5.4: Qin Dynasty (221 BCE – 206 BCE)

- Page ID

- 219984

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

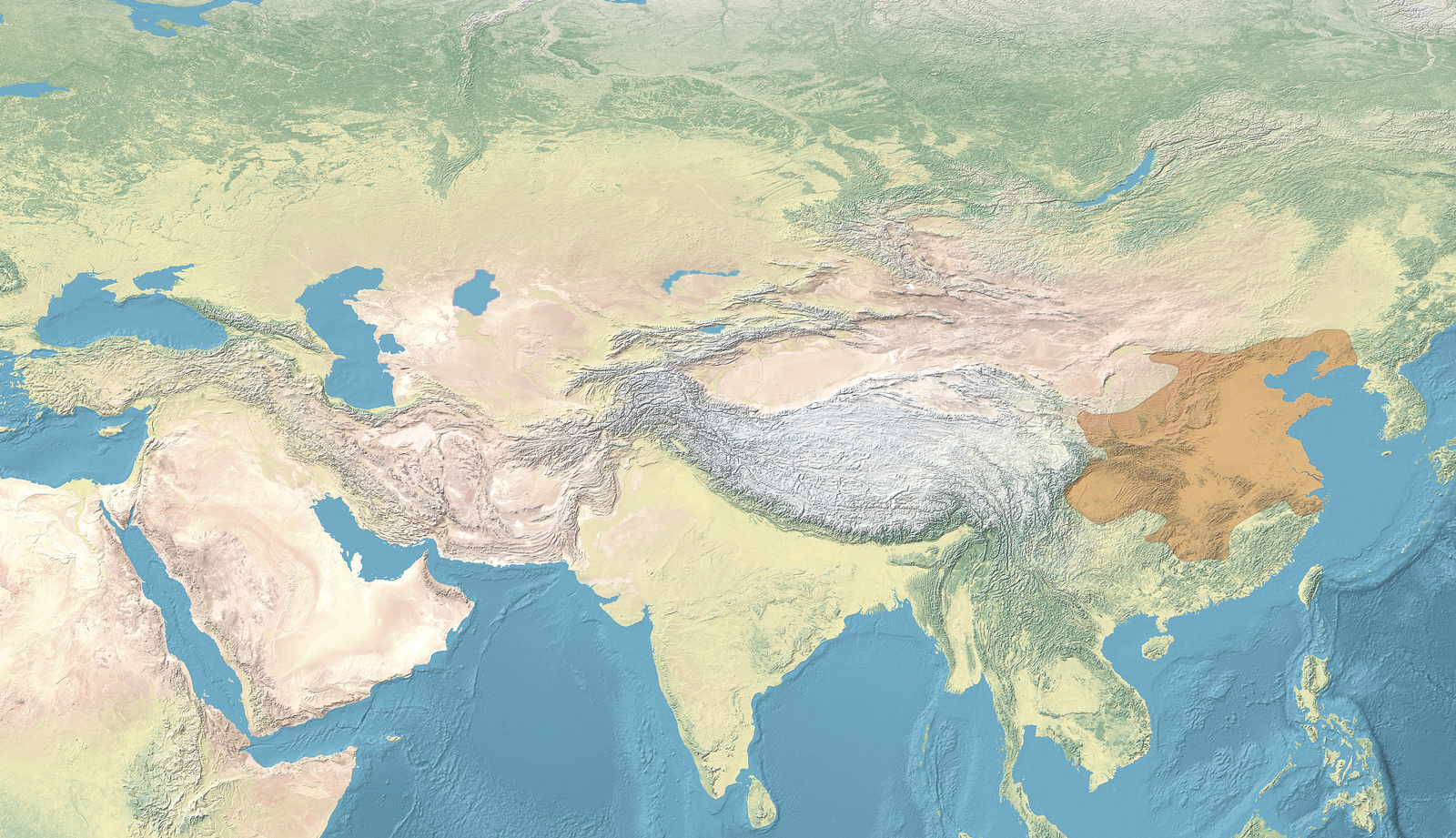

Historically, the Qin dynasty (5.4.1) existed for a very short period from 221-210 BCE, however, the time was significant in Chinese history. During the Warring Period, Qin Shi Huang emerged as the conqueror of the region. As the new emperor, Qin Shi Huang consolidated the disparate states into one Chinese government, naming himself emperor, a title used in China for two thousand more years. He developed and implemented multiple unique elements into the newly formed government including standardized currency, consistent definitions for writing, and uniform measurements. Qin Shi Huang is known for his architectural achievements including the start of the Great Wall, creating an extensive national road and canal system, and especially remembered for his elaborate mausoleum and tomb with the Terracotta Warriors.

The emperor incorporated the ideals of Legalism into his rulings and changed how the government worked. He brought centralization and control to his government instead of adherence to localized standards and laws as he abolished all the assorted feudal systems in existence. The power of the elite was restricted as people reported on each other and creating an atmosphere of fear and dissatisfaction. Confucianism, Daoism, and other philosophies were suppressed. Qin Shi Huang was known for his brutality and individual life had little meaning as the power belonged to the state The emperor executed scholars and burned books, and with a powerful military, did not hesitate to take new territory and enslave or kill people.

The Great Wall

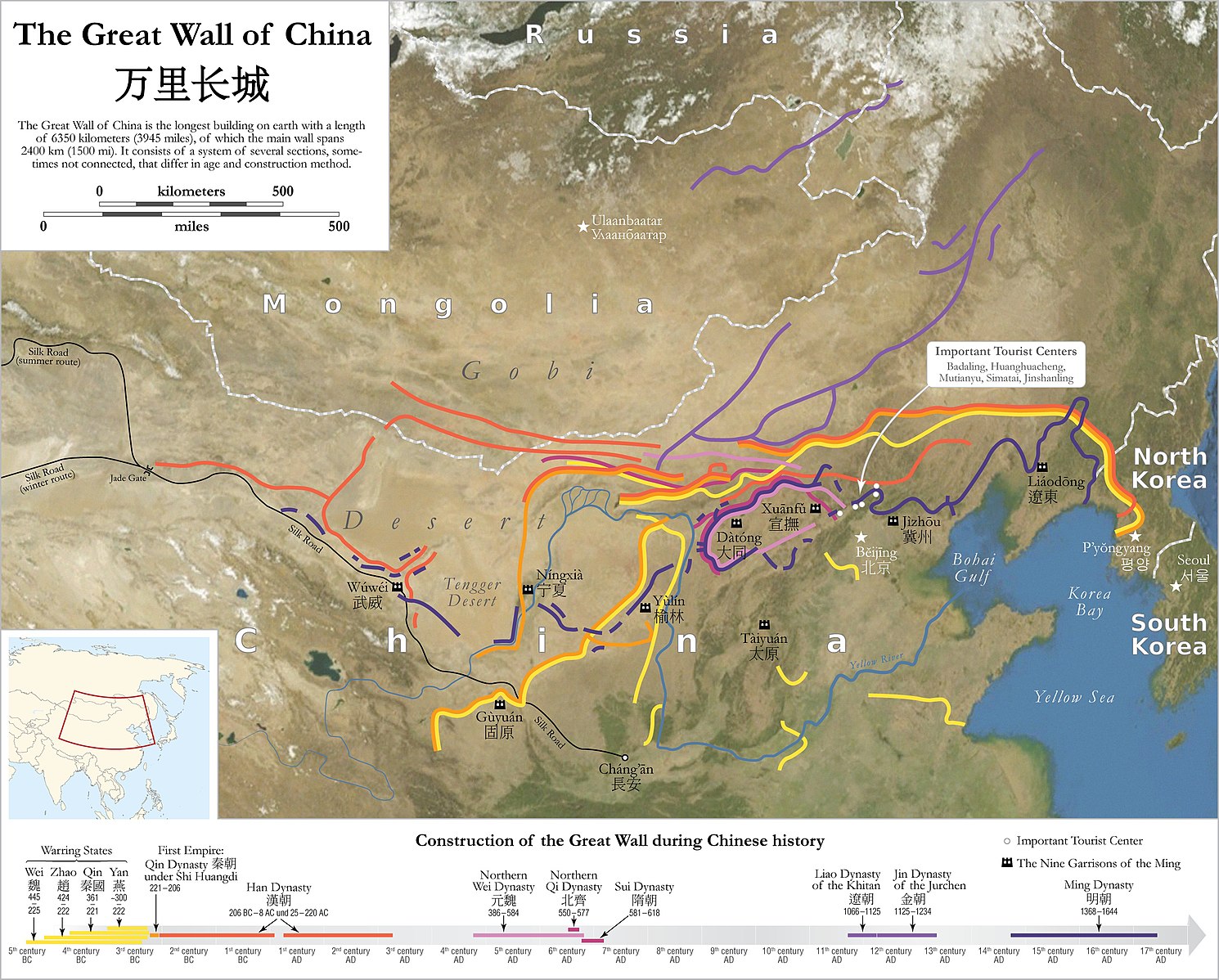

Before the Qin Dynasty, each separate city/state had their own walls, towers, and gates to defend the cities and protect the local ruler. After Qin Shi Huang unified the various city/states, he had the unique defense structures removed. The new country only needed a wall at the northern border where the Xiongnu lived and continually attacked the old city/states and newly formed country. The emperor started the construction of the ‘Great Wall”. The map (5.4.2) outlines the complete wall through multiple dynasties for centuries.

