9.8: Manga/Anime (1950-)

- Page ID

- 209051

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Manga/Anime are graphic art appearing a comics or graphic novels. The concept originated in Japan and is based on early Japanese styles. Manga may appear as comics or cartoons and printed in magazines and books. Published manga stories are generally drawn in black and white, although some artists do incorporate colors. Anime is closely associated with manga. Anime was based on either hand-drawn or computer-generated styles of animation. Many manga books and comics were transformed into anime images and animated in games or videos. Manga incorporates multiple subject matters, including action, sports, crime, fantasy, history, horror, sex, science fiction, and war, as well as other topics.[1] People of all ages read or view manga; however, some work may not be proper for children, while others are geared toward children. "Comics accounted for 27 percent of all books and magazines published in Japan in 1980; the more than one billion manga in circulation yearly amount to roughly 10 for every man, woman, and child in Japan."[2] The plot is laid out in single episodes of a serial story and printed. Popular and well-liked stories are frequently made into animated films. Manga grew immensely popular in Japan after 1950 with two different types; shōnen manga was based on subject matter for boys, and shōjo manga was created for girls.

Initially, most manga comics were made by men and based on shōnen manga subjects. At the beginning of the 1970s, a group of female artists called the Year 24 began creating shōjo manga to expand the themes and add complexity and social constructs to the artwork. Early shōjo stories for girls covered simple romantic or sentimental stories. When shōnen stories for boys found new innovative directions like fantasy or science fiction, girls' stories stagnated. The Year 24 group began to create female characters in their stories. Their themes covered politics, sexuality, female heroics, and philosophical ideas. The artists of Year 24 also started developing specific aesthetics associated with the shōjo stories. Their figures were elongated, their eyes sparkled, and their hair flowed. They also used very delicate linework against abstracted backgrounds and decorative embellishments. The artists used flowery icons to emulate different emotions; for example, "trees are full of life, and flowers are in bloom to represent beauty, while they change to lifeless with petals flowing in the wind to express grief and sorrow."[3] Later artists expanded on the themes and brought shōjo stories about female heroes closer to the exploits of male heroes. The video is based on a discussion of shōjo manga and its development. Artists in this section include:

- Rumiko Takahashi (1957-)

- Hiromu Arakawa (1973-)

- Machiko Hasegawa (1920-1992)

- Keiko Takemiya (1950-)

- Naoko Takeuchi (1967-)

- Momoko Sakura (1965-2018)

- Hideko Mizuno (1939-)

This week, in COMICS CRASH COURSE - EPISODE #43, "Shoujo Manga", we look closely at manga made for women and girls--shoujo manga. We spend an extra moment or two looking at the revolutionary women of the Year 24 Group

Rumiko Takahashi (1957-) born in Japan and was interested in manga as a child. In college, she studied Japanese literature and drawing, including designing doujinshi (fan comics). After a year, Takahashi joined the school of Kazuo Koike, who helped develop the methods of quickly producing manga pages. Takahashi also learned about the importance of each character in a story and how to integrate them into the theme. She first published her work at age twenty and developed her lifelong themes. Takahashi used humor and an unpretentious cartoony style for her work. She became known for her "aliens, panty thievery, love polyhedrons, monsters and spirituality, and puns. Lots of puns…"[4] In 2018, Takahashi was the first manga female artist inducted into the Will Eisner Comics Hall of Fame, the Oscars-like award for comics.

