10.15: Post-Minimalism

- Page ID

- 67854

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Post-Minimalism

Minimalism and Conceptual Art opened the way for a variety of experimental practices in different media.

c. 1965 - 1980

Louise Bourgeois, Cumul I

by KAREN SCHIFMAN

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Louise Bourgeois, Cumul I, 1969, white marble on wood base, 51 x 127 x 122 cm (Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris) © Estate of the artist (photo: Strifu, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Reality of Three-Dimensional Form

Bulbous mounds, and spherical or oval growths emerge, conflate and disturb. Cumul I is a marble sculpture, part of a series, by the late French-born artist, Louise Bourgeois. Cumul, as in, cumulus, is a reference to the forms of rounded clouds. The motif was first developed in drawings but Bourgeois wanted the reality of three-dimensional form, as she thought she could express deeper things in sculpture.

Like so much of Bourgeois’ work, Cumul I is loaded with entangled metaphors of male and female body parts that are simultaneously abstract and descriptive. Her career breezed over so many significant trends of the 20th century that her work defies identification within any single art movement. Instead, there is an uncompromising personal symbolism throughout her oeuvre (life’s work), filled with certain recurring motifs such as vessels, containers, ovoids, body parts, and spiders (a metaphor of her mother’s work as a weaver).

Appealing and Disturbing

The sculpture, Cumul I, is designed to sit on the floor and be viewed from above. Its forms still shock nearly half a century after its completion. The artist denied any reference to sexual forms in this work, but the association is undeniable. The viewer is confronted with a cluster of mounds that resemble breasts and penises emerging from a rippling fabric. So what then was Bourgeois trying to communicate in this beautifully sculpted marble? What can be understood from a sculpture that is aesthetically appealing and at the same time disturbing?

Bourgeois offered some explanation to her mysterious oeuvre and implied that the Freudian concept of a traumatized childhood was the catalyst for her artistic motives. The artist has confirmed that all of her work found inspiration in her childhood. Scholars have noted that the childhood traumas of having a sick mother and egocentric philandering father who had an affair with her nanny, had a powerful impact on the young Bourgeois who later stated, “My childhood has never lost its magic, it has never lost its mystery, and it has never lost its drama.”1 References to Bourgeois’ family, and sexuality, developed over the span of her career into a personal artistic vocabulary.

Making Sense of Cumul I

When we try to make sense of the male and female forms that reveal and conceal themselves simultaneously in Cumul I, it can help to remember Bourgeois’ childhood. Ambiguity and overlapping gender are characteristics found in many of Bourgeois’ sculptures and installations. Her art is deeply personal, confusing, troubling, magical and quite wonderful. She was one of the most significant women artists of the twentieth century.

1. Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father Reconstruction of the Father, Writings and Interviews 1923-1997, edited and with texts by Marie Laure-Bernadac and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, MIT Press, 1998, page 277. The quote is also found in a compilation of Bourgeois’ images juxtaposed by text entitled “Album” 1994 and published by Peter Blum.

Additional Resources:

