10.16: Global vanguards

- Page ID

- 67855

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Global vanguards

Across the globe, new art traditions have responded to the radical changes of the 20th century.

1945 - present

Mexico

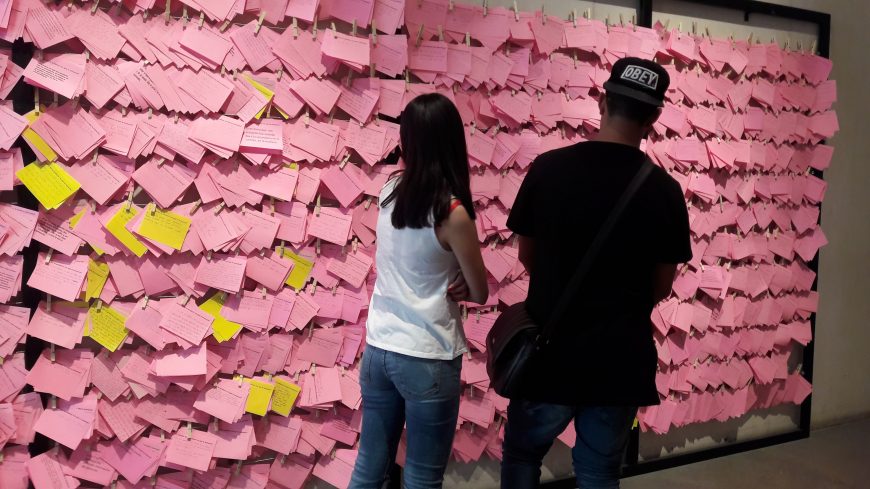

Mónica Mayer, The Clothesline

by DR. ALBERTO MCKELLIGAN HERNÁNDEZ

Hundreds of pink paper postcards

In 1978, artist Mónica Mayer distributed hundreds of pink paper postcards to a diverse group of women in Mexico City; each card included a statement that was meant to be completed by the participants: “As a woman, what I most hate about the city is.” Most of the completed responses highlighted experiences of sexual harassment within the urban environment of Mexico City. Mayer brought attention to the untold stories and silenced voices of urban women as her contribution to “New Tendencies,” an exhibition curated by Mathias Goeritz for the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City.

At the museum, the artist, who is from Mexico, presented the postcards held in place by clothespins hung from rows of pink string that were placed within a brightly-colored pink frame. By employing a color traditionally associated with femininity in multiple elements of the installation, Mayer underscored how her art project focused on women’s experiences, a topic often ignored by art institutions. The title of the installation, The Clothesline, deliberately referenced the domestic labor traditionally described as “women’s work” in Mexican society.

Several women visiting the exhibition wrote additional responses in the cards, spontaneously participating in the artistic process. Mayer’s installation — constructed out of simple materials — string, paper, and clothespins — shattered the silence that surrounded experiences of sexual violence in the city, allowing women to voice their experiences within the gallery spaces of the Museum of Modern Art. The hundreds of responses revealed how sexual violence was a large-scale social problem faced by women every day.

Intersections with Mexican feminism(s)

Mayer produced The Clothesline after participating in the burgeoning forms of feminist activism that flourished in Mexico City throughout the 1970s. This diverse social movement sought women’s emancipation in Mexican society, though individual activists and feminist organizations disagreed on how to achieve this goal. For instance, feminist groups debated whether they should cooperate with the Mexican government to change the country’s laws, or whether they should establish themselves as an independent movement that resisted any form of institutionalization.

Despite the different perspectives espoused by individual feminist organizations, several activists argued that the most pressing issues faced by contemporary women were sexual violence and reproductive rights. Members from different groups came together to establish the Coalition of Feminist Women in 1976 as a way to tackle these issues. Describing her participation in this coalition, Mayer noted the passionate debates that developed between activists: “violent discussions, radical attitudes, [and] painful recriminations were the norm.” Still, the artist also emphasized how these activists banded together to provoke social changes: “A wonderful memory I have from those days is the demonstration we held in front of the Senators Building in December of 1977, demanding the liberalization of abortion” [1]— underscoring the passion and diversity of feminist activism in Mexico.

Through The Clothesline, Mayer developed a participatory artistic installation that resonated with the issues raised by her fellow feminist activists. The project served as a prominent example of feminist art, since it encouraged audience members to question the ways in which gender inequality and sexual violence affected the individual lives of countless women. The collaborative methods Mayer employed in the production of the work also resonated with the egalitarian ideals of her fellow feminist activists. In a later description of the project, the artist argued that “the artwork is not the clothesline itself, but the interaction that occurs when you request responses and what happens when the public gets to read them.”[2] Mayer emphasized her position as both a creator and collaborator of the installation.

Transnational connections

After her participation in the exhibition, “New Tendencies,” Mayer continued exploring intersections between artistic practice and feminist activism. In 1978, she traveled to Los Angeles to study at the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW), the first independent center for feminist artistic instruction in the United States. Artist Judy Chicago, art historian Arlene Raven, and graphic designer Sheila de Bretteville established the FSW in 1973. The school was part of the larger Los Angeles based institution known as the Woman’s Building.

