3.8: Harlem Renaissance (1918-1930)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174418

Introduction

The Civil War ended in 1865 and hundreds of thousands of slaves were suddenly freed with the promise of participation in American life and an opportunity for self-determination. By the end of the 1870s, white supremacy restructured local and state laws, the "Jim Crow laws," taking away the right of African Americans for the promised freedom and relegating them to poverty and powerlessness. A few people escaped the legislated constrictions, but most former slaves had to work as sharecroppers. At the same time, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) terrorized the southern countryside with lynchings and intimidation. The fundamental rights of the African American population were destroyed, segregation became the law, and voting rights were erased.

In the beginning of the new 20th century, the economies in the northern and midwestern states were booming, and African Americans in the south saw the opportunity for economic advancement, jobs, education, and a more tolerant environment. Thousands of African Americans became part of the Great Migration, moving to the bigger cities in the north and west. A small region covering only a three-square-mile sector of Manhattan called Harlem developed into a significant location for African Americans moving from the south, people determined to build a new life and identity. Part of the migration included people of all backgrounds, talents, and abilities. Harlem became a major cross-disciplinary artistic center of African American artists, writers, and entertainers, developing one of the country's most critical cultural movements—the Harlem Renaissance. People in other cities also participated in the movement, but its heart was Harlem. The poet Langston Hughes wrote, "…artists who create now intend to express our dark-skinned selves without fear or shame."[1] During the period of the Harlem Renaissance, Harlem was known as an epicenter of American culture. "The neighborhood bustled with African American-owned and operated publishing houses and newspapers, music companies, playhouses, nightclubs, and cabarets. The literature, music, and fashion they created defined culture and "cool" for blacks and whites alike, in America and around the world."[2]

With the end of the 1920s and the stock market crash in 1929, the Great Depression brought an end to prosperity throughout the country and Harlem. The renaissance and culture developed in Harlem expanded worldwide, changed the perception of African Americans, challenged the racist stereotypes of southern Jim Crow, and illuminated the talents and capabilities of the people living in Harlem and other cities.

Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas (1899-1979) was born in Kansas, his mother was an amateur artist. While working multiple different jobs, he also graduated from the University of Nebraska with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. He wanted to go to Paris to study, stopping in Harlem on his way where he remained. Douglas started as a landscape painter and muralist and was influenced by the other movements of the day. He studied Cubism's fractures and fragmented images, the bright colors and stylization of graphic designs, and the masks and sculptures of Western Africa. His paintings culminated in his investigation of art styles, and Douglas became known as one of the major inspirations of the new Harlem Renaissance art. He traveled extensively and taught at universities about African American history, experiences, and art.

Douglas developed different methods and styles, integrating techniques he learned painting portraits as a muralist and an illustrator combining them into an abstract style depicting African Americans in music, poetry, and action. He incorporated the concepts of Cubism with lines and planes, the female figures usually positioned as African dancers or crouched in position. His color range was limited to greens, mauves, and brown with black forming the darker regions. He generally represented figures with darker tones, the silhouettes depicting African American social lives and struggles. Let My People Go (5.8.1) demonstrates his flat style, the figures in silhouette. Douglas' work is similar to the story of Moses leading the Israelites from Egyptian captivity, relating the concept to the oppression of the African Americans. The painting was rendered in his traditional tones of mauve and yellow gold.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Let My People Go (1935-39, oil on Masonite, 121.9 x 91.4 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Let My People Go (1935-39, oil on Masonite, 121.9 x 91.4 cm) Public DomainAspiration (5.8.2) contains multiple symbols; the star represents the North Star, the guiding light for escaping slaves. The outlines of pyramids define the contributions of African civilizations as the two figures stare upwards at the city as they aspire to achieve future progress. The painting belonged to the set of four paintings for the "Hall of Negro Life" at the Texas Exposition in 1936, only Aspiration and Into Bondage survived.