This sculpture at the Centre Pompidou

Video of Louise Bourgeois’s Confrontation at the Guggenhiem Museum, 1978

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party

by DR. JENNIE KLEIN

A Place at the Table

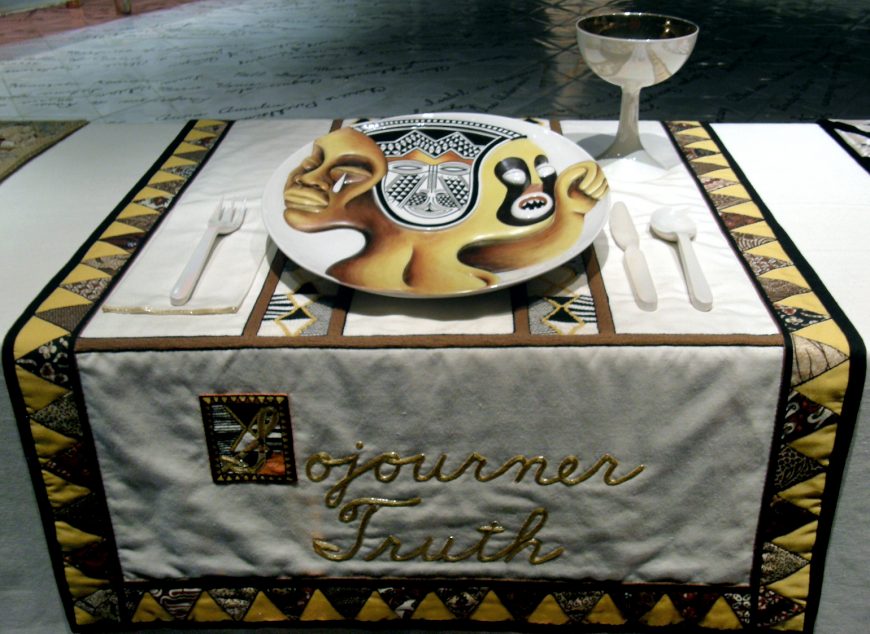

The Dinner Party is a monument to women’s history and accomplishments. It is a massive triangular table—measuring 48 feet on each side—with thirty-nine place settings dedicated to prominent women throughout history and an additional 999 names are inscribed on the table’s glazed porcelain brick base. This tribute to women, which includes individual place settings for such luminary figures as the Primordial Goddess, Ishtar, Hatshepsut, Theodora, Artemesia Gentileschi, Sacajawea, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Emily Dickinson, Margaret Sanger, and Georgia O’Keeffe, is beautifully crafted. Each place setting has an exquisitely embroidered table runner that includes the name of the woman, utensils, a goblet, and a plate.

The Dinner Party was intended to be exhibited in a large, darkened, sanctuary-like room, with each place setting individually lit, making it look as though it is composed of thirty-nine altars. The 999 names, written in gold, gleam softly, suggesting a hallowed or liminal space. Five years in the making (1974-1979) and the product of the volunteer labor of more than 400 people, The Dinner Party is a testament to the power of feminist vision and artistic collaboration. It was also a testament to Chicago’s ability to create a work of art that spoke to people who had not previously been a part of the art world. When the exhibition opened at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco in March of 1979, it was mobbed. Judy Chicago’s accompanying lecture was completely sold out.

Although critics praised the table runners, they ignored or disparaged the plates. These ceramic objects, which become increasingly three-dimensional during the procession from prehistory to the present in order to represent women rising, look somewhat like flowers and butterflies. They also resemble female genitalia, which many people found disturbing. Writing for the feminist journal Frontiers in 1981, Lolette Kuby was so taken aback by the plates’ forms that she suggested that Playboy and Penthouse had done more to promote the beauty of female anatomy than The Dinner Party ever could.

Kuby’s distaste for pudenda was echoed more forcefully a decade later, when Chicago attempted to donate the artwork to the University of the District of Columbia. Chicago was forced to withdraw her donation after the U.S. Senate threatened to withhold funding from UDC if they accepted what Rep. Robert Dornan characterized as “3-D ceramic pornography” and Rep. Dana Rohrabacher dismissed as a “spectacle of weird art, weird feminist art at that.” It was not until 2007 that The Dinner Party, an icon of feminist art, would find a permanent home in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Feminist Education

What drove Chicago to embark on such a large and controversial feminist project? She was inspired, in part, by her pioneering work in feminist education. She started the Feminist Art Program at California State University, Fresno in 1970. The following year she founded the Feminist Art Program (FAP) at the newly established California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) with the abstract painter Miriam Schapiro. The galleries were still under construction when Chicago arrived at CalArts, so the FAP had their exhibition in an abandoned mansion that was slated to be demolished shortly after. The resulting installation, Womanhouse, was a testament to Chicago’s method of teaching, which begin with consciousness raising and then progressed to realizing a message through whatever medium was most suitable, whether it was performance, sculpture, or painting.

While at CalArts, Chicago and Schapiro developed the idea of “central core imagery,” arguing in a 1973 article published in Womanspace Journal that many women artists making abstract art unconsciously gravitated towards imagery that was anti-phallic. By the time she began working on The Dinner Party, Chicago had come to believe that central core imagery, which celebrated feminine eroticism and fertility, could be used to challenge patriarchal constructions of women. For Chicago, there existed an irreducible difference between men and women, and that difference began with the genitals. Chicago would eventually put vaginal imagery front and center in The Dinner Party.

Right Out of History

After several years of work establishing various feminist art programs in Southern California, Chicago was eager to get back to making her own artwork and resigned from teaching in 1974. Her experience with Womanhouse inspired her to embrace materials that had traditionally been associated with women’s crafts, such as embroidery, weaving, and china painting. She was determined to make a monument to women’s history using china-painted plates alluding to thirteen specific figures, which she originally planned to hang on the gallery wall. However, she soon realized that there were many more women that she wished to include, and the initial conception of the piece expanded to a large-scale installation with thirty-nine place settings.

An important component of the piece was the educational material that represented the years of research that had been conducted by Chicago’s volunteer staff, led by art historian Diane Gelon. The Dinner Party was accompanied by a book of the same title (published by Anchor Books in 1979 and designed by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville) that included the stories behind all 1,038 names. Filmmaker Johanna Demetrakas documented the monumental effort that it took to make this installation in her film Right Out of History: The Making of the Dinner Party.