The conditions of building in the mountains were complex with heat, cold, and lack of water and food. Some estimate thousands of people died during just the construction of the Qin sections. The terrain the wall (5.4.3) ran through was exceptionally challenging and hauling materials difficult. The wall went on for miles and local stone from the mountainous regions was used with rammed earth method used in the plains. The wall was a defensive construction to keep others out. It also allowed the government to impose duties on goods moved on the Silk Road and regulate immigration. The Great Wall had watchtowers and barracks for troops. A signaling method was part of the wall by using smoke to signal to the next tower. The wall became a transportation corridor to allow goods and people to easily move across regions.

Today, parts of the wall (5.4.4) have been restored and demonstrates the detail and decorative elements included in the wall. The towers allowed the guards to stay out of the elements and maintain their watch. The construction of the wall sat on top of the mountain ridges, and it is easy to see the complexity of finding and cutting stone and carrying and stacking the stone was truly an engineering feat. The second section of the wall (5.4.5) as not been restored today. However, some of the blocks of stone are still visible in the wall and boulders protrude from the worn walkway. Throughout the centuries, people have vandalized the wall to use the stones to build houses or roads. The wall has even been a canvas for graffiti. Weather, particularly sandstorms, have eroded some of the wall. The parts of the wall near major cities have been restored, mainly for tourists. The wall (5.4.6) in flatter or desert areas were constructed of rammed earth or large bricks. Sticky rice mortar was used to hold the bricks together. The mortar was made with rice soup and slaked lime. The wall in Jiayuguan is located in the most westerly point of China. Few watchtowers were installed because the visibility was so good across the flat desert region.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=889&height=592)

The Great Wall Of China was built to protect a growing empire and the Silk Road that brought in wealth, but how exactly was the wall built?

Hydraulic Engineering

“In ancient China, large canals for river transport were used during the Warring States Period (481-221 BCE). The Dujiangyan is irrigation infrastructure built in 256 BCE by the State of Qin and is still used to irrigate an area of over 5,300 km. The Dujiangyan, along with the Zhengguo and the Lingqu Canal are known as the three great hydraulic engineering projects of the Qin dynasty. The longest canal was the Grand Canal of China; at 1,794 km long, it remains the longest canal in the world. The oldest parts of the canal date back to the 5th century…”[1]

During the Qin dynasty a diversion embankment called Yuzui (looked like a fish mouth) was built in the middle of the Minjiang River, one of the major tributaries of the Yangtze River and located where the river comes out of the mountains. Channels (5.4.7) were also built to help control flooding and provide irrigation for farmland. Li Bing headed the project and he invented a new method to divert water with and artificial levee. He took woven bamboo baskets (zhulong) made into the shape of a sausage. The baskets were loaded with stones and held in place in the water with wooden stakes. With the water diverted, Li Bing had to remove hard mountain rock. Gunpowder was not invented at the time. To cut the channel through the rock, he heated the rocks with fire. After the rock was heated, water was poured on them to crack the rock. The work for the channel took over eight years.The Zhengguo and Lingqu Canals were also fabricated during the Qin dynasty. Both canals diverted water for control and irrigation. These three systems are considered some of the greatest engineering projects in China and still used today.

During the next dynasty, the Han, a statue of the engineer Li Bing (5.4.8) was created and placed in the river to monitor flow. When the water reached the statue’s shoulders, a flood was indicated and if the river fell below his calves, a drought occurred. The statue sat in the river until 1974 when it was recovered and put in the main hall. The statue is the oldest known stone statue in China of a human.

