15.5: Christian East Africa

- Page ID

- 108702

Christian Ethiopian art

by Dr. Jacopo Gnisci

Ethiopia is a country in Africa with ancient Christian roots. It possesses a vigorous artistic tradition and is home to hundreds of old churches and monasteries perched at the top of hard-to-access mountains, hidden by lush vegetation, or surrounded by the tranquil waters of one of its lakes.

What is Christian Ethiopian art?

The introduction of Christian elements in art and the construction of churches in Ethiopia must have started shortly after the introduction of Christianity and continues to this day, since about half of the population are practicing Christians. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church claims that Christianity reached the country in the 1st century CE (thanks to the conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch described in the Acts of the Apostles 8:26-38), while archaeological evidence suggests that Christianity spread after the conversion of the Ethiopian king Ezana during the first half of the 4th century CE.

The term “Christian Ethiopian art” therefore refers to a body of material evidence produced over a long period of time. It is a broad definition of spaces and artworks with an Orthodox Christian character that encompasses churches and their decorations as well as illuminated manuscripts and a range of objects (crosses, chalices, patens, icons, etc.) which were used for the liturgy (public worship), for learning, or which simply expressed the religious beliefs of their owners. We can infer that from the thirteenth century onwards works of art were for the most part produced by members of the Ethiopian clergy.

Periodization

Artworks from Ethiopia can and should be contextualized within the country’s historical development. Scholars still disagree on how to divide and classify the development of Christian Ethiopian art into chronological phases. In this essay, the development of Christian Ethiopian art is broadly divided into the eight periods listed below, but it must be kept in mind that the dates for the earlier periods are still debated and we have very limited evidence prior to the early Solomonic period (1270-1527).

The Christian Aksumite Period (c. 4th-8th centuries CE)

This period takes its name from the city of Aksum which had been the capital of Ethiopia for several centuries before the conversion to Christianity of King Ezana (who ruled from c. 320–360) and served as capital for several centuries after. While we cannot rule out the possibility that Christianity had been present in the country prior to the conversion of this ruler, it is only starting from this period that expressions of distinctly Christian beliefs appear in the material record.

A small number of Ethiopian churches, such as Debre Damo (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) and Degum, can be tentatively ascribed to the Aksumite period. These two structures probably date to the 6th century or later. Still standing pre-6th century Aksumite churches have not been confidently identified. However, archaeologists believe that a small number of now-ruined structures dating to the 4th or 5th century functioned as churches—a conclusion based on features such as their orientation. A large stepped podium in the compound of the church of Mary of Zion in Aksum (considered by the Ethiopians as the dwelling place of the Ark of the Covenant), probably once gave access to a large church built during this period.

Aksumite churches adopted the basilica plan. These churches were constructed using well-established local building techniques and their style reflects local traditions. Although very little art survives from the Aksumite period, recent radiocarbon analyses of two illuminated Ethiopic manuscripts known as the Garima Gospels suggest that these were produced respectively between the 4th-6th and 5th-7th centuries. Aksumite coins can also be looked at to gain insight into artistic conventions of the period (see Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

The Post-Askumite period (c. 8th/9th-12th centuries CE)

A number of factors contributed to the gradual impoverishment and decline of the Aksumite kingdom. The Arab expansion into Northern Africa cut off the kingdom’s access to the Red-Sea waterway (and to the markets which could be reached through it and on which a large part of the kingdom’s prosperity had been based). There is also evidence to suggest that some of the kingdom’s natural resources, such as gold and ivory, had been depleted. Very little is known about this phase of Ethiopian history and scholars even disagree on the dates of its beginning and end.

The political center of Ethiopia seems to have gradually shifted to the southern and eastern parts of the Tigray region in the Post-Aksumite period. A few churches in these areas have been tentatively attributed to this period, but subsequent adaptations combined with the inability to obtain permissions to conduct archaeological surveys make dating difficult. It seems likely that churches continued to be built as well as hewn (cut) out of rock. A group of funerary hypogea, or underground chambers, in the Hawzien plain (in northern Ethiopia) may have been transformed into churches during the post-Aksumite period. This could be the case for churches such as Abreha-we-Atsbeha (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)) and Tcherqos Wukro (the paintings in these churches probably date from a later period). According to local oral traditions, a small number of iron crosses date to the Aksumite or Post-Aksumite periods, but the absence of reliable dating methods and the fact that such crosses were produced at least until the sixteenth century, makes it extremely difficult to verify these claims.

The Zagwe period (c. 1140-1270 CE)

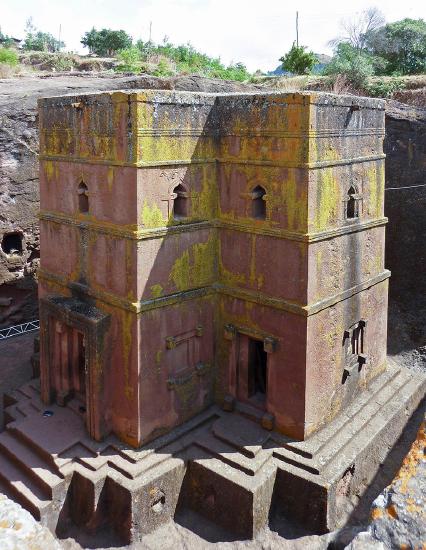

By the first half of the twelfth century, the center of power of the Christian Kingdom had shifted even further south, to the Lasta region (a historic district in north-central Ethiopia). From their capital Adeffa, members of the Zagwe dynasty (from whom this period takes its name), ruled over a realm which stretched from much of modern Eritrea to northern and central Ethiopia. While limited evidence about their capital exists, the churches of Lalibela—a town which takes its name from the Zagwe ruler credited with its founding—stand as a testament to the artistic achievements of this period (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Lalibela includes twelve buildings destined for worship which, together with a network of linking corridors and chambers, are entirely carved or “hewn” out of living rock (see Figures \(\PageIndex{1}\) and \(\PageIndex{7}\)). The tradition of hewing churches out of rock, already attested in the previous periods, is here taken to a whole new level. The churches, several of which are free-standing, such as Bete Gyorgis (Church of St. George, image at top of page), have more elaborate and well-defined façades. They include architectural elements inspired by buildings from the Aksumite Period. Furthermore, some, such as Bete Maryam, feature exquisite internal decorations (see Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)), which are also carved out of the rock, as well as wall paintings. The interiors of the churches blend Aksumite elements with more recent elements of Copto-Arabic derivation. In Bete Maryam, for example, the architectural elements—such as the hewn capitals and window frames—imitate Aksumite models (see Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)), whereas the paintings can be compared with those in the medieval Monastery of St. Antony at the Red Sea.

Several wooden altars survive from this period, some decorated with figures, together with numerous crosses, some of which are engraved. No illuminated manuscripts or icons from this period have been discovered thus far.

The Early Solomonic period (1270-1527)

By 1270, the last Zagwe ruler was overthrown by Yekunno Amlak, who claimed to descend from the kings of the Aksumite period and traced his lineage all the way back to the biblical union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. His descendants—the Solomonics—ruled Ethiopia until the third quarter of the twentieth century. For much of this period, the Solomonics did not have a fixed capital, but moved across the country according to the seasons and their needs.

