10.2: Key concepts

- Page ID

- 64985

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Modern art and reality

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

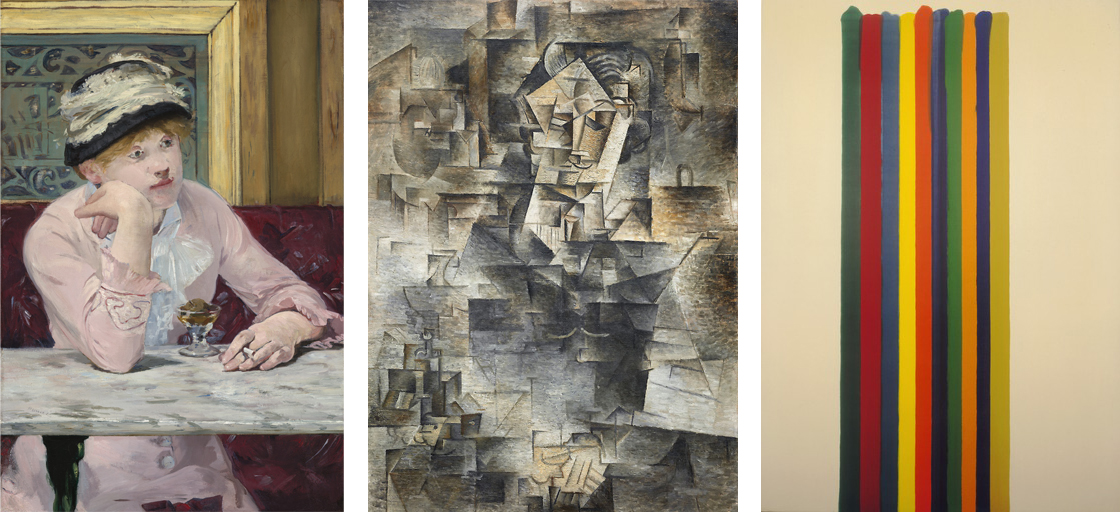

If asked, most people would probably say that modern art is not true to reality. Indeed, modern art is practically defined by its bizarre distortions of reality; this is one reason why Norman Rockwell, whose work is more recent than Umberto Boccioni’s, is not considered a modern artist. But looking like reality — what art historians call “naturalism” — is only one way of being true to reality. As we shall see, the attempt to create art that was more true to reality than traditional naturalism was the motivation for some of the most radical modern art, even including Boccioni’s States of Mind: The Farewells.

Impressionism and optical realism

When the Impressionist style first appeared on the art scene of the 1870s, many hostile viewers dismissed it as art by “lunatics” whose color perception was questionable and who did not have the technical skills to properly finish their paintings. Some critics claimed, however, that Impressionist paintings were more accurate than traditional naturalistic representations. Their argument was that the Impressionists represented their perception of objects rather than the objects themselves, and that the colors we perceive are often not identical to an object’s actual or “local” color.

In the 1890s, Monet created dozens of paintings of Rouen Cathedral at different times of day and in different weather. At dawn, the cathedral was tinged with blue light; in the late-afternoon, it was radiant with oranges and yellows; while on cloudy days it was a duller grayish tan. By recording how the appearances of objects are affected by different lighting conditions, the Impressionists argued that their paintings were more accurate representations of the way we see the world. What appears at first sight to be a radically unrealistic style is in fact more true to the way things actually look.

Discarding artificial conventions

The Impressionists recognized that much traditional art was accepted as true to reality only because it was familiar, not because it was accurate. For example, methods of composition taught in Academies tended to emphasize a central focus, equal balance on both sides, and a clear depiction of spatial recession, as in David’s Oath of the Horatii. Such compositions are, in fact, very artificially staged. When we move through the world, we are more likely to encounter scenes like the one represented in Degas’s The Race Track: awkwardly unbalanced, abruptly cropped, and spatially ambiguous. Critics who supported the Impressionists argued that artists like Degas were correcting artificial conventions and making art more true to reality.

Although the Impressionist style was new, this form of argument was not. In the sixteenth century artists and critics tried to draw a distinction between a true naturalism and a false naturalism (often derogatorily called “Mannerism“). False naturalism involved copying the work of other artists, and thus understanding nature only at second hand. The solution, some felt, was to discard the conventions of art and return to a more careful study of the original source, nature itself, just as the Impressionists did.

Is naturalism true to nature?

Impressionist artists sought greater truth to nature through more careful observation, but there is a sense in which our eyes inevitably distort the objects they perceive. Three ways they do so are embodied in the artistic techniques of linear perspective, diminution, and foreshortening.

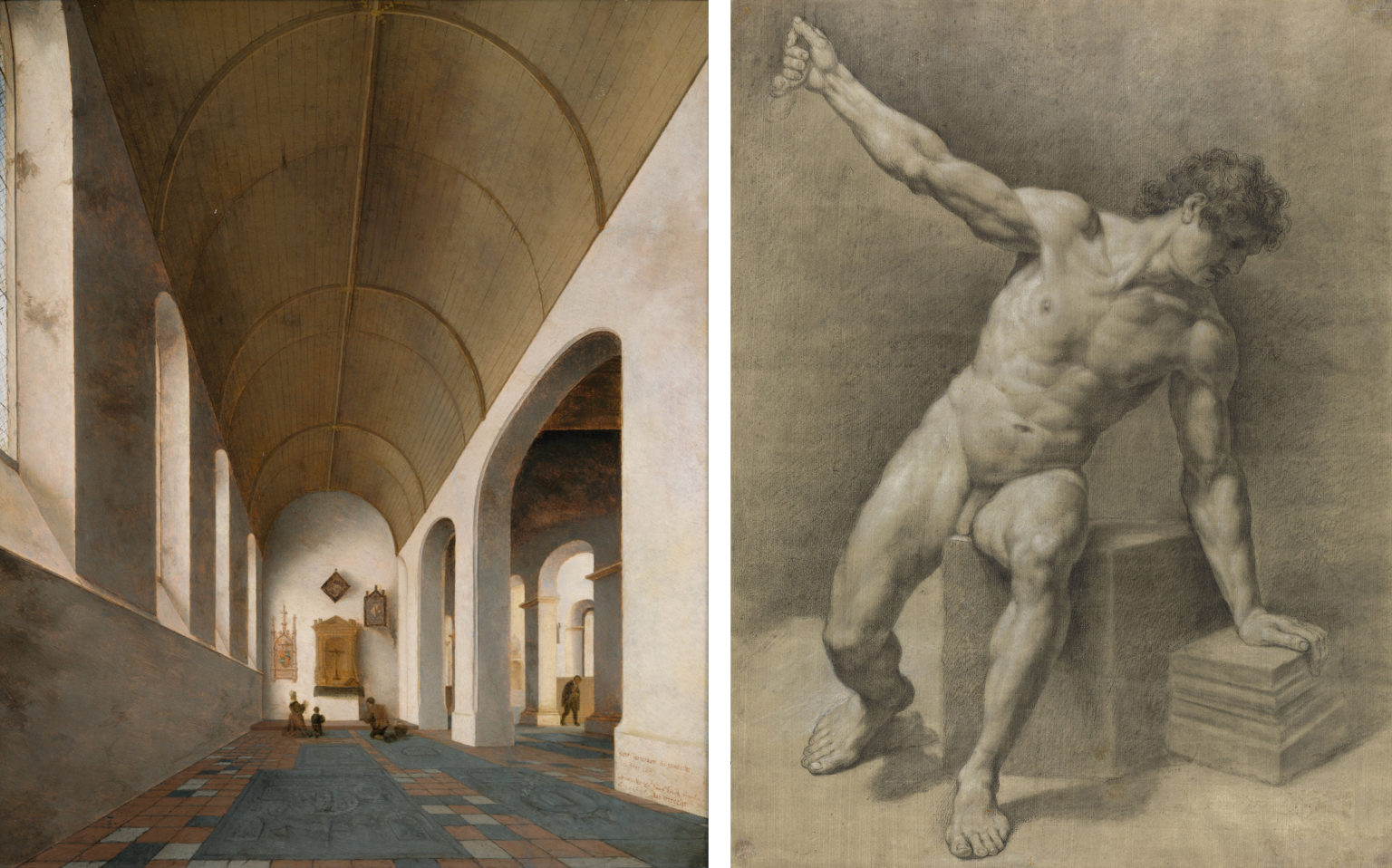

In linear perspective, what are actually parallel lines in real life (such as railroad tracks or the edges of floor tiles) converge in the representation. This effect, seen above in the Saenredam painting of a church interior, is integral to what is popularly considered a realistic style, but it is obviously not true to reality. Each of the tiles on the floor is in fact square. Similarly, with diminution, objects appear to get smaller the farther away they are, but this is just an optical trick; each of those windows is in reality the same size.

Foreshortening occurs when we view an object from an angle at which it recedes away from us, so that the object appears to be contracted, shorter than its actual length. In the Academic figure study above on the right, the two thighs appear to be of different lengths and shapes simply because one is viewed parallel to the picture plane while the other is receding sharply away from it. In actual reality, of course, both thighs are very similar (mirror images) in length and shape.

Correcting for perceptual distortion

The style we colloquially call “realistic” is not literally true to reality, then. It is only a record of our perception of reality, from one angle, at one distance, at one moment in time, and in one kind of light, and all of these factors can distort the object. Some Modern art movements sought a representational system that would be more accurate to the true shapes of objects, rather than representing them deformed by perception.

Cubist paintings seem at first sight to be even more bizarrely distorted and unrealistic than Impressionist paintings. In the Salon Cubist Jean Metzinger’s Le Goûter, objects appear to be twisted and broken up, but this is done in order to correct the distortions of perspective and foreshortening. Metzinger shows things from multiple perspectives so we can better understand their true shapes. The left side of the tea cup on the table is seen from the side at eye level, but from that angle you wouldn’t be able to tell that the cup has a round opening, so the right side is seen from above to complete our understanding of the round lip and concave shape of the cup. Similarly, one of the woman’s eyes is viewed in profile, while the other is seen facing us, and her left shoulder is seen from above, while the right is more straight on. Cubism doesn’t “distort” objects; it shows them from multiple angles in order to give us more information about their true shapes than would be visible in traditional naturalistic representation.

Modernism and science

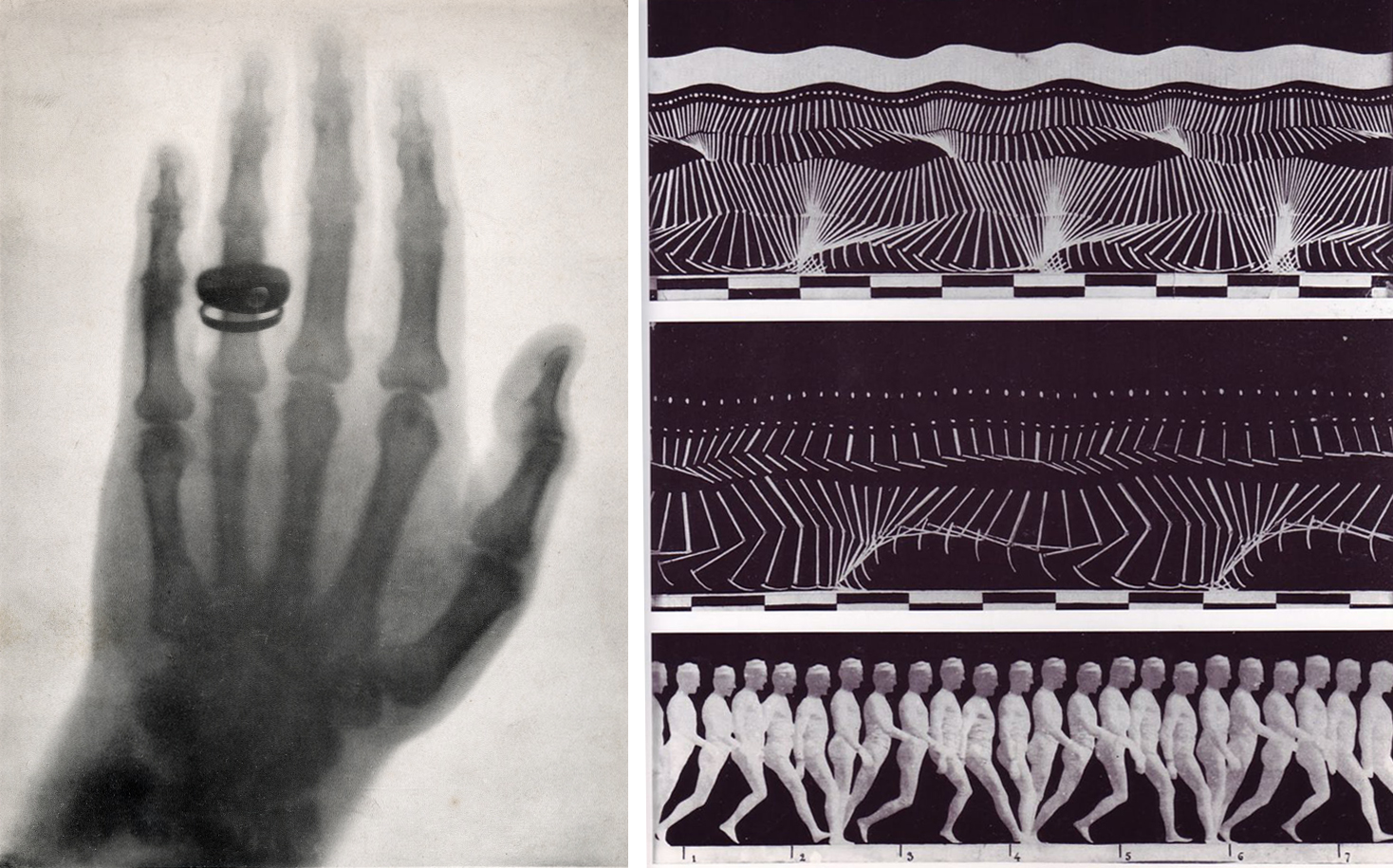

Another way of justifying the apparent distortions of modern art came in the form of appeals to science. Modern science provided a stream of new images that sparked artists’ imaginations, as well as new theories that radically altered people’s understanding of reality.

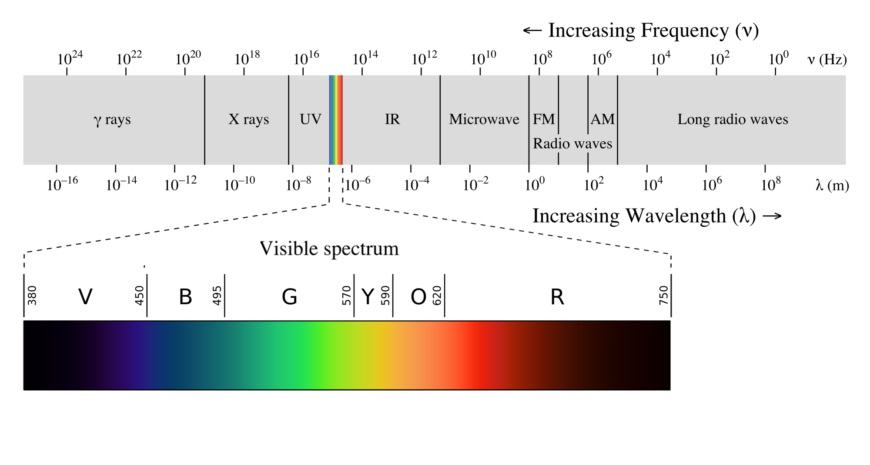

Beginning in the seventeenth century, new technologies based on the use of optical lenses provided evidence of microscopic and macroscopic worlds hitherto unsuspected. The discovery of wavelengths beyond the visible spectrum, including infrared and ultraviolet light as well as x-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves, made it clear that the human senses are very limited instruments for understanding the objective world. The visual culture of modern science provided new ways of representing and understanding reality. Stop-motion photography made rapid actions visible for study, and x-ray photography allowed peeks into the interior of solid forms, resulting in visions of reality beyond traditional naturalism.

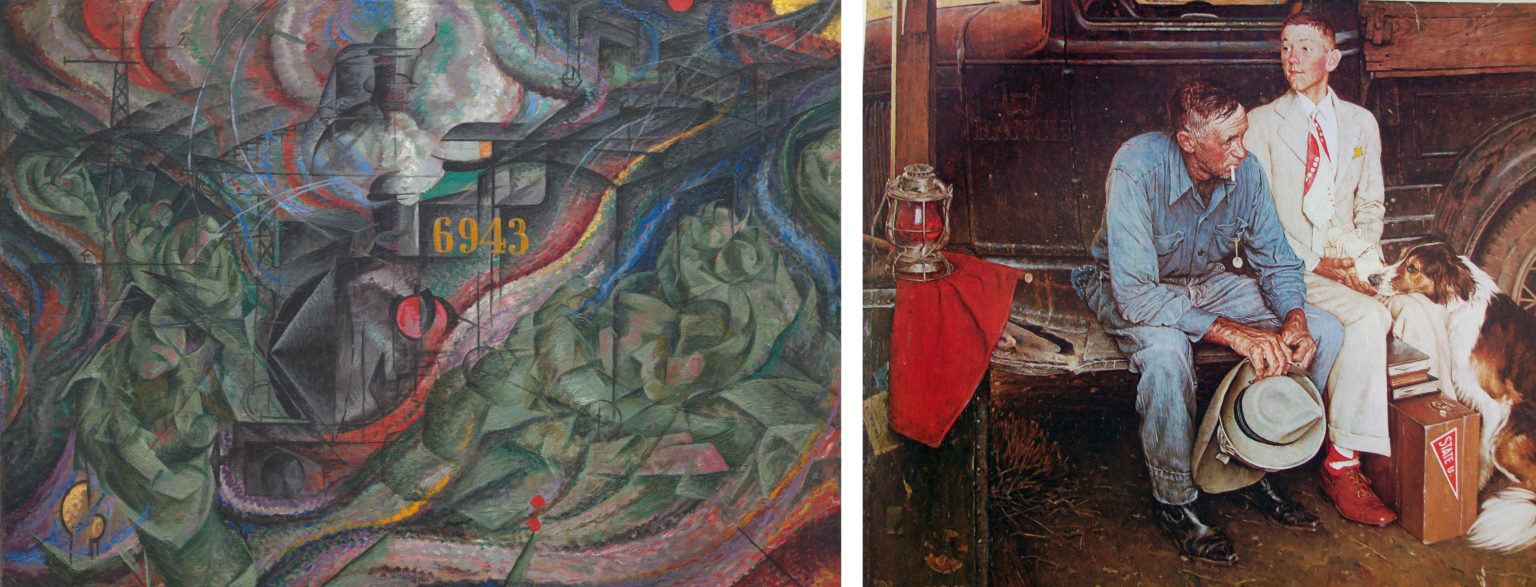

One work that attempted to represent this new super-sensory reality was Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni’s States of Mind: The Farewells (1911). The only clearly legible feature in the painting is the number 6943 stenciled on what we gradually discern is the engine of a dark-gray train engine spewing steam in a station. The train is represented, Cubist-fashion, from multiple perspectives. The nose cone is in profile, while the body of the train recedes in a zig-zag toward the upper right then upper center of the canvas. In front of the train in green are a series of a couples saying goodbye (their two heads and embracing arms are clearest in the lower left) — or perhaps they are one couple, viewed multiple times in the manner of stop-action photography in order to show motion through time.

Two truss structures on the left suggest the radio towers that were constructed across Europe in the first decades of the twentieth century after the Italian Guglielmo Marconi harnessed radio waves for wireless communication. Correspondingly, the remainder of the composition is permeated with wave-forms in bright colors to suggest their high energy. Many forms of electromagnetic energy such as radio waves are invisible to the eye, but nonetheless permeate the world. Altogether, the work makes visible the new understanding of nature achieved by modern physics and presents a glimpse of reality beyond the limitations of the human senses.

Modernism and spiritualism

Modern artists’ quest for truth to realities beyond human perception was also influenced by the explicitly non-scientific approaches of spiritualism. Although spiritual visions and discoveries are often seen as subjective, many modern artists saw them as revealing objective truths. They claimed their depictions of these discoveries were glimpses of a higher reality than that available to the human senses.

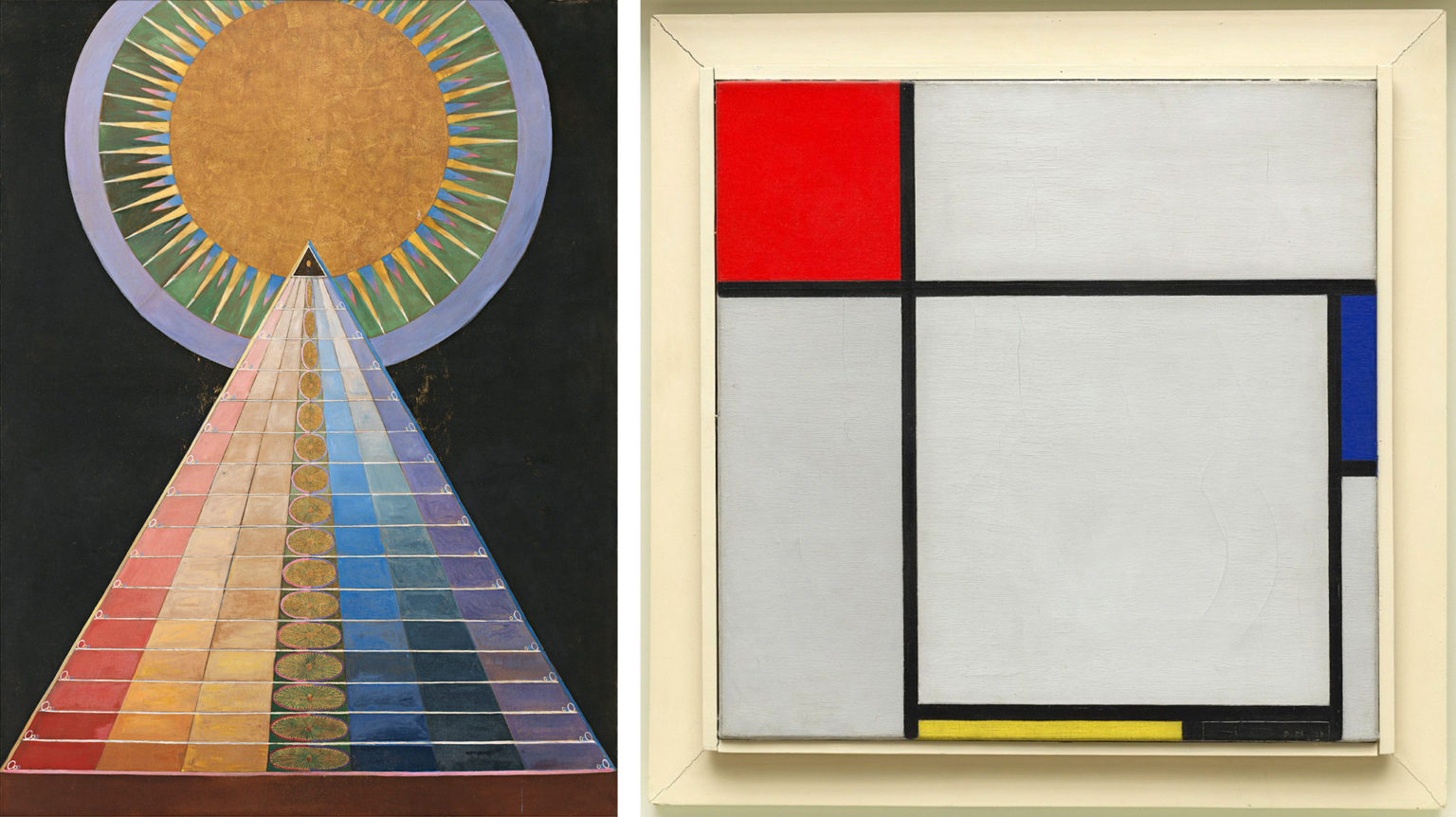

The Swedish artist Hilma af Klint painted a series of works called The Paintings for the Temple between 1905 and 1915 based in part on mystical visions she received from a spiritual guide. Around the same time, the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian undertook a close study of nature to eventually discover what he felt were the basic “building blocks” of all natural and artistic form: the primary colors red, yellow, and blue; the primary values black and white, and horizontal and vertical lines. Although both of these artists produced some artworks that are entirely non-representational in the sense that they do not look like nature, both argued that their spiritual quest revealed a higher reality than that available to the senses.

These artists all remind us that what is popularly considered ”realistic” in art is in fact only based on sense perceptions, which are inevitably partial, and which in many cases distort reality. By observing nature more closely, discarding artificial conventions, correcting for perceptual distortions, absorbing new scientific theories, and engaging in spiritual investigations, many modern artists rejected traditional naturalism in order to seek higher truths.

Expression and modern art

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

In his painting The Old Guitarist, Picasso made a series of choices to evoke feelings of pity. The guitarist is an old man, with gray hair. The fact that he is seated on the ground suggests that he is playing on the street for spare change. His emaciated state, torn clothes, and dejected posture show poverty and depression.

Furthermore, Picasso does not simply paint the old guitarist exactly as he would appear in real life; he deliberately distorts or exaggerates certain aspects of the scene in order to further intensify his intended expression. Most obviously, the entire work—except for the guitar—is in blue monochrome. This is clearly unrealistic, but it capitalizes on the melancholy emotional quality associated with that color.

When we compare Picasso’s painting to one of a very similar subject by Edouard Manet, we can see other strategic formal distortions. Picasso’s guitarist is in an improbable (if not impossible) pose that is cramped on all sides by the frame. He looks caged or trapped, where Manet’s guitarist, already in a more dynamic pose with his energy thrusting upward, has room to move within the frame. Also, where the form of Manet’s guitarist flows through organic, rounded curves, Picasso has exaggerated the hard angularity of his guitarist, who appears to be all jutting elbows, ankles, and tendons.

These two works exemplify the difference between naturalism and expression as artistic goals. One of Manet’s primary goals was an accurate depiction of the appearance of the guitarist, what art historians call naturalism. As to how to feel about him, we are left largely on our own: it is equally probable that a viewer could pity his evident poverty (examine his worn shoes, five o’clock shadow, and simple meal), or admire his bohemian freedom. Picasso, by contrast, paints his guitarist in an expressive manner, explicitly directing our feelings through his stylistic choices.

Picasso’s willingness to sacrifice naturalism in order to enhance the emotional impact of The Old Guitarist is what makes the painting exemplary of modern expression. Between the Renaissance and the nineteenth century (with some notable exceptions, such as El Greco), artists would primarily evoke emotions in ways consistent with naturalism.

In his Deposition, the Baroque artist Caravaggio uses spotlighting, gritty earth colors, and body language to help express the emotional drama of the moment Christ’s body is laid in the tomb, but nothing is too distorted. The work remains naturalistic; you could see such a scene in real life. Romantic artist J. M. W. Turner pushes the boundaries more in his Slave Ship, with obviously painterly brushwork and very intense color, but the painting still looks plausibly like a storm at sea, with the whipping spray and blowing clouds backlit by the setting sun. The Baroque and Romantic periods both emphasized expression as an artistic goal, but both also largely stayed within the confines of naturalistic representation.

Starting in the later nineteenth century, the expressionist art movements of the Modern period were increasingly willing to sacrifice naturalism in pursuit of more powerful expressive effects. Although Edvard Munch’s The Scream does include expressive body language in the foreground figure, the painting’s emotional charge is largely carried by its formal distortions. We react first of all to the expressive power of the work’s acrid color, vertiginous recession, and nauseatingly undulating composition, which have been exaggerated to the point where the depicted scene is no longer plausible. Expression has superseded naturalism as the main aesthetic goal. The Modern period saw an increasing recognition of the expressive power of form — color, line, shape, composition, and so on. It is no great conceptual leap from Munch to Joan Mitchell, for whom pure form conveys pure expression, as the name of the Abstract Expressionist movement suggests.

Ex-pression as non-rational

The prefix “ex” means “out,” so to ex-press literally means to push out, reconfirming the distinction between expression and representation or naturalism. In the latter, the motive for the work is out in the world, part of nature, and the artist just re-presents it. With ex-pression, the motive for the work is inside the artist, a mental or emotional state, and must be pushed out.

Expression in art history is generally associated with non-rational states of mind. It is not used to describe works that convey objective facts or for ideas arrived at through rational thought processes. In addition to emotions, the term expression is also used for works that convey spiritual content, such as Vasily Kandinsky’s apocalyptic paintings of the 1910s, and subconscious content, such as the Surrealist André Masson’s automatic drawings of the 1920s.

Because it pertains to non-rational states of mind, expression is often associated with spontaneous or even involuntary creative processes, both mental and manual. While naturalistic art is generally acknowledged to require intensive training, the skills associated with expressionist art are often said to be innate. Correspondingly, rapid or unrefined execution is frequently taken as a sign of expressive intensity, as though the artist’s hand were responding in automatic synchronization with the outpourings of the emotions or unconscious. This is not a universal stylistic characteristic of modern expressionist art, but it is common, as the examples above of Turner, Munch, Mitchell, Masson, and Kandinsky all demonstrate.

The stereotype of the expressionist artist

There is a stereotype of the expressionist artist that — not coincidentally — matches the qualities associated with expressionist art: almost pathologically irrational, careless of social conventions, and spontaneous to the point of being out of control. It seems that in order to express intensely, the artist has to live intensely. Many analyses of The Old Guitarist begin with the story of Picasso’s own adversities at the time, when he was living in poverty in Paris and had just lost a close friend to suicide. Similar stories of the Post-Impressionist Vincent van Gogh’s madness, the German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s wartime trauma, and the American Neo-Expressionist Jean-Michel Basquiat’s life on the streets are often used to validate the expressive authenticity of their art.

We need to maintain a distinction between expression and self-expression, however. The term self-expression is reserved for works whose primary intent is to communicate something about the artist him- or herself. Most modern expressionist art had a broader goal than this. Even when modern artists drew from their own experiences, the intent was to create works that express something about the society or culture of their time, or about the wider human condition. Truly self-expressive works are of limited relevance to outside viewers; this is why art historians typically try to relate works to issues beyond the personal biography of the artists who created them.

Not all modern art is about expression

The concept of expression and the stereotype of the expressionist artist are probably the most commonly evoked justifications for modern art in the popular understanding. If the work does not look like reality, many people assume that it is because the artist was trying to express something, rather than depict something. However, expression of non-rational mental states is only one potential goal of art, and although it was a particularly prominent goal during the modern period, it is not the only motive for non-naturalistic art. We explore other broad answers to the question, ‘Why doesn’t modern art look like reality?’ in the essays The ambiguity of “realism”, Formalism I, and Formalism II.

Primitivism and Modern Art

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Primitivism in art involves the appreciation and imitation of cultural products and practices perceived to be “primitive,” or at an earlier stage of a supposed common scale of human development. This definition contains a basic contradiction: the primitive is admired and even seen as a model, but at the same it is also presumed to be inferior, because it is not fully developed. This paradox makes primitivism a concept that is both intellectually and morally complex.

Primitivism in a broad historical context

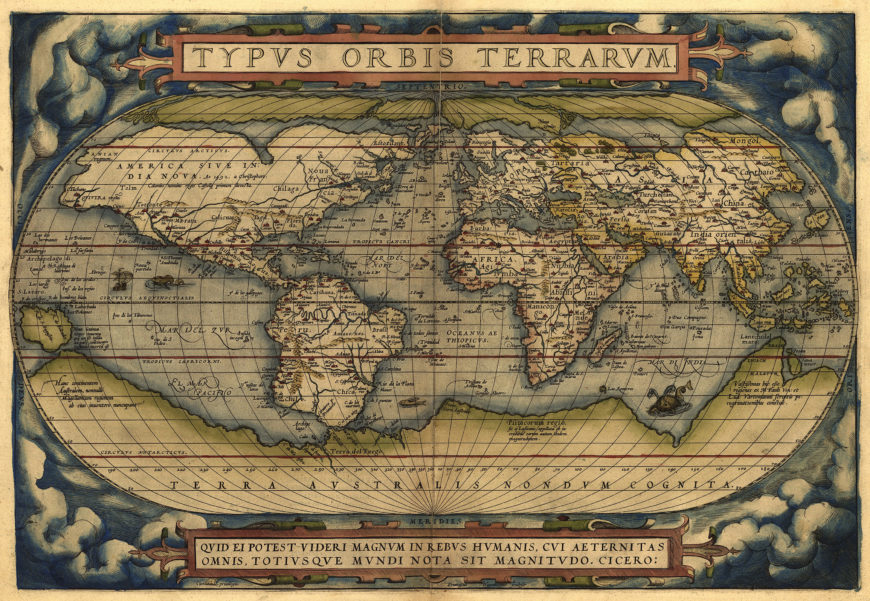

Primitivism was fostered during the modern period by two phenomena. First, the so-called Age of Discovery from the 15th through the 17th century brought Europeans into close contact with a wide array of previously unknown cultures from Asia, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. As a result of the military and technological advantages of the West, the new social and economic relationships established with these cultures were often exploitative, including theft of raw materials, enslavement, and colonial rule.

The body language in Luigi Persico’s Discovery of America exemplifies such relationships. The male European “discoverer” stands dominant, dressed in Renaissance-style metal armor and carrying a sphere that simultaneously represents the globe he has conquered and the “enlightenment” he brings, while the nearly-naked indigenous woman cringes, awestruck and submissive, by his side.

Second, primitivist attitudes were fostered by anxieties caused by the rapid social, economic, and political changes that accompanied the scientific and industrial revolutions of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

Within a few hundred years, cultural patterns based on religion and agriculture that had lasted for millennia were upended. Science was displacing faith, and machines were replacing human labor or creating lower-paying, unskilled jobs. Increasing numbers of people lived in cities rather than in villages and worked in factories rather than on farms. Primitivism was a sort of antidote to modernity itself, a nostalgia for an imagined “state of nature” when humankind is assumed to have lived more instinctually and in closer harmony with the natural and spiritual worlds.

The “noble savage”

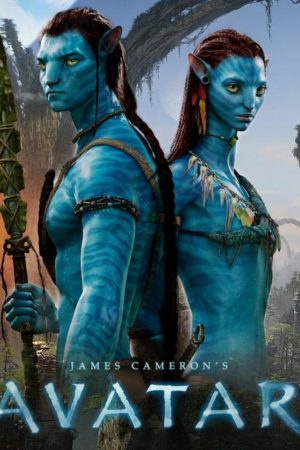

One of the defining concepts of primitivism is that of the “noble savage,” an oxymoronic phrase often attributed to the eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, although he never used it. Now recognized as a stereotype, the noble savage is a stock character of literature and the arts who may lack education, technology, and cultural refinement, but who lives according to universal natural law and so is inherently moral and good. Many popular books and films exemplify the concept of the noble savage, including Tarzan, The Gods Must Be Crazy, Dances With Wolves, and Avatar.

In Avatar, for example, the indigenous, blue-skinned Na’vi are technologically inferior to the humans who come to mine their Eden-like world for resources, but they are morally superior and closer to nature. Although the Na’vi are loosely based on Native Americans, it is important to remember that the primitivist concept of the noble savage is essentially mythic, not documentary.

Tropical paradise

The late-nineteenth century French artist Paul Gauguin created some of the most enduring and influential images of the noble savage. Decrying the corruption of “putrified” Europe, Gauguin left France in 1891 for the South Pacific island of Tahiti, where,

under an eternally summer sky, on a marvelously fertile soil…the…happy inhabitants of the unknown paradise of Oceania know only the sweetness of life.

Paul Gauguin, letter to J. F. Willumsen, Pont-Aven, 1890, as translated in Herschel B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art (London, 1968), p. 79.

Although aspects of Gauguin’s paintings of Tahitian life have some basis in reality, they combine multiple cultural traditions, including South Asian and Egyptian as well as Oceanic. They are also carefully selected to reinforce pre-existing European stereotypes of a tropical paradise replete with colorful plants, succulent fruits, and quaint superstitions.

Gauguin’s paradise is populated largely with young, semi-nude women, promoting fantasies of sexual freedom as well as perpetuating a long-standing European convention that associated women with nature. The model for The Seed of the Areoi was a thirteen-year-old Tahitian girl who was soon to be pregnant with Gauguin’s child. For many people today, Gauguin’s exploitative relationship with the Tahitians outweighs the admiration he professed to be expressing, and perhaps even his artistic legacy.

