3.6: Mexican Baroque (Late 15th century - 1868)

- Page ID

- 120745

Introduction

The devastating decline of the Indigenous people still occurred throughout the seventeenth century. Governmental conflicts developed among the Spanish Crown, the clergy, and the Criollos (European descent born in the Americas). The competition among the imported Jesuits, Franciscans, and the Dominicans religious orders continued during the Spanish Crown. The Crown imposed high taxes on silver mining and invested control of the lands in the hands of natural-born Spanish citizens. The Criollos were taxed at a higher rate than Spanairds. During the eighteenth century, discontent and riots led to changes in the government and cultural behaviors.

Changes were also reflected in the arts with competition between artists. Guilds were set up in the middle of the 16th century, and although regulations did not allow Indigenous artists, many Spanish artists used them as apprentices. European artists began to travel to Mexico and Peru. As the immigrant's identity with the Viceroyalty of New Spain increased, the influence of the miraculous Virgin of Guadalupe expanded into visual art. The addition of artists born in Mexico of European and Indigenous descent changed art and the concepts of beauty. Art transformed from the lingering Renaissance styles to a unique style of Mannerism and Baroque art. A cultural identity grew from the style, blending traditional, new, and ethnic diversity.

Oversized altarpieces were created by woodworkers and craftsmen, assisted by Indigenous locals to add paintings and sculptures. Although altarpieces were found all over Europe, Spain began the tradition of large retablos late in the middle ages. In colonial Latin American, the patrons of retablos took advantage of Indigenous artists' skill of woodcarving for the altarpieces. Unfortunately, since earthquakes are common in Latin America, many of the original retablos were destroyed while other works of art have been moved or stolen.

Paintings were often completed in the European Mannerism and Baroque styles, both altered for the New World. For example, Mannerist art in Europe focused on complex subjects and visual artifice (elongated proportions of bodies). The unorthodox Mannerist style was simplified for the Indigenous people, including changing the Mannerist icy colors to the Latin American earthly colors.

Andres de Concha (1554-1612) contributed several paintings to the altarpiece of Santo Domingo Yanhuitlan; notably, the Adoration of the Shepherds (3.6.1) on the far-right lower level, a common European subject. The painting has Mannerist tendencies, with elongated figures. The Christ child is presented facing outward rather than towards the adoring Magi to make the image more easily understood. The facial view emphasized the importance of Christ and identified him as the central figure.

In South America, Italian immigrant Bernardo Bitti (1548-1610) created the central panel of The Virgen and Child (3.6.2) in the altarpiece for the Church of La Compaña, Arequipa, Peru. Mannerism style is evident in the icy blue and pink colors, the elongation of the human form, and the emphasis on hand gestures. However, the Virgin and Child are directly facing the viewer.

The next generation of artists incorporated some Mannerist tendencies with an ordinary, prosaic style to create more approachable Christian themes. Artists were impacted by famous artworks (via black and white prints) from Flanders in Europe. Traditionally, Flemish art was realistic and detailed. Flanders was under control by Spain at this time. Many ships left the port of Antwerp for the Viceroyalty of New Spain, bringing the influence of Baroque art and architecture to enhance Catholic religious ideals.

Mexican Baroque Architecture

Baroque style is often seen through elaborate ornamentation and ostentatious display of subject matter to capture the religious fervor in art. Church altarpieces become more extensive and ostentatious, as well. Additionally, architecture, and specifically cathedrals, became a representation of mixing cultural and racial beliefs as "religious edifices were the axis mundi of the community, embodying not only the hegemony and influence of the Catholic Church but also the ambiguous and complex identity of its people."[1] Although European Baroque influenced artists in Mexico, the style was transformed; more ornate, the use of specialized azulejos (tile), unique plasterwork, specific local images, and the use of Churrigueresque.

Jerónimo de Balbás

Jerónimo de Balbás (1680-1748) was born and trained in Spain, an architect, and sculptor. He designed the main altar for a cathedral in Sevilla using estipite columns. The columns are generally decorative because their construction with inverted cones, multiple sections, or curved intersections is not substantially weight-bearing. The estipite columns were used for framing and outlining facades, niches, or altars to enhance the architectural components. Balbás embellished his columns with elaborate plasterwork and tumbling angels, all examples of the ornate Churrigueresque style he brought to New Spain in 1718 and started designing the altar in the cathedral Mexico City. Though Balbás is credited with importing the Churrigueresque style, estipite columns can be seen in buildings all over Mexico, including the late 18th-century façade of Iglesia de San Diego in Guanajuato, Mexico (3.6.3). The estipite columns on either side of the door are notable for their vertical upward flaring and decorative design.

When the Spaniards arrived in Mexico, they planned to recreate their churches based on the architecture of Spain. However, the new land required new ideas, a hybridization of the beliefs and concepts of the colonizers, and the integration of views and opinions from local people. Earthquakes were prevalent in the area, and buildings had to be designed differently; outside attacks required thick, less penetrable walls, the changing hydrostatic pressure in the water table, and the local building materials were different, more colorful.

The major church in Mexico is the Catedral Metropolitana de la Asunción de la Santísima Virgen María a los Cielos (Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven) (3.6.4). The immense cathedral was started after the original Spanish conquest of the region in 1573 and was not completed until 1813. The early conquistadors destroyed the Templo Mayor of the city of Tenochtitlán to build the main square and a new church in its place. Throughout time, different sections of the cathedral, artwork, and ornamentation followed the architectural style of the era, from Gothic to Baroque to Churrigueresque. The structure also incorporated views from different master builders, architects, religious groups, government leaders, and local people as it developed into an important societal influence. The cathedral is immense, about 59 meters wide and almost 128 meters long. With the addition of the two bell towers and twenty-five bells, the cathedral stands 67 meters high.

The cathedral has five major large altars; two of the altars were designed by Jerónimo de Balbás. The massive Altar de los Reyes (Altar of the Kings) (3.6.5) forms the altar wall on the east end of the cathedral interior and soars 25 meters high. With a depth of 7.5 meters, the altar resembles the feeling of a grotto, its nickname la cueva dorada (the golden cave). The structure of the altar is based on four massive estipite. The columns have narrow, squared bottoms tapering upwards into sections with capitals and ornamentation of vines and foliage, abstract designs, and multiple cherubs. It is all carved from wood and covered with gold gilt, the ultimate in Churrigueresque style. In between are numerous niches are filled with sculptures depicting different royalty and saints in polychromed wood. The top portion displays figures of the holy family. Retablos are large paintings mounted in wooden frames on the sides; the retablos became a ubiquitous element throughout churches in Mexico. The ornate, leave no blank space style became a standard concept for other Mexican Baroque artwork.

The Altar del Perdón (Altar of Forgiveness) (3.6.6) is positioned in the central nave and the first altar seen when entering the cathedral, a stopping place for people to pray. Jerónimo de Balbás designed the second altar for the main cathedral. In Europe, stone was the primary material for columns; however, the estipite, molding, and other surfaces were covered with elaborate plasterwork using the technique yeseria of geometric patterns. Yeseria was used extensively in Spain by the Moors, who had controlled large portions of Spain for hundreds of years in the middle ages. The concepts were brought to Mexico as a significant part of the new designs.

La Capilla de Nuestra Señora del Rosario (The Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary) (3.6.7) displays the excessive ornamentation found in late colonial churches. The chapel was constructed next to the Church of Santo Domingo in Puebla as a place of worship and method to convert and educate the Indigenous population. Although Baroque in style, the chapel's interior displayed the extreme details illustrated by the polychrome plasterwork covering most of the interior of the chapel.! It has been described as "one of the most outstanding features of Latin American architecture […] an obsession with integrating the harmonious fusion of the visual arts […] with the spatial qualities of architecture."[2]

The chapel's interior (3.6.8) is swathed in carved plaster designs, gold leaf, and tiles, reflecting diverse images and ultra-Baroque.

Jose Rodiguez Carnero

Along the side walls of the nave are immense canvases (3.6.9) painted by Jose Rodiguez Carnero (1650-1725) based on themes of the Virgin Mary, memorial events in her earthly life. The somber chiaroscuro tones of the paintings are highly contrasted with the opulent, gilded plaster surrounding the images. Under the paintings, the walls are covered with a sumptuous row of gilded plaster cherubim and the coat of arms representing the Dominican order of priests. \ was based on highly repetitive patterns found in Islamic or Portuguese tile work.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Side wall paintings in chapel retablos (paintings of saints set in wood frames), CC BY-SA 4.0

Under the gilded cherubim, the façade is lined with panels of Talavera pottery azulejos (3.6.10). The style of Talavera pottery was brought from Spain to Mexico, where it was widely adopted and used for the walls of many buildings. A specific type of high-quality clay was found in Puebla, creating a significant pottery manufacturing center. Talavera pottery was glazed with a mixture including tin and lead, then colored with natural pigments to make orange, yellow, blue, black, green, or a form of mauve. The azulejos pattern.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Talavera tiles inside the chapel, CC BY-SA 4.0

Templo de San Francisco Acatepec, in Puebla, was started in 1650 and was not completed until 1760. The Franciscan order came to the region, bringing religion to the local people. The church (3.6.11) and other buildings in the area are recognizable from the unique and excessive Talavera tile facades, coupled with red brick and topped with a magnificent tower (3.6.13). The bright polychromed Talavera azulejos were designed and fashioned for the church based on the religious use of blue and white to represent the Virgin and green and yellow for Joseph. The façade of the church is enclosed with the small estipite patterned columns stacked on top of each other. At the top of the façade is an oculus with molded star-shaped cornices. In this case, the azulejery reaches delirium. And admiration for astonishment. The work is a great ceramic toy raised on earth. In front of it, one no longer thinks about whether it is a church or whether it obeys a Borrominian pattern. We are genuinely within the world of whimsical, of dreaming. Everything in it is color and brightness.[3]

The interior of the church follows the same ornate, (3.6.12) excessively embellished design as the outside façade. The interior included golden moldings, corbels, Solomonic columns (similar to Bernini's columns on the Baldacchino of St. Peter's in Rome, Italy), and cherubs. Along with polychromy, angels, figures, and faces formed the unique plaster decorations in the space around the altar. Figures of saints carved from wood and enhanced with the technique of estofado stand in the niches. The carved statue was covered with gold or silver and color painted or glazed. When the color was dried, different patterns were incised to reveal the underlayer of metallic. These techniques became a standard method to make small statues throughout the country. The work inside was performed by Indigenous workers, and some of the elements found in the ornamentation reflect native concepts. Some headdresses were Aztec in shape, (3.6.14) placement of hands resembled Indigenous art, and different native fruit was incorporated, all demonstrating the crossover of ideas.

Paintings

By the 18th century, artists were integrated into the society, and known for a large body of work, despite not being of pure Spanish origin. Artist Cristóbal de Villalpando was a Criollo and documented Spanish descendent. Juan Correa was considered a Mulato Libre, a free man descended from an African slave in the Americas, and his father identified as a mulatto physician from Spain. Artistic standards during the previous century were based on values from Spain transplanted to the new land and based on accurate drawings, brilliant palettes, or overly expressive faces. Now artists began to use a lighter, reduced palette, less expression in the faces, and simpler folds in the garments. With an assortment of backgrounds and experiences, the artists invented innovative iconographies, started different educational sites, and infused new vigor into the art of Mexico. "Attesting to their extraordinary versatility, the artists who created mural-size paintings to cover the walls of sacristies, choirs, and university halls were often the same ones who produced portraits, casta paintings, painted folding screens, and finely rendered devotional imagery."[4]

As Criollos began to develop their values independent of Spain, they developed Mexican artistic behaviors. Artists like Correa and Villalpando still maintained enough European Baroque styles and integrated Mexican ideals to satisfy and gain wealthy citizens and clergy patronage. Their large-scale paintings for the churches started the move towards the unique Mexican models.

