6.3: The Mainland- Aristocracy Returns

- Page ID

- 135125

The Period of Division

The mainland saw many dynasties and would-be dynasties – those that did not even make it to a second generation – come and go. Many ruled only a small area. The convention of naming periods after the dynasties that governed “China” during a set of years, therefore, does not work well. Beginning in the tenth century, the term “Wei-Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties” was used to mean the years 220 to 589. Within that, “The Three Kingdoms” (CaoWei, Shu Han, and Wu) means 220-280. “Jin” means 265-420. “Six Dynasties” normally refers to southern regimes, 222 to 589, but sometimes to a different set of northern regimes. And so on. What is most productive is to think about their shared dynamics of state formation and disintegration, social change, cultural variation, and interactions among rulers.8

Just one more term: “The Sixteen Dynasties” refers to 23 mostly very short-lived regimes formed in various parts of the north and Sichuan between 304 and 439. They were founded by nine different ethnic groups. One example is the Ba state in Sichuan (304-349). The Ba people worshipped a tiger spirit, specialized in hunting and boating, and followed Celestial Master Daoism. Back in the Warring States period, they had had their own script.

But they adopted Chinese characters, spoke a variety of Chinese, fought for Liu Bang and Lu Exu in founding the Han dynasty, worked for the Han state as soldiers and officials; and then rebelled frequently in the Latter Han period, before founding their own state. Ba families took on different degrees of Han practices and beliefs. 9 The Ba are only one of the many groups on the mainland who moved in and out of independence, changing and intermarrying all the while.

The Northern Dynasties

As the Korean Three Kingdoms (Paekche, Silla and Koguryŏ) and Wa on the archipelago were learning how to control more people and territory, so on the mainland each dynasty tried out new ways to control land and labor. Both wealth-based class and violence-based domination increasingly cloaked themselves in hereditary rank. In contrast to Qin and Han times, people were increasingly born into a status in life they could not escape.

The Cao-Wei monarchy (220-265) was no more able than Han to end great-clan power and return to a Legalist-style meritocratic, bureaucratic state. So it invented new institutions that could provide the state with soldiers, grain and cloth, and personnel, while reinforcing clan landownership and power. First, on the military side, the Cao-Wei assured a supply of soldiers by making that occupation hereditary: a brother or son would replace each soldier or commander who died or could no longer fight. Military families were granted farmland, and permitted to marry only into other military families. Essentially, soldiers became a separate caste. This separation occurred even before the formation of warrior dynasties that sprang from the steppe.

Second, with respect to labor, the Cao-Wei state took over direct ownership of land that had been laid waste by war, or whose owners had fled or died. Landless people and war captives worked that land as tenants, paying rent directly to the government. Most Northern regimes both organized vast state plantations to tightly control the common people’s labor, and parceled out land and labor to officials. Beginning with the disarray of late Han, the great clans had been gathering refugees as their personal troops and dependents, sheltering them in fortified villages in exchange for half of the harvest. The central state of Cao-Wei, inheriting from Han, no longer had a direct relationship with these people; it could not count, let alone command them. Third, with respect to taxation, although Han had collected some taxes in money, repeated debasements and counterfeiting had undermined faith in copper coinage. So Cao-Wei taxed families on their wealth, stopped producing coins entirely, and assessed taxes in fine silk cloth. For centuries, silk would be used as money.

Fourth, to staff the government, the Cao-Wei continued to recruit men of good reputation and learning. But whereas in Han individual men recommended from localities were graded and posted by the center, now local inspectors graded men into nine ranks of quality. The power of some clans meant that rank, and even office, began again to become inherited. A man’s family determined his rank, and the upper ranks held the highest offices. Furthermore, noble families (shi 士, the old word for Zhou knights) were exempt from some taxes, as well as from labor for the state, and were legally superior to commoners (shu 庶). The Qin and Han equality under law was gone.

A century or so after Cao-Wei fell to Jin, a Xianbei clan established themselves as the Tuoba Wei or Northern Wei dynasty (386-534). They reunified north China as far as the Gansu corridor. Like Koguryŏ, Tuoba Wei moved its capital several times, and combined agriculture with hunting and herding; state herds had millions of head of sheep, horses, cattle and camels. Tuoba Wei herded people, too, relocating to their new capital near Datong in Shanxi a million people from Manchuria, the northern mainland, and the northern peninsula, including 100,000 skilled artisans. These war captives were granted to generals, officials, and aristocrats, and they and their children served in hereditary occupations as clerks, weavers and artisans, musicians and actors. The regime also succeeded in turning steppe clans into a loyal military caste. And it employed as officials the highly-educated members of the clans, experienced in governing.

But even Tuoba Wei could not control the clans’ estates. To try to turn the clans’ workers into taxpayers, Tuoba Wei eventually developed the “equal fields” system, parceling land out to farmers according to household labor power. The grain land could not be sold or inherited, but went back to the state when the household head died; land used for hemp or mulberry was not reclaimed by the state. Tax was collected in grain and hemp-cloth, and men were liable for military service. To expand the tax base, Tuoba Wei designated as many people as possible free commoners (labelled “respectable people” 良民) eligible for land grants, and restricted the category of “mean” or “base” people (賤民) to slaves, convicts, and their families. But since the regime could not really wrest control of land and labor away from the big clans, that only meant that the clans either dominated nominally free people and their land allocations, or claimed more allocations themselves on the basis of their labor power in the form of slaves and oxen. As free people moved to the wasteland the central state could really hand out, the big clans turned even more to slave labor. Owning and managing land themselves gave the elite a stake in producing knowledge about farming, such as an encyclopedia called Knowledge Needed by Ordinary People (Qimin yaoshu).10

The distinction between noble families and commoners, and increasingly fine distinctions among aristocratic ranks, became ever firmer in state practice and in elite thinking. (We don’t know what the non-elite thought.) Even when Dowager Empress Feng (r. 466-90), for instance, encouraged intermarriage among Xianbei nobility and nobility of the big clans dating back to Han times, she also required that people marry only into families of the same rank.11 Rank was real; ethnicity was changeable. The warrior and former-Han elite learned one another’s ways and languages, wrote poetry, studied the Classics, and practiced family ritual as well as warrior arts. The cultural convergence went too far for some soldiers’ taste, and a mutiny brought down the Wei, but it was replaced by other warrior regimes that also cooperated with the settled aristocracy. The connections of later northern dynasties reached even further: Empress Ashina of the Northern Zhou in the 560s may have been related to a wife of one of the Sassanid emperors of Persia about the same time, and to the later Empress Theodora, wife of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian II a century later.12

The Southern Dynasties

Although never able to control over land and labor to the degree that Qin and Han had done, the northern regimes did centralize more than those that conquered the south. The area below the Huai and Yangzi rivers had been lightly touched by Qin-Han governance. (“South of the River” or Jiangnan, which later referred to the area around the Yangzi delta, for Sima Qian in the Shiji meant “South of the Huai River,” 150 miles further north.) Where fertile wetlands abounded, rice farming had been combined with fishing, hunting, and foraging for wild foods. Southern groups varied widely in their family patterns, languages, religions, and degree of organization.13

When starvation, warfare, and disease slammed North China in the late Han period, millions of ordinary people fled south. Seizing land for farming, they pushed some of the original southerners up into the hills to scratch out a living. The Wu dynasty (222-280) forced other natives to serve as soldiers or tax-paying farmers. A second invasion of the South came when Xianbei and Xiongnu generals captured the old capitals of Chang’an in 306 and Luoyang five years later, pillaging and murdering. The Western Jin aristocratic clans fled south – perhaps 60% of the elite – accompanied by their many dependents, tenants, slaves, and servants, and whatever property they could carry. Heartily disdaining southern food, culture, language, and people, they planned to stay for only a while to keep alive the flame of true civilization: the written and ritual tradition of Zhou and Han.

