3.1: Designing Cities, Partitioning Land, Imaging Utopia

- Page ID

- 231689

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Land planning can be an art form; a city can be a work of art. A people can express who they are by how they use the land and shape the landscape. To European eyes, the New World appeared vacant and untended. Of course, the continent had been inhabited for centuries, but Native American land use practices along the eastern seaboardseasonal migration, communal property, the delegation of farming to women-lacked the elements of improvement and private property that Europeans associated with land occupancy. In the Southwest, by contrast, the Spanish encountered Native Americans living in settlements of adobe construction, and readily recognized practices that were similar to their own. But the English, French, and Dutch on the Atlantic coast were not similarly impressed by the Eastern Woodland peoples. Although they adopted some Indian place-names for rivers and mountains and used Indian pathways (indeed, many roads in use today are paved over Indian trails), these newcomers saw the Atlantic coast as land to be "settled" and transformed into useful property.

Hispanic Patterns of Land Settlement in North America

In the American Southwest, the Spanish laid claim to whatever lands they found. They ignored Native customs of settlement, land management, and cosmological belief, imposing instead their own sense of order based on Old World patterns. As a consequence, the Spanish felt beset by hostile Indians and the threat of insurgency from colonized Natives. Along with the Catholic mission, the earliest form of Spanish settlement was the military garrison, or presidio. Likewise, the frontier agricultural village and the private plantation (or estancia) were shaped by the embattled mentality of frontier life.

Spanish colonization was fully controlled by the Crown. Authoritarian, and bureaucratically centralized, Spanish administration was driven by the need to maintain control over distant colonies, whose purpose was the acquisition of wealth and Indian conversion. In 1573, Spain's settlement policies in the New World empire were codified into 148 official ordinances, "The Laws of the Indies." (The name reflects the original error of Columbus in thinking that he had discovered a sea route to Asia rather than a new continent.) All towns in New Spain were-in theory-uniform. The Laws of the Indies dictated their size and arrangement-specifying, for example, a central, packed-earth plaza for religious processions, markets, and military exercises. Many features of Spanish colonial planning derived from the architectural theories of Renaissance Italy, and ultimately from the first-century B.C.E. Roman writer Vitruvius. These plans were intended as an ideal pattern for New World settlement. In Mexico and South America , they were imposed upon the imperial capitals of the Aztecs and the Inca.

Although the Laws of the Indies were never followed to the letter, their main features characterize most Spanish colonial towns: a grid-pattern layout of streets with a plaza at the center, flanked by government and religious buildings. The plaza functioned as an open space for social, religious, and military gatherings. In smaller towns such as Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Saint Augustine, Florida, it also served as a market (fig. 3.3). The key building was the palace of the governor appointed by the king (see fig. 2.26), a physical reminder of the Crown's authority. Social status was indicated by the proximity of one's residence to the central plaza. Accordingly, royal appointees born in Spain and the wealthier merchants lived nearest the plaza, while people of lesser status, born in the New World, were more removed. People of mixed race, including mulattos (European and African) and mestizos (European and Indian), lived on the margins of town. In Spanish colonial society, social caste was premised on purity of Spanish descent, and mapped onto the physical spaces of settlement.

EL CERRO DE CHIMAYO. In New Mexico the best preserved example of the fortified colonial plaza on a small scale (420 by 330 feet) is El Cerro de Chimayo, northeast of Santa Fe (fig. 3.4). A thriving farming village well into the mid-twentieth century, Chimayo originated in the early eighteenth century as a walled settlement that could be defended against the attacks of Apache and Pueblo Indians. The villagers' one- and two-story adobe homes were arranged around all four sides of the plaza in solid formation. Access into the plaza was at the corners, so that the village exterior presented an almost unbroken wall. Although families used the plaza itself for small garden plots, major farming was done in the outlying areas. Running through the village and connecting the inner and outer areas was an irrigation ditch, or acequia. On one side of the plaza we find a rare example of a private family chapel dating from the eighteenth century. Inward-turning in its attitude, the village of Chimayo typifies the agricultural, religious, defensive, and domestic aspects of a Hispanic frontier settlement.

