15.4: Late Byzantine

- Page ID

- 108700

Late Byzantine church architecture

by Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

Constantinople reclaimed

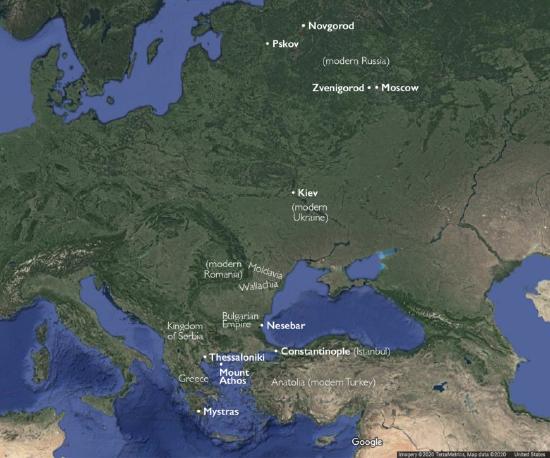

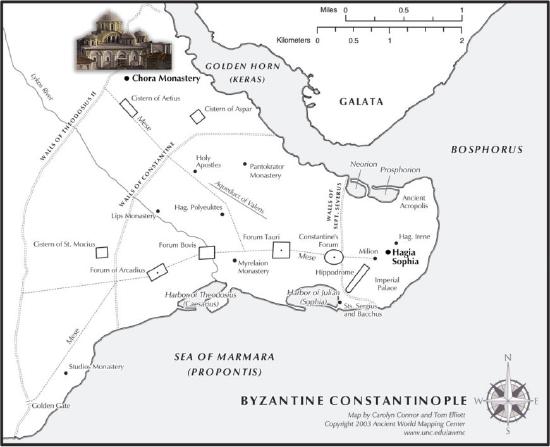

In 1204, crusaders of the Fourth Crusade sacked and occupied the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, beginning the period of the Latin Empire (the Byzantines referred to western Europeans—faithful to the pope of Rome—as “Latins” or “Franks” during this period). But in 1261, the Empire of Nicaea, a Byzantine successor state, retook Constantinople and crowned Michael VIII Palaiologos as their new emperor, ending the period of the Latin Empire (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

The “Palaiologan Renaissance” in Constantinople

In Constantinople, church architecture was revived after the reconquest of the city in 1261. Most constructions represent additions to existing monastic churches, probably following the model of the triple church at the Pantokrator monastery (read more about the Pantokrator monastery; see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

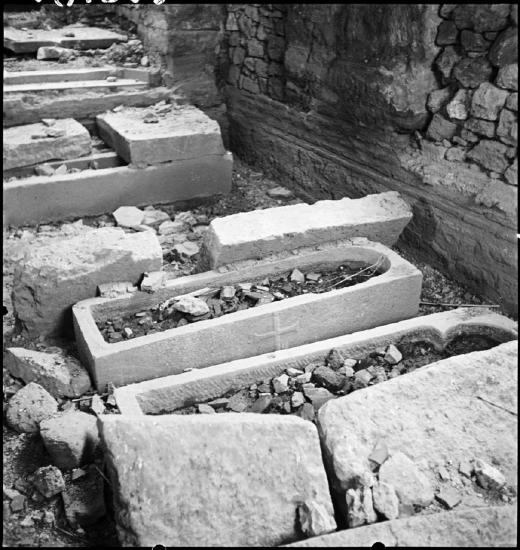

In all, there is little attempt at visual integration (see Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). An impressive funeral chapel as a setting for privileged burials was a standard feature, along with additional narthexes or ambulatories, equipped for burials. The building complexes are distinguished by an irregular row of apses along the east façade, topped by an asymmetrical array of domes. The parts read individually, with a marked contrast between the Middle and Late Byzantine forms.

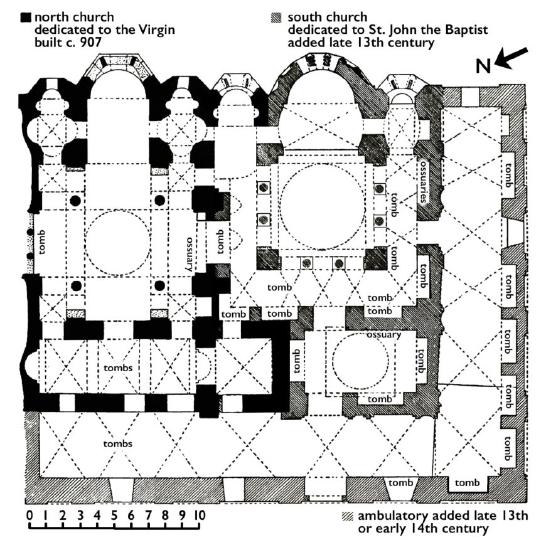

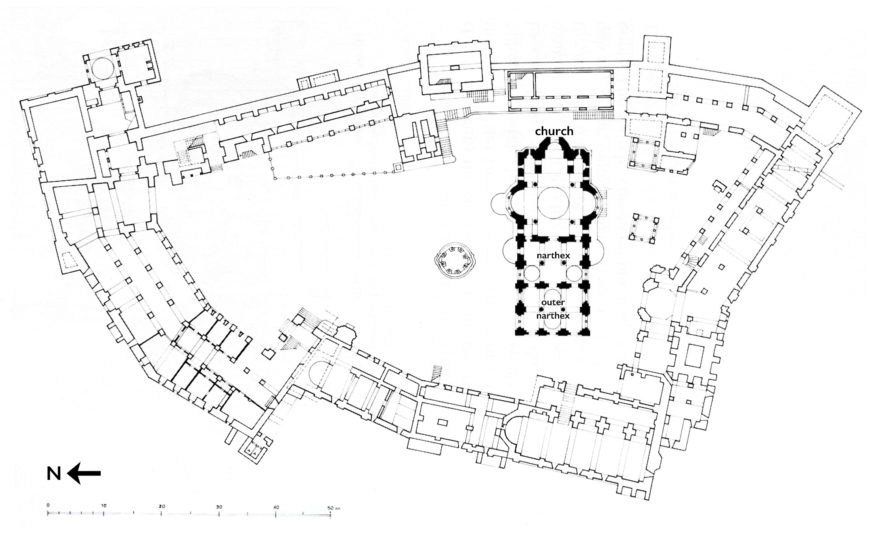

The Mone tou Libos

The monastic complex known as Mone tou Libos (first established c. 907; see Figure \(\PageIndex{3\6}\)), for which the typikon survives, was expanded c. 1282-1303 by the widow of Michael VIII with the addition of an ambulatory-planned church equipped with arcosolia, where the early members of the Palaiologos imperial family were buried.