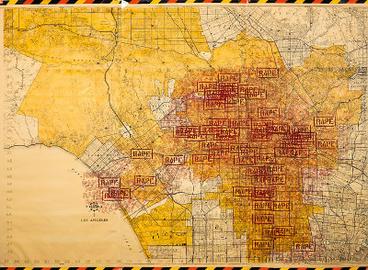

As a student at the FSW, Mayer found Suzanne Lacy’s artistic projects that explored the connections between public art, activism, and feminism particularly intriguing. In 1977, for instance, Lacy developed Three Weeks in May. As part of this project, the artist “went to the Los Angeles Police Department’s central office to obtain confidential rape reports from the previous day.”[3] Lacy then identified the locations of these crimes by stamping the word “RAPE” in a large-scale map of Los Angeles. The artist displayed this map at a public shopping center; she also presented a second map that showed the location of resource centers for women who had experienced sexual violence.

In Los Angeles, Mayer further considered the artistic potential of her clothesline installation. The Clothesline: Los Angeles emerged in 1979, when Communitas—a group from Ocean Park, Santa Monica—asked Lacy to explore the forms of violence experienced by women in that neighborhood. Lacy developed Making It Safe, a project in which “[s]he and her collaborators distributed leaflets, created a series of events, speak-outs on incest, small dialogues, and curated an art show in thirty windows of the local commercial district.”[4] As part of Making It Safe, Mayer redeployed her earlier clothesline project. As described by Mayer, the questions in this clothesline “revolved around the perceptions of safety and danger by women in the community of Ocean Park, including their proposals to feel safer.”[5]

By focusing the questions on the experiences of a particular community, the artist suggested how different geographic and cultural contexts shape the experiences of women. Instead of considering women as a monolithic group, the artist prompted participants to describe how living within Ocean Park shaped their understanding of violence and safety. Since both of the clotheslines alluded to the problem of sexual violence, the art project suggested how different communities of women, whether in Mexico City or Los Angeles, could establish alliances between them.

Legacy

Mayer’s clotheslines of the late 1970s are only a small glimpse of her extensive career as a feminist artist that has lasted for more than forty years. After her studies in the FSW, Mayer was a founding member of feminist art collectives such as Women Scribes and Portraitists and Black Hen Powder in Mexico City. The foundational project of The Clothesline continues to engage audiences throughout her home country and abroad. In the late 2010s, Mayer developed new versions of the project in Mexico City (2016), Washington, D.C. (2017), Hermosillo, Mexico (2018), Buenos Aires, Argentina (2018), and Portland, OR (2018). Each of these clotheslines reveal how Mayer challenges gender inequality across the globe, continuing the goals of social transformation espoused by Mexican feminist activists of the 1970s.

[1] Both quotes in this paragraph from Mónica Mayer, “On Life and Art as a Feminist,” N.Paradoxa Online, nos. 8-9. (2010), p. 49.

[3] “Three Weeks in May (1977),” accessed April 10, 2019, http://www.suzannelacy.com/three-weeks-in-may.

[4] “Making It Safe (1979),” Accessed April 10, 2019, http://www.suzannelacy.com/making-it-safe-1979.

[5] See Mónica Mayer, “El Tendedero L.A.,” De archivos y redes, November 23, 2015.

Additional resources:

Márgara Millán, “Traducción y política del feminismo mexicano contemporáneo,” in Cartografías del feminismo mexicano, 1970-2000, ed. Nora Nínive García, Márgara Millán, and Cynthia Pech (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, 2007).

Álvarez Romero, Ekaterina, ed. When in Doubt… Ask: A Retrocollective Exhibit of Mónica Mayer, (Mexico City: Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2016).

National Museum of Women in the Arts: The Clothesline Project

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Nigeria

Uche Okeke

“Young artists in a new nation, that is what we are! We must grow with the new Nigeria and work to satisfy her traditional love for art or perish with our colonial past.”

—Uche Okeke, from the “Zaria Art Society Manifesto,” Natural Synthesis, 1960

The Art Society of Zaria

During the period leading up to and following Nigerian independence in 1960, artists appropriated cultural and aesthetic traditions from around the country as a means of defining a new national identity. They drew upon narratives from Yoruba, Igbo, Urhobo and other cultures, Bible stories, local histories and artistic traditions to inform the content and style of their works, manipulating tales from the past to produce a mythology for the present.

This practice was defined as “natural synthesis” by the Art Society at Zaria, an arts group formed in the late 1950s by Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Simon Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya and other art students at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (now Ahmadu Bello University) at Zaria in the northern region of Nigeria. The Art Society sought to reconsider the emphasis on Western academic artistic traditions espoused by the largely European faculty at Zaria, an art program associated with Goldsmiths (part of the University of London). Moving away from traditions steeped in colonialism, “natural synthesis” merged the best of indigenous art traditions, forms and ideas with useful ones from Western cultures to create a uniquely Nigerian aesthetic perspective.

Later known as the Zaria Rebels, the members of the Art Society devised an academic program outside of the official university curriculum. The members thoroughly researched indigenous cultural and artistic traditions, produced works based on their findings and met regularly to discuss the outcomes. Though they took a similar conceptual approach to art making, the vast diversity inherent in the practices they analyzed led to great variation in their formal and stylistic synthesis.

The Uli aesthetic

Uche Okeke, the Art Society’s second president, drew inspiration for a new visual language from uli, an Igbo female body and wall painting tradition from southeastern Nigeria that is based on sinuous abstract forms derived from nature (above). In uli, Okeke saw “limitless expression,” internalizing the drawing technique he learned from his mother, a renowned uli draughtswoman, to serve a modernist sensibility.

While waiting in Abule Oje, Lagos in 1962 for traveling papers to Munich, Germany, where he was to train in stained glass and mosaic at the Franz Meyer Studio, Okeke created a series of pen and ink drawings that make up his remarkable Oja Suite. In one drawing, Owls (left), vertical lines, zigzags, spirals (agwolagwo or snake motif) and v-shapes (okala isinwaoji or three-lobed kola nut motif) come together to form two owls perched amidst dense foliage under a full moon. With his spare manipulation of line and spontaneous employment of uli symbols, Okeke distills cosmic and animal forms to their essential components. Okeke does not simply mimic uli forms but internalizes the flowing, poetic process of the drawing tradition itself, analyzing and exploiting its formal potential.

In drawings like Owls, the meanings of particular uli symbols become untied from their referents and depend entirely upon the other lines, motifs and spaces within the composition for interpretation. In Okeke’s hands, the flowing lines and naturalistic patterns of uli converge to form vegetal, human and animal compositions that give form the artist’s conception of a new Nigeria.

Civil war

After his return from Germany in 1963, Okeke settled in Enugu, then capital of Nigeria’s Eastern Region. With the help of other former Art Society artists, Okeke established a cultural center, which he directed from 1964 to 1967. Modeled on prominent scholar Ulli Beier’s Mbari Artists and Writers Club in Ibadan, Okeke’s Mbari Enugu brought together artists, writers, dramatists and intellectuals to exchange ideas, collaborate, exhibit and discuss new work.

From 1967 to 1970, Nigeria’s brutal civil war, known as the Nigerian-Biafran War, tore apart the newly independent nation with economic, ethnic, cultural and religious conflict. Though the southeastern provinces attempted secession to establish the short-lived Republic of Biafra, Nigeria remained largely united despite endemic corruption, poverty, inequality and injustice.

In the lead up to and during the war, Okeke mobilized participants at the Mbari to produce art, literature and performances that reflected their experiences of the conflict. With a heightened awareness of the failure, hope and tragedy of humanity, Okeke produced works like Refugee Family (1966) that meditated on the pogroms (organized massacres of particular ethnic groups) inflicted upon Igbo in Northern Nigeria at the start of the war. Alienated figures in earth tones are sparely outlined with thick uli-influenced strokes. The work’s modest medium (linocut on paper) and technique represent the artist’s need to process the conflict through visual production, despite the dearth of art materials available at the time.

Nsukka

After the war, Okeke joined the faculty of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he ran the Department of Fine and Applied Arts from 1971 to 1983. Under his direction, Nsukka rose to prominence as a center of Nigeria’s artistic creativity, drawing artists like the renowned El Anatsui to its ranks. At Nsukka, Okeke further developed his synthesis theory, encouraging students to research Nigerian art traditions to solve formal problems in their work. The artist’s own experiments with uli became increasingly abstract in prints like Isi Nwoji (1972) where uli motifs, like the diamond-shaped kola nut (isioji), are clearly defined but with a bolder graphic approach.

The oil boom of the mid-1970s expanded Nigeria’s income capacity, but also brought massive official corruption and the institution of a series of military regimes from 1983 to 1998. Under Okeke’s supervision, Nsukka students like Obiora Udechukwu manipulated uli, and later nsibidi, another indigenous graphic system, and even Chinese li calligraphy to give form to the social and political struggles preoccupying everyday life in Nigeria.

Through Udechukwu, who later became a prominent professor at Nsukka, Okeke’s rigorous intellectual inquiry into uli influenced another generation of artists, including Tayo Adenaike, Olu Oguibe, Chika Okeke-Agulu and Marcia Kure, among others. Like Okeke, these artists continue to think deeply about place and history in their very contemporary manipulations of design traditions from the past.

Additional Resources:

“The Poetics of Line: Seven Artists of the Nsukka Group,” National Museum of African Art

Ulli Beier, Contemporary Art in Africa (London: Pall Mall Press, 1968).

Clementine Deliss, Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa (New York: Flammarion, 1995).

C. Krydz Ikwuemesi, ed. The Triumph of a Vision: An Anthology on Uche Okeke and Modern Art in Nigeria (Lagos: Pendulum Art Gallery, 2003).

Chika Okeke-Agulu, “Nationalism and Rhetoric of Modernism in Nigeria: The Art of Uche Okeke and Demas Nwoko, 1960-1968,” African Arts, vol. 39, no. 1 (Spring 2006): pp. 26-37, 92-3.

Simon Ottenberg, New Traditions from Nigeria: Seven Artists of the Nsukka Group (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997).

Simon Ottenberg, ed. The Nsukka Artists and Nigerian Contemporary Art (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of African Art and University of Washington Press, 2002).

Sudan

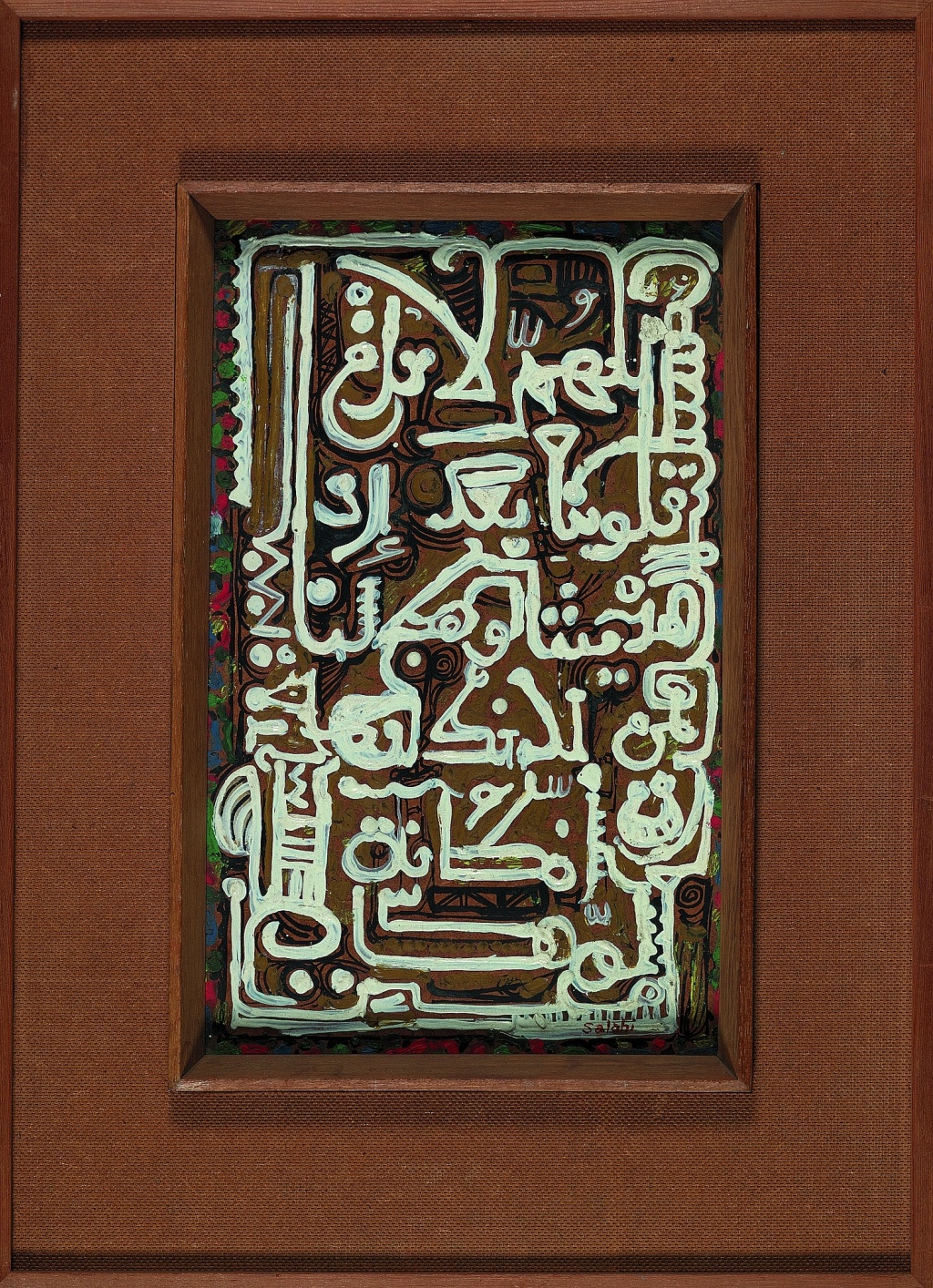

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams

How would you paint a picture of something that’s not quite representable… like the sound of voices chanting, a spiritual vision, a childhood memory, or a dream that you can’t remember?

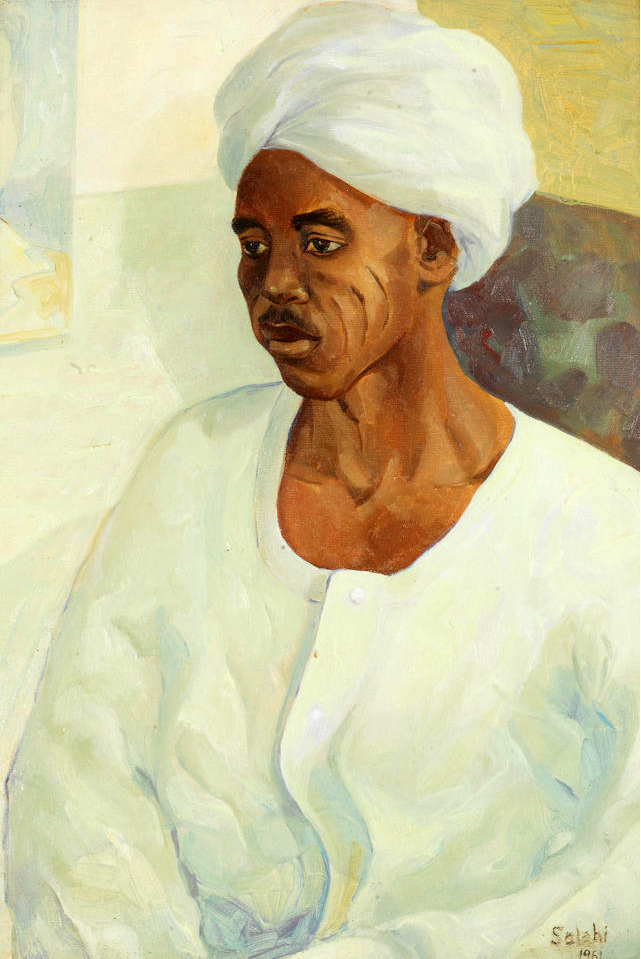

In his painting Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams, the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi creates a masterful and haunting scene inspired by just these types of experiences.

A group of harrowing, evanescent figures approaches the viewer, some occupying the full height of the canvas. Their limbs are elongated and skeletal, and their mask-like faces are accented by hollow, circular eyes. Upturned crescent shapes sit atop their heads, reminiscent of bull’s horns or celestial symbols, giving them a sense of timeless power. Yet, the figures’ lower bodies seem to gradually fade into the background, transforming into abstract shapes like circles, lines, and hooks. Along the lower register, atmospheric mists of sandy and ashen tones disturb the limits of the figures’ outer contours—and all depicted forms seem to move fluidly between positive and negative space. Our eyes begin to deceive us: Are these creatures human, animal, or spirit?

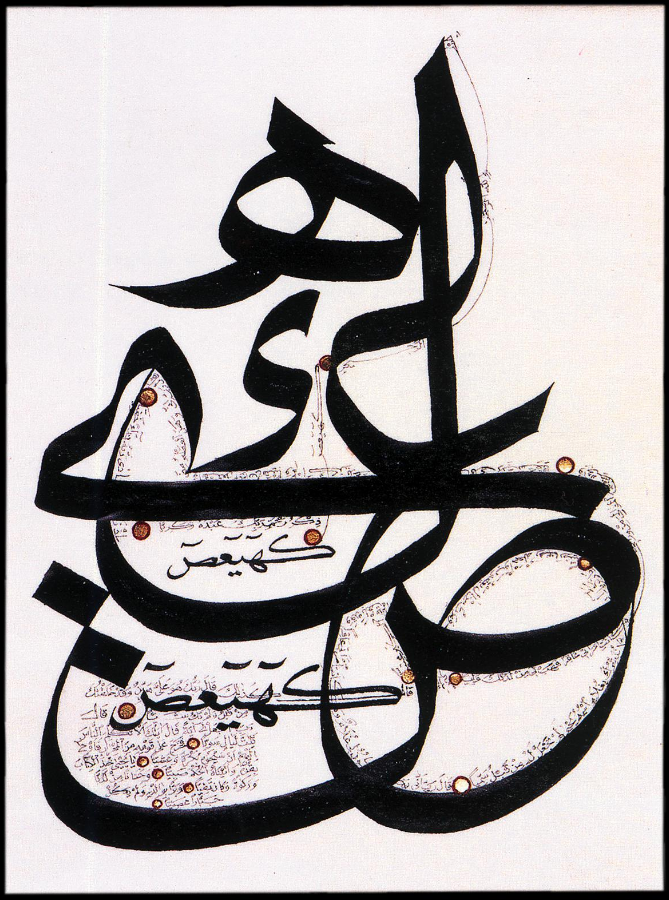

This piece is typical of the artist’s work from the early-to-mid 1960s. El-Salahi uses an earthy color palette that invokes the region’s natural environment, and blends elements of modernist abstraction with a number of motifs drawn from the breadth of Sudanese cultural histories: the elegance of Arabic calligraphy, the attenuated forms of sub-Saharan figural sculpture, and aspects of ancient Nubian art. As such, it is also exemplary of the wider genre of postcolonial Modernism; created during the years in which many African countries gained independence from oppressive colonial regimes, it reflects a new articulation of African identity as being markedly global, and defiantly modern.

From Western realism to calligraphic abstraction

Born in 1930 in Omdurman, Sudan, El-Salahi’s initial artistic development was informed by his training under the British colonial system. He began his studies in 1949 as a painting major at Khartoum’s Gordon Memorial College, which offered a Western academic curriculum, before leaving his home country to attend the Slade School of Fine Art in London in the mid-1950s. There, he excelled in creating realistic portraits and landscape studies. It was during his time abroad that Sudan sought and gained its independence from the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, an alliance between Egypt and the British Empire that had asserted political control over the region since the late 19th century.

