3.7: American Colonial (1700 – 1800s)

- Page ID

- 121512

Introduction

When the Europeans started to colonize North America, the weather and topography were familiar, a new and unspoiled land where they could begin a different life under new religious laws and governments. Diverse religious groups installed governments according to their beliefs; strict zealots in New England practicing severely restricted concepts or those believing in aristocracy and large estates in the southern territory. Portraits, a primary style of painting in Europe, were imported and became a dominant style in the colonies. Skilled artists moved from Europe to the new land as cities and colonies became economically strong with a growing affluent society. England began to impose additional taxes and new laws. Yet, the colonies had no representation in the English government, bringing the colonists to the brink of war, "no taxation without representation," and finally, the revolution.

The early settlers relied on European art standards, posing the subject, and painting clothing in portraits. Population centers like Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston became meccas for artists from Europe and those born locally, creating new styles. The Spanish inhabited the coastal areas of the west, and art was based on the Spanish Catholic Baroque; the territory of Louisiana was controlled by the French and Rococo style, while the east coast was under the influence of England and the Dutch aesthetic principles, the strongest and most long-lasting. Art in the northern colonies was structured based on constricted religious beliefs, while the southern colonies built large plantation estates filled with elegant furnishings and paintings. Regardless of location, all of the art was Eurocentric; they had little contact and were not influenced by the traditions and styles of Native American art. Slavery was active in all thirteen colonies, and the people forced from Africa as slaves also brought their art with them. Personal art of vessels, small drums, or baskets survived from early New England slaves onward. Many slaves toiled on public works or large plantations, bringing their craftsmanship as cabinetmakers, ironworkers, or carvers.

By the time the republic grew and became independent, local artists developed and expanded art beyond portraits. One of the favorite subjects for artists were images of the newly emerged military and patriots; Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, and others. Traveling artists painted portraits of ordinary people. Art went beyond painting, creating new styles of furniture, silverwork, and architecture, designing and making artwork for the new country.

Folk Art Paintings

Some of the early artists in the colonies were considered folk artists, commonly self-trained, acted as an apprentice, or were minimally instructed. Their art was used to decorate homes with single or family portraits characterized by a more straightforward, naïve style and generally, did not follow rules of proportion or perspective. Many folk artists had limited resources and were itinerant, traveling from place to place depending on the location of the individual who wanted a portrait.

Ruth Henshaw Bascom

Born in Massachusetts, Ruth Henshaw Bascom (1772-1848) married a minister and spent her time traveling and supporting his religious endeavors, only starting her artwork later in life. She was an avid record keeper. Many of her diaries survived, giving historians a look at her life, the local community, the weather, information about the art supplies she purchased, and how much they cost. Very few notations were written about income from specific artwork; however, her diaries indicate she created over 1400 pieces of art. She lived comfortably on the average income; however, art supplies would be costly; depending on the style of frame and the glass, and she generally charged one to three dollars or bartered a common practice. As she traveled, she painted and believed idleness was not a proper behavior and noted, "I sketched Miss H. Goulding and two images for little S. Booker and L. Jones – for want of other means to employ my leisure."[1]

Bascom used pastels and crayons to create her profile images, generally life-sized from the bust upward for adults and from the waist for children. In the image, Cynthia Allen (3.7.1) wore a typical hairstyle, a bun on the back of her head and dangling curls in the front (frequently called spaniel curls). The sheer shawl on her shoulders was an ordinary fashion item. The image is a life-like yet straightforward copy of the people and a common technique for the itinerant artists of the time.

Rufus Hathaway

Rufus Hathaway (1770-1822), from Massachusetts, was self-educated as an artist, moving around and working in multiple locations in Massachusetts. In 1796, he studied medicine and became a doctor in a small town in the state. One of his most well-known portraits, the Lady and Her Pets (3.7.2), is a painting with more detail than most folk art yet flattened in perspective. The bottom of her dress is oddly placed, her shoulders out of proportion, her nose excessively long. As she poses with two birds and her cat, two odd feathers burgeon from her hairstyle. Feathers placed in a woman's hairstyle were common in French painting; however, they were not thrust upwards, instead were elegantly positioned. Hathaway was a prolific artist from 1790 to 1796, painting very little after becoming a doctor.

_-_Rufus_Hathaway.jpg?revision=1)

Susanna Paine

Susanna Paine (1792-1862), one of the early painters, was also considered an itinerant artist, traveling around the countryside creating portraits for commissions, a problematic occupation for a single woman. She married and then divorced her husband because of abuse, and to earn a living turned to painting, generally using oils on wood and occasionally pastels. She rented lodging and started to paint, asking her landlady to look at her work; the woman was so surprised she spread the word to others. Paine wrote in her book about the people who came to view the paintings recording, "…They entered my 'sanctum' with eager looks, to see whither [sic] – a woman could paint a likeness? When lo, they all applauded, beyond my most sanguine hopes – or expectations."[2] Eliza and Sheldon Battey and their son Thomas Sheldon Battey (3.7.3) were painted with oil on a wood background. They are seated on a settee against a backdrop of dark red drapes, dressed in clothing representing his status as a successful businessman. The intricate details of the woman's hat and collar and the ruffles on the boy's collar demonstrate the ability of Paine to paint realistically.

