9.7: Photorealism (late 1960s -1980)

- Page ID

- 209050

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Photorealism is based on the concept of an image closely resembling a photograph. The artists incorporated multiple media types, including painting, drawing, or mixed media, to create the same view as a camera. As one of the many art styles during this time, Photorealism developed from Pop Art and rejected the ideals of Abstract Expressionism or Minimalism. The camera and photography were more refined, and as the cost of colored photos became affordable, the camera became popular. Photorealists used the basis of the actual photos for information and tried to recreate the image. The artist had to be precise and generally copy the outlines by projecting the photo onto the canvas or using traditional grid lines. The results were detailed and precise.

The Photorealists emphasized careful planning and precise craftsmanship in their approach to art. They were predominantly active in the United States and created works of art that often depicted everyday objects or familiar scenes and portraits. These paintings had a nostalgic feel that evoked a sense of familiarity and comfort in the viewer. The Photorealists preferred to work on a large scale, utilizing paint or airbrush techniques to achieve their desired level of realism. In contrast to other artistic movements of the time, the Photorealists emphasized the creation of smooth surfaces that did not reveal visible brushstrokes. This approach was essential in achieving a more photographic appearance in their work. The Photorealists were dedicated to their craft and produced highly valued artwork for its technical brilliance and attention to detail. Artists in this section:

- Audrey Flack (1931-)

- Martha Rosler (1943-)

- Shirin Neshat (1957-)

- Vija Celmins (1938-)

Audrey Flack

Audrey Flack (1931-) was born in New York City and received her bachelor's degree in art from Yale University. Like many artists at the time, Flack's work followed the concepts of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. During the 1960s, she moved to a photorealistic style working with Richard Estes and Ralph Goings. Flack used photographs as her model for the painting; however, she did not paint one entire scene. She incorporated different images and ideas based on an integrated concept. Some parts of the painting might have portraits, and other components included inanimate objects. Flack was the only woman in the Photorealist movement. She discarded their ideas of cars, trucks, or empty street images and instead wanted to add more emotional and symbolic imagery. Flack also brought a more feminine perspective to the works, using idealized symbols overlaid with assertive female objects. Although she was criticized for her feminist subject matter, critics often calling her work vulgar, Flack remained committed to her ideals.

Marilyn (Vanitas) (9.7.1) is one of a series of oversized paintings Flack painted and focused on the realistic presentation of the layered symbols of contemporary and historical feminism. She had a photographer capture each object with a camera and then make 35mm slides, combining the images for the painting's base. The photograph of Marilyn Monroe was the focal point. Most high-contrast objects are rounded, following concepts of female curves; only the photograph of the children has the hard edges of the rectangle. Many objects reflect light with a noticeable gloss, while the mirror reflects Monroe's face. The cosmetics are elements Monroe was expected to use as other objects like the calendar or watch, indicating the passage of time. Invocation (9.7.2) demonstrates how Flack used vibrant, saturated colors to paint a compilation of objects and form a unifying composition. She stated, "My colours are bright, my subject matter passionate and humanist, the opposite of cool and restrained, the opposite of the other Photo Realists''."[1] Flack used the skull to represent the fragility of life and the inevitable death. Flowers and candles also decay with time

Martha Rosler

Martha Rosler (1943-) was born in New York and spent her youth in California before returning to New York. She graduated from the University of California, San Diego. Rosler was a professor at Rutgers University and a guest visiting professor at other campuses. Her primary interest was photography, photomontage, and photo text. Rosler also created videos, sculptures, and especially writings. She wrote multiple books and created an extensive library and book collection for the public. Rosler was active in civil rights, women’s rights, homelessness, and anti-war efforts. She frequently collaborated with different activist groups to help accent a problem. Many people thought of her as an activist, however, she stated, “artist as activist designation is different, but it includes the artist saying that they will only be a part of projects that fit certain criteria and you shouldn’t leave the word artist out of it.”[2] Rosler also believed in the past that a dual identity concept of artists and activists prohibited acceptance as an artist. In the twenty-first century, the idea is now a badge of honor. Her early photomontage work was based on the wars and their connections to life at home.