Cristóbal de Villalpando

Cristóbal de Villalpando (1649-1714) was a Criollo born in Mexico City and whose family was well connected and influential in the new country. He became a painter when Churrigueresque architecture was evolving, embracing the new ideas instead of the Baroque of the Spanish artists. Villalpando created large luminous paintings to match the elements in the new churches. Influenced by Rubens, his dynamic compositions were often painted with similar loose brushstrokes and ornamental drapery. He incorporated local concepts with anatomical variabilities and expressive positioning of figures, one of his trademarks. Although Villalpando's work relied on standards of Sevillian painting, many areas in his paintings had idiosyncrasies based on Mexican ideas. He is noted for "leaving one of the most abundant, sensual, imaginative, and vital bodies of work produced in New Spain – but also one of the most unequal in quality, perhaps owing to that very fecundity."[5] Villalpando was also one of the first artists in Mexico to sign his work, adding he was not just the painter but also the painting was his invention.

One of Villalpando's early masterpieces included two different scenes; Moses and the Brass Serpent at the bottom and the Transfiguration of Jesus (3.6.15) at the top. The painting is a compilation of a story from the Old Testament and the New Testament, creating an immense image over 8.5 meters high made for the Cathedral of Puebla. The lower section was based on the biblical story of Moses, with his reflective horns, as he used a brass serpent to heal the Israelites. The scene was crowded with contorted people who are the victims, the dark palette reinforcing the agony. The top image depicts the change of Jesus' mortal body into light, highlighting Villalpando's mastery of luminosity. He moved the viewer from the commotion at the bottom of the painting upwards to the explosion of light at the top. His religious paintings were flamboyant with visions of agony, despair, and suffering while still imparting the potential of redemption, forgiveness, and love.

.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\): Moses and the Brazen Serpent and the Transformation of Jesus (1683 oil on canvas 865 x 550.1 cm) Public Domain

Images depicting the adoration and devotion of Mary were popular in Mexico and supported by the clergy. Villalpando painted Our Lady of Sorrows (3.6.16) with a dagger in her breast, symbolizing the pain from her sorrows. She sits statically, the angels behind her bringing movement to the painting, their wings projecting in a diagonal, upward motion. Each angel holds one of the sorrows, their faces portraying sadness. Mary wears a dark-colored gown, illuminating her prominence, the angels formed in gold and red to reflect each face's luminosity.

_04.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\): Our Lady of Sorrows (c. 1680-1689 oil on canvas 147 x 208.5 cm) CC BY-SA 4.0

In the painting, The Deluge (3.6.17), God's destruction of the world is represented. Noah's Ark floats in the background, the dark, ominous skies filled with lightning as the people are submerged in the water or furtively trying to flee the scene of death and destruction. Villalpando used the vision of the bronze-hued ark, inaccessible, the possible deliverance from earthly evils to represent Christian salvation for the sinful population.

.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): The Deluge (1689 oil on copper 59.1 x 90 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\): Adam and Eve in Paradise (ca. 1689 oil on copper 60 x 87.9 cm) Public Domain

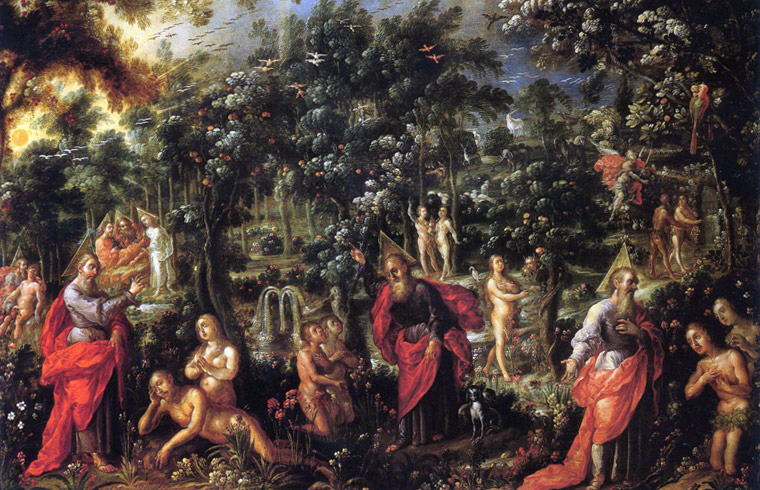

Adam and Eve in Paradise (3.6.18) also hangs with The Deluge, the chapel of the Puebla Cathedral. The painting is also filled with impending darkness of excessiveness, and interest in earthly pleasures instead of heavenly salvation. The garden has become overgrown with dark, foreboding trees as the sky begins to darken, small scenarios of biblical stories interspersed on the canvas. Villalpando masterfully used color on the naked figures bringing dimension and movement as they moved in paradise. These paintings proved the ability of Criollo artists to incorporate sophisticated European iconography. Artists like Villapando were in demand, and his patronage increased. He created a vast body of work throughout his lifetime.

Juan Rodríguez Juárez

The work of Juan Rodríguez Juárez (1675-1728) reflected the changes in painting techniques at the beginning of the 18th century, moving from dramatic lighting and bright coloring to a soft luminosity. Juárez was born in Mexico City in a family of well-known Spanish artists. His talent was recognized early in life, and at seventeen, he presented his first major work. Juárez was a master of large, religious altarpieces and individual portraits, especially those of high rank and casta paintings.