Joshua Johnson

Joshua Johnson (c. 1763-c. 1824) was born in Baltimore or the French West Indies, although little is known about his background. The Baltimore County records list the sale and manumission of Johnson as a mulatto, the son of a white man and a black slave woman. After Johnson was freed, he may have worked as a furniture decorator before becoming an itinerant painter of portraits. No records exist of his education; however, he did place advertisements in two papers. He described himself as "a self-taught genius who had experienced many insuperable obstacles in the pursuit of his studies, it is highly gratifying to him to make assurances of his ability to execute all commands with an effect, and in a style, which must give satisfaction."[3] Baltimore was a city with a significant number of freedmen and fewer slaves, an atmosphere helping Johnson succeed.

Johnson did not sign or date his work except for one portrait; however, over eighty works are attributed to him. Johnson followed the same format in painting his images; the faces are stiff, in a three-quarter position, gazing forward. He painted against plain backgrounds with some sort of window. The Westwood Children (3.7.4) follows the standard methods Johnson used; the children are standing in front of the bland brown wall, an open door or window on the side revealing the outside. Johnson also added some sort of prop to the figures, and here the children hold flowers and a basket. Their faces have an adult quality as they gaze forward.

Sarah Goodridge

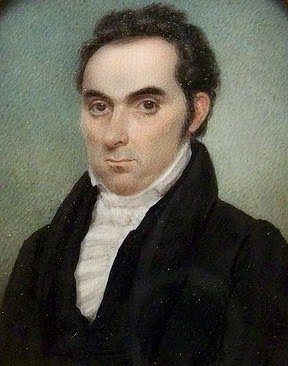

Sarah Goodridge (1788-1853) was raised on a farm with little opportunity for art supplies and learned to draw using sticks in the sand on the kitchen floor. As a teenager, she moved to Boston, studied with a painter, opened her studio, and became one of the most productive miniatures painters. Goodridge developed a friendship with Gilbert Stuart and his daughter Jane, having him critique her work. Goodridge was so successful, that she frequently painted three portraits in a week of many Boston notables. Her preferred medium was watercolor painted on ivory.

One of her favorite customers was Daniel Webster. Historians believe Webster, a politician, who was married and had children, carried on an affair with Goodridge for years. Over multiple years, she painted several portraits of him while they also carried on a correspondence. However, when his wife died, he remarried a wealthy woman, remained a senator, and still continued to visit Goodridge. The painting Daniel Webster (3.7.5) was one of the images she did of Webster, dressed in a typical black coat and ruffled shirt, but whose expressive eyes seem to stare back at the painter as the rest of his face remains stoic.

_by_Sarah_Goodridge.jpg?revision=1)

Henrietta Johnston

Henrietta Johnston (ca 1674-1729) was believed to be from France initially, and the family migrated to England, where she married. In England, she started drawing with pastels, creating portraits of English society she knew from her husband's family. With her second husband, she moved to the area of South Carolina, becoming the first known female artist and portraitist in the southern part of the colonies. Her work usually depicts the person from the waist upward, the male person in street clothes, and the female in a chemise.

Occasionally Johnston went to New York, and there she completed the portrait of Anna Cuyler (Mrs. Anthony) Van Schaick (3.7.6), the daughter of the mayor of Albany. The image was typical of Johnston; the facial appearance of Anna is vague, perhaps nostalgic, her face and hair unadorned and straightforward. The chemise may have been made of good material; however, it also seems plain, unlike those with elegant lace and satin.

_Van_Schaick.jpg?revision=1)

Fine Art

Fine art, or what many consider academic art, is usually found in museums, public spaces, books and thought of as "art." Most of those considered fine artists were educated in universities or sophisticated apprentice programs. Fine art brings the prestige of history and quality, supposedly things we should know about and appreciate, and sold at high prices.

Charles Willson Peale

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), born in Maryland, started as a saddlemaker before traveling to England to study art. In the Continental Army, he served as an aide to Washington and became a prolific painter of Washington images. Of his seventeen children, five were also well-known artists and appropriately named after old master artists. He painted numerous prominent colonial notables and added a gallery to his studio for other art and scientific examples, later including specimens gathered by Lewis and Clark on their expeditions.

The Cadwaladers wanted family portraits for their home and commissioned Charles Willson Peale to paint five different images. Peale had been to England to study for a few years, and when he painted John and Elizabeth Lloyd Cadwalader and Their Daughter Anne (3.7.7), he posed them in the latest trend, people facing each other as though talking instead of looking out at the viewer. The peach John Cadwalader holds in his hand symbolizes one's virtue; his clothing has gold embroidery. His wife wears oversized jeweled earrings and satin clothing, the images signaling the family's wealth.