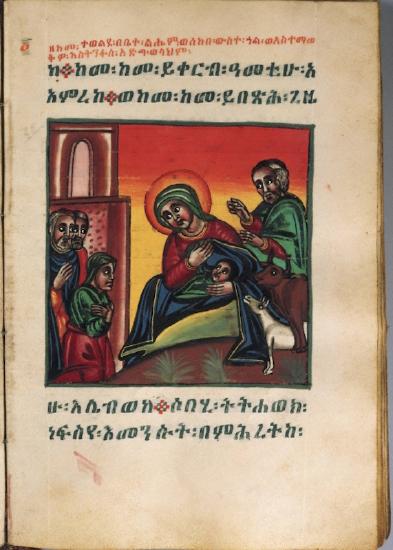

The Solomonics were as active as patrons of the arts as their predecessors, and endowed churches with hundreds of precious gifts. Works of art were also donated to ecclesiastic centers by nobles and clergymen, as well as by individuals known from dedicatory inscriptions on the work they commissioned. The rock-cut church of Gannata Maryam, a few kilometers south-east of Lalibela, features an almost complete set of murals depicting saints, angels, and motifs inspired by the New Testament. The church also features a portrait of Yekunno Amlak. Numerous illuminated manuscripts, particularly Gospel books, were created between the late thirteenth and early fifteenth centuries. A few dozen feature not just Canon Tables and portraits of the four Evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John), as in the earlier Garima Gospels, but also scenes from the Old and New Testaments.

By the turn of the fifteenth century other manuscripts, especially Psalters, are frequently illustrated and crosses are often embellished with depictions of saints and of the Virgin and Child (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). The earliest surviving Ethiopian icons also date from this century (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)) and Diptych with Mary and Her Son, discussed in the next section). Written sources suggest that the Ethiopian Emperor Zar’a Ya’eqob encouraged the use of panel paintings in church rituals. While other artistic mediums used during the fifteenth century are largely indebted to the art of the fourteenth century, the icons feature new iconographic motifs and the lines are more elegant and sinuous and the figures have less rigid poses.

The mid-Solomonic period (1527-1632)

After a period of relative stability in the fifteenth century, a sequence of events shook the Ethiopian kingdom to its foundations, bringing it to the brink of collapse. First, came an invasion from the neighboring Muslim Sultanate of Adal led by a general called Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi whose army pillaged and destroyed numerous churches and Christian works of art across the country between 1529 and 1543. Incursions by the Oromo people from the south throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries further strained the country’s fragile structures. To make matters worse, the conversion to Catholicism of Emperor Susenyos in 1622 soon plunged the country into a civil war, for many of his subjects refused to adhere to the religious beliefs and liturgical practices that the Jesuit missionaries present in Ethiopia wanted to enforce. The conflict lasted until his abdication in favor of his son Fasilides in 1632.

This phase of Ethiopian art has been sometimes described as period of “transition” because artworks produced during the sixteenth century still include stylistic and iconographic elements that are typical of the fifteenth century, while foreshadowing developments which will take place in the second half of the seventeenth century. However, as such, this description of transition is applicable to most historical periods, and is therefore not particularly helpful. The art produced during the mid-Solomonic period reflects the difficult situation the country was in (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). The practice of decorating manuscripts with pictures and geometric motifs declined considerably, and few crosses and churches have been confidently attributed to the sixteenth century. Moreover, although numerous icons from this period have survived, these seldom achieve the linear elegance of painted panels from the fifteenth-century.

The Gondarine period (1632-1769)

The ascent to the throne of Fasilides in 1632 marks the beginning of a period of renewed stability for Ethiopia and the Solomonic dynasty. Fasilides ordered a new a capital, Gondar, about 50 kilometers north of Lake Tana (the largest lake in Ethiopia). He and his successors funded the construction of palaces and banquet halls within the royal compound that still exist today and they promoted the building of churches near by and in the Lake Tana region. The adoption of a circular plan for the construction of churches becomes standard, as opposed to the longitudinal format of the basilica.

Scholars usually divide the Gondarine period into two stylistic phases. The first Gondarine style, is characterized by the use of bright colors and the absence of shading (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). The clothing, often embellished with decorative elements, is usually painted in red, blue or yellow and the folds are indicating with simple parallel lines. The contour lines are well-defined and the modeling of the face is executed using a plain coral red resulting in an unnatural effect.

Works painted in the second Gondarine style (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)), which was developed roughly during the reign of Iyasu II (1730-1755), have darker shades of color; the contour lines become lighter and a more delicate use of shading confers volume to the bodies and faces of the figures. A number of new themes, many of which were inspired from books printed in Europe, appear during the eighteenth century and it becomes increasingly common to find depictions of donors and patrons. Numerous crosses (like this processional cross from The British Museum), decorated with depictions of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and saints were produced during the second part of the Gondarine period.

Zemene Mesafint period (1769-1855)

The period known as Zemene Mesafint, or the Era of Judges, begins with the deposition of Emperor Iyosas. This period, which lasted almost a century, saw a decline in the prestige, influence, and authority of the Solomonics, and witnessed the rise of a number of regional warlords who fought against each other for supremacy. This period has received less attention from historians, but seems to have been characterized by a decline in the production of art. Paintings from this period are strongly indebted to works executed during the second Gondarine style in terms of themes and forms, but the palette used by artists moves once again toward bright, plain colors.

The Late Solomonic period (1855-1974)

The final historical period begins with the ascent to the throne of Tewodros II, who claimed Solomonic descent and ends with the deposition of Haile Selassie, the event that marks the end of Solomonic rule in Ethiopia.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, church painting continues to show indebtedness to the second Gondarine style, but contemporary figures and events are depicted next to religious subjects with an increasing frequency. Moreover, while patrons had occasionally been depicted from the Zagwe period onwards in an idealized manner, by the turn of the twentieth century they are portrayed more realistically, as can be seen by the painting of Emperor Menelik II (see Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)) in the church of Entoto Raguel. After the Second World War, traditionally trained Ethiopian painters, such as Qes Adamu Tesfaw, continued to work alongside artists influenced by modernism. The use of imported synthetic colors became increasingly common and by the 1960s icons and manuscripts were created, to a large extent, for the tourist market.

An Ethiopian icon

by Dr. Jacopo Gnisci

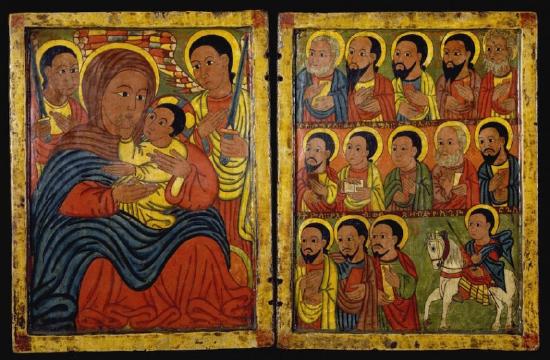

The term icon is used to refer to a devotional image. It is typically painted on a flat wooden panel, although in Ethiopia, as in other traditions, materials such as metal or stone could also be used to produce this type of image. The earliest known Ethiopian icons have been dated to the fifteenth century and are generally painted with tempera on gesso-primed wooden panels. Ethiopian icons from this period typically portray the Virgin and Child, the Apostles, and Saint George.

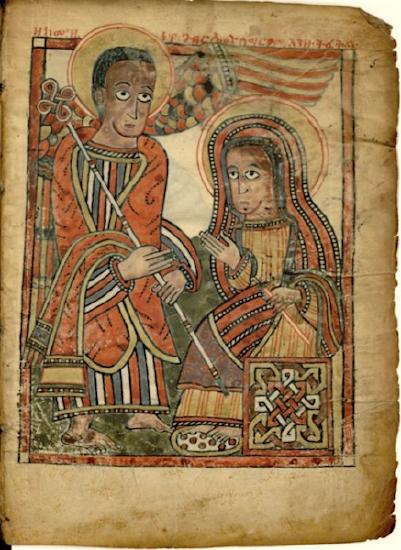

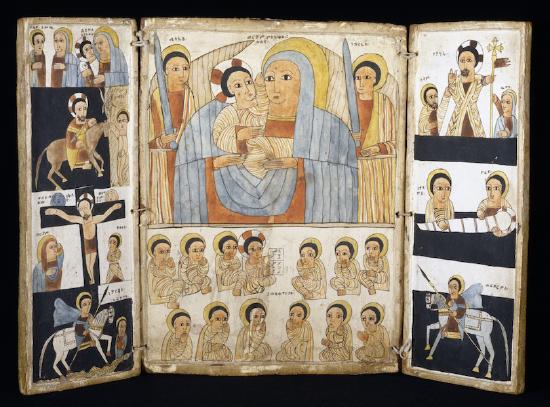

The piece shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\), which can be dated tentatively to the second half of the fifteenth century, features precisely such a combination of subjects. On the left panel, the Child touches his Mother’s chin, a gesture of tenderness which appears more frequently in works from this period onwards. The central pair is flanked by two angels with unsheathed swords who act as their royal guard.

The right panel is decorated with portraits of the Apostles who turn their gaze in adoration towards the Virgin and Child. In the bottom right corner is a representation of Saint George on horseback. The names of several of the figures on the right panel have been written on the borders which divide the scene into registers. It is likely that inscriptions identifying the upper row of Apostles and the Virgin and Child were originally present on the upper frame of the two panels. Icons such as this were most likely created to encourage devotion towards the Virgin Mary in accordance with the wishes of the Ethiopian emperor Zarʾa Yaʿ ǝqob (who ruled from 1434–68) and would have been used in churches and in religious processions.

Images of African Kingship, Real and Imagined

by Dr. Kristen Collins and Dr. Bryan C. Keene

The exhibition Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art examines the figure of the Black king, an artistic invention arrived at by Europeans painting during the 1400s.

Nativity (or crèche) scenes from the Middle Ages to today often include three kings, or magi, bringing gifts to the infant Jesus. Often, these scenes include a Black king, sometimes referred to by the name Balthazar (his two traveling companions are known as Caspar and Melchior).

European Christian tradition often referred to Balthazar as coming from Africa, and maps from the time reveal a combination of fantasy, desire, and lived encounters with Africa and African people.

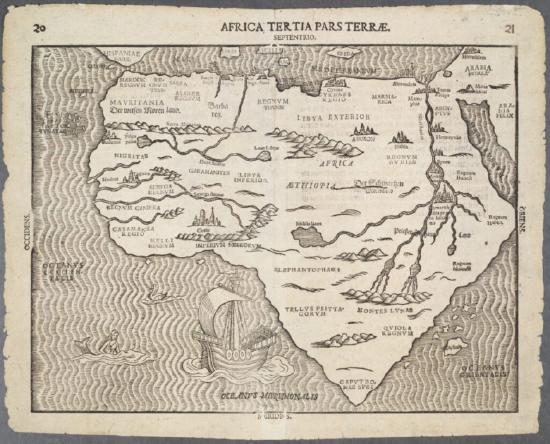

In 1597, German Protestant scholar and cartographer Heinrich Bünting designed a map of Africa marked by both real and imagined kingdoms. In West Africa, we encounter the realm of the Muslim king Mansa Musa of Mali, who was famous for wealth and piety.editerranean North Africa features numerous cultures, including kingdoms in Tunis and Egypt (visible on the map in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)). In East Africa, near the horn of the continent, we read the name of the legendary Christian king Prester John, who was said to reign in Ethiopia or India—reflecting Europeans’ imprecise understanding of world geography at the time. Beginning in the 1440s, Portuguese sailors embarked on searches for Prester John and his mythical kingdom, violently enslaving non-Christian Black Africans along the way.

The mythical Prester John and images of Balthazar reveal European fantasies about Africa and the wealth of kingdoms there. Below we look at three rulers from premodern Africa, each of whom had a major impact on the politics, economy, religion, and culture of the time. We also wish to acknowledge the presence of free Africans living in Europe during this period.

The continent of Africa is vast and was home to more kingdoms than premodern Europeans imagined, and to more than we’re exploring here. While histories of Afro-European contact have traditionally focused on the three faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Africa was home to many other literate and oral religions and traditions.

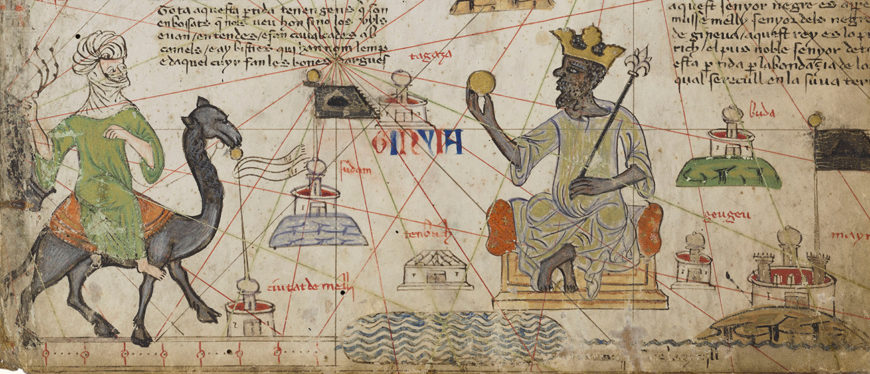

Mansa Musa: The Wealthiest Person in the History of the World

The map of Africa, Europe, and Asia in Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) was created by the Spanish Jewish cartographer Abraham Cresques. It contains a rare medieval depiction of Mansa Musa, who ruled the West African Mali Empire, a territory the covered parts of present-day Mauritania and Mali, from 1312 to 1337. Mansa Musa’s holdings in gold were so great that to this day he is unsurpassed in personal wealth.

A pious Muslim who embraced charitable almsgiving as one of the five pillars of Islam, Mansa Musa made the hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca with an entourage reportedly consisting of 60,000 subjects, 80 camels, and thousands of pounds of gold dust. His donations to the poor and diplomatic gifts along the way pumped so much gold into the economy of the Mediterranean that it devalued gold currency in the wealthy European mercantile cities such as Florence for decades.

The 14th-century Arab scholar Ibn Fadl Allah al-Umari lived in Cairo at the time and later reported on the ruler in his encyclopedia: “This man flooded Cairo with his gifts. He left no court emir nor holder of a royal office without the gift of a load of gold. The people here profited greatly from him and from his entourage in buying, selling, giving, and taking. They traded gold until these lessened its value in Egypt, making its price fall…”

Sultan Qaitbay: Mediterranean Diplomacy with Muslim African Rulers

Italian artists from Florence to Venice traveled frequently throughout the Mediterranean to broker political, religious, and mercantile partnerships with their Muslim neighbors. One powerful individual in the 1400s was the Mamluk sultan of Egypt called Qaitbay, who reigned from 1468 to 1496.

An anonymous Venetian painter depicted a reception scene in Damascus, Syria, between Europeans and representatives of the sultan, whose escutcheon is emblazoned on the gates of the city in the painting (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)). “Glory to our Sultan, the master, the king of kings, the wise, the ruler, the just al-Ashraf Abu al-Nasr Qaitbay, the Sultan of Islam,” reads the gilded inscription, proclaiming the sovereignty of Qaitbay. His dominions stretched from the Nile basin of the southeastern Mediterranean to Israel, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

Like Mansa Musa, Qaitay made a pilgrimage to Mecca and as an act of piety, he commissioned brass candlesticks for the shrine of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina. Architectural monuments built under his reign are still major destinations for curious travelers and the faithful alike.

Qaitbay’s diplomatic relationships included the wealthy Medici merchants in Florence, who received rare and valuable gifts from the Sultan. The most notorious gift that the sultan sent to the Tuscan city-state was a giraffe, which was memorialized in works of art, including a fresco of The Adoration of the Magi by Ghirlandaio in the church of Santa Maria Novella. The arrival of the giraffe with a retinue of Egyptian delegates may have evoked the pageantry of gift-giving reenacted in the annual magi processions in Florence, commemorated each January 6 on epiphany day.

For Qaitbay, such relationships with the Italian courts could lead to financial and military support against their shared rival in the northeastern Mediterranean: the Ottoman Turks. European princes and popes also feared Ottoman expansion and thus maintained ties with the Mamluks. Trade goods from Egypt—including metalwork, manuscripts (from Coptic Christian and Muslim communities), and glassware—had a great impact on European art at the time.

Zar’a Ya’eqob and the Medieval Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia

Ethiopia has a long history as a powerful Christian kingdom, as an empire, and later, as a nation. By the end of the third century, the four great powers of the ancient world were considered to be Rome, Persia, China, and the African kingdom of Axum—which occupied parts of present-day Eritrea and northern Ethiopia.

The later kingdom of Ethiopia, an early adopter of Christianity, developed a vibrant artistic tradition that included rock-hewn churches (such as Lalibela, Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\)), illuminated manuscripts, and liturgical crosses (Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\)). In the 15th century, successive Ethiopian nägäst (rulers) sent church delegations to Italy in an attempt to forge alliances, both religious and military, with Rome.

The 15th-century Ethiopian emperor Zar’a Ya’eqob was known for his strength and diplomacy. Zar’a Ya’eqob, who reigned from 1434 to 1468, resolved a major internal theological strife, a debate over the observance of the Sabbath (holy day of worship) that had been waged for over a century prior to his rule. It was also during his reign that the 1441 delegation joined the Council of Florence, one of the great church gatherings of that century. In Florence, his subjects were perplexed at Europeans’ continued identification of Zar’a Ya’eqob with the legendary priest-king Prester John.

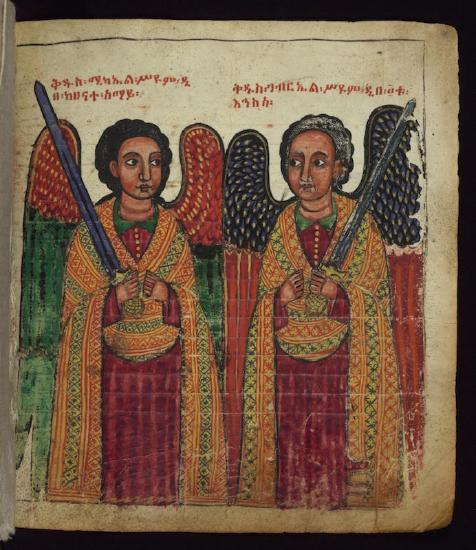

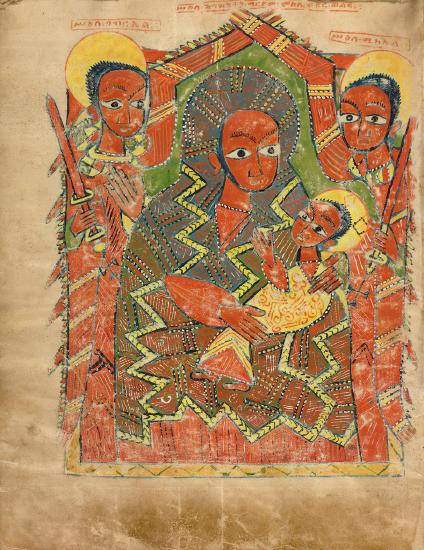

At home, Zar’a Ya’eqob reportedly had an honor guard that stood to either side of his throne, holding drawn swords. The opening image of a Gospel book made at the Gunda Gunde monastery shows the Virgin Mary and Christ child similarly flanked by the archangels Michael and Gabriel (see Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)). The Ethiopian kingdom had been Christian since the fourth century, but Zar’a Ya’eqob had Muslim subjects as well. The emperor’s wife, Eleni, was a Muslim convert and she continued to rule and exert significant influence after Zar’a Ya’eqob’s death.

Servant or King? Constructing Balthazar

This study for Balthazar in Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\)) helped Peter Paul Rubens refine the figure of the king for a large painting of The Adoration of the Magi, commissioned by the town council of Antwerp, in Flanders, northern Belgium. The biblical story of three kings traveling from afar with gifts for the Christ child resonated in Catholic Antwerp, Rubens’s home city and a center of international commerce. The cult of the magi so captured the imagination of local inhabitants that many children were named Balthazar, Melchior, or Caspar after the kings. This oil sketch was painted on repurposed ledger paper; the marks of mercantile transactions are visible through the figure’s robe, face, and turban.

The immediacy and vibrancy of Rubens’s figure, with his parted mouth and gaze directed to the side, suggest an individual captured in a moment of speech and motion. Was this depiction inspired by an actual person, and if so, whom?

Rubens often drew from life (a practice used by other artists, including Andrea Mantegna, whose Adoration of the Magi was featured in the exhibition together with the oil study). One of Rubens’s patrons in Antwerp had Black African servants in his household, and Rubens made other studies using them as models. The Flemish city of Antwerp was a major center for the slave trade. Much research remains to be done on the status of forcibly Christianized Black Africans living there, specifically their positions and rights within domestic settings.

We also know that Rubens used an earlier print of Mulay Ahmad, the Hafsid Muslim ruler of Tunis, as inspiration for other works, such as The Three Magi Reunited (see Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\)). The Tunisian turban in Rubens’s head study casts the biblical character of Balthazar as a sixteenth-century North African king.

Thus Rubens’s Balthazar may be an amalgam of an unidentified sitter, likely a servant or enslaved person, and a nearly contemporary ruler. The artist’s image speaks to the intersections of power, faith, and race in commercial Antwerp at the height of its global reach.

African Europeans in the Courts of Europe

Europeans came to know African people in many different ways. While rulers made their way into the imagination of European artists, Africans living in Europe also became part of the art being produced at the time.

A significant number of Africans or members of the African diaspora in Europe occupied positions in the courts or noble households. Little documented, their histories can be guessed at from the evidence in archival documents and in art. Portrait of an African Man was long speculated to have been a painting of Christophle le More, a Black man, formerly a slave and groom, who went on to become an archer for the bodyguard of Emperor Charles V (see Figure \(\PageIndex{26}\)).

This painting by Jan Jansz Mostaert has long been celebrated as the only surviving European portrait of a Black man during this early period. Unlike images of Balthazar or other biblical figures, he wears the attire of a Flemish courtier. Moreover, he does not appear as a member of an entourage, but in the context of an individualized portrait. Who was this man?

Unlike the institution of slavery that became codified in the Americas at the time, it was possible for enslaved people in Europe to gain their freedom and to possess social mobility, working in positions as disparate as the elite bodyguard of the Holy Roman Emperor or as gondoliers in Venice.

Recent research has discouraged the identification of this sitter with Christophle, which leaves us only with the frustrating hints provided by his costume, such as the pilgrimage badge in his cap (to Our Lady of Halle, near Brussels), his gloves appropriate for a court setting, or for the embroidered bag at his waist, perhaps a gift from a wealthy patron.

Although his identity is unknown, he nevertheless offers a potent reminder of the lived experiences of Africans in medieval and Renaissance Europe.

This essay first appeared in the iris (CC BY 4.0)

This wooden sculpture in Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\) depicts one of the Magi [singular: Magus], or three kings who are said to have traveled from afar to visit the baby Jesus after his birth. Featured prominently in paintings and sculptures in the Middle Ages, such nativity scenes usually depict the three kings carrying gifts, and include one Black king, said to be from Africa and sometimes called Balthazar. This specific sculpture is from Swabia, a historic region of southwestern Germany.

As the preceding article notes, Europeans' ideas about Africa were shaped more by their own imaginings than actual interactions with people from the African continent. A sculpture like this one, then, can be studied to learn what German artists in the Middle Ages might have been considering and imagining in creating this image of an African king.

The Met Museum points out that “Trade routes, diplomatic excursions, and increased contact between Europe and Africa in the medieval period led to more images of people of African descent in art, particularly in scenes of this subject. The Magus’ elegant pose and contemporary attire are reminiscent of a medieval royal courtier. For its original audience, this figure represented an imagined African ruler and a reverent, wise man from a distant world.” This sculptural representation of the Magus blends traditions and artistic styles, revealing more about this German artist and artistic styles in Swabia than anything of Africa. As discussed in previous chapters (in discussions about Orientalism, for instance), Europeans often held inaccurate conceptions of cultures and people outside of themselves, including Africans. These misconceptions, stereotypes, and imaginings often correlated to later prejudices which were reinforced visually, via art. In cases such as with this king, it is important for viewers to remember that the depiction with an elongated body, gestural stance, and distinctive clothing all reflect styles of the later Middle Ages in Germany.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Jacopo Gnisci, "Christian Ethiopian art," in Smarthistory, December 22, 2016 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Jacopo Gnisci, "An Ethiopian icon," in Smarthistory, August 27, 2019 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Kristen Collins and Dr. Bryan C. Keene, "Images of African Kingship, Real and Imagined," in Smarthistory, June 27, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)