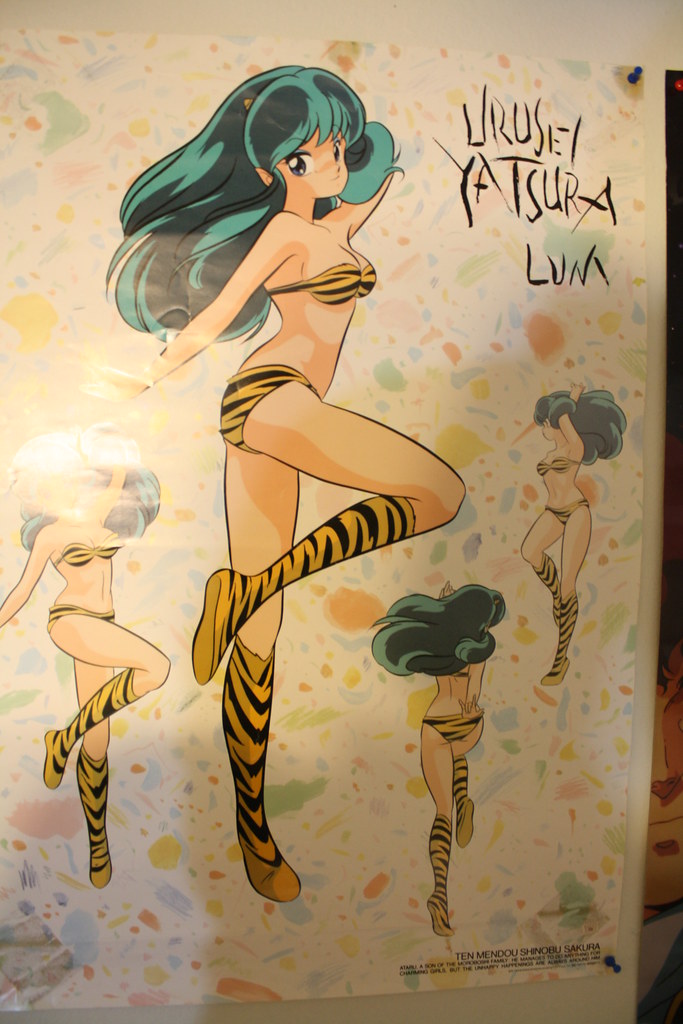

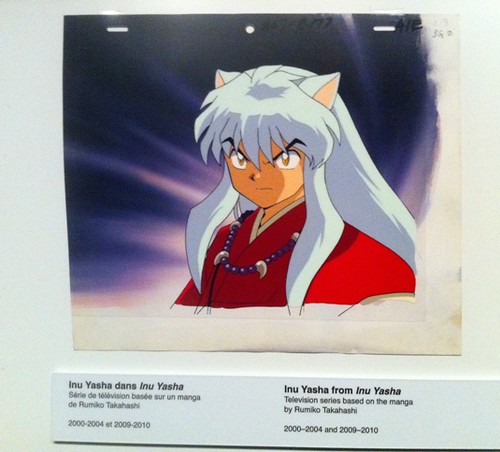

One of Takahashi's most popular series was Urusei Yatsura. She created thirty-four volumes for the series based on Japanese mythology and culture with heavy use of puns. The series was eventually made into a television series. Urusei Yatsura started Takahashi's successful career and was considered one of the best-selling manga series. The title is roughly translated into English as "Those Obnoxious Aliens."[5] One of the main characters was Lum (9.8.1), a princess of Oni, an alien planet whose people want to take over Earth. Lum was characteristically dressed in tiger-striped boots and a bikini, her hair traditionally green. Lum is exotically beautiful and generally relaxed; however, she shoots powerful electric charges when angered. Lum is still a very popular image in Japan and is used in electronic media, prints, advertising, and commercial merchandise. Another significant series by Takahashi is Inuyasha. One of the main characters is a fifteen-year-old girl who finds herself in another period of time. She meets the other central character, Inuyasha (9.8.2), who is half dog and half human. In this series, Takahashi deals with more violent content between the characters. The successful series was made into videos, games, and other merchandise.

Rumiko Takahashi is arguably the most influential mangaka of all time, and she can be heavily credited with helping bring manga and anime to the western world. We've loved covering her shows like Ranma 1/2 and Inuyasha, but we finally wanted to spotlight Rumiko Takahashi herself. Her story from childhood to mangaka powerhouse isn't what you might expect. She wasn't a prodigy; she wasn't creating manga at the age of 3. But she was dedicated and passionate about what she loved, and it shows through her entire life.

Hiromu Arakawa

When Hiromu Arakawa (1973-) born in Japan and was in high school, she also had to work for the family dairy farm. During this period, Arakawa took oil painting classes and drew dojinshi manga for a magazine. She always wanted to be a manga artist and moved to Tokyo in 1999 to work with different publishers. Stray Dog was her first solo artwork, for which she received an award. However, Arakawa is best known for her series Fullmetal Alchemist. She also had another successful series, Silver Spoon, which was more realistic with less fantasy. Arakawa still lives in Tokyo and is married with three children.