In a second, closely related building campaign, an outer ambulatory was added along the south and west of the complex, with numerous additional arcosolia tombs.

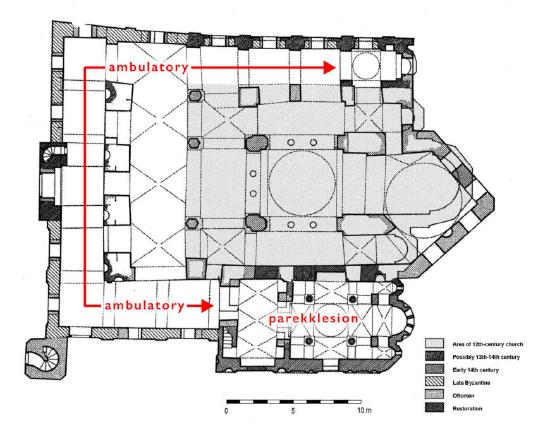

The Theotokos Pammakaristos

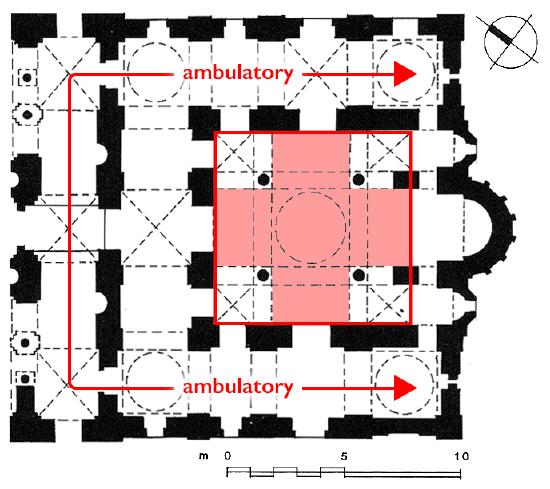

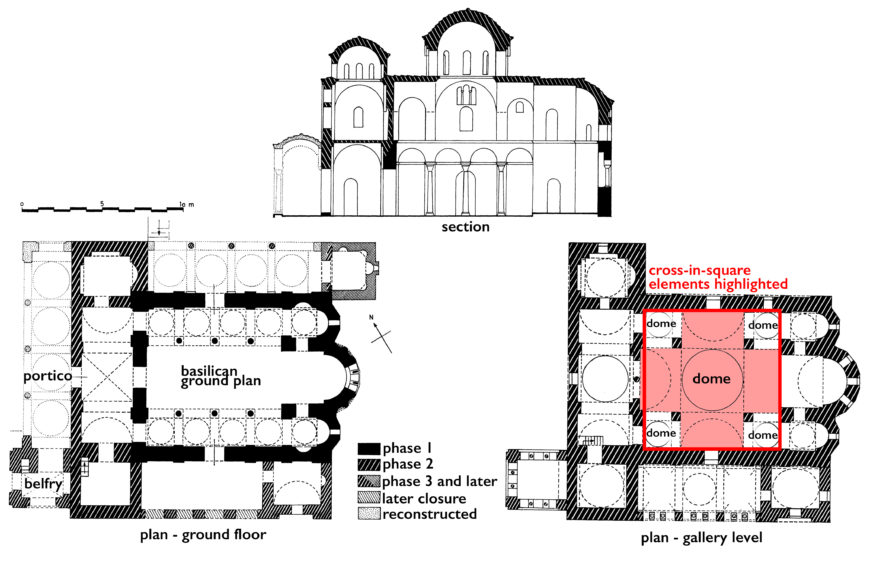

At the Theotokos Pammakaristos, a twelfth-century ambulatory-plan church was expanded in several stages, with chapels, a belfry, and an outer ambulatory (see Figures \(\PageIndex{7}\) and \(\PageIndex{8}\)).

Most important is the south parekklesion, a tiny but ornate cross-in-square chapel, built c. 1310 to house the tomb of Michael Glabas Tarchaniotes (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

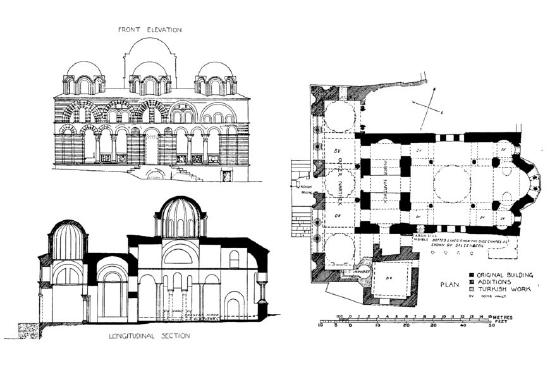

Vefa Kilise Mosque

The building now known as the Vefa Kilise Mosque was also expanded in several phases, with the addition of a two-stored annex, a belfry, and a three-domed, porticoed exonarthex with burial vaults beneath its floor.

