3.3: Hispanic Village Arts

- Page ID

- 231691

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)New Mexico has produced a rich tradition of carved and painted religious art, which has embodied the communal and ethnic identities of Hispanic New Mexicans from the eighteenth century to the present. While preserving this tradition, however, the village arts of New Mexico have never been static. They have undergone continual revival, transformation, and adaptation in the face of changing historical circumstances. To understand this remarkable flowering of local art, we need to look at the forces shaping regional life in New Mexico, which from the sixteenth to the early nineteenth century was a colonial outpost of New Spain.

The two major colonizing powers in the New World Spain and England- were both located on the periphery of Europe. Each assimilated the Renaissance revival of classical learning and the construction of perspectival spaces somewhat later than its neighbors. In colonial New Mexico, traditional habits of thought persisted alongside a pre-modern material culture. Anonymous carvers on this colonial frontier shared with the artists of seventeenth-century New England an emphasis on two-dimensional forms characteristic of pre-Renaissance art. All this had changed in New England by the end of the seventeenth century, when trade with the Atlantic world introduced the English colonies to the latest European tastes. New Mexico's isolation, however- along with local preferences- preserved these older visual forms well into the early nineteenth century.

The Santero Tradition

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, anonymous artisans known as santeros produced images of the saints (santos) for domestic and communal use. Placed in private family chapels, in village or mission churches, or in moradas-buildings dedicated to religious male confraternities-images of the saints were believed to act as intercessors on behalf of a household or village in times of need or crisis. They were (and still are) the object of daily household devotion and prayer.

SAINT JOSEPH BY RAFAEL ARAGON. At the same time, carved statues of the saints, or bu.hos, covered With gesso and painted, gave great spiritual immediacy to everyday worship in the villages of northern New Mexico. Rafael Aragón's Saint Joseph (fig. 3.17) bears the Christ child on his extended arm. In European painting, Saint Joseph is traditionally depicted as an aged and frail figure. In this example, however, Saint Joseph appears as a youthful Spanish patriarch. He wields his flowering staff-emblem of his role as the Christ child's surrogate father-with the benevolent authority of a spiritual guide.

Retablo Painting and the Santero Tradition

Paintings of the saints initially appeared as part of an elaborate architectural frame, placed behind or above an altar, known as a retablo. The major surviving example of the retablo in New Mexico dates from the early nineteenth century. It is located in the Church of San José, in Laguna Pueblo, which we have already examined as a fusion of Native and European forms (see Chapter 2). We now return to this church to consider the contribution of Hispanic, rather than Native, artisans.

RETABLO AT SAN JOSÉ, LAGUNA PUEBLO. Dating from between 1800 and 1809, the retablo at the end of the nave is the work of an anonymous itinerant artist known simply as the Laguna Santero, who was active in New Mexico from the 1780s until around 1810. Like many altarpieces, this one has been retouched. At the center of the San José retablo is Saint Joseph, holding the Christ child. The tier above contains a representation of the Trinity (fig. 3.18): three identical figures carrying different attributes (scepter, dove, and lamb). This way of representing the Trinity may be traced to the medieval period, but had mostly fallen out of use by the Renaissance, as European Catholicism came to favor three distinct representations for the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The older image of the "Triune" Trinity (three in one) persisted, however, on the New Mexico frontier, a striking instance of a vernacular tradition with roots in the pre-modern past.