Gilbert Stuart

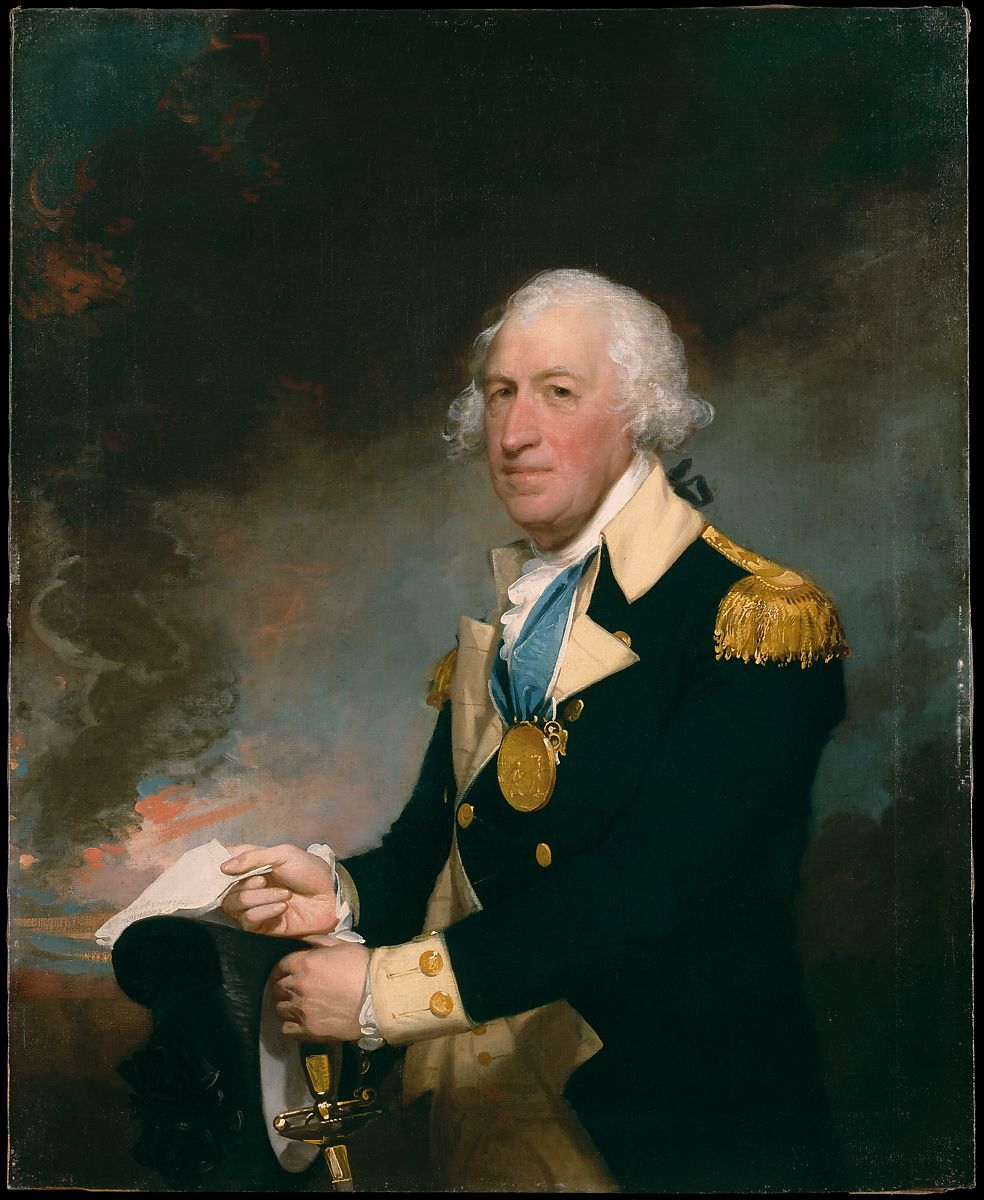

Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) of Rhode Island was deemed one of the most successful of the early portrait painters in the new colonies. He is a prolific painter of over one thousand paintings and is known for his eccentricity. Because of Stuart's severe depression, he did not finish any painting he didn't like. Despite his success, Stuart was always near bankruptcy. John Adams once said of him, "Mr. Stuart thinks it the prerogative of genius to disdain the performance of his engagements."[4] He studied in England, a supposed prerequisite for success, and returned to the colonies to further his career, landing commissions with influential people, including his multiple portraits of George Washington.

General Horatio Gates (3.7.8) was a hero in the Revolutionary war, and Stuart painted his portrait shortly after the Battle of Saratoga, where the general successfully defeated the British. Stuart displayed the striking uniform and symbols of the rank in detail, including the commemorative medal on his neck and the surrender documents in his hand. The painting followed the British style with a background of the battle, the carefully posed figure looking at the viewer.