The Chora Monastery

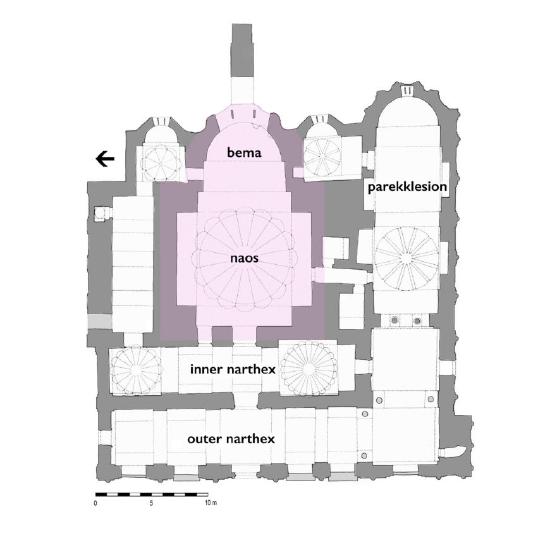

Of the Palaiologan monuments in Constantinople, the most important to survive is the Chora Monastery, where the additions uniquely represent a single phase of construction.

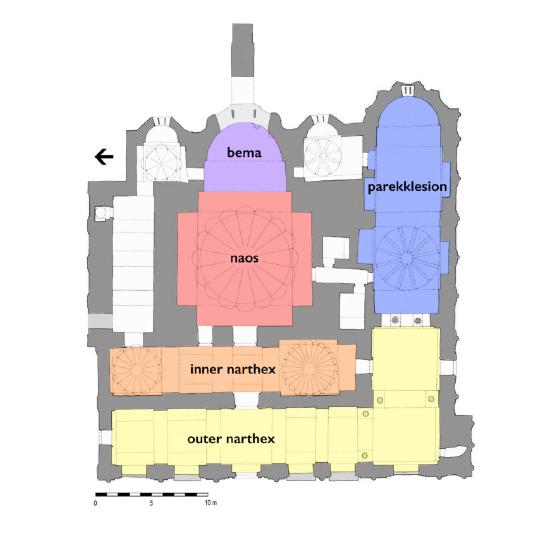

Restored and lavishly decorated by the statesman and scholar Theodore Metochites c. 1316-21, the twelfth-century naos was enveloped with a two-storied annex to the north, two broad narthexes to the west—the inner topped by two domes, the outer opened by a portico façade, and a domed funeral chapel or parekklesion to the south, with a belfry at the southwest corner.

In all of the Palaiologan complexes, complexity is more important than monumentality in the visual expression, and the new portions may be understood as a response to history, an attempt to establish a symbolic relationship with the past. By 1330, however, the short-lived “Palaiologan Renaissance” had ended in the capital, at least in terms of major church construction.

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki also saw the construction of numerous churches in the Late Byzantine period.

Ambulatory-plan churches

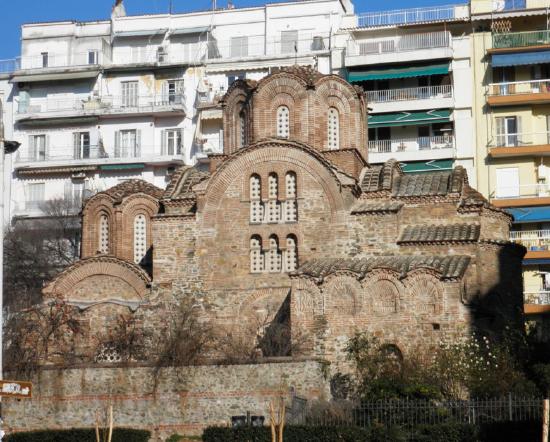

At H. Panteleimon, H. Aikaterini, and H. Apostoloi, all late thirteenth or early fourteenth century in date, an attenuated cross-in-square core was enveloped by a pi-shaped ambulatory.

Topped by multiple domes and opened by porticoes, the auxiliary spaces included subsidiary chapels.

Although their counterparts in Constantinople clearly served for burials, the functions of the ambulatory in Thessaloniki are less evident. Several simpler, unvaulted churches survive from the same period.

Profitis Elias

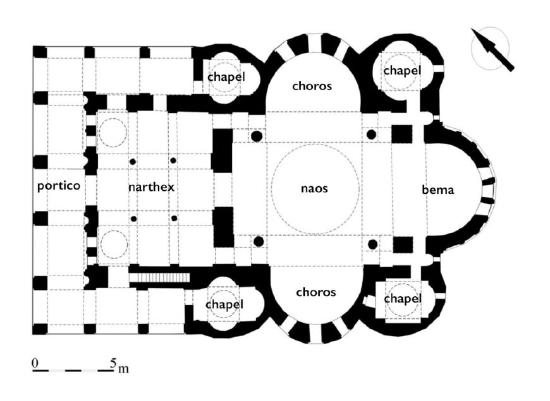

The Profitis Elias, built c. 1360 on an Athonite plan (with choroi and subsidiary chapels), demonstrates the enduring vitality of architecture in the city.

Mystras

Mystras (in the Peloponnese in Greece) emerged as a major Byzantine political center with the expulsion of the Latins in the mid-thirteenth century (following their occupation of the region since the time of the Fourth Crusade).

Hodegetria Church at Brontochion Monastery

Several churches of the so-called “Mystras type” (named for their location in Mystras, Greece) combine a basilican ground plan with a cross-in-square, five-domed gallery, the whole enveloped by porticoes, a belfry, and additional subsidiary spaces.

The Hodegetria (or Aphentiko) church at the Brontochion monastery, built c. 1310-22, betrays evidence of an ad hoc creation, begun as a simple cross-in-square church.

Pantanassa monastery

The type is repeated as late as 1428 in the church of the Pantanassa monastery.

Churches of the octagon-domed church and cross-in-square types were also constructed in this period (read more about octagon-domed churches). Architectural detailing suggests close connections with both Constantinople and Italy.

Bulgaria

Perhaps most significant in this period is the emergence of neighboring powers as creative centers of architecture. Bulgaria remained closest to Byzantium in its architectural developments.

The Pantokrator and Sv. Ivan Aliturgetos at Nesebar

Although more robust in terms of their surface decoration, the late churches of Nesebar, for example, follow the construction techniques and façade ornamentation of Constantinople. The coastal town passed repeatedly between Byzantine and Bulgarian control.

