1.1: A Brief History of Early Photography

- Page ID

- 231804

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The early technical and artistic history of photography is characterized by a reciprocal relationship between technological innovations and the social, cultural, and artistic uses of the medium. Although the theories underlying the camera were known in antiquity, the chemical processes involved in creating images were not known until the nineteenth century.

The Camera Obscura and Early Photographs

A camera obscura (“dark chamber” in Latin) is a device that contains a small hole for light to pass through and projects an inverted image of an external object. Although it dates to ancient Greece and the Chinese Han Dynasty (c. 468 – 391 BC), Idn al-Haytam (965-1050) was a medieval scientist and mathematician known as the earliest user of the camera obscura. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519),1 who was familiar with al-Haytam's work, even described it in his Codex Atlanticus (1502).2 Renaissance artists in the sixteenth century used camera obscuras to project an inverted image of a subject onto paper that could be traced to produce a highly accurate representation. Camera obscuras were used until French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833) developed heliography, the process of photoengraving an image on a light-sensitive surface. This technological advancement marks the birth of photography.

Image Description: A grainy photograph showing a somewhat vague view of buildings and rooftops.

After this point, innovation in the field of photography developed in three areas: speed or exposure time, resolution or the clarity of an image, and permanence. Early photographs, such as Niépce’s famous View from the Window at Gras (1826), were created only through excruciatingly long exposure periods, i.e., a very slow shutter speed. View from the Window boasts a shutter speed of approximately eight hours. This gradual transference of images meant the artists were limited in their subject matter. To capture View from the Window, Niépce set up a camera obscura to expose a silver and pewter-coated copper plate across the day. It is blurry and the resolution, or clarity, is grainy due to natural changes in conditions outside his window during that long exposure time. Niépce’s work also suffered from the lack of permanence of the images he captured. His medium would continue to react to light as time passed, eventually turning black. He did not solve this problem in his lifetime but, in 1839, the chemical hyposulfite of soda, nicknamed hypo, was invented, which allowed images to be more permanently fixed to paper.

Image Description: A black and white photograph of objects on a table including two plaster angel heads below a coat, large flask, and framed picture hanging from the wall.

Photographers after Niépce experimented with a variety of techniques. Louis Daguerre invented a new process that, after experimenting for several years, he presented to the French Académie des Sciences in 1839. His discovery, which he named daguerreotype, significantly reduced exposure time and created a lasting image. The daguerreotype process did not allow for prints to be made of the image, however.

Image Description: A salted print photograph with gold tones depicting an open barn door with a broom leaning diagonally to the left of the door frame.

At the same time, Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting with what would eventually become his calotype method, patented in February 1841. Talbot’s innovations included the creation of a paper negative, and new technology that involved the transformation of the negative to a positive image, allowing for more than one copy of the picture. The remarkable detail of Talbot’s method can be seen in his famous photograph, The Open Door (1844), which captures the view through a humble stable door. The texture of the rough stone structure, the vines, the rustic broom, and the bridle hanging from the hobnailed door demonstrate the minute details captured by Talbot’s photographic improvements.

The collodion method was introduced in 1851. This process involved fixing a substance known as gun cotton onto a glass plate, allowing for an even shorter exposure time of three to five minutes and producing a clearer image.

The main disadvantage of the collodion process was that it needed to be exposed and developed while the chemical coating was still wet, which meant that photographers had to carry portable darkrooms to develop images immediately after exposure. Nadar, born Gaspard-Félix Tournacho, one of the most prominent photographers in Paris at the time, was known for capturing the first aerial photographs from the basket of a hot air balloon using the collodion method. Both the difficulties of the method and uncertain but growing status of photography were lampooned by Nadar’s friend Honoré Daumier in the lithograph Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of Art (1862).

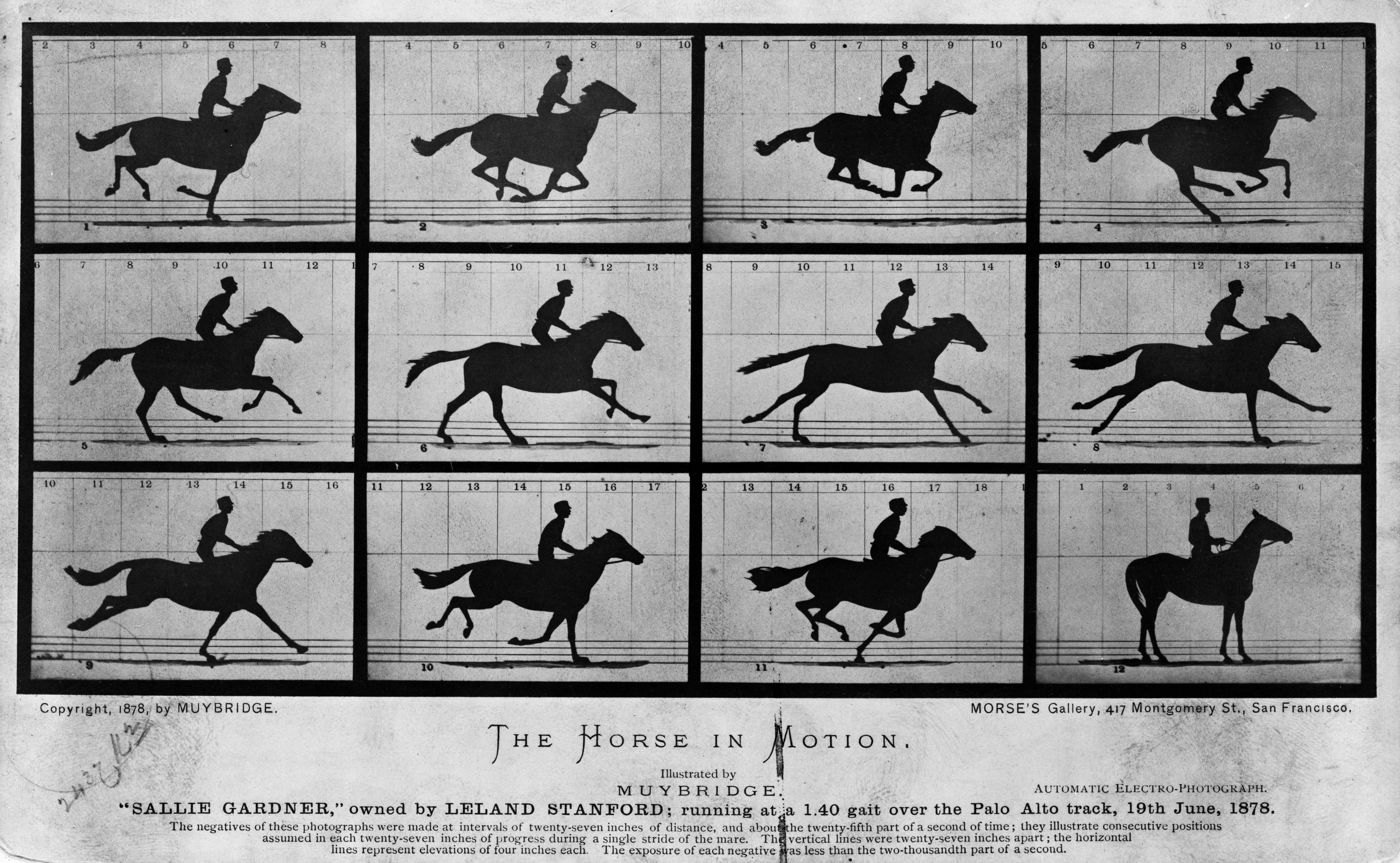

Image Description: A series of black and white silhouettes of a horse and rider in various stages of motion in a table of four columns and three rows.

Further advances in technology continued to make photography less labor-intensive. By 1867 a dry glass plate was invented, reducing the inconvenience of the wet collodion method.

Artists could purchase prepared glass plates, eliminating the need to mix chemicals. In 1878, new advances decreased the exposure time to 1/25th of a second, allowing moving objects to be photographed and lessening the need for a tripod. This new development is celebrated in Eadweard Muybridge’s sequence of photographs called The Horse in Motion (1878). Designed to settle the debate of whether all four legs of a galloping horse ever come off the ground at the same time, the series of photographs also demonstrated the new photographic methods that were capable of nearly instantaneous exposure.

In 1888 George Eastman developed dry gelatin roll film, making it easier for film to be carried. Eastman also produced the first small, inexpensive cameras, allowing more people access to the technology.

Photographers in the nineteenth century were pioneers in a new artistic endeavor. Frequently using traditional methods of composition married with innovative techniques, photographers created a new vision of the material world. Despite the struggles early photographers faced with the limitations of their technology, their artistry is obvious.

References

Dr. Rebecca Jeffrey Easby, "Early Photography: Niépce, Talbot and Muybridge," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2023. https://smarthistory.org/early-photography-niepce-talbot-and-muybridge/. Used under the Creative Commons attribution share-alike license.

[1] Abdelghani Tbakhi and Samir S Amr. “Ibn Al-Haytham: Father of Modern Optics.” Annals of Saudi Medicine 27, no. 6 (2007): 464-7.

[2] Shira Wolfe. "Agents of Change: Camera Obscura." Artland Magazine. https://magazine.artland.com/agents-of-change-camera-obscura/.