latin American identity.

Art can be a motivator of social change, and it became a goal of artists in modern Latin America. The early twentieth century was a period of political and social turmoil throughout Latin America. The Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, overthrew the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. After ten years of fighting the Mexican Revolution, some artists believed the Revolution did not accomplish enough or solve the problems of poor Indigenous populations. Additionally, the region's artists started concentrating on the effect of social changes impacted by political ideologies such as Marxism, Socialism, and Communism.

In Mexico, the art academy, and its conservative nature, became the subject of criticism amid a growing tide of pessimism and resentment. As a result of political and artistic changes, Mexican artists began to assert populist imagery and content by drawing inspiration from the satirical illustrations of José Guadalupe Posada. In 1921, Alvaro Obregon became President of Mexico and directed his minister of education, Jose Vasconcelos, to develop a Mexican mural program to capture a national consciousness. The murals, painted most often on public buildings, were art for the people. Posada addressed contemporary social issues in his work, and these issues became the primary subject matter of the Mexican muralists.

Printmaking

Graphic arts became an important medium of expression among illustrators and lithographers in both Europe and Latin America. The Latin American graphic arts served as satirical observations of daily life, with illustrations addressing social and political issues. The Latin American graphic arts were most utilized and effective in regions that experienced the most pain because of the continued democratic reforms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

José Guadalupe Posada

Considered the father of the graphic arts movement in Mexico, José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) was one of Mexico's most famed print artists. During this tumultuous era, Posada was influenced by the social injustices in Mexico from the dictator Porfirio Diaz and the initial years of the Mexican Revolution. Often, his graphic images criticized the inequality and social injustice during Porfirio's rule. Combining his Calavera prints with political messages, Posada conveyed that once we are dead, everybody is the same - just bones. Many of his visual social and political commentaries got him in trouble during his life, including fleeing printing shops and serving jail time. Posada is most well-known for working in Mexico City with Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, who owned a print shop. Arroyo's shop was located near the Art Academy of San Carlos, and artists like the great muralists José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera claimed they watched him work and were also influenced by Posada's goal of creating art for the people.

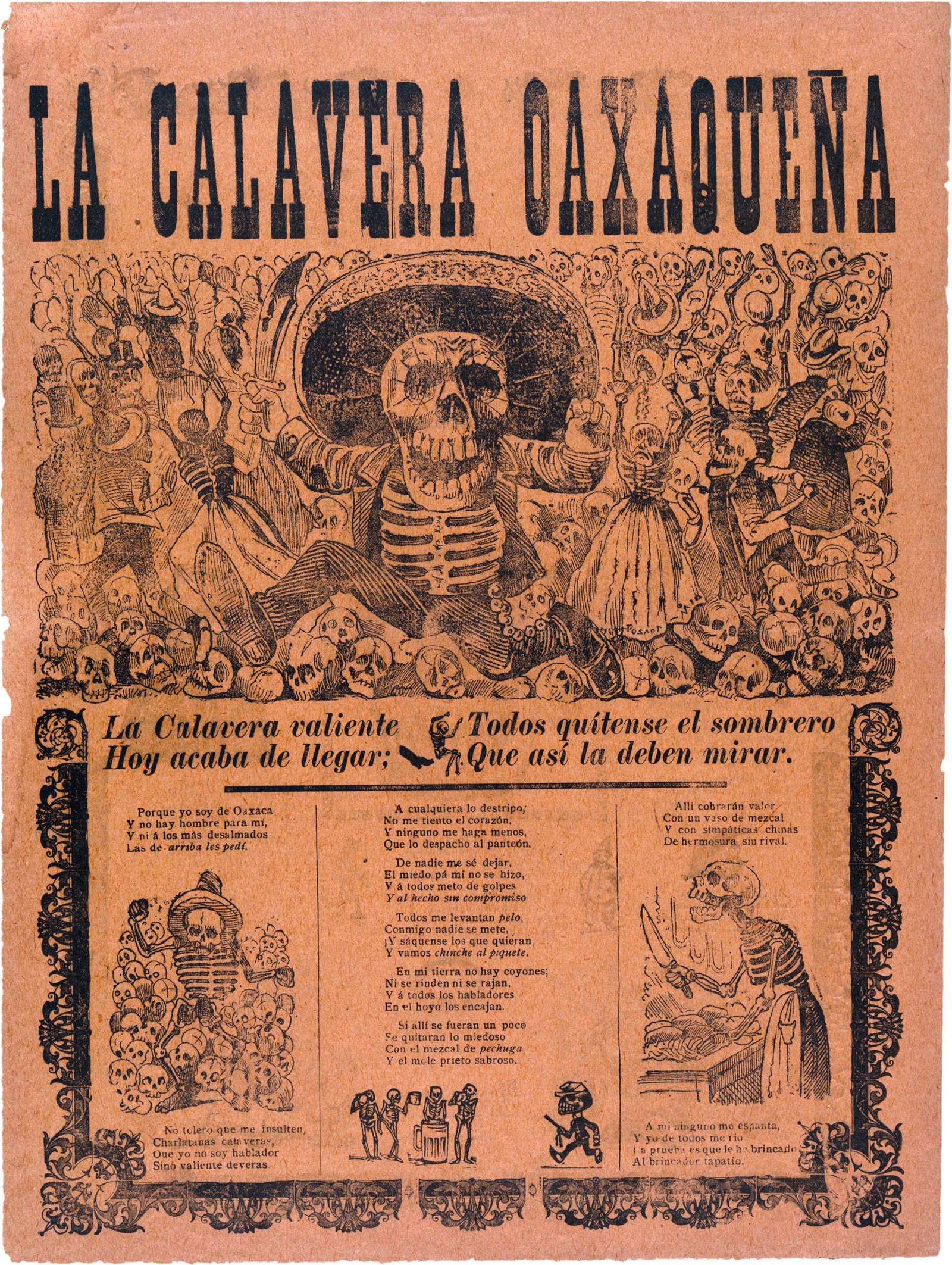

Posada used printmaking to ridicule the privileged and wealthy. As seen in La Calavera Oaxaqueña (5.11.1), his prints were used as a social and politically sarcastic commentary on the political leaders who were indifferent to the Indigenous poor. He recognized the importance of art that would be available to the average or less fortunate population, so he created illustrations for the newspaper broadsides, like tabloids today. The prints were genuine "art for the people," as they would be made available to all.

Although Posada worked with many subjects, he is popularly known for his Calaveras (5.11.), or skeleton imagery. The image of the grand electric skeleton (5.11.2) was part of the newsprint. The large skeleton appears to be hypnotizing the group of skulls sitting on the ground as the skeletons in the electric streetcar appear to be watching. The newspaper article wrote about the transition from animal-powered streetcar to the new electrical, a technology to help propel the country into the 20th century.

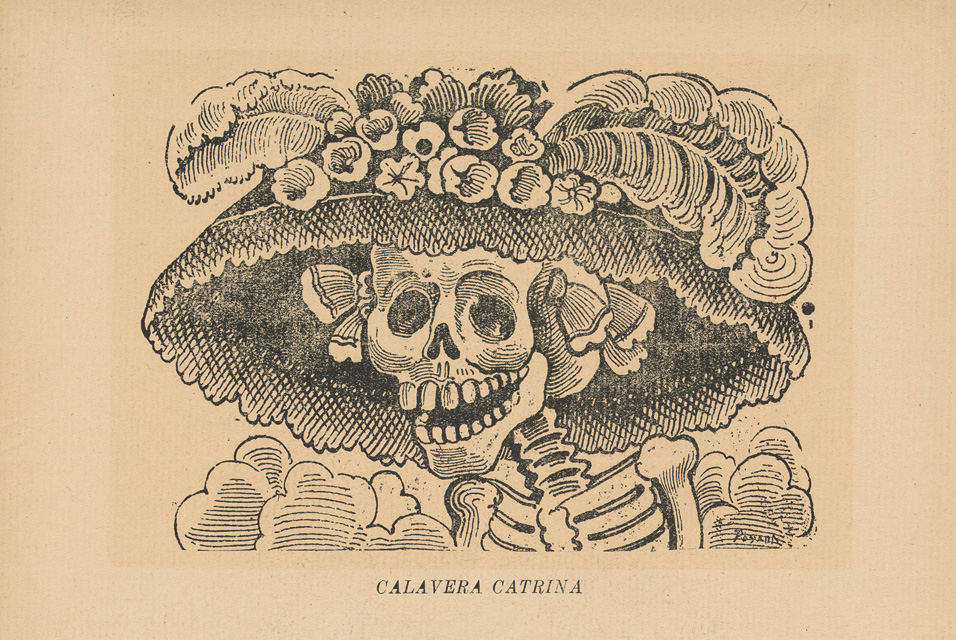

La Calavera Catrina (5.11.3) portrays a skeleton in an elegant hat. La Catrina has become the symbol for the Mexican Día de Muertos.