Terracotta Warriors

“As the sun rose over the fields of Xi’an, Shaanxi Province on the 29 March 1974, a group of Chinese farmers set off for a day’s toil unaware of the astounding discovery they were about to make. There had been reports of fragments of terracotta figures in the past, but as the farmers dug a water well that morning, they uncovered one the greatest archaeological sites in the world. One can only imagine the intrigue and bemusement they must have felt when, after digging 5 m down into the loess sediment that had accumulated over the past 2000 years, they suddenly saw terracotta faces peering up at them. The first of an estimated 8000 Terracotta Warriors were emerging from the necropolis.”[2]

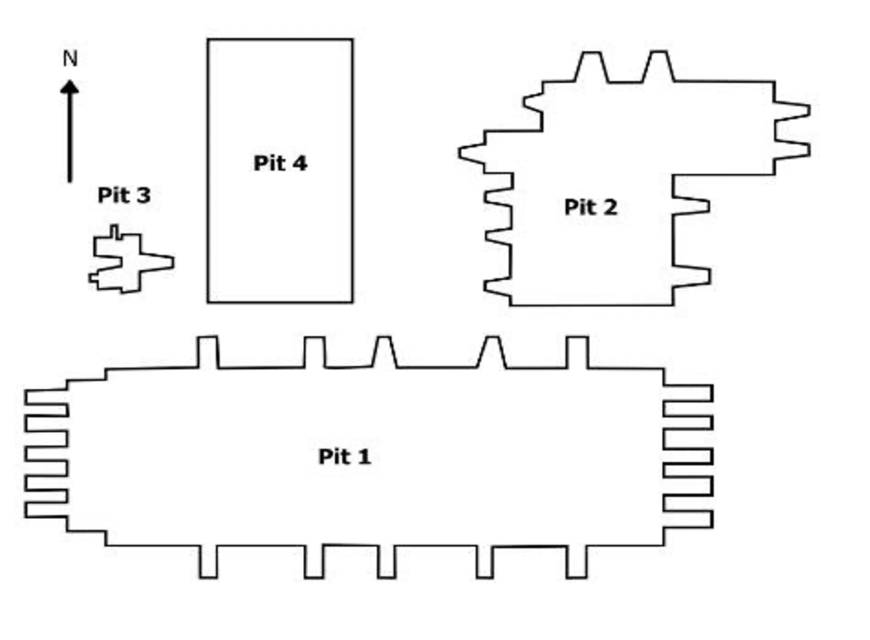

The emperor’s tomb and the outside environment took over thirty-five years from 246 to 208 BCE to construct. The tomb was made for the emperor and the support of his afterlife. Attending the emperor were about 8,000 terra cotta warriors, all standing in rows based on rank and heights beginning with the generals. Along with the warriors were almost 700 life-sized horses as well as chariots. Government officials, musician, and acrobats were also found in the complex, each one with distinctive facial features. The specific tomb holding the emperor remains sealed today and probably contains additional artifacts. Four pits (5.4.9) were excavated on the eastern side and the standing warriors appear to be guarding the emperor from an invasion on the eastern side. The pits were five to seven meters deep in the ground with the warriors arranged in long corridors or small adjacent rooms.

Pit no. 1 (5.4.10) was the largest pit and contained the main army of 6,000 soldiers (5.4.11) standing in eleven corridors made three meters wide. Small pavers covered the floor with large wooden post and beams holding up the wooden ceiling. Reed mats and layers and layers of clay and soil covered the entire project. The soil was raised two to three meters higher than the surrounding land. The view of the pit today resulted when researchers removed the roof and massive roof beams, exposing the warriors. Historians generally believe the construction of the pits started around 221 BCE when the Qin Empire was unified. “Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian records that at the time over 700,000 convicts and forced laborers were relocated to the tomb construction site. While some doubt this many laborers were used, archaeological evidence and our understanding of how the soldiers were made support this timeline. It was this massive workforce that managed to dig out Pit 1, removing what is estimated to be around 70,000 cubic meters of earth, the equivalent of the carrying capacity of 5,500 modern lorries!”[3]

Pit no. 2 was divided into four sections. On section contained two rows of archers and spearmen and six columns of archers. Some of the archers were standing and others kneeling. Another section encompassed the sixty-four spectacular chariots including four horses for each chariot, a driver, and two aides. Another smaller set of chariots and some infantrymen were located in another section. And in the last section, archaeologists found six chariots and over one hundred cavalrymen and their horses.

Pit no. 3 was the most unusual and sparingly populated with a few infantrymen who are facing each other. They appear to be waiting for someone. In another part of the pit was an elaborately decorated chariot (5.4.12), quite different from the other chariots. The chariot was probably for a high-level commander or maybe the emperor himself. Pit no. 4 was empty.

