1.4: Kingdom of Benin (1180 CE – 1897 CE)

- Page ID

- 120725

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

In today's southern Nigeria, the Kingdom of Benin reached its artistic splendor from 1400 through 1600. The kingdom began in the 900s when the Edo people started building settlements. After continued warfare with others in the 1100s, they asked a neighboring king for help, and the king sent his son, who took command of the territory. By the 1400s, the new Oba (king) increased his army and began annexing additional lands, helping build a vast and wealthy kingdom. Benin traded along the western African coastline while ruling over the neighboring tribes. A series of earthen walls have been recently excavated and believed to stretch over 8,000 kilometers, perhaps to delineate territory. Because the houses were constructed of the local mud, the humid, wet weather has caused the walls to disintegrate and become part of the soil, making it impossible to discern the style and size.

The king's court was an immense area composed of palaces, homes for family and courtiers, and large gathering spaces. The kingdom had a strict social structure with the king and the highest priest, a semi-divine figure. The king ruled with input from a council usually composed of the many princely descendants with multiple wives. "According to Drapper, his harem consisted of nine hundred wives guarded by eunuchs."[1] All the land belonged to the king, and no other person could inherit property without the king's consent.

Artists were arranged into guilds for different types of materials or art under the direction of a master guild leader. The guilds were responsible for taking direction from the Oba for whatever requirements he needed. The 1400s became the Oba's Golden Age, the extended Benin City the center of a widespread kingdom. When the Portuguese came in the late 1400s, they found metropolitan areas, sizeable palaces, and homes all decorated with artworks made of ivory, bronze, brass, wood, and natural elements from animals and plants. When the British invaded in 1897, they destroyed the palaces and took most of the brass, ivory, and wooden artworks.

Initially, Benin crafted bronze by hammering and incising, then learned to cast bronze with the lost-wax method producing elaborate artwork. They used other materials also; however, because of the long-lasting quality of bronze, most of the surviving artifacts were made of bronze. During this period, the communities were surrounded by walls and ditches, and an Oba ruled each clan. The Oba or a designate could only commission the works of bronze, and the bronze artwork was kept in the palace. Each Oba maintained their own guild of artisans who were masters of their trade. The objects were created to exalt the king, his household, armies, and others of elite status and used in ceremonial events. When an Oba took his position, he had to create an altar to honor his father and his mother if she was a queen, these pieces of art were made for use on the altar. Other artwork was created for agricultural festivals, spiritual activities, or ceremonial events.

Although artifacts were made of bronze, many were created from brass, similar materials using the same procedure for construction. Bronze is mainly made from copper with the addition of tin and small amounts of other minerals. Bronze was the original material used by artists since 3500 BCE. Brass was also made with copper and mixed with zinc instead of tin with other trace elements as required. The melting point for brass is lower than bronze and is somewhat more malleable. It is unknown when Benin started casting brass; however, it was a highly respected talent, and the kings supported a guild for brass casting. Using the lost-wax method, they made exceptionally detailed models, then covered the model with clay. When heated, the wax melted out of a channel, and the liquid metal was poured in to set. The clay was broken away after the metal hardened.

The first obligation of the new king was to create a shrine, dedicated to his predecessor and serving as the site at which the living monarch communicated with his ancestor or father. Ensuring dynastic continuity, the shrine held various carved and cast artifacts, including freestanding brass heads... The head acted as a vessel through which the late king transferred his power to the new king, the latter accepting the responsibility for successfully directing and defining his life. The Edo people considered the head to be the locus of a man's character, knowledge, authority, success, and family leadership. These sculptural heads were a consistent visual point of reference from ruler to ruler, reinforcing the idea of familial succession across a single dynasty. The Oba is often called by his praise name "Great Head," emphasizing the head of the living leader as the center of responsibility for the kingdom.[2]

Heads

The bronze or brass heads sat on ancestral altars and were not based on the exact facial characteristics of the departed but rather on a stylistic, natural look. Some metalheads had an opening in the top to hold an elephant tusk engraved with decorative images. "The metal pieces were made using lost-wax casting and are considered among the best sculptures made using this technique.[3]

The cast bronze head (1.4.1) portrayed an idealized likeness, generally made to look like the Oba when he was young. The woven cap on his head is patterned after coral beads with a single bead hanging down on his forehead, a tribute to the artist who created the perfect symmetry and detailed cap. Coral was imported, a valuable commodity for the Oba. His face reflects the perfect youth in a natural, undistorted image. The head would be placed on the altar made to honor the king.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Head of an Oba (16th century, brass, 23.5 x 21.9 x 22.9 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Head of an Oba (16th century, brass, 23.5 x 21.9 x 22.9 cm) Public Domain

The Head of Oba (1.4.2) has more elaborate ornamentation. The cap is made to look like coral beads strung together with larger beads on the cap and three small beads over each eye, and one in the middle. The face is perfectly rendered, and his neck is encased with eighteen layers of beads encircling his neck—long strands of coral hang from the cap around both of his ears.

Historians believe earlier altar heads were made from terracotta, and later brass became more prestigious. The terracotta head (1.4.3) appears less refined, with fuller features in the wider nose, bigger eyes, and an uneven beaded cap. Some historians believe the terracotta heads may have been used to store the coral or original designs used as models.

Plaques

During the sixteenth century, the artisans of the Benin art guilds made a series of brass plaques to line the front of the palace. A later European visitor wrote about the extensive palace complex with multiple courtyards, huge rooms, and even galleries with pillars covered by the plaques. Historians believe the plaques were arranged in a specific order with some relationship or narrative occurring. There was an established convention of the most significant person appearing as the most prominent figure. The plaque with the Oba and his warriors (1.4.4) depicts the Oba as the most significant and dimensional figure ensuring his status while his small attendants are behind him. The king wears a studded helmet and carries an elaborate sword.

TheIyase (1.4.5) was the chief and chosen by the Oba for his qualities. The Iyase acted as second in command to the Oba and was in charge of the army. He wears an elaborate headdress and carries the sword of authority while attended by the lesser person, a very low-level person based on the size of the figure.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Iyase with Sword and Attendant (1550-1680, brass, 40.6 x 18.4 x 6.4 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Iyase with Sword and Attendant (1550-1680, brass, 40.6 x 18.4 x 6.4 cm) Public Domain

Mounted on a horse, the Oba (1.4.6) and his attendants ride under the salute of swords by his warriors. The warriors are almost the size of the king, a portrayal of their essential status, while the attendants are small, with very unimportant positions. The junior court official (1.4.6) does not have any attendants, wears simple clothing and a helmet, and carries a small sword, demonstrating his position as a lower-level warrior. The artists making the plaques frequently added other decorations on the plaque to fill in empty spaces or perhaps leave their mark. They also added holes on the plaques for the nails to hold them on the pillars.) and his attendants ride under the salute of swords by his warriors. The warriors are almost the size of the king, a portrayal of their essential status, while the attendants are small, with very unimportant positions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Equestrian Oba and Attendants (1550-1680, Brass, 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Equestrian Oba and Attendants (1550-1680, Brass, 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm) Public DomainThe junior court official (1.4.6) does not have any attendants, wears simple clothing and a helmet, and carries a small sword, demonstrating his position as a lower-level warrior. The artists making the plaques frequently added other decorations on the plaque to fill in empty spaces or perhaps leave their mark. They also added holes on the plaques for the nails to hold them on the pillars.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Junior Court Official with Sword, (1550-1680, brass) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Junior Court Official with Sword, (1550-1680, brass) Public Domain

Masks

Multiple rituals and ceremonies were essential to Benin's life, a way to cleanse the kingdom of past problems and for the king to ensure his power. During the ceremonies, royalty, and those of elite status, wore elaborate works of art made of brass or ivory, ornamental textiles, or layers of coral beads. The mask in the shape of the leopard's head (1.4.8) was part of the display and was worn around the waist. The leopard was an important animal, a symbol of strength, and tamed leopards were often found in the palaces, showing the power of the king to control a wild animal. In a procession, the Oba might be preceded by leopards on long chains indicating his strength. Images of women were rare and generally represented a female who was a queen or the mother of a king.

The ivory mask (1.4.9) would be reserved for special ceremonies and usually worn by the king to honor his mother; the ivory represents purity. The facial features on the mask are distinct, with bands of metal inlaid on the forehead, and carvings of mudfish are part of the collar below her chin and the tiara. Mudfish lived in water but could survive on land, thus representing the king as both divine and human.

The brass mask of a face (1.4.10) was made in the king's image and hung from the necks of his high-level chiefs and elites to demonstrate loyalty for the king. As in the style of many masks, the chin is framed with loops to hang rattles. The eyes are intense, an image of his power as a ruler while his nose and mouth appear sensitive, the look of a thoughtful king.

Sculptures

Only the Oba could commission works of art in bronze. The sculptures were small and used for ceremonies, each one made with detailed precision. The horn player (1.4.11) represented a court musician and was made for one of the king's shrines. The figure is wearing an elaborately detailed leopard hide with coral beads around his neck. The horn was blown from the side and the artist making the statue demonstrates Benin's expertise in lost-wax casting.

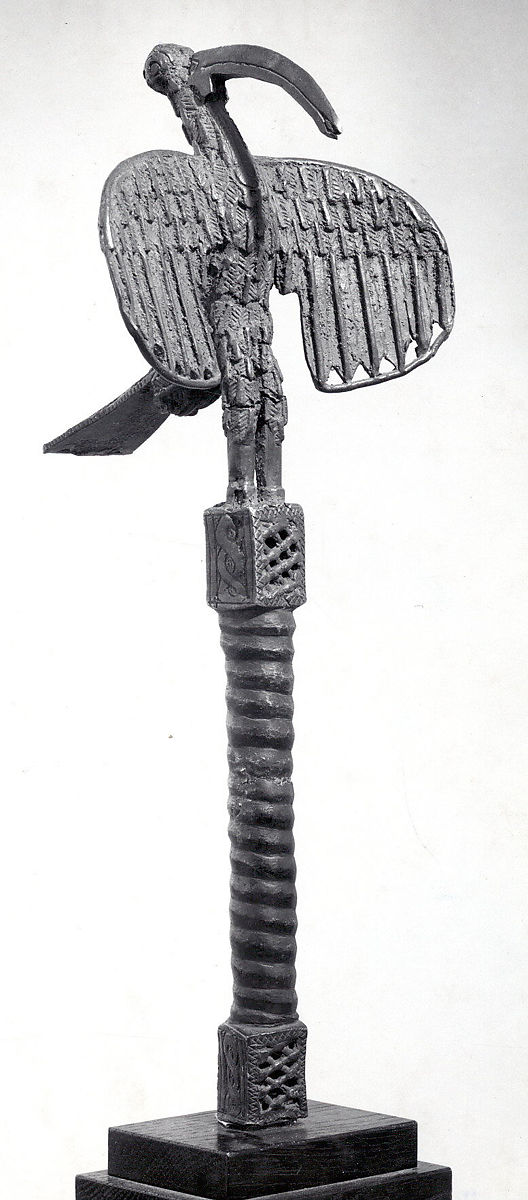

The bird of prophecy (1.4.12) has extended wings and an oversized beak and was a percussion idiophone carried by the chiefs and struck on the beak with a rod. The birds, along with plaques, decorated the palace. Large metal birds were often installed on the roof of the palaces demonstrating the Oba is the overseer of the people.

The ivory gong (1.4.13) was finely carved with an additional small cup in the front. Officials carried the gongs during rituals, tapping them to create sounds to dispel evil spirits.

The arts of Benin had a long tradition of creative and innovative art promoted by the rulers who used art to define their history. Benin art started in the late 13th century and developed a longstanding portfolio of artwork. The altars and artwork in the palace complexes remained in place and were used over the centuries by Oba rulers. Unfortunately, in the 19th century, the British invaded Benin to conquer the people and destroy their culture. Before they burned the town, they confiscated the artwork, taking most of it and selling it worldwide. The British did not document the Benin artwork, losing an entire history of the civilization.

[1] Carré, L. (1936). Benin -- The City of Bronzes. Parnassus, 8(1), 13-15. doi:10.2307/771199

[2] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/312290?searchField=All&sortBy=relevance&ft=kingdom+of+benin&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=12.

[3] Nevadomsky, J., African Arts, Art and Science in Benin Bronzes, Spring 2004, 37(1), p.95-96.