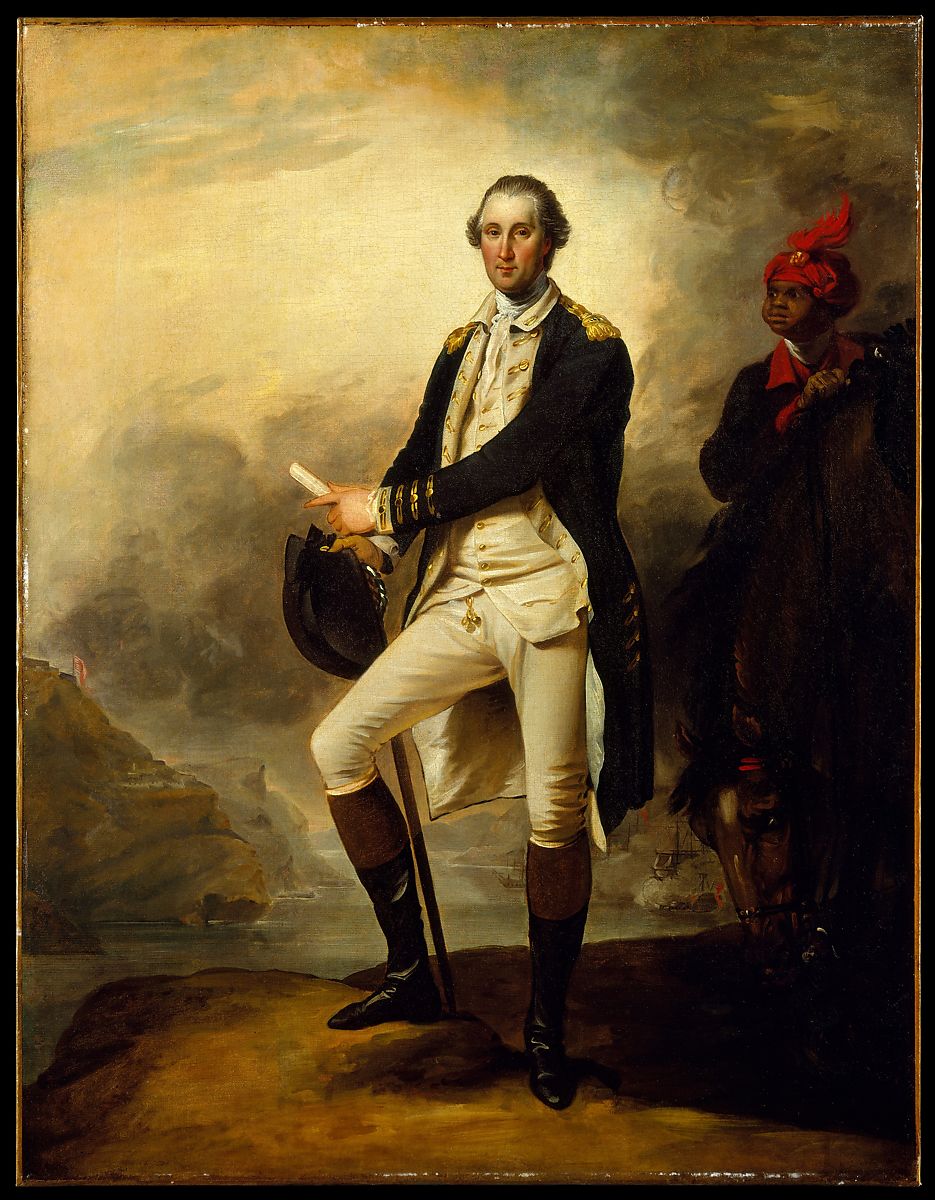

John Trumbull

John Trumbull (1756- 1843) from Connecticut was part of a wealthy family, attending Harvard and serving as an officer and aide to Washington in the Revolutionary War. He traveled to England and studied painting and architecture, gaining a reputation as a painter. Known for his portraits of George Washington, in 1817, he received a commission to paint four different large, historical paintings to be installed in the rotunda of the capitol.

The Surrender of General Burgoyne (3.7.9) depicts the surrender at Saratoga of the English general to American General Gates, a turning point in the war. General Burgoyne would surrender his sword – the familiar symbol of defeat – however, General Gates refused and invited him into the tent for refreshment. The painting displays the dress of each of the various officers and soldiers, the British red coats prominent. The scene is colorful and peaceful, the stance of the men at ease. Trumbull sketched a study of the region, including the large tree on the left to ensure he had the right perspectives, and painted the figures from earlier paintings he had completed.

