3.5: Design, Material Culture, and the Decorative Arts

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Seventeenth-century settlers from the British Isles brought with them chests and needlework patterns, tools, and velvet cloth. They also brought ideas about how to live. They equipped their houses with furnishings that appealed to the eye. The objects that have survived- furniture, textiles, and silver- suggest a preference for intricate patterns, rich textures, and bold contrasts.

The Seventeenth-Century Interior

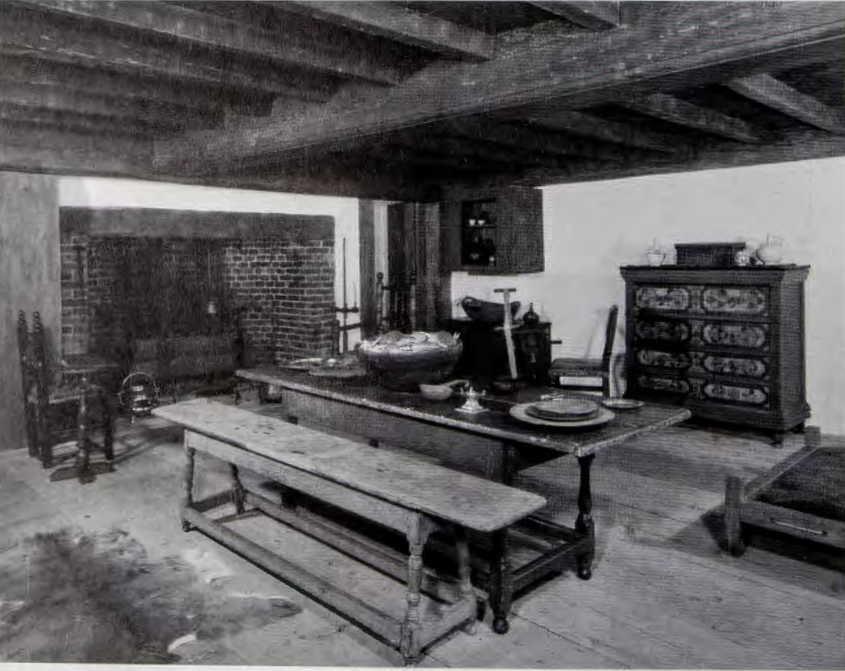

Figure 3.31 shows a group of surviving seventeenth century objects assembled in a seventeenth-century room installed in a twentieth-century museum. The low ceiling (with heavy beams and joists), the bare, wide floorboards, and the combination of furnishings for eating, sleeping, working, and storage are typical of the period. The cavernous fireplace surmounted by a massive girt ( or structural beam) is characteristic of the hall, the room where most cooking was done and where the household gathered for meals, work, and prayer. Two centuries later the idea of the kitchen/ hall with its dramatic hearth was seized upon by historically minded architects looking for symbols of American authenticity. Family rooms today are frequently equipped with fireplaces-not as shrines to outmoded cooking and heating technology, but to suggest the aura of wholesome virtue and community that the wood-burning fireplace has come to symbolize in our culture.

TWO SCHOOLS OF THOUGHT exist about the way historical buildings-whether private homes or house museums open to the public-should be treated. The first, dominant in the early and mid-twentieth century, privileges the original structure, removes all subsequent additions and modifications, and recreates "accurate" (but brand new) parts in order to simulate the original. The second, more recent school of thought believes that every era in the life of an historic structure plays a significant role in its story. Thus architectural adaptations tell critical stories about evolving attitudes, shifting technology, and economic vicissitudes. They are left intact as much as is reasonable.

THE CHAIR. In furnishing their seventeenth-century hall, the curators of the Winterthur Museum have included one armchair, two side chairs, and a long bench, suggesting what we know from other sources, such as probate inventories: that the armchair was available only to the head of the household. Side chairs ( called back stools) were sometimes available to other senior members of the household, but most ate and worked on benches and stools. Young children stood to eat, a signal of their deference and dependence. The term "chairman" derives from this seating arrangement. Some of these magisterial seventeenth century armchairs have survived, including the Pierson chair at Yale, official seat of the college's president (fig. 3.32). Even softened by feathered pillows, which would have made it more comfortable, the Pierson chair is uncompromisingly upright.

