3.6: Representing Race- Black in Colonial America

- Page ID

- 231694

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Visitors today to the British Museum, in London, may discover an odd fact. A seventeenth-century drum housed in the museum's collections is not what it appears to be (fig. 3.39). The drum displays all the signs of West African craftsmanship. The indented base, cylindrical body, pegged membrane, and decorative carving resemble drums made by the Asante peoples of Ghana. A glance at the museum label, however, reveals that the drum does not come from Africa but from colonial Virginia. It was collected by British agents in the New World and then acquired by the London physician Sir Hans Sloane in 1645. Sloane's acquisitions form the nucleus of what would subsequently become the British Museum.

Labeled simply "Slave Drum," this object tells a remarkable story. It suggests how African cultures survived far beyond the boundaries of that continent. Made from West African wood, it must have been brought to North America, perhaps by its maker, a woodcarver captured in Africa, who was shipped across the Atlantic and enslaved in Virginia. A woodcarver enjoyed elevated social status in many West African cultures, and probably possessed such status among fellow slaves. The drum was used for dance, rituals, and musical talking: with its deerskin head, it reproduces the rhythms and tones of Asante speech. Many European colonists feared African drumming, interpreting the music as a call to rebellion, and sought to ban it.

To a black audience, however, drumming signified the continuity of African identity. It bound the Old World to the New, bringing familiar cultural forms into unknown situations. Objects like the Slave Drum allowed peoples abducted from their homelands to sustain practices and memories that without such artifacts they might otherwise forget. The survival of particular West and Central African customs depended on artisans who could remember the past and refashion it in America. Over time, these artisans adapted new materials-different woods and fibers-to altered ends, transforming objects of the African diaspora into African American art.

The First Africans in America

The first enslaved Africans imported to North America came by way of the West Indies and the Caribbean. In 1619, John Rolfe, a Virginia tobacco planter, noted the arrival of "20 and odd Negroes, which the Governor ... bought [in exchange] for victualles." Slavery was not unique to the New World. Arabs and Europeans had owned slaves centuries before the discovery of the Americas, and Africans enslaved other Africans from different ethnic groups. No group, however, desired to enslave members of its own religion. Arabs turned to sub-Saharan Africa for slaves who were neither Christian nor Muslim. They purchased these slaves from African tribal lords, who provided European slave traders with an abundant supply of fellow Africans, often captured in raids upon rival tribes. In Arabic, the word for slave, abd, became synonymous with 'black man."

British North America slowly adopted the slave practices of the Spanish and Portuguese. In the colonies, the English first tried to use the Indian population as a source of cheap labor. In early Carolina, settlers encouraged Indians to "make War amongst themselves," so that white planters could purchase captives enslaved by other Natives as trophies of war. The Natives, however, made poor laborers. Indian men refused to engage in agricultural labor, which they considered women's work. Because they knew the countryside better than their white captors, they readily escaped. Furthermore, the intertribal warfare that the English encouraged too often developed into Indian attacks upon white settlements.

COLONOWARE. Throughout the South, contact between African slaves and Indians was frequent and one result of this was a form of pottery called colonoware, which combined ceramic traditions of both cultures. Colonoware (named after the colonial period, when it was manufactured) is a type of handmade ceramics fired over low heat (hearths rather than kilns). This pot from the eighteenth century was found buried in the mud of the Combahee River at Bluff Plantation, South Carolina (fig. 3.40).

The decorations resemble African patterns, but they are incised onto a pot shaped in an Indian style. Colonoware was used by masters and slaves alike. Its hybrid form suggests one way that traditional artifacts acquire new meanings through cross-cultural contact.

The Descent into Race-Based Slavery in America

When African and African Caribbean slaves first arrived in English North America, they were treated by the same rules that governed indentured servants. They worked for a contractual period of four to seven years, and upon the completion of their indentures, they were granted their freedom and the right to own property. Like workers from the British Isles and continental Europe, these African laborers were viewed as members of a vast multiracial labor force.

Within a scant forty years, however, the status of African slaves changed. Labor-intensive crops like tobacco and, later, rice, together with a shortage of workers, led European planters to declare Africans "chattel." While indentured servants from Europe were free to start afresh after completing their contracts, Africans lost whatever legal rights they had possessed. They were considered, instead, to be hereditary property held in perpetuity by their owners. In 1661, the Maryland legislature declared slavery to be a lifelong status. Virginia followed suit in 1670. Over the next several decades, English North America developed the legal scaffolding necessary to support a racialized and increasingly repressive system of slavery. That system would stand for the next two hundred years.

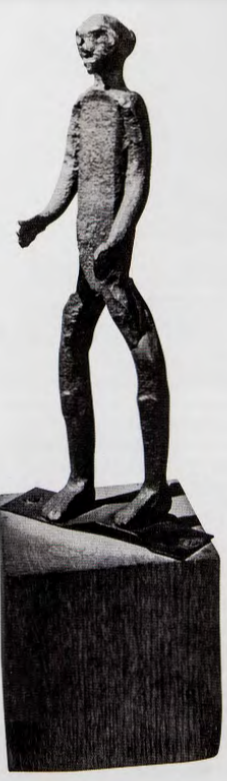

TWO AFRICAN AMERICAN SLAVE SCULPTURES. Two artifacts surviving from colonial times demonstrate the persistence of West and Central African forms and memories i.n the everyday life of American slaves. A wrought-iron figure from the late eighteenth century of a standing man with outstretched hands, flattened chest, and elongated torso was discovered in a blacksmith shop in the slave quarters on the site of a plantation in Alexandria, Virginia (fig. 3.41). The figure had been buried in the dirt floor, which suggests that it might have been hidden from sight and used for ritual purposes. It duplicates almost exactly figures produced by the Mande peoples of Mali, who were known for their blacksmithing skills.

In a parallel vein, a runaway slave in the eighteenth century carved a pine figure holding a rounded vessel (fig. 3.42). The forward thrust of the seated man's arms and thighs is balanced by the verticality of his torso and lower legs. His stability and bodily repose, when combined with his abstracted features, form a sculpture of remarkable dignity. Seated figures like this one derive from Congo (Central Africa) carving traditions.

As enslaved Africans were denied legal rights, they were also denied their heritages. Early slave traders had distinguished groups of Africans by terms like "Angolan," "Calabar," "Nago," and "Koromanti" (a term to describe first- and second-generation African-born slaves). Though imprecise, these terms acknowledged differences among the peoples of West and Central Africa. However, with the passage of time and the consolidation of slavery, most traders reverted to simpler and more racially charged terms, "Negroes" (from the Spanish word for 'black") or "blacks." This shift in terminology imposed a fiction of sameness on all slaves at the same time as it rendered the division between black and white absolute.

As recognition of the multiplicity of African cultures disappeared, so did respect for the African American's humanity, to be replaced by a pejorative notion of blackness adapted from medieval characterizations of the devil (as a black man). This attitude ignored the diversity of African peoples, languages, and customs, and lumped Africans together as a childlike, inferior, even depraved race. Thus the series of social, legal, and political steps taken to obtain and exploit cheap labor developed into a system of race-based enslavement and segregation that seemed preordained and universal. In the course of little more than a century, racism became institutionalized.