The churches of the Pantokrator and Sv. Ivan Aliturgetos date to the mid-fourteenth century and are most distinctive for their colorful exteriors, combining brick and stone decoration with glazed ceramic disks and rosettes.

Serbia

Medieval Serbia experienced some western European influence from the Dalmatian coast in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (as at Sopoćani, c. 1265), but as close ties and political rivalry with Byzantium developed in the fourteenth century, Serbian architecture generally followed Byzantine developments, importing both ideas and masons.

Gračanica Monastery

In many ways, king Milutin’s church at Gračanica, built before 1321, represents the culmination of Late Byzantine architectural design. Integrating a highly attenuated cross-in-square naos with a pi-shaped ambulatory, the whole is topped by five domes. With simplified façade arcading and a pyramidal massing of forms, the building exhibits an external clarity that belies its complexity.

Lesnovo

The reigns of both Milutin and Stefan Dušan witnessed a great deal of construction, often similar to developments in northern Greece. The monastic church at Lesnovo (in modern North Macedonia) built 1341-47, for example, is a grand cross-in-square church with a domed narthex. It would not seem out of place in Late Byzantine Thessalonike in its scale, construction technique, or style.

Ravanica Monastery

Later architecture in Serbia, notably that of the so-called Morava School, is smaller and more decorative, often utilizing the so-called Athonite plan (with choroi and subsidiary chapels), as at Ravanica (1370s), with five domes, or the smaller and simpler Kalenić (after 1407).

Romania

Romania represents a latecomer to the scene. Wallachia (a historical region in southeastern Romania), liberated from Hungary in 1330, came under the influence of Serbian architecture, while Moldavia (a historical region in northeastern Romania), liberated in 1365, shows a greater originality.

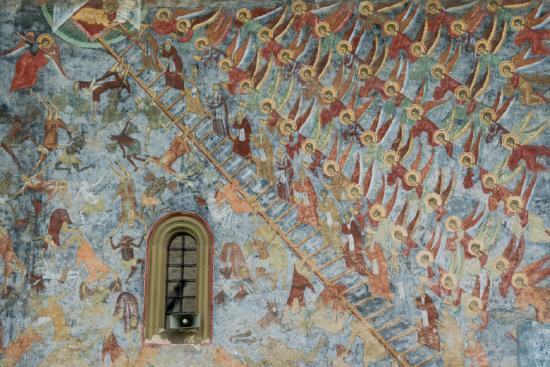

Fifteenth-century churches like that at Voroneţ, built c. 1488, or Suceviţa, built c. 1485, have steeply pitched, heavy overhanging roofs and a diminished dome above a triconch plan, the walls entirely frescoed on the exterior. The origin of this distinctively hybrid architecture is unclear.

Russia

Russia was destabilized in the thirteenth century by the invasion of the Mongols, with the notable exceptions of Novgorod and Pskov, where medieval churches survive from the twelfth century onward.

In Novgorod, churches like the Saviour-on-the-Ilyina-Street (1374), are steep-roofed and roughly built. As Russia recovered from the Mongol invasions, Muscovy developed its own distinctive architecture, first seen perhaps in the Dormition Cathedral in Zvenigorod (c. 1399). Moscow emerged as the most important center, and following the fall of Constantinople in 1453, it assumed the role of spiritual leader of the Orthodox world.

In the late fifteenth century, a new architectural impetus arrived from Italy, in the form of imported Italian architects.

The Cathedral of the Dormition in the Kremlin, constructed 1475-79 under the direction of Aristotele Fioravanti, combined details derived from the Cathedral of Vladimir with an Italian Renaissance modular plan, topped by five domes; it became the coronation church.

Cathedrals of the Annunciation and of the Archangel were added to the Kremlin shortly thereafter.

Anatolia

With the defeat at Manzikirt in 1071, much of Anatolia passed into the control of the Seljuqs and other Turkic beyliks, but this does not mark the end of Christian architecture in the region.

In the thirteenth century, there is evidence of rock-cut architecture in the Christian communities of Cappadocia (in central Anatolia), as for example at Tatlarin, Gülşehir, and Belisırma.

By the early fourteenth century, the Ottomans emerged as the dominant power in northwest Anatolia, and by the 1320s–1330s, the former nomads were actively building, and in a manner technically and stylistically following local, Byzantine practices, although plans and vaulting forms may be more closely aligned with the architecture of the Seljuqs.

The Orhan Mosque in Bursa of the late 1330s corresponds closely to contemporaneous works of Byzantine architecture in its mixed brick and stone wall construction and its decorative details.

Many of the same features appear at the church of the Pantobasilissa in nearby Trilye, also from the late 1330s, suggesting that the same workshops were constructing both churches and mosques. At Bursa, the first Ottoman capital (conquered in 1326), two Byzantine churches were appropriated for use as the mausolea of Osman and Orhan.

Monasteries

Monasticism follows Middle Byzantine models, as for example at Hilandar on Mount Athos, founded by Milutin c. 1303.

The freestanding, Athonite-plan katholikon included a large, twin-domed narthex or lite, subsequently expanded with a large, domed outer narthex in the latter part of the century. Both reflect the increased role of the narthex in monastic worship.

Fortified, with the monastic cells lining the wall, the monastery has its refectory set opposite the entrance to the katholikon, with a phiale or holy water font in the courtyard to one side. Similarly planned monasteries appear throughout the Balkans.

Byzantine miniature mosaics

by Dr. Evan Freeman

For many of us, the term “mosaics” evokes the soaring golden walls and ceilings of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire. But from approximately the twelfth to the fourteenth century, the Byzantines also began creating mosaics that were portable and sometimes small enough to fit in the palm of the hand.

Historians often speak of the Late Byzantine period (1261–1453) as an age of “decline.” During this time, the Byzantine Empire—which was a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire—shrank until it was finally conquered by the Ottomans in 1453. But Byzantine miniature mosaics, which emerged as a new art form in the twilight of the Empire, show that even as Byzantium’s imperial prospects faltered, artistic creativity and patronage continued to flourish.