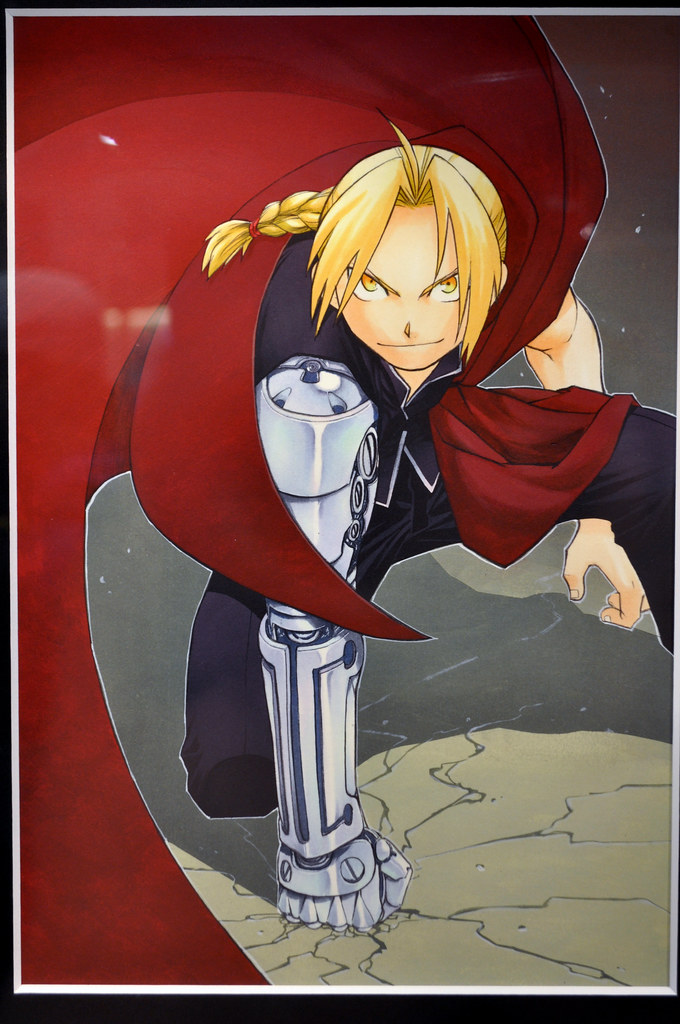

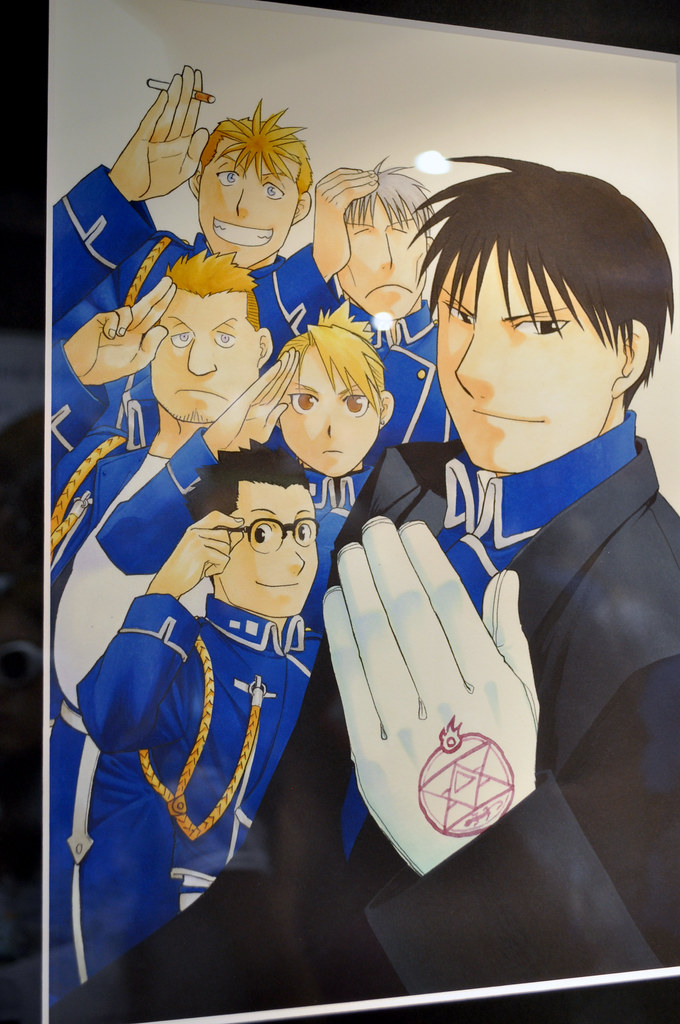

Fullmetal Alchemist has a complex theme and significant violence and brutality. The strong and powerful characters move through death and resurrection scenes, retribution, and bloody outcomes. The story is based on the practice of alchemy and the ability to lose body parts, hoping to restore themselves to normality. Edward Elric (9.8.3) and Roy Mustang (9.8.4) are two characters. Arakawa creates passion, feelings, and emotion in the characters' faces. Each of the faces in the images portrays different looks and intensities. The theme and plot of the story are balanced despite the tragedy and aggressive action.

An interview in 2017 with Hiromu Arakawa, author of the Japanese famous manga Fullmetal Alchemist. Her first appearance on TV.

Machiko Hasegawa

Machiko Hasegawa (1920-1992) born in Japan and was one of the original female manga artists when she created her comic strip called Sazae-san. The comic was first published in national circulation in 1949 and continued until 1974 after she retired. The cartoons were reprinted digest comics until the end of the 1990s. As a child, Hasegawa drew comics. She never married and lived with her older sister. The two sisters even started their own publishing company to publish some of Hasegawa's comics. Hasegawa received the Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon in Japan, the first female manga artist to be honored with the award.

Sazae-san was a comic strip based on the life of an imaginary Japanese housewife. Sazae-san started as a comic strip, was a radio and animated series, and is still in production today. In the story, the mother is named Sazae-san and lives with her husband, children, and parents. Because the series was one of the early illustrations, the series followed traditional concepts and themes. The comic has no violence or magical creatures. However, it is well-liked by children and still thought acceptable by adults. The characters were very popular, and these statues (9.8.5) are in a park. The video discusses Hasegawa's career and shows some of the comics.

"Sazae san" is a famous yonkoma manga series, then adapted into a cartoon series, written and illustrated by Machiko Hasegawa. In Japan it is very famous but it is not so popular abroad. This video the one on Anpanman is meant to spread knowledge on some anime/manga very popular in Japan but mostly unknown to many persons.

Keiko Takemiya

Keiko Takemiya (1950-) born in Japan and was part of the Year 24 group. She was interested in art and writing and applied for different contests in high school. Takemiya even received an honorable mention for one entry. As part of the Year 24 group, Takemiya pioneered a new shōjo manga genre illustrating love between men. The genre became known as "boy love" or shōnen-ai and was probably the first recognized male-male kiss in shōjomanga. Takemiya was considered "one of the first successful crossover women artists,"[6] creating shōjo and shōnen manga. Kaze to Ki no Uta and Toward the Terra are Takemiya's best-known works. Both stories and some of her other works have been translated into video. Takemiya taught at Kyoto Seika University, became Dean of the Faculty of Manga, and then the university's president. One of her goals at the university was to use digital technology to preserve manga manuscripts accurately.

Toward the Terra was one of Takemiya's best-known works. As part of the future, the earth was environmentally destroyed, and people were left to create a living place elsewhere. A supercomputer controls the population, even how many children are born. A new advanced race emerges named the "Mu." Their dream is to find earth and return. Because the number of children allowed is created separately in vitro, the Mu try to find all their offspring before returning them to Earth. The series was top-rated and translated into multiple languages (9.8.6), made into a movie and a TV series. In the first video, Takemiya is interviewed about Toward the Terra. The second video is a short clip from the television series.

Interview with Keiko Takemiya, creator of Towards the Terra (Japanese with English subtitles)

Naoko Takeuchi

When Naoko Takeuchi (1967-) born in Japan and attended high school, she belonged to the astronomy and manga clubs, two experiences she later used in her work. Takeuchi studied chemistry at the university because her father thought scientific pursuits led to a better career. She graduated with a degree in chemistry and was a licensed pharmacist in Japan. However, after graduating, Takeuchi submitted some work to a publisher who printed it. Takeuchi received an award for the best new artist for her initial submission. Takeuchi married in 1999, and they have two children. She continued working on other projects but wanted to create something more aggressive based on outer space and incorporating girl fighters as superheroes. Her series Sailor Moon was an immediate success. Takeuchi continued developing multiple series while moving into anime and animated some of her work, including Sailor Moon. Eventually, Takeuchi became the production manager for future films, and some films are still based on the concepts of her successful work, Sailor Moon.