William Johnson

William Johnson (1901-1970) was born in South Carolina before moving to New York City to attend the National Academy of Design. He moved to France to work, marrying a Danish artist and living in Scandinavia, influenced by their folk art. When Johnson moved back to the United States, he taught in Harlem. During this period, he studied the cultures and traditions of different African Americans, creating paintings using the simplicity of the folk-art style. Johnson painted images of ordinary people in both urban and rural settings, from working the fields to entertaining. Unfortunately, in 1942 the building where his studio was located burned. He lost some of his artwork, a tragedy followed by the death of his wife. A few years later, he was diagnosed with a debilitating mental disease and spent the next twenty-three years of his life in an institution, dying penniless. His work had been placed in storage and was almost destroyed while he was in the institution because he could not pay the fees for storage. Fortunately, the Harmon Foundation stepped in, gathering over 1,000 pieces of Johnson's artwork and donating them to the Smithsonian.

Three Friends (5.8.3) is a portrait of well-dressed women painted in Johnson's simpler folk-art style. Something caught the attention of the women as their eyes are all looking intently in the same direction. He used bright colors to paint each person's well-coordinated outfit, including their hats, a common accessory in this period. Johnson used simple geometric shapes.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Three Friends (circa 1944-45, screenprint on paper, 40.3 x 29.5 cm) Public Domain

In Street Musicians (5.8.4), the two men are entertaining with the typical instruments, a guitar, and violin, the light brown of the instruments against the darker browns. The guitar player has a light blue jacket, the only major opposing color in the painting. The nearby fire hydrant suggests they are playing on a street corner in front of a lighter wall. Both musicians are playing left-handed, a possible reversal by the printing process, or maybe they were both left-handed.

Sowing (5.8.5) might represent the time Johnson spent in South Carolina as a child. The man is plowing through the red-brown iron-suffused dirt, and the woman holds the bag of seeds, carefully releasing each one, an indication of the importance of the potential of each seed. The representation of the house is small, a view of poverty and limited resources. In all of the paintings, Johnson successfully used each person's eyes to portray the emotion of the scene. The three women are tense, staring at the unseen, the musicians appear insecure and worried and the farming couple seems tired, worn out by the arduous task of hand plowing. Johnson uses bright contrasting colors and positions the figures in emotional situations while the eyes complete the story.

Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) was born in New Jersey, where his parents and siblings moved from the rural areas of the south. In his after-school art and craft program, the teacher recognized his ability to draw patterns with crayons. He continued working and attending different art schools, including the Community Arts Center led by Augusta Savage, where he met his wife, also a painter. He spent decades documenting the African American history, experiences, and current concepts of life, including civil rights. His work included paintings, prints, large murals, and illustrations for books. When he moved to Seattle in 1971, he taught at the University of Washington for several years, demonstrating his use of visual language to describe and create images of the human condition.

The major masterpiece of Jacob Lawrence was a series of sixty panels depicting the Great Migration, the movement after World War I of almost a million African Americans from the restrictive southern states to the industrial opportunities of the north and west. The subject matter was broad, a complex, and challenging project, trying to incorporate the emotional journeys, the hopes, struggles, hardships, and achievements of the people in flight. Lawrence found sixty matching panels to use for the story and wrote the captions and descriptions for each panel before he started painting. He wanted the panels to tell a story, unified by theme and repetitive symbols with color bringing visual unity. Lawrence covered the panels with a layer of gesso and used casein tempera for the color. He mixed his dry pigments because he had so many panels to paint, and he wanted the color to be uniform throughout the work. Lawrence did not combine colors, only used the pure form to eliminate the variation between panels with a constant palette of oranges and yellow contrasted with blue-green and gray-browns. Lawrence laid all the panels out, and starting with black; he applied one color to all the panels before moving to the next color, working from dark to light. His style was based on synthetic Cubism with geometric forms and abstracted figures.

Lawrence stated, "To me, migration means movement. There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty. 'And the migrants kept coming' is a refrain of triumph over adversity. If it rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience."[3]

Each panel was numbered in a specific order. In the opening half of the series, Lawrence depicted the financial hardships, southern injustices, and migration as the second half illustrated the migrant's life in the north. Number 3 (5.8.6) is labeled "From every southern town migrants left by the hundreds to travel north." The people are resolutely moving northwards, the flock of birds accompanying them. The bright blue of the sky and the freedom of the birds brings hope as the people carry their worldly belongings on the journey.