The Vietnam War was the first time an actual war was viewed by people in their homes on daily television. Many called it the “living room war.” Rosler used multiple media of, photography, videos, and her writings to illustrate the brutality of the war. Red Stripe Kitchen (9.7.3) was part of her House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home series. The modern kitchen is an example of anyone’s home getting ready to prepare a meal. The perfect white cabinets, matching dishes, and expansive cutting board are all part of the beautiful house everyone needed. The oddity of the soldiers looking for the enemy in juxtaposition to the pristine room is a startling demonstration of how the war was a separate part of ordinary life. Rosler combined photos to make the montage. The comprehensive blood red line across the background brings the soldiers and their pathway to particular importance.

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were frequently labeled the “endless wars”; wars which brought ongoing protests. The theoretical war on terrorism dragged on with high civilian causalities and high monetary costs. As part of the Artists Against the War, Rosler recreated some of her House Beautifulphotomontages for an anti-war exhibit. To make her photomontages, Rosler used photographs and cut the parts she wanted to use. The different images were assembled to create the story, and then printed images were made. In The Gray Drape (9.7.4), the elegantly attired woman in her home unrolls a gray drape, oblivious to the scene on the other side of the window. The image demonstrated how part of the world worried about what to wear or how their house appeared while another part was isolated to the brutality of war. One woman stands in her shiny dress while the other woman holds her child, trying to shield it from the fires of war.

A conversation with Martha Rosler.

Shirin Neshat

Shirin Neshat (1957-) is an Iranian-born artist who fled the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and moved to the United States at seventeen. She graduated with an MFA from the University of California, Berkeley, moved to New York City, and worked at an independent gallery. Returning to Iran for the first time in 1990, Neshat was shocked by the social and political upheaval caused by the war. Returning to the States, she dove into her art, mixing Farsi text with photographs based on her experience in Iran. The text is from female authors during the revolution, such as poet Tahereh Saffarzadeh (1935-2008).[3] Neshat used woman’s body parts not covered by the chador or long gown. She used women’s poetry for her words because they gave voice to individuals and a woman’s sexuality hidden by the chador or veils.

"Shirin's exhibit was motivated by the series of political uprisings, now commonly known as the Arab Spring, which took place throughout different Arab countries between 2011 and 2012. The Book of Kings explored the causal conditions of power within social and cultural structures in the modern society."[4]

