15.3: Mamluk

- Page ID

- 108698

Arts of the Islamic world: The Mamluks

by Glenna Barlow (excerpted)

The name ‘Mamluk’, like many names, was given by later historians. The word itself means ‘owned’ in Arabic. It refers to the Turkic slaves who served as soldiers for the Ayyubid sultanate before revolting and rising to power. The Mamluks ruled over key lands in the Middle East, including Mecca and Medina. Their capital at Cairo became the artistic and economic center of the Islamic world at this time.

The period saw a great production of art and architecture, particularly those commissioned by the reigning sultans. Patronizing the arts and creating monumental structures was a way for leaders to display their wealth and make their power visible within the landscape of the city. The Mamluks constructed countless mosques, madrasas and mausolea that were lavishly furnished and decorated. Mamluk decorative objects, particularly glasswork as in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), became renowned throughout the Mediterranean. The empire benefitted from the trade of these goods economically and culturally, as Mamluk craftsmen began to incorporate elements gleaned from contact with other groups. The growing prevalence of trade with China and exposure to Chinese goods, for instance, led to the Mamluk production of blue and white ceramics, an imitation of porcelain typical of the Far East.

The Mamluk sultanate was generally prosperous, in part supported by pilgrims to Mecca and Medina as well as a flourishing textile market, but in 1517 the Mamluk sultanate was overtaken and absorbed into the growing Ottoman empire.

Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis)

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker.

This is the transcript of a conversation held at the Louvre Museum in Paris. Click here to watch the conversation.

Steven: We're in the magnificent new Islamic Art Galleries at the Louvre in Paris. We're looking at one of their treasures. It's an object that was used to baptize the children of the royal family of France for centuries but it wasn't originally a French object.

Beth: No, it actually comes from the area of Egypt and Syria and it dates to between 1320 and 1340.

Steven: It was created by Mamluk artisans. The Mamluks had been slave warriors and they had asserted their independence and had been able to rule in the countries that are today Egypt and Syria for several hundred years. During that period, they became known as extraordinary craftsmen. They were known especially for their textile work and for their metal work. This is a premier example.

Beth: Normally, vessels like this would have large bands of calligraphy. This one doesn't. This one is filled with figures and animals and decorative patterning.

Steven: The only part that is not completely covered are the bottom few inches of the walls of the inside of the basin. Even the floor of the basin is completely covered. Let's start there.

Beth: There is a very abstract pattern there of sea animals.

Steven: These are very complex interconnected designs similar to tile work.

Beth: The basin is brass. It's got areas of silver and gold and black paste. I see eels in silver at the bottom.

Steven: And then above that, we see first a continuous band of animals that parade around the inner wall and then a wide frieze of men on horseback interspersed by animals as well as medallions, figures that are clearly rulers, as well as coats of arms.

Beth: There are two rulers. They sit frontally. They both hold goblets. The figures in between seem to be hunting—but also scenes of battle. We see limbs and we see a decapitated head so there's violence here.

Steven: The largest frieze is on the exterior.

Beth: There we see four figures in roundels. Each on horseback, slightly different. Two of them are hunting.

Steven: Another one is drawing his bow. Then the last seems to be processing, perhaps holding a club.

Beth: There are figures on either side of the roundels, sometimes four, sometimes five, all in procession toward the royal figures.

Steven: These figures are doing all kinds of interesting things. I'm looking at one, for example, that seems to be holding a leopard by a leash. Another seems to raise a goblet in one hand, perhaps in celebration and holding a vessel in the other. The figures are so dense that it actually takes time to be able to untangle the complex interwoven forms.

Beth: On the very bottom band, there are small roundels that carry fleur-de-lis. The Fleur-de-lis is the symbol of the royal family of France. Interestingly, it was also associated with a Mamluk Sultan. Art historians think these may have been reworked when they came to France. There are other alterations that make us think that the person who commissioned this was not the person who it was ultimately delivered to.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=500&height=281)

Steven: As you mentioned before, generally we would expect to see Islamic inscriptions. That would have been very common but they're absent here. There's some speculation that this may have been made for somebody who was not a Muslim. Perhaps it was even made for export.

