1.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 120722

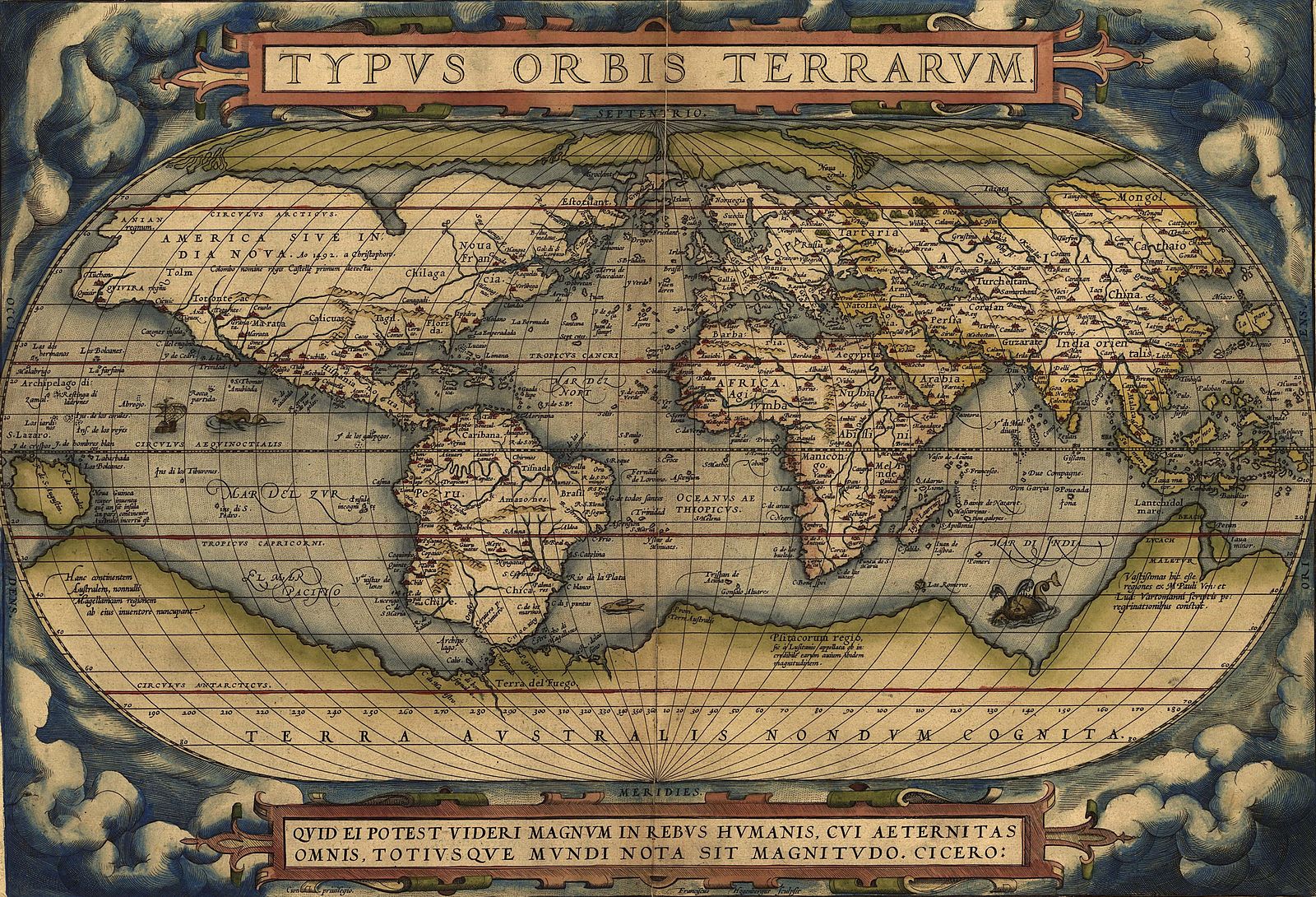

Figure 1.1.1 Typus Orbis Terrarum ORTELIUS, Public Domain

Figure 1.1.1 Typus Orbis Terrarum ORTELIUS, Public Domain

Western Europe

Western Europe entered the 'Age of Discovery' during the 15th to 17th centuries, a time of exploration across the oceans and intrusive colonization in other geographic areas. The Typus Orbis Terrarum (1.1.1) came from the first modern atlas (Theatrum Orbis Terrarum) made in the Netherlands as a compilation of multiple cartographers. Over fifty maps were printed using copper plates, so they looked similar and were arranged by different continents and areas. Although he did not use an accurate scale for each region, Abraham Ortelius combined the maps into one image. Europeans located Australia; however, the extra-large size for Terra Australis was based on the concept of the Southern Hemisphere (they knew nothing about it), and it must be the same size as the Northern Hemisphere. They created an equalized land.

Europeans traded with Asians along the Silk Road for an extended period of time. Transporting goods along the routes was expensive and slow as significant routes were controlled by Muslim middlemen who extorted taxes, fees, and transport costs. The Crusades and conflicts with Muslims made the routes more difficult and expensive. Europeans needed to find other routes to bring the exotic spices, silk, porcelain, and other imports, investing money to send ships off to explore. Another motivation was the dominance of religion and the concept of bringing Christianity to the world. "Historians generally recognize three motives for European exploration. Particularly in the strongly Catholic nations of Spain and Portugal, religious zeal motivated the rulers to make converts and retake the land from the Muslims."[1]

Figure 1.1.2 European ap Circa 1600, Public Domain

Figure 1.1.2 European ap Circa 1600, Public Domain

The Portuguese started in early 1400, sailing along the African coast, finding a new route to India by sea and across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas. England, Spain, and France quickly sent expeditions exploring other known and unknown parts of the world, coming in contact with new cultures and encountering unfamiliar populations of people, animals, and plants. The initial naval explorations soon led to invasions and military conquests, the spread of diseases, the exploitation of local populations, and the increase of the Christian religion. During this period, global trading increased, no longer limited to land travel or regional seas, bringing significant economic growth to European countries.

The expansion of new territories and markets allowed a wealthy merchant class to progress in the European countries as the primary monetary centers moved from the Mediterranean regions to Europe. In the Netherlands, Antwerp and Amsterdam became the wealthiest cities, leading to the Dutch Golden Age, as exotic goods and spices brought by the Portuguese shippers passed through the towns. The Portuguese sent traders to China, establishing contacts with the Ming Dynasty for silk and porcelain. Europe's economic structures were structured on gold or silver, and Spain extracted large amounts of the metals from Mesoamerica, a source of significant fortune for Spain. No longer was wealth only existing in the realm of the ruling class; ownership and availability of money also became a part of the burgeoning middle class.

Art in Europe expanded, and private citizens paid artists to paint, sculpt, and weave. Artists no longer worked as individual craftspeople in large workshops, and some artists gained fame in their lifetime or recognition by later discoveries. The Protestant Reformation in the Netherlands and Germany changed the ideals of spiritual paintings still found in Italy or Spain. Art was no longer based only on religious concepts; people wanted portraits of themselves or other interesting images.

Western Africa

Western Africa developed into multiple kingdoms (1.1.3), each with its city-state territories. In ancient Ghana, the kings inherited rule through the mother, a matrilineal society, as opposed to the kings in Europe who were patrilineal. The kings were powerful and controlled the wealth, much like the European kings. One of their major products was gold, and as rulers extended their territories, they captured many of the gold-producing regions. Muslims from the north used caravans to trade with the kings and described the splendor of the court, the gold ornamentation, and delicate fabrics.

The Mali Empire also traded with those from the north and converted to Islam, although its different kings still maintained control of their subjects. The empire grew affluent from the viable trade industry and built major cities with elaborate mosques and libraries. The constant succession problems of the actual legitimate king started to weaken the empire, leaving it open to warfare and control by others. Arising from parts of the Mali Empire, the Songhai Empire exceeded the size of Western Europe. The king established provinces that governors controlled, helping build the vast trade routes. By the mid-1400s, the Benin Empire expanded, their kings expanding their territory and building unique cities. Some parts of the region were still inhabited by small villages with autonomous controls and cultures.

_detailed.jpg?revision=1) Figure 1.1.3 African Map circa 1606, Public Domain

Figure 1.1.3 African Map circa 1606, Public Domain

In the 15th century, the Portuguese wanted a new oceanic route to Asia. They first came to Western Africa, hoping to interrupt the trans-Saharan trade routes for gold used by the Muslims in North Africa and bring the gold to the Christian governments of Europe. The Portuguese quickly recognized the vast extent of the gold mines and trade in the region, setting up outposts in several locations. The rulers of African areas wanted imports brought in and the Portuguese expanded trade, opening the possible routes for other European countries.

Art in Western Africa was generally driven by the desires of regal authority based on specialized requirements. The artists did not have individual status and worked in guilds led by a master. Artists predominately used natural resources of wood, ivory, animal skins, and metals to produce pottery, figurines, jewelry, ceremonial adornment, and architectural embellishment. Survival of artwork was difficult; the humid climate naturally decomposed materials, buildings made of mud blocks also disintegrated, and European invaders removed much of the artwork to take back to Europe and sell.

Asia

Asia In the 1400s, the Ming Dynasty (1.1.4) was economically dominant, supporting huge populations, and developing prosperous manufacturing centers and agricultural lands. The Chinese developed excellent irrigation systems, built canals to transport goods and produced fine silk and exquisite porcelains. They also developed an extensive landlord class who methodically started to claim peasants' land, forcing them to become tenants. China changed from an agrarian economy to a well-developed competitive commercial economy during the Ming dynasty, trading with other Asian countries and across the Silk Road. However, China did not invest in sea power or trade across the oceans, leaving them completely unguarded when the European ships incursions into coastal cities.

Because the Chinese economy was so robust, and the trade they developed earlier placed them in a better economic position than the Europeans, the emperor saw no reason to import European goods or move to maritime trade. China controlled the spice and tea market as well as porcelains, silk, and cotton. However, in the late 1500s, China moved to silver as their monetary base, so they had to import a scarce metal in China. The Europeans had established trade routes with countries in Mesoamerica, giving Europeans a more favorable trade position as they brought silver to pay for their Chinese goods. The Europeans also brought new foods to the Chinese from Mesoamerica, including sweet potatoes and peanuts, foods the Chinese could grow quickly and help feed its expanding population. The Portuguese, Spanish, and English became competitive, establishing lucrative trade routes, developing their economies, and ensuring continued access to Asia.

.jpg?revision=1) Figure 1.1.4 Asian Map circa 1606, Public Domain

Figure 1.1.4 Asian Map circa 1606, Public Domain

Art in China became a focus for the Ming dynasty as the court established the parameters of how artistic elements should look for porcelains, paintings, or textiles. The emperors defined the blue and white porcelains, the applications of designs, and the thickness of finished products. Porcelains became one of the major exports to European markets. Painters either worked at court, were self-employed, or were supported by wealthy patrons, creating masterpieces still admired today. Because the printing press was invented in China far earlier than in Europe, the Chinese printed and distributed books. During this dynasty, new methods of designing and embellishing books became fashionable along with specific calligraphy styles.

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica had multiple civilizations (1.1.5) with robust territories and trading partners. The Aztecs settled in the swampy land near Lake Texcoco, and after draining the area, they constructed islands and planted gardens with sophisticated irrigation systems able to feed large populations. By the beginning of the 16th century, five to six million people were under the control of the Aztecs, with almost 150,000 people living in Tenochtitlan, the most populated city in Mesoamerica. They had become a military power and built a robust economic system, heavily taxing the subordinate states. They imported a varied range of goods from local states and other flourishing kingdoms.

Figure 1.1.5 Mesoamerican Map circa 1600, Public Domain

Figure 1.1.5 Mesoamerican Map circa 1600, Public DomainAs the Portuguese made extensive gains while controlling the Indian Ocean, rumors of vast amounts of gold and silver in undiscovered places returned to Europe, particularly to the king of Spain. The king established expeditions, and they landed in Puerto Rico, Florida, Cuba, and the Grand Bahamas. The next target was the Yucatan peninsula. In 1519, Cortés took eleven ships, men, horses, guns, and cannons and landed in Mayan territory, declaring the land for Spain. He heard about gold in the Aztec Empire and asked for a meeting with Emperor Moctezuma II, who did not have any interest in meeting with the Spaniards. The emperor did send gifts of gold and silver works and elaborate feathered headpieces and garments to Cortés, hoping to show goodwill, yet avoid any meetings.

Cortés decided to invade and marched with his large army into Tenochtitlan. Although the emperor allowed the strangers into the city, when Cortés heard some of his men left on the coast were attacked, he held Emperor Moctezuma hostage. However, the emperor was killed, and the Spanish soldiers massacred people in the Great Temple, looted the area, and fled back to the coast. Cortés brought in reinforcements, laid siege to Tenochtitlan, captured the new ruler, and claimed the town in the name of Spain.

Art in Mesoamerica was primarily based on gold and silver coming from many mines, one of the significant assets the Aztecs held. They used shiny metals to make jewelry, shields, headpieces, statues, and religious items embellished with beads, jewels, and turquoise. Brilliantly colored feathers were the most valued art material made into headpieces, fans, and extravagant garments used in rituals. The beauty and brilliance of all of the exquisite goldwork and spectacular colors became one of the primary fascinations of the Spanish, who considered everything exotic and worthy of confiscation for their treasury.

Different Art Methods around the World

Oil Paint in the Renaissance and Mannerism Periods

Artists made paint with a colored pigment mixed with a transparent medium having a gummy quality that acts as a binder. Twenty thousand years ago, people created cave art using pigment mixed with animal fat, blood, spit, or water. Over time, techniques improved, and in the European Middle Ages, the pigment was mixed with egg yolk as the binder, producing bright colors. The colors did not mix well, and the paint was prone to flaking.

During the Renaissance and Mannerism periods, oil paint replaced egg tempera paint. Pigment mixed with linseed oil from the flax plant gave the paint flexibility with minimal cracking, although the paint yellowed with age. Walnut, poppy, and safflower were other oils used to mix paint; however, they were not as viscous and tended to crack over time. Oil paint was slow to dry, and the thickness of the paint determined how long it took to dry. The painters created layers with glazing by adding a minimal amount of pigment to the oil and applying a thin layer of paint to the surface. The coating dried quickly, and other layers of glaze could be applied, building up the paint with subtle colors. Light is also reflected in the different layers of paint moving through the various colors and creating the luminosity seen in oil paintings. The plasticity found in oil paint and the luminosity of the light allowed the artists to create realistic images in a diversity of color palettes.

"In Renaissance Italy, the patron saint of painters was St Luke – who was also the patron saint of doctors. Painters didn't have a Guild of their own; they belonged to the same as the doctors. Why? Besides the mythology of the saint himself, it was for the practical reason of painters and doctors both frequenting apothecaries for medicinal and artistic ingredients." [2] New pigments were generally based on natural ingredients available at the local apothecary, some of them toxic.

The Renaissance and Mannerism painters mixed their own colors. They had a wide range of minerals to use besides the basic Naples yellow, smalt, carmine lake (cochineal), vermilion, and madder lake used by Medieval painters. Now they had greens from verdigris, green earth, and malachite; yellows from orpiment, lead-tin yellow; browns from umber; whites from gypsum, lime; and blacks from carbon and bone. These colors and the ability to apply layers allowed a painter to paint chiaroscuro's deep, dark shadows, shafts of illuminating light, or bright red vermillion.

Frescoes in the Renaissance

Frescoes (from the Italian word affresco) were typical in the ancient world until mosaics became the preferred art form. Around the 1300s, the use of frescoes returned, particularly in the monumental architectural structures. Frescoes were a medium able to be created quickly over large surfaces. Fresco meant wet; pigments were applied on the wet wall plaster. A secco is pigment added to a dry wall. The advantage of wet plaster was based on calcium carbonate or lime paste and air trapping the color on the wall.

Painting the large frescoes required scaffolding to cover the distances of the painting. In the 14th century, an artist drew outlines of the design with plaster. By the 15th century, artists drew images on paper, made small holes with a needle, and held the pattern on the plaster, pouncing a small bag of carbon to produce the background. When the plaster was ready for the pigment to be applied, the artist had to select earth pigments that were chemically stable and did not react with oxygen, discoloring over time. When Michelangelo painted the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel, he only mixed enough color to apply to small sections. Sometimes, he had to make several samples to achieve the subtle color he needed, a process occurring repeatedly. The entire process was labor-intensive and time-consuming; however, the frescoes and their colors lasted for centuries unless they were damaged by pollution or water.

During the Renaissance, artists moved from labor-intensive fresco painting to oil painting on canvas for significant works. With the growth of wealthy merchants buying artwork and the economic force of churches as major supporters of artists declining, the use of frescoes faded away.

Marble in the Renaissance

The Renaissance brought a period of renewal in classical art and an interest in marble sculptures. The surviving sculpture from the classical Greek and Roman periods was made of marble. The spectacular Greek bronze statues melted down throughout the ages by other cultures. Generally, only marble survived, becoming the signature of classicalism.

Marble is formed from calcite, changed by heat or pressure into calcium carbonate. The stone is relatively easy to work with when first quarried, is shatter resistant, and hardens with age. Calcite is ranked low on the refractory index allowing light to enter the stone and produce the translucency and appearance of human skin. With the exceptionally fine grain in the marble, artists can sculpt fine details in the stone. Carrara in Italy was the favorite quarry of Renaissance sculptors to procure marble.

Before carving the marble, most artists usually made an accurate, small sample or maquette by constructing an armature and covering it with clay or wax. The artist used measurements on the maquette as reference points on the large block of marble, inserting tacks in specific locations. Today, artists use power tools. Renaissance artists used a mallet and different chisels, first making a rough version of the model, then using more sophisticated tools to carve the detail. When a statue was completed, the marble was sanded and polished to generate a reflective shine. Some artists just carved directly into the piece of marble, for example, Michelangelo, who believed he was releasing whatever human form lay waiting in the stone.

Bronze in the Benin Kingdom

The lost-wax casting method existed in Western Africa for centuries. Benin was organized into guilds that took directions from the local king for design and resulting products. The process may appear easy but was complex, particularly temperature control in the open fires. An artist may make a simple clay shape of a head or plaque and then use beeswax on top of the clay to refine the image or just use beeswax itself to carve a shape. Small pieces of beeswax were added and smoothed to fashion the precisely detailed final image. The finished beeswax was covered with layers of clay slip and then coarser clay, completely enclosing the mold.

The complete assemblage was placed in the carefully controlled fire pit to maintain the correct temperature. The wax melted and was poured out of the mold through a narrow channel, leaving an empty shell to fill with liquid metal. The clay was carefully removed when the metal was hardened, and the metal image was cleaned and burnished. Because the mold was destroyed to remove the image, each casting was unique.

The word bronze was applied to most metal alloys in early cultures, although the metals combined varied. Zinc, copper, lead, or tin was mixed in different combinations, and generally, bronze was considered a mixture of copper and tin, and brass consisted of copper and zinc. Tin was abundant in the region, and the other metals were imported by the Arab caravans or the Portuguese ships. Bronzes were generally reserved for the king as well as selected high-ranking people.

Porcelain in the Ming Dynasty

With the advent of the new dynasty came a renewed interest in the revival of pottery, particularly in Jingdezhen, where the emperor constructed the new imperial factory. Jingdezhen became the primary production center for porcelain. The area neighbored the mountains with caves of raw material of kaolin (a fine white clay) and petuntse, sometimes called china stone (from feldspathic stone). The two materials were mixed; the kaolin gave the porcelain its strength letting potters make exceptionally translucent, thin-walled pottery. The vessels were made on a potter's wheel, painted and glazed, and fired in high-temperature kilns.

The fine white clay presented a clean, fine background to paint elaborate designs. Initially, the preferred color became the blue underglaze. The cobalt blue pigment was imported from present-day Iran, probably formed into a block for easy transportation. The cobalt was crushed into powder and used to paint the first layer of the design, then other colors were added as the overglaze. In the early 1400s, the blue was dark, the brush forming dark spots from blobs of paint giving a piled look. Usually, the motifs favored floral, or fish images, and the new concept of waves splashing against a rock was considered the Isle of Immortality. The late 1400s added other softer colors to the overglaze producing a more defined visual image. In the early 1500s, yellow was integrated into the overglaze and Muslim design graphics in the shape and scroll-like appearance of flowers and leaves. Red and green were introduced, and the green often paired with yellow to fashion the image of a dragon. Near the end of the 1500s, most common porcelain was painted with an underglaze of blue and the previous red, green and yellow, and the addition of aubergine purple and iron red. This set of colors became known as Wanli five-color.

Most of the porcelain was produced for the trade routes as a significant trade product. However, unique imperial porcelain was made solely for the emperor's court, especially elegant and designated with the official mark of the emperor. By the end of the Ming dynasty, the thousands of potters working in terrible conditions protested. In the early 1600s, the official kiln of the emperor stopped producing royal porcelain.

Calligraphy in the Ming Dynasty

Calligraphy was part of personal expression, the process, shape, and form of each symbol were as important as the meaning. The look of a symbol differed depending on the style and how the brushstrokes were made. Calligraphy became a form of self-expression. Chinese script is composed of several thousand unique characters based on a set of strokes. The calligrapher applied the strokes quickly or slow and deliberate, with force or a delicate touch; each stroke is definable and observable.

Calligraphy became integrated into art, painting, writing, and poetry following a prescribed methodology. During the Ming Dynasty, artists began to develop their style, liberating themselves from tradition. Learning to be a master of calligraphy took years of practice based on four stages of an artist's process; first, observation or guan, the artist must spend time watching and learning from others. Then the artist is ready to emulate, lin mo, tracing or copying other works, practicing, learning how to hold the brush and apply pressure, mixing ink, mentally preparing to write a character, and understanding the spiritual appreciation of each stroke. The next stage is understanding or comprehension, wu, reaching maturity in life, and finally the ability to create new styles, tsung, only achievable by the mature, elite masters of calligraphy.

The brush, ink, and inkstone were the essential elements needed. Brushes were generally made from natural materials, bamboo, wood, or porcelain, with selected animal hair for the bristles. Lampblack and binders were mixed for the inks and formed into a stick. An inkstone, made from stone or ceramics, contained a small well for water to mix with the ink. Most calligraphers preferred special paper prepared from rice, mulberry, or other natural elements. The size of the brush, type of paper, ink density, and the strokes the calligrapher makes all influence the results.

Ink and gold in the Kano School

In the Kano School, the main emphasis was on brushwork and how ink or ink washes were applied. Artists used clearly defined lines with the brush to develop illusions of space and depth, for example, misty mountains thrusting out of vast foggy valleys. Three basic types of defining work were included; a loose, less formalized brushstroke (so), a formal variety, precise (shin), and a style in-between (gyo). Early artists frequently used a softer vertical design, while later artists followed a horizontal style and added bold strokes, bright colors, and vibrant gold leaf.

Large folding screens were used to decorate the walls and enclose spaces in the dimly lit castles or temples. The screens were decorated with scenes of the outdoors using bold yet delicate brushstrokes and vivid colors. Gold leaf brought a radiancy and ambient light to the rooms to reflect light and better illuminate the paintings. The screens were six to eight panels across and made with a frame and thin wooden strips. Several layers of paper covered the strips, and then the final layer of quality paper or silk was added. The panels were assembled with paper hinges, and the exterior frame was generally painted with black lacquer.

Sculpture in Mesoamerica

Sculptures were an essential part of Aztec culture, communicating religious concepts and portraying images of the gods and goddesses. Sculptors used simple stone tools and cords to carve with water and sand for finishing. Sculptures might be low relief, in the round, or both. Sculptors had general conventions they followed when carving; almost every figure was shown with a frontal view. Depending on the deity being represented, the statue might be adorned with claws, fangs, or other animal attributions. Serpents were common images also wrapped around some part of the statue, the head, fangs, and body patterns are integral parts of the image. Every god or goddess was recognizable by their dress or decorative elements, and statues were found everywhere in all sizes. Unfortunately, the Spanish destroyed most of the statues and a significant amount of the Aztec culture. The video 1.1.15 is about Coatlicue, one of the most famous statues in Mesoamerica.

Gold in Mesoamerica

Gold in the Aztec Empire was mainly used for jewelry and personal adornment, although religious beliefs were often part of the necklace, armband, or ring. Gold was an important part of funerals, a tribute to the status of the person who died and offerings to the divine gods. Raw gold was mined and brought from other parts of Mexico the Aztecs controlled. Placer mining was the primary way to gather gold, and evidence of sophisticated mining was found. Gold represented power and authority, and the emperor controlled the mines and who had gold, frequently giving gold to other rulers to maintain peace. Much of the gold was formed into ingots until an artist needed it.

The artisans made gold ornaments by the lost wax method, each made in different and unique clay molds or hammered sheets of gold into decorations resembling low relief sculptures. Elaborate necklaces were made for different professions or sex and resembled jaguar teeth, frogs, snake rattles, or other essential images. The higher the person's status, the more extravagant the jewelry became. The video 1.1.16 explains the luxury and the legacy of gold in the Kingdoms of Mesoamerica.

[1] Corbett. P. et al. (2014). US History. Open Stax. Retrieved from https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-2-europe-on-the-brink-of-change

[2] Mellow, G. (2011). The chemistry of oil paintings. Retrieved from https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/symbiartic/httpblogsscientificamericancomsymbiartic20110802the-chemistry-of-oil-painting/. March 12, 2020.