Diego Rivera paid homage to Posada by placing Posada's famous Catrina figure in the mural titled Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park (5.11.4), which he originally completed for the Coronado Hotel in Mexico City. The character La Catrina became popular through the image on Rivera's mural. Rivera used Posada's print image and gave Catrina a body and elegant clothing as she stood in the middle of his mural. Today, the traditional form of La Calavera Catrina is found in multiple types of artworks.

.jpg?revision=1)

Photography

Latin American Modern Photography

Manuel Álvarez Bravo

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (1902-2002) was the first significant photographer and leader in Latin American photography. Although he took classes at an art academy, Bravo taught himself photography. His work focused on ordinary images, rejecting the picturesque while defining Mexican heritage. Several unseen and unpublished photographs were found in Bravo's archives and assembled in a new show of 168 black and white images. Most of the photographs were printed in silver on gelatin, while some had to be digitally printed. Many of the people seen in the images are unidentified. The photograph of the young woman (5.11.5) reflects Bravo's interest in the peasant population and the roots of the local Mexican people. She sits with her eyes closed, a minute of quiet. Bravo did not pose people in the traditional formal style.

/Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Unknown, by Secretaría de Cultura CDMX CC BY 2.0

/Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Unknown, by Secretaría de Cultura CDMX CC BY 2.0Martin Chambi

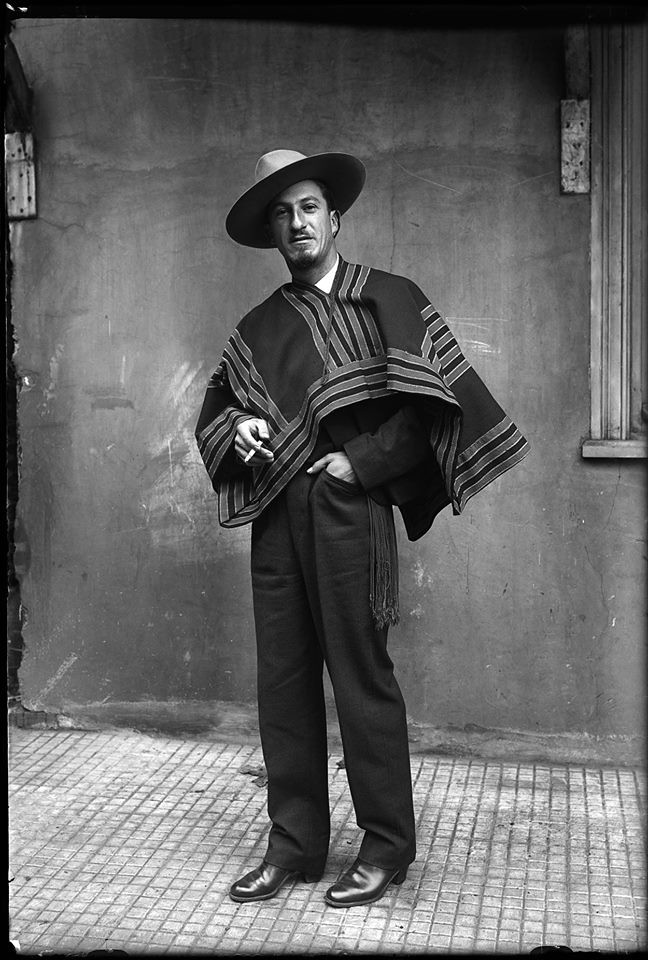

Martin Chambi (1891-1973) was born in an Andean village in Peru. His education was limited as he worked in the mines at an early age. Chambi first saw a real photo when a photographer from England came to take photographs at the mine. Only a teenager, he saved his money to travel to the city and learn photography. Chambi was successful and became part of the Peruvian artistic community. However, he continued to focus on the Indigenous culture and Peru's identity. In 1936, Chambi went to Chile and photographed people throughout the region. It is unknown why he wanted to make the trip; however, he left a legacy of his journey and a set of photographs stored until recently. The huaso (cowboy) (5.11.6) is standing outside, dressed in typical clothing. The huaso was considered an excellent horseman who lived on a hacienda or large estate. The man is wearing a chamanto (reversible poncho) made of wool and sometimes silk accents with a chupalla (flat-top straw hat) on his head.

Impressionism

Impressionism significantly changed the process of painting, influencing artists around the world. The main passion the Impressionistic artists all shared was light and color, how the light made colors intense or changed the hue.