Gaucherie and sincerity

Gauguin’s primitivism extends to his style as well as his subject matter. He did not wish to represent “the primitive” second-hand, he aspired to live it and embody it. Notice the stiffness of the girl’s pose, the reduction of her anatomy to basic geometric shapes, and the near-total absence of chiaroscuro or cast shadows.

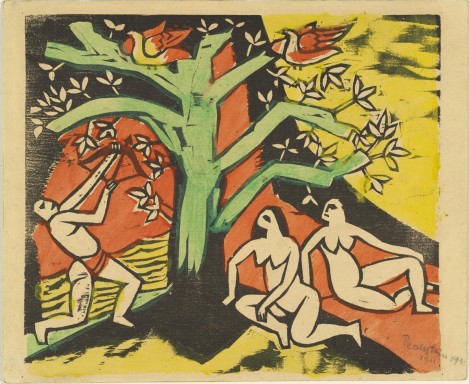

Along with an appreciation for “primitive’” subject matter, many modern artists also cultivated a style that they saw as primitive. Prototypes of this style were found in children’s art, folk art, and pre-Renaissance art as well as non-Western art. Gaucherie — awkwardness — was seen as a mark of sincerity and striving, which was preferable to the shallow facility of Academic art.

In addition, the naturalistic style taught in the Academic system was seen as being suited only to representing the surface appearances of material objects. Artists in search of alternatives to naturalism saw in primitive art and folk art a truly natural way to draw: one available without training, and one that is responsive to the richness of human subjective life: concepts, emotions, and spirituality, rather than a mere record of perceptions.

Similar stylistic qualities are seen in French customs-inspector-turned-artist Henri Rousseau’s The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope. Rousseau lived most of his life in Paris, and his experience with primeval tropical environments was limited to trips to the zoo and botanical garden. However, his self-taught, naïve painting style meant he was widely admired as a modern primitive.

Cultural appropriation?

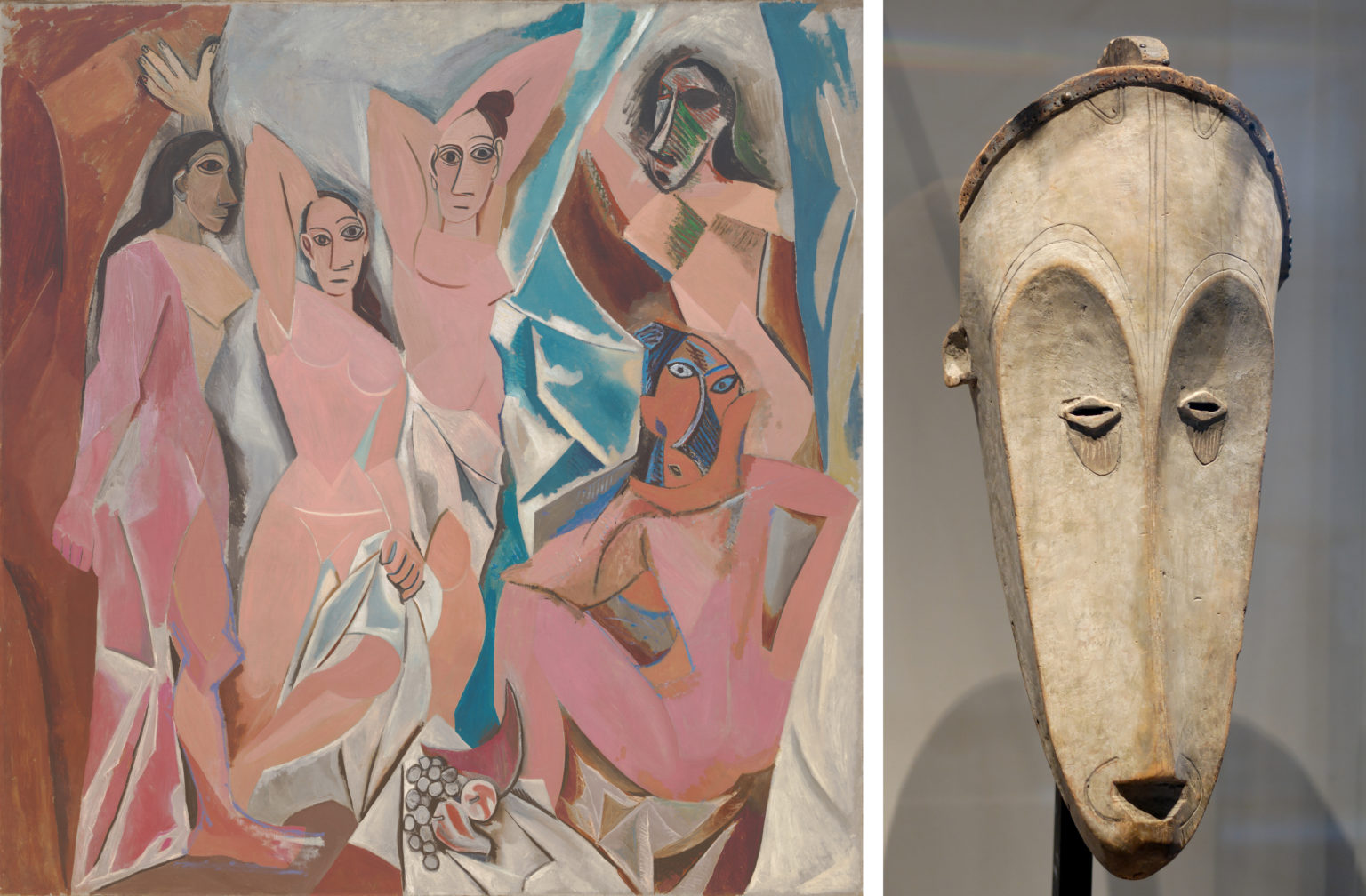

In 1907, a famous cross-cultural artistic encounter took place when Picasso went to see the African masks exhibited at Paris’s Trocadero Museum of Ethnology. Shortly thereafter, he revised the ambitious painting of prostitutes that he was working on to include mask-like faces on the two rightmost figures. Thus began a two-year engagement with African art that contributed to the invention of Cubism.

In the end, Cubism became very different from African art, but Picasso’s borrowings have raised concerns about cultural appropriation that are endemic to much primitivism. It is almost impossible to avoid consuming or using elements of other peoples’ cultures — blue jeans, paper, and pizza were all invented by and specific to one particular culture at one time. The charge of “cultural appropriation” is generally only leveled when a member of a dominant culture gains money or cultural capital by appropriating artifacts of a non-dominant culture. The vast commercial success of white, blues-based rock-and-roll musicians when their black progenitors lived in relative poverty is a good example.

It is hard to determine exactly how much of Picasso’s success is due to his cross-cultural borrowings, but certainly his enormous reputation and the astronomical prices commanded by his works at auction form a poignant contrast to the often literal anonymity of the mask-makers from Africa whose works helped inspire his artistic innovations.

Primitivism and industrialization

The German Expressionists were another group of artists who found inspiration in African art. Like Gauguin, they were motivated by an antipathy toward industrialization and the social and economic changes that it entailed, especially what they saw as a vain, shallow, and exploitative middle class.

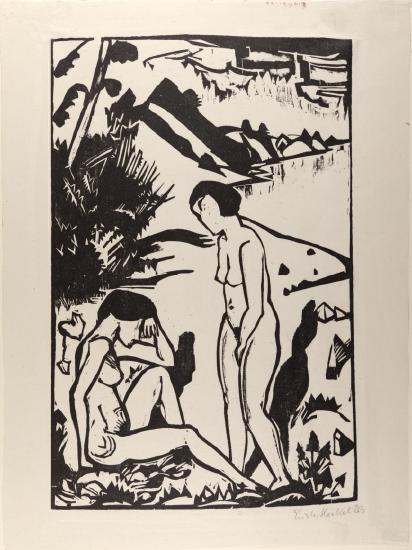

They found an antidote to modernity in a retreat to a pre-modern state of nature, as embodied in Erich Heckel’s print of two women bathing in a mountain landscape. The women’s nudity is a paradoxical mixture of eroticism and innocence. It combines the purity of humankind in Eden, when the body was not seen as sinful, with the presumed liberated sexuality of primitive people, which is denied to members of modern bourgeois society.

The intentional gaucherie (awkwardness) of Heckel’s style, another aspect of the work’s primitivism, is enhanced by the work’s medium. Woodcut was an old-fashioned technique of printmaking, but it was revived by the German Expressionists in part because of the natural materials it used and the crude simplicity of the images it tended to produce. It was markedly different from more recent and higher-tech printmaking processes such as etching, lithography, and photography.

Primitivism and colonialism

It is no coincidence that primitivist art was created and consumed by Western nations that were at the same time practicing colonialism: occupying and plundering much of Africa, Asia, and the Americas for labor and resources.

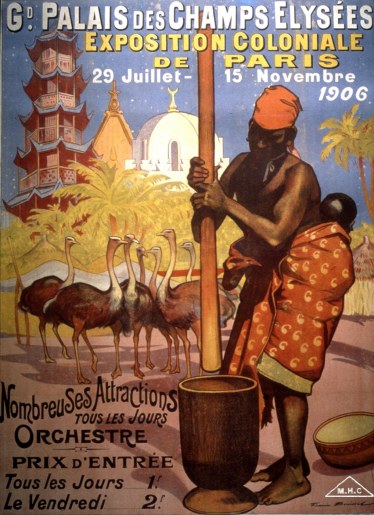

European fascination with these cultures was reflected in dozens of “colonial” exhibitions during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century. These often included what were essentially human zoos in which ethnic “specimens” would enact their cultural practices for curious spectators. The background of this poster for the 1906 Colonial Exhibition in Paris includes a pagoda, a North African mosque, and a Cambodian temple to display the widespread colonial holdings of France at the time. The foreground shows a living diorama of an African village, complete with mud and straw huts, ostriches, and a semi-nude woman with a child grinding grain against a backdrop of palm trees.

Although the work’s naturalistic style and depiction of labor are notably different from the artworks we have been examining, this exhibition poster singles out many of the same primitivist qualities lauded by modernist artists. These qualities seem designed to exemplify how much more “advanced” European culture is. The mud huts would have formed a stark contrast to the vast, modern iron-frame architecture of the Grand Palais in Paris, on the grounds of which the colonial exhibition was held. The woman’s task, grinding grain, was doubtless chosen in part to demonstrate her people’s capacity for hard physical labor. This was, however, also one of the first forms of industrialized labor in the West, where mills driven by wind and water power replaced hand grinding.

The poster thus shows the very primitive state of technology in this woman’s culture. Her semi-nudity also contrasts with the elaborate costumes worn by contemporary Parisian women, and would have promised a titillating attraction for the Belle Epoque visitors to the exhibition.

Even when these qualities are re-framed as positives — as antidotes to modern ailments such as overcrowded cities, runaway technology, emotional and sexual repression, and the loss of spirituality and of connection with nature — the stereotypes of primitivism are still problematic. Framing other cultures as “primitive” ultimately suggests the need for external aid and guidance, and thus helps to justify Western colonial practices. Primitivism is a peculiar mixture of admiration and denigration, appreciation and exploitation, elevation and repression. This is the paradox at the heart of the concept of primitivism; a paradox evident ever since the invention of the phrase “noble savage.”

Additional resources:

Explore MoMA’s 1984-85 exhibition, “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern

Formalism I: Formal Harmony

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

When James McNeill Whistler first exhibited his painting Nocturne in Black and Gold in 1877, the prominent Victorian art critic John Ruskin accused him of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Whistler sued Ruskin for libel, and over the course of the trial and beyond he articulated a defense of his work that is a famous example of a very influential modern theory of art called formalism.

Art as formal beauty

Whistler’s defense was that art is about beauty. Not the beauty of certain kinds of things — a swan, an idealized nude, or a picturesque landscape — but the beauty of certain color combinations in certain patterns: formal beauty. Denying that his Nocturne was an attempt to show an accurate view of a place, Whistler called it an “artistic arrangement,” and said that his “whole scheme was only to bring about a certain harmony of color.”\(^{[1]}\) What we are intended to appreciate, then, is not the painting’s likeness to a scene in nature (which happens to be a firework display over a river), but instead the asymmetric balance of the composition, the calligraphic quality of the painterly marks, and the way the orange flecks sparkle against the dark blue-greens.

Whistler frequently gave his paintings titles typical of musical compositions, such as symphony, harmony, arrangement, or nocturne, and listed their dominant color combinations as though they were the equivalent of a musical key. This analogy with music helps to divert our attention away from the subject matter of the painting to its form. When we hear a piece of instrumental music we do not expect it to imitate sounds from the real world. Instead, we just appreciate the way the sounds create pleasing harmonies. Why should visual art not be appreciated in the same way?

Art for art’s sake

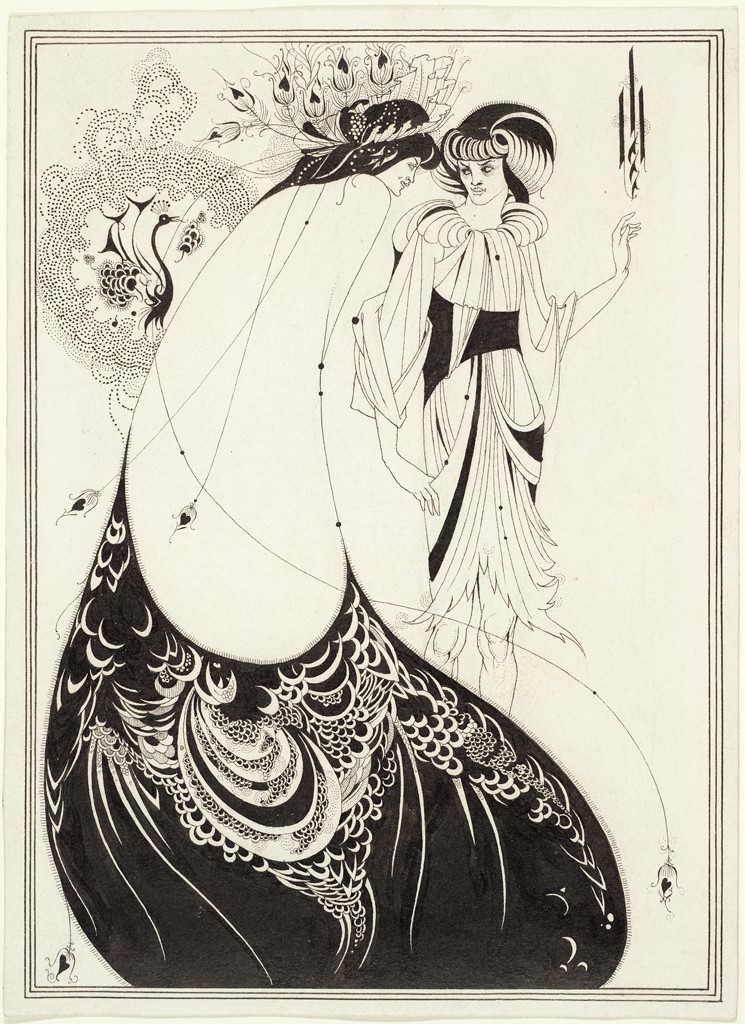

This theory of art was promoted by a late-nineteenth century literary and artistic movement called “Aestheticism,” which included Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde, and Aubrey Beardsley, as well as Whistler. Their motto, “art for art’s sake,” implicitly rejected the non-aesthetic goals commonly assigned to art, such as imitation of nature, moral instruction, spiritual exaltation, and emotional expression.

This idea of art was not entirely novel to the nineteenth century. The ancient Greeks had theorized that aesthetic harmony in both music and visual art resided in certain mathematical proportions. What is new here is the prominence that the Aesthetes granted this idea. For them, formal beauty was not just one of many potential goals for art; it was the pre-eminent and perhaps only quality the artist should strive for.

It was particularly shocking to Ruskin and Victorian England that the Aesthetes denied art’s role in improving public morality. Whistler scorned people who look “not at a picture, but through it,” to consider whether it will “better their mental or moral state.”\(^{[2]}\) He believed that art is not a vehicle for public reform any more than it is a means to reproduce the appearances of nature. We shouldn’t keep looking outside the painting for its purpose, but rather enjoy it for what it in fact is: a surface covered with harmonious arrangements of color.

Theories of art that concentrate on the sensory or material qualities of the work itself are called “formalist.” Note that formalism is not a historical style or movement like Impressionism or Cubism. Rather, it should be considered a basic theory that tries to explain what art is or should be.