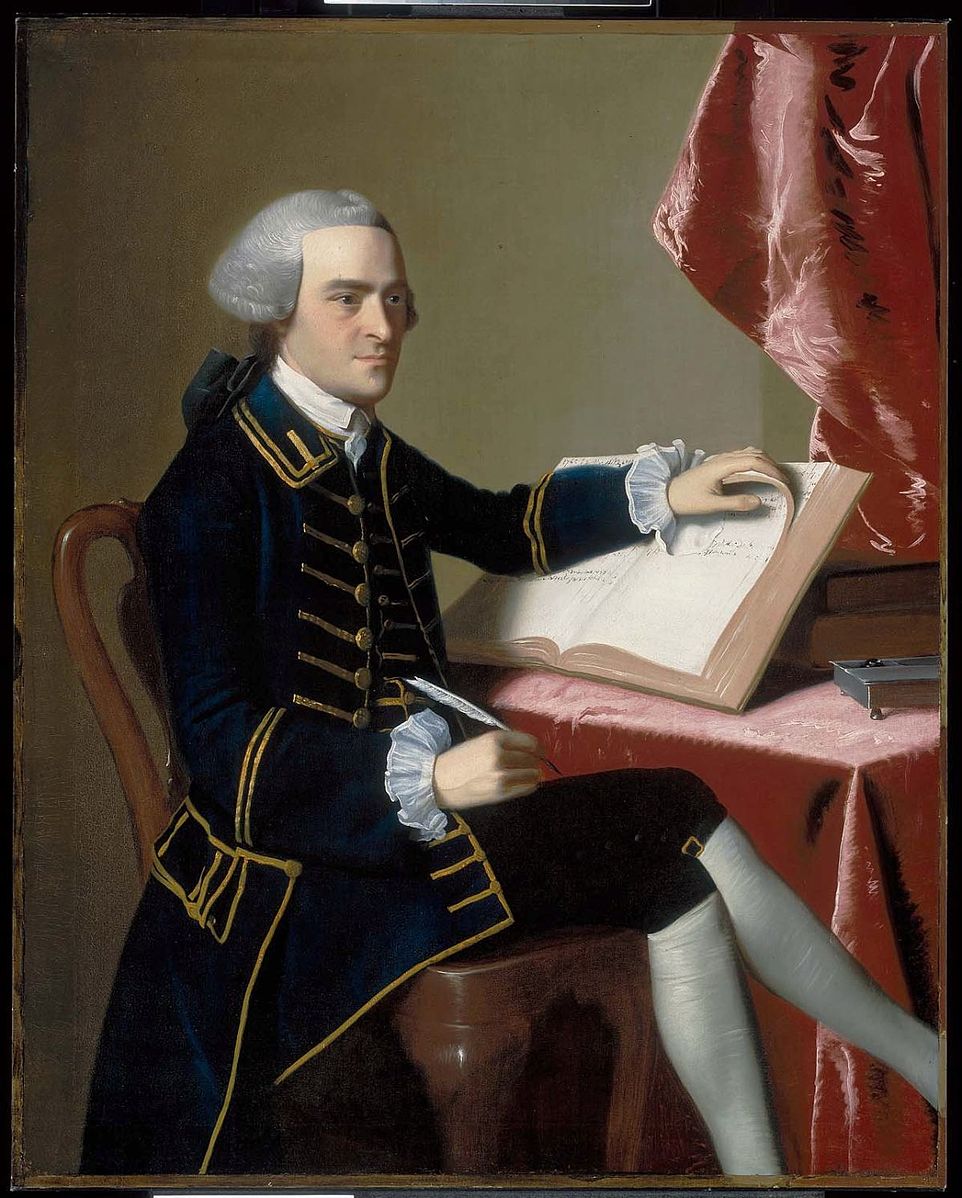

John Copley

John Copley (1738-1815), born in Massachusetts, rose quickly in the world of portrait painters. Copley was fortunate to have a stepfather with a significant collection of prints from old masters and a perfect tool for his education – copy the old masters. In the colonies, his market grew as the wealthy wanted English-style portraits, and with his talent and education, he knew how to compose their images. As the concepts of revolution grew, he changed his ideas and began to portray his patrons in a setting to display their interests or talents, changing the concepts of overly posed English standards.

John Hancock (3.7.10) is the portrait of a man with inherited wealth who commissioned Copley to paint his image. By this time, Copley was posing people in more naturalistic settings, and Hancock is sitting in a relaxed position, pen in hand, writing an entry in the book. He is wearing a bob wig, his coat quite detailed, the gold braid and buttons accenting the plain material. The background is not as dark as the English style and is highlighted with the drapery and table holding the book and inkstand.

George Washington Images

Initially, Washington retreated from having his portrait painted; however, based on his growing fame in battle and later as the president, he grew more patient and allowed multiple artists to create his image. Over time, paintings and sculptures of his likeness have become the most famous early American works of art. The well-known portrait of Washington Crossing the Delaware (3.7.11) in 1776 is an iconic view of the river and Washington's attack on the Hessians. Leutze did not start the painting, using oil on canvas, until 1849, well after the death of Washington. The painting was destroyed in 1942; however, so many copies by other artists were made, the image of Washington's courage still exists today.

The only pre-Revolutionary image of George Washington was painted by Charles Willson Peale, who frequently visited Washington at his home and in battle, painting Washington more than any other artist. Portrait of George Washington (3.7.12) depicts Washington as a lieutenant colonel for the Virginia militia, sent by the British general to protect British settlements in Ohio from the French. Washington was tall and looked impressive in the red uniform of a British officer and tri-cornered hat. Around his neck, he wore the silver gorget, a metal piece initially worn for protection until the 17th century, when it became a symbol of rank and authority.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\): Charles Willson Peale - Portrait of George Washington (2019 oil on canvas 152.4 x 127 cm) Public Domain

When Washington worked as an aide to one of the British generals, he was careful to study how the British comported themselves, especially those with high ranks in leadership positions, noting that appearance was important. When the Continental Army was formed, and Washington was named leader, he wanted the organization to be professional and in proper uniform, ordering uniforms with blue coats and white waistcoats. Each state had its regiment with different colored linings and buttons. Additionally, the uniform defined black tri-corn hats, dark shoes, white stockings, and beige breeches. John Trumbull worked on Washington's staff and painted several images. In George Washington (3.7.13), Washington is standing across the Hudson River with West Point in the background. He is wearing the new Continental Army uniform, standing with authority, his slave in the background. Trumbull used yellow tones as the background to compliment the dark blue coat and buff uniform.

