3.9: Bauhaus (1919-1931)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174419

Introduction

The Bauhaus opened its doors in 1919 and was considered a radical new design school located in Weimar, Germany. Founded by Walter Gropius, he developed the school's manifesto: The school would be open to "any person of good repute, regardless of age or sex, and even went on to clarify that there were to be 'no differences between the fairer sex and the stronger sex,' in a time when women could not attend college."[1]

After World War I, Germany became a land of the old bourgeois of industrial and militarism caught between Russian Communism and Nazi racism. The old was out, and the creation of new appeared conceivable, allowing modern art and ushered the creation and spreading of idealistic perceptions of art and design foundations. The opening of the art school after World War I was simply known as the Bauhaus (5.9.1)

The Bauhaus philosophy revolved around an art utopia, an entirely new concept in the art world. The world was in crisis, and Gropius "established a romantic new beginning which aimed to create a new environment and release creative spontaneity in everybody."[2] The school had a prominent pedagogy with the aim of educating the senses. However, the school still adjusted to the outside pressures of the social and political changes in Europe. The main principles of the Bauhaus were:

- No border between artist and craftsman

- The artist is an exalted craftsman

- Form follows function

- Complete work of art

- True Materials

- Minimalism

- Emphasizes on technology

- Smart use of resources

- Simplicity and effectiveness

- Constant development

Men of the Bauhaus

Although the Bauhaus was only open for fourteen years, the ideas perpetuated beyond Germany and influenced many artists and companies.[3] The core principles were a profound conception—reimagining the material world to imitate and create beautiful objects—perhaps an idealistic craft guild.

Walter Gropius

Walter Gropius (1883-1969) was a German architect and founder of the Bauhaus, drafted during World War I and awarded the Iron Cross twice. Gropius was responsible for training many great artists such as Paul Klee, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Wassily Kandinsky. The Bauhaus was an instant success and a sought-after school by artists. Gropius designed the Bauhaus school's buildings, advancing the art of modern architecture. An essential aspect of the training was the stage workshops which sought to bring together performing arts and the visual arts, creating an interdisciplinary methodology. The idea to bring mass consumption of art products to the world endures today. The Bauhaus trained their artists in the simplistic movement where less is more.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) was a German architect and one of the pioneering leaders of modern architecture and director of the Bauhaus from 1930-1933. Von der Rohe was the designer of the famous Barcelona chair from 1929 (5.9.2) with material resembling blue jeans. The most recognizable chair in the world is a tribute to the Bauhaus movement based upon the marriage of design and craftsmanship.

After the Nazis closed the Bauhaus, most artists fled the country, and Van der Rohe settled in Chicago. He designed the IBM Plaza (5.9.3) in Chicago and the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library (5.9.4) in Washington, D.C. The library is 37,000 square meters of steel, brick, and glass, representing one of Washington's few modern architectural buildings.

He also designed the Seagram Building (5.9.5) in New York and redefined the concepts for modern skyscrapers with the structure set back from the street on an open plaza. The supporting configuration of the building was covered with a facing of bronze combined with dark glass.

.jpg?revision=1)

Peter Behrens

Another influential Bauhaus architect was Peter Behrens (1868-1940) from Germany. Behrens was a designer influenced by industrial classicism. His building, the AEG Turbine Factory (5.9.6) built in 1909, was revolutionary in its design features, with windows 100 meters long and 15 meters high on both sides of the electrical company building.

Behrens also designed everyday goods like Clocks (5.9.7), the form of an industrial clock that was intended for the AEG factory.

The Tea Kettles (5.9.8) are similar in three sizes with an electrical cord that could be unplugged for washing. When the Bauhaus finally closed in 1933, many of the students carried on the tradition of modern design. Everyday items were seen as art pieces yet functional.

Women of the Bauhaus

The men of the Bauhaus were all well-known icons of the early 20th-century art scene. The forgotten women of the Bauhaus worked beside the men making groundbreaking designs and were essentially left out of written history. Women (5.9.9) enrolled in the school and were encouraged to pursue weaving instead of the male-dominated painting, architecture, and carving. They thought women could only handle two-dimensional art. The women artists persevered and became architects, industrial and graphic designers, and photographers and laid the groundwork, advancing art and design legacy. They demonstrated grit and tenacity, paving the way for other women in the future. The past decade brought forward the women of the Bauhaus as a formative group of artists who were long forgotten with immeasurable lasting effects on art in the last 100 years.