Number 45 (5.8.7) is labeled, "The migrants arrived in Pittsburgh, one of the great industrial centers of the North." People arrived by train as they viewed the smokestacks of the city. They had long packed their food when traveling to avoid restrictive Jim Crow restaurant laws, and this painting displays the basket sitting on the table. Fried chicken, biscuits, cornbread, and other traditional southern foods were also brought to the north, food that became integrated into the cuisine of the north.

Number 53 (5.8.8) is labeled, "African Americans, long-time residents of northern cities, met the migrants with aloofness and disdain." The couple in the painting are dressed for an evening of entertainment. The woman's clothing is depicted with swirls bringing the illusion of movement from the feathers of her cape, the man dressed elegantly, both portraying their wealth. They were probably long-term residents in the north, not part of the rural influx from the south.

Number 59 (5.8.9) is labeled, "In the North they had the freedom to vote." The people are waiting to vote, one of the most restrictive parts of the southern Jim Crow laws constraining their rights as a citizen.

Laura Wheeler Waring

Laura Wheeler Waring (1887-1948) was born in Connecticut; her family ancestors had been active in anti-slavery events, her father a minister, her mother, an artist, and a graduate of Oberlin College. Waring graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1914, where she received a scholarship to study at an academy in Paris. However, her time in Paris was cut short when World War I started, and she returned to the United States. Waring married her husband, who was a university professor. After the war, she went back to Paris and enrolled in one of the academies, a time she started to paint portraits. Her style changed, becoming more realistic with vibrant colors. Her artwork focused on portraits of prominent African Americans who achieved success across multiple disciplines and illustrated numerous magazine covers and articles. In addition to pursuing her work as an artist, she also taught school during her long career.

One of her first successful portraits was of Anna Washington Derry (5.8.10), an older woman who lived at the school in Cheyney where Waring taught. The painting earned her $400 and a gold medal from the Harmon Foundation, at the time, the only woman to receive the award. The Harmon Foundation commissioned her to paint a series "Portraits of Outstanding American Citizens of Negro Origin."[4] This set of portraits earned her the most recognition, and they toured the United States to fight stereotypical beliefs and demonstrate the careers and successes of the people in the portraits. The series also included work by Betsy Reyneau. Some of the paintings in the series included: Alma Thomas (5.8.11), a fellow artist; W. E. B. Du Bois (5.8.12), a writer, historian, civil rights activist, and a founder of the NAACP; and James Weldon Johnson (5.8.13), a writer and civil rights activist. The original paintings were completed in color.

Archibald Motley

Archibald Motley (1891-1981) never resided in Harlem. He was born in New Orleans and moved to Chicago, attending a predominantly white prep school and then the Art Institute in Chicago. His training was classical, which he was forced to use while secretly painting more modern images he kept hidden. In 1929, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. He went to France to study, mainly studying the old masters and genre works, gaining an understanding of how black bodies were stereotypically portrayed in paintings, inspiring him to change the way racial representation was expressed. Early in his career, he was successful and was the first African American to exhibit in his one-man show in New York City. In 1920, he focused on portraits, shifting in the 1930s to non-traditional urban settings representing the activities and lives of the African American community.

Motley was mixed-race with lighter skin color, and he struggled with racial identity all his life. As part of the struggle, he also studied the concept of skin tone gradation and its effects on society. Motley tried to paint a broad representation of blackness and its diversity, a celebratory portrayal of people and their positive plurality. In an interview with the Smithsonian Institution, he described his concepts and the problem associated with painting the wide variety of skin tones of African Americans, "They're not all the same color, they're not all black, they're not all, as they used to say year ago, high yellow, they're not all brown. I try to give each one of them character as individuals. An that's hard to do when you have so many figures to do, putting them all together and still have them have their characteristics."[5] Motley believed by painting the different skin tones; he also defined the personalities of each person eliminating stereotypes.