Joaquín Clausell

Impressionism, a French artistic movement, investigated how light and color affected the reality of the observer. Impressionists accomplished this through multiple methods and techniques, including thick impastos and heavy brushstrokes, to successfully interpret the world they observed around them. Impressionist artists in Latin America included Mexico's Joaquín Clausell (1866-1935) and Venezuela's Emilio Boggio (1857-1929). Their heavy and loose brushwork typified the nature of the visual sensations of light. They displayed vibrant colors to portray their subject matter – like how the Impressionists of Paris were working. The themes explored by Latin American artists coincide with their French counterparts, and they worked in plein aire. Painting outdoors was a break from academic traditions. These influences of outdoor painting in Plein aire, loose brushwork, and vibrant colors are visible in Clausell's Landscape with Forest and River (5.11.7). He painted the image after visiting Claude Monet's studio, influencing his use of blue and green as the light shines on the river.

Emilio Boggio

The works of Venezuelan artist Emilio Boggio have similar stylistic qualities as Clausell. Influenced by his time in Paris in the 1860s, he chose subject matter reflecting the working conditions of the early twentieth century. As seen in Boggio's painting titled End of the Day (5.11.8), he painted a scene reflecting the title of the painting, suggesting the potential of the evening's leisure activities. Leisure activities were common subjects in Paris during the height of the Impressionist movement. Boggio's loose brushstrokes and use of paint also reflected the methods employed by the European Impressionists.

Pedro Figari

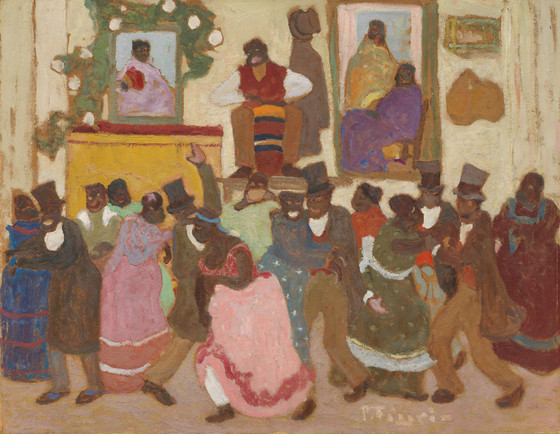

The Uruguayan artist, Pedro Figari (1861-1938), worked early in his life as a lawyer and, at the age of 60, turned his attention to painting and subsequently moved to Europe. His modernist approach was unusual. Stylistically, Figari's work intersected Impressionism and Post-Impressionism; however, he didn't include modern scenes of life, trains, locomotives, or café scenes, which European artists often painted. Instead, Figari painted scenes of his childhood in Montevideo, Uruguay. His personal experience of local customs, especially the African drum-based dance Candombe, performed in Uruguay, is displayed regularly in his paintings. The liveliness and enjoyment of the dance are visible in his painting, Dancing People: Candomb (5.11.9).

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Dancing People: Candombe (1920, oil on board, 74.9 x 90.1 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Dancing People: Candombe (1920, oil on board, 74.9 x 90.1 cm) Public DomainSurrealism and Constructive Universalism

Surrealist work was tense and sexual based on hidden psychological forces in the subconscious. The rational mind was suppressed, and imagination locked in by societal controls. They didn't look for art in real everyday life; instead, they used the impulses of the primitive unconscious mind.

Rufino Tamayo

Maria Izquierdo, and Izquierdo’s one-time lover, Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991) created art like their Surrealist European contemporaries. Surrealism, a European art movement that began in the 1920s, believed in the irrational, the emotional, the personal, and the subconscious. Hombre con un Gran Sombrero (5.11.10) is an example of Tamayo’s bold, blocky image. The almost disassembled man is lying on the bench, his red hat perched sideways. Looking closely, the viewer can also find other objects in the painting.

