12.3: The Zapotec

- Page ID

- 72305

Learning Objective

- Explain the culture, religion, expansion, and demise of the Zapotec civilization

Key Points

- The Zapotec civilization originated in the three Central Valleys of Oaxaca in the late 6th Century BCE.

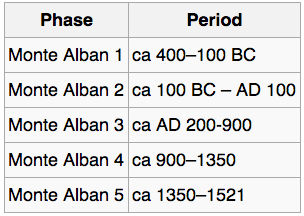

- There are five distinct Zapotec periods, denoted Monte Albán 1–5 (after the place of origin).

- The Zapotec were polytheists who developed a calendar and logosyllabic writing system.

Terms

Monte Alban

The place of origin for the Zapotec civilization.

Cocijo

The lightning and rain god of the Zapotec civilization. He was the most important of the religious figures and was believed to have created the universe with his breath.

Mitla

The main religious city of the Zapotec culture. Elaborate buildings and artwork display the richness of religious life for the Zapotec elite.

The Zapotec civilization originated in the three Central Valleys of Oaxaca in the late 6th Century BCE. The valleys were divided between three different-sized societies, separated by no-man’s-land in the middle, today occupied by the city of Oaxaca. Archaeological evidence from the period, such as burned temples and sacrificed captives, suggests that although the three societies shared linguistic, cultural, and religious traditions, they also competed against one another.

Five Phases

The Zapotec state formed at Monte Albán. This consolidation of power began outward political expansion during the late Monte Albán 1 phase (400–100 BCE) and throughout the Monte Albán 2 phase (100 BCE–200 CE). Zapotec rulers from Monte Albán seized control of provinces outside the valley of Oaxaca with their superior military and political clout, which quickly overtook less-developed local entities. By 200 CE, the end of the Monte Albán 2 phase, the Zapotecs had extended their influence, from Quiotepec in the North to Ocelotepec and Chiltepec in the South. The religious and cultural city of Monte Albán had become the largest city in what are today the southern Mexican highlands. This powerful city retained this status until approximately 700 CE.

Expansion and Decline

Between Monte Albán phases 1 and 2 there was a considerable expansion of the population of the Valley of Oaxaca. As the population grew, so did the degree of social differentiation, the centralization of political power, and ceremonial activity. Another effect of this population boom and the political expansion of the military during Monte Albán 1–2 was the development of fragmented, independent states. These areas developed regional centers of power with distinct leaders and linguistic dialects. However, the Zapotec rulers retained control over vast swaths of the region. Some archeologists argue that the building centered on the main plaza of Monte Albán contains depictions of elaborate heads, which represent the rulers of conquered provinces.

The Zapotecs were ultimately destroyed by Spanish invaders. Having lost militarily to the Aztecs in battles from 1497–1502, the Zapotecs tried to avoid confrontation with the Spaniards, and hopefully the tragic fate of the Aztecs. The Spaniards took advantage of this pacifist stance and ultimately defeated the Zapotecs after five years of campaigns ending in 1527. The arrival of new diseases and steel weapons also weakened any attempts at a revolt from the Zapotec population. There were some subsequent uprisings against the new rulers, but for all intents and purposes, the Zapotecs were conquered. However, the seven Zapotec languages, and hundreds of Zapotec dialects, still survive with populations that have spread throughout Mexico and also Los Angeles, California.

Zapotec Writing and Religion

The Zapotecs developed a calendar and a logosyllabic system of writing that used a separate glyph to represent each of the syllables of the language. This writing system is thought to be one of the first writing systems of Mesoamerica and a predecessor of those developed by the Maya, Mixtec, and Aztec civilizations.

Like most Mesoamerican religious systems, the Zapotec religion was polytheistic. Two principal deities included Cocijo, the rain god (similar to the Aztec god Tlaloc), and Coquihani, the god of light. These deities, along with many others, centered around concepts of fertility and agriculture. It is likely that the Zapotec practiced human sacrifices to these gods of fertility, and also played elaborate and ritualistic ball games in the court at Monte Albán. They also practiced dedication rituals, which cleansed a new space. Fine pieces of rare jade, pearl, and obsidian were found in a cache in Oaxaca, and were probably used to cleanse religious sites or temples upon the completion of construction.

According to historic, as well as contemporary, Zapotec legends, their ancestors emerged from the earth or from caves, or turned into people from trees or jaguars. Their governing elite apparently believed that they descended from supernatural beings that lived among the clouds, and that upon death they would return to the same status. In fact, the name by which Zapotecs are known today results from this belief. The Zapotecs of the Central Valleys call themselves “Be’ena’ Za’a”—the Cloud People.

Mitla

Evidence of the central role of religion in the Zapotec cultural hierarchy is pronounced at the religious city of Mitla. It is the second most important archeological site in the state of Oaxaca, and the most important of the Zapotec culture. The site is located 44 kilometers from the city of Oaxaca. While Monte Albán was most important as the political center, Mitla was the main religious center, as evidenced by the elaborate buildings and artwork throughout the city. The name “Mitla” is derived from the Nahuatl name “Mictlán,” which was the place of the dead or underworld. Its Zapotec name is Lyobaa, which means “place of rest.” The name “Mictlán” was Hispanicized to “Mitla” by the Spanish.

What makes Mitla unique among Mesoamerican sites is the elaborate and intricate mosaic fretwork and geometric designs that cover tombs, panels, friezes, and even entire walls. These mosaics are made with small, finely cut and polished stone pieces, which have been fitted together without the use of mortar. No other site in Mexico has this.

Sources

- Boundless World History. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/world-history/textbooks/boundless-world-history-textbook/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike