3.4: Architecture and Memory

- Page ID

- 231692

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Newcomers to the New World tended to be confident about their ideas concerning property, religion, land use, and settlement patterns. They were equally confident about architectural design, building materials, and construction methods. They knew how a church, a house, or a barn should look, and they knew how to build it. We all carry ideas about form and use in our heads: both how a structure looks and how it should be experienced. The room in which you are reading this text probably has straight walls that meet each other and the floor and ceiling at right angles; the doorways are rectangles. Although this geometry appears "natural," it is, in fact, cultural-that is, it is taught. Geometry does cultural work for us, reassuring us about rationality and giving our world predictability. It also connects us to the European building traditions imported to the New World in the seventeenth century.

The Spanish in the Southeast: Saint Augustine

The Florida town of Saint Augustine is the oldest continuously occupied European settlement in the United States. It also has the distinction of being the first Catholic mission in North America. In 1565, "La Florida," as Saint Augustine was known, was settled by some eight hundred Spa.rush soldiers and colonists on the site of a Timucua Indian village. (It would be another forty years before English settlers would successfully colonize the mainland at Jamestown, Virginia.) Through a system of involuntary servitude, local natives provided much of the food, animal hides, and labor that the Spanish needed. Like the other towns of New Spain, Saint Augustine was a gridded, planned community.

For two centuries, Saint Augustine may have been the most multiracial colony in the history of New World settlement. It brought together Spaniards born in Europe and in the New World, farmers from Germany and the Canary Islands, imported to increase agricultural production, local Native people, Africans imported as slaves, and mestizo, or mixed-blood, peoples. The material remains of this rich fusion of cultures were largely destroyed, first by an Indian uprising in 1577, then by the sacking and burning of this Spanish outpost by the English adventurer Sir Francis Drake a decade later. However, recent archaeological work has revealed that Saint Augustine households used rough clay olive jars and finely painted Majolica pottery, both imported from Spain, as well as Indian pottery made by local people and by Indians farther up the coast.

The need for a strong military defense remained paramount throughout Spain's empire. In both North and South America, the Spanish built steep-sided stone fortresses in coastal cities that were vulnerable to pirate raids. From Havana, Cuba, to Veracruz, Mexico, and from Cartagena, Colombia, to Saint Augustine, Florida, fortress architecture was a key feature of Spanish settlement. These impressive structures, based on European military design, were built largely by African and Native American labor. Thomas Smith's Self-Portrait (see fig. 3.16) includes a four-sided fortress in the background similar to the ones that played a prominent role in the colonial wars of the seventeenth century (see fig. 3.9).

CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS, IN SAINT AUGUSTINE. The northernmost point of the Spanish chain of fortifications is the Castillo de San Marcos, built during the last quarter of the seventeenth century in Saint Augustine (fig. 3.23). It replaced an earlier wooden fortress, which, after being beset by Indian attacks, marauding pirates, and pillaging Englishmen, finally proved inadequate. The castillo was based on Renaissance designs-a square with four bastions, one at each corner, surrounded by a moat-and built in a local stone called coquina. A porous mixture of shells and sand compressed by ancient glaciation, coquina was easy to quarry and shape. A Spanish military engineer oversaw the construction, employing slaves, convicts, skilled masons and artisans, and a large paid labor force of local Indians. The Indian laborers added significantly to the population of the colony, and spurred the development of new neighborhoods in Saint Augustine. With battered walls (sloping from the ground) 12 feet thick at the base to deflect cannon fire, the castillo represented a dramatic extension of the Spanish garrison plan and was among the most ambitious New World building projects of the seventeenth century.

Building in New England and Virginia

The English Americans who settled the eastern seaboard colonies and moved inland along major rivers in the seventeenth century also carried their culture with them. They did so in two ways: physically, in the things they owned lace and cattle, chests of drawers and sacks of grass seeds, Bibles and steel weapons- and mentally in the concepts they retained- field patterns, barn designs, artisanal secrets, and house plans. These objects and cognitive models were informed by ideas about design; they incorporated abstract principles and artistic practices that the colonists understood to be good, right, and practical.

Most seventeenth-century English Americans did not own paintings, nor could they find them in public places. Art museums were yet to be invented, and portraits were private family matters. But other forms of art-the grave markers that clustered in the churchyard, the straight rows in which crops were grown, and the built fabric of the settlement itself, with its town plan, fences, and architecture-these were art forms visible to and appreciated by all. We can know what these early immigrants thought by studying surviving buildings and contemporary descriptions, but also by examining old contracts, probate inventories, and town ordinances, and by conducting archaeological excavations. For the most part, colonists from the British Isles sought to replicate what they remembered from "home" - Protestantism ( except in Maryland), comfortable family-based economic units, private ownership of productive resources such as land, and so forth. They also had occasion, in a few instances, to redesign familiar architectural forms afresh. The encounter between ideas of design imported as memory and new social and physical conditions resulted in structures that would have been recognizable to their countrymen back home, but that were also somewhat different. In the New World, wood and land were plentiful whereas labor was scarce, making wood roof shingles more practical than English thatch-a cheap material but very labor intensive to install. There were also environmental differences-the temperature range from about o to about 100 degrees Fahrenheit in New England, for instance, was greater than in northern Europe, increasing the potential for damage when construction materials expanded and contracted differentially, so lapped horizontal wood sheathing called clapboarding was routinely applied to building surfaces. This technology, which accommodates wide variations in temperature and humidity, was rare in the British Isles, where wood was scarce.

HINGHAM MEETING HOUSE, MASSACHUSETTS. The Puritans, who, in early-seventeenth-century England, had maintained a low profile as an embattled minority, were a majority in Massachusetts and ready to express themselves architecturally with an innovative building type, the meeting house. Meeting houses, unlike traditional churches, were designed as social and civic spaces as well as houses of worship. The Puritans felt that God could be experienced in any setting and that religion was best expressed without the ornate symbolism of traditional churches, with their steeples, crosses, and processional spaces. The meeting house dominated the settlement. New Haven's Meeting House, as we have seen, was placed at the center of the town, and was the largest structure in view (see fig. 3.6).

The one seventeenth-century meeting house that has survived is the Hingham Meeting House, just south of Boston (fig. 3.24). This Puritan place of worship was built of wood with clapboard siding. As originally built, it eschewed a steeple (added in the eighteenth century) and other signs of special usage, and did its best to look ordinary like a rather large square house. This plain look was echoed in the choice of vessels from which Puritans and their descendants, New England's Congregationalists, took Communion: the same cups and tankards that they used every day at home (see fig. 4.23). While choosing an "ordinary" look for the shape of their meeting houses, they nevertheless expressed their exuberance for color in the painting of both the interior and the exterior. Recent scholarship suggests that the color scheme for the Hingham Meeting House included yellow, blue, green, red, orange, gray, white, and pink.1

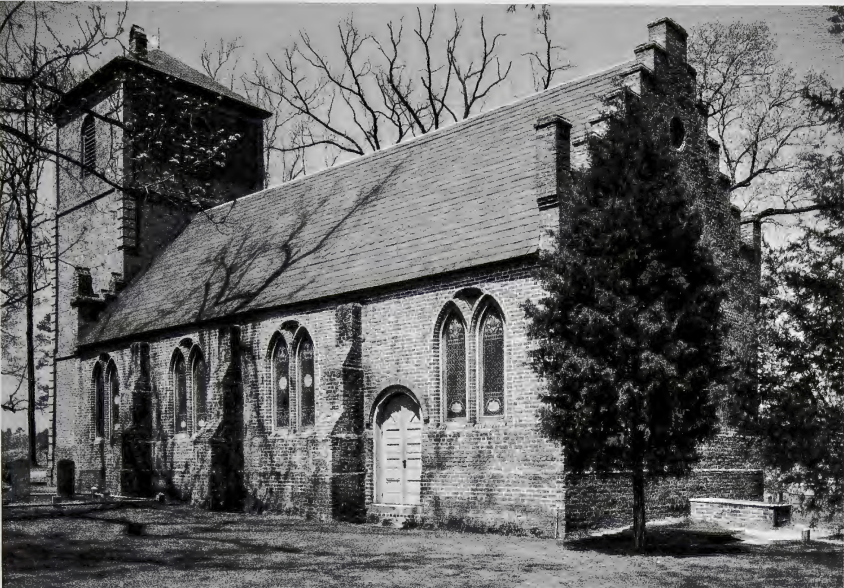

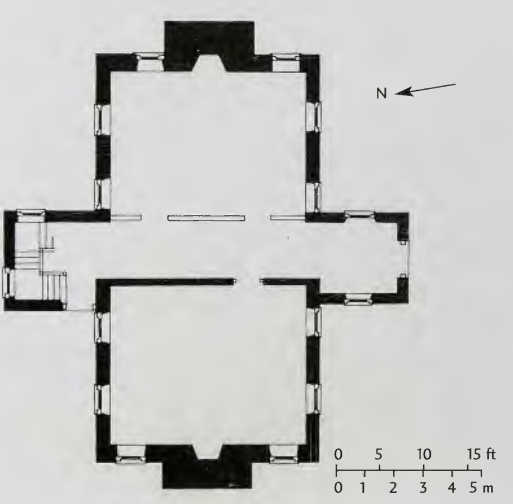

SAINT LUKE'S CHURCH, SMITHFIELD, VIRGINIA. By contrast, in Virginia the Church of England was the established church, and its buildings (and Communion vessels) followed age-old patterns. In fact, the seventeenth-century Saint Luke's Church, in Smithfield, Isle of Wight County, with its buttressed brick walls, square bell tower, and processional west entrance leading toward a great Gothic-style east window and altar table, could be mistaken for one of the small medieval churches seen throughout England (figs. 3.25 and 3.26). In terms of plan and overall form, the religious architecture of Virginia was not only more "European," it was also more similar to contemporary Spanish churches beginning to rise on the other side of the continent, than to those of their countrymen in New England to the north. New England Puritans refused the ritualized sense of space of both the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church. Their meeting houses lacked the processional spaces of most European churches.

HOUSES. Most European-Americans spent their days and nights in modest one- or two-room houses, which served simultaneously as home for possibly four to ten people, workshop, and storehouse for artisan, merchant, and farm family alike. But unlike the tiny cottages with shared party walls clustered in tightly knit villages, which the colonists remembered from England, even the humblest home in the New World sat on its own plot of land- a new way of defining home and community that still affects the way Americans think about land and resources today.

The Log Cabin

MODEST AS MOST EARLY COLONIAL HOUSES WERE, they were not log cabins, as people sometimes assume. Consistent with their cultural preference for geometric forms, seventeenth-century Anglo-Americans transformed the cylindrical trees of the forest into squared-off timbers and rectilinear planks by pit-sawing, splitting, milling, and other processes before using them to build. They transformed the clay of the riverbank into uniform-sized, fire-baked bricks to use in foundations, chimneys, and, occasionally, the structural walls of particularly important buildings.

The log cabin in North America arrived in the mid seventeenth century, introduced into the mid-Atlantic colonies (such as Delaware and Pennsylvania) by immigrants from Sweden, where such structures had a long history. In Sweden, the abundance of timber, remoteness from sawmills, and shortage of specialized builders encouraged the development of this round-log style of construction. Adopted in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century by immigrants passing through Pennsylvania en route west, the log cabin proved a useful building type on the ever westering frontier, where these same conditions prevailed. Similarly, defensive garrison houses-built of piled-up, squared-off heavy timbers (rather than frame-and-fill construction)-were sometimes built in areas where rival European populations lived in proximity, such as coastal Maine, where French-English hostilities periodically erupted.

BACON'S CASTLE, SURRY COUNTY, VIRGINIA. Few of the common one- or two-room houses survive from the seventeenth century ( except where they have been later incorporated within larger structures), but dozens of the grander four- or even six-room homes that were built for ministers, merchants, and owners of large landholdings can still be found. One relatively grand colonial home still visible today is a four-room brick house with cross gables and dramatic "Flemish" end gables known as Bacon's Castle, in Surry County, Virginia (figs. 3.27 and 3.28), which was built c. 1655. Its windows have been altered, but it retains both its exterior footprint and interior plan-two rooms to a floor, flanking a cross passage linking an imposing entry porch and an equally prominent stair tower. Although the idioms of Bacon's Castle are specific to Virginia, the emphatic chimneys, steep gables, and two-rooms-to-a-floor plan are common to surviving homes of this size throughout the English colonies.

WARD HOUSE, SALEM, MASSACHUSETTS. The largest number of surviving seventeenth-century houses is to be found in Massachusetts. Characteristic is the John Ward House of Salem, Massachusetts, begun in 1684 (fig. 3.29 ). Like Bacon's Castle, it has steep gables and a decorative chimney, echoing the basic late-medieval English architectural vocabulary. Dramatic cross gables (triangular wall sections placed at 90-degree angles to the roof), the deep shadow of a second-story overhang, or "jutt," small diamond-paned casement windows, and an envelope of overlapping clapboards are characteristic of New England houses. As in Virginia, the house has its two principal rooms on the ground floor (here divided by a behemoth chimney stack rather than a cross passage) with two chambers above, and dormer-lit garrets tucked under the roof. The groundfloor rooms in seventeenth-century houses were identified as a "hall" and a "parlor." In the former, inventories locate cooking equipment, drinking vessels, dairying equipment, and sometimes bedding; in the parlor, inventories list the highest-value bed, the most expensive furniture, and the finest eating equipment. The hall served as a combination eat-in kitchen, multipurpose workroom, and, in smaller homes, also a bedroom, while the parlor was what we would call the master bedroom, but also an entertaining space. Chambers (rooms above the hall and parlor) usually contained bedding, but they also frequently contained textile processing equipment, such as a spinning wheel, along with wool and yarn. Inventories indicate that the unheated garrets contained more bedding, but these spaces were also used for the storage of grain and other foodstuffs. In other words, almost every room was used for both sleeping and working.

A house the size of the Ward House, while unexceptional today, indicated wealth and social position in seventeenth-century North America, even though it might house seven or eight people, including a multi-generational family, apprentices, and indentured servants. Average houses consisted of one room (18 by 18 feet) with a chamber or half-story dormer room above. Large homes, such as the Ward House, built by New England communities for their ministers or by wealthy merchants to house themselves and their businesses, were often 38 by 20 feet and consisted of two full stories totaling four rooms, plus a garret. The lack of privacy, in which all sleeping chambers and most beds were shared and work was done in equally tight quarters, apparently did not cause major problems among the disparate class, age, and gender cohorts, governed by well understood systems of authority and deference. When more money became available, homeowners invested in land, livestock, and luxury goods rather than in additional living space.

FAIRBANKS HOUSE, DEDHAM, MASSACHUSETTS. Perhaps the most remarkable architectural survivor from seventeenth-century Massachusetts is the Fairbanks House, in Dedham (a town originally named Contentment). Built in the early seventeenth century by Jonathan Fayerbanke, a wool merchant from Yorkshire, it still remains in the Fairbanks family today (fig. 3.30). Fayerbanke emigrated to America at the age of forty in 1633 with his wife, Grace, and six children. He hired a master builder to construct the central four-room-plus-garret house in 1636-37. Soon after, he added an unheated lean-to (a fireplaceless back room with a shed roof reaching almost to the ground), and by 1654 the house was extended on both ends by a pair of houselets (each one room plus dormer room above) for two grown married sons. The Fairbanks family was near the top of the social scale. The house was assessed at £28 in 1648, when it was the eighth-highest in Dedham; but three years later.Jonathan's son Jonas was prosecuted under local sumptuary laws and fined for "wearing great boots" before he was worth £200. Puritan New England patriarchs kept a close eye on their families, and the town elders kept a close eye on the patriarchs. Studying town plans such as that of New Haven and house plans such as the Fairbanks house helps us understand how this was done.

Reading Architectural Plans

ARCHITECTURAL PLANS and elevations are line drawings used to describe architectural form. They provide accurate to-scale visualizations of certain aspects of buildings, such as the thickness of walls and the relationship of elements within a structure. They communicate information that the architect wants the builder to know, and that the architectural historian wants his or her readers to understand. Architectural plans and elevations follow conventions that are very useful to learn. A "plan" is a horizontal slice (or section) as seen from above. It describes the "footprint" of a structure - that is, the pattern its external walls make on the ground and the arrangement of interior walls. An "elevation" is an exterior side view of a structure. Sectional elevations can reveal interior relationships that may be invisible in ordinary elevations. They describe materials and measure the relationships of walls, windows, and doorways. Occasionally they also describe surface details, even furnishings. Partial drawings are called "details."

With its lean-to behind and its gambrel-roofed additions to either side, the Fairbanks House grew, as most such late medieval houses grew, by expanding outwardly in three directions in response to social needs. The house passed through six generations of Fairbanks owners with few changes except for the replacement of casement windows by sash windows (allowing more light into the interior). In 1832 it passed to a widow with three unmarried daughters, and later to a niece, who lived there until 1903. This unusual chain of unmarried female custodianship resulted in a delicate balance: there was apparently just enough means available· to keep the house intact but not enough to spur renovations and modernizations. By 1903 the house was regarded as a rare relic of the colonial past, and it became the focus of family, regional, and national antiquarian curiosity. Indeed, in the late nineteenth century the long sloping "cat slide" roof of this and similar early colonial structures inspired the development of one of America's most original and successful architectural movements: the Shingle Style (see Chapter 9).

STYLE AND SUBSTANCE. Seventeenth-century architecture in English North America was a product of stylistic memory (Gothic east windows, steep roofs, decorative chimneys), accommodations to local conditions (severe weather, ample wood, and the shortage of labor), and socially eloquent patterns of use (who slept or worked or ate where, in proximity to what kinds of goods and people). It was also a product of important ideas concerning the role of the master builder (trained as a craftsman, on the job, by a master builder of the previous generation), the skills of the joiner (fabricator of the individual mortise-and-tenon joints of which the building's frame was composed), and the strength of the massive wooden beams fastened into cooperative service by wooden pegs called trunnels. The engineering that gave the structure stability and shape is visible from the interiors of these structures-as we can see in the roof truss of Saint Luke's, for instance (see fig. 3.26), giving all parts of the structure, but especially ceilings, an aesthetic of muscular, functional candor.