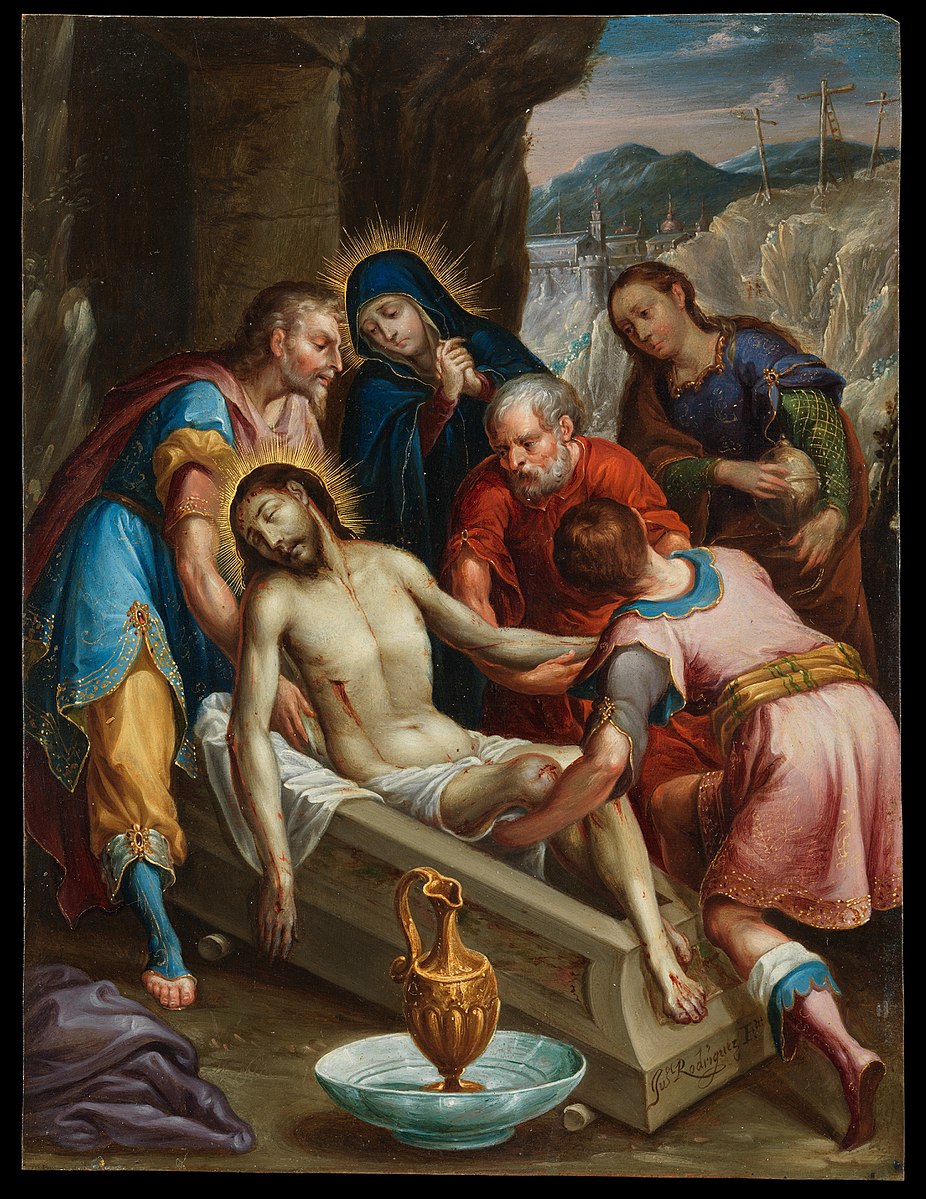

His painting, The Entombment of Christ (3.6.19), demonstrated the brilliant colors he used, especially seen in the variety of blue. The vibrancy of blue shines on the man holding Christ instead of the muted blue of the large bowl. He used dark blue and red on the background figures providing a frame for the seminude light color of the body. The elongated body of Christ filled much of the image and moved the viewer across the diagonal plane.

Miracles of Blessed Salvador de Horta (3.6.20), renowned for performing miracles, depicts the saint healing the sick. He is portrayed as standing and blessing the wounded man seated on the ground. The concepts were probably based on a print by Rubens and similar to a painting made by Juárez's grandfather. Juárez added an image of Mary watching from above. He used loose brushstrokes to define the multiple textual elements; the pale, sickly skin of the injured man, the rough feel of Salvador's robe, or the flatter, distant sky.

_LACMA_M.2008.32_(1_of_4).jpg?revision=1)

The Spanish Crown named a Viceroy to rule over New Spain, a man from a noble family and generally an officer in the military. Fernando de Alencastre Norona y Silva was the 1st Duke of Linares and served as Viceroy from 1711 to 1716. It was customary for an artist to paint the ruling leader. However, to be commissioned to paint the high-ranking Duke of Linares was an honor and only awarded to exceptional artists. Juárez was judged to be an extraordinary portrait artist. Juárez positioned the (3.6.21) duke turned ninety degrees in the central axis of the configuration and dressed in the new French style, complete with a blue jacket and Bourbon wig. After the 1700s, a strong French influence was found when the French Bourbon dynasty took the Spanish throne and controlled the colonies of Latin America. The Duke of Linares was the first French-lineage Viceroy to be portrayed in French clothing as the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The figure is imposed against the dark background, and although his clothing is dark blue, the texture of the material is evident.

Juan Correa

Juan Correa (1645-1716) was born in Mexico, the son of a Mulatto doctor from Spain and a Morena Libre (a freed black woman). He was one of the few artists of a racially mixed background to achieve fame. Being a successful artist and painter was generally limited to those from Spain or a Criollo. The Spanish authorities viewed the Criollo sense of identity as a threat. Artists who identified as Criollo were often passed over for commissioned Viceroy portraits. Correa produced a substantial body of work during his career, including immense mural-sized canvases for the cathedral in Mexico City. He incorporated local Mexican concepts in his work, his use of color distorting the anatomy of figures and elements of Indigenous art.