When he returned to Sudan in 1957, El-Salahi suddenly found himself feeling disconnected from his home country. He realized that his Western training had alienated him from the concerns and visual expressions of the community he grew up in. As he later reflected:

[T]his radically changed attitude, the attitude of an extravagant, conceited young artist fresh from London, actually just hemmed me in. Over time, I came to see that conditions in Sudan required a very different approach on the part of the artist, who would otherwise be completely isolated from his audience. If I was to have a relationship with an audience, I had to examine the Sudanese environment, identify what it offered, assess its potential as an artistic resource and explore its possibilities as a complementary element in artistic creation. [1]

The artist began to experiment with a style of calligraphic abstraction that was, at the time, associated with the work of pioneering Sudanese artist Osman Waqialla. A leading figure in what would loosely become known as the Khartoum School, Waqialla was fascinated by the formal properties of calligraphic writing—its balancing of lights and darks, positive and negative space, and the lyrical motion of sweeping, interconnected strokes. He and his pupils worked to detatch the aesthetic components of calligraphic text from the sacred connotations it often carried, making reference instead to secular works of contemporary poetry.

Similarly captivated by Arabic lettering, El-Salahi undertook a rigorous study of its visual elements. Eventually, he liberated the written text from its semiotic meaning: “I squeezed letters and decorative units into a narrow, limited space within the overall pictorial field. The letter became legible, yet abstract,” he reflected. “Later I considered separating the calligraphic symbol from its verbal representation, so that what was read referred only to the letter form and nothing else.” [2] In a number of early works, El-Salahi inventively transformed written marks into entangled webs of lines and curves.

Adopting a subdued and somber color palette that is representative of the desert landscape of northern Sudan, the artist would gradually expand his experimentation to include art forms beyond Arabic calligraphy. The lines and hooks, associated with kufic writing, soon morphed into other forms: ghostly figures, animals, and vegetal motifs came to populate his compositions, as well as concentric linear patterns that the artist associated with sonic waves. In one of his most abstract canvases from this period, The Last Sound (1964) he represents the Islamic prayers for the dying, which accompany the soul’s passage between life and death.

Postcolonial modernism

El-Salahi’s work should be situated within the broader history of postcolonial Modernism in Africa. Throughout the 1960s, creative practitioners from across the continent and its diasporas produced radical innovations in art, literature, music and theatre. They wanted their art to reflect the cultural and political transformations that were sweeping the continent as it was liberated from colonial rule. Many looked to fuse modernist Western styles (to which they had been exposed through school or travel) with pre-colonial African visual forms. This essay on Uche Okeke, for instance, chronicles the influence of Igbo aesthetics on Nigerian art of the same period.

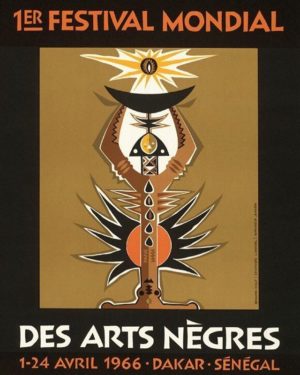

In the early 1960s, El-Salahi took part in a transnational workshop called the Mbari Artists and Writers Club. Located in Ibadan, Nigeria, it was run by the German expatriate Ulli Beier, and brought together artists and writers like Uche Okeke, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Jacob Lawrence, and many others. El-Salahi also participated in landmark events of the Pan-Africanist movement, such as the 1966 First World Festival of Black Arts (Premier festival Mondial des arts nègres) in Dakar, Senegal, where artists, dancers and musicians from across the African diaspora gathered to express pride in Black artistic and cultural expression.

“The Jungle and The Desert”

In his unique interpretation of postcolonial Modernism, El-Salahi tapped into the diverse cultural history of Sudan and its surrounding regions. His home country saw the birth of the ancient Nubian civilization, later encountered by the Egyptian, Ptolemaic Greek and Roman Empires. It was also a crucial juncture in the early history of Christianity and the expansion of Islam.

When El-Salahi was growing up, the national borders of Sudan encompassed both the North (which is predominantly Islamic and culturally Arab) as well as the sub-Saharan South (largely inhabited by the Dinka and Nuer peoples). El-Salahi’s interest in this diverse artistic legacy is mirrored by the parallel evolution of a literary and poetic movement, The Jungle and Desert School (Madrasat al-Ghaba wa al-Sahra), whose writers also drew inspiration from both African and Arab sources. Unfortunately, long-standing religious and economic rifts between each of these contingencies have led to a series of violent civil wars across the region in recent decades, and the nation has since been divided following the secession of South Sudan in 2011.

El-Salahi’s style is, ultimately, expressive of his uniquely personal vision. Spiritual visions, childhood dreams, and sonic memories infuse his work with a haunting, elegiac quality that masterfully interweaves cross-cultural sources and personal experiences. As the artist stated,

[T]he work of art is but a springboard for the individual intellect, or is like a reflecting mirror bring us back to our own selves. The picture floats freely within the realm of a simple relationship between viewer and form, an invitation to visual meditation and to a better knowledge of the self. [3]

Notes:

- Ibrahim El-Salahi, “The Artist in His Own Words,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, ed. Salah Hassan, Museum for African Art, New York (2012): p. 84.

