6.4: The Peninsula and Archipelago Before Writing

- Page ID

- 135126

Prestige Objects and Power in the Three Kingdoms and Wa

In assessing interaction among people of different areas, archaeologists note the unique features of ordinary objects like clay storage jars and tiles. Styles and techniques change over time in one place, and vary from place to place. So, if a style of everyday pottery whose development can be traced in place A suddenly shows up in place B, we conclude that someone travelled from A to B. If that style develops further in B, we conclude that someone who knew how to make it settled in and taught others. Shared architectural features – styles of tombs and houses – indicate that people of different places are in direct contact through travel or immigration. Tomb styles are especially conservative, since the peaceful rest of the dead is at stake, so dramatic, permanent changes suggest that people have moved. Archaeologists also assume that when ritual objects develop in A, and then suddenly appear in B, the same rituals and the same meanings of the ritual have been carried by people from one place to another.16

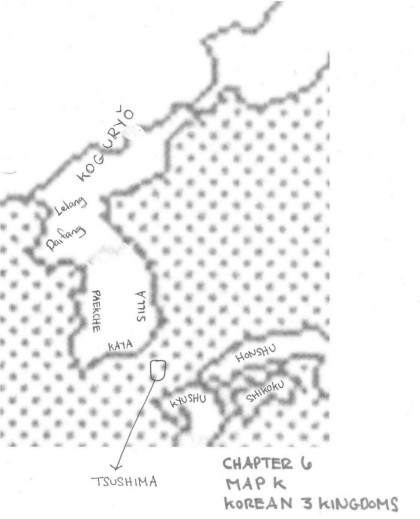

Luxury ceramics, and precious objects of bronze and gold, pass from hand to hand without migration. Their value – not only the material, but the great skill required to make such things – is so obvious that they can immediately signal status and power in new places. The rulers of the Korean Three Kingdoms (Koguryŏ, Paekche, and Silla), as well as the rulers of Kaya and Wa, increased their power by importing mainland culture and knowledge through trade; by monopolizing the increased production that iron made possible; by improving and multiplying bronze weapons, iron weapons, and iron tools; by displaying and distributing goods, whether made at home or imported, to increase their prestige and influence. We can easily understand how controlling weapons was useful in fighting other chiefs, or cowing farmers and workers. It takes a little more work to see how prestige goods like bronze mirrors created power.

East Asia did not have a commercial, money-based economy in which wealth translated directly into high social status (as we imagine our society today to be). Rather, prestige goods, often inherited or acquired as gifts or as booty, created a sense of awe. They indexed command of violence and resources, but particularly for those who did not know how to make precious objects, prestige goods may have signaled some extra-human power. The political order was always unstable, which is a fancy way of saying that chiefs gained and lost power. Even the rules of inheritance within one group were not fixed – certainly, patrilineal descent was not the rule. Therefore, to gain and maintain real and symbolic predominance, chiefs and kings relied on a constant stream of prestige goods, much as Xiongnu chief Modun had held his confederation together with a steady supply of tribute from the Han empire.

A canny leader would take control of a trade route, develop an alliance that could supply goods as gifts, seize goods from a neighbor by force of arms, or capture artisans who knew how to make things. He could pass those goods to his elite followers, who could pass some down to smaller chiefs below them. But each leader could be replaced; loyalty was temporary. The chiefs were not bureaucrats whom the top ruler closely controlled; if he gave them a gold-frilled crown to signify their authority that was all very well, but how could he take it back? To authorize a new chief, he would have to give him a new gold-frilled crown (or silver cap with comma-shaped jades, or whatever the current fashion in empowering headgear was).

Furthermore, both prestige goods and practical things like iron and armor were always being buried with chiefs and rulers. That is how we know about them, after all. The successor chief or ruler wanted to make a good show for the many visiting allies and subordinates whom archaeologists assume attended funerals. Power depended on displaying and sharing wealth, so no successor could afford a small, cheap tomb or a paltry assortment of grave goods: that would signal weakness. No matter how much the dead chief had amassed, the next one still needed a reliable supply. For instance, when Lelang and Daifang collapsed under attacks by Koguryŏ, Wa chiefs on in the area of southern Nara, who held the upper hand in the archipelago at that point, were cut off from their supply of Chinese prestige objects, including specific types of mirrors. That meant that they lost power to the clans in the Kinai region, who had suppliers from the Kumgwan Kaya state.

Bronze Mirrors and Gold Crowns

The most common sign of authority were bronze mirrors – disks cast so that they had decoration on one side and the other side was flat, and polished to reflect. Mirrors had originally been created in the steppe, and had spread to Shang. Thousands were cast in Han times, with patterns that incorporated wishes for longevity and prosperity, cosmological ideas about the five phases and five directions, and iconography of the cult of the Queen Mother of the West, as well as other themes. The Lelang commandery funneled bronze mirrors from the mainland to the Samhan and over to Kyushu in the archipelago. Eventually, craftsmen in the peninsula and archipelago produced them.