Formalism and modern art

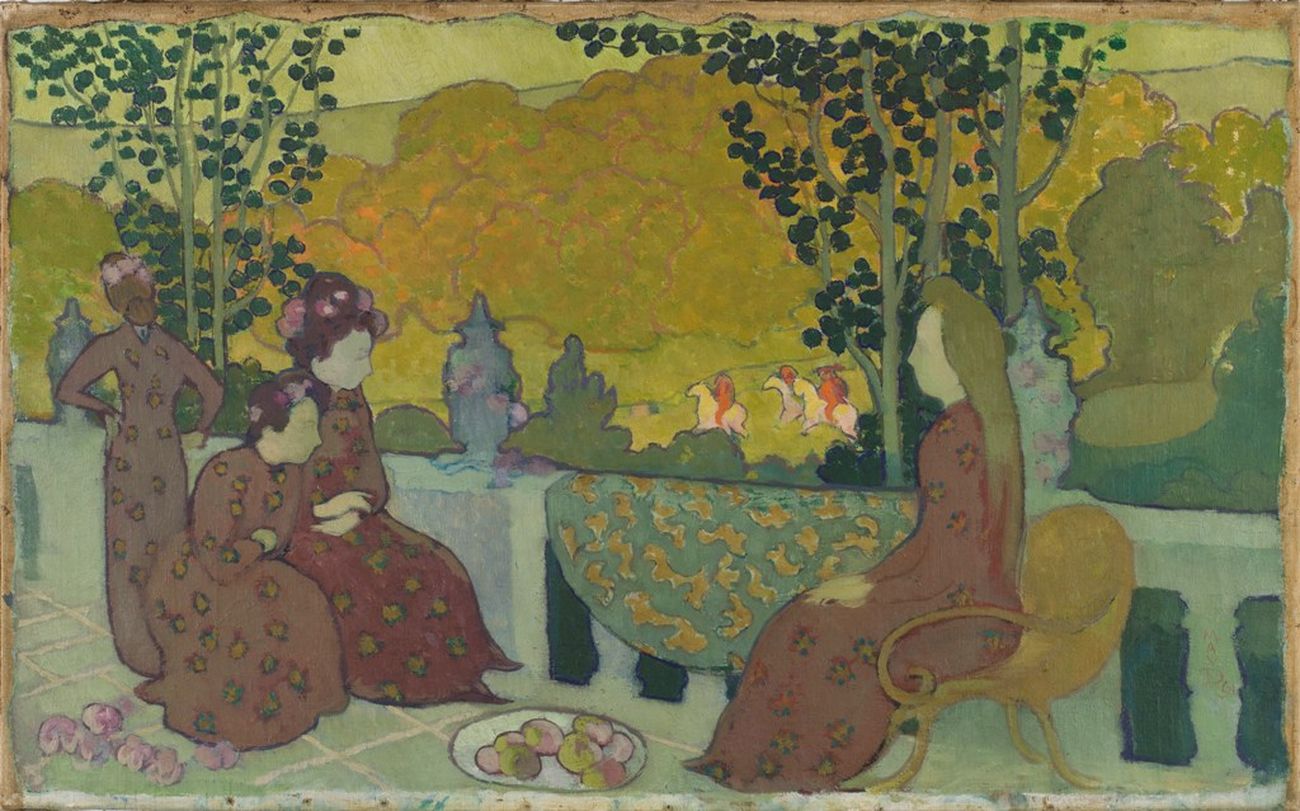

A number of modern movements emphasized the purely aesthetic qualities of art. In 1890 the Symbolist artist Maurice Denis famously asserted, “A painting — before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote — is essentially a flat surface covered with colors arranged in a certain order.”\(^{[3]}\) Correspondingly, Denis’s paintings read as surface patterns as much as (or even more than) representations of real-world spaces and objects.

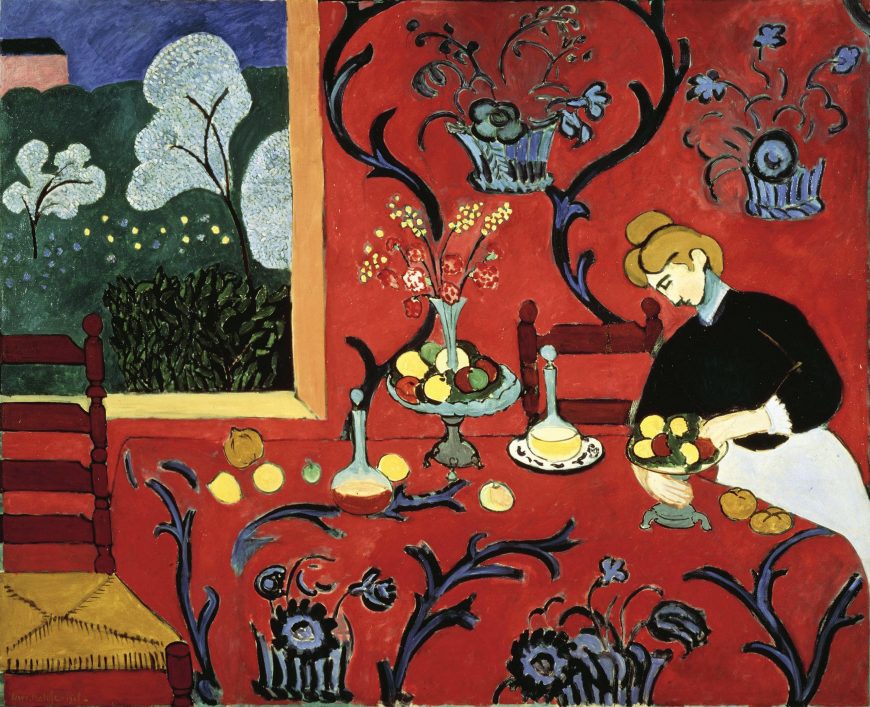

In another famous statement, the Fauve artist Henri Matisse confessed in his Notes of a Painter (1909), “my ambition is limited, and does not go beyond the purely visual satisfaction such as can be obtained from looking at a picture.”\(^{[4]}\)

Like Whistler, Matisse sought harmony in his works. He conveyed aesthetic pleasure not only through his choice of sensual and tranquil subjects — lounging nudes, picnics, dances, quiet domestic interiors — but also through form. In The Piano Lesson the painting’s nominal subject of a boy practicing the piano is just a pretext for showcasing a complex pattern of vivid colors against cool gray, and for contrasting rectilinear shapes with the swirling black tracery of the balcony railing and music stand.

Clive Bell and “Significant Form”

For many modern artists (including Matisse and Denis), a concern with formal harmony was paired with other goals, such as emotional expression, spirituality, and social agency. Formalist art theory was therefore mostly developed by art critics, rather than by artists themselves.

The English art critic Clive Bell articulated a formalist theory of art in his 1914 book Art. He claimed that the purpose of art is to evoke a particular kind of feeling that he called “aesthetic emotion.” This feeling is not caused by the subject, but by the form of the artwork:

What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto’s frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cézanne? Only one answer seems possible — significant form. In each, lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions.

Clive Bell, Art, (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1913), p. 8.

Note that Bell’s examples include architecture and craft as well as paintings and sculptures: any made object can be art if it exhibits significant form.

By the same token, not all paintings and sculptures qualify as art, according to Bell. In a painting such as William Powell Frith’s The Railway Station, the goal is accurate depiction. Certain anecdotes depicted in the work may arouse emotions, such as the mother embracing her child, but these are everyday emotions, not aesthetic emotions. The detail of the work may excite our admiration of the artist’s skill, but for Bell that skill was misdirected: true artists are dedicated to evoking aesthetic emotion through significant form.

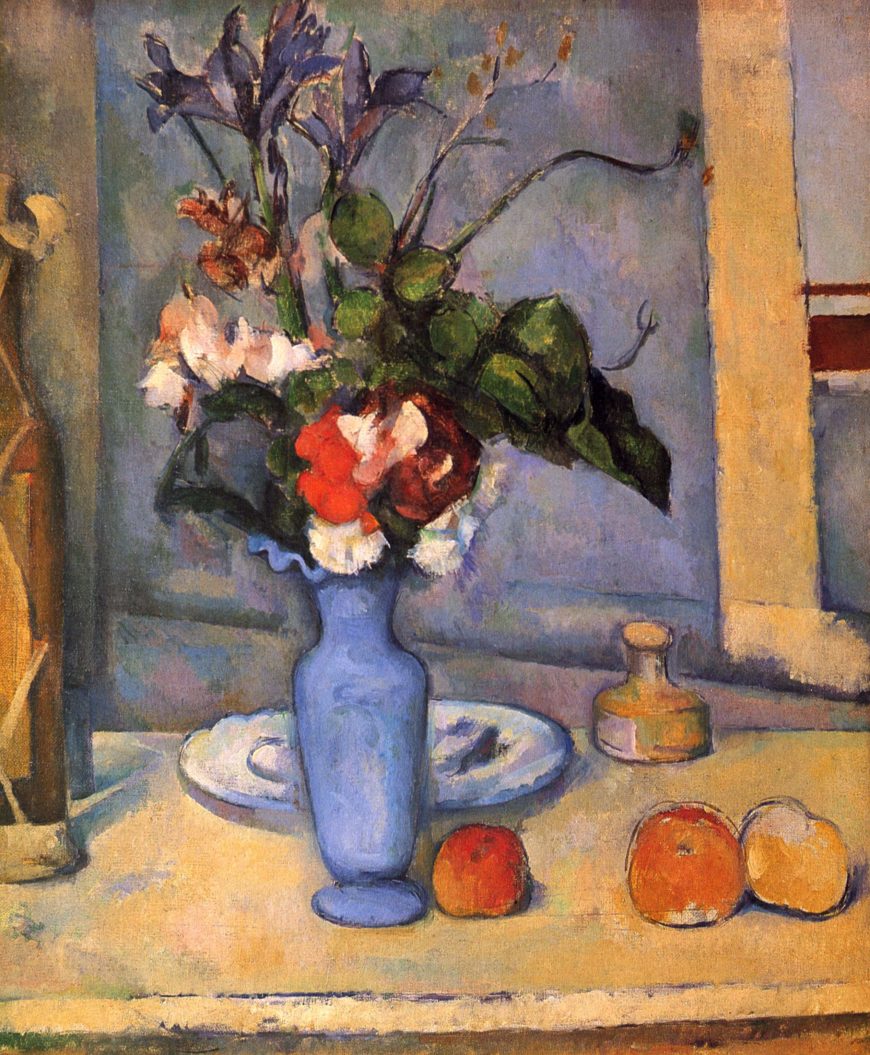

Bell admired works by non-Western and pre-Renaissance artists, whose lack of concern with representational accuracy freed them to use line, shape, and color to create significant form. In Bell’s view, certain recent artists such as Paul Cézanne had rediscovered art’s true purpose as evoking aesthetic emotions, rather than merely copying the appearances of nature.

