16.4: England

- Page ID

- 108758

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Four styles of English medieval architecture at Ely Cathedral

by Meg Bernstein

Four styles of English medieval architecture

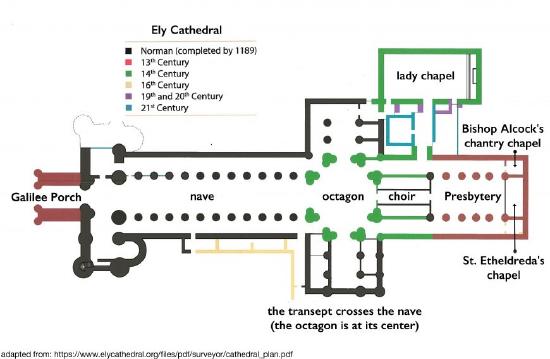

Ely Cathedral, like nearly all medieval English cathedrals, saw many different phases of construction. Major building projects in the Middle Ages were both expensive and time-consuming, so renovations and additions were made piecemeal rather than all at once. The long period of time means that by looking at Ely, we can get a sense of each of the most important medieval English architectural styles, all in one building: Romanesque, in the nave; Early English, in the presbytery; Decorated, in the tower and Lady Chapel; and Perpendicular, in the eastern chantry chapels. See the plan in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

A saint in the marshes

Ely Cathedral, sometimes referred to as “the ship of the Fens,” is a massive building rising up from the flat, marshy fenland of East Anglia. It is visible from many miles away like a lone ship on a calm sea. Ely’s history began in the seventh century, when an Anglo-Saxon princess named Æthelthryth, or Etheldreda, made a holy vow of virginity. When she was married for political reasons, she fled her husband and founded a nunnery on the Isle of Ely. In Etheldreda’s time, Ely was an island surrounded by marshes (drained later, in the seventeenth century), and the place takes its name from the eels that dwelled in these swampy waters.

Etheldreda died just seven years after founding her nunnery. When her body was translated, or ceremonially moved, from its original location in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) fourteen years later, it was found to be incorrupt and it was put into a “new” sarcophagus—actually a reused one from an old Roman settlement nearby. A cult developed around Etheldreda, who became a saint (the common name for Etheldreda is St. Audrey).

Etheldreda’s nunnery was raided by Danish invaders in 870. Whether the relics of Etheldreda survived the raid is an open question, but the author of the twelfth-century text, the Liber Eliensis (Book of Ely), detailed stories of the continued power of Etheldreda’s relics, possibly intended to suggest that they had not been destroyed. Relics were very important objects in the Middle Ages, lending prestige to the churches where they were held, and drawing pilgrims, who would come seeking miracles. The existence of Etheldreda’s relics was therefore very important for the identity of the church at Ely, where in 970, with royal patronage, the church was refounded as a Benedictine monastery.

The Romanesque (Norman) building

Though it had been the site of Christian worship for hundreds of years prior to 1082, little is known about the architecture of Ely before this date, when the first Norman abbot of Ely initiated the construction of a new church for the monastery. The foundations were laid out by a man in his 80s named Abbot Simeon who had previously been prior of the important monastic community of Winchester, in the south of England, where his brother, Walchelin, was bishop. Simeon and his brother had orchestrated a building campaign in Winchester that was still underway when Simeon came to Ely, and that in-progress church served as inspiration for much of the Ely building program.

Simeon’s building plans at Ely began in the east end with the choir and transepts (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). This is typical for churches, since their primary liturgical functions commonly take place in the east end of the church, oriented towards Jerusalem. This part of the church exemplifies the Romanesque style brought from Normandy after the Norman Conquest in 1066. It was completed in two different phases, which we can tell from the new decorative forms that appear on some of the capitals of the columns of the transepts, which were built later than the others.

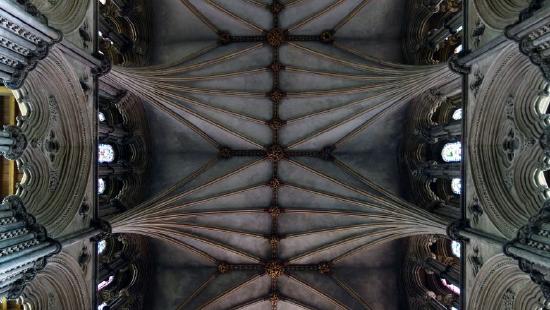

Work on the nave was begun subsequently, and the south side was completed around 1109, when Ely was officially elevated to the status of a cathedral (see Figures \(\PageIndex{6}\) and \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Ely’s nave and transepts were some of the first spaces in England to display alternating forms of compound piers. This alternation adds visual rhythm, and diffuses the heaviness of these massive stone forms.

Like most Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, Ely’s nave elevation has three stories (see Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). The nave arcade with its alternating piers is on the ground floor. Above this is a gallery with double-light openings, or double, windowless arches, each pair set within a larger arch that mirrors the corresponding arch on the lower level. The third level is a clerestory with triplet openings. The tremendous thickness of the walls--a distinguishing feature of the Romanesque--is balanced by the proliferation of openings as one’s eyes travel upward. The viewer gets the sense that the building becomes lighter and brighter as it soars heavenward.

Late Romanesque and Early English Gothic

The west tower that tops the cathedral’s main entrance was built at the end of the twelfth century, towards the end of the Romanesque period in England.

Experiments in the Gothic style brought over from France had already begun to take hold in England—particularly at Canterbury Cathedral and the northern Cistercian monasteries. At Ely, though, the tower still exhibits round Romanesque arches instead of the pointed arches that are a hallmark of Gothic architecture (see Figures \(\PageIndex{8}\) and \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

The exterior is covered almost completely in blind arcading, an English specialty that stands in stark contrast to French medieval architecture, which prefers little extra surface decoration. Below the tower, we see a monumental entrance with blind pointed arches, which was added a bit later in the Early English Gothic style, showing how this new style was rapidly spreading across England during this time (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)).

At the other end of the building, the presbytery was extended eastward in the 1230s and 1240s. In style, it draws from the nave of Lincoln Cathedral, completed just a decade or so earlier. With engaged colonnettes of Purbeck marble and white limestone, as well as complex rib vaults, it reflected the most fashionable architecture of the time. Then, as now, architectural styles came and went quickly, and the wealthiest and most powerful—such as the Bishop and diplomat Hugh of Northwold, who financed the new presbytery—had the means to stay current.

Eastern extensions were popular at this time to provide more room for the shrines of saints, like Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral, or, at Ely, the shrine of Etheldreda. The presbytery was large enough to accommodate the many pilgrims who came to Ely to venerate the saint, and brought important income to the church and surrounding area. Having a highly-decorated space made this holy destination even more desirable.

Ely Cathedral in the Decorated Style

In 1321, a new chapel was begun north of the presbytery, which would eventually become one of the most beautiful and artistically innovative of the English Gothic period. But in the early morning hours of February 13, 1322, just as the monks were finishing their morning prayers, disaster struck. The crossing tower of the cathedral collapsed, crushing parts of the choir, and construction on the chapel had to stop.

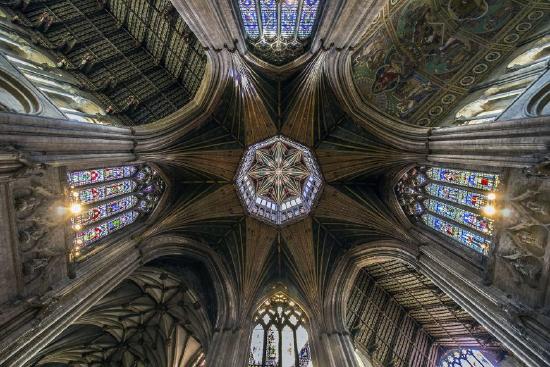

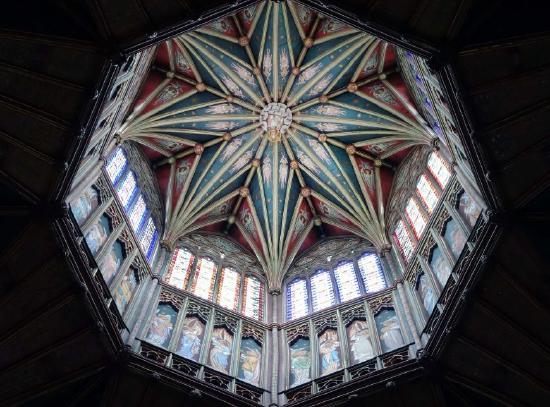

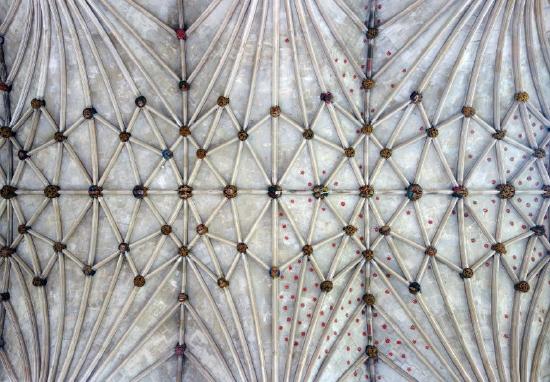

Though this collapse was devastating, it made room for one of the most remarkable structures of the English Middle Ages. Alan of Walsingham, sub-prior and sacrist of Ely, quickly initiated the building of a new tower—a tall, octagonal structure (often referred to as “the Octagon”) surmounted by a tower made of timber clad with lead (see Figures \(\PageIndex{14}\) and \(\PageIndex{15}\)). This type of tower is called a lantern because it is pierced to allow light in. Vaults with tiercerons spring from the base of the Octagon, creating a star-like effect when one looks up.

In the supporting structure below, Etheldreda was commemorated with capitals depicting scenes from her life (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)). These include her marriage to Igfrid, and her rest on the way from Northumberland to Ely. The Octagon, from floor to the central roof boss, is 142 feet tall, the same height as the Pantheon in Rome. This correspondence may have been intentional, since the Octagon is like a Gothic version of the Pantheon’s incredible dome, and the tower above it delivers light throughout, like the opening of the Roman temple.

Once the Octagon was completed, attention was turned back to the Lady Chapel (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)). A Lady Chapel is a space dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and this one is especially clear in its depiction of her life and miracles. The chapel, built in the Decorated Style , is rectangular, and its elevation is composed of a dado and clerestory. A series of niches encircle the room, forming the dado.

Each niche is protected with a nodding ogee canopy and ornamented with relief sculpture relating to the Virgin (see Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)). It has been observed that the sculptural niches of the dado have a vulvular shape, perhaps not coincidental given that the chapel celebrates the Virgin Mary, whose chief contribution to Christian history was giving birth to Jesus.

The Lady Chapel was interrupted by the collapse of the central tower, and its progress may have been troubled again by the Black Death, which struck England in 1348. On the western side of the chapel, the nodding ogees of the dado flatten, and the diaper-work is halted (see Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\)). The vault fits uneasily on the chapel. Scholars suspect that some of the sculptors and masons at Ely may have fallen victim to the plague, leaving the lavish project to be completed by their less adept colleagues (see Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\)).

Iconoclasm in the Ely Lady Chapel

Although the Ely Lady Chapel is one of the most beautiful interiors of English medieval art, it’s also one of the most heavily destroyed. During the English Reformation, the sculptures were mutilated because religious imagery was thought to be idolatrous. The images were taken from their niches, and the colorful stained glass that would have filled the windows was destroyed (see Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)). Some sculpture remains in the life of the Virgin series on the dado, but many have been stripped of their heads or more. Traces of polychromy remain, but are but a pale shadow of the formerly brilliant space.

The end of the Middle Ages

After the Black Death, a final style of the English Middle Ages emerges as the primary mode of building. This is called the Perpendicular Style because, unlike the flowing, undulating curves of the Decorated Style that preceded it, it emphasizes straight lines and vertical projections. The Perpendicular Style took hold in the second half of the fourteenth century, and continued through the remainder of the Middle Ages—almost two hundred years!

Bishop Alcock’s chantry chapel was built in the Perpendicular Style between 1488 and 1500 (see Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\)). A chantry chapel is a space devoted to praying for an individual or a family in order to shorten their time in purgatory. Purgatory was understood to be a fiery place where souls went after death, but unlike hell, one could eventually leave purgatory after serving the required amount of time necessary for sins committed during life (see one artist's conception of Purgatory in Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\)). A reduction of one’s sentence in purgatory could be achieved, either during life from the acquisition of indulgences, or in death if one’s loved ones or the executors of their wills prayed for them and ensured that masses were said in their honor.

Alcock is likely to have planned the chapel himself—he had been the Controller of the Royal Works and Buildings under King Henry VII. The chapel is cordoned off from the north aisle with a microarchitectural screen with statue niches that are now empty. Though this screen is extremely intricate and beautifully carved, it doesn’t quite fit in the space allotted for it. Prior to becoming bishop of Ely, Alcock had held the same post at Worcester Cathedral. It is thought that the chapel may have been planned for a large space there, but was instead jammed into tighter accommodations at Ely. Within the chapel is Alcock’s tomb, in a niche, and an altar so that Masses could be said for his soul. Alcock’s memory was also made explicit with the use of his rebus with a cock, or rooster, atop a globe, and his coat of arms, three cocks.

A ship of four styles

The “ship of the Fens” is a wonderful example of the evolution of English architectural style in the Middle Ages: from Romanesque to Early English Gothic, Decorated, and Perpendicular. The people who built churches in the Middle Ages wouldn’t have thought of themselves as building in these styles, however—these are names given by historians in the nineteenth century to describe them retrospectively. The builders themselves would have thought of what they were building simply as “current.” Although Etheldreda sought refuge her marriage in the quiet, eel-filled marshes of Ely, the Middle Ages saw this site develop into a far more elaborate space than she could possibly have imagined.

Articles in this section:

- Meg Bernstein, "Four styles of English medieval architecture at Ely Cathedral," in Smarthistory, October 26, 2018 (CC BY-NC-SA)