5.3: Narrative Compositions

- Page ID

- 170518

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Everyone has a story to tell. As soon as we start telling it, we become the narrators of a narration. The terms are interchangeable. Have you ever heard anyone discuss "controlling the narrative"? A conscientious writer is in control of how her choices may come across to the reader, is able to tell stories with engaging qualities like concrete imagery (description) and specific examples/allusions. Any narrative should involve some level of irony, or trouble, and there should be some focus on characterization, or the people involved, unless it's some story like The Brave Little Toaster, which is still, after all, mostly about the people in the family who own the appliances.

Now think of the word trope

These common themes, these forms, are referred to, in general, as tropes. You'll learn more about tropes as you take more college courses, but, to give you a relatable example, one trope of scary stories is that they take place "on a dark and/or stormy night," generically speaking. Other horror genre (remember that word?) tropes involve cemetery scenes, labyrinths, puzzles or mazes, and the occasional person with an outwardly unconventional physical feature (or set of features) who is either inwardly kind (Quasimodo of The Hunchback of Notre Dame; the creature of Frankenstein) or, often, written to be evil (Leatherface of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre; Jason Voorhees of Friday the 13th; Freddy Kreuger of The Nightmare on Elm Street; and arguably Michael Myers of Halloween). Although this is not fair (ethical) to those who have no choice over their physical appearances, it just works out that, historically, within the canon of literature that we have produced internationally, physical appearances belie mental idiosyncrasies. There is almost no greater example from popular culture than Frankenstein's creature (or monster, as you will), who is outwardly repulsive but inwardly neutral until he realizes that people will never accept him within their strict boundary, or definition, of what is human. After he comes to this epiphany, being rejected by those he comes to love who are human, denied by his creator the making of a mate, he turns on humanity and his creator. Another fascinating literary example is found in Oscar Wilde's novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. The titular character has a portrait created of himself that has magical properties. Instead of Dorian's physical appearance aging or changing with his lifestyle choices and throughout time, the portrait becomes disfigured. Essentially, this is an allegory about the staining of the human soul despite maintaining outward appearances. When creating these characters and developing their stories, these writers may or may not have thought deeply about the tropes they were employing, but these forms help establish the meaning intended to be communicated by telling the stories in the first place.

Narrative and Form

Any narrative must have a beginning, middle, and end. This is what defines a story. Many writers refer to Freytag's Pyramid when discussing the forms that narratives take, which is a formal depiction of storytelling as created by Gustav Freytag, a German playwright who wrote in the 1800s. His pyramid looks like this:

Sample Narration Essay: Ocean Vuong, "Surrendering"

About the Author

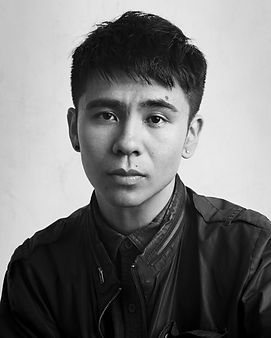

Photo: Tom Hines

Ocean Vuong, a tenured professor of creative writing at NYU, is also known for his extraordinary poetry and prose writing, including "Surrendering," which was featured in The New Yorker. This autobiographical essay inspires and gives insight into the beautiful literary mind that came to the United States from Saigon, Vietnam, and has since grown to be a towering inspiration for young poets and writers, especially those who come to writing from juxtaposed backgrounds and fluid identities. Truly a voice of the new generation of American writers, Vuong narrates his experience as a transnational writer; this essay offers a window into his grappling with writing in the alien English language he was forced to adopt.

"Surrendering" by Ocean Vuong

Questions for Discussion

- Describe the genre, intended audience, and purpose of this written work by Ocean Vuong.

- How is learning English comparable to immigrating?

- What do you think about the way Vuong describes his elementary school experience in the United States?

- What does Vuong mean when he writes, "I was a fraud in the field of language, which is to say, I was a writer?"