"The image of the Virgin of Guadalupe was a national symbol. Her miraculous appearance identified God's approval of the new nation, of the friars' apostolic missions, and of the deep piety of the colonists."[6] In all of her different forms, Paintings of the Virgin became an important cultural image, a conciliator between God and humans. The Woman of the Apocalypse (3.6.22) depicts the Virgin based on the standard iconography of Mary found in the bible, "clothed with sun, with the moon under her feet and on her head a crown of twelve stars" (Revelation 12:1). The archangel Michael stands beside her, ready to do battle, and the baby Jesus is carried by two angels.

La Pascua de Maria (3.6.23) depicts Christ, holding the banner of St. George after the resurrection, appearing before Mary. Both images demonstrate Correa's figures with prominent and muscular arms, meticulously detailed hands, and some areas thick with elongated fingers. He also presented the skin with an iridescent look. Correa's portrayal of Mary typically detailed eyelids to appear heavy, eyebrows pitched to represent anguish with a long, straight nose. He gave Mary an entreating position, whether looking down or up. Interestingly, the child held aloft has prominent African features, probably related to the artist's lineage.

The church in Mexico was the primary source of commissions for art in the grand churches with sumptuous altars. Other artwork was also in vogue; devotional objects for the home, folding screens, portraits, metalworks, and ceramics were all in demand by the elites. Homes decorated with artwork were a demonstration of their wealth. One major element in high demand was the biombo (3.6.24) or folding screen similar to those found in Asia. Correa painted a biombo representing four parts of the world; Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Europe, focusing on Europe. Three of the continents have generic figures representing the people, while the figures in Europe are King Charles II and Marie Louise of Orleans. Charles has his back to America, his toe balanced on the word Europa, observing Africa and Asia as the next potential regions to colonize. Asian influence significantly increased at this time.

Twice a year, Manilla galleons traveled from the Spanish-controlled Philippines to Acapulco, Mexico. Japanese style folding screens (byobu), blue and white pottery, and mother of pearl objects arrived in Mexico. Elite homes often had folding screens made of a different material than the Japanese screens, incorporating local scenes. The biomombo, Folding Screen with Indian Wedding and Flying Pole (3.6.25), portrays Indigenous activities, log juggling, the dance of Moctezuma, and the flyers or voladores. Elite Spaniards and Crillos are shown admiring this local village scene.

Most homes had some type of locally made blue and white pottery. The blue and white pottery emulated the Asian porcelain; however, the clay was local to the Americas (3.6.26) with different properties than Asian ceramics. Interestingly, Moorish designs are also often incorporated.

The mother-of-pearl was used in enconchado (oil) paintings (3.6.27), encrusted with slivers of mother-of-pearl inlay and covered with lacquer. The European medium of oil painting, the technique and material of enconchado from Asia, and the subject matter of the Virgin of Guadalupe, were types of work representative of the synthesis of European, American, and Asian cultures.

José de Ibarra

José de Ibarra (1685-1756) was born in Mexico and considered one of the most prolific painters, creating mostly religious images for the cathedrals. He was a follower of Juan Correa and collaborated with other painters, especially Miguel Cabrera, becoming part of the artists who advocated for an official art academy as early as 1753. Open spaces and a softer palette characterized his work. Ibarra's version of Virgin of the Apocalypse (3.6.28) portrays Mary holding Jesus, rising above the endless turmoil she leaves on earth. Her dark blue robe twisted vertically and gave her upward movement against the light, luminescent sky, assisted by the angels and God. Those left below are a mixture of dark colors and the contrasting skin of the cherubs who hold different floral representations of the church.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel of Guatemala (3.6.29) uses somber colors to depict Mary in her role as Our Lady of Mount Carmel, a notable devotional figure in Latin America. The faces of cherubs appear through the dark background. Ibarra left a significant amount of the canvas simply filled in with a gray-brown color bringing the figures forward in a highly dimensional view.

Miguel Cabrera

Miguel Cabrera (1695-1768) was born in Oaxaca, a Mestizo (a person of Indigenous and European descent) whose parents were unknown. After receiving training, he worked on altarpieces in churches before gaining the support of wealthy patrons and becoming a favorite artist for one of the Archbishops. Although many of his works are religious, he painted his patron's portrait, Don Manuel José Rubio y Salinas, Archbishop of Mexico (3.6.30). The archbishop is clad in a muted red cappa magna (grand cape) against a dark baroque-style chair; the trappings of his office – a crucifix, miter, and staff – surround him, accenting points in the painting. As his reputation grew as one of the finest painters in Mexico, Cabrera was instrumental in establishing a formal academy in Mexico City. It eventually became known as the Academy of San Carlos when it became fully functional in 1785. Spanish King Carlos III appointed Jeronimo Antonio Gil as the first director.

One of Cabrera's famous religious paintings was the Virgin of the Apocalypse (3.6.31), a painting full of dire events described in a biblical story from the Book of Revelation and the world's end. As described in the story, Cabrera included the battle between the dragon and the archangel Michael. The Virgin was dressed in a dark blue gown positioned in the center, the darker blue focal point visible in the lighter sky, her head surrounded by the customary twelve stars. Cabrera's muted palette muted brought a dark, moody feeling to the painting.

Figure \(\PageIndex{31}\): Virgin of the Apocalypse (1769, oil on canvas 340 cm x 352 cm) Public Domain

Secular Portraits

Portraits were very popular in colonial Latin America. Portraits of nobles, other genres, including women, and castas paintings, all communicated information on race, class, and social status. One way to convey status was through dress; for example, white powdered wigs and blue jackets were typical for the French Bourbon dynasty, while the previous Spanish Hapsburg dynasty wore somber black capes. Indigenous individuals are often portrayed wearing a rebozo or striped shawl.