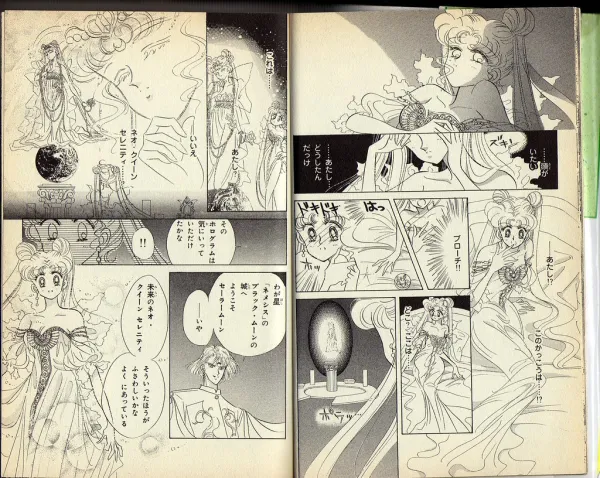

Takeuchi used names from her own family as characters in Sailor Moon. She also used her chemistry background; some characters are named based on different minerals or gemstones. Takeuchi even used her neighborhood as the primary site for the characters. The girls in the series wore clothing like sailor suits, a standard uniform for girls in Japan. The main character, Usagi, was not athletic or a great student. After encountering a cat, she starts a journey and develops mental strength and an inspired heart, a girl who supports her friends as the new Sailor Moon. Two characters are lesbians, and Takeuchi wanted to demonstrate how girls can also have a romance. The series has been widely printed and made into movies, video games, and even stage musicals. Takeuchi even wrote songs for the movies. Sailor Moon is one of the most popular and well-liked manga series. The images for Sailor Moon (9.8.7) demonstrate the detail Takeuchi used when she created the series. The characters have the typical oversized eyes, long flowing lines, and details in specific places. The first video is an interview with Takeuchi and how she works.

This is the story of Naoko Takeuchi, a mangaka who created a Shojo that would forever change the world. Sailor Moon has and continues to impact the lives of millions, and Takeuchi worked extremely hard from a young age to achieve her goals.

Momoko Sakura

Momoko Sakura (1965-2018) born in Japan and has kept her life relatively private, and little has been documented. She started her career as an artist in 1984 in high school, and her major successful project was first published in 1986. Chibi Maruko-chan was based in Sakura's neighborhood as a child living in suburban Japan. Sakura also created more surrealistic fantasy, including characters and stories for video games on Nintendo and the Xbox. Based on the successful manga version of Chibi Maruko-chan, Sakura made the series into an anime series. As part of the series, she included music that influenced the musical landscape in Japan.

Chibi Maruko-chan was based on simple everyday activities centered around the young girl Maruko and her family. The girl has a series of events happen as she is labeled a troublemaker. The young girl and her friends are involved in situations they encounter and solve different problems. Maruko (9.8.8) has a sister, parents, and grandparents as the main characters; the images are theoretically based on Maruko herself. Sakura used a "face fault" technique for the series to display reactions and emotions in situations. Manga standards developed a specific type of emotional display. Maruko's family shows manga characteristics in their faces, especially in the eye definitions, the lines for the mouth and noses, and the child-like look of their faces. The manga series was so successful the story was made into a long-running television series, games, films, and multiple types of merchandise (9.8.9). The manga series was one of the best-selling series in Japan. The video is an episode from the series.

The animation of Chibi Maruko Chan English dubbed version episode 808, "Maruko Goes to a Sushi Restaurant"

Hideko Mizuno

Hideko Mizuno (1939-) born in Japan and grew up without a missing father after World War II and a mother who died when Mizuno was young. Her family was a grandmother and an uncle. A bookstore near her house supplied her with books that grabbed her imagination. Mizuno loved manga when she was a small child, and by the age of twelve, she was entering magazine contests with her ideas. When she was entering high school, Mizuno received an honorable mention for one of her entries. A publisher saw her work and ordered some work for a magazine. Mizuno was only fifteen years old at the time. Her first work was based on a girl, and her pony was based on a "tomboy" concept for the heroine. Mizuno went to Tokyo to continue working and developing new ideas for shōjo manga. Initially, most of the manga for girls focused on a mother-daughter affiliation. Working with other women, Mizuno introduced the concept of romantic comedy. Harp of the Stars was her first manga based on romance and one of the first of this style to be made by a woman. She was also known for the first shōjo manga with a boy as the protagonist, historical drama, sexual scenes, and her unusual story based on rock music and civil rights, Fire. Mizuno was considered a pioneer, a groundbreaker, and influential for the next generation.