Motley brought his concepts and ideas of skin tones to his vibrant paintings, celebrating the jazz culture and exuberant life of the urban culture of the African Americans, quite opposite from the typical views of rustic, poverty images of blacks in the south. Nightlife (5.8.14) shows people in the cabaret, couples dancing across the painting to the music of the jukebox on the far edge, and the bartenders busy mixing drinks in front of a well-stocked bar. The lighting is unnatural, a burgundy tone illuminating the lively scene.

Cocktails (5.8.15) is a very different scene; the women sit around the table as drinks are served, talking and laughing. Alcohol was illegal at the time; speakeasies were the typical establishment. The warm palette in the painting is enlivened with an abundance of reds and pinks. The women are all depicted with different skin tones, as the much darker-skinned waiter is serving them, the diversity of color, and economic status.

Blues (5.8.16) is considered an iconic painting of the Harlem Renaissance. Although Motley did not live in Harlem, he did live in Paris, and the painting probably reflects some of the scenes he saw there. The nightclub is full of people dancing, smoking, and playing instruments. Different vibrant colors accent the image; the gold trombone, a red dress, yellow pants, a gray hat, a white hose, the brown suit, and a wide variation of skin tones. Motley flattened the figures into stylized versions with curved lines.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=1075&height=850)

His Self Portrait (5.8.17) was painted early in his career after he graduated from college to create a positive image of a poised, capable, young artist. Motley wore a dark suit jacket with the white-collar in high contrast, his tie held with a diamond horseshoe pin demonstrating assurance and success. He is holding a brush and palette denoting his talent as an artist. Motley wanted the painting to exhibit his success and to show the perception of a young African American man as a positive image.

James Richmond

James Richmond (1901-1989) was born in Mississippi; his father died when he was a few months old, forcing his mother to work as a dressmaker. Barthé's mother kept him entertained with paper and pencils while she worked and he learned to draw. He continued to draw throughout school until typhoid fever forced him to withdraw. When he recovered, he worked as a houseboy for a wealthy family who exposed him to a wide range of art and culture. At twenty-three, a local priest raised money for Barthé to attend the Art Institute of Chicago, training as a painter. He did have to take an anatomy class using clay to develop a three-dimensional form, an experience proving to be a turning point and a pathway to a career. When he moved to New York City, he could not afford to pay for models, so he went to the theatre, and studied performers and their movements to create sculptures based on his visual memory. He was very successful, receiving multiple awards and noticed as a leading modern artist during this period. He created sculptures of famous people, built numerous public works projects, and received extensive recognition throughout his life. Barthé sculpted in a realistic style producing sculptures of African Americans seldom seen before.

When Barthé was at the Art Institute in Chicago, he focused on developing expressive poses, giving the body movement. He watched boxing matches by the Cuban "Kid Chocolate," the inspiration for his sculpture of the Boxer (5.8.18). The lean, muscular boxer is posed on the balls of his feet, his arm ready for action. Barthé characterized the boxer as moving with the grace and movement of a ballet dancer.

Blackberry Woman (5.8.19) depicts an African American woman carefully balancing a basket as she walks to the market. The image was probably a familiar sight Barthé saw as a young man in Mississippi with her bare feet and simple dress. He named the sculpture after the title of a Wallace Thurman book about discrimination against darker-skinned women. Barthé always wanted to visit Africa, stating, "I'd really like to devote all my time to Negro subjects, and I plan shortly to spend a year and a half in Africa studying types, making sketches and models which I hope to finish off in Paris for a show there, and later in London and New York."[6] However, he was never able to travel to Africa.

Booker T. Washington (5.8.20) was an educator, writer, and one of the foremost political leaders at the turn of the century. His father was white and unknown, so he gave himself the last name of Washington when he was in school. Barthé made the detailed bronze bust of him as part of the series about prominent African Americans.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877-1968) was born in Philadelphia; her mother was a hairdresser and a wig maker, and her father a barber. Her parents encouraged the family to visit museums, play musical instruments, sing and draw. When Warrick graduated from high school, she went to Philadelphia College of Art to study sculpture and even won first prize for her modeling work. As with many artists, she traveled to Paris to further her education, eventually working with Auguste Rodin as she developed a style of building expression and emotion into her work. When Fuller returned to the United States, she received a federal art commission, one of the first given to an African American woman. In 1901, she married a psychiatrist, and they moved to Massachusetts and faced an uprising from neighbors who did not want them to move into the suburb. Within a year, the building she stored her sculpture work from Paris was destroyed in a fire.