Hundreds of cast bronze mirrors have been excavated in the archipelago from Yayoiperiod and Tomb Period graves, sometimes a dozen or more arranged around the coffin. Mirrors imported from the mainland typically bear inscriptions of three kinds. How would you describe these types?

- [May you have] sons and grandsons for a long time!

[May you] live as long as metal and stone!

[May you] win high office!

Above, [may you] accord with the serried constellations; below, avoid misfortune. - Establishing Stability era, 7th year [AD 202], 9th month, 26th day. I made this bright mirror, refining pure bronze a hundred times.

- The court manufactory made this mirror; it has its own principle.

It fends off misfortune, and is fit to sell at market.

[Above] are the King Father of the East and Queen Mother of the West.

It lets You reflect yourself. May you have many descendants.

Mainland mirrors often used wrong characters that sounded the same, but when the mirrors were copied on the archipelago, the texts got even more interesting.

For instance, can you figure out what two changes happened, and why, to create the following inscription (translated into English), on two identical mirrors made in the archipelago?

I edam thgirb rorrim yrev lausunu evreserp snos dna snosdnarg htlaew tuohtiw timil erar†

Mirrors made in the archipelago also sometimes included meaningless, made-up characters, called “pseudo-inscriptions.” Lurie refers to all these kinds of inscriptions as “alegible,” meaning that legibility was not really their function. That is, most owners or viewers did not read the words, nor want to.17 Rather, like the mirrors themselves, characters were strange and interesting, and symbolized magical power or foreign connections.

As well as bronze mirrors, people liked gold. Plenty of it washed down in the streams of the peninsula; more gold ornaments have been found in Silla tombs and sites than in those of any other culture in the world. Archaeologists trace Silla’s alliances largely by finding their amazing gold crowns in tombs in Paekche and the archipelago.

Gold crowns made in Silla travelled as far west as Afghanistan. Their decorations of trees, deer, and birds suggest influences from Central Asia, while Silla earrings look like those of South Asian maritime cultures.18 Silla also used gold for horse-fittings like cheek-straps. During the periods of Silla-Wa alliance, gold crowns, necklaces, earrings, hair ornaments and finger rings; gilt-bronze saddle-frames, quivers, helmets with visors, and other kinds of armor and horse gear; iron ingots; and glass cups all travelled from Silla to Wa chiefs around Osaka and Nara. In return, Wa sent comma-shaped jade beads and soldiers who helped Silla push Koguryŏ away from the eastern coast.19 Silks,too, passed from ruler to rulers, in the form of banners declaring their titles, ribbons tied onto gold seals, or lengths of cloth to make into clothing.

Bronze, gold, and silk indexed power. If worked in exotic styles, they showed the subordinates of a ruler that he had access to wealth through trade or conquest, and if in local styles that he controlled the artisans who could make such things. When a king granted gold and bronze to lesser chiefs, they deployed it to impress those below them. Prestige objects created power through social processes; they did not merely symbolize it.

† Here’s the answer. 1. The inscription that was copied described the mirror as “unusual and rare,” but the person making the mold first left out the “rare” and then just stuck it in at the end. 2. The mold to cast the mirror was made without taking into account the reversal from right to left that would occur, so the characters are backward. See Lurie, Realms of Literacy, 60-61.

Iron and Chickens

On the mainland, bronze had been used for weapons, as well as ritual vessels, for over a thousand years before iron made its appearance. Bronze was practical, as well as symbolic. But in the peninsula, bronze made little impact until shortly before the arrival of iron, and the two metals arrived at about the same time in the archipelago, around 400 BC. Iron in ingots was a prestige good, buried in Samhan and Wa tombs. (The precise shape, style, and composition of iron ingots tells archaeologists where they were made.) As the northern dynasties used silk for currency, so iron ingots and tools served as money in the markets of the Samhan. But iron not only indexed power to create it socially; it also armed soldiers and fed them.

The centrality of iron appears in a story that the Silla kings had an ancestor who had worked as an iron-smelter, and who after death was worshipped as a smelting deity. But it was Kaya, in particular, that produced and traded enormous quantities of iron: enough to bury weapons and armor with rulers, and good enough to export even to the commanderies, which surely had access to iron made in the mainland. The iron trade was so important to Kaya that placement along trade routes – rather than, say, military strategic advantage or rich natural resources – determined which communities within the Kaya region rose to prominence.