In March 1974, Chinese farmers digging a well unearthed the greatest archaeological find of the century - the buried Terracotta Army. After coming across a life-sized human head made of clay in Xi’an, China, archaeologists were called in to investigate. What they found was extraordinary. Thousands of life-like terracotta figures from the Qin dynasty, fashioned 2,000 years ago to protect the First Emperor of China in the afterlife. Archaeologist Li Xiuzhen has worked on the site since the 1980s. Her team was the first to discover that each warrior was originally painted in bright colours.

All of figures of the warriors were life-sized and were constructed with unique features. Every person had varying facial features and hair styles as though they were modeled after real people. The figures were posed to represent their rank, position, or role; a bowman was placed in a kneeling position, ready to shoot. Charioteers had their arms outstretched as though they were holding the reins in their hands and infantrymen stood with one extended arm and the other arm folded up against his chest.

Another unique feature was how the figures were dressed based on their military assignments. The chariot drivers were helmets, and the cavalry wore hats shaped like pillboxes, some of the coats were padded and others had on short pants. Because each figure was unique, artists had to create unique solutions.

The figures were constructed with the coil technique for the clay making firm, steady legs, and feet as a base. The feet and legs are thick and made by making rolls of clay similar to a drainpipe. The legs needed to hold the weight of the rest of the figure. The lower portions of the body and torsos were made with slabs or coils of clay with additional pieces added to develop the detail. Arms, heads, and hands were created by adding clay to a mold and then attaching them to the torso with a clay slip. “There was only a limited number of molds being used for every part of the body: two types have been identified for the feet, three for shoes, eight types of torsos, two types of hands, and eight types for faces”[4]. The rest of each figure was created in part and assembled. Then strips of clay were used to hold the parts together. The figures were assembled, fired, painted, and placed in their proper place.

Every figure wore extremely detailed clothing (5.4.13). In the image, the warriors appear to be wearing the same coat with strips of overlaid material and small knobs or buttons. However, the warriors have different hats and hair arrangements perhaps indicating the differences in rank. The heads and faces were made in molds and carved to achieve the uniqueness of each person regardless of age or superficial marks. The eyes on the figures might look back at the viewer or it may have closed eyes. The men usually wore their hair in a bun; however, some may have a hat on or, long hair, or a braid. Moustaches and beards might be long or thin, or cut into a specific design. A few did not have any facial hair and historians believed those people might be teens.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=944&height=524)

“Qin’s army of clay soldiers and horses was not a somber procession, but a supernatural display swathed in a riot of bold colors: red and green, purple and yellow. Sadly, most of the colors did not survive the crucible of time—or the exposure to air that comes with discovery and excavation. In earlier digs, archaeologists often watched helplessly as the warriors’ colors disintegrated in the dry Xian air. One study showed that once exposed, the lacquer underneath the paint begins to curl after 15 seconds and flake off in just four minutes—vibrant pieces of history lost in the time it takes to boil an egg.”[5]

Although most of the vivid colors painted on the figures have faded away, some of the color is still visible on the crevices of their clothing. The colors highlighted every detail of the uniforms and how each warrior looked unique. Today, examples (5.4.14) of how the painted warriors appeared originally was recreated with bright colors in elaborate patterns. Each warrior had a robe painted to relate to their rank and unit they represented.

“Some warriors wore green robes, dark blue trousers, black shoes with red laces, black armor plates with white rivets, purple cords, and gold buttons. Others wore shorter red robes, brown armor plates with red rivets, and orange cords or buttons. All their faces were flesh tone, their eyes white, and their irises, eyebrows, hair, and whiskers black.”[6

In the pits, archaeologists also found weapons which were mass produced. Spears, daggers, swords, axes, or lances were made from metal and survived intact creating a comprehensive record of the period’s weapons. Cross bows, bows and arrows and other weapons made from wood were decayed, however the metal parts survived, and researchers were able to reconstruct the weapons.

Because the clay soldiers laid in water-soaked soil for over 2,000 years, the figures started to dry causing the glaze to fall off. Today, scientists are covering the figures with a chemical used to make plastics and bombarding them with a particle accelerator to bond the coating. Currently this technique is helping preserve these important figures.[7] Historians do not know is each figure was based on an actual person or only creations. The terracotta figures were part of the emperor’s support for his journey into the afterlife.