After a long hiatus and having three sons, she returned to sculpting and adopted African American-based concepts. Ethiopia Awakening (5.8.21) was cast in 1922 as a full-sized bronze sculpture for a New York City exhibit. The female, emerging from her mummy-like wrappings, wears an Egyptian royalty headdress, her face defined as an African woman. The upper part of the torso appears to be reaching upward, the emergence of the African spirit.

One of the most significant works by Fuller is the sculpture of Mary Turner (As a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence) (5.8.22). The work memorialized Mary Turner, who was brutally lynched when she was eight months pregnant. In the sculpture, she is holding an infant, the grasping hands around the base. Turner's husband had been lynched, and when she denounced the lynching, the mob took her and brutally hung her upside down on a tree where she and the infant died. The rough-hewn bronze on the bottom half shows the viciousness of the mob as she leans away from them. Fuller was a pioneer in depicting a lynching scene and continued creating many memorable sculptures.

Augusta Savage

Augusta Savage (1892-1962), born in Florida, was creative as a child using the local natural red clay to make small sculptures and animals. Her father was a minister who strongly disapproved of her making clay figures, claiming they were graven images. She recalled, "My father licked me four or five times a week and almost whipped all the art out of me."[7] Fortunately, a principal in the high school recognized her talent and had her teach a clay class, generating in her a love for teaching and art. She married at a young age and had one child, her husband dying right afterward. A few years later, she married again, divorcing after a few years. Savage continued to model clay figures, gathering prizes and commissions. By 1921, she left Florida for New York City and attended Cooper Union, graduating in three years. Savage applied for a summer art program in France and was rejected because she was a black person, a rejection spurring her interest in civil rights. She married again after graduation, her husband dying the next year. Although Savage received a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, she could not afford the living expenses or travel costs and had to turn down the opportunity. Savage was finally able to go to France in 1929 with the help of fundraising parties in Harlem and other support groups, enabling her to study, research and exhibit in Europe. When Savage returned to the United States, she established a studio for artists, facilitating education and support for many future artists.

Most of Savage's work is in clay or plaster, bronze an expensive medium and usually unaffordable. Gamin (5.8.23) was an image of a young boy whose personality is captured in his expressions and demeanor. His crumpled cap sits jauntily angled to one side as he tilts his head. His deeply set eyes and broad facial features give the boy a slightly defiant, appealing look. The boy was representative of the Harlem Renaissance concepts, a streetwise child defined by his African American heritage. The bust of the boy was made of painted plaster.

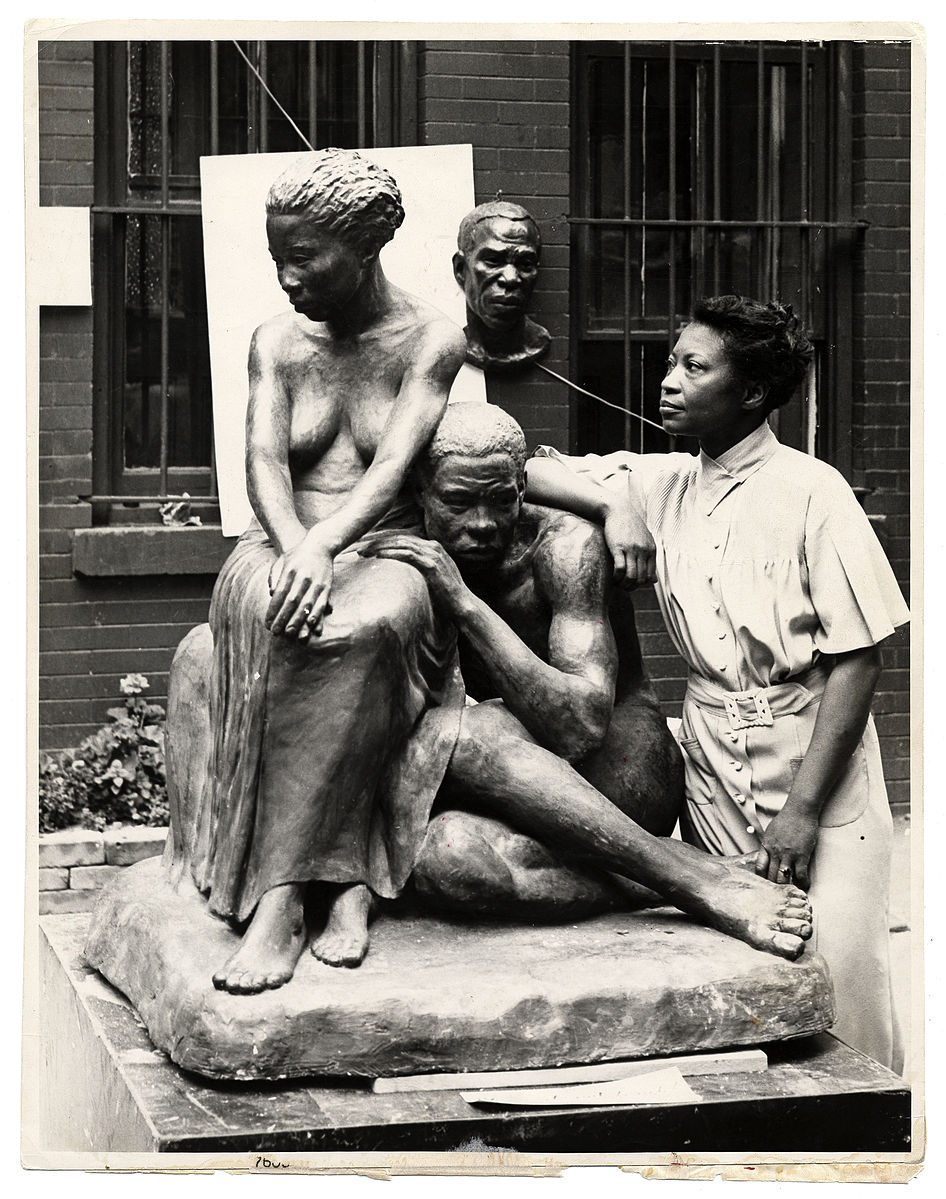

Realization (5.8.24) only exists in photograph form. The project was commissioned by the Work Projects Administration in 1938, and its location is unknown. She made most of her work in clay and plaster, and unfortunately, a significant amount of her work is lost because it lacked the permanency of metal. Savage did not leave any notes about the work Realization, which appears to be about slavery and the practice of splitting family members to sell to different slave owners, the woman's top forced off. In the photograph, Savage almost appears to be joining the trio, supporting them in their time of agony.

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\): Augusta Savage posing with her sculpture Realization (Photograph 1938 26 x 21 cm) Public Domain

The end of the Harlem Renaissance started with the depression and the stock market crash in 1929. Some elements continued until the end of prohibition in 1933, and the illegal alcohol so plentiful in the clubs was not necessary for the white patrons. Many influential and successful Harlem residents moved to find work in other places, and in 1935, after the Harlem Race Riot, the renaissance vanished. However, the time was a golden age for writers, musicians, and artists of the African American community, bringing their experiences into American culture.

[1] Hughes, L. (2015). The Weary Blues, Knopf; Revised edition (10 February 2015).

[2] Retrieved from https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance

[3] Retrieved from https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series

[4] Leininger-Miller, T. (2005). "A CONSTANT STIMULUS AND INSPIRATION": LAURA WHEELER WARING IN PARIS IN THE 1910s AND 1920s. Source: Notes in the History of Art, 24(4), 13-23. Retrieved July 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23207946

[5] Shaw, C. E. (2011). The Untold Stories of Excellence: From a Life of Despair and Uncertainity to One that Offers Hope and a New Beginning, Xlibris Corp., p. 487.

[6] Gates, H. L. Jr. (2009). Harlem Renaissance Lives, Oxford University Press, p. 38.

[7] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artist/augusta-savage-4269