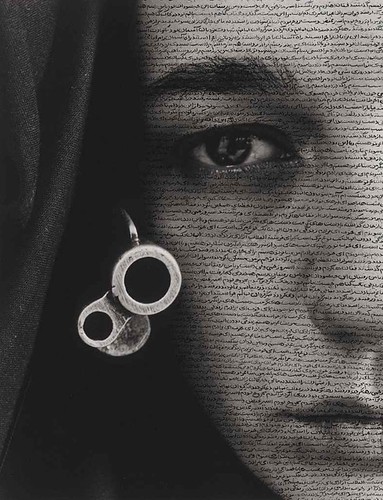

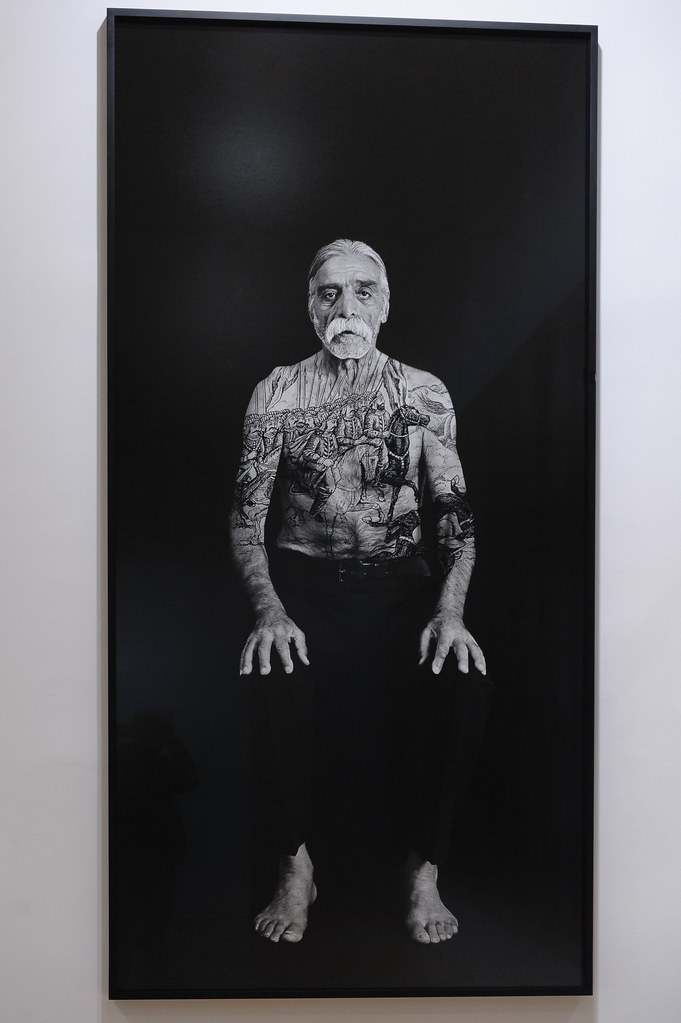

Neshat's early photographic work addressed the women's psychological experience in Islamic cultures. Exposing the issues of femininity and how women identify themselves, she captures the concepts of polemical essays. Speechless (9.7.5) is one of a group of formidable images Neshat has connected to Islamic fundamentalism. During her return to Iran, she faced a changing country, men had taken control, and the once cosmopolitan women no longer existed. Staging photographs of women in chador dressings staring right at the viewer and holding guns with text on their faces were powerful art pieces. The print Speechless is a close-up of a woman's face with the barrel of a gun in place of an earring. The women do not appear weak; instead, Neshat has portrayed them as solid and heroic despite suffering through years of social persecution. Neshat created a series entitled The Villains (9.7.6), pictures of older men with calligraphic details across their chests and arms. The text represents metaphors from the Book of Kings—a Hebrew Bible written in two books. In Bahram, the scene depicts the king on a horse leading an army of men carrying a flag across the plains into battle.