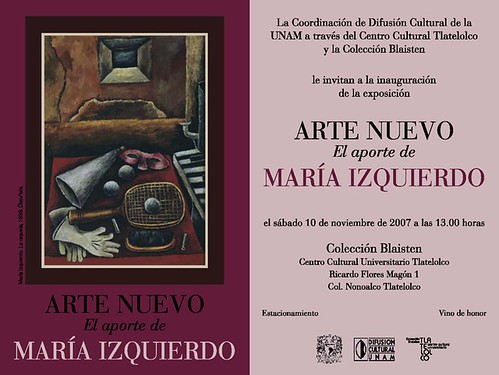

Maria Izquierdo

Maria Izquierdo (1902-1955), an artist who created esoteric paintings, often focusing on women and their concerns, was enrolled at the art school where Diego Rivera worked. She had a relationship with Rivera, which got her kicked out of school and later forced him to resign. Her work often incorporated themes of loss, consequences, traditional Mexican values, and feminism – although she also rejected being called a feminist. The esoteric quality of her work placed her in the Surrealist category, though she also rejected that identification. The cover of an art book portrays her image, The Racket (5.11.11). Various objects are placed in distinctive ways and viewable from different levels resembling Surrealism. The darkness out the open window and past the tunnel brings the quality of a hallway. As seen in her other works, she brings the feeling of the experience found a long journey to freedom; in the open air, out the window.

The high point of her life was when her dream of painting a government-sponsored public mural in Mexico was realized, only to be canceled. Izquierdo was rejected because her mentor, Diego Rivera, interfered. Along with David Alfaro Siqueiros, Rivera claimed she was not experienced enough to complete the project. Undoubtedly, her focus on the concerns of the female also played a part. The project was canceled, leading to a period of suffering for the artist. Izquierdo was a professional artist recognized internationally and was the first female Mexican artist to exhibit her work in the United States. Today she is often overlooked and overshadowed by her contemporary, Frida Kahlo.

Anita Malfatti

Anita Malfatti (1889–1964), a South American Brazilian female artist, painted in many European abstract modern art movements popular in the early 20th century while studying in Europe. Sometimes she was inspired by Cubism's flattened and twisted effects, and other times incorporated strong, vibrant, and non-naturalistic use of a color like the Fauves. In The Fool (5.11.12), Malfatti created imagery generally upsetting the conservative Brazilian public. Although she earned a one-person exhibition in Sao Paulo, an important event for a woman to have her show, she was rejected by academic art. A lack of a clear Brazilian identity in her works made her exhibition all that more controversial.

In Tropical (5.11.13), Malfatti painted a classic Brazilian theme like the Post-Impressionists. The young woman appears mixed race with dark eyes and hair, holding Brazilian fruit in her basket. If Anita Malfatti is considered the instigator of modernism in Brazil, then Tarsila do Amaral as the propellent!

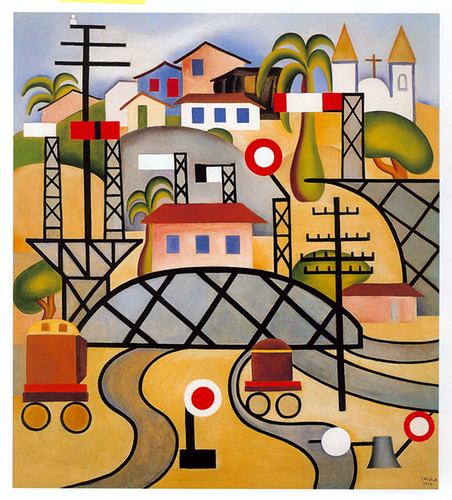

Tarsila do Amaral

Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) also studied different movements in Europe. However, she was not as direct in her interpretation of Cubism. Amaral chose abstracted tropical landscapes and portraiture upon her return to Brazil in 1924 after studying in Paris. She blended the techniques of modern European masters, highly abstracted yet very personal representation of the people and land of her native country. In her work, Central Railroad of Brazil (5.11.14), Amaral used the Cubist forms to document the modern progress of Brazil along with the bright colors other modernists used.

In the image, Postcard (5.11.15), Amaral displayed her desire to return to working with the bright colors of crayons to depict the city of her homeland. She remembered using crayons as a child and was asked to reject them in art school; however, the vivid colors influenced her oil paint colors.

Amaral's painting Abaporu (5.11.16) was one of her new styles to transform European methods into distinctly Brazilian. The background is simple in its form, a small ground hill for the earth, a few green cacti, and the pale blue sky lit by the yellow sun. The figure, however, is very distorted. The person is nude, ageless, and sexless. The immense foot and hand anchor the bottom of the painting as the figure grows smaller when moving upward. A small arm supports the head, the face contemplative, sad, bored, or however a viewer wants to define the emotion.