Otti Berger

Otti Berger (1898-1944) was born in Zmajevac, Croatia, and enrolled in the Royal Academy of Arts and Crafts before continuing her studies at the Bauhaus in 1926. Heralded as one of the "most talented weavers," Berger started "experimenting with methodology and materials during the course of her studies at the Bauhaus to eventually include plastic textiles intended for mass production."[4] She continually developed an expressive approach to weaving, creating masterpieces, and pushing back on the idea it was women's work. Berger assumed the position as the head of the department in weaving after Stölzl abdicated the seat. The sample textile book (5.9.10) is a collection of Berger's best weaving from her time at the Bauhaus. She wove many different patterns using mercerized cotton and synthetic dyes, demonstrating the loom was not just a tool to produce a woven textile.

Her Book (5.9.11) is a weaving spectacular with a herringbone pattern in two different directions in three different colors. In 1932 Berger opened her textile factory in Berlin and worked until she was shut down by Nazi rule as she was Jewish. To escape the Nazi regime, she applied for a visa to relocate to Chicago and join the New Bauhaus School in Illinois. Her application stalled; she was arrested in Berlin and taken to Auschwitz, where she was killed in 1944. Berger's weavings live on in several collections around the world.

Anni Albers

Anni Albers (1899-1994) was a German artist who studied painting from an early age and entered the Bauhaus in 1922. Although interested in painting, she was required to take a weaving class and began experimenting with materials from other workshops—predominantly geometric design work. Becoming a quick master of the loom under Stölzl, Albers established an unusual graphic vocabulary of geometric designs consisting of cellophane, copper, and nylon, in addition to the usual weaving materials. Albers met her husband at the school, and when the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close in 1933, the Albers moved to North Carolina and taught at the Black Mountain College, of the many "new Bauhaus's" in the United States. By 1949, Albers was the first woman artist to have a solo weaving show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

While at the Bauhaus, Albers focused on experimental materials to use on the looms and discovered how sound was absorbed and the light was reflected on a cotton/cellophane curtain. In Design for a wall hanging (5.9.12), Albers created miniature gouache paintings drawing the design she would weave on the loom. The striking design is geometric and picturesque, using only a few colors with yellow dominating, the grey and green which are complementary colors.

%252C_Design_for_Wall_Hanging%252C_1925.jpg?revision=1)

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher (1899-1944) was a German designer studying at the Reimann School in Berlin and then the Bauhaus. She was one of the Bauhaus' few women to switch from the weaving workshop to the male-dominated wood-sculpture department. Accepted into the Wood Sculpture Workshop, she designed children's furniture and toys, becoming a household name, much to the chagrin of Walter Gropius. He believed women could not contemplate three dimensions.

She invented several successful toy and furniture designs there, including her "small ship-building game" (5.9.13), which remains in production today. The game manifested Bauhaus's central tenets: its 22 blocks, forged in primary colors, could be constructed into the shape of a boat but could also be rearranged to allow for creative experimentation. Play was encouraged at the Bauhaus in all classes, and Siedhoff-Buscher made toys that encouraged creative development in students in the local kindergarten schools. The toy could also be easily reproduced, bringing much-needed sales to the school. Siedhoff-Buscher also became known for the cut-out kits and coloring books she designed for publisher Verlag Otto Maier Ravensburg. But her most pioneering work proved to be the interior she designed for a children's room at "Haus am Horn," a home designed by Bauhaus members that exemplified the movement's aesthetic. Siedhoff-Buscher filled it with modular, washable white furniture. She created each piece to "grow" with the child: a puppet theater could be transformed into bookshelves, a changing table into a desk. After graduating from the Bauhaus, Siedhoff-Buscher had children and became a stay-at-home mother, abandoning her art. Siedhoff-Buscher left a legacy of influential designs after her life was tragically ended during a bombing raid in 1944 in Buchschlag.

Gunta Stölzl

Gunta Stölzl (1897-1983) was born in Munich, Bavaria, and is known as a textile artist and facilitated the development of the weaving workshops at the Bauhaus. In 1919 she worked to become the director of weaving at the school and mentored students in the shop during her tutelage. During Stölzl's first year, she began to refer to the weaving workshops as the "women's department" due to the gender roles within the school.[5] Immediately seen as a leader, she began to highlight artistic expression in weaving, developing new techniques and processes elevating the craft to fine art.

Stölzl even reopened the abandoned dye studios utilizing the many colors and synthetic materials available, creating stunning weavings. Implementing math and geometry classes into the program, students experimented with the fabric, color, light refraction, and sound absorption. Breuer designed the Marcel Breuer Chair (5.9.14), and Stölzl wove the backrest and seat cushion.