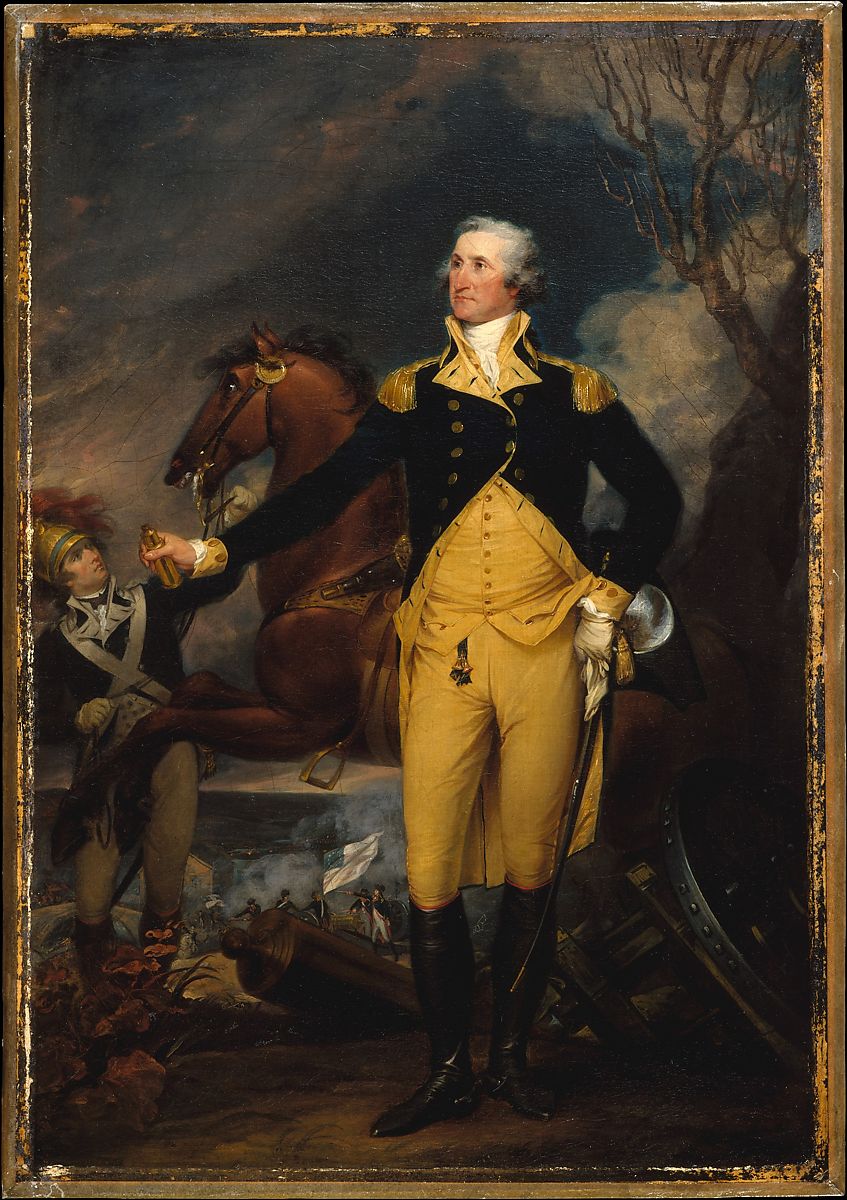

George Washington Before the Battle of Trenton (3.7.14) was painted by John Trumbull with oil on canvas. General Washington appears ready for battle the night before the invasion of Trenton, maintaining his stance of authority, his groom trying to contain the energy of the horse. The light-colored uniform stands out against the dark, brooding sky, his face confident, a spyglass in his right hand as he assesses the battle plan for tomorrow. Trumbull later painted different versions of the same setting, a venue used by other painters of Washington.

After a victory at Yorktown, Washington went to Maryland and stayed with the governor, who was impressed by Washington. He requested, "write to Mr. Peale of Philadelphia, to procure, as soon as may be, the portrait of his Excellency General Washington, at full length, to be placed in the house of delegates, in grateful remembrance of that most illustrious character."[5] Peale did the painting Washington, Lafayette, and Tilghman at Yorktown (3.7.15) and included the figures of Lafayette and Tilghman, adding historical elements of soldiers holding their country's flags.

"I have made in the distance a View of York & Gloster with the British army surrendering in the order in which it happened. And in the middle distance I have introduced French & American officers with Colours of their nations displayed, between them the British with their Colours cased. These figures seem to tell the story at first sight, which the more distant could not so readily do".[6] Washington is seen in his usual confident stance, the powerful general, while Tilghman holds the Articles of Capitulation in his left hand, signed by the British.

In 1814, Dolly Madison heard that British troops were entering Washington, burning the buildings as they marched, and she needed to leave immediately. She quickly secured the official papers and wanted to take the portrait George Washington (Lansdowne portrait) (3.7.16) with her as she fled the White House. The painting was attached to the wall, and with little time left, they broke the frame, extracted the canvas, and fled to safety. Many people painted Washington's portrait; however, this one by Gilbert Stuart remains the emblematic symbol of the president. His sword is sheathed, representing his resignation from the military, and he wears civilian clothing, now the ordinary citizen. The Constitution and laws of the United States lean against the table leg with other books on the table, all demonstrating the new government's support and its constitution. Washington did not pose as himself in the image, only sitting to have his head painted while the rest of the figure was from a model or just created.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=395&height=635)

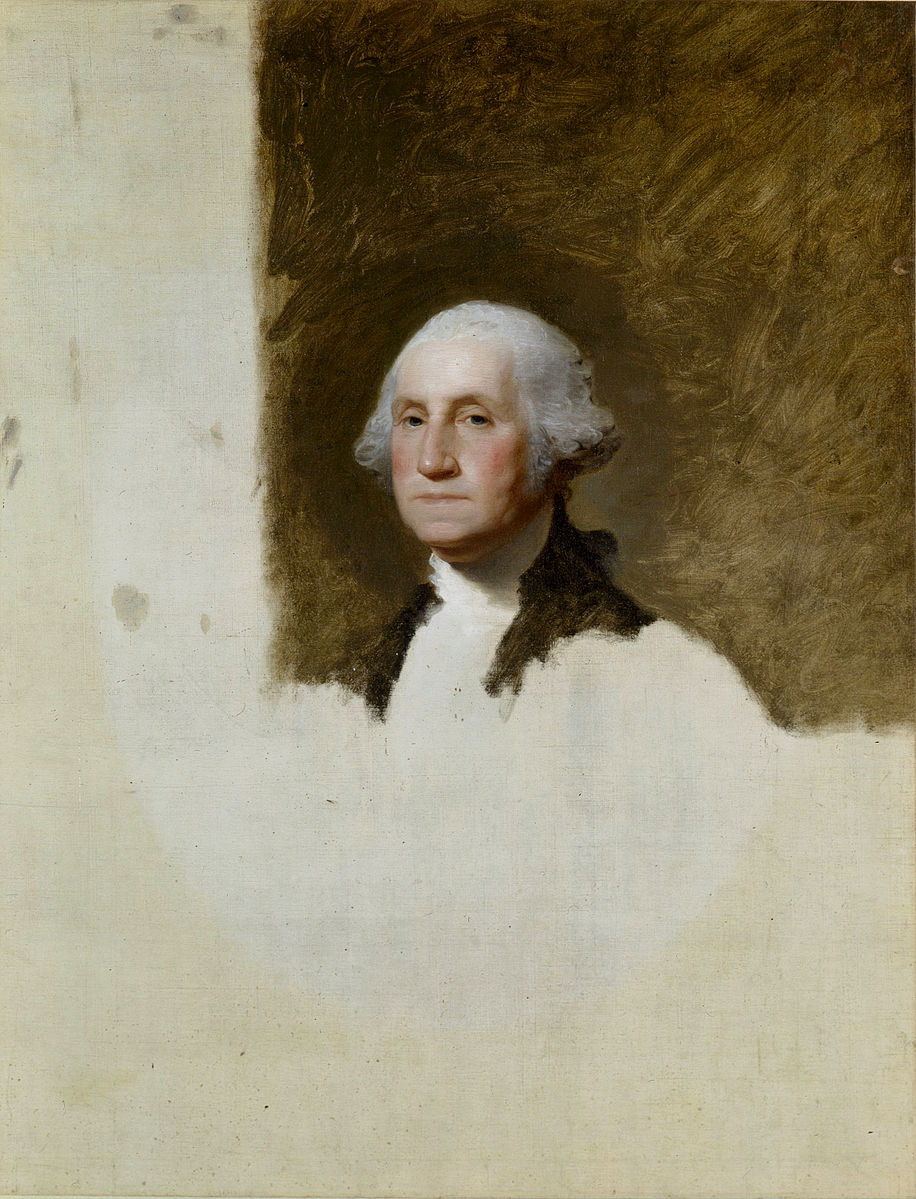

Martha Washington wanted Stuart to paint a portrait of her husband for herself and convinced Washington to sit for Stuart. However, Stuart did not finish the painting, George Washington (The Athenaeum Portrait) (3.7.17), planning to keep it as a reference for other works. The painting is the basis for the one-dollar bill and emblematic of the image of Washington. John Neal, an early-nineteenth-century writer, and art critic, wrote, "Though a better likeness of him was shown to us, we should reject it; for, the only idea that we now have of George Washington, is associated with Stuart's Washington."[7]

The painting, The Washington Family (3.7.18) by Edward Savage has become an icon of the family and Washington. Martha Washington and her granddaughter are pointing to the grand avenue on a map of Washington D.C., now known as Pennsylvania. At the same time, a slave stands behind her, Washington, in military uniform, and his grandson appears to be listening. Savage was known for his ability to paint laces and satins in great detail, as seen in the sheen of Martha's dress and the lace adorning the clothing. However, most historians consider the figures to have a wooden appearance, a little distorted. Each family member seems to be looking at something else in the room, perhaps a result of each person sitting for the painting at different times. In the ample open space in the background, boats float down the river in front of the distant hills, believed to be a representation of Washington's home at Mount Vernon.

According to Savage's own description, the painting combined symbolism with naturalism. Washington's "Military Character" was represented by his uniform, the papers on which his arm rested represented his presidency, and Martha Washington was shown holding "the Plan of the Federal City, pointing with her fan to the grand avenue." The grandchildren were meant to represent the future of the nation. The only figure in the painting not mentioned by Savage was the black servant, perhaps because the presence of slaves was taken for granted.[8]

Silversmiths

The silversmith in colonial times was respected as an artist, frequently thought of as sculptors. Silversmithing was viewed as a luxury occupation; the general population owned pewter, wood, or other inexpensive materials, and owning silver demonstrated your financial status. Making a silver coffeepot or teapot was complex; silver was melted at a temperature over 2,000 degrees, then poured into a mold producing a block of silver. The silversmith hammered the block into a sheet, and when the sheet was thin enough, the piece was hammered on anvils to start forming the cuplike shape, continually heating the metal and shaping and smoothing it. Any handles or legs for the pot were cast in sand and then soldered to the main piece, designs incised, and the whole pot polished. Originally, most of the silver was imported from England until the trade grew in the colonies. England passed laws that restricted the import of silver to finished pieces making it hard to find raw silver, and silversmiths had to rely on melting down old silver.