British Patterns of Land Settlement in North America

Reflecting traditional concepts of community, custom, and nature, English settlements invoked the familiar patterns of the Old World while also sometimes expressing utopian aspirations for life in the New World. They were shaped by three principles: customs regarding property, farming, and patriarchy; English law regarding private land ownership; and a hopeful vision of a new civil society.

Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century settlers thought of civic space in terms of roads, houses, gristmills, sawmills, churches, and harbors; but they also thought of it as something abstract and ideal, as if seen through the eye of God. Surviving town plans show both concepts: concrete patterns of land use and abstract concepts of spatial organization.

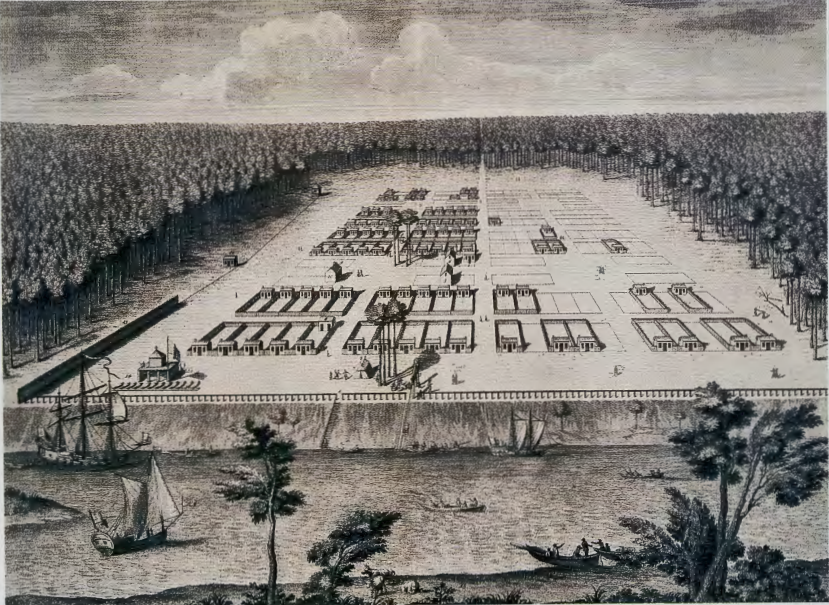

AN ENGRAVED MAP OF SAVANNAH. For example, A View of Savannah, Georgia (fig. 3.5) illustrates the colonists' defensive concerns about unfriendly natives, rival Europeans, wild beasts, and the deep forest surrounding them. The community is depicted as cleared land, extracted from the wilderness and transformed into a new civic space with roads and buildings. Savannah records a polarity between civilization-ordered, safe, and upstanding-and nature---disorganized, dangerous, and morally deficient.

With cultivation, building, and husbandry, however, nature could be made good. One of the prime instruments of this transformation was geometry. Regularity and right angles indicated the presence of civilization: straightness was not just about lines, it was a theological position. Cleared land, milled lumber, geometric rooms, upright posture, and straight roads marked space as civilized and Christian.

NEW HAVEN. The town of New Haven, Connecticut, founded in 1638 by Puritans, was laid out with an idealized geometry that equated civic space with theological and moral space. Its founders located their city where there was a good harbor and river access to inland markets. They also designed it so as to induce its inhabitants to live a godly life-to live as though they inhabited an earthly version of the New Jerusalem. Taking as their inspiration the Book of Revelation and woodcut illustrations of the New Jerusalem, the founders gave New Haven a perfectly square plan, consisting of nine squares demarcated by straight streets. The outer squares were designated as private property, to accommodate houses, shops, and orchards, while the central square served the community as a whole. On this grassy space stood the meeting house (or church). Here, too, other public functions were held; there was a burial ground, stocks for malefactors, and later, in the eighteenth century, a grammar school and a jail. The city was planned as a model for other peoples and other cities.

The Wadsworth plan of New Haven (fig. 3.6) was drawn by a Yale undergraduate in 1748 (as what we would call a senior thesis project). Wadsworth included on his map a list of the heads of households by name and occupation, leaving us a rich sociological document of this little city just over a century after its founding. More than a century after New Haven was platted (that is, surveyed) and settled, its patriarchs still arrayed themselves in a hierarchy, the most important situating themselves closest to the meeting house. By this time, however, commercial pressures had distorted the plan, causing clustered and irregular development near the harbor- the busiest segment of town- and altering its original abstract and theological unity. Such changes would continue as the city grew, but the original nine-square plan with a central green still defines the core of the city today.

ORGANIC, GRID, RADIAL Urban studies identify three essential types of city plan-organic, grid, and radial-all of which can be seen in English America. In an organic plan, streets and property lines are aligned with major topographical features. Streets follow the crests of hills and trace declivities and stream plains. They are also aligned with major human-made features such as defensive walls and wharves. Organic plans often appear to have meandering, illogical layouts. Developing from many small decisions about the use of space and access to resources over long periods of time, they are the result of accumulation, accretion, accident, and accommodation.

The second important plan type is the grid. In the West, the grid was originally used by the always-practical imperial legions of ancient Rome, who arrayed their camps in a regimental rank and file, placing the general's headquarters at the center. The Renaissance fascination with optical perspective revived the grid as a model of rationality, whereby intentionality and order could be applied to the gritty task of making a city. From the first English colonies in Virginia and Massachusetts, in the early 1600s, through the centuries of westward expansion, Anglo-American settlers took possession of the land through acts of surveying, gridding, and boundary drawing, creating in the process "a world of fields and fences," according to environmental historian William Cronon.

The third major plan type, the radial plan (fig. 3.7), derives from the Baroque period. It expresses the arrangements of power relations and social authority more directly than the other two forms. If the organic plan speaks, in general, to local and decentralized decision making, and the grid speaks to practicality and order, the radial plan speaks of the show of power, using dramatic vistas and the theatrical compression and relaxation of space to aggrandize institutions of power. The radial plan emphasizes symbols of authority and expresses a very different attitude toward space, people, and power than does the organic plan. Where the organic plan reflects a city's haphazard evolution over time, and the grid imposes a culture's sense of rationality onto the landscape, the radial plan reveals the desire of a ruling elite to display power.

BOSTON. In English America, the most common seventeenth-century plan, as seen in Boston (fig. 3.8), is organic. The principal roadways of early Boston align with or move perpendicular to major topographical features.

The Puritan Ideal

THE EARLIEST ENGLISH SETTLERS of New England were called "Puritans," a label coined and hurled at them derisively by their enemies. The label stuck; and even today, nearly four hundred years later, we tend to think of the first settlers of Massachusetts as dour killjoys. This view of Puritan society derives from the prejudices of later generations, who disparaged their Puritan progenitors as the kind of repressive folk they most loved to hate.

The "Puritan" epithet both clarifies and obscures these early English settlers for us. Members of the Church of England, they did not wish to leave the church but to purify it. Their "purifying" mission sought to rid the church of its elaborate customs and showy ritual. They wanted a simple style of worship, appropriate to what they viewed as God's truth. As their model, they took the "primitive church," Christianity in its earliest years before its institutionalization and to Puritan eyes, corruption-in Rome.

In rejecting pomp and ostentation, the Puritans were also condemning the church as an elitist institution allied with the aristocracy. They sought to make religion appropriate to the values of their own emerging middle class. The Puritans believed that salvation did not lie in a set of rituals performed by the church on behalf of the sinner but in a drama within the soul of the believer, and they called those whom God had saved "saints." They believed in a "revolution of the saints" and viewed themselves as the culmination of a biblical narrative that extended without interruption from ancient Jerusalem to their own time.

The Puritans were not democrats: like most people of their day, they subscribed to a hierarchical view of the world organized in a "Great Chain of Being," a scale that ranked all creation from the lowest orders to the highest in graduated steps, mirroring the mind of God. Though they despised the "corruption" of aristocratic culture, they nonetheless maintained the deferential customs of a class society in which the "lower orders" deferred to the authority of their "betters." They had only a limited notion of what we call today scientific causality. They viewed all events as direct signs from God, rather than as the results of natural causes.

And yet, even as they dragged a large portion of the late medieval world across the ocean with them, the Puritans also produced the first outlines of modern social life. They enjoyed the highest literacy rate in seventeenth-century Western society, insisting that salvation was tied to a person's ability to read the Bible. Within six years of founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in Boston, the Puritans established Harvard College (1636); and within ten years, they were publishing the first books in English in the New World.