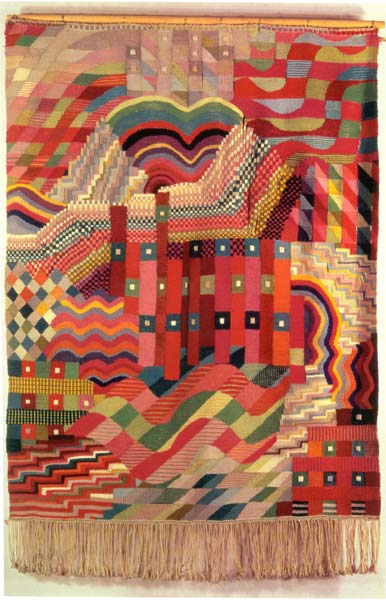

Using the traditional Bauhaus color scheme, she incorporated the fabric into the design giving it more significance than a conventional seat cover. Five years later—Tapestry was woven—showcasing her remarkable talent (5.9.15). The complex piece is expertly woven in multiple directions and colors, providing interest in all areas of the tapestry. The centerpiece is a linear alignment of similar hues of red with a complementary shade of green squares. The rolling "hills" anchor the centerpiece with similar colors. Stölzl wove for decades after the Bauhaus creating a fantastic body of textile art.

Margarete Heymann

Margarete Heymann (1899-1990) was a German ceramic artist and studied at the Bauhaus in her early life. She was guided toward the weaving workshop, refusing to follow her female peers, and moved into the ceramics workshop. Surviving a year in the all-male-dominated workshop, she left and started a ceramic workshop. Designing angular objects painted with colorful glazes, their company employed over 120 artists, and Heymann's ceramics were a quick hit selling in shops in Europe and the United States. Porcelain (5.9.16) is a beautiful example of a newly designed teapot in a vivid teal glaze. The unique circular teapot is a playful design that many people thought was a revolution in purpose.

Unfortunately, Heymann's husband and brother were killed in 1928, leaving her with young children and running a company. By 1931, sales began to drop off with the political atmosphere in Germany. She sold the company in 1934 and fled to England to escape Jewish persecution devoting the rest of her life to Greta Pottery, a new company. Refusing to live by the rules, she was a shooting star at the Bauhaus, lasting one year; however, it profoundly impacted her life. "It is tempting to think that all a successful designer needs are talent and determination. But they're not enough when gender, geography, genre, and timing conspire against you, as they did for Margarete Heymann."[6]

The New Bauhaus

In 1937, the forward-thinking German school—The Bauhaus—opened the iconic institution in Chicago, incubating new industrialized art in America. Now a new Bauhaus is founded on American soil and the bearer of a new civilization whose task is simultaneously to cultivate and industrialize a continent. It is the ideal ground on which to work out an educational principle that strives for the closest connection between art, science, and technology—Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, founder of the American Bauhaus. After a tumultuous decade, "the clash between design for the sake of creative exploration and the relentless demand for the next consumer product"[7] took its toll on the prodigious school. Chicago wanted the Bauhaus to bring innovation and boost local industry and commerce. However, the Berlin school's eclectic design and intellectual freedom were ahead of Chicago's traditional business interests during the 1930s.

America has entered the fourth industrial revolution and still embraces the spirit of the Bauhaus. Companies such as Apple have carried on the simplistic yet utilitarian design of their products. The pioneering approach to design can now be seen in every object we touch; from the "teapot at Target or the elegance of an iPhone," you now naturally recognize the Bauhaus impact on the design even today.[8] In Germany, the Bauhaus ended, and today The Chicago Bauhaus is now the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, carrying on the traditions of a 100-year school.

[1] Billard, J. (2018). The other art history: the forgotten women of the Bauhaus. https://www.artspace.com/magazine/ar...-bauhaus-55526

[2] Fiedler, J. (2006). Bauhaus. Konemann. (p. 19).

[3] 10 Bauhaus principles that still apply today. https://art.art/blog/10-bauhaus-principles-that-still-apply-today

[4] Weibel, P. (2005). Beyond art: a third culture. A comparative study in cultures, art and science in 20th century Austria and Hungry. Vienna: Springer-Verlag.

[5] Weltge, S. (1993). Bauhaus textiles: women artists and the weaving workshop. Thames and Hudson.

[6] Rawsthorn, A. (2009). A distant Bauhaus star. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/02/arts/02iht-design02.html

[7] Sisson, P. (2019). The new Bauhaus, a radical design school before its time. https://archive.curbed.com/2019/4/4/...gn-moholy-nagy

[8] O’Neill, M. (2019). The Bauhaus’s untold impact on everyday design on America. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/...us-100-harvard