THE COURT CUPBOARD. Similarly foursquare and crafted of sturdy oak, the furniture form known as the court cupboard speaks a language of geometric solidity, but with surface elaboration (fig. 3.33). Like the John Ward House (see fig. 3.29) (the sort of prosperous home in which such an object would be found), this court cupboard sports giddy overhangs, emphasized by pendant drops. The flat top, the shelf lying on stretchers at ankle height, and the canted corners on the middle section provided places to display pewter, ceramic, and silver objects. More important, the volume enclosed in the middle section served as lockable storage for these and other valuables. Locks are one of the most telling design features of case furniture chests, boxes, desks, and chests of drawers-made in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century colonies. The introduction of locks in case furniture goes hand in hand with the new importance attached to privacy and personal property during this period. Whether imported or made locally, crafted objects were prized (and coveted) for their workmanship, their design, and, in the case of silver, gold, and textiles, their materials.

A SILVER SUGARBOX. Of all the New World crops that variously contributed to the seventeenth-century global economy (tobacco), increased human longevity (potatoes), and spurred radically new agricultural practices on every continent (corn), the only one that was memorialized with an important art form is sugar. Using silver mined by Native peoples of the western parts of Mexico, minted into doubloons in Mexico City, and often commandeered off treasure ships bound for Madrid by enterprising colonial privateers, the silversmiths of Boston, New York, and other colonial towns crafted objects of use and visual pleasure (fig. 3.34). As large as a football, the sugar box made of Mexican doubloons by Boston silversmith Edward Winslow, to keep and transport precious table sugar grown (as sugar cane) and refined in the Caribbean, uses the vocabulary of European aristocratic forms to lend dignity to his New England patron's table. The natural world is represented on the surface of this intricately wrought object by dense patterns and highly stylized foliage , in this case acanthus leaves around the top and rising from the feet. On the hasp, Saint George, the patron saint of England, gallops, sword-aloft, in quest of dragons. This sugar box is a cross-cultural object representing the travel of materials, people, and design ideas all over the Atlantic. Like the shimmering silver buttons on John Freake's coat (see fig. 3-13), such objects glittered and made resplendent the dark interiors in which they played the part of moneymade-useful-and-beautiful. Because silver was a currency as well as a craft material, silversmiths functioned as both bankers and artisans for their clients. Their crafted objects are among the most important works of art surviving from the seventeenth century. Today we tend to esteem easel painting over other art forms, but in the seventeenth century-as itemized inventories make clear-this sugar box (like· the court cupboard discussed above) would have been much more highly valued than John Freake's portrait.

We know that this sugar box- one of a half dozen surviving examples from the decade around 1700 in New England- was made by Edward Winslow because American silver was customarily stamped with the mark of its maker. The maker's stamp served as guarantee of quality in a product in which adulteration with lesser metals was not easily detectable. By contrast, no warranty was necessary for paintings, so they are unsigned. This is not because the silversmith was proud of his work while the painter was not; it is because silver objects were valued by weight. The maker's stamp guaranteed that the alloy was as reliable as the craftsman's name.

Textiles

Textiles, including objects of clothing and bedding, were among the most value~ household possessions; but most, due to their fragility, have disappeared. Before the Industrial Revolution reduced the cost of cloth and clothing, a person's dress indicated his or her social position. One's clothes were part of one's social identity and expressed one's authority and station in life. Seventeenth-century clothing transformed the body into a carefully crafted social document; a person's status was rendered legible through art and costume.

EMBROIDERY. Women in England had produced fine needlework since the Middle Ages. Beginning in the sixteenth century, they were aided in this art by the publication of many pattern books of stitches. The women who settled eastern North America in the seventeenth century brought these needlecraft skills with them, as well as the steel needles that made such work possible. One rare American example of a popular English object is an embroidered cabinet (fig. 3.35). This small chest, with embroidered panels inset on every exterior surface, is said to have been made by one or more of the daughters of Governor John Leverett of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, probably in the 1670s. The wooden box itself may have been sold in kit form, leaving the embroiderers to choose the imagery to stitch on the fabric panels. The workmanship exemplifies the artistic accomplishments of cosmopolitan young women who, born in Massachusetts, traveled to England while their father represented the colony at court. They brought back to the New World the latest in artistic fashions, and may even have started to embroider their cabinet on the long sea voyage home. The large panels on the doors depict the Old Testament theme of the presentation of Esther to Xerxes, the Persian king whom Esther persuaded to spare the lives of the Jews in his kingdom. The scene of a sailing vessel and a rowboat on the sloping front panel probably alludes to the Leveretts' transatlantic travel.

More common in this era is the sampler, a literal "sampling" of stitches that shows off the technical virtuosity of a young embroiderer. The first American samplers closely followed their English prototypes: long, narrow strips of linen in which many different stitches and patterns were worked in bands across the cloth, usually including the name of the maker, the date, and a Bible verse or moral admonitions. Designs on seventeenth-century textiles, furniture, and silver exhibit a tendency toward serial patterns, abundant decorative motifs, and abstracted floral forms. Mary Holingworth's sampler (fig. 3.36), with its geometric designs and linear outlines, exhibits this preference for nature transformed by civilization. The sampler suggests one reason why the Puritans did not commission landscape paintings. For them, nature was good only in proportion to its regularization by art, craft, and ingenuity.

A NATIVE BASKET. Very few examples remain of seventeenth-century Native American arts from the eastern seaboard. This is partly because many of the materials used in Native art were ephemeral, and partly because Native-and later, African-labor was largely subsumed within European goods and economies. Their work became invisible. Examples of seventeenth-century objects made outside the English community but preserved within it are rare. A small basket made in 1676 in Rhode Island by an Algonkian woman uses traditional upright form and weaving techniques (fig. 3.37). But woven in with the tree bark and grasses are threads of red and blue wool, unraveled from a trade blanket and introduced here to produce a work of startling chromatic and ethnic interweaving. Baskets are fragile , even when their design and execution exhibit considerable expertise. The survival and documentation of this small object evidence the high value placed on it by the Englishwoman to whom it was given, and a sense of historical obligation toward it on the part of her descendants. The integration of Native with English materials, as well as the basket's movement from one people to another and its deliberate preservation, testify to its hybrid quality and its unusual status as art within an English community.

The Carver's Art: Colonial New England Gravestones

Puritan gravestones represent colonial America's earliest tradition of surviving figural sculpture. The first grave markers may have been simple wooden posts, followed by upright slate stones incised with simple names and dates. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, a distinctive style begins to appear in the carvings on New England gravestones: allegorical and emblematic figures exhort the beholder-and perhaps the deceased-to focus on the hereafter. Over time, this style spread south into other colonies.

"THE CHARLESTOWN STONECUTTER." Foremost among the carvings of the late seventeenth century is the gravestone of Joseph Tapping. The creator of the Tapping gravestone did not leave a mark or signature. He is known today simply as "the Charlestown Stonecutter," and is believed to be the first master gravestone carver in the Boston area (p. 56).

Tapping's 1678 monument, with its profusion of English iconography, is an allegory of Puritan beliefs about death. The design comes directly from a popular English emblem book published in 1638 by Francis Quarles. The skeleton at the bottom seeks to snuff out the candle of life, while Father Time, holding an hourglass in his left hand, restrains him. These personifications of death and time derive from earlier medieval sources. Emblems such as the skull, arrow, portals, hourglass, and winged head occur repeatedly on later eighteenth-century gravestones. Most common were stones with a winged skull or cherub's head at the top, and various ornamental scenes framing the epitaph.

Like the Puritan sermons and literature of the day, such imagery admonished the pious and sinners alike to consider their souls. On the Day of Judgment, the righteous would join God in heaven; all others would burn in eternal damnation. The common Latin phrase memento mori (be mindful of death) cautioned against wasting time with vanities, for only the righteous would face the Last Judgment with God's grace.

THE LAMSON FAMILY CARVERS. In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, at least thirteen stonecutters were producing gravestones in greater Boston, some learning their craft in family workshops. Carvers earned high wages, and many became prosperous, filling commissions outside their local territories. In Charlestown, Massachusetts, Joseph Lamson, one of the most skillful early carvers, had two sons, Nathaniel and Caleb, who apprenticed in his workshop. Nathaniel Lamson carved fine gravestones while still in his teens (fig. 3.38). In Jonathan Pierpont's grave marker, 1709, Nathaniel expertly uses the iconographic formula set down by his father. A winged skull fills the curved section at the top. Below this, on either side of an hourglass representing the sands of time as they run out, small figures (sometimes called "death imps") carry shrouds. Small plaques-like miniature gravestones themselves-are inscribed with Latin phrases familiar to the pious: memento mori and fugit hora (the hours are fleeting).

On the side panels, the carver demonstrates his virtuosity. Here, the rounded tops, or finials, contain frontal portraits of males with prayer books- probably stylized representations of Pierpont, who was a minister. The Lamson carvers were innovative in this use of portraiture on gravestones. Beneath are flowers, rosettes, scrolls, and leaves-an ornamental vocabulary shared with seventeenth century furniture and needlework, as we have seen. Such ornaments became popular in sixteenth-century England, when German and Flemish woodworkers emigrated from the Continent and subsequently influenced furniture design.

The central panel of the headstone was reserved for information about the person being memorialized. On the Pierpont stone, it focuses on the life and work of minister Jonathan Pierpont. Other stones often contained cautionary phrases: Dear Friends, for me pray do Not Weep I I Am Not Dead but here do Sleep / And here In Deed I Mu.st Remain/ til Christ Shall Rais [sic] Me Up Again.