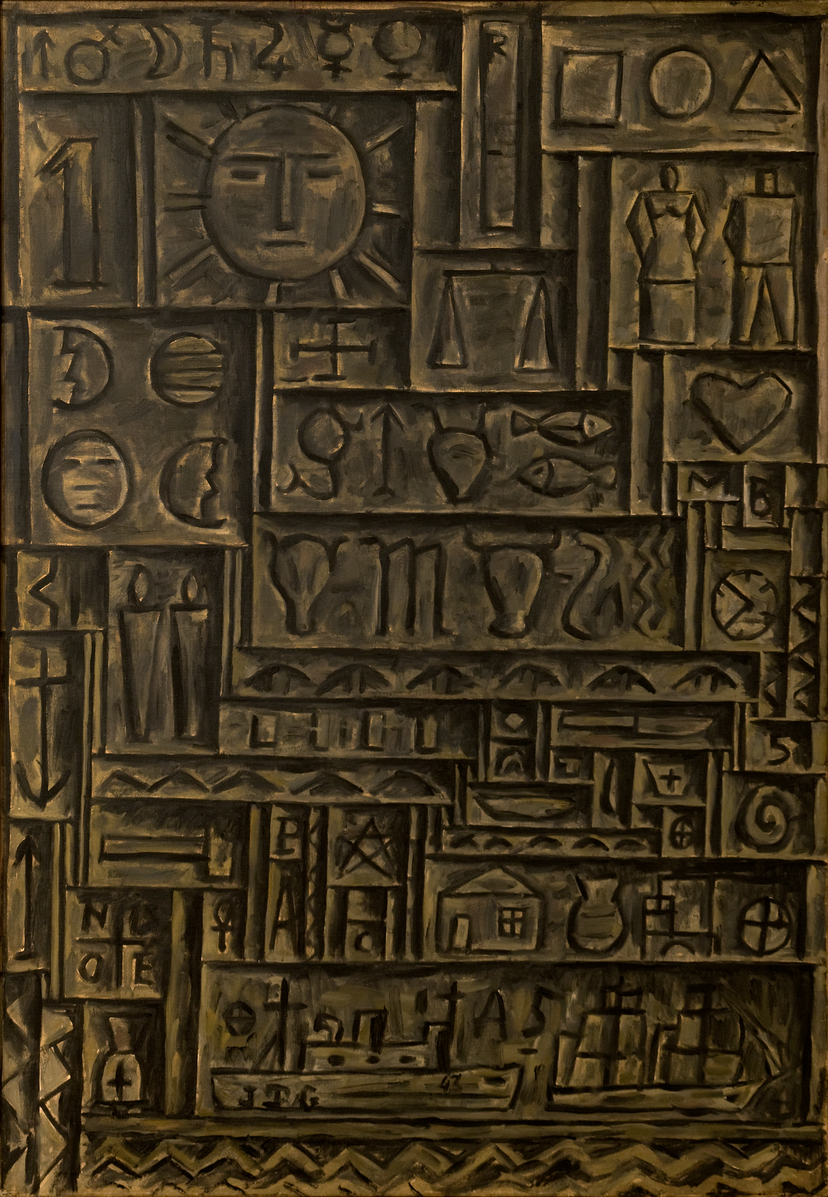

Joaquin Torres-Garcia

Another important South American modern artist during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was the Uruguayan painter-sculptor Joaquin Torres-Garcia (1874-1949). After studying and earning a name in Europe during the 1920s, Torres-Garcia became artistically and historically the most prolific artist in the Latin American region during the early twentieth century and worked in numerous modern styles. His works in the Constructivist style included references to his life in South America. In the piece, Constructive Painting (5.11.17), he had symbols of the cross, the church, and the sun – all familiar symbols in Latin America. In 1942, he eventually developed his style named Constructive Universalism. The style was based heavily on cultural identity with abstract symbols and forms chosen from pre-Colombian cultures.

Cândido Portinari

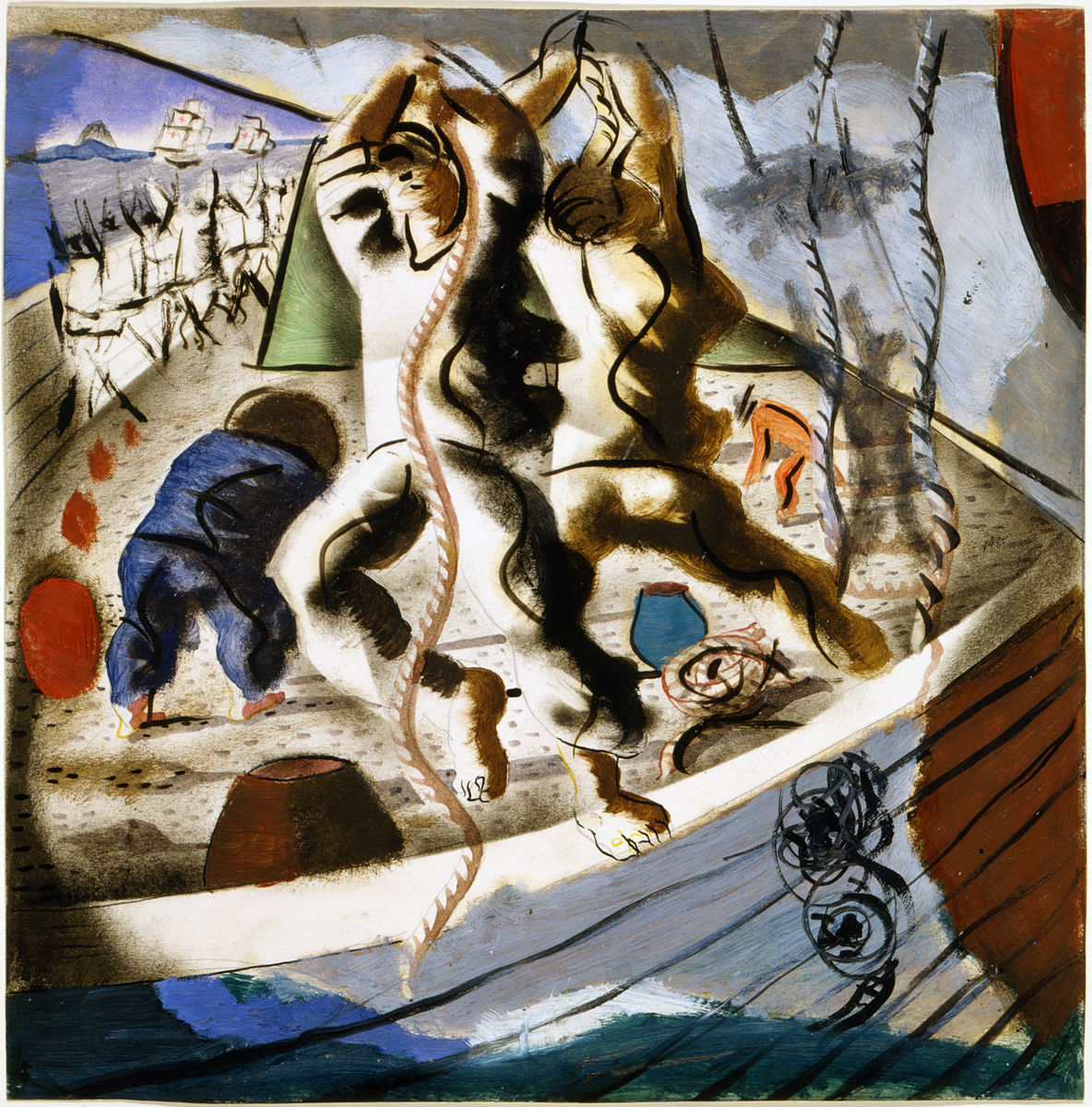

Cândido Portinari (1903-1962) is one of Brazil's most influential painters who painted thousands of images, from small sketches to murals. Portinari grew up on a coffee plantation and understood the depth and colors of the blue sky or the dark earth. Part of his artistic training was in Europe, and he returned to Brazil determined to illustrate authentic Brazilian culture. He painted rural and poor, immigration and refugees, labor and wealth, documenting Brazilian history using different modernist methods. Portinari created a preparatory drawing for the Discovery of the Land (5.11.18) he would paint as a mural in the Library of Congress. Portinari depicted the first time a European found land across the ocean. However, the image represented no one specific person, and it might be Cabral who was Portuguese and landed in Brazil or Columbus, who landed in the islands.

The government of Brazil donated two murals to the United Nations and were installed in their headquarters. Portinari was selected as the artist and painted War depicting human suffering and the madness of war. In the mural, Peace (5.11.19) used simple forms, the mural bathed in light to demonstrate understanding and brotherhood.

José Sabogal

José Sabogal (1888-1956) was from Peru and became a leader in multiple methods and movements of Peruvian art. He traveled extensively in Europe and attended the School of Fine Art in Buenos Aires. Although he was a Spanish descendant, he encouraged pre-Columbian cultures and indigenism. In 1922, he went to Mexico to meet the muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros and promote Peruvian art. His success in Mexico inspired him and the growth of artists in Peru. The focus was on indigenism, bringing forward the legitimacy of Indigenous cultures and rejecting dominant society's unnatural controls. El Recluta (5.11.20) is an example by Sabogal to focus on the local culture. The man in the painting looks confident, and aware of his position. His robust features are accented and defined as Peruvian.

Oswaldo Guayasamin

The works of Oswaldo Guayasamin (1919-1999) are very distinctive, almost like caricatures. His figures had extended features, deep shadows, odd lines on the skin, and usually with powerful emotions. His work was based on the Indigenous people in South America and the struggles of the regions. As a native of Ecuador, he was quite aware of the suffering of people in the region. Senora de Cos (5.11.21) demonstrates Guayasamin as an Ecuadorian Expressionist. Her eyes are oversized, and her neck elongated, the neck tendons overly visible.

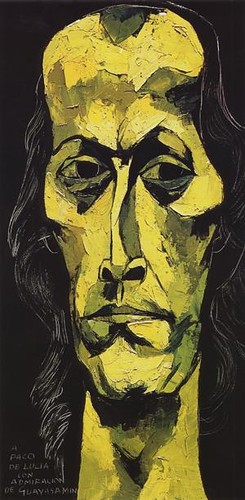

Guayasamin and Paco de Lucia (5.11.22) were friends, de Lucia a well-known guitar player. When Guayasamin started the painting, he used broad black strokes to outline his characteristic exaggerated form. The portrait's dark eyes seem to be looking at the artist, his brows together as though observing the painter.

Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\): Paco de Lucia (1994, oil on canvas) by KUUNSTKUULTUR CC PDM 1.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\): Paco de Lucia (1994, oil on canvas) by KUUNSTKUULTUR CC PDM 1.0Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (1886-1957) is generally known today as the great Mexican Muralist of the 20th century. He received great acclaim as a great artist at the Academy of San Carlos in his early years, earning a scholarship to travel in Europe. He spent more than a decade traveling around Europe, living in Spain, France, and Italy. Rivera's time in Paris brought him in contact with modern European artists, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. In Italy, he studied the Proto-Renaissance artist Giotto.

Although not explicitly considered or classified as a Cubist, Rivera became a member of the Cubist circle in Paris. One of the great cubist paintings he completed while abroad in Europe is Zapatista Landscape (5.11.23). Zapatista refers to Emiliano Zapata, the celebrated leader of peasant guerilla forces and the Mexican revolution. In the painting, Zapata has a sombrero, gun, and serape in front of the mountains around the Valley of Mexico. This painting demonstrated Rivera's deep connection to his home country when he was living in Europe. Although the Mexican Revolution influenced his later mural work, Rivera was in Europe during the ten years of fighting in Mexico. Zapatista Landscape is one example of many, where Rivera incorporated Mexican symbols.

Rivera explored other popular modern European art movements while encompassing symbols of Mexico. Stylistically, The Café Terrace (5.11.24) displays the influence of Pointillism with the large dots of color and objects on a Parisian café table. The cigar box in the upper right-hand corner references Mexico. The partial letters spell "BENITO JUA," referring to Benito Juarez, the first Mexican president of Indigenous origin. Rivera's Mexico birthplace substantially impacted him and certainly influenced his future political and revolutionary fervor even at this early date.

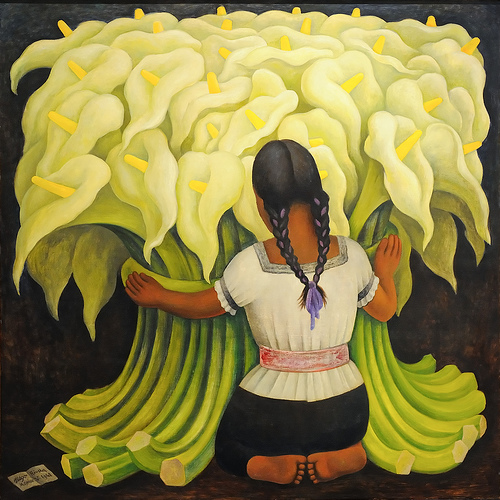

Although Rivera is well known for his murals, he continued painting on small canvases. His concern for the Mexican worker is seen in his many paintings glorifying lily flower sellers. The painting The Flower Vendor (Girl with Lilies) (5.11.25) is a mix of Cubist volumes, abstract shapes, and flattened forms, all influenced by European stylistics. Additionally, simplification can be seen in the generalized faces or hairstyles of the women. Thematically, he celebrated everyday Mexican people and culture, a repetitive theme.