Paul Revere

Paul Revere (1735-1818) was born in Massachusetts and well-known as a patriot and political figure, also trained as a goldsmith, married twice, and had sixteen children. He worked with his father in gold and silver, a shop that stayed in the family for decades, engraved copperplates for printing, wrote multiple items, and did dentistry. His major political fame started when Revere was part of the Boston committee planning the tea revolt and the famous midnight ride. After the revolution, he worked with copper and the alloy pewter. The tankard (3.7.19) to hold drinks was a common item in Revere's shop, and the silver tankard had the typical domed top and a band around the middle. This tankard was overly large and monogrammed with SEB.

Myer Myers

Myer Myers (1723-1795), who lived in New York, became one of Colonial America's best-known and prolific silversmiths. New York had an ethnically diverse population; most people were Dutch, English, and African, with smaller numbers of Germans, Walloons, French, Scots and Irish. In addition to the established religions, minority groups included Huguenots, Quakers, Baptists, and Jews.[9] Although Jews were subject to discrimination, Myers had clients of multiple religions and political beliefs because of his versatility and skill. He also produced the first Jewish ceremonial objects in Colonial America, and some of his Torah bells are still used in synagogues today. The basket (3.7.20) is an example of Myers' excellent skills and ability to create detailed and complex silver pieces. During the Revolutionary War, he melted down metal items found in houses to make bullets for the soldiers.

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\): Paul Revere - Tankard (1795, silver, 26 x 21.9 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\): Myer Myers - Basket (1770-1776, silver, 28.4 x 36.7 x 28.9 cm) CC0 1.0

Cabinetmakers

In the colonies, the woodworker was an indispensable person making simple furniture, cradles, and coffins, the coopers made barrels, and the carpenters built the houses. Part of the construction relied on mortise and tenon joints made by joiners; however, as a wealthy class grew, the need for expensive and more decorative furniture developed, and the occupation of cabinetmaker became in demand. The cabinetmaker was experienced in the new method using dovetails to construct furniture. In the early colonies, furniture was influenced by the English styles, although more simplistic. As the cabinet makers became more experienced, French designs were followed with ornate legs, curved arms on chairs, or decorative feet. Walnut, oak, pine, and maple wood were plentiful and provided enough d without importing materials.

Charles-Honore Lannuier

Charles-Honore Lannuier (1779-1819) was born in France, and when he came to America, he promoted himself as the "French Cabinet Maker From Pari," using his French ideas of design. He made elaborately designed furniture with veneers and inlays, one of the preeminent cabinetmakers in high demand from the wealthier citizens. The trictrac table (3.7.21) of mahogany and rosewood was fashioned for writing or a card or backgammon table. The table had detailed veneer designs adorned with gilded brass and marble inlays.

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\): Charles-Honore Lannuier - Trictrac table (1810, mahogany, mahogany venner Rosewood, gilded brass, marble inlay) Public Domain

Duncan Phyfe

Duncan Phyfe (1768-1854) was born in Scotland and, after coming to America, became one of the most well-known cabinetmakers, influencing the entire marketplace. At first, he was recorded as a 'joiner' and later changed his designation to cabinetmaker gaining clients attracted to his exceptional design and quality. He created a style based on symmetry and balance in any furniture piece, a design that lasted for decades and is still known today. The top of the table (3.7.22) is hinged and sits on the heads of griffins in each corner. Carved out of rosewood and satinwood, the griffins were perfectly carved with detailed feathers and leg muscles; the tabletop placement seems to float lightly over the griffins.

As the colonies became a united country, populations expanded, and the economy's wealth grew, producing demand and support for the new American artistry; still, a mix of Europeans who migrated and native-born. The influence and requirements of the new country expanded the styles and types of art beyond the European standards with new ideas and concepts, blurring the lines of artistry, and opening art to the ordinary person.

[1] Lois S. Avigad (Fall 1987). Ruth Henshaw Bascom: A Youthful Viewpoint. The Clarion 12:41. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/american_folk_art_..._4_fall1987/40

[2] Laura R. Prieto (2001). At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America. Harvard University Press. p. 20. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=0b...page&q&f=false

[3] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artist/joshua-johnson-2479

[4] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/stua/hd_stua.htm

[5] 1772 Retrieved from http://br.mdsa.net/msa/mdstatehouse/pdf/wlt_final.pdf

[6] Retrieved from http://br.mdsa.net/msa/mdstatehouse/pdf/wlt_final.pdf

[7] Retrieved from https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.80.115

[8] Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h10.html

[9] Ellenor Alcorn, "Myer Myers: Jewish Silversmith in Colonial New York. David L. Barquist , Jon Butler , Jonathan D. Sarna ," Studies in the Decorative Arts 11, no. 2 (SPRING-SUMMER 2004): 112-114.