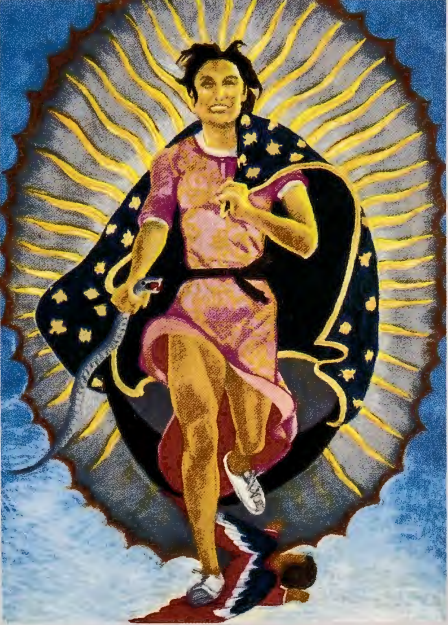

KNOWN AS THE "MOTHER OF THE AMERICAS," Our Lady of Guadalupe (fig. 3.19) is the patron saint of Hispanic Catholics throughout Mexico and the United States. Reaching across national borders, she has evolved into a symbol of Mex.ican identity and an image connecting Mexican Americans throughout th~ Southwest. According to legend, a vision of the Virgin appeared before Juan Diego, an Indian peasant, outside Mexico City in 1531. Crowned with stars, surrounded by dagger-shaped points of light, her feet resting on a crescent-shaped moon, the dark-skinned Virgin of Guadalupe is a New World version of the much older European Virgin Immaculate, while also drawing upon objects of pre-Hispanic worship such as the Aztec earth goddess.

The meaning of Our Lady of Guadalupe has changed over time and according to context. Her popularity was initially a useful means of spreading Christianity among indigenous Mexicans (she spoke to Juan Diego in his native Nahuatl language). In the early nineteenth century, in the years surrounding the Mexican Revolution, she became a source for a distinct New World identity that focused on aspirations for independence from Spain. In the twentieth century, she developed into a symbol of ethnic pride that promoted solidarity during times of political and social struggle, guiding striking farm workers in California as well as offering protection to Hispanic communities across the Southwest. Mexican-American grocers have her image painted on storefronts; she adorns calendars, cars, earrings, and T-shirts, transcending religious affiliation. For feminist artists, she has come to embody the spirit of liberation.

Yolanda Lopez's Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1978, transforms the Virgin into a figure of independence and self-assertion (fig. 3.20). With her running shoes, frontal pose, and tight grasp of the snake in her hand (the snake is both a Nahuatl god and a Freudian symbol), Lopez's Virgin leaps out of the picture frame and into the future. Rather than rejecting the past, she appears to carry it along with her. Each generation of Mexican Americans appropriates the Virgin of Guadalupe anew, adapting her image to meet the needs of particular communities and affirming their ties to the mother culture of Mexico.

SANTERO PAINTING. Throughout the nineteenth century, the work of the Laguna Santero and other masters was extended and then modified by followers. Santero design became simplified and flattened, moving away from the illusionism of the eighteenth century to produce a quasi-abstract appearance.

Working on pine panels with water-based paints similar to those employed by the Pueblo Indians, New Mexican santeros reconceived three dimensional volume in linear terms. Forms were outlined in black, and colors were rarely shaded; draperies were rendered as a series of flattened patterns with minimal descriptive function (fig. 3.21). The key to this stylistic transformation lies in the international circulation of printed matter. Santero painters relied on religious engravings of Mexican Baroque and Rococo art, which translated rich painterly effects into line. Tonal variation in prints was translated by both santeros and later provincial New England artists into flat blocks of color. New Mexican artisans transformed the swirling draperies, dramatic light effects, and immediacy of expression that characterized Baroque art in Europe and Mexico City into increasingly abstract, simplified, and immobile images of saints floating in non-perspectival space. Their simplified forms reflect the linear shapes of illustrated books and prints.

NATIVE ELEMENTS IN SANTERO PAINTING. Some of these religious images are believed to be the work of Native American artisans.

A painting from the early nineteenth century by an artist known only as the Quill Pen Santero, Saint Peter Nolasco (fig. 3.22), shows the Spanish saint ascending into heaven. The borders of the image are filled with clouds, but they are not the usual clouds of European art. Instead they are the Pueblo Indian symbol for clouds. Framing the saint's skyward ascent, these repeated Pueblo symbols suggest how profoundly Catholic and Native traditions intermingled in the region's art.