16.3: Holy Roman Empire

- Page ID

- 108756

Röttgen Pietà

by Dr. Nancy Ross

An emotional response

It is hard to look at the Röttgen Pietà and not feel something—perhaps revulsion, horror, or distaste (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). It is terrifying and the more you look at it, the more intriguing it becomes. This is part of the beauty and drama of Gothic art, which aimed to create an emotional response in medieval viewers.

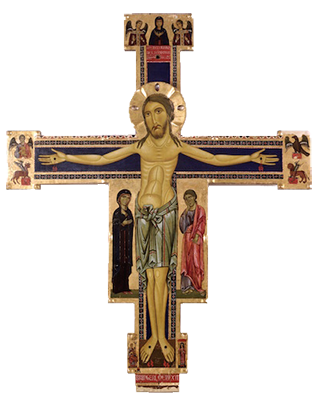

Earlier medieval representations of Christ focused on his divinity (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). In these works of art, Christ is on the cross, but never suffers. These types of crucifixion images are a type called Christus triumphans or the triumphant Christ. His divinity overcomes all human elements and so Christ stands proud and alert on the cross, immune to human suffering.

Triumphant Christ/Patient Christ

In the later Middle Ages, a number of preachers and writers discussed a different type of Christ who suffered in the way that humans suffered. This was different from Catholic writers of earlier ages, who emphasized Christ’s divinity and distance from humanity.

Late medieval devotional writing, from the 13th-15th centuries, leaned toward mysticism and many of these writers had visions of Christ’s suffering. Francis of Assisi stressed Christ’s humanity and poverty. Several writers, such as St. Bonaventure, St. Bridget of Sweden, and St. Bernardino of Siena, imagined Mary’s thoughts as she held her dead son. It wasn’t long before artists began to visualize these new devotional trends. Crucifixion images influenced by this body of devotional literature are called Christus patiens, the patient Christ (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

The effects of this new devotional style, which emphasized the humanity of Christ, quickly spread throughout western Europe through the rise of new religious orders (the Franciscans, for example) and the popularity of their preaching. It isn’t hard to see the appeal of the idea that God understands the pain and difficulty of being human. In the Röttgen Pietà, Christ clearly died from the horrific ordeal of crucifixion, but his skin is taut around his ribs, showing that he also led a life of hunger and suffering.

Pietà statues appeared in Germany in the late 1200s and were made in this region throughout the Middle Ages. Many examples of Pietàs survive today. Many of those that survive today are made of marble or stone but the Röttgen Pietà is made of wood and retains some of its original paint. The Röttgen Pietà is the most gruesome of these extant examples.

Many of the other Pietàs also show a reclining dead Christ with three dimensional wounds and a skeletal abdomen (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). One of the unique elements of the Röttgen Pietà is Mary’s response to her dead son. She is youthful and draped in heavy robes like many of the other Marys, but her facial expression is different. In Catholic tradition, Mary had a special foreknowledge of the resurrection of Christ and so to her, Christ’s death is not only tragic. Images that reflect Mary’s divine knowledge show her at peace while holding her dead son. Mary in the Röttgen Pietà appears to be angry and confused. She doesn’t seem to know that her son will live again. She shows strong negative emotions that emphasize her humanity, just as the representation of Christ emphasizes his.

All of these Pietàs were devotional images and were intended as a focal point for contemplation and prayer. Even though the statues are horrific, the intent was to show that God and Mary, divine figures, were sympathetic to human suffering, and to the pain, and loss experienced by medieval viewers. By looking at the Röttgen Pietà, medieval viewers may have felt a closer personal connection to God by viewing this representation of death and pain.

In this video, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris discuss what they call "a transitional moment in Italian painting," comparing two late medieval tempera panels showing Jesus on the cross, both housed in the Uffizi Museum in Florence, Italy. Whereas the earlier one (Christ Triumphant [Christus triumphans], also known as the 432 Cross, c. 1180–1200) shows a calm, triumphant, and essentially uninjured Jesus, the later one (Crucifix and Eight Stories from the Passion [Christus patiens], also known as the 434 Cross, c. 1240) shows emphatic, physical suffering.

Smarthistory, "From transcendent to human: The Crucifixion c. 1200"Articles in this section:

- Dr. Nancy Ross, "Röttgen Pietà," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "The Crucifixion, c. 1200 (from Christus triumphans to Christus patiens)," in Smarthistory, December 18, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)