Mosaics

A mosaic is an artwork made by combining small cubes (tesserae) of stone, glass, ceramic, or another material to create a pattern or image. The ancient Romans often used mosaics to decorate floors, as seen at the Baths of Neptune in Ostia. In some cases, ancient Roman mosaics utilized small, colored tesserae that enabled them to appear almost like paintings.

Later, the Byzantines frequently used mosaics to decorate the walls and ceilings of churches. Mosaics were the costliest form of monumental decoration in Byzantium, and were generally favored by imperial and other elite donors, as seen, for example, in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna and in Hagia Sophia, the cathedral in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, modern Istanbul (see Figure \(\PageIndex{54}\)).

Miniature mosaics

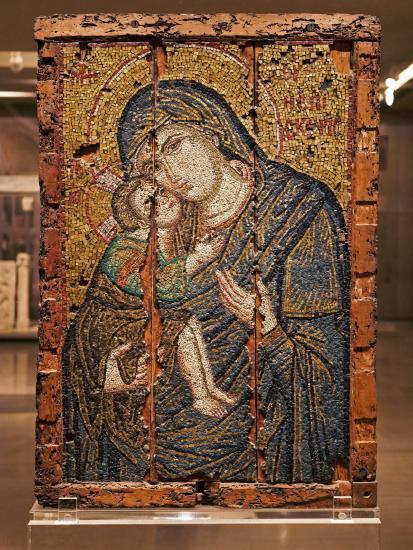

From around the twelfth century to the fourteenth century, the Byzantines also began creating portable mosaic icons by setting small tesserae into wax or resin on wood panels, which were often enclosed in silver-gilt frames. These objects are sometimes referred to as “miniature mosaics” or “micro-mosaics.” While the Byzantines had long used mosaics for large scale images in buildings, this new use of mosaics to create smaller, portable images was innovative.

Since monumental mosaics were generally viewed from afar, individual tesserae tended to blend together in the vision of the beholder. But since miniature mosaics could be viewed up close, artists began employing tiny tesserae—often as small as 0.5–1 mm, or even smaller—to create a blended rather than a “pixilated” appearance. Such objects must have demanded considerable time and skill to create.

There is little evidence to indicate where or why miniature mosaic icons began to be produced when they did. Some scholars theorize that miniature mosaics may have initially emerged as a preparatory step in the production of monumental mosaics, which enabled artists to plan ahead what they would put on walls or ceilings. Because of the cost and skill that must have been required to produce them, miniature mosaic icons were likely created for imperial and other elite patrons by artists who produced luxury objects in Constantinople. Some fifty miniature mosaic icons survive—most of them from the Late Byzantine period—although many are badly damaged. Byzantine inventories suggest that more once existed, which have not survived.

Larger mosaic icons, such as the thirteenth-century icon of the Virgin Glykophilousa in Athens, sometimes measured several feet tall (see Figure \(\PageIndex{55}\)). Their size suggests they may have been publicly displayed and venerated in churches. Some may have been installed on the templon barrier that divided the altar area from the rest of the church. Other mosaic icons, such as the early fourteenth-century icon of the Virgin Eleousa in New York, were small enough to be held in the palm of one hand (see Figure \(\PageIndex{}\)). They would have been too small for public display and were likely used in private devotion.

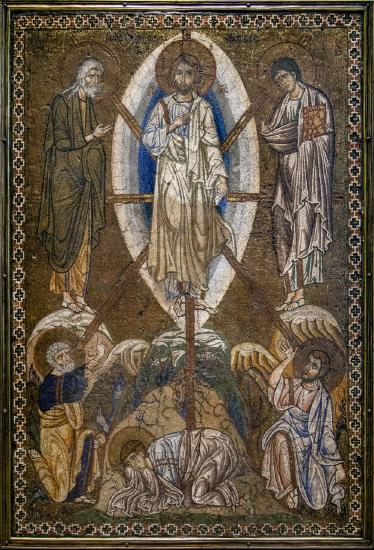

An Icon of Christ’s Transfiguration

A mosaic icon of Christ’s Transfiguration in the collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris offers an early example of the miniature mosaic technique, dating from c. 1200. Its miniature tesserae—made from gilded bronze, marble, lapis lazuli, and glass—measure between 0.5 mm and 1 mm on a side (about the diameter of a pencil lead; see Figures \(\PageIndex{57}\) and \(\PageIndex{59}\)). Its owner(s) undoubtedly treasured this icon not only for its beauty and religious significance, but also as an object of great luxury. Based on its size, this icon may have been displayed in a church or used for private devotion.

The icon depicts the Transfiguration as described in the New Testament—in Matthew 17:1–13, Mark 9:2–8, and Luke 9:28–36—when Christ reveals his divinity to three of his apostles, Peter, James, and John. Christ and his apostles climb a mountain (identified by tradition as Mount Tabor). Suddenly, Christ is transformed, radiating brilliant, heavenly light. Moses and Elijah, prophets from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians refer to as the Old testament), appear on either side of Christ, and the voice of God from heaven identifies Jesus as his Son. The apostles fall down before Christ in fear. The white tesserae used to create Christ’s garments and the mandorla of light that surrounds him, as well as the reflective, gilded tesserae used for the rays and background, must have helped evoke the divine light for Byzantine viewers. The composition closely corresponds with some of the earliest surviving images of the Transfiguration, such as the sixth-century mosaic in the apse of the basilica of the Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai, Egypt (see Figure \(\PageIndex{58}\)).