Beth: The iconography is very complicated and art historians have not untangled it yet.

Steven: Look how rich the imagery is just under the rim. I can see a unicorn, an elephant. I can see a leopard, a camel, an antelope.

Beth: All processing, all running, all jumping. There's such movement and energy not only in the decorative forms which move in and out but also in the figures.

Steven: There is a little bit of Arabic inscription, the signature of the artist. We can see that just under the rim. Beth: Actually, he signed it six times, so maybe he was especially proud of it. His name was ibn al-Zain and actually the Louvre has another work by this great Mamluk artist.

Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, Cairo

by Dr. Christian A. Hedrick

Described by a 15th-century observer as a building with “no equivalent in the whole world,”[1] the mosque-madrasa-funerary complex of the Mamluk Sultan Hasan in Cairo has been considered one of the greatest mosque complexes ever built since its construction in the 14th century. It includes a mosque, a madrasa (school), a mausoleum, and other buildings—all within the same space. A complex like this one was typically designed as one structure and sponsored by one patron. If the building has a tomb within, as this one does, it will also be referred to as a “funerary complex.” It stands today as one of the most imposing mosque complexes in Cairo. The complex is a quintessential Mamluk building type, especially in Cairo. It was the first building to combine a madrasa and congregational mosque together in the Islamic world, and it set a new standard in Mamluk Cairo.

The complex was built during a period of crisis between 1350 and 1380, when plagues, Nile floods, and famine all undermined political stability. This complex of buildings was a means for Sultan Hasan—a young and weak ruler—to express his power and piety. Although the complex was never completed and Sultan Hasan was not buried here, it is a famous examples of the many funerary complexes that the Mamluk sultans erected.

The site

The Sultan Hasan complex is one of the largest buildings in all of Cairo. It faces directly onto a large maydan (public square) formerly called Maydan Rumayla (commonly known today as Maydan Salah al-Din) that was of central importance to Mamluk ceremonial rituals because it occupied the space just below the citadel, royal residences and military barracks that were the real, as well as symbolic, source of power and authority in Cairo. The complex was also very close to the location of the hippodrome and the famous horse market (that no longer survive), which played a key role in Mamluk military pursuits because, above all else, they were the most effective cavalry warriors since the Mongols.

Plan and design

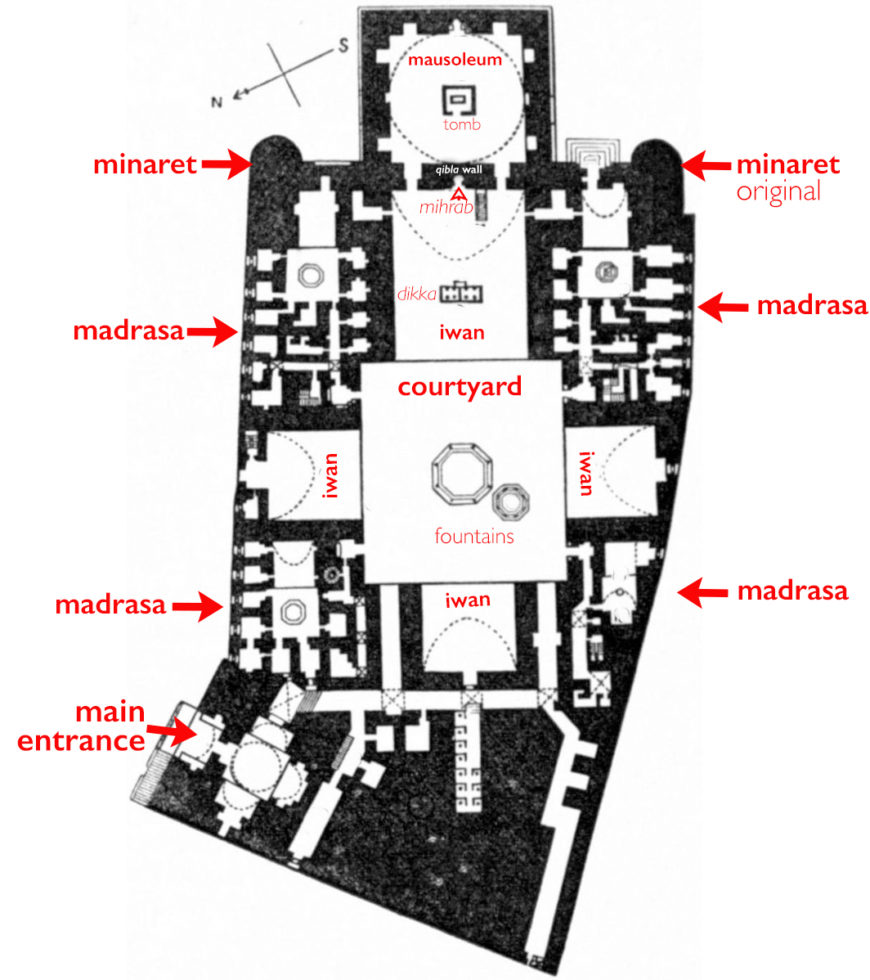

Although we do not have the name of someone considered an “architect” we do know the name of the “supervisor of construction,” an emir named Muhammad Ibn Baylik al-Muhsini, whose name is inscribed on a text band on the interior of the mosque. The complex is composed of a four-iwan jami‘ masjid (Friday Mosque), a madrasa (secondary school or college), and a qubba, or mausoleum (see Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). In this organization, the congregational mosque was composed of a central courtyard (sahn) with four iwans—halls enclosed on three sides and open to the courtyard on the fourth—on each side. When not in use for prayer, these spaces functioned as seminar meeting spaces for the madrasa.

The square space adjacent to the mosque is the mausoleum, and most of the rest of the building is dedicated to the madrasa and other support functions. The madrasa is also one of the largest in Cairo and contains four separate schools of Sunni Islamic law (each of which fits within the corner spaces around the central courtyard) faced by four unequal sized iwans, of which the southeastern was the largest because it is the direction of Mecca (known as the qibla iwan).

In the decades up to and after the sack of Baghdad in 1248, the Caliph’s power had diminished, so the Mamluk Sultan and various other strong men vied for power across the Islamic World. The fact that the building contained all four major Islamic schools of law underscored the strong relationship between the Mamluk Sultan and the Caliph, who had become a figurehead by this time.

The building’s waqf, or endowment document, has survived partially intact and tells us about the complex’s buildings and how they were used and staffed. The waqf explains that in addition to the mosque, madrasa, and mausoleum, the complex was also to contain spaces for physicians to service the community and a sabil-kuttab (public water fountain dispensary and primary school for boys). In all the waqf stipulated that there should be accommodations for over 500 (madrasa) students, 200 school boys, and 340 staff members in all making it the largest of its day. [2]

The decoration and design

The entrance portal and vestibule, and courtyard with iwans

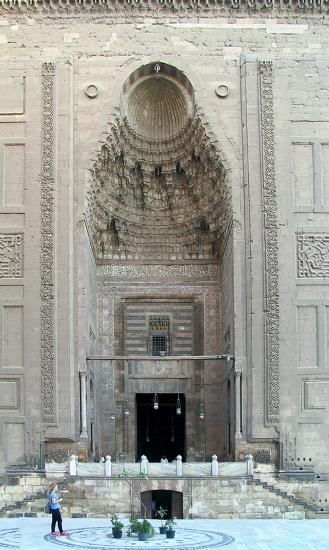

The exterior of the complex is stone, and the interior is mostly brick with stucco decoration. Due to the exterior’s vast surface, most decorative carving occurs near the entry portal and the elevation of the mausoleum facing onto the maydan (public square). One enters the complex through an enormous portal—the largest in Cairo—which is capped by an enormous hood filled with muqarnas (carved stalactite-shaped decoration).

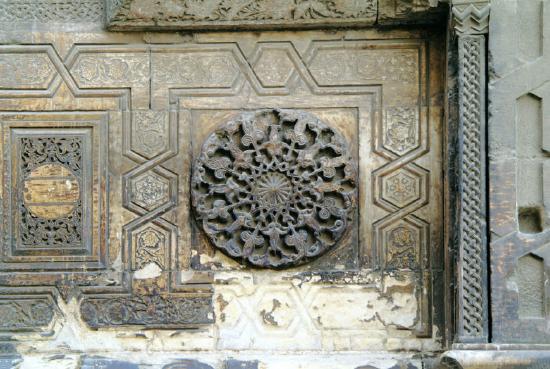

Both sides of the portal have highly refined stone carvings, including spiral cut columns to exaggerate their height, panels with interlacing geometric patterns, carved arabesques (intertwining and scrolling vines), and even Chinese decorative motifs (see Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)). Chinese designs were transmitted, alongside with Chinese goods, on the silk roads, especially after the peace treaty signed between the Mamluks and Mongols in 1322, and would later make their way into Ottoman ceramics too.

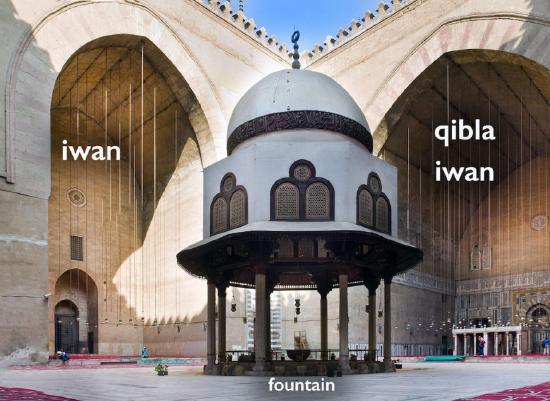

After passing through the entrance, you then enter a vestibule that allows you to either enter the mosque or other areas of the complex (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)). Entering the mosque, you are confronted with the vast and grand open paved courtyard with four large iwans facing onto it and a large domed ablution fountain in the center.

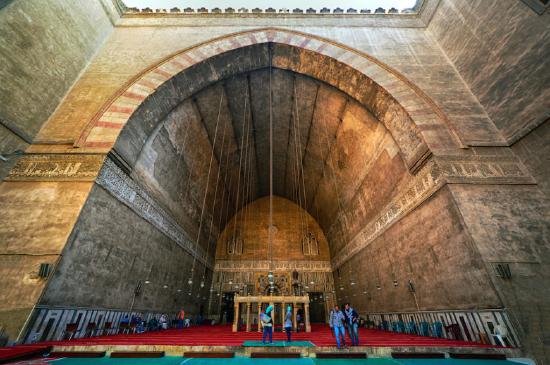

The main or qibla iwan

According to contemporary chroniclers, Sultan Hasan ordered the main iwan with the qibla (a wall indicating the direction of Mecca) to be “five cubits wider” than the greatest known arch in the world at the time: the famous Sasanian Taq-i Kisra in Ctesiphon from centuries earlier. (see Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)) While the arch was not, in fact, bigger, this detail reveals something about Sultan Hasan’s global ambitions.

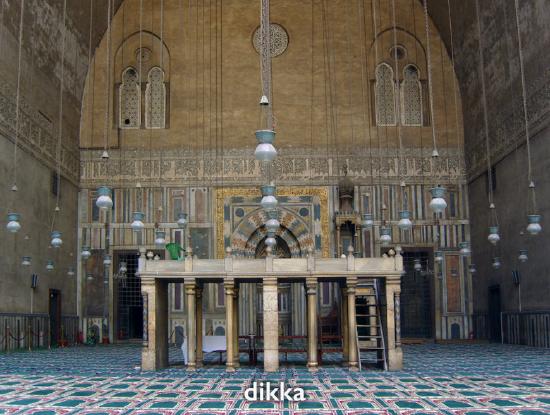

The main iwan is by far the most elaborately decorated due to its association with Mecca (see Figures \(\PageIndex{13}\) and \(\PageIndex{15}\)). The qibla wall within it is articulated with a rich marble paneled dado, and a large and unique stucco text band in Kufic letters above that wraps around the entire iwan.

The mihrab niche (also indicating the direction of Mecca) is given special treatment with a pointed arch, stone ablaq (alternating color stone), and is flanked by Gothic style colonettes, which were included due to exchanges with the Crusader kingdoms in and around Jerusalem. On either side are doors (one original bronze remains) that lead into the mausoleum directly behind the qibla wall. There is also a marble minbar (pulpit with steps) from which the sermon would be preached.

In front of the iwan, almost in the main courtyard area, stands the dikka—a large raised platform carved out of marble that allows individuals to loudly repeat the prayer so those in the back can hear it (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)). The iwans also had approximately 155 oil lamps hung from their ceilings at the same height above the ground, which, at night, would have illuminated the mosque in a magical way.

The mausoleum

The mausoleum—Sultan Hasan’s intended eternal resting place—is immediately behind the qibla wall with the mihrab, which represents a significant shift in planning and symbolism; this organization did not happen prior to the Mamluks. Placing a mausoleum directly behind the qibla wall has the—likely intended—result of hundreds of people praying in the direction of the tomb (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)). If that were not enough, the waqf actually stipulates that there would be 160 full-time hafiz (men who were tasked with reciting the Qur’an out loud) placed in the various deep window sills around the mausoleum reciting the Qur’an at all hours of the day such that passers-by are reminded of the sacred gifts the sultan bestowed on the city in the form of this religious complex.

Famed minarets

On the exterior, an unprecedented four minarets were ordered for the complex including two flanking the portal and two flanking the dome on the outer corners of the mausoleum on the maydan, or public square (see Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)). Out of the four giant minarets, only three were constructed and two of those collapsed; the first while Sultan Hasan was still alive in 1361 killing roughly three hundred people, mostly children attending the kuttab (primary school). The collapse was seen as a bad omen and the sultan was murdered a month later. Another minaret collapsed in 1671 while the mosque was full of worshipers, but luckily it fell away from the crowd. The only original remaining minaret is on the south-east corner of the mausoleum and reaches a staggering height of approximately 84 meters above street level.

The minarets of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan are famous for initiating the famous three-tiered minarets—a signature of Mamluk religious architecture—for which the city of Cairo is famous. In the Sultan Hassan mosque, the first several stories of the surviving minaret are integrated into the wall of the complex. Above that the minaret’s base is square until, further up it transitions into an octagon with small balconies on every other face. A larger balcony with muqarnas separates the middle tier, which is also octagonal, but significantly truncated and without decoration. The top balcony is articulated with muqarnas, upon which an open colonnade pavilion is capped with another ring of muqarnas that transitions to a tapered stone bulb. This example was to be emulated and refined throughout the rest of the Mamluk period, forever defining Cairo’s iconic skyline.

World famous mosque

Although Sultan Hassan was murdered by one of his own Mamluks, construction of the mosque continued after the Sultan’s death, but was never completed. His body was never recovered nor entombed in this mosque. During his short reign, he managed to restore the mosque of al-Hakim in Cairo and monuments in Mecca, establish a madrasa in Jerusalem, build a lavish palace in the citadel in Cairo, construct a mausoleum for his wife and one for his mother, build several sabil-kuttabs (school and water dispensary), and founded one of the most famous mosques in the world. Clearly, architecture was a way he could express his ambitions. The building remains one of the most ingeniously designed mosques in the history of Islamic architecture; no other Mamluk monument displays as many innovations as this single building.

Notes:

- Khalil al Zahiri (born c. 1410): “Elle n’a pas de pareille au monde,” quoted from Max Herz, La mosquée du sultan Hassan au Caire (Cairo, 1899)

- The sail-kuttab (fountain and school for boys) was built, but it was destroyed when the minaret fell on it in 1361 killing many of the children. The accommodations for the physicians (and 10 medical students) was stipulated in the waqf and its location was specified as occupying an upper floor behind the entry way—but this area is now ruined and we do not know for certain whether it was built and destroyed, or never built at all.

Articles in this section:

- Glenna Barlow, "Arts of the Islamic world: The medieval period," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Mohammed ibn al-Zain, Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis)," in Smarthistory, December 15, 2015 [transcript] (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Christian A. Hedrick , "Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, Cairo," in Smarthistory, November 18, 2021 (CC BY-NC-SA)