1.5: Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE)

- Page ID

- 120726

Introduction

The Ming Dynasty was a time of growth, the population doubling supported by an extensive trade increase with the rest of the known world. Zhu Yuanzhang, who became Emperor Hongwu, lived as a beggar in a Buddhist monastery until local uprisings inspired him to join one of the military organizations. He quickly rose through the military ranks, leading the forces to drive the Mongols out of China and establishing the Ming dynasty. Although he used draconian methods, Emperor Hongwu reformed the government and purged the military of those high-ranking generals he considered corrupt, seized large estates, and forbid and Mongol customs, even changing the people's clothing from the Mongol style to a different fashion. One of Zhu Yuanzhang's significant achievements was developing the Yellow Register Archives, a monumental population survey, the largest in the world before modern times. He originally wanted the survey for tax purposes; however, it reached beyond the limits of taxation to create a long-lasting record of the people of China.

In the 15th century, during the Ming dynasty, the population was 85 million. Professor Craig Clunas from Oxford wrote: "It had a greater land area, bigger cities (and more big cities), bigger armies, bigger ships, bigger palaces, bigger bells, more literate people, more religious professionals."[1]

Ruling and maintaining peace was complex; the Mongols continually fought along the borders, adherence to new regulations was difficult to enforce, and the massive numbers of peasants to be employed and fed presented challenges. Zhu used his family and sons to help consolidate his reign and prevent ministers' or regional leaders' ability to develop any rebellions creating a return to the feudalistic concept of relational fiefdom control. Constantly worried about uprisings, Zhu even established rules for his family based on Confucianism rules of ideals and values, although the sons had leeway within their local domain. One son, Prince of Yan, lived in the current city of Beijing and declared his authority and procedures, built an extensive network of contacts and support and grew in power.

When Emperor Hongwu died, his documented succession of inheritance began to crumble, bringing successive court intrigues and battles among the potential heirs. The Prince of Yan had continued to extend his power, slandering others and spreading lies to legitimize his position as rightful heir, leading to civil war. After a lengthy set of conflicts and the slaughter of thousands of people, the Prince of Yan finally captured the capital at Nanjing, naming himself Emperor Yongle (Everlasting Happiness) and moving the capital to Beijing. As emperor, he needed to ensure the strength of his position and "undertook two enormous projects…the compilation of an authoritative 11,095 volume encyclopedia of Chinese learning and the construction of the Imperial Palace in Beijing over the ruins of Khubilai Kahn's capital."[2]

Forbidden City

Starting with the Ming Dynasty, the Forbidden City (1.5.1), constructed between 1406 and 1429 in Beijing, was the home for the emperors and the governmental center for almost 500 years. The city was extensive and contained over 950 buildings, a style now considered traditional architecture for Chinese buildings. The complex was made with wood and designed around a central axis and symmetrical design; the front outer court and the rear inner court.

…more than a million precious royal collections, articles used by the royal family and a large number of archival materials on ancient engineering techniques, including written records, drawings and models, are evidence of the court culture and law and regulations of the Ming and Qing dynasties.[3]