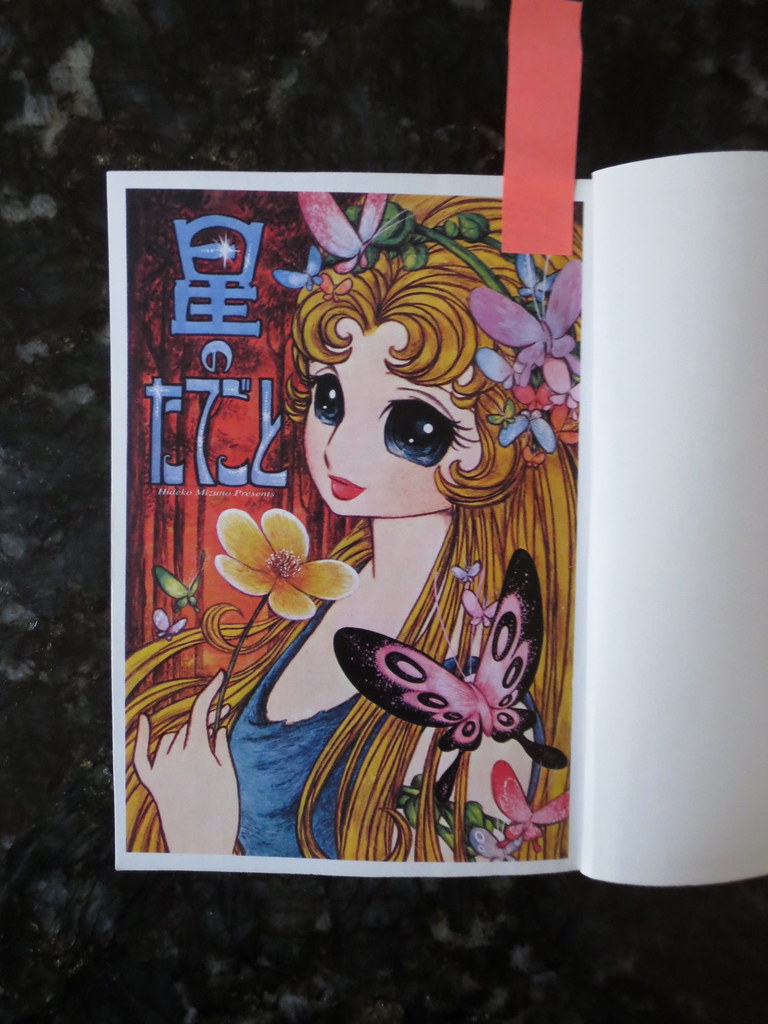

When Mizuno wrote Harp of the Stars or Hoshi no Tategoto, she broke the taboos of romantic stories for shōjo magazines. Mizuno stated, "In our school days, boys and girls played apart even though we attended the same school. Despite our interest in each other, I thought it was strange that we couldn't be closer. Even marriage was all about arrangements, not love. All of the world's great stories and movies show beautiful romance. So, I thought it would be good to do the same in manga."[7] In the story Harp of the Stars (9.8.10), the young girl is the daughter of a count. A group of intruders enters the room, a harpist rescues the girl, and the romance begins. The beauty of butterflies and flowers surrounds the girl. The video contains an interview with Mizuno.

Manga master Hideko Mizuno, shôjo manga pioneer, tells us how he managed to make her debut and the role of "manga god" Osamu Tezuka in it all.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.mit.edu/~rei/manga-list.html

[2] Schodt, Frederik L. (1985). "Reading the Comics". The Wilson Quarterly. 9 (3): 64. JSTOR 40256891

[3] Retrieved from https://hakutaku.us/2018/07/17/the-year-24-group/

[4] Retrieved from https://islandlibrarian.blog/2018/07...ll%20of%20Fame!

[5] Retrieved from https://archive.animeigo.com/liner/o...tv-series.html

[6] Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20160407...a-stories.html

[7] Retrieved from https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g02029/