The autonomy of art

One of the hallmarks of formalist art theory is the idea that the work of art should be experienced in itself, and not in relation to anything else. We should not compare the work with nature to judge how true-to-life it is. It makes no difference whether the work is a portrait of a king or pure abstraction, and we need not inquire about the social context in which the work of art was produced, whether it was second-century Rome, eighteenth-century Japan, or twenty-first century America. Everything we need to know about a painting is contained within the four edges of its frame. As Bell put it:

To appreciate a work of art, we need bring nothing from life, no knowledge of its ideas and affairs, no familiarity with its emotions. Art transports us from the world of man’s activity to a world of aesthetic exaltation …

Clive Bell, Art, (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1913), p. 25.

For its proponents, the formalist theory of art has the benefit of elevating art and the artist above everyday utilitarian and social concerns. For its opponents, however, art is and has always been part of life, and abstracting it from life’s concerns impoverishes its richness and diminishes its important social roles.

Thus, while it is certainly possible to analyze and appreciate this Matisse painting solely in terms of its formal qualities, to do so would require overlooking significant questions about gender roles, social class, consumption, and domesticity that are also raised by the work. In recent decades, these broader social concerns have dominated the approaches of most artists, critics, and historians, and purely aesthetic concerns have become less important.

There is another type of formalist art theory that arose slightly later and became dominant in the mid-twentieth century: one that asks viewers to focus not on formal harmony or a special “aesthetic emotion,” but instead on the properties of the materials or medium of which the work of art is made. We shall examine this aspect of formalism in Formalism II: Truth to Materials.

Notes:

- “The Action,” in James Abbot McNeill Whistler, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1892; reprint New York: Dover Publications, 1967), pp. 3, 8.

- “Mr Whistler’s ‘Ten O’Clock’” (1885), in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, p. 138.

- Maurice Denis, “Definition of neo-traditionism” (1890), in Jean-Paul Bouillon, ed., Le ciel et l’arcadie (Paris: Hermann, 1993), p. 5 (authors’ translation).

- Matisse, “Notes of a Painter,” sixth paragraph.

Formalism II: Truth to Materials

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

“Formalism” is the name given to a theory that locates the nature and purpose of art in its sensory, material properties or form. For the visual arts, this includes line, shape, color, composition, texture, and so on. In Formalism I we examine a branch of formalist art theory that sees the purpose of art as evoking specifically aesthetic feelings, such as beauty or harmony. Here, we turn to a later development of formalism that called for “truth to materials.”

Truth to materials

In this branch of formalist art theory, the primary focus remains on the material qualities of the artwork, but instead of asserting that the artist’s goal is formal harmony, some artists and critics begin to talk about art as a means of understanding and displaying the properties of the materials of which it is made.

Ever since the Renaissance, artists in pursuit of naturalism had attempted to transcend the limitations of their media. Sculptors such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini excelled at making hard, cold marble look like soft flesh and fluttering drapery.

Certain artists in the twentieth century, by contrast, chose to showcase rather than disguise their materials. In 1934, British sculptor Henry Moore put it this way: “Every material has its own individual qualities … Stone, for example, is hard and concentrated and should not be falsified to look like soft flesh … It should keep its hard tense stoniness.”\(^{[1]}\) This imperative to be ‘true to one’s materials’ became an important critical tenet of twentieth-century art.

There are nineteenth-century roots to this idea, especially in architecture and design theory. The Victorian art critic John Ruskin made it an imperative for artists and craftspeople to “honor” their materials:

The workman has not done his duty, and is not working on safe principles, unless he … honours the materials with which he is working … If he is working in marble, he should insist upon and exhibit its transparency and solidity; if in iron, its strength and tenacity; if in gold, its ductility …\^{[2]}\)

In part, this insistence on truth to materials arose in the nineteenth century because of the proliferation of low-quality, mass-produced manufactured goods. In furniture and interior decoration, cheap materials were often disguised to make them look more expensive, such as faux marbling, wood veneers, or imitation copper patina. Ruskin called such falsified use of materials “illegitimate and debased,” [3] terms that reflect a moral imperative to use materials honestly.

Constructivism and the Bauhaus

The formalist principle of “truth to materials” was taken up in the second and third decades of the twentieth century by art and design movements such as Constructivism and the Bauhaus.

In this Russian Constructivist sculpture by Vladimir Tatlin, the materials themselves are the primary focus of the artist. An old wood panel is used as a tack board for scraps of found materials: leather, wire, stamped tin, a wooden dowel, and offcuts of copper sheet. Each of these materials has been manipulated in ways that show off its properties: the wood is pitted and weathered, the coarse-grained leather is stretched tautly between brass tacks, the copper sheet has been cut and bent into sharp, edgy planes, and the wire has been curled into tight spirals. There is no moral lesson or symbolism here; it is simply a sampler of materials displayed in ways that demonstrate their material properties.

Influenced by ideas coming out of Russia, the German design school Bauhaus instituted a rigorous introductory course to familiarize students with basic design principles and the properties of various materials. A typical exercise in Josef Albers’ class would help students to understand the qualities of paper through open-ended, independent experimentation, “a playful tinkering with the material for its own sake.” [4] In the resultant student projects, we can see folds, rolls, cuts, tears, corrugation, notching — all sorts of ways of working with paper to develop an understanding of its nature and potential as a constructive medium.

Greenbergian formalism

In the mid-twentieth century, the influential American art critic Clement Greenberg consolidated the entire history of modern art around this idea of truth to materials. Attempting to account for what, if anything, such diverse-seeming styles as Impressionism, Cubism, Constructivism, and Abstract Expressionism had in common, Greenberg concluded that all modern artists were attempting to be true to their materials, and more specifically to “purify” their respective media.

For Greenberg, each artistic medium, such as painting, sculpture, or literature, has an “area of competence” that it should stick to, as determined by its material properties:

It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique to the nature of its medium. The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art. Thereby each art would be rendered ‘pure’…\(^{[5]}\)

For example, literature is a temporal medium, since it is read sequentially, word-by-word and page-by-page. Hence story-telling, the development of events and characters through time, is within its area of competence.

A painting, by contrast, can only with great difficulty tell stories; it struggles to show more than a single moment in a single action. Hence narrative is not really part of painting’s area of competence. The whole category of “history painting” (art depicting stories from history, literature, or mythology) is counter to what Greenberg believed was the true vocation of painting.

In addition, it is only with great difficulty that painting shows a third dimension. By using techniques such as chiaroscuro to suggest volume and perspective to suggest space, artists can give an illusion of a third dimension — but it is only an illusion, and it falsifies painting’s true nature. Volume is properly within sculpture’s area of competence, and space is within architecture’s.

For Greenberg, painting’s area of competence lies in three factors: the flatness of the surface, the shape of the support (typically a rectangular canvas), and the properties of the pigment or color that is put upon that surface. Of these three, Greenberg argued, the most unique to painting is flatness; consequently, he saw the entire history of modern painting as a gradual embrace of painting’s flatness.

In Greenberg’s view, modernist painting began with Edouard Manet’s compression of space and use of a frontal light source that minimized chiaroscuro and denied the illusion of mass. Cubism continued this development, its slightly-angled facets, spread across the entire surface of the painting, defining only a very shallow space. The mid-century American modernists of Greenberg’s own time finally embraced the true identity of painting as a flat surface covered with a colored design.

Backlash

Greenberg had enormous influence on art in the mid-twentieth century, as some artists attempted to fulfill his exacting criteria for formalist purity. Today, however, Greenberg’s rigorous version of formalist art theory is almost completely discredited. Socially-conscious artists, critics, and art historians object to the way the formalist theory of art separates art from its social context. History, politics, spirituality, expression — all of these are irrelevant to the formalist theory of art.

One could do an exclusively formalist reading of Picasso’s Guernica, and consider how the artist tastefully contrasted organic, curving shapes with hard-edged, angular shapes; or discuss how he rejected perspective and minimized modeling to assert the flatness of the painting’s surface. However, to do so would be to ignore the clear desperation of the gesticulating characters, the horror of the event, the classical references, the powerful expression, and above all the urgent political message.

Formalism as a totalizing theory of art the way Clive Bell or Clement Greenberg imagined is largely an historical footnote. However, it is an important footnote, and ideas of formal harmony and truth to materials had a great deal of influence for many nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists. It is just as impossible to fully understand the history of modern art without acknowledging formalism, as it is to understand modern art using only formalism.

It is also important not to confuse the theory of formalism with the technique of formal analysis. With rare exceptions, works of art have a physical presence and formal properties that are integral to what they have to say, and we need to have a keen eye to discern those properties and describe how they affect the work’s meaning(s). While formalism may be dead, formal analysis remains an essential skill for the study of art.

Notes:

- Henry Moore, “Statement for Unit One,” in Herbert Read, ed., Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture (London, 1934), p. 29.

- John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, vol. 2 (London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1953), appendix 12: Modern Painting on Glass, pp. 391-92.

- Ibid.

- Josef Albers, “Teaching Form through Practice,” Bauhaus vol. 2 no. 3 (1928), translated by Frederick Amrine, Frederick Horowitz, and Nathan Horowitz, 2005, albersfoundation.org/teaching...-albers/texts/ (accessed 13 February 2020).

- Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting” (1960), in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1900-1990 (Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge, MA, 1997), p. 755