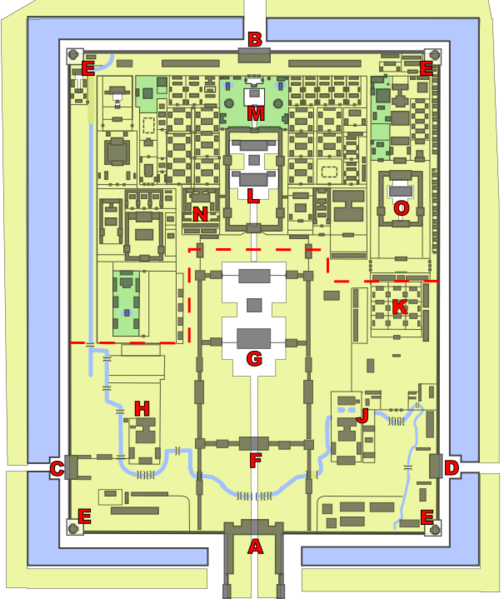

On the Plan of the Forbidden City (1.5.2), the Meridian Gate (A) is the main entrance to the city from the outside, the Gate of Divine Might (B) the back entrance, with (C) and (D) as side entrances and guard towers located in each corner (E). The Gate of Supreme Harmony (F) forms the gateway to the inner court in the inner courtyard. The Hall of Supreme Harmony (G) is located in the center of the plan, the focal point from the entrance. The front part of the city contains the Hall of Military Eminence (H) and the Hall of Literary Glory (K). In the back half of the city is the Palace of Heavenly Purity (L), the Hall of Mental Cultivation (N), and the Palace of Tranquil Longevity (O), as well as the central imperial garden (M).

The construction of the complex covered fourteen years and was assembled with logs from the unique Phoebe Zhennan trees moved by the river over four years and marble quarried from nearby hills, which could only be carried by sled when the ground was frozen. Special bricks, which resembled gold blocks, were made for the floor. Over time, construction used almost one million people (most conscripted) and about 100,000 artisans and craftsmen. The walled Forbidden City was enclosed within the walled Imperial City and surrounded by the Inner City. The Forbidden City was designed on a north-south axis with the southern exit leading to Tiananmen Square, today's center of Beijing. The city was divided into two parts, the outer courtyard was used during ceremonies, and the inner court area held the residential and governmental buildings. The design was based on traditional practices; orientation to the cardinal directions, the residences in the center of the complex, and axial walkways. The Forbidden City wall was 7.9 meters high and made of rammed earth covered with bricks and mortar. Each side of the wall had a gate; the Meridian Gate (1.5.3) was located on the southern end and had projecting wings forming a large central entrance and square.

The stone path led from the gate through the city, starting the Imperial Way, the walkway for the emperor. Gate of the Divine Might (1.5.4) was the opening for the northern side of the wall. All of the gates were decorated with doors embedded with golden nails.

Towers (1.5.5) are located at all four corners, each made with intricate roofs and ridges (1.5.6). The towers were the parts of the city seen by the ordinary people who inhabited the areas outside the walls. No trees were planted outside the Imperial Garden, allowing people to take long walks toward a gate with time for meditation.

Towers (1.5.5) are located at all four corners, each made with intricate roofs and ridges (1.5.6). The towers were the parts of the city seen by the ordinary people who inhabited the areas outside the walls. No trees were planted outside the Imperial Garden, allowing people to take long walks toward a gate with time for meditation.

_-_China-6164.jpg?revision=1)

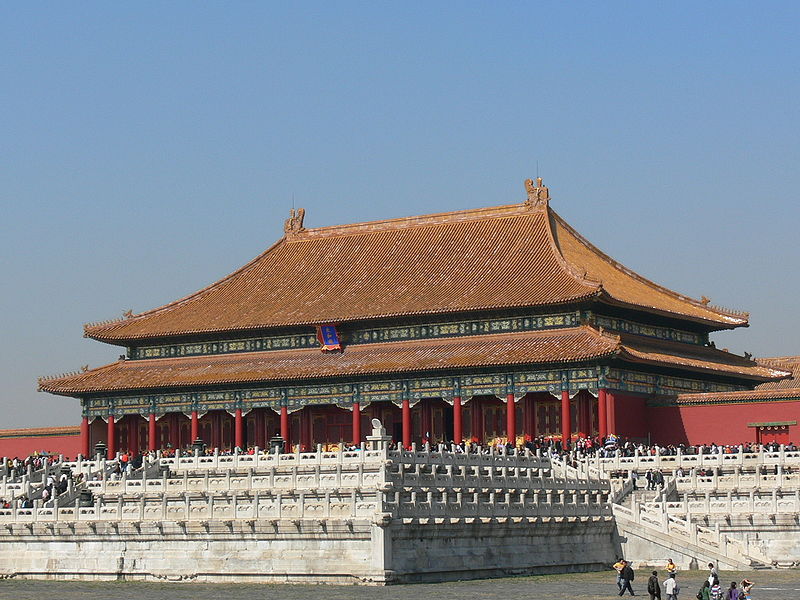

After entering the Meridian Gate, the large courtyard had a stream to cross and traverse through the Gate of Supreme Harmony, entering into the inner areas, the location of the major buildings. One of the prominent structures is the Hall of Supreme Harmony (1.5.7), located in the central part of the complex. The hall was constructed thirty meters above the square as the center of power, imperial decrees, weddings, and ceremonies. The roof has a double-eave hipped roof demonstrating the command of the emperor. Other buildings might have a single eave or gable roof for those of lesser importance.

Inside the hall (1.5.8) stands the spacious throne room with six pillars, all encased in gold—a dragon motif in an elongated shape and powerful head, the entire area. The legendary creature is symbolic of the auspicious powers of the emperors. The sandalwood throne also had ornate dragons coiled around.

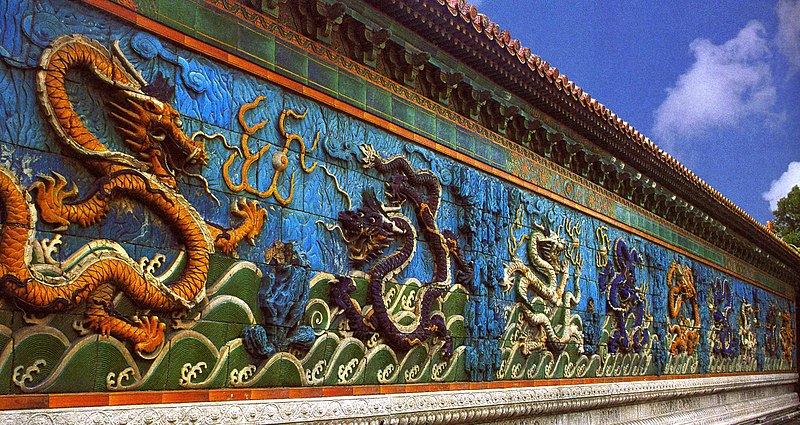

The Palace of Tranquil Longevity was developed by an emperor awaiting retirement and wanted to live in luxury. He designed a smaller complex with inner and outer courts, temples, and lush gardens. The entrance to the palace is faced with the Nine Dragons Screen, a standard wall structure for privacy. The wall made of tiles fit together like a puzzle (1.5.9), each with different designs and raised and textured parts.

Because multiple artists created the wall, the overall pattern was defined and sectioned, formed in an elongated shape with a powerful head (1.5.10). Each artist worked with clay and colors to create a broad set of dragons.

Design, color, and symbolism were essential elements in the construction of the Forbidden City, all based on the concepts of religion and philosophy. Color had specific meanings; yellow was the most symbolic color of the earth and holder of life, therefore the color for the emperor. Most of the roofs, the highest part of the building, had glazed yellow tiles.

The auspicious color red, which the Chinese associate with power, happiness, wealth, and honor, is ubiquitous in the Forbidden City. High walls were washed with red clay from Shandon Province, which was also used to fix roofing tiles in place, and red can be seen predominantly on gates, doors, window frames, exterior timbers, and interior columns. Such was the Ming's fondness for red that all reports to the emperor had to be written on red paper, while later Qing rulers insisted that any written orders from the emperor were to be recorded in red ink. The intricately decorated interior timbers, pillars, and crossbeams (1.x) often set red against yellow or gold, with elaborate dragon motifs and commonly used Buddhist symbols. Gold leaf from Suzhou was often applied for finer decorations on pillars and gables.[4]

Dragons represented the emperor and his omnipotence; the lotus flower symbolized harmony, and the duck or heron might mean long life. The gates were guarded by stone or bronze lions. Throne rooms (1.5.11 and 1.5.12) were covered with red and gold, numerous dragons in lavish displays represented the emperor, all designed in an axial pattern.

.jpg?revision=1)

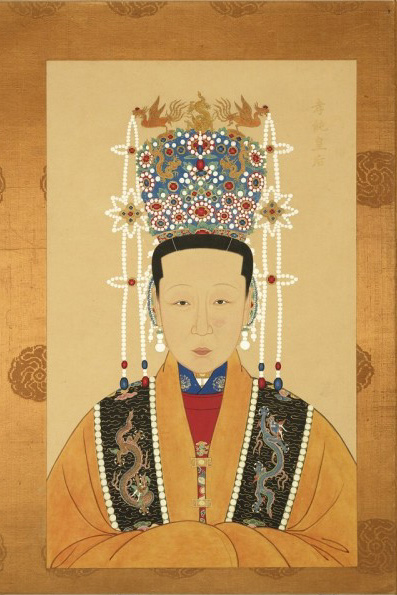

The headdresses worn by royalty played an important role, especially for women. Fengguan was known as the phoenix crown and was highly embellished with kingfisher feathers (a rare bird during this time), gold dragons, beaded birds, gemstones of rubies, or sapphires and pearls. The type and designation of rank determined how many decorative elements were in the crown; the empress or crown princesses wore the most elaborate crowns. The style dictated how many gold dragons were allowed or how many ornaments might hang down on the sides. The pearls, feathers, and gemstones were fashioned into flowers, leaves, or other symbolic ornaments. The crown worn by Empress Xiaochun (1.5.13) had multiple dragons and elegant beaded blades hanging down from the very tall crown, indicating her rank.

The beautiful turquoise crown (1.5.14) is similar to the one in the painting of the empress with oversized golden dragons and pearl blades on the sides.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): Queen's headdress (Blue tian-tsui leaves and birds, gold dragons, pearls, polished semi-precious stones) CC BY-SA 1.0

The Four Masters of the Ming Dynasty

The Ming Dynasty brought prosperity to the region and significant achievements in artistic pursuits. Painting became an important art form based on previous styles with more colors, especially seal brown, a color similar to the fur on seals. Because of the popularity of painting, many new schools were formed, developing contemporary master painters. Four prominent painters dominated the era, Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, Tang Yin, and Qiu Ying, who were considered the masters of the dynasty. Qiu Ying painted in the style of the court artists Shen Zhou and Wen Zhengming following a type defined as literati – an interest in personal intelligence, scholarship, and expression. They didn't paint nature realistically; instead, they expressed their thoughts, ideas, and feelings in the painting. Tang Yin adopted a style in the middle of the others. They all attended and taught at the Wu School, a place for professional artists to gather, paint and sell their paintings and for new artists to learn. They studied and were experts in the "Three Perfections"; painting, calligraphy, and poetry, the artistic standard of the time.

Shen Zhou

Shen Zhou (1427 – 1509) was from a wealthy family and spent his life painting, writing poetry, and calligraphy; and was considered one of the elite painters. He founded the Wu School, bringing new ideas based on historical traditions and a more intimate style with trees, rocks, and calligraphy conventions. He was known for his landscapes, flower and bird paintings. In Poetic Feeling of Fallen Flowers (1.5.15), the small image of man is a focal point yet seemingly overwhelmed by nature's structures: looming mountains, broad river, and the trail through the trees and hills. Strong brushstrokes are evident in the trees and bushes, painted with ink and color on paper. The background is very delicately painted.

Reading in Autumn Scenery (1.5.16) has bold brushstrokes throughout most of the painting; only the small, thoughtful man is judiciously added to the image. Shen Zhou frequently added calligraphy to balance the image and provide meaning to his ideas.

Wen Zhengming

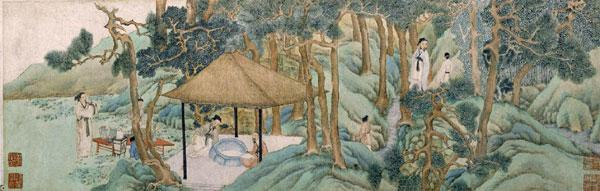

Wen Zhengming (1470 – 1559) spent several years pursuing a career in the government only to fail the civil examinations nine times and finally decided to abandon his ideas and turn to paint, calligraphy, and poetry. He studied under Shen Zhou, examined the ancient painters, and developed his style using ink and color in various dark and light tones. In many paintings, he favored washes colored blue and green. Huishan Tea Party Map (1.5.17) demonstrates the multiple tones of blue and green he used to form the background with detailed brushstrokes, heavy at times and delicate at others.

In calligraphy, Wen Zhengming studied a wide range of artworks from the past. An exceptionally diligent student, he himself said that practicing calligraphy was one of his daily activities upon waking up every morning, never tiring of it throughout his life. Wen came to excel at the major calligraphic types, with small regular and running scripts most reflecting his personal style. His small regular script is sharp and orderly, and even at the age of ninety he could still do tiny "gnat's-head" writing. Wen's running script is also elegant yet vigorous, with most of such surviving works tending towards semi-cursiveness.[5]

In one of his albums, Wen Zhengming painted small landscapes (1.5.18) with ink on paper using bold strokes for the trees and mountain tops and delicate lines to represent the buildings.

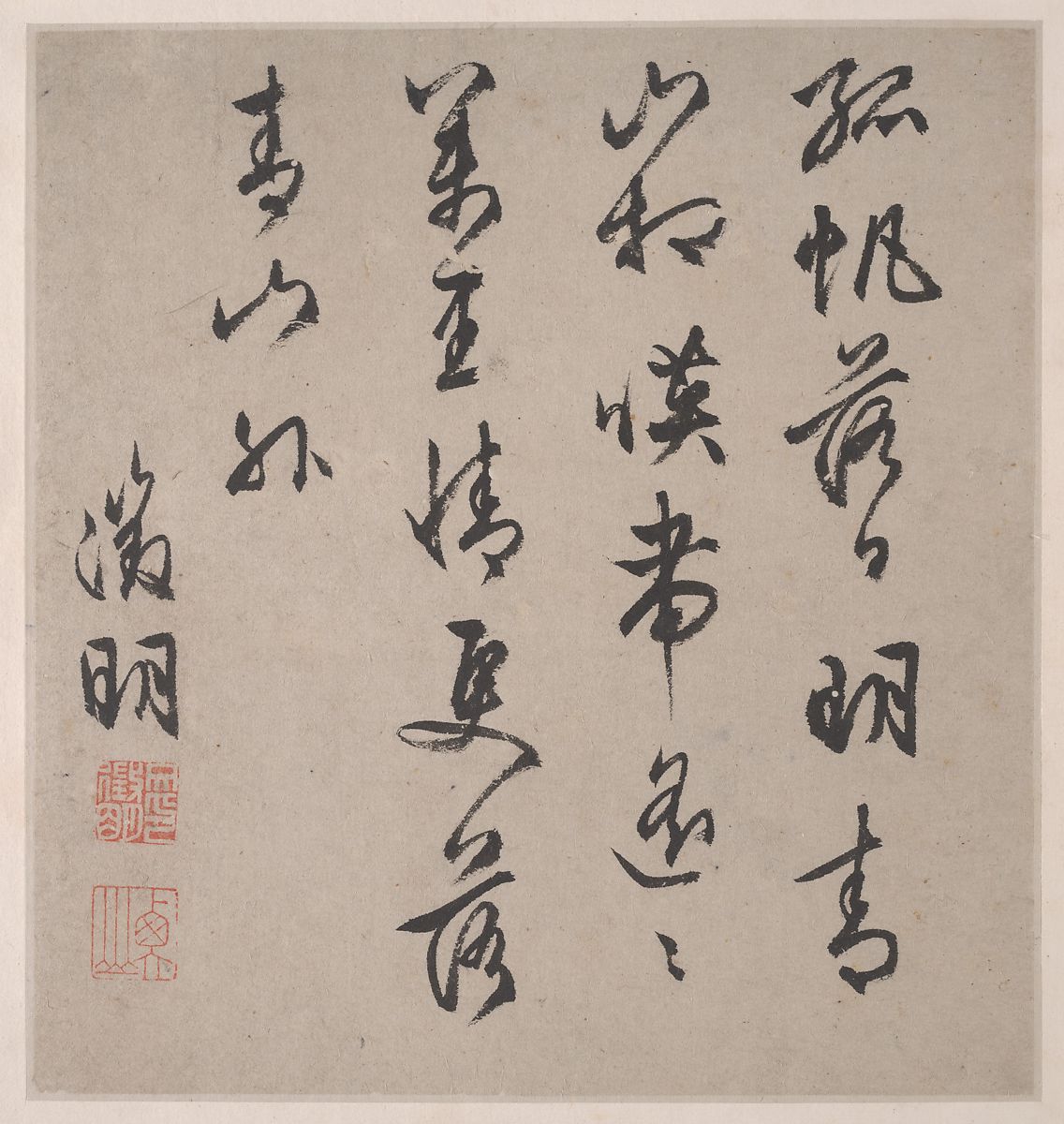

He faced each painted image with a poem (1.5.19), demonstrating his skills in calligraphy. As one of the four masters, he had many students that adopted his style, including his sons, and he was known with Shen Zhou as one of the leaders of the Wu School.

Qui Ying

Qui Ying (1494 – 1552) was a painter from an early age, exceptionally skilled in copying the old masters. As he grew older, he focused on figures and flowers, usually set in landscapes. He was known for his figures created with very fine lines in ink. The images in the painting Pavilions in the Mountains of the Immortals (1.5.20) demonstrate his use of lines to create the detail in the work, particularly as he gave life to the mountains.

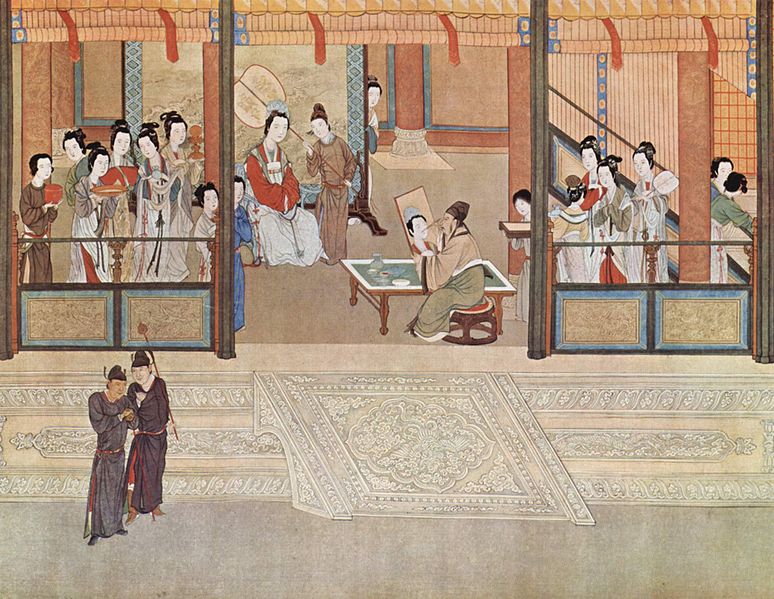

Spring Morning in the Han Palace (1.5.21) is part of a long scroll with multiple scenes of life and activities in the ancient palace. Qui Ying's skill with brushwork and fine detailed lines is reflected in every aspect of the painting, from the intricate flooring to the details on each figure.

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\): Spring Morning in the Han Dynasty (Ming Dynasty, ink and colors on silk, 30.6 x 574.1 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\): Spring Morning in the Han Dynasty (Ming Dynasty, ink and colors on silk, 30.6 x 574.1 cm) Public Domain

Tang Yin

Tang Yin (1470 – 1524) was one of the most famous of the Four Masters painters who, like the others, was accomplished as a painter, poet, and calligrapher. Early in his life, he pursued a job in the civil service where he was accused of bribing an examiner and deprived of any further service in the government, freeing him to pursue an art career. Many of his paintings focused on the activities and beauty of women and the interaction of people. Tao Gu Presenting a Lyric (1.5.22), painted on silk, portrays Tao Gu sitting on a bed with his writing materials, ready to create a poem. The woman is playing a pipa while the small figure on the bottom left seems to be hiding. Each person wears a blue robe, setting the people out from the overall color palette of the background. Tang Yin wrote a poem, written in calligraphy on the top right side, probably based on Tao Gu's poetry.

Court Ladies in the Shu Palace (1.5.23) demonstrated the detailed brushwork of Tang Yin. Each of the ladies wore elaborate headdresses and gowns. He used a few spots of red to emphasize space as the blue gown in the middle centers the painting.

Ming Porcelain

During the Ming Dynasty, porcelain production was consolidated in Jingdezhen, manufacturing imperial goods for the court and export. The fine white clay in the region produced a translucent quality, able to be fired at very high temperatures and produce exceptionally thin, smooth pottery. It became so important and exquisitely fashioned; the emperor had his line complete with the royal mark. The royal kilns produced the well-known Xuande style, usually in the blue and white porcelain favored by the emperor.

The Chenghua variety featured contending colors over the blue and white and overglaze outlined and filled decorations of bright reds, pine greens, or sunburst yellows. Wanli porcelain was ornately patterned and painted with five colors, generally red, black, yellow, green, and purple. Dehua ware became known as 'Blanc de Chine' or white china and had such a pure white color it was frequently used to make Buddhist or religious statues. Many large production kilns were constructed to satisfy the perfected porcelain, a significant export of Islamic and European trade routes.

The ceramic material was made from kaolin clay, porcelain stone, or a mixture of both, which produced the fine white ceramic. It was usually fired by oxidizing the conditions during firing when the amount of oxygen was controlled. Improved clay combinations allowed them to make thinner vessels in a wide range of shapes and new glazes gave the ceramics a whiter, shinier look. The requirements from the Islamic world influenced the designs of the porcelain, and they imported cobalt blue from Iran, the typical color used on many vessels. The perfection and beauty of the Ming porcelains were in great demand, and in 1433, the imperial kilns had an order for 443,500 pieces of porcelain with the unique dragon and phoenix design.[6]

The large porcelain jar (1.5.24) made in Jiajing period has a lid painted in a pond with carp and aquatic plants with a nob on top to lift it off. The underglaze was painted with repeated designs of brown carp, water weeds and lotus flowers in blues and greens.

.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\): Wine Jar with carp among water weeds and lotus, Public Domain

The porcelain vase (1.5.25) has the unusual shape of a double gourd. Small flowers surround the middle with scrolled lotus leaves and flowers created by an underglaze of blue. The repetitive design and shape of the vessel resemble Islamic designs; perhaps this was a vase made for export to one of the Islamic countries.

_with_the_Eight_Immortals_(Baxian)_LACMA_53.41.6a.jpg?revision=1) Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\): Jar with the Eight Immortals, Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\): Jar with the Eight Immortals, Public DomainThe porcelain bowl (1.5.26) was covered in dark blue with a design in raised slip and enamels of light blue and yellow flowers, a departure from the standard design.

Although white and blue were the most common colors, other porcelains were made for domestic use and exports. The bright orange bowl (1.5.27) was incised with the green dragon, secondary, complementary colors, using the typical dragon design in an unusual color combination.

The porcelain ewer (1.5.28) was painted with enamels and gilded, the bright red forming the base color with gold and turquoise used as the overall accenting designs of complementary colors. The pear shape and long, thin handle and spout made this ewer very unusual.

In later centuries, the art of the Ming dynasty was considered flamboyant and affected by too many ideas from other places. However, further evaluation led many to believe Ming art had "boldness and originality, perfection of craftsmanship and whimsicality, above all with a strength and splendor comparable only to the strength and splendor of the baroque art of Versailles."[7]

[1] Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/16/arts/international/ming-the-dynasty-behind-the-vases.html

[2] O’Riley, M. K., (2002). Art Beyond the West, Prentice Hall, p. 133.

[3] Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang, retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/439,

[4] Gao, J., Education About Asia, Symbolism in the Forbidden City, 21(3), Winter 2016. Retrieved from http://aas2.asian-studies.org/EAA/EAA-Archives/21/3/1438.pdf.

[5] China Online Museum, Wen Zhengming, retrieved from http://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/wen-zhengming/. .

[6] Morris, R. C., (16 October 2014). New York Times, Ming: The Dynasty Behind the Vases. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/16/arts/international/ming-the-dynasty-behind-the-vases.html.

[7] Grigaut, P. (1952). Art of The Ming Dynasty. Archaeology,5(1), 11-13. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41663027