Iron was not the only item that Samhan had to offer, of course. Samhan towns close to the coast became wealthy by exporting large chestnuts, fine-tailed chickens, grain, a few bronze items, and beautiful glass beads in blue and red, sometimes incorporating gold leaf. From the mainland they imported tin, horse-fittings, bronze mirrors, and other luxury goods. From about AD 200-300, the boat-savvy inhabitants of Tsushima, Iki, Okinoshima and other small islands took on the role of middlemen between Kyushu and the commanderies, and even the mainland proper. It is not clear what Wa exported in exchange for prestige goods and iron: probably local food items, and lumber, and perhaps manpower. Paekche King Muryong, for instance, had a fine coffin of Japanese pinewood.

This was not a question of domination. Both sides gained wealthy and prestige from exchanges. As time went on, the goods exchanged between the mainland and peninsula became more elaborate. Take Paekche as an example. Paekche sent a mission to whichever dynasty was ruling the southern mainland once every five to ten years from about AD 350 to 660. The missions were usually led by royalty or the descendants of mainlanders, accompanied by aristocrats. Twice, when the military situation was critical, crown princes went themselves. The missions asked for specific weapons; titles like “King of Paekche” and “Great General Pacifying the East” and garments showing those ranks; a specific divination text; skilled artisans; someone to teach the Book of Odes; commentaries on Buddhist sutras; and a master of ritual knowledge. In return, Paekche sent mainland regimes unspecified “local products,” and musicians – one group for the enthronement ceremony of a southern regimes, and more musicians for Sui. We know the connection was important to the southern regimes, because they granted titles to five Paekche kings even before missions arrived to request the kings’ investiture.

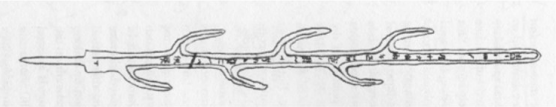

The connection with Paekche continued into Tang, still serving both sides. To the young Tang, King Mu of Paekche sent miniature horses called “under the fruit horses;” special, highly burnished iron armor; highly-decorated (in chasing) battle-axes; and a golden suit of armor (iron armor with gold lacquer) and more battle-axes. Tang Taizong was so pleased with King Mu’s gifts that he gave King Mu in return 3,000 pieces of silk and a special silk-brocade robe. When King Mu died in 641, Tang Taizong, upon receiving the embassy with the report, donned a white mourning robe, issued a eulogy in a public ceremony, and gave Mu a posthumous title. Paekche also sent gifts to the archipelago. Most astonishing is the Seven-Branched Sword sent to a Wa king in 369. A blade with no haft, about 2 feet long, it is held by a shrine in Nara. It was cleaned in 1874 (rather carelessly, so some words were lost from its hard-to-read gold-inlaid inscription.

In the fourth year of the Great Harmony era [AD 369], in the […] month, on the 16th day, the 43rd of the cycle, at noon, was made this seven-branched sword of multiply-refined iron. [May you] avoid injury in battle. It is suitable for a marquis or a king. […] made it. From ages past there has never before been a sword like this one. The Crown Prince of Paekche, Sagely Kusu, had it made especially for King Zhi of Wa. Pass it down and display it to later generations.20

More on inscribed swords later… But note here that the maker’s name was recorded, although it is now illegible. Such work was skilled, and those skills were recognized by rulers and warriors.

Boats and Storms

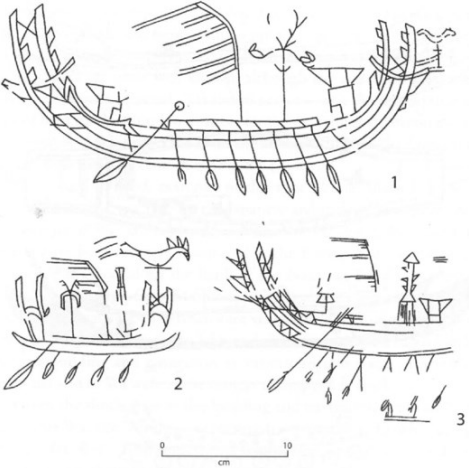

They did not record the names of the sailors, ordinary people doing the work of shuttling those prestige goods back and forth. Boats as presented by models and some drawings on Japanese haniwa (clay tomb figures) had oars for rowing, and maybe masts for sailing.

Sailors knew the routes and the ports, but the rocky coastline with its swirling currents could still be terrifying. One could not travel too far out or for too long, because the oarsmen needed to rest and eat. Setting out from northern Kyushu and its islets, Wa ships could first set anchor in Kaya to rest, resupply, and do a little trading; then stop at other places along the western coast of the peninsula; and finally make their way up the Kŭm River to the Paekche capital. Or Wa merchants and diplomats might change to a boat owned by Kaya or Paekche rulers or merchants along the way. At one Paekche harbor site dating to 400-600, archaeologists have found stone ritual tools of a kind used in ancestral worship in coastal Kyushu. Ships carrying Wa sailors or traders must have stopped there so they could offer prayers to their ancestors for a safe trip. We know even less about such folks than about their social superiors, who recorded their lives and values in their tombs.