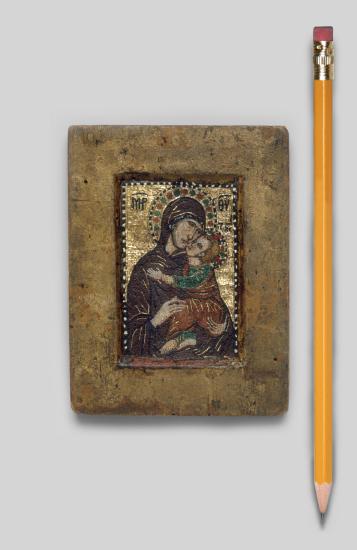

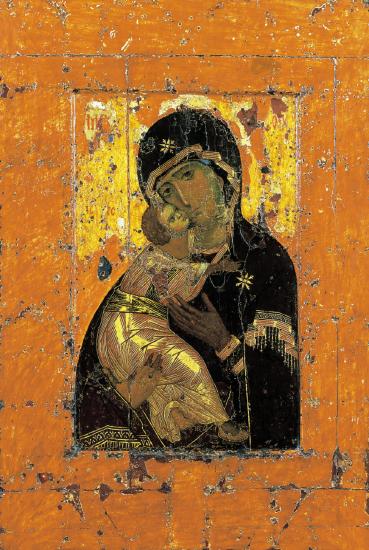

An Icon of the Virgin Eleousa

Another miniature mosaic icon (see Figure \(\PageIndex{60}\)) depicts the Virgin and Child rather than a narrative scene and is part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Created in the early 1300s, roughly a century after the Louvre’s Transfiguration icon, the Met’s miniature mosaic shows the Virgin Eleousa (“compassionate”), who tenderly holds the Christ child to her cheek. The Virgin Eleousa was one of many compositions of the Virgin and Child in Byzantium; its best-known example is probably the Virgin of Vladimir, which was transferred from Byzantium to Russia in the twelfth century, where it became well-known and widely imitated.

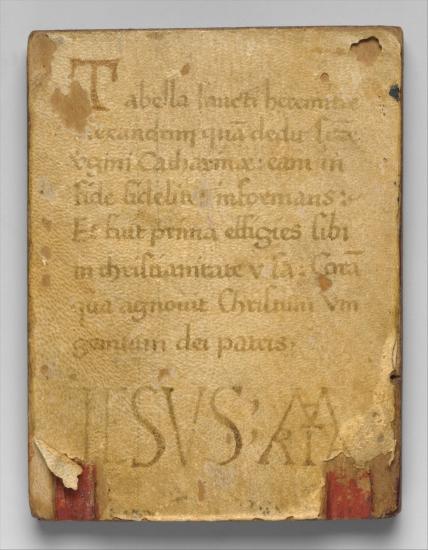

The miniature mosaic icon of the Virgin and Child at the Metropolitan is smaller than the Louvre’s Transfiguration, measuring 11.2 x 8.6 cm, and likely functioned as a private devotional object. A fifteenth-century Latin inscription on the icon’s back testifies to its preservation in western Europe following the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 (see Figure \(\PageIndex{61}\)).

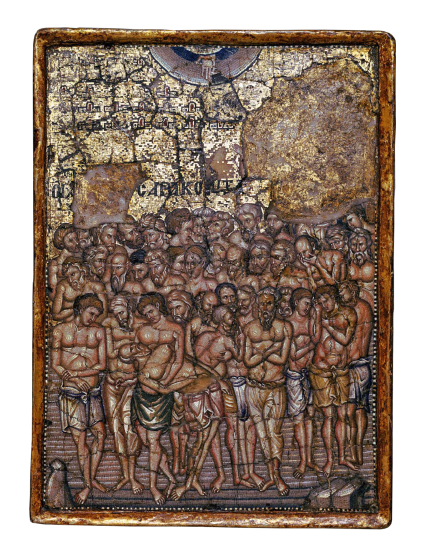

An Icon of the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia

Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. preserves another fine example of Byzantine miniature mosaics, this time picturing an account of Christian martyrdom: the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia (see Figure \(\PageIndex{62}\)). The icon dates to the late thirteenth century, combines gold and multicolored stone tesserae set in wax on a wood panel, and has been somewhat damaged. The icon utilizes tiny tesserae measuring less than 0.5 mm, which must have made the production of this icon long and difficult, but which gives the image an almost painterly appearance.

The image recounts the tale of forty Roman soldiers sentenced to die for their Christian faith by exposure in a frozen lake in Lesser Armenia around 320 CE. The artist has taken no shortcuts, rendering the figures in individual poses that convey their suffering. One man in the foreground collapses. Another, in the upper right, holds his hands to his face in distress. The soldiers’ suffering is vindicated as the hand of God bestows crowns of martyrdom on the soldiers from a heavenly dome in the top of the mosaic.

Such miniature mosaic icons illustrate how the arts flourished in the final centuries of the Byzantine Empire. Although the medium of mosaics had been used to decorate buildings since ancient times, artists from the twelfth-century onward reimagined the medium to create small, portable icons that were nothing short of innovative.

Picturing salvation: Chora’s brilliant Byzantine mosaics and frescoes

by Dr. Evan Freeman

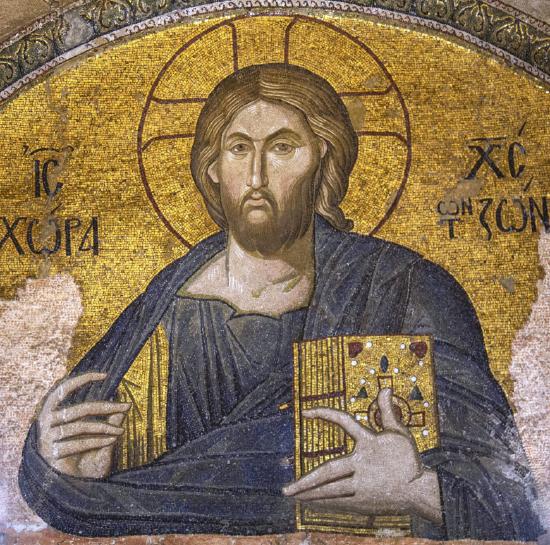

An arresting, larger-than-life mosaic of Christ confronts viewers entering the Chora, a church that was once part of a monastery in the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul). The bust-length Christ, who blesses viewers with his right hand and holds a jeweled Gospel book in his left hand, appears in the lunette above the door between the outer and inner narthex (view location in plan). Such depictions of Christ are commonly known as the “Pantokrator,” which means “almighty.” This mosaic is one of many well-preserved mosaics and frescoes in this church, which date to the fourteenth century.

Power and patronage

These mosaics and frescoes are the result of patronage by a wealthy intellectual and high-ranking official named Theodore Metochites, who restored the Chora c. 1316–1321, where he intended to be buried when he died. The early history of the Chora monastery is hazy, but the core of the current church was built in the twelfth century by Isaac Komnenos and fell into disrepair when Constantinople was sacked by western Europeans in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade.

About a century later, Metochites, a scholar of classical texts who donated his personal library to the Chora, held the position of Mesazon, or “prime minister,” to emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos, making him the second most powerful man in the empire. As ktetor (“founder,” or in this case, re-founder) of the Chora, Metochites oversaw the restoration of the twelfth-century church as well as the addition of inner and outer narthexes and a subsidiary chapel, or parekklesion, which served as a funeral chapel. The Chora’s rich mosaics and frescoes—among the finest examples of Late Byzantine art—illustrate Theodore Metochites’ ambition and his hope for salvation after death.

Jesus Christ, land of the living

Despite his seemingly stern gaze, the entrance mosaic of Christ Pantokrator is optimistically labeled “Jesus Christ, the land (chora) of the living,” a play on the monastery’s name, which likely originally referred to its location “in the country” outside of the city walls built by emperor Constantine. This phrase—“land of the living”—comes from Psalm 116:9: “I walk before the Lord in the land (chora) of the living.” [1] The same text from Psalm 116:9 also appears in the Orthodox funeral service, which would have taken place in the Chora’s funeral chapel. So, by labeling Christ “land of the living,” Metochites put a spiritual spin on the Monastery’s name while also expressing hope for eternal life within the church where he planned to be buried.

Mother of God, container of the uncontainable

This mosaic of Christ faces a mosaic on the opposite wall, which pictures the Virgin with hands raised in prayer and the Christ child over her torso as if in her womb (view location in plan). The Virgin is labeled: “Mother of God, container (chora) of the uncontainable (achoritou).” This phrase, which describes the paradox that a human (Mary) could contain the Son of God (Jesus) in her womb, similarly references the monastery’s name. Such prominent images of Christ and the Virgin in the Chora reflect their important role in the Christian story of salvation, as well as the fact that the Chora monastery and parekklesion were likely dedicated to the Virgin and the main church to Christ.

Donor image

Proceeding into the inner narthex, viewers encounter a mosaic of the patron himself, Theodore Metochites, in the lunette over the door to the main part of the church, or naos (view location in plan; see Figure \(\PageIndex{69}\)). Christ sits on a jeweled throne against an expansive gold ground. Metochites kneels to Christ’s right, dressed in extravagant garments and wearing a flamboyant, turban-like hat, the asymmetry of the composition emphasizing the interaction between the two figures. This mosaic suggests Theodore’s high position within the empire but also his submission to Christ. As was common in medieval donation scenes, Metochites offers a model of the Chora—the very church in which this mosaic is located—to Christ.

Deësis

To the right, on the eastern wall of the inner narthex, a monumental Deësis mosaic shows the Virgin asking Christ to have mercy on the world (view location in plan; see Figure \(\PageIndex{70}\)). Because of her important role as the Mother of God, the Byzantines viewed the Virgin as a powerful intercessor between Christ and the faithful. John the Baptist, often included in the Deësis, has been omitted, probably to maximize the scale of the image within the space. Two past patrons of the Chora kneel on either side: Isaac Komnenos and a nun labeled “Melanie, the Lady of the Mongols,” who may be the daughter of emperor Michael VIII.

The Chora and Hagia Sophia

For Byzantine viewers, the image of Theodore Metochites would have called to mind two imperial images in Constantinople’s great cathedral, Hagia Sophia. Metochites’ gesture of donation evokes the tenth-century mosaic of Constantine and Justinian offering models of the city and Hagia Sophia to the Virgin and Child in the southwest vestibule. And Metochites’ kneeling gesture and position above the central door to the naos echoes the tenth-century mosaic of the prostrating emperor above Hagia Sophia’s “Imperial Door.”

The large scale of the Chora’s Deësis alludes to the monumental Deësis mosaic installed in Hagia Sophia’s south gallery—a section of the church reserved for imperial use—following the Latin crusaders’ occupation of Constantinople from 1204–1261. These visual echoes, or “intervisuality” between the Chora and Hagia Sophia, suggest Metochites’ desire to associate himself with Byzantium’s emperors, and his church with the capital’s cathedral, Hagia Sophia. [2]

Christ and the Virgin

Christ and the Virgin are the main subjects of the majority of the mosaics that fill the inner and outer narthexes. Narrative scenes from the lives of the Virgin and Christ adorn various architectural spaces, and often exhibit experimentation with figures and compositions.

In a dynamic depiction of the Annunciation, the Virgin looks awkwardly over her shoulder as Gabriel approaches from above. The image responds to the triangular architectural surface in which it is situated, resulting in an unconventional, diagonal composition.

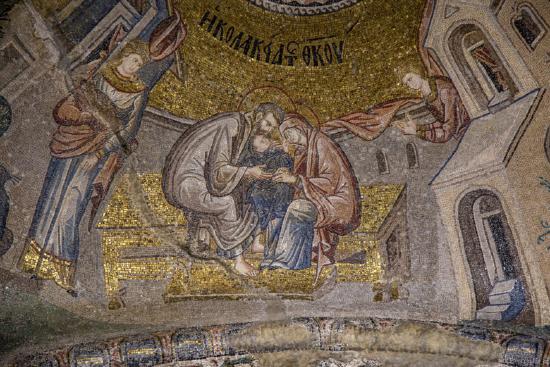

An image of the Virgin Mary with her parents exhibits a remarkable intimacy and evokes everyday life. Such “everyday” images in the Chora challenge common generalizations about Byzantine art as distant, spiritualized, and otherworldly.

The mosaics of the inner narthex culminate with two pumpkin domes (named for their fluted shape that resembles the undulating surface of a pumpkin) that display mosaics of Christ and the Virgin surrounded by their saintly ancestors from scripture (view location in plan).

Within the Chora, all human history seems to point toward these two figures and the pivotal role they play in the salvation of humankind.

The main church

Only three mosaics survive in the main church today. A mosaic of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary appears on the back western wall of the naos (see Figure \(\PageIndex{77}\)). And pair of proskynetaria icons of Christ and the Virgin once flanked the templon (the barrier between the sanctuary and naos, which no longer survives). These three images indicate that the emphasis on Christ and the Virgin that began in the narthexes continued in the main church where the Eucharist was celebrated.

The Parekklesion

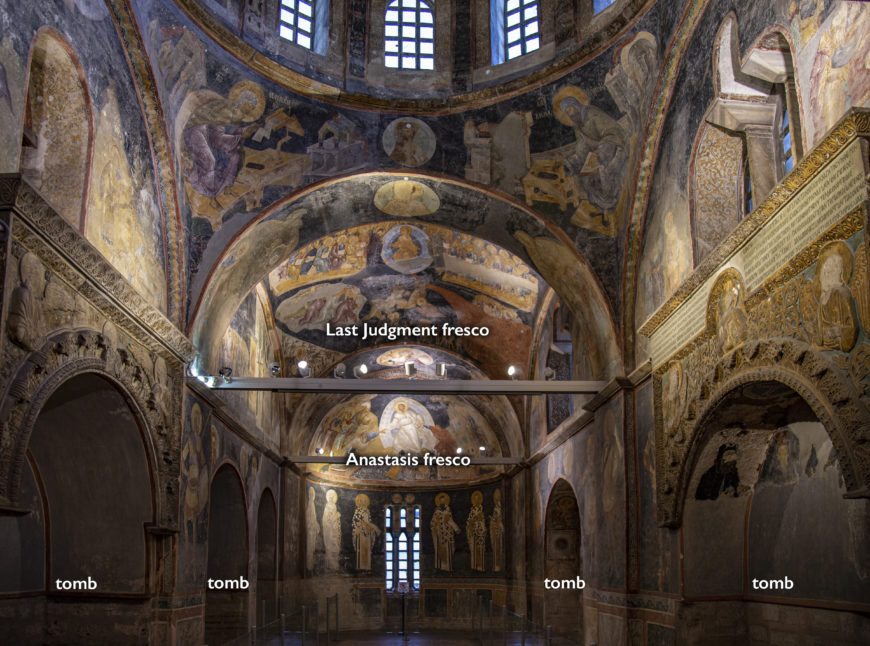

Better preserved are the frescoes in the parekklesion (side chapel), located to the south of the main church, which present a message of salvation that is fitting for this funeral chapel. Arcosolia (arched recesses for tombs) punctuate the walls and were intended for the burial of Metochites and his loved ones (view location of tombs in plan; see Figure \(\PageIndex{81}\)).

One enters the parekklesion beneath a dome decorated with frescoes of the Virgin and Child surrounded by angels (view location in plan). Hymnographers appear in the pendentives beneath the dome. Further below are scenes from the Old Testament, including Jacob’s ladder, Jacob wrestling the angel, Moses and the burning bush, scenes with the Ark of the Covenant, and more, which were understood as “types” of Christ and the Virgin. In other words, the Byzantines believed these episodes from the Old Testament prefigured Christ’s salvation of humankind. At ground level, soldier saints surround the tombs, brandishing their weapons like sacred guardians over the dead.

Judgment and Resurrection

Proceeding further into the parekklesion, the viewer passes under a sprawling image of the Last Judgment, sobering but also hopeful, since it depicts the damnation but also the salvation of souls (view location in plan; see Figure \(\PageIndex{382\)). The parekklesion frescoes culminate at the east end with images of resurrection, reflecting the Christian belief that God will raise the dead at the end of time.

The focal point of the parekklesion is the Anastasis (“resurrection”) fresco in the apse (view location in plan; see Figure \(\PageIndex{85}\)). The voluminous garments on the figures in this scene are a hallmark of Late Byzantine art. Drawn from non-biblical texts, the Anastasis visualizes Christ descending into Hades (the underworld) following his crucifixion to free human souls from the captivity of death. Christ’s death on the cross has paradoxically made him a victor over death, as described in the Orthodox hymn for Pascha (Easter): “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life!” Clad entirely in white, Christ strides dynamically over the broken locks and doors of the underworld, and a personification of Hades lies bound and defeated at the bottom of the composition. Adam and Eve—the archetypal first humans responsible for bringing sin and death into the world—are forcefully pulled from their tombs by the risen Christ.

Hope for salvation

Despite his considerable learning and political ambition, Metochites remained mindful of his mortality as he rebuilt the Chora monastery. While his donor image clearly communicated his position and achievements to all who entered the church, the frescoes of the parekklesion speak to Metochites’ anticipation of God’s judgment and his hope for resurrection and eternal life in the chora, or land, of the living.

Notes

[1] The Byzantines used a Greek version of the Hebrew Bible known as the Septuagint. This passage appears in the Septuagint Psalm 114:9.

[2] Robert S. Nelson, “The Chora and the Great Church: Intervisuality in Fourteenth-Century Constantinople,” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 23 (1999): 67–101.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout, "Late Byzantine church architecture," in Smarthistory, September 18, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Evan Freeman, "Byzantine miniature mosaics," in Smarthistory, January 25, 2021 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Evan Freeman, "Picturing salvation — Chora’s brilliant Byzantine mosaics and frescoes," in Smarthistory, April 28, 2021 (CC BY-NC-SA)