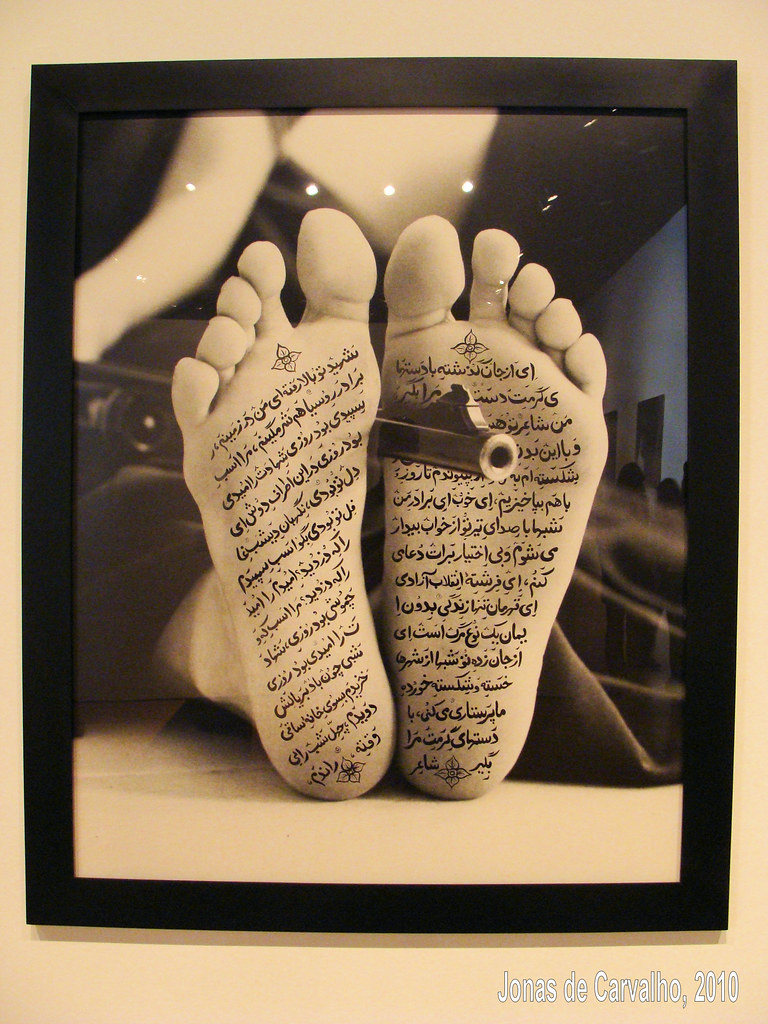

I Am Its Secret (9.7.7) is an image of a veiled Muslim woman gazing into the camera. Neshat used herself for the face of the woman. Farsi, in black and white lettering, covers her face in a circular pattern, swirling around and around. Allegiance with Wakefulness (9.7.8) depicts her feet covered with Farsi, a gun held between her feet and pointed at anyone who comes. The images are from Neshat’s series “Women of Allah,” made when she returned to Iran after the revolution. The series covered the theme of a veil, gun, text, gaze, and Farsi words. Neshat wrote, “Although the Farsi words written on the works’ surfaces may seem like a decorative device, they contribute significant meaning. The texts are amalgams of poems and prose works, mostly by contemporary women writers in Iran. These writings sometimes embody diametrically opposing political and ideological views, from the entirely secular to fanatic Islamic slogans of martyrdom and self-sacrifice to poetic, sensual, and even sexual meditations.”[5]

Iranian visual artist Shirin Neshat uses film, video, and photography to explore issues of gender and identity, focusing on women's relationships with the religious and cultural systems of Islam.

Vija Celmins

Vija Celmins (1938-) was born in Latvia. During World War II, after the Soviet invasion of Latvia, her family fled to Germany. After the end of the war, the family lived in a refugee camp before relocating to Indiana in America. At this time, Celmins was ten years old and did not speak English, so she turned to drawing to communicate her feelings. She received a degree from the John Herron School of Art, including an internship at Yale, where she met Chuck Close. She received an MFA from UCLA in 1965 and taught at some local colleges. In 1981, Celmins moved to New York City and returned to painting and printmaking. In the 1960s and 1970s, she stopped painting to focus on images made with a graphite pencil based on photographs. During the following decades, Celmins painted, created sculptures, and made different prints.

Untitled (Ocean) (9.7.9) demonstrated her attention to detail and how she developed the ocean and waves' surface, bringing the water's luminosity to the horizon. The grayness of the work is impersonal, with a neutral palette. Her laboriously made untitled series of oceans earned her early recognition. She explained, "Part of what I do is document another surface and sort of translate it. They're like translations, and part of it is fiction, which is invention."[6] Web #3 (9.7.10) is one of Celmins' monochromatic images. She used photographs as the base for the spider web. The web is a glimpse in time as captured by a camera, her work developing the translucence and fragility of the web. Celmins said she identified with spiders because they worked on something repeatedly. She became well known for her spider web, the night skies, or the unending waves. Unlike other Photorealistic artists, her work had no reference point making it impossible to determine any context or location.

How do you read a Vija Celmins painting? How do you enter a surface? Celmins walks us through the elements of her artworks and discusses the conceptual explorations that have engaged her for more than five decades.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.kingsnews.org/articles/audrey-flack

[2] Retrieved from https://bmoreart.com/2019/07/martha-...-they-age.html

[3] Phaidon Authors. (2019). Great women artists. Phaidon Press. (p. 298).

[4] Retrieved from: https://publicdelivery.org/shirin-ne...book-of-kings/

[5] Retrieved from https://archive.nytimes.com/artsbeat...am-its-secret/

[6] Retrieved from http://www.artnet.com/artists/vija-celmins/