- Ibid., p. 88.

- Ibid., p. 91.

Korea

Song Su-Nam, Summer Trees

Modern, but deeply rooted in tradition

In Song Su-nam’s Summer Trees, broad, vertical parallel brush strokes of ink blend and bleed from one to the other in a stark palette of velvety blacks and diluted grays. The feathery edges of some reveal them to be pale washes applied to very wet paper, while the darkest appear as streaks that show both ink and paper were nearly dry. The forms overlap and stop just short of the bottom edge of the paper, suggesting a sense of shallow space—though one that would be difficult to enter. Only a practiced hand could control ink with such simplicity and impact. The painting exudes psychological power, despite its relatively modest proportions (it is only a little more than 2 feet high).

Song’s exploration of tone (the shades of black and gray) and the effects produced by the marks of the brush, the wet paper, and dripping ink, has led some to think that these abstract, formal qualities are the real subject of this very modern-looking work. But it is important that the title refers to the natural world. Song created Summer Treesin 1979, but he made at least two similar paintings. One, in 1986, he called Tree (below). Not until the second, painted in 2000, did he fully embrace abstraction by leaving the work untitled. His title—and even his decision to create a work in ink—shows us that though clearly addressing issues of contemporary art—Song’s work is deeply rooted in tradition.

Ink

To choose the medium of ink on paper was important for the artist‚ a leader of Korea’s “Sumukhwa” or Oriental Ink Movement of the 1980s. Sumukwha is the Korean pronunciation of the Chinese word for “ink wash painting,” also called “literati painting.” The “literatus” can be defined as a “scholar-poet” or “scholar-artist,” a type of ideal man that emerged in China in the 11th century or before. Chinese poetry was considered the noblest art and “ink wash painting” was its twin, because writing a poem and making a painting used the same tools and techniques—one resulting in words, the other a picture. In their simplicity and reductiveness, the style of ink wash paintings created centuries ago often seem to match Western notions of abstraction (left).

In Chinese poetry, mountainous landscapes and the plants that grow in them serve as metaphors for the ideal qualities of the literatus himself—qualities such as loyalty, intelligence, spirituality, and strength in adversity. The world the literatus wants to live in is one of beauty, deep in nature, away from the centers of power and money. These themes provided painters with a library of motifs. From the 1970s–90s, Song created many such landscapes, executed unconventionally, with and without titles. Summer Trees may also reference a traditional theme: a group of pine trees can symbolize a gathering of friends of upright character. Whatever his intention with this title, Song was clearly alluding to the special world of the literati. Highly educated and a respected professor, he stood among the modern literati of Korea.

A Korean identity

Song’s interest in abstraction and the formal properties of ink has led some art historians to attribute the inspiration for his work to that of American artists like Morris Louis who used the medium of acrylic resin on canvas in his “Stripe” paintings of the 1960s, which resemble Song’s works of later decades such as Summer Trees. But in Korea during the 1980s there was a tension between the influence of Western art that used oil paint (whether traditional or contemporary in style), and traditional Korean art that used an East Asian style, the vocabulary of traditional motifs, and the medium of ink for calligraphy and painting. Song felt very strongly that the materials and styles of Western art did not express his identity as a Korean.

Sumukwha provided Song and his circle with a way to express Korean identity. Since antiquity, the country had taken great pride in a political and cultural distinctiveness that was recognized throughout Asia. Yet the twentieth century had brought humiliating trauma: the end of Korea’s ancient monarchy, colonization by the Japanese who had attempted to obliterate the Korean language, mass destruction during the Korean War (1950-53), and the partitioning of the nation. In South Korea, where Song lived, the country was healing but endured authoritarian government and student unrest. People lived in constant fear of hostility from North Korea. For protection, they accepted a conspicuous American military presence, but this cast modernization in a decidedly Westernized light.

Sumukwha’s ideal—the literatus—presented a compelling antidote to the psychological displacement felt by Song’s circle of artists and intellectuals: a model individual of character and moral compass no matter what challenges life presents; and a way of expressing those ideals through his iconic tools of ink and brush. Summer Trees, with its allusions to friendship and a balmy season, could be Song’s statement of optimism in the rediscovery of traditional values recast for modern times.

Additional resources:

Song’s work at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Special Exhibition of Donated Works: Song Soo-nam at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Park Soo-mee. “Artist’s Willingness to Experiment with Korean Ink Bent Boundaries” Korea JoongAng Daily,February 26, 2004

Kim Seong-Heui, translated by Seung Il Oh, “On the Basis of Art Educational Implications”

Joan Kee, “The Curious Case of Contemporary Ink Painting” Art Journal, vol. 69, no. 3, 2010, pp. 88 – 113.

Lee Kyeung-sung. “Song Su-nam: The Ink Images Expanding Into Infinity,” exhibition of Song Su-nam, Center for Korean Studies, University of Hawaii, March 1 – 17, 1980.

Francis Mullany, Symbolism in Korean Brush Painting (Kent: Global Oriental 2006)

Jane Portal, Korea, Art and Archaeology (London: The British Museum Press, 2000)

China

Liu Chunhua, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan

by DR. KRISTEN CHIEM

Striding atop a mountain peak wearing a look of determination on his face, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan shows a young Mao Zedong (Chinese Communist revolutionary, founding father of the People’s Republic of China, and leader of China from 1949-76) ready to weather any storm. In picturing a moment in Chinese Communist Party history, Liu Chunhua celebrated Chairman Mao (then in his seventies) and his longstanding commitment to Communist Party ideals. Painted in 1967 at the dawn of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, this work uses socialist realism to portray Chairman Mao as a revolutionary leader committed to championing the common people.

Socialist realism and Mao paintings

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), artists focused on creating portraits of Mao, or “Mao paintings,” which represented Mao’s effort to regain his hold after bitter political struggles within the party. With the leadership of Mao’s last wife, Jiang Qing, the movement aimed to quell criticisms of Mao in drama, literature, and the visual arts. More broadly, it aimed to correct political fallout from the disasters of the 1950s, especially the widespread famine and deaths that resulted from the Great Leap Forward (an attempt from 1958–61 to rapidly modernize China, transforming it from an agrarian economy into an industrialized, socialist society), and reinvigorate Communist ideology in general. In the years that followed, Mao would lead the country through a decade of violent class struggles aimed at purging traditional customs and capitalism from Chinese society.

In the early years of the Cultural Revolution, artists such as Liu Chunhua turned to a style known as socialist realism for creating portraits of Mao Zedong. Socialist realism was introduced to China in the 1950s in order to address the lives of the working class. Suitable for propaganda, socialist realism aimed for clear, intelligible subjects and emotionally moving themes. Subjects often included peasants, soldiers, and workers—all of whom represented the central concern of Mao Zedong and the Communist Party. Modeled after works in the Soviet Union, paintings in this style were rendered in oil on canvas. They notably departed from Chinese hanging scrolls in ink and paper, such as Li Keran’s Ten Thousand Crimson Hills, painted in 1964 (left).

Standardized by the Central Propaganda Department, Mao paintings typically pictured the Chinese leader in an idealized fashion, as a luminous presence at the center of the composition. Unlike Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, portraits usually depicted Mao among the people, such as strolling through lush fields alongside smiling peasants.

The Anyuan Miners’ Strike of 1922

Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan presents a critical moment in Chinese Communist Party history: Mao marching toward the coal mines of Anyuan, Jiangxi province in south-central China, where he was instrumental in organizing a nonviolent strike of thirteen thousand miners and railway workers. Occurring only a year after the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, the Anyuan Miners’ Strike of 1922 was a defining moment for the Chinese Communist Party because the miners represented the suffering of the masses at the heart of the revolutionary cause. Many of the miners enlisted as soldiers in the Red Army (the army of the Chinese Communist Party), intent on following the young Mao toward revolution.

Painting nearly half a century after the Anyuan Miners’ Strike, Liu Chunhua created Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan for a national exhibition. Liu Chunhua was a member of the Red Guard, or the group of radical youth whose mission was to attack the “four olds” (customs, habits, culture, and thinking). To create this painting, he studied old photographs of Mao and visited Anyuan to interview workers for visual veracity. Based on his findings, he rendered Mao wearing a traditional Chinese gown rather than Western attire, which is more commonly seen in portraits of Mao created during the Cultural Revolution. The cool color tonalities of Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan also differ from other Mao paintings, which tended toward warm tones with clear, blue skies, such as Chen Yanning’s Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside (below). Others often featured vibrant red accents—red being the color of revolution. Instead, Liu Chunhua opted for deep blue and purple hues to capture Mao’s determination as he marched to address the plight of those suffering.

In Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, Liu Chunhua adapted Chinese landscape conventions to a new style and purpose—an evocative portrayal that suggested that Mao was capable of leading the country toward revolution. He pictured his subject emerging atop a mountain with clouds of mist below. In China, landscapes such as this often evoked immortal realms, or extraordinary sites invested with the misty vapors of the mountain. However, a telephone pole is discernable in the lower left corner of the composition, and water cascades from a dam in the right—hints of modernity within the ethereal landscape. With an umbrella tucked beneath one arm and the other hand clenched into a fist, and wearing windswept robes, Mao appears superhuman, yet also practical and charismatic.

As a prominent icon in the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan celebrated the grassroots nature of revolutionary history and cultivated devotion to Mao during a tumultuous time. As a brilliant example of Chinese Communist Party propaganda, it was reportedly reproduced over nine hundred million times, and distributed widely in print, sculpture, and other media.

Additional resources:

This painting on Art Through Time

Melissa Chiu and Zheng Shengtian, Art and China’s Revolution (New York: Asia Society, 2008).

Elizabeth J. Perry, Anyuan Mining China’s Revolutionary Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).