The portrait of Doña Maria de la Luz Padilla y Cervantes (3.6.32) by Miguel Cabrera portrays European Baroque style with her elaborate clothing and various accoutrements displaying her status. Like other European portraits, she stands in front of the drape. The closed fan in her hand symbolized a maiden – a woman who is not married and is available. Her elaborate dress dwarfs her body, demonstrating her wealth and European lineage, especially with the bustier and lace ruffles. A decisive French influence is visible via the beauty mark on her temple, known as a chiqueadores – in the stylish mode of the day. These beauty marks were also a European status symbol of the time.

Missing characteristics in Doña Maria de la Luz Padilla y Cervantes' portrait are a coat of arms or a cartouche with text. Although artists followed the European style of portraiture, often incorporating coats of arms, more unique to portraiture in Latin Americas was added text in cartouches or text boxes. Miguel Cabrera's portrait of Don Juan Xavier Joachin Gutiérrez Altamirano Velasco (3.6.33) incorporated a lengthy biographical description of the man portrayed directly on the painting in the lower right-hand corner. He stands in a European contrapposto stance, wearing the French and Spanish fashions of the day. However, the textbox places this portrait in the genre of portrait painting in Latin America.

Religious Portraits: Monjas Coronadas

Text and imagery went together and created another critical genre of art often found in the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Popular paintings were portraits of nuns when they took their final religious vows to a convent. By the eighteenth century in Mexico, it was customary for families of Spanish and Criollo women to join local convents to commemorate the occasion by commissioning portraits of their daughters dressed and adorned in a sumptuous Baroque manner. These "profession portraits," called Monjas Coronadas (crowned nuns), are striking in their ostentation and material display. Although there are some variations based on the particular order of the convents, most Monjas Coronadas displayed the same general features. Portraits of Sister María Antonia de la Purísima Concepción Gil de Estrada y Arrillaga (3.6.34) and Sor María Ignacia Candelaria de la Santisima Trinidad (3.6.35) include lengthy autobiographical information. The nun's name, her parent's name, the convent she confessed to, and her age were all outlined. Monjas Coronadas included numerous physical, religious references. One nun wore a striking crown associating herself with the queen of heaven. An escudo de monjas, (nun's badge was a sizeable plate-shaped piece of jewelry with religious imagery related to her religious order. The palm frond with flowers symbolized victory and triumph, and an image of the baby Christ child represented their future husband. Their sumptuous dress demonstrated the relationship to a specific religious order. Nuns who lived especially important lives in the convent or those who rose to the ranks of abbesses were painted in death, adorned in their crowns and flowers.

In a parallel fashion, the families of Indigenous women also commissioned portraits of their daughters before the profession of vows. However, there was a noticeable contrast between Indigenous professional portraits and Monjas Coronadas. Indigenous profession portraits depicted young women typically dressed just as splendidly as the Monjas Coronadas in a different and secular manner. Unfortunately, these portraits are very rare. Both the Spanish and Indigenous profession portraits were created for similar reasons; the differences between the portraits appear inherently linked to issues of race and status in New World society. The markedly different nature and appearance raise the question of why the Indigenous women chose not to represent themselves in the same fashion as the Spanish in the moment of their profession to a religious establishment.

Casta Paintings

Race, class, and social status in the New World were of great concern and formed another type of portrait painting. Casta pastings were part of a genre of painting popular in the 1700s in New Spain, representing racially mixed categories of people between Spaniards, the Indigenous population, and African slaves. Identification of the mixed-race types was found in official documents, for example;

- Mestizo – the offspring of an Indigenous person and a Spaniard

- Castizo – from a Mestizo and a Spaniard

- Mulatto – from a Spaniard and an African

Multiple other classifications were defined, reflecting the diversity of the population. Historians are conflicted on how rigid the classifications were and exactly how they were used. Casta paintings most notably link the theory of the purity of blood to status in society. Racial status had legal ramifications and social interaction restrictions; however, the system appeared somewhat fluid.

These paintings were made primarily for patrons of the upper class. They were visual expressions of the complex process based on intense cultural and biological mixing in Latin America during the colonial era. Additionally, the Enlightenment fueled casta paintings to find rational explanations for the natural world around them. Great anxiety existed about a person's place in the very complex colonial world. The biological mix or race generally dictated one's place in the social structure. Between the intermingling of various races and the competition between individuals from Spain and the Criollos, historians believe Criollos were the patrons of these paintings to establish their station in the social hierarchy of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The peninsular Spaniards were considered the most elite in society and tried to limit the Criollos with taxation and government employment. The Criollos saw themselves as superior since they were born in the wealthy and vibrant Viceroyalty – the economy in the Old World was relatively stagnant.

Most paintings were created as sets, on one canvas, or spread out between sixteen canvases. Each image depicted a family group with parents of different races and the biological child of the parents. They are also hierarchically arranged – those of pure race on top and ending with the unconverted Indigenous. As Illona Katzew, the leading expert on casta paintings explained in a 2004 exhibition on Castas paintings, "Spaniards and creoles used the caste system to rank people according to their purported percentage of white, Indian, or black blood, with its goal to show that certain racial mixings were more positive than others. Because Native Indians were considered, 'new Christians' and thus Spaniards' equals, the system contended that if Indians kept mixing with Spaniards, their offspring could become entirely Spanish on the third generation."[7]

The casta painting (3.6.38) is a set of sixteen different classifications of racially mixed people, dressed according to their status and performing appropriate tasks. These paintings were common, and the first position belonged to a Spanish man, a purported elite Indigenous female, and their offspring, in this case – a Mestizo, a label under each image stating the lineage and the racial mixture. The images in each square were judgmental, not necessarily an accurate depiction of life. Spanish men were seen as professionals, Mulattas as cooks or seamstresses, or Mestizos as tailors, except those from Spain were the elite in control.