But they stayed. And they changed. Initially, these northern refugees dominated the south, drawing on their experience in governance. But over time more locals learn to read and govern. Clan succeeded clan in a series of short-lived dynasties centered on today’s Nanjing. Living in a fertile land whose waterways provided some protection against cavalry from the north, the southern clans had little reason to give up power to a centralized state. This new aristocracy had little interest in restoring Qin/Han-style empire, but regarded the north as a foreign land. Historian Andrew Chittick has labelled the southern courts “the Jiankang Empire” to stress their full autonomy. As historian Hugh R. Clark writes, “North and south, in short, had gone separate ways. ‘China’ was not one.”14 The southern courts and clans focused on trade, and on deploying workers to clear, drain, and plant ever more land for rice agriculture.

Southern aristocrats did study the Classics and histories, and practice family ritual, like their northern counterparts. But they poured their energy into elegant conversation, literature, calligraphy, dance, music, and painting. Aristocrats made beautiful things themselves, and patronized artists and craftspeople. The surplus from riziculture commercialized luxury production. Around Hangzhou bay, paper was made, and hundreds of kilns produced beautiful ceramics. Artisans who designed and created bronze mirrors were so prized that some were recruited to migrate even to the archipelago. The Southern dynasties collected commercial taxes as traders from Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East carried goods back and forth from as far away as the Mediterranean. The largest port may have been near Hanoi. By 500, the southern capital housed over a million people. Aristocrats not only consolidated the social value of rank, but also benefitted from commerce. Wealth became less and less equally distributed.

Birds and Bears

At the level of high culture, much was shared across the mainland. But at the level of everyday life, variation was greater. Since ordinary people lived intimately with the elite as servants and nannies and wetnurses, they taught them their local stories, songs, languages, and foodways. Customs in cooking, clothing, song and dance, rituals of birth, marriage, and coming of age and the like have left little trace; the clearest place to see cultural divergence is in n burials, because archaeologists can find and examine tombs.

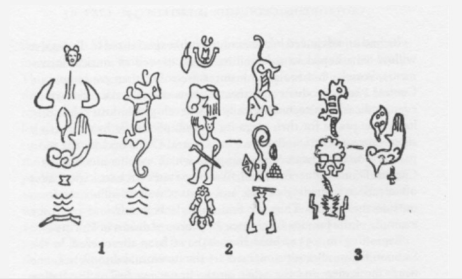

To give just one example of local culture, more than 200 pottery jars have been excavated from tombs in the Jiangnan area (roughly Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, around the mouth of the Yangzi River). Each one is unique, but share with features not found elsewhere. They have five mouths – a custom that developed in Han times (see Figure 6.2). But the Jiangnan jars from the period of division also flaunt many decorations. Supernatural animals on the jars include like dragons, the single-hearted double bird, the qilin, and others. Natural animals include dogs, sheep, turtles, monkeys, chickens, slugs, crabs, lions and others -- and lots of birds. Especially in Western Jin times, birds replaced most of the other animals (see Figure 6.3), except for what scholars have called bears. Scholars searching in the great written tradition have argued that the birds represent the human soul, flying up to heaven, but then why so many? And why do birds also appear on objects not made specifically for burial? And what about the bears?

Recently, historian Keith Knapp has interpreted the funerary jars in terms of local culture. Jiangnan legends tell that soon the first humans were starving. The gods ate rice, but they would not share it. Sparrows pitied people, stole rice from heaven, and brought it down to earth, and rats helped distribute it. Birds therefore symbolized grain, and fertility: childless couples would pray to the “God who Delivers Grain” and the husband would eat a male sparrow. The jars also include miniature imitation stone steles, saying things like: “Wealth and Happiness, may there be dukes and lords, many sons and grandsons, long life, and may there be no misfortune for a thousand hundred-thousand ten-thousand years.” The jars brought good luck for the living, so someone could tend the dead. Birds on funerary jars brought blessings in Jiangnan culture.15