Settlement bunches in merchant-dominated communities at points where one form of transportation links up with another: roads with markets, wharves with ships. Seventeenth-century Boston consisted almost entirely of private property, with the exception of the streets and a large open space known as the Common, which was public and, in contrast to the Spanish plaza, was seeded in grass for the pasturage of milk cows. Unlike horses, sheep, and steers, which could be pastured at a distance, cows needed to be kept handy for twice-daily milking. This large space was understood to be an essential public resource among the English, who were habituated to a bread-and-dairy diet. Yet while privately owned cows could fatten on the Common, the gristmills and bakeries that supplied the bread remained private businesses.

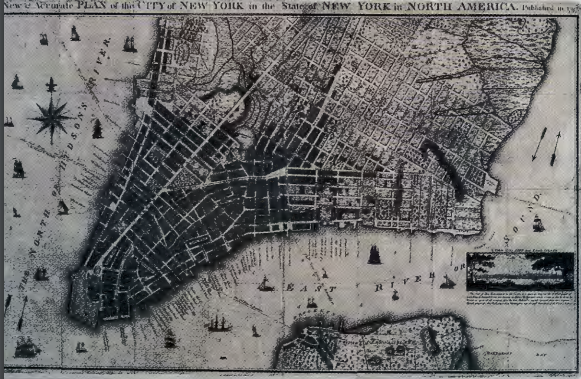

NEW YORK CITY. The Dutch in New York also developed an organic plan. A 1660 map of New Amsterdam-as it was known then- shows irregular house lots on roads that roughly parallel the two riverfronts (fig. 3.9 ). The houses, orchards, and gardens have long since disappeared, but New Yorkers "remember" Dutch settlement in names such as the Battery (where the Dutch built their fort), Canal Street (where the Dutch excavated a canal), Wall Street (just inside the defensive rampart), Broadway (the widest street in their city), and the Bowery (where Peter Stuyvesant had his farm). Still today retaining its organic street plan, the lower tip of Manhattan is distinctly different from the rest of the island.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the northern reaches of the island were increasingly laid out in a grid pattern (fig. 3.10). Elsewhere in America, too, the grid supplanted the organic plan. But the organic plan did not disappear; after the Civil War it went elsewhere. It migrated to the suburbs, where meandering roads and paths, intentionally contrived, have become associated with pleasurable, healthful habitation and class privilege.

PHILADELPHIA. To the basic question, "What tales do we tell about_ ourselves in the way we lay out cities?" the grid offers a story different from the organic plan. First, it tells a tale of separation from nature, an attitude reflected in the image of Savannah (see fig. 3.5). Second, as New Haven demonstrates, the grid embodied the ideal of a heavenly Jerusalem, perfect and planted on earth (see fig. 3.6). An important exemplar of the grid for national development is the city of Philadelphia, designed in 1682 by its proprietor, William Penn. Chastened by the Great Fire of London scarcely sixteen years earlier, Penn was intent that Philadelphia be "a green and pleasant town that never will burn." To this end, he specified the use of brick in construction, and arranged roads and utilities with a fire plan foremost in mind.

![Figure 3.11: THOMAS HOLME, A Portraiture [sic] of the City of Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania in America, 1682, from a restrike in John C. Lowber, Ordinances of the City of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: 1812). Olin Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.](https://human.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/132788/clipboard_e6b2790568b94b2ddbccc02ab212e59dd.png?revision=1)

He also incorporated geometric principles that he believed revealed the rationality of "Nature" (fig. 311).

Laid out between the Schuylkill River ( connecting Philadelphia with its hinterlands) and the Delaware River (connecting the city with the Atlantic marketplace), Philadelphia's gridded brick cityscape became an important model for the nation. Philadelphia's plan (which reflects its origins as a Quaker settlement) is rational, clear, and humane, punctuated by five public squares (four of them planted with shade trees according to the 1682 plan). The grid was, and continues to be, associated with an ideology of equal access and fair dealing. Its allowances for rapid response to fire also permit easy orientation for visitors unfamiliar with the city. Philadelphia prospered, as a port exporting the agricultural goods of America's richest farmland and as an entry point of European immigration, especially during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Immigrants stopped in Philadelphia before heading west and took with them the memory of a large-scale, highly functional urban grid. In the mid-nineteenth century, the railroads adopted the grid plan for the many towns in the Midwest and West that they established along their rights of-way. The grid became a hallmark of European-American settlement, a stamp of regularity, efficiency, and rationality on the landscape.

THE ORDINANCE OF 1785. The Ordinance of 1785 was the second of several acts passed by Congress dealing with the settlement of the Northwest Territory: the land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. It surveyed the land and partitioned it into 1-mile squares, each containing 640 acres and called a section. Thirty-six sections constituted a township, the political unit of middle America. A quarter section (160 acres) made up a standard family farm-the economic and social unit that has since been mythologized in so much American art and literature. Roads and fences followed these property lines, as one can still see from an airplane, establishing a grid in which the natural is made geometric, and the political expressed in design.

In the late eighteenth century, Napoleon Bonaparte lost whole armies on islands in the Caribbean trying to quell slave uprisings and restore sugar production. Quitting the Caribbean, he had no more use for the central portion of the North American continent which had been designated the breadbasket for these plantations. In 1803, Thomas Jefferson, then president, purchased these immense lands for the United States. The Louisiana Purchase consisted of 828,000 square miles stretching up the Mississippi River from New Orleans to the Rocky Mountains and Canada. This land, too, was divided into a patchwork of 1-mile sections.

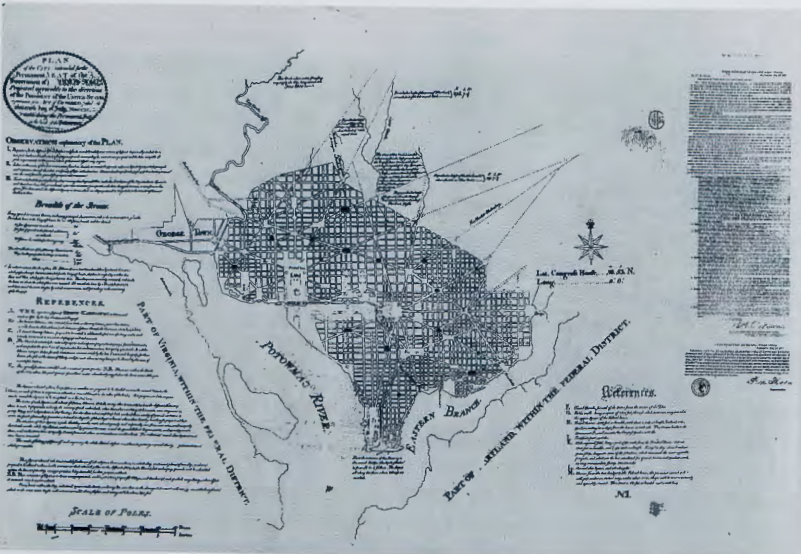

THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA. The radial plan is less common than the grid or the organic plan. Used in the early 1700s in the colonial capitals of Maryland and Virginia- Annapolis and Williamsburg-the radial plan is most grandly realized in Washington, D.C. Unlike Boston, New Haven, New York, and Philadelphia, Washington was not a colonial settlement. It was designed specifically as the capital of the new nation by a French immigrant, Pierre Charles L'Enfant. The model L'Enfant chose was the most dramatic and imperial plan available. Artist, military engineer, and the son of a court painter, L'Enfant had been born in Paris and was familiar with Versailles-the splendid Baroque palace built for Louis XIV L'Enfant came to the colonies, as did many other French sympathizers with the patriot cause, arriving in 1777. Fourteen years later, in 1791, George Washington hired him to design the new capital city and its public buildings. Although embroiled in land speculation and dismissed the following year, L'Enfant nevertheless shaped the city of Washington as it was built-a grid overlaid with a dramatic radial plan (fig. 3.12).

In his own words:

Having determined some principal points to which I wished to make the others subordinate, I made the distribution regular with every street at right angles .. . and afterwards opened some ... as avenues to and from every principal place, wishing thereby not merely to [contrast] with the general regularity but also to offer pleasant prospects and to connect principal buildings giving to them reciprocity of sight and making them thus seemingly connected.

Fifteen squares with "statues, columns, obelisks" and grand fountains were to punctuate the cityscape, according to L'Enfant's plan. Washington was conceived on such a grand scale that the city would experience a century of development before it caught up with L'Enfant's imperial plan.