One of the well-known artists of casta paintings was Miguel Cabrera. The first 16 paintings (3.6.39) illustrate a Spanish father, a Mestiza mother (mixed Spanish-Indian), and the Castiza daughter. The clothing demonstrates the couple's status; he is wearing the wig and jacket of a high-placed man, and the woman, although wearing a headband and braided hair, is dressed in a lace and silk dress befitting their financial status.

The young girl also wears an elegant dress, a child of leisure. In the second painting (3.6.40), the Spanish man wears the hat of someone in the country; the woman is labeled a Negra in the image, their child a Mulatto. The clothing is simpler in the second painting; the young girl still has ornamentation on her dress, the man has multiple metal buttons on his jacket, still a man of means. The woman is painted in the shadows except for her multi-patterned floral skirt, featureless, status undefined except by the basket she carries. She also wears a rebozo, just under the shawl that covers her head.

Figure \(\PageIndex{40}\): Pintura de Castas de español y negra – Mulata (1763 oil on canvas) CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{40}\): Pintura de Castas de español y negra – Mulata (1763 oil on canvas) CC BY-SA 4.0Andres de Isla

As seen in the lengthy biographical cartouches in secular and religious portraiture, text and imagery also support each other in casta paintings. Sometimes in Casta paintings, fruit is labeled the way people are labeled. Andres de Isla (active ca. 1753-1775) completed a set of casta paintings (3.6.41), labeling both people and fruit. In the upper right-hand image (sets of 16 are very rare when they are separate canvases) is a bowl of fruit common to the country with numbers corresponding to the list of fruits at the top of the painting. In the different races, an African woman is shown as a negative stereotype – angry and beating her Spanish husband, as their mulatta daughter intervenes. At times casta paintings depicted racial stereotypes and other times (Miguel Cabrera's set) harmonious unions.

Casta-like paintings in Peru

Although paintings depicting racial types were more common in Mexico, the Viceroyalty of Peru also demonstrates a racial classification painting. In the painting, Union of the Imperial Inca Descendants with the House of Loyola y Borja (3.6.42), a couple on the lower left were married. The woman is from Inka royal lineage (shown in the upper left), and the man is related to Saint Ignatius of Loyola and a conquistador from the Loyola family. Their daughter is getting married (upper right) and posing (the lower right) with her husband, from the Borgia family and Spanish nobility. This painting is an example of one's status – imperial Inka - used to strengthen Spanish control. The text in the cartouche underscores the events declaring the marriages joined the royal Inka to the houses of Loyola and Borja.

Vicente Alban

In Vicente Alban's (1725-unknown) portrait A Lady with her Black Slave (3.6.43), different races are visible; however, the lady demonstrates her status by owning a black slave dressed in fine clothing. All of the examples depicted display marriages of Spanish and Indigenous figures, the lineage and heritage of each culture in the background. Clothing assists in documenting which race is depicted because clothing and a person's appearance played a considerable role in colonial Latin America.

Paintings as a Document

Painting the complex diversity and prosperity of the New World is viewed in images documenting scenes familiar in New World cities as in the Visit of the Viceroy to the Cathedral in the Plaza Mayor de la Ciudad de México (3.6.44) painting. Along with the Viceroy in his chariot, various classes of society are represented in the marketplace in activities associated with their social status. People are buying goods; others are selling goods in permanent stalls, on the street, or walking around with wares on their backs. Clothing also denotes the Spaniards, the French, the Indigenous, and their various social statuses. The overall image barely focuses on the visit of the important viceroy, documenting commerce, different activities, and the buying and selling of goods in the diverse culture of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The economy in the Viceroyalty of New Spain appeared to be booming.

Artists in the second half of the 17th century focused on the past and the conquest of the Aztecs. The Conquest of Tenochtitlan (3.6.45) is based on a series of paintings titled Conquest of Mexico. Although this painting, and the others in the series, are grounded in specifics, people viewed the conquest differently 150 years after the event. Motivated by a romantic view of the conquest, the months-long wars were distilled into a feeling of one event. Hernán Cortés is labeled, and the cartouche or textbox categorizes the labels.

The Indigenous population wore feathered skirts in the Meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma (3.6.46) painting. However, featherwork was an art of the Indigenous people; they did not wear feathered skirts. However, 150 years after the conquest, Europeans continued to portray Indigenous people clothed in feathered skirts.

Antonio Rodríguez

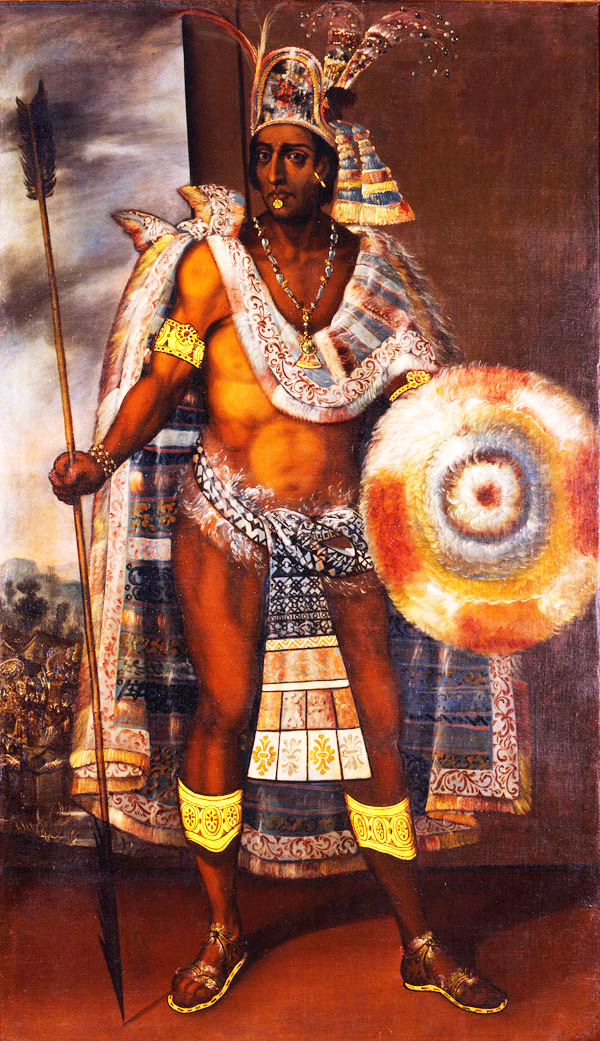

One of the most beautiful and eye-catching paintings was attributed to Antonio Rodríguez (1636-1691) of the colonial period, a painting documenting the great Aztec ruler, Moctezuma II. Although painted long after Moctezuma was dead, this image portrayed him more realistically than other paintings at that time. Here, Moctezuma (3.6.47) is dressed in an exact depiction of pre-Hispanic attire. Rodríguez used earlier works to document a more realistic appearance of the Emperor. The gold bands on his arms and legs in the portrait are stunning. When the actual painting is viewed in person, the use of two-dimensional flat gold enhances the three-dimensional look of his well-defined body. Interestingly, the back of this painting has text that explains this painting was sent to the Grand Duke of Tuscany – a member of the Medici family and is in Florence, Italy, today.

Sculpture in Peru

One notable painting documents a devastating earthquake in 1650, which struck Cusco. The painting illustrated the central plaza in Cusco, Peru, with residents parading a statue from the local cathedral around the city to stop the 400 aftershocks following the major earthquake. In the painting, the actual statue known as Christ of the Earthquakes (3.6.48) (Taytacha Temblored in Quecha, in Inkan) is put on parade annually on Easter Monday. Christ of the Earthquakes is also the patron saint of Cusco; the statue is believed to protect the city from earthquakes. The statute's origin is unclear; however, it is thought the sculpture was shipped from Spain to Peru in the 16th century. In the painting, the statue is clad in a notable dress and red ñuk'chu flowers. Historically, the ñuk'chu flower was sacred and used in religious ceremonies to appease Incan deities and keep earthquakes at bay. In 1950, an earthquake struck Cusco again, damaging Santo Domingo, the Spanish church built above the Qorikancha.

Cusco School

As seen in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, many of the significant developments in the arts occurred in the Viceroyalty of Peru. However, one important historical event occurred in Peru, causing a substantial consequence on art. Just as in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, Peru had a guild of artists. However, Spanish and Criollo artists petitioned Cusco's royal representatives to erect their arch for the famous Corpus Christi procession without the help of the Indigenous guild members. Although the guilds were initially established to be free from racial prejudices, that wasn't exactly the case. The authorities granted the request to the Spaniards and Criollos, which angered the Indigenous artists. Subsequently, the Indigenous artists broke from the guild, identified themselves in local terms, and formed the Cusco School. The Cusco School followed an earlier style of art, something more akin to Indigenous styles.

Statues like Christ of the Earthquakes, when not in procession, are kept in chapels near the aisles in Cathedrals. If these statues were perceived to have miraculous powers, artists wanted to paint the image. They touched the painting against the original figure, thereby transferring the miraculous properties, and shipped the painting and its miraculous capabilities to another town. The Cusco school painting, Our Lady of Cocharcas (3.6.49), is a painting based on the original sculpture. Another characteristic of Cusco school painting is the abundant use of gold, evident in the dress on Our Lady of Cocharcas. The generous use of gold leaf placed over the three-dimensional images is called brocateado. The gold leaf flattens those parts of the painting covered in gold, while the other parts of the image look three-dimensional. The gold leaf gives the painting an appearance of a heavenly, mystical effect.

One of the more unique paintings of the Cusco school incorporated a famous mountain in the Viceroyalty of Peru, the Mountain of Potosí, where the Spanish mined for silver. The connection between the mining of metal and the Virgin Mary is shown in the painting, The Virgin Mary and the Rich Mountain of Potosi (3.6.50). The Virgin Mary's dress is literally the mountain itself. God the Father and Christ are crowning her; the religious and secular authorities are shown below. These secular authorities underscored their rule over the region and the silver mined in the area. The Cusco School artist, however, may have had alternative intentions. Pacha Mamma was an Incan deity – mother earth. Perhaps, the Cusco artist was performing an act of resistance by engulfing the Virgin Mary in "mother earth." The artist attempted to understand the importance of the Virgin by relating her to their preconquest religious deities.

Although artists brought the traditional European ideals of sculpting, painting, and architecture, the different cultural influences of the Indigenous populations and intermarriages, changed the aesthetics of tradition into new models of art, pictorial styles, ornamentation, and structural formats. Local materials added to the mix formed the identity of a new national community, overlapping and integrating artistic techniques and identity still in use today. The Catholic Church and its mixture of different organizations provided the support and inspiration for much of the creative work in Mexico. Distinctive biblical stories or tales of saints and other church heroes brought a wealth of ideas and iconic images for artistic creativeness.

[1] Bondi, C. (2011). Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal, Shaping an Identity: Cultural Hybridity in Mexican Baroque Architecture, 5(5), p. 449.

[2] Bondi, C. (2011). Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal, Shaping an Identity: Cultural Hybridity in Mexican Baroque Architecture, 5(5), p. 450.

[3] José Moreno Villa (1986). Lo mexicano en las artes plásticas [The Mexican in the Plastic Arts]. Mexico: Economic Culture Fund. Retrieved fromhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_San_Francisco_Acatepec 1

[4] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/pinxit-mexici

[5] Paz, O. (1990). Mexico Splendors of Thirty Centuries, Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, p 334.

[6] Donahue-Wallace, K. (2008). Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821, University of New Mexico Press, p. 142.

[7] Katzew, Ilona. Inventing Race: Casta Paintng and eighteenth-century Mexico. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2004.