Written Language

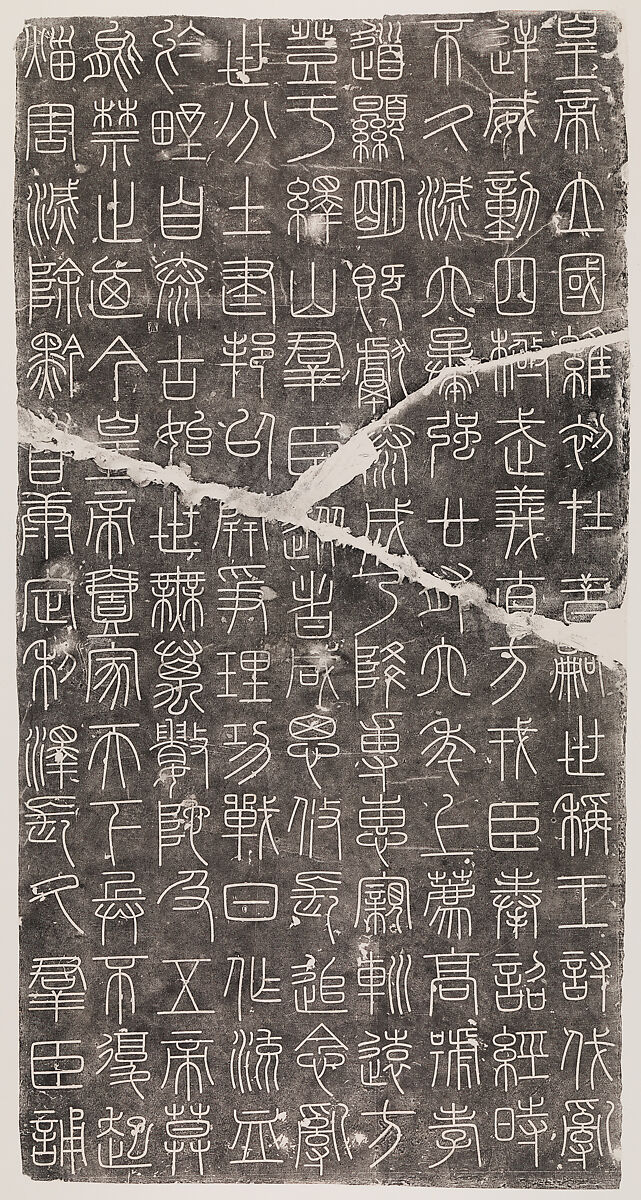

“In 219 B.C., on the first of many inspection tours of his vast empire, the First Emperor of Qin visited Mount Yi. He ordered that a stele be erected there, and calligraphic with a text in the newly standardized script (5.4.15). The text praises the emperor for bringing peace to the world by defeating Qin’s six rival states and unifying them under his rule. Although the stele was destroyed by fire during the Tang dynasty (618–907), the inscription was passed down by scholars; the present rubbings were taken from a stele that dates from the tenth century A.D. While the calligraphic style is of that era, the balanced structure and relatively uniform size of the characters derive from the seal script established by the Qin, echoing the glorious tradition of this mighty but short-lived state.”[8]

The incised stones (5.4.16) were named the Stone Drums of Qin because of their unusual shape. The stones were incised with descriptions of different activities about a specific battle or hunting and fishing. The size of the stone defined the numbers of inscriptions incised in the stone. Larger stones held at least fifteen lines and smaller stones up to nine lines. The characters were carefully arranged into a grid-like pattern. Many of the lines were poetic and rhymed. The stones were inscribed in the Qin dynasty and throughout the centuries, other people have added writing or painted the stone, further damaging them.

“…the Qin dynasty collapsed within two decades because it did not change enough. Despite its proclamations of making a new start in a world utterly transformed, the Qin carried forward the fundamental institutions of the Warring State era, seeking to rule a unified realm with the techniques they had used to conquer it. The Qin’s grandiose visions of transformation failed to confront the extensive changes that the end of permanent warfare had brought about. It fell to the Han, who took over the realm after the Qin dynasty’s defeat, to carry out the major institutional programs and cultural innovations that gave form to the vision world empire.”[9]

[1]Flambas, P. (2016). Plato’s Caribbean Atlantis: A Scientific Analysis, Vivid Publishing.

[2] Rees, S. (March 6, 2014). Education in Chemistry, Royal Society of Chemistry.

[5] Larmer, B., (June, 2012). Terracotta Warriors in Color, National Geographic Magazine.

[6] Schulman, H., (April, 1993). Faces, 9(8), p. 22.

[7]Ball. P. (November 27, 2003). Terracotta Army Saved from Crack Up, Nature International Weekly Journal of Science.

[9] Lewis, M. E., (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, Belknap Press, p. 51