Not Exactly Playboy or Penthouse

In order to understand The Dinner Party, we must keep in mind that the sculptural painted plates were intended to be metaphors rather than realistic representations. Take, for instance, the final place setting on the table—the one for Georgia O’Keeffe. This plate is the most sculptural piece in the installation. Pink and greenish gray swirls and folds radiate out from a central core framed by fleshy looking folds that seem to have been deliberately spread apart in order to reveal what should be a hidden entrance. The plate can be read as suggestive of female genitalia, but its forms also recall the shape of a butterfly and the reproductive organs of flowers. O’Keeffe was famous for her abstracted paintings of flowers, and and the plate is an homage to some her best-known works, such as Grey Lines With Black, Blue, and Yellow (1923) and Black Iris III (1926), both of which have a central opening framed by folds, or Two Calla Lilies On Pink (1928), which has a similar color palette to the O’Keeffe plate.

Chicago’s decision to use vaginal imagery has proven to be powerful. The Dinner Party, having survived rejection, critical dismissal, and political grandstanding, is now considered a key work of contemporary art, and is permanently installed in a dedicated space at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.

Additional Resources:

The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago at the Brooklyn Museum

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party: Restoring Women to History (Arnold L. Lehman, foreword. Brooklyn Museum of Art/The Monacelli Press, 2014).

Jane Gerhard, The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the Power of Popular Feminism, 1970-2007 (Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 2013).

Gail Levin, Becoming Judy Chicago (New York: Harmony Books. 2007).

Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse, Untitled (Rope Piece)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Eva Hesse, Untitled (Rope Piece), 1970, rope, latex, string, wire, variable dimensions (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York)

Eva Hesse, Untitled

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Eva Hesse, Untitled, 1966 , enamel paint, string, papier-mâché, elastic cord (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF)

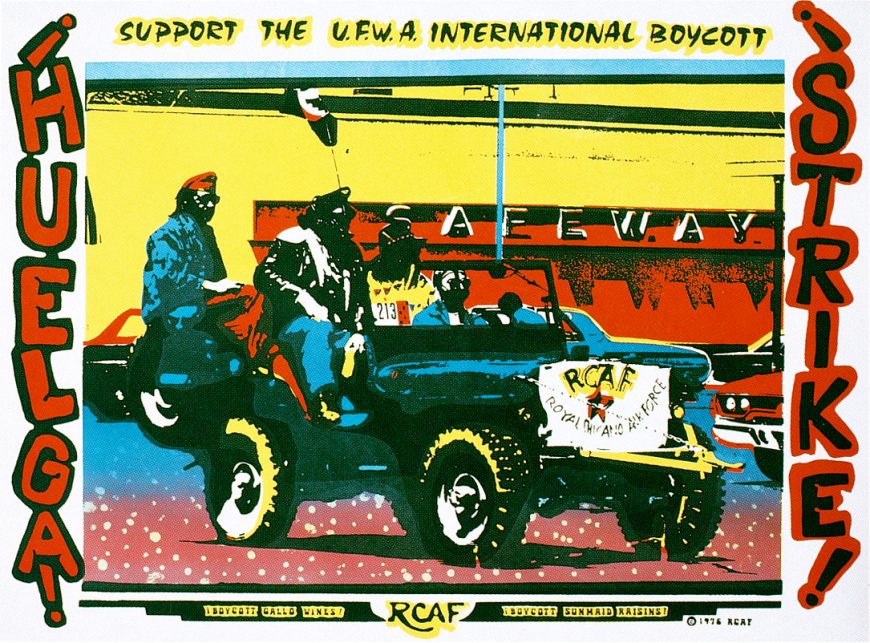

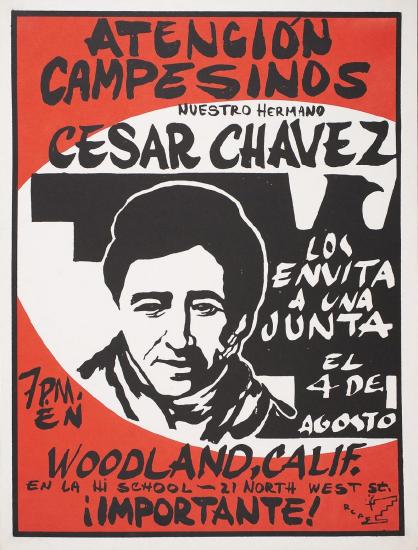

The Chicano Movement emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s against the backdrop of the broader civil rights struggles in the United States. Advocating for equality at work, at school, and in housing, immigration, and social justice, farmworkers, artists, activists, and students called themselves “Chicanos,” asserting proudly their Mexican ancestry as well as their place, history, and identity in U.S. society.

The Chicano Movement was multidimensional and artists played key roles in each realm. While Chicano artists like José Montoya worked with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to unionize the farm workers, artist Harry Gamboa led student walkouts in East Los Angeles. Gamboa and other Chicanx artists formed collectives like Asco (Spanish for “disgust”) while Montoya and others established the RCAF (Royal Chicano Air Force) to develop and disseminate their work through prints, murals, performances, and photography—media inherently accessible, participatory, and public.

Humor, politics, and public art

The RCAF was established in Sacramento, California in the early 1970s and was originally named Rebel Chicano Art Front (people confused the group’s acronym, RCAF, with that of the Royal Canadian Air Force, and so the more humorous Royal Chicano Air Force was adopted instead). The group was infused with humor from its inception, and the RCAF contributed to two major genres of Chicanx visual art—muralism and silkscreen printing. The RCAF is also credited with implementing art-based social programs that decenter the individual artist. In this way, Royal Chicano Air Force can be understood in relation to other art collectives of the 1960s and 70s—such as Fluxus—that also brought together musicians, writers, and artists in experimental performances that challenged the definition of art.

Chicanx identity & diversity

Inspired by the culturally nationalist doctrine of the Chicano Movement, described in El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan (1969) and El Plan de Santa Barbara (1969), both of which exalted the indigenous roots of Mexican-American identity, the RCAF visualized the movement’s platforms, aestheticizing a Mexican-American history and identity. In solidarity with the labor-rights campaigns of the United Farm Workers union (UFW), founded by Chavez and Huerta, the RCAF mobilized Mexican-American students, educators, veterans, artists, and activists calling for economic, educational, and political equality in the United States.

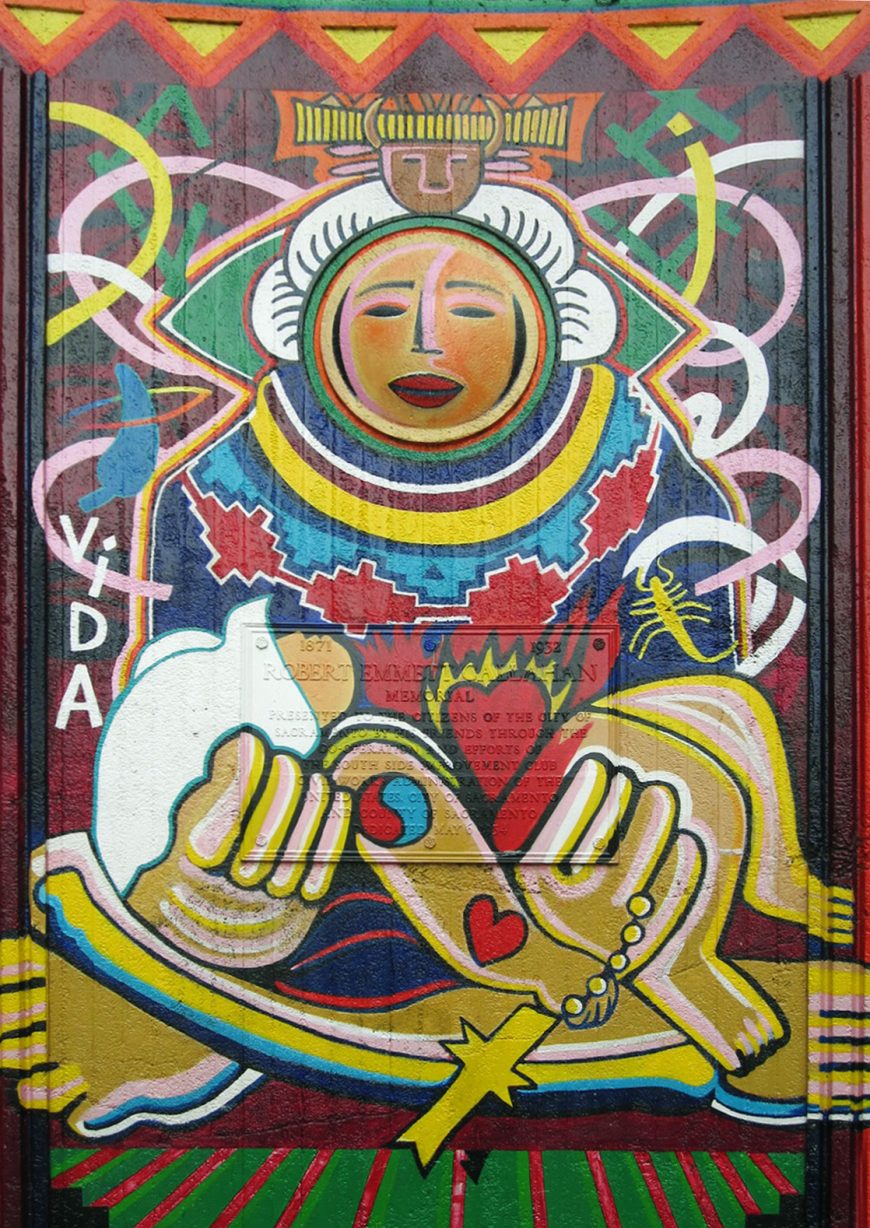

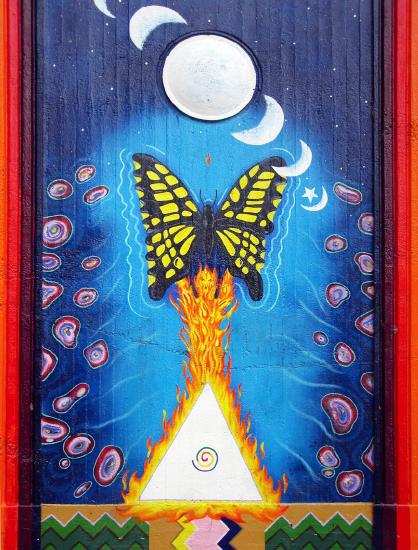

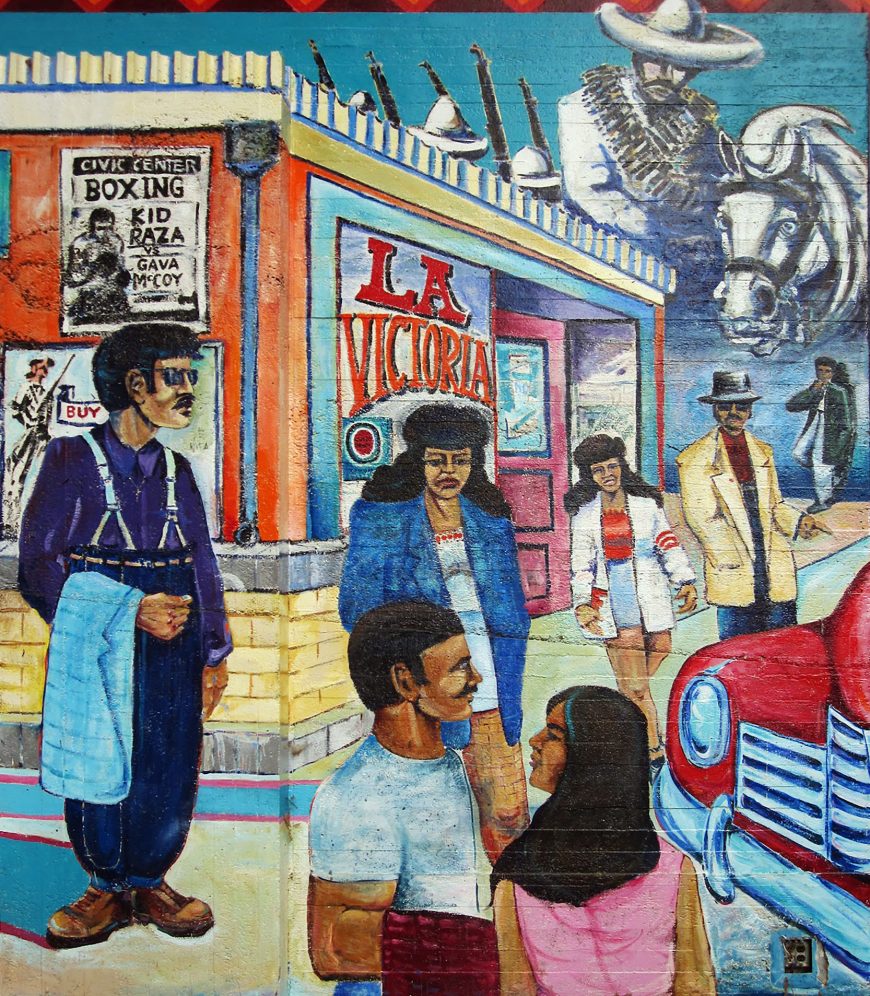

The group’s artistic diversity is evident in murals such as Southside Park Mural which consists of stylistically diverse panels by six artists extolling Chicanx culture and tradition. Created on an outdoor stage in Sacramento, the mural offers a culturally appropriate backdrop for community events, concerts, and festivals that celebrate Cinco de Mayo, Mexican Independence Day, and an athletic event called Barrio Olympics.

Mural as public forum

In 1976, RCAF artist Ricardo Favela and member Rosemary Rasul negotiated with city officials to create the park mural. José Montoya, Juanishi Orosco, Esteban Villa, Stan Padilla, Juan Cervantes, and Lorraine García-Nakata each painted the panels in their own styles, reflecting the collective’s diversity. The distinct styles and motifs of RCAF artists is perhaps best exemplified in the social realism of Montoya, which draws attention to the conditions of the working class, and the geometric abstraction of Orosco.

The mural panels draw on pre-Columbian, neo-Amerindian, and Chicanx youth iconography. For example, in the center panel, Esteban Villa painted a priest-like figure holding a newborn. The figures are rendered in broad strokes of color and a rosary, a Sacred Heart, and the word vida (life) can be seen. Flanking Villa’s panel on the left, Juanishi Orosco represented ojos de Dios (eyes of God) with Hopi influences, representing neo-Amerindian claims made during the 1960s and 70s Chicano Movement that sought to reconnect Amerindian cultures across the political border that now divides the United States from Mexico.

To the right of Villa’s panel, Padilla continued the neo-Amerindian theme by blending indigenous imagery with a visualization of the moon’s cycle and a monarch butterfly, a species native to the region but also a prototype for the RCAF’s Metamorphosis mural planned later that year and installed in downtown Sacramento by 1980.

José Montoya’s far left panel captures Pachuco/a couples: Mexican Americans of the 1930s and 1940s who participated in the “zoot suit” youth culture known as la pachucada. The scene gestures to the past represented by Mexican revolutionary heroes Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata who are identified by their mustaches, bandoliers, and sombreros. A young couple gazes up at the pachucos/as, suggesting a Chicanx future as they are a contemporary Cholo/a couple (a term for Mexican-Americans associated with a working-class culture rooted in la pachucada, but vilified in mainstream U.S. media as representing gang culture.)

The murals flanking the outer walls of the stage at Southside Park were created by Lorraine García-Nakata, one of the few Chicana artist members of the RCAF. García-Nakata designed, outlined, and painted two Amerindian women with open hands. While the women stand proudly with outstretched arms and from a position of power, they also seem to caution those who approach the stage, a message underscored by the size of their hands.

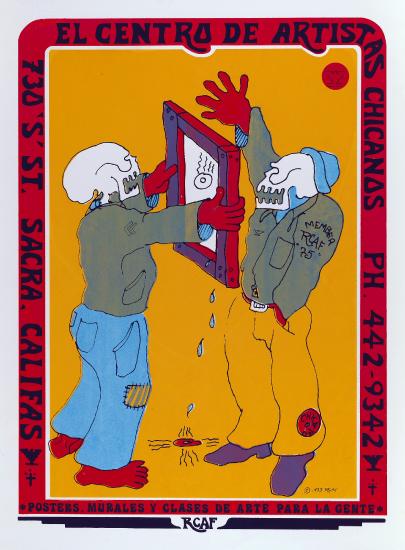

Centro de Artistas Chicanos

The RCAF championed aesthetic diversity and labor equality, exemplifying members’ commitment to the United Farm Workers’ labor platforms. The group also rejected the notion of individual artistic genius, and capitalist values of art ownership. In fact, the practice of signing work shifted to include both individual artist and the initials RCAF, a practice that dates to the late 1970s when institutions began to collect Chicanx artwork.

RCAF members were committed to public art. They painted murals and taught printmaking to their communities and to university students, as well as in local prison programs. They also exhibited artwork made by community members and by their students in both art institutions and in community spaces. In 1972, they founded the Centro de Artistas Chicanos as an operational hub for the RCAF and local area artists, in order to facilitate grants, teach classes, and better support community-based art programs.

Additional Resources:

Royal Chicano Air Force archives at the Online Archives of California

Royal Chicano Air Force in Calisphere, University of California Libraries

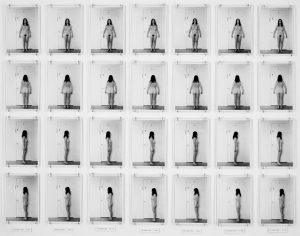

Eleanor Antin, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture

In 1972, the artist Eleanor Antin decided she would make an “academic” sculpture:

“I got out a book on Greek sculpture, which is the most academic of all….This piece was done in the method of the Greek sculptors…carving around and around the figure and whole layers would come off at a time until finally the aesthetic ideal had been reached.”

Of course she did no such thing—make an academic sculpture, that is. What she produced instead was a work entitled Carving: A Traditional Sculpture in which the typical marble or bronze medium of sculpture was replaced with a grid of 148 black and white photographs of the artist’s naked body. They are arranged in 37 vertical columns, corresponding to the number of days Antin spent following a diet plan proposed in a popular magazine for women. Each row consists of four photographs showing back, front, and side profiles, with a text panel at the bottom listing each day, time, and the artist’s weight. When first exhibited, the photographs were simply pinned to the wall, eschewing the conventional use of frames in the display of art.

It is not sculpture per se, but the performance of sculpture. We might think of it as sculpture transposed into a living form, which is then presented as documentation—an analytical practice somewhat akin to laboratory research. The result might seem more informational than artistic.

Critiquing representations of women

Carving: A Traditional Sculpture could be seen as one answer to the rhetorical question posed by art historian Linda Nochlin’s now famous essay published one year earlier: “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Nochlin’s argument was that the history of art included few women, not because there were few women artists of note, but because art history was an extension of a patriarchal system in which women were excluded from almost everything. The answer Nochlin proposed was not to simply re-insert women into history, but to scrutinize the very structure of history itself: to analyze the role of women within patriarchy, and by extension in the history of art.

Antin’s “traditional” sculpture is a witty and humorously feminist attack on tradition in which women were more often subjects than authors. Antin took the idea of sculpture as the subject of her work, thereby also following the dictates of Conceptual art, a dominant movement of the 1970s in which traditional notions of art were contested and redefined. Women artists at this time, in tandem with second wave feminism, embraced the Conceptual art movement’s focus on concepts and processes, its adaptation of new media, and its overturning of past artistic conventions.

Though the ancient Greeks predominantly sculpted male bodies, the lasting tradition of Western art, which was rooted in the classical ideal of ancient Greek and Roman art, was one in which the bodies of women served as primary subject matter. Subjected to scenarios of violence and abduction, and the distortion, abstraction and idealization that supposedly served the higher goals of art, that tradition became a key target of feminist interventions into visual culture in the 1970s.

Dispensing with clichéd notions of beauty and femininity, in this piece Antin presents her body for the purposes of critical analysis (signaled by the detached presentation in black and white) rather than visual pleasure, thereby presenting a critique of the ways women had been depicted in the history of art. However, it was not just the Western tradition of fine art that Antin interrogated in this conceptual sculpture. Popular culture similarly demands that women hold to an idealized form of femininity. Antin’s joining of these two mutually reinforcing systems—the weight loss program found in a typical “women’s” magazine and the chiseling away of stone to reveal an ideal form in academic art—became the template for women artists in the 1970s and 1980s who were interested in examining cultural representations of gender. (Mary Kelly and Cindy Sherman are two other important examples.)

Socially constructed, or essentially feminine?

Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture was one of the first artworks that looked critically at how women are portrayed within the contexts of both art and popular culture, but it represented only one strand of feminist art in the 1970s. Antin’s work could be viewed as an example of “social constructionism.” According to this way of thinking, imagery of women was seen as constructing, rather than simply reflecting, concepts of femininity.

A different school of thought, called “essentialism,” argued that a truly feminist art meant finding and highlighting an essential female aesthetic experience. Instead of analyzing women’s experience in relation to patriarchy, this approach argued that women’s art should be celebrated as separate in its own right. Judy Chicago’s massive installation The Dinner Party is an example of this theory. Created between 1974 and 1979, this work embodied a sense of essential femininity through a collaborative project that employed several hundred volunteers specialized in crafts (embroidery and ceramics, for example) that were typically associated with the domestic labor commonly practiced by women. The end result was a triangular dinner table with place settings dedicated to famous women in history and myth.

![]() Whatever the differences between these camps (and those differences would form a rich area of feminist scholarly debate in the years to come), by the 1970s the issue of gender could no longer be ignored. We can get a sense of how vastly different the new climate was when looking at a particular moment in a film, released the very next year, in 1973, after Antin first exhibited her work. Painters Painting: The New York Art Scene 1940-1970 was a documentary of the school of painting that had reigned since World War II. At one point in the film, the artist Helen Frankenthaler, known for her stained abstractions in which pools of color saturated the canvas, was asked “What was it like to be a woman painter?” Like many female modernists, Frankenthaler had faced the hostility of critics who claimed women did not have the wherewithal to produce the heroically large abstractions of their male counterparts. But Frankenthaler was clearly uncomfortable with the question. Despite the fact that she had just given an impressive overview of the history of modernist painting and the problems it represented for her own generation of artists, Frankenthaler’s only response to this question was a brief one—“well first of all I am a painter”—followed by an averting of her eyes. For the younger generation that came of age in the 1960s, this was no longer a tenable position. The personal was political, as the saying would go, but so too was the aesthetic.

Whatever the differences between these camps (and those differences would form a rich area of feminist scholarly debate in the years to come), by the 1970s the issue of gender could no longer be ignored. We can get a sense of how vastly different the new climate was when looking at a particular moment in a film, released the very next year, in 1973, after Antin first exhibited her work. Painters Painting: The New York Art Scene 1940-1970 was a documentary of the school of painting that had reigned since World War II. At one point in the film, the artist Helen Frankenthaler, known for her stained abstractions in which pools of color saturated the canvas, was asked “What was it like to be a woman painter?” Like many female modernists, Frankenthaler had faced the hostility of critics who claimed women did not have the wherewithal to produce the heroically large abstractions of their male counterparts. But Frankenthaler was clearly uncomfortable with the question. Despite the fact that she had just given an impressive overview of the history of modernist painting and the problems it represented for her own generation of artists, Frankenthaler’s only response to this question was a brief one—“well first of all I am a painter”—followed by an averting of her eyes. For the younger generation that came of age in the 1960s, this was no longer a tenable position. The personal was political, as the saying would go, but so too was the aesthetic.

Additional resources:

This work at the Art Institute of Chicago

The Dinner Party at the Brooklyn Museum

Eleanor Antin cited in Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, eds, Framing Feminism: Art and the Women’s Movement 1970-1985 (Pandora Press, 1987), p.271.

Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (1971) in Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (Thames & Hudson,1989).

Painters Painting: The New York Art Scene 1940-1970, 1973, documentary directed by Emile de Antonio.

Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document

by RACHEL WARRINER

Anyone who has been in the unpleasant position of changing a dirty nappy will know that normally your first instinct is to get it as far away from it as possible. So it might seem strange that American artist Mary Kelly (born 1941) took the liners of her son’s used cloth nappies, printed them with details of his diet, and displayed them as artworks. Causing some controversy at their debut exhibition, the nappy liners formed the first part of the epic and fascinating Post-Partum Document (1973-79).

Kelly has made works that examine complicated social issues such as the ramifications of war, and the politics of how our identities are constructed. In Post-Partum Document, she was engaging in a discussion that was happening at the emergence of second-wave feminism about the way in which women worked in the home. At a time where many feminist artists were looking at reclaiming the body through performance – such as Marina Abramovic and Carole Schneeman – or revising history in order to incorporate our foremothers – such as Judy Chicago – Kelly looked more directly at the invisible daily experience of women engaged in domestic labour.

Post-Partum Document consists of six sections of documentation that follow the development of Kelly’s son, Kelly Barrie, from birth until the age of five. Kelly intricately charts her relationship with her son, and her changing role as a mother by writing on artefacts associated with child care: baby clothes, his drawings, items he collects, and his first efforts at writing. In addition, there are detailed analytical texts that exist in parallel to the objects.

In ‘Documentation III: Analysed Markings and Diary Perspective Schema,’ Kelly includes three types of text. She describes them in the documentation that accompanies their exhibition as:

R1 A condensed transcription of the child’s conversation, playing it back immediately following the recording session

R2 A transcription of the mother’s inner speech in relation to R1, recalling it during a playback later the same day

R3 A secondary revision of R2, one week later, locating the conversation (as object) within a specific time interval (as spatial metaphor) and rendering it “in perspective” (as a mnemic system)

Kelly’s documentations that accompany the work are heavily indebted to Lacanian psychoanalysis, which conceives of the unconscious as being structured like a language. This is interesting in relation to Post-Partum Document because it is so layered with text. The quote above strongly contrasts with extracts taken from column R1 (the transcripts) from the piece dated 27.9.75, which is written in lowercase on a typewriter. They state:

Come’n do it (wants to fly the kite)

Down dis, its falling. (I’m pretending to fly the kite)] Ask Daddy flying the kite, go ask him (I say Daddy will fly it tomorrow)

We can see how much range there is in the text that she uses. Adding to this, there are the sections in R2 that provide a picture of an adult’s day to day interaction with a small child. This column is typed in capital letters, using the aesthetic of the text in order to separate the voices. From the same piece R2 reads:

I say it would be nice to take it outside as it’s very windy but it’s also very late so I try to change the subject.

As I started this game of pretending to fly the kite standing on a chair holding it and making sounds like wind, now I’m stuck with it.

He remembers promises very well.

Finally, in section R3, Kelly describes her anxiety following an accident in which her son drank liquid aspirin and had to be rushed to hospital. This section is handwritten and is much longer, with candid text that explores the difficulties of childrearing. A part of this section states:

Sometimes I forget to give him his medicine which makes me feel totally irresponsible or I just feel I wish it was all over i.e. he was ‘grown up’ but my mother says it never ends the worry just goes on and on.

Over the top of all this worry and analysis are Kelly Barrie’s drawings. They are typical of the drawings made by a young child, not much more than scribbles on rice paper. However, his lines cut over his mother’s careful work; their carelessness seems all the more free when contrasted with her deliberations.

What makes this piece important is the way in which motherhood—so often seen in art history as a sentimental connection between mother and child—is shown as a difficult and complex relationship. Kelly’s voice does not overbear her son’s, instead it exists in tandem; we see Kelly develoraping and adapting as much as her child.

This is an extensive project (comprising in total of 139 individual parts) and Kelly’s attention to the material qualities of these mundane objects is outstanding. This piece is a central work within feminist art that is still a relevant and a fascinating picture of what motherhood means for women.

Additional Resources:

Mary Kelly Artist Website

Mary Kelly at Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (1976)

Jackie Winsor, #1 Rope

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Jackie Winsor, #1 Rope, 1976, wood and